Chapter 5

Patronage and the Social and Cultural Status of the Artist

Introduction

This chapter introduces you to two important and inter-related themes:

- patronage

- the social and cultural status of the artist.

Patronage and the status of the artist have evolved a great deal over the centuries, and this extended Introduction provides a brief overview of the history of both themes and considers how the form and motives of patronage have changed in accordance with the wider social and economic contexts. Throughout this chapter, we will address the ways in which artistic patronage and its motivation have influenced both the appearance and our interpretation of art and architecture.

A brief history of patronage

Patronage is the commissioning or purchasing of works of art by an individual, group or state. There are many different possible motives for becoming a patron. These include:

- – private patronage for pleasure, commemoration, investment, prestige

- – group patronage for power and corporate identity, commemoration, assertion of status, competitiveness, devotion, civic pride, nationalism

- – church patronage for the glory of God, private devotion, didacticism (a focus on the instructional qualities of works), power and the status of the church as a political force

- – monarchy and state patronage for reasons of connoisseurship, national status, dynasty-building, commemoration, propaganda.

The history of patronage runs in parallel with the history of ascendant monarchs, religions, merchant classes and the artist as individual, even celebrity. Needless to say, the role and nature of patronage has changed over the centuries. During the period known as Classical Antiquity the state was the chief patron of the arts; in the medieval period patronage was dominated by the church, the papacy and powerful individuals. It was during the Renaissance that a new form of patronage emerged: lay patrons increasingly exerted their influence over artistic production, and donor portraits were common.

During and after the Renaissance, the middle classes began to emerge across Europe, alongside a rise in merchant and banking families. In Florence, guilds competed to commission the greatest artists, as did confraternities of lay people. During the High Renaissance, patrons came to recognise the artist as an intellectual and even a genius.

During the seventeenth century the church was the dominant patron of the arts, which it invariably employed for propaganda to fuel the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Royal court painters flourished, as did private patronage and collections were amassed, such as that of Charles I in England.

In the eighteenth century a new commercial patronage emerged with the expansion of trade and the opening up of the New World. Academies were founded all over Europe, and ready-painted works – not commissioned by patrons but made to sell to whoever might like them – were sold by artists themselves or via the middlemen of the expanding art market: the dealers.

The nineteenth century saw the resurgence of more traditional patronage from the church, the state and the monarchy, although the trend for works made to sell to any willing buyer also continued. New industrialists bought art to demonstrate their nouveau riche prestige. This was the century in which the dealer emerged as someone who could broker a mutually beneficial relationship between individual artists and rich would-be collectors.

The twentieth century saw the role of the dealer increase and the artist-dealer relationship flourish. While the role of the critic was felt in the nineteenth century – for example, Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti vowed never to exhibit in public again, following a bad review of The Annunciation (1849–1850) – twentieth-century critics, perhaps as a consequence of the power of the media, became increasingly significant and could make or break an artist’s reputation. Collectors turned into supercollectors and artists found the technical means to promote their ready-painted work without the need for a patron, dealer or even a physical exhibition space.

The changing status of the artist

The social and cultural status of the artist relates to the rank or position of artists in society in relation to others, and so reflects the importance accorded to art in a given society. How important is art considered to be? Is it considered a reflection of a society’s highest values or merely useful decoration? You also need to consider the individual success or otherwise of particular artists. Did they achieve fame and riches in their lifetime, or did celebrity and adulation only occur posthumously? The social and cultural status of an artist or architect is often inextricably linked to the quality and quantity of patronage they enjoyed, and both themes are examined jointly, when appropriate, in this chapter.

The factors to be considered when assessing the status of art and artists in general in society are:

- – Autonomy: how much freedom does an artist have at any particular historical period over the choice of subject matter and style? Conversely, how much influence do patrons – or the market – wield over artists?

- – Education or training: do artists have special institutions dedicated to their training? Are artists members of guilds or academies or other professional associations? Have they trained with others of artistic status?

- – Economic rewards: how well rewarded are artists monetarily? Has the economic value of an artist’s work increased since his or her death?

- – Social marks of status: what indicators of social status do successful artists in a particular society receive? Do they receive knighthoods or other honours? Do they socialise with the richest in society or the poorest? Are they expected to act as critics of society or to support it?

- – Institutional prominence: how far do works of art, and therefore artists, benefit from being exhibited in gallery or museum collections? How influential are art critics? How much money is made by selling works of art at auctions and by dealers?

The factors to consider when assessing any individual artist’s degree of personal success include:

- – Critical renown: what do art critics and art historians say about the artist? How much is published about the artist and his or her work? Is their work taught in schools and universities, and if so is it considered to be part of the art-historical ‘canon’?

- – Financial rewards: has the artist achieved wealth through his or her work?

- – Popular reputation: has the artist become well-known to a general, non-specialist audience? What degree of promotion does the artist receive through publicity, self-publicity (self-portraits, autobiography), marketing, discussion by critics, art historians, press, curators, patrons?

The ancient Greeks, and later the Romans, differentiated between the liberal arts for educated classes and the mechanical arts for tradesmen. During these times, artists – as we know them today – were treated like labourers and worked for daily rates; although some were valued and financially successful, most were still of a relatively low social status.

In the medieval period, most art was made for the glory of God and the individual artist was not celebrated. Artists worked with their hands and, on the whole, were seen as no better than skilled labourers. A painting was more valued for its use of expensive materials than for the artist’s creativity and skill.

It was only during the Italian Renaissance that a change in the status of the artist took place, fuelled both by the emerging philosophy of humanism and by larger economic changes and the rise of a merchant class. Secular patronage and the emergence of wealthy merchant-patrons changed demand, and the artist became a creative ally to the patron. For the first time, artistic skill was believed to be God-given and the artist’s fame was promoted in treatises and biographies, such as Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (1550).

In the seventeenth century, artists and architects in Italy, for example, enjoyed a high status as they helped the Catholic Church to rebuild Rome; conversely, the fame of some artists increased the prestige of their patron. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries European nation-states placed increasing importance on art collections and, accordingly, on museums as treasure-houses and display vehicles of a nation’s wealth and prestige. The rise of national institutions and museums – such as the Royal Academy (founded 1768) and the National Gallery (founded 1824) in England, and the Louvre (founded 1793) in France – helped to bring about the rise to international fame of individual artists, as well-heeled European travellers visited the collections of courts, popes and noblemen, and returned from the Grand Tour determined to purchase works by some of the artists they had seen.

The nineteenth century saw artists creating and selling works independently and it is therefore at this point that the figure of the struggling artist emerges. Many artists depicted their poverty and challenged, rather than accepted, the political status quo. Artistic rules and genres were likewise broken and dissolved and, in the process, individual artists came to prominence as the latest scandalous sensation, or leader of a new artistic tendency or school. Arguably, art lovers, patrons and publics in the nineteenth century increasingly cared less for the richness of an artwork’s materials than for the reputation of the artist who had made the work.

The twentieth century saw this trend intensify, with avant-garde artists disregarding traditional mediums and adopting such forms as the readymade, an everyday object selected by the artist and displayed as art with little or no modification. Such a development appeared to confirm that the rules of art had all but disintegrated. Anything could become art, or so it seemed, if a famous artist said it was art. The artist as celebrity emerged with gusto, fuelled by the media-saturated times. At the same time, however, this era has seen the museum become even more important, as it is arguably institutional acceptance that now marks a work as ‘art’. Having charted a brief history of the changing status of the artist, let us now examine more closely each phase in this story, using individual artistic examples.

Private Patronage in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

Figure 5.1 | Sandro Botticelli, The Adoration of the Magi, c.1475, tempera on wood, 111 × 134 cm, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Source: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Library / G. Nimatallah.

Glorification of the patron and self-glorification by the artist

In the Renaissance, the Italian city of Florence was a self-governed, independent state. From around 1434, however, the Medici banking family unofficially ruled the city. The dynasty that they formed commissioned a vast array of paintings, sculptures and architecture, and their generosity and competitive nature ensured the city’s status as the artistic centre of Europe during the fifteenth century and beyond. Florentine Renaissance artist Benozzo Gozzoli (1421–1497) was commissioned by the Medici family to make a fresco for the private chapel of the Palazzo Medici. As was common practice, it included a representation of his patrons in The Procession of the Magi, c.1459–1461. But as an indication of the relatively high status of the artist, Gozzoli also included a self-portrait with the words opus benotti (work of Benozzo).

The Medici family was so powerful that its members even appeared in paintings they had not directly commissioned. Guasparre di Zanobi Del Lama commissioned The Adoration of the Magi, c.1475, from Sandro Botticelli (originally Alessandro Filipepi, 1445–1510), which features several members of the Medici family. Why did Guasparre pay Botticelli to depict so many members of the most powerful banking family in Florence? The answer may lie in Guasparre’s dubious past. The lowly patron had been convicted of embezzlement in 1447 but made his subsequent fortune as a broker and money changer. This wealth allowed him to commission Botticelli to paint this altarpiece in a chapel of Santa Maria Novella. Bearing in mind that the Medici were enrolled with the Guild of Money Changers (Arte di Cambio) it is little wonder Guasparre wanted to secure a favourable association with them. The Adoration was the only artistic product of Guasparre’s brief social elevation. In 1476 he was convicted of fraud again and banned from trading (Deimling, Botticelli, p. 22).

As well as including the portrait of his patron Guasparre, the grey-haired merchant in a light blue robe on the right-hand side, and portraits of the Medici, Sandro Botticelli also unashamedly seized the opportunity to paint his own portrait among the group. The artist (far right, in a yellow robe) positioned himself as compositional counterpart to no less a figure than the Florentine ruler Lorenzo de’ Medici, who was known as ‘the Magnificent’ (far left, wearing white stockings). Both have rather self-satisfied expressions, and together they frame the painting.

Despite ostensibly being a religious painting, the Holy Family is accorded less importance than a whole series of contemporary portraits. This painting was commissioned for personal gain, self-promotion and to gain favour; forget the Magi, it is the Medici – the de facto rulers of Florence – who are the most important potential givers of gifts in this scene. They include Cosimo the Elder, founder of the Medici dynasty, who is kneeling directly before the Virgin and Christ Child, and his son Pietro (Lorenzo’s father), centre stage in vibrant red. They appear crownless, a deliberate omission given the family’s need to present a humble image in a city that was, after all, a republic. There is some dispute over the identity of some of the people in the painting. Use your online research to find out more about Medici dynasty and which of them might be shown here.

Figure 5.2 | Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, portrait of Giovanni (?) Arnolfini and his wife Giovanna Cenami (?), 1434, detail of chandelier and van Eyck’s signature on back wall, oil on oak panel, 82.2 × 60 cm, London, National Gallery.

Source: National Gallery, London, UK /Bridgeman Images.

There are countless other examples of Renaissance painters appearing in cameo roles in their own paintings. Jan van Eyck (1395–1441) unapologetically included ‘Jan van Eyck was here, 1434’ on the central vertical axis of his Arnolfini Portrait, 1434 (examined in Chapter 1, as an example of double-portraiture, and in Chapter 2, as an example of oil painting). In relation to the portrait’s patron, Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini (an often contested identity) the commission was a status symbol not only in its schematic depiction of wealth and success but also as evidence of the material ability of the client to commission such a well-regarded artist.

The meaning of this painting is that wealth – the wealth to hire Van Eyck – can purchase immortality, even if no one can be quite sure what your name was.

(Journalist Jonathan Jones quoted in Graham-Dixon, Art: The Definitive Guide, p. 144)

Jan van Eyck enjoyed the constant patronage of Philip the Good (Duke of Burgundy), and records show that the artist was highly valued and handsomely paid as a court painter to the Duke. Indeed, since Van Eyck was in receipt of an annual salary from the court when he painted the private double portrait of the Arnolfinis, it seems highly likely that ducal permission was sought and granted. This fact heightens the status of the Arnolfinis and validates the size and prominence of the artist’s signature – everybody’s cachet is enhanced by the deal. Unlike many of the artists featured in this chapter, much of Jan van Eyck’s biographical detail remains unknown, even though he did have a biographer – Karel van Mander – itself a sign of status. In fact, Van Mander, who wrote The Painter’s Book, 1604, falsely attributed the invention of oil to Van Eyck (as had Italian Renaissance biographer Vasari in the previous century). In truth, the artist’s technical innovation was the perfection of oil painting, and not its invention.

The famously androgynous bronze David, 1420–1440 (examined briefly in Chapter 3) was commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici from Renaissance sculptor Donatello (originally Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, c.1386–1466). According to the story from the Old Testament, David is the young shepherd boy who, against all odds, defeats the giant Goliath with a single stone to the head. He then beheads Goliath in a final act of triumph. For the Florentines, this story was of great importance as it reflected their own political position as a small state, which would nevertheless triumph against adversity.

However, Donatello’s rendering of the subject was radical and new in a variety of ways: the figure’s nakedness – heightened by his flamboyant hat and boots – set him apart from other fifteenth-century depictions of the same subject. The hat itself was a deviation from the usual iconography of the young shepherd boy, and the way the toes on David’s left foot caress Goliath’s heavy beard lend a sensuality that also broke with the past. Cosimo de’ Medici’s acceptance of this break with tradition reveals the family’s liberal attitude towards the arts. The Medici wanted to be known as intellectual leaders and despite the religious subject matter, this commission was certainly evidence that their interest in humanism and Neo-Platonism meant more to them than the furore this particular David caused.

Figure 5.3 | Donatello, David, 1440 (before restoration), bronze, height 158 cm, Florence, Bargello Museum.

Source: © 2015. Photo Scala, Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali.

Furthermore, as the first free-standing nude bronze since Antiquity, David was capable of being seen as an emblematic new man – a naked and individual figure, breaking completely with medieval tradition. Its placement, too, is revealing. This particular symbolic defender of the city was tucked away in the private courtyard of the Medici palace – perhaps because it was considered too shocking to be shown in public, or perhaps because this placement would allow it to serve as a symbolic gesture for its patron. In appropriating David – who represented the Florentine Republic – the Medici expressed a quiet ambition, but only in the safety of their own home.

The status of the artist had increased exponentially since the medieval period, and the success of Vasari’s Lives of the Artists was testament to public interest in the individual characters and achievements of artists. For example, Vasari describes the day when the grouchy Donatello pushed his own bronze handiwork over a parapet wall onto the street below, and, rather than punishing him, Cosimo de’ Medici declared [o]ne must treat these people of extraordinary genius as if they were celestial spirits, not as if they are beasts of burden (Vasari, Lives of the Artists, p. 107).

The Medici, self-made financiers and well-read connoisseurs, respected artists as individuals and recognised the artist’s ability to propagate the dynasty’s power all over Florence and beyond. As such, they were typical of powerful citizens from wealthy banking and merchant families who during this period commissioned art and architecture on an unprecedented scale. Many of these citizens were self-made and, arguably, valued those artists who matched their ambition. One notable example in the north of Europe was the painter Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who seemed to aspire to Florentine panache and whose Self-Portrait, 1500, is an extraordinary image of artistic self-righteousness.

Dürer’s Self-Portrait demonstrates the changing status of the artist during Private Patronage in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries Patronage and the Social and Cultural Status of the Artist the Renaissance and the emerging importance of the artist as a gifted individual. In the painting, Dürer shamelessly presents himself in the guise of Christ, perpetuating a self-image and status in the north of Europe somewhat akin to that which Vasari was perpetuating in the south for the artists he wrote about in his Lives of the Artists. Dürer’s monogram hints at the persona he was actively creating for himself, and the skilful depiction of his fur collar would not have been lost on his audience either. Its black background establishes a certain gravitas – he is an intellectual artist. This famous image is probably one of the earliest examples of the artist as ‘celebrity’ in Western art.

Figure 5.4 | Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, 1500, on limewood, 67 × 49 cm, Munich, Alte Pinakothek.

Source: akg-images.

Public Patronage in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

The importance of guilds and the rise of the ‘artist-genius’

Much of Florence’s wealth depended on the manufacture and trading of wool and cloth and, of course, the commercial success of banking. Florentine guilds were secular corporations that controlled the arts and trade; collectively, they influenced the artistic legacy of Florence. During the Renaissance in Florence there were seven major guilds (collectively known as the arti maggiori), five middle guilds (arti mediane) and nine minor guilds (arti minori) which competed with each other to gain commissions and status. The rivalry between guilds extended to the status of the artists they employed. A notable example is the competition set up by the Cloth Importers’ Guild (Calimala) – one of the wealthiest guilds in Florence – in 1401 for the commission to decorate the bronze North Doors of the Baptistery. The competition was won by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), with Filipo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) as runner-up. Another major guild was the Wool Merchant’s Guild (Arte della Lana). It took charge of commissioning a dome for the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence Cathedral) in 1418. This time, Brunelleschi beat Ghiberti to the prize.

Figure 5.5 | Filippo Brunelleschi, Dome of Florence Cathedral, 1420–1436.

Source: © santof / iStockphoto.

Brunelleschi’s dome may be examined in relation to a number of themes in this book. Already scrutinised for the materials, techniques and processes related to its construction in Chapter 2, the dome’s monumental scale (testament to the domination of religion during the fifteenth century and the competition between neighbouring Italian cities, particularly Pisa and Siena) reveals a great deal about its social and historical context. In the context of this chapter, its very existence not only demonstrates the importance of commercial patrons such as the Wool Guild, but also reveals the tremendous status some Renaissance artists enjoyed in their own lifetimes.

Brunelleschi’s body lies in the crypt of Florence Cathedral, a great honour for a great Renaissance man and a mark of the changing status of the artist in this period. Thousands of mourners paid their respect at his funeral held in Santa Maria del Fiore (the actual name of Florence Cathedral) itself, and on his marble slab is the inscription CORPUS MAGNI INGENII VIRI PHILIPPI BRUNELLESCHI FIORENTINI (Here lies the body of the great ingenious man Filippo Brunelleschi of Florence) (King, Brunelleschi’s Dome: The Story of the Great Cathedral in Florence, p. 156).

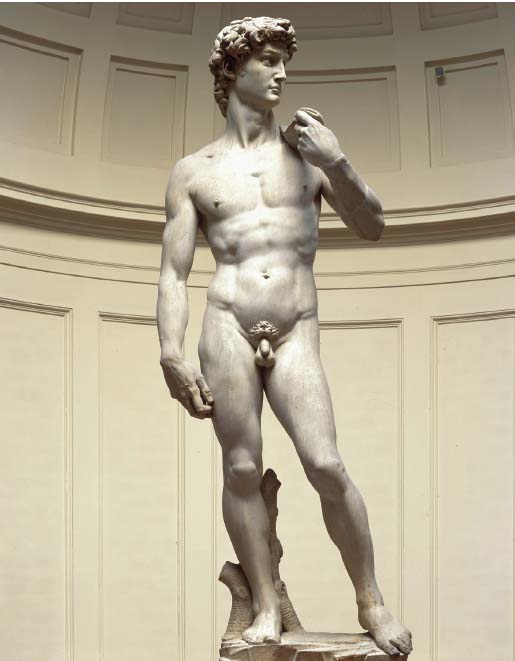

Brunelleschi’s dome for Florence Cathedral was not only a symbol of civic pride, but a symbol of the Renaissance itself. Similarly, High Renaissance giant Michelangelo (originally Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, 1475–1564) created a world-famous emblem of the city with his iconic sculpture David, 1501 a few decades later. Michelangelo’s stone subject was the same Old Testament figure that Donatello had forged in bronze for the Medici around 60 years earlier, although the comparison ends there.

Michelangelo was awarded the commission for the colossal figure of David by the Arte della Lana (Guild of Wool Merchants), which was also responsible for the decoration and maintenance of the cathedral. As this example shows, patronage is sometimes difficult to classify: Michelangelo’s David was commissioned by a Florentine guild – making the commission a work of corporate patronage – but the statue itself was intended for the cathedral, which means the commission exemplifies both religious and civic patronage. By this time, Michelangelo’s status as a sculptor had already been established by works such as his serene Piètà, examined in Chapter 1 as an example of a religious subject. However, with David, he was widely held to have surpassed the skill and beauty achieved by the sculptors of Classical Antiquity.

Michelangelo achieved these supreme artistic results despite being given a second-hand block of marble from which to create his masterpiece. (Agostino di Duccio had tried and failed with the same block four decades earlier.) The following is an extract from the contract for Michelangelo’s David, dated 16 August 1501: Spectabiles … viri, the Consuls of the Arte della Lana and the Lords Overseers [of the Cathedral]18 being met Overseers, have chosen as sculptor to the said Cathedral the worthy master, Michelangelo, the son of Lodovico Buonarroti, a citizen of Florence, to the end that he may make, finish and bring to perfection the male figure known as the Giant, nine braccia in height, already blocked out in marble by Maestro Agostino19 grande, of Florence, and badly blocked; and now stored in the workshops of the Cathedral.

And without doubt this figure has put in the shade every other statue, ancient or modern, Greek or Roman.

(Vasari, Lives of the Artists, p. 339)

The work shall be completed within the period and term of two years next ensuing, beginning from the first day of September next ensuing, with a salary and payment together in joint assembly within the hall of the said of six broad florins of gold in gold for every month. And for all other works that shall be required about the said building (edificium) the said Overseers bind themselves to supply and provide both men and scaffolding from their office and all else that may be necessary. When the said work and the said male figure of marble shall be finished, then the Consuls and Overseers who shall at that time be in authority shall judge whether it merits a higher reward, being guided therein by the dictates of their own consciences. (Holt, A Documentary History of Art, pp. 4–5)

Figure 5.6 | Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504, marble, height 434 cm, Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia.

Source: akg-images / Andrea Jemolo.

The timescale within which Michelangelo had to work – and for which he would be supplied with the necessary practical and financial support – was clearly specified, as were the limitations imposed by the poorly blocked out piece of marble he was commissioned to carve. There was thus no margin for error – or space for significant contrapposto in the figure. Nevertheless, Michelangelo achieved a forceful and warrior-like effect through a subtle distribution of weight in the figure and a determined expression. Blood seems to pump visibly down his arms into his oversized hands, reinforcing his virility and readiness for battle.

Michelangelo’s status during the Renaissance was unsurpassed. We learn from Condivi’s authorised Life of Michelangelo, 1553, that the Pope treated the artist like a ‘brother’ and Vasari positively swooned over the artist’s apparently divinely inspired creations, describing him as a ‘Tuscan genius’. Vasari also recalls how Michelangelo was invited into the Medici household to live and how Lorenzo the Magnificent wanted to keep him as one of his own sons (Vasari, Lives of the Artists, p. 331).

Michelangelo’s status may be measured by the fact that his death was marked by an elaborate funerary procession. The Florentine Academy of Painters and Sculptors stated their wish to pay tribute to the greatest artist of their profession that has perhaps ever lived.

Despite his unprecedented status and well-tolerated bad temper, in a letter to his biographer, Vasari, he wrote Messer Giorgio, Dear Friend, – God is my witness how much against my will it was that Pope Paul forced me into this work on St. Peter’s in Rome ten years ago (Holt, A Documentary History of Art, p. 19). He was referring to the Last Judgement wall fresco which, against his passion and his wishes, he painted in the Sistine Chapel for his authoritative patron Pope Paul III. (He had painted the ceiling three decades earlier for Pope Julius II.)

Michelangelo may have angered popes but he also charmed them – not least because they regarded his artistic skill as invaluable in securing their long-lasting reputations. Of Pope Paul III, Vasari said, God ensured future renown for his holiness and for Michelangelo. How greatly are the merits of the Pope enhanced by the genius of the artist? (Vasari, Lives of the Artists, p. 337).

Considering that an artist has enjoyed such powerful patronage, and such long-lasting fame, does the fame of the artist still affect our interpretation of his work? Should it? It is easy to conflate the value of a work with the artist’s status, especially in the case of Michelangelo. His works have become famous the world over. He has become a transnational brand.

Papal and Church Patronage in the Seventeenth Century

Figure 5.7 | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Ávila, 1645–1652, marble, life-size, Rome, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Cornaro Chapel. Source: © Adam Eastland Art +Architecture / Alamy.

The glory of God?

By the seventeenth century Florence had lost its artistic dominance, and Rome became the major cultural centre of Italy. Rome’s supremacy during this period is partly attributable to powerful and visionary papal patrons but also to their relationships with the artistic masters of their time. The High Baroque masters of the mid-seventeenth century, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669) and Francesco Borromini (1599–1667), enjoyed constant papal patronage. When Urban VIII became Pope in 1623 he was alleged to have said to the young and precociously gifted Bernini: It is your great good luck, Cavaliere … to see Matteo Barberini Pope; but we are even luckier in that the Cavaliere Bernini lives at the time of Our pontificate (Wittkower, Art and Architecture in Italy 1600–1750, p. 2).

With the help of their favourite artists, the Baroque popes – Urban VIII Barberini (ruled 1623–1644), Innocent X Pamphili (ruled 1644–1655) and Alexander VII Chigi (ruled 1655–1667) – set about rebuilding Rome’s magnificence during the Catholic Counter-Reformation. (See Chapter 4 for more details on the social and historical context of the seventeenth century.) St. Peter’s in Rome, the heart of Christendom on earth, was their main focus, but a multitude of smaller projects, nearly as majestic, gained significant fame for their creators. The favoured prodigy of popes, Bernini was all too aware of his talents and the high status they afforded him. As historian Simon Schama points out, [f]alse modesty was definitely not one of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s failings. But since there had never been a time when he has not been hailed as a human marvel, it’s surprising he wasn’t more swollen-headed (Schama, The Power of Art, p. 82).

However, under the pontificate of Innocent X, the golden boy of Urban’s empire predictably fell out of favour. A new Pope was always keen to make his Papal and Church Patronage in the Seventeenth Century Patronage and the Social and Cultural Status of the Artist own competitive mark on the city and, in addition, Bernini’s devout life had suffered a sinful episode: he’d hired a servant to slash his mistress’ face upon the discovery that she’d also been sleeping with the artist’s brother. It was at this point, suffering a dip in both patronage and pride, that Bernini was given one of the most memorable commissions of his entire career. Cardinal Federico Cornaro became patron to one of Bernini’s most important works when he commissioned him to create a private family chapel in the left transept of the church of S. Maria Vittoria in Rome. Cornaro paid 12,000 scudi, a very sizeable sum indeed, for his spectacular aedicule and, in so doing, allowed Bernini to create a masterpiece of both self-promotion and piety – probably in that order.

St. Teresa is modelled here as the patron’s intercessor between heaven and earth, and even to modern eyes Bernini’s illusionism is spectacularly effective. Bernini has incorporated the patron’s family into the side walls in the same way that some painters incorporated their donors into altar paintings. Cardinal Cornaro is joined by deceased members of the Cornaro family to watch the mystery of their faith unfold. Set high in their theatre-style boxes, they discuss the event – a composition, one would assume, that was inspired by Bernini’s set-designing past. The chapel’s patron is distinguished from his deceased companions by his glance beyond the mystical sphere towards ours, which is earthly; and in so doing helps to draw us into the scene. Whatever its spiritual success, this altarpiece certainly helped to redeem Bernini’s tainted social status and still serves to showcase his genius today; it remains a monument that innovatively fuses painting, sculpture and architecture.

Art historian William Barcham has suggested that Cardinal Cornaro commissioned the Ecstasy of St. Teresa because he aspired to climb the papal hierarchy himself – he was the son of a Venetian Doge after all. The entrepreneurial Cardinal must have known that his choice of high-profile sculptor and dramatic multi-figure composition would keep him in the public eye (Harris, Seventeenth-Century Art and Architecture, p. 108).

Cardinal Cornaro fulfilled his personal need to make manifest his success and pro-vide himself with a marble bridge to his place in heaven, but he also afforded Bernini artistic freedom to create a scene from St. Teresa’s life as he, the artist, imagined it.

Figure 5.8 | Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Cornaro family sculpted into lateral walls of The Ecstasy of St. Teresa of Ávila, 1645–1652.

Source: © Stefano Ravera / Alamy.

Not all artists were allowed the same degree of freedom by their patrons. One notable example of the control that could be exerted by patrons is provided by the wooden sculpture Christ of Clemency, 1603, made in the neighbouring country of Spain by Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649).

Christ of Clemency was commissioned for the private chapel of Mateo Vázquez de Leca (archdeacon of Carmona). Despite his presumed religiosity, Vázquez de Leca had consorted with prostitutes; supposedly, one memorable night, however, he was pursuing a woman who turned around to appear as a ghostly skeleton. This vision halted Vázquez de Leca’s ungodly behaviour and prompted him to commission the aptly named Christ of Clemency. The patron saw to it that the representation of Christ was manipulated sufficiently to grant him the forgiveness he so desperately sought. Accordingly, the patron afforded very little artistic licence to Montañés; the contract stressed that Christ was to be alive, before He had died with the head inclined towards the right side, looking to any person who might be praying at the foot of the crucifix, as if Christ Himself were speaking to him (Bray et al., The Sacred Made Real, p. 25).

Figure 5.9 | Juan Martínez Montañés (polychromer unknown), Christ of Clemency, 1603, detail, polychromed wood, height 190 cm, Seville Cathedral.

Source: akg-images / Album / Oronoz.

The stipulations set down in the contract have been adhered to: Christ’s flesh is indeed still pink with the warmth of life so that he can grant forgiveness to the sinner at his feet. You may remember that we examined another seventeenth-century polychrome sculpture – Gregorio Fernández’s, Dead Christ, c.1625–1630 – in Chapter 2, paying particular attention to the materials, techniques and processes involved in its creation. Christ of Clemency is also polychrome, and the painter’s use of chiaro- scuro only heightens the figure’s realism and further suspends our disbelief. Three-dimensional tears roll down Christ’s face, appearing as if about to fall through real space to reach the patron in a moment of forgiveness. In Christ’s eyes there is an incredible alertness; in his raised eyebrows the knowledge of a significant moment; in his open mouth a message of forgiveness. This is an example of artists breaking with traditional depictions of Christ on the Cross in response to the specific demands of a patron, a patron who in this instance commissioned a work to fulfil his private need for redemption.

Patronage in the Eighteenth Century

Worldly motives

The relationship between an artist and his patron can be a fickle affair, and political allegiances may alter it over time. You may remember Jacques-Louis David’s masterful ‘history’ painting Oath of the Horatii, 1784, examined in Chapter 1. The story is from Antiquity and was a royal commission for King Louis XVI. It was not long, however, before the artist would turn his back on his royal patron and, in 1792, sign the king’s death warrant. During the French Revolution, David (1748–1825) joined the Jacobins, led by Robespierre (the man responsible for the Reign of Terror), and found himself as deputy in the Republican National Convention. It was during David’s involvement with the Jacobins that he painted another image with which you will be familiar from Chapter 1, The Death of Marat, 1793.

Figure 5.10 | Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793 (stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday, Paris, 13 July 1793), oil on canvas, 165 × 128 cm, Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts.

Source: akg-images / André Held.

According to historian Simon Schama, when David presented Marat to the Convention he said: Citizens, the people … yearn to see once more the features of their faithful friend. David, they cry, seize your brushes, avenge our friend. Avenge Marat … I heard the voice of the people. I obeyed (Schama, The Power of Art, p. 224).

The motive for David and the Convention was thus political propaganda: to promote the Jacobin, Jean-Paul Marat, and to perpetuate pro-revolutionary zeal. However, the idealised image of Marat, the journalist and co-conspirator of the Terror, would eventually haunt David: Robespierre, the revolutionary leader behind the execution of tens of thousands of civilians, was put to death, and David, lucky to be alive, was disgraced by his association with these two figures.

Not all patrons are religiously or politically motivated, however, and throughout history works of art have been commissioned for a variety of reasons. George Stubbs (1724–1806) painted Whistlejacket, c.1762, for the Marquess of Rockingham, the owner of this chestnut stallion. What motive did the Marquess have for commissioning such a painting of his horse? Using the Toolbox provided at the start of the book, what is it about this particular representation of a horse that indicates the patron’s feelings towards it?

The eighteenth century was the epoch of the horse, and racing and breeding were the pursuit of the aristocracy. Whistlejacket is depicted as though he is an individual sitting for a portrait. Painted life-size on a monumental canvas, he is a testament to the wealth and élite social class to which his owner belonged. In this sense, the message of Whistlejacket is similar perhaps to that of Gainsborough’s painting Mr and Mrs Andrews (examined briefly in Chapter 1): both were painted as manifestations of their patrons’ successes. The motive was personal, egotistical and competitive.

The sheen of Whistlejacket’s well-groomed coat, his confident rearing posture and the dynamic flash of white in his eye all convey his character but also his patron’s status. Depicted with anatomical perfection, he conveys an image of athletic health. Compositionally isolated against a plain background, this chestnut stallion leaves the viewer in little doubt that they are looking at a ‘champion’ – as was certainly intended.

Figure 5.11 | George Stubbs, Whistlejacket, c.1762, oil on canvas, 292 × 246.4 cm, London, National Gallery.

Source: The National Gallery, London / akg-images.

The Modern Artist and the Market in the Nineteenth Century

Solitary and against society?

Patronage and the status of the artist are concepts that evolve over time (as outlined in the Introduction to this chapter). Art was largely commission-based from the medieval period to the eighteenth century, at which point people began to be interested in acquiring works of art for their homes. The founding of auction houses, such as Sotheby’s in 1744 and Christie’s in 1766, to sell art commercially is evidence of this new development – something that strengthened in the nineteenth century with the rise of wealthy industrialists and a strengthening middle class. As Jonathan Harris puts it:

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries this dominant patronal relation broke down and artists began to produce works increasingly for what was (and still is) called the ‘free market’: a system or network of now largely socially unconnected artists, buyers, sellers, and influential intermediaries (such as dealers, agents, and critics). (Harris, Art History: The Key Concepts, p. 229)

As the control that patrons typically had over artists was gradually relinquished, artists began to enjoy the freedom to express themselves more subjectively than ever before. The role of art critics became increasingly significant. Their judgements, published in newspapers and journals and widely disseminated, soon demonstrated the power to ruin or launch an artistic career. Art critic and poet Charles Baudelaire was an early champion of Manet and the Impressionists. Twentieth-century art critic Clement Greenberg not only championed the Abstract Expressionists, particularly Jackson Pollock, but, as we shall see, even attempted to define Modernism itself. Before exploring these developments, let us first examine the roots of the myth of the modern artist as a solitary and heroic individual.

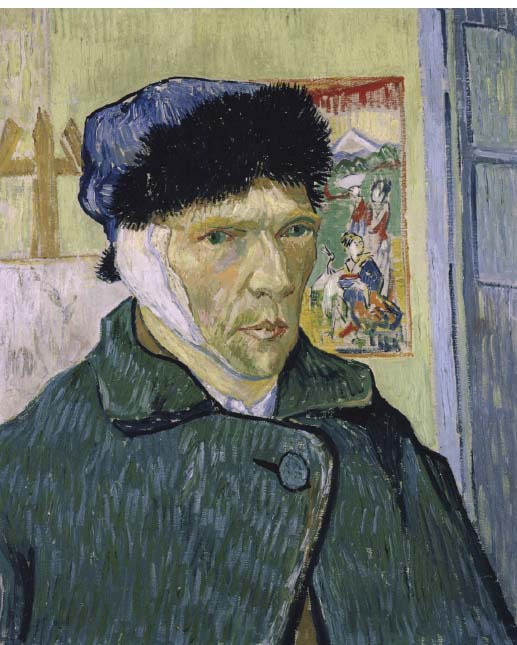

Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) exemplified the expressive qualities that may be seen in landscape painting, as we saw in the discussion of Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, in Chapter 1. In Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, the artist confronts us with the image of the artist as a solitary individual, while his bandaged ear, supposedly the result of a self-inflicted injury, tells, perhaps, of the personal cost at which such radical individualism was sustained (Figure 5.12).

The image is unnerving because a lonely and possibly mentally disturbed man looks back at us, but at the same time the image can be placed in a tradition of heroic artistic self-portraits, going back to the Renaissance. Remember the Self-Portrait, 1500, by Albrecht Dürer? The artist was daring enough to portray himself as unmistakably Christ-like. Arguably, Van Gogh is following artistic tradition here in presenting himself as an isolated figure with piercing eyes and an aura of martyrdom.

In 1888, he travelled to Arles in the south of France in the hope of collaborating with artist friends, especially Paul Gauguin. Unfortunately, the trip didn’t end well. The story goes that Van Gogh attempted to attack Gauguin with a razor which predictably precipitated Gauguin’s premature departure.

Supposedly in remorse for his attack on his friend, Van Gogh cut part of his own ear off, cementing his mythological notoriety as a mad artist. Recently, however, the self-inflicted slice-wound to the ear has been disputed by academics Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans. In Van Gogh’s Ear: Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence the suggestion is that Gauguin inflicted the injury on his friend in a violent exchange and the pair then made a pact to remain silent on the issue (Kaufman and Lustig, ‘Van Gogh’s Ear’).

Figure 5.12 | Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, oil on canvas, 60 × 49 cm, London, Courtauld Institute.

Source: The Art Archive / Courtauld Institute London / Superstock.

Van Gogh’s life has been endlessly dissected and we’re bound to be fascinated by suggestions such as that he went without food, or even ate his own paints in periods of paranoid depression. The fact that he died after apparently shooting himself only sets the seal on his fame. However, scholars insist that in the months leading up to his death, he had been enjoying one of his most prolific periods of artistic output. He was not drinking at this time and his sobriety probably heightened his artistic creativity. Historian Simon Schama also attempts to dispel the black clouds from our interpretation of the artist’s work and convincingly disputes the myth that the artist’s demise was inevitable:

In May 1890, the last springtime of his life, everything seemed to be going right for Vincent van Gogh. He was no longer neglected … In Brussels his paintings had been shown alongside works by Cézanne, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. One of them, The Red Vineyard, 1888, had even been sold for 400 francs … In the Mercure de France an influential young critic, Albert Aurier, had praised him to the skies. (Schama, The Power of Art, p. 298)

In truth, we will never really know the reason why Van Gogh pulled the trigger on himself in the wheatfield that day (if indeed he did). The gun shot wasn’t fatal: it was aimed below the chest, missing all his vital organs. In fact it seems very likely to have been the subsequent mismanagement of his care by homeopathic practitioner Dr. Gachet that ultimately killed him. We can only speculate about the success he might have enjoyed in his own lifetime had it not been cut short.

Financial worry almost certainly contributed to his malaise; and the lack of secure patronage contributed to this. Feminist art historian Griselda Pollock points out that it is not strictly true that Van Gogh did not have a patron, because in 1883 he entered into a dealer’s contract with his brother Theo, who provided him with a fixed monthly income. Poverty seemed to beckon, however, when Vincent overspent on costly pigments such as ultramarine. In a letter to his beloved brother, Theo, the artist wrote:

I dare hope the burden will be a little less heavy for you, I even hope much less heavy.

I realize, to the point of being morally crushed and physically drained by it, that taking all in all, I have absolutely no other means of ever recovering what we have spent.

I cannot help it that my pictures do not sell well.

The day will come, however, when people will see they are worth more than the price of the paint and my living expenses, very meagre on the whole, which we put into them. (Van Gogh, ‘To Theo van Gogh’)

It is sad to reflect on the way that money worries haunted Van Gogh during his life, given the astonishing sums that his works fetch now. Van Gogh’s Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers, 1888, was unsold during the artist’s impoverished lifetime but more than 100 years later, in 1987, it sold for £24.75 million ($39.7 million). This astonishing price tripled the previous record and heralded a new era of super-priced art works in the twenty-first century. Cynically, it is in the commercial world’s interest to perpetuate the myth surrounding artists like Van Gogh – his personal life makes him very saleable.

What the case of Van Gogh shows us is that in modern times, tremendous market value, recognition and success are dependent not necessarily on a patron but rather on powerful and wealthy collectors and museums vying for the most saleable commodity. Less than eight months after the sale of Van Gogh’s Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers, 1888, its record price was topped by the sale of another of Van Gogh’s flower paintings:

Van Gogh’s glowing ‘Irises’ – painted in 1889 during the artist’s first week at the asylum at St.-Remy – was sold at Sotheby’s in New York last night for $53.9 million, the highest price ever paid for an artwork at auction. The sale of 100 artworks, in which 75 were sold, totalled $110 million, a record total for an art auction.

The fierce bidding for the Van Gogh masterpiece was witnessed by an international gathering of about 2,200 collectors, dealers, museum curators and officials, a standing-room-only crowd that watched the proceedings in person and over closed-circuit television. (Reif, ‘Van Gogh’s “Irises” Sells for $53.9 Million’)

Van Gogh did not work to commission. A patron, other than his brother, might have been his financial saviour but undoubtedly his unpredictable temperament would have made a patronal relationship difficult. Indeed, patronage of the kind we encountered early on in this chapter seemed a thing of the past by the nineteenth century.

Twentieth Century

Figure 5.13 | Peggy Guggenheim.

Source: Photo by Frank Scherschel /The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images.

Collectors and critics

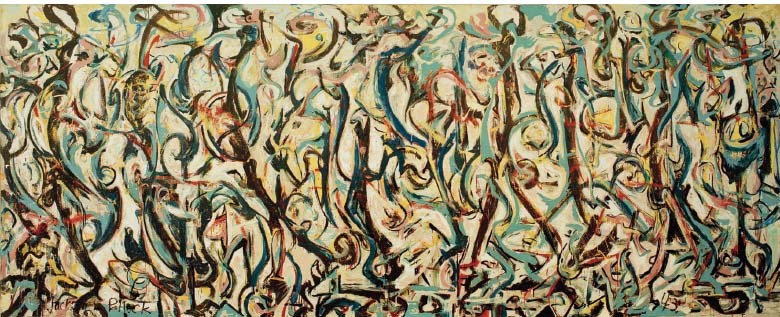

In the twentieth century, the system by which artists derived a living changed. Rather than patrons commissioning specific works of art, it was increasingly the case that artists created works according to their own expressive and compositional decisions, which were then sought out and purchased by collectors. It was therefore the collectors who enhanced the status and commercial fortunes of particular artists, but they were, in turn, influenced by the judgements made in print by prominent critics. This can be seen, for example, by studying the way in which Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), the famous mid-century Abstract Expressionist, rose to prominence. Pollock was the enfant terrible of the art world, a womaniser and an alcoholic. His untimely death in a car accident at the age of 44 made him a media icon. Unlike Van Gogh, however, he enjoyed tremendous fame and fortune during his own lifetime, thanks in part to the efforts of the critic Clement Greenberg and the collector Peggy Guggenheim.

Peggy Guggenheim (1898–1979) was an American art collector and gallerist, the niece of the well-known art collector Solomon R. Guggenheim. During the 1930s she lived in France and collected largely European works, principally by Cubist and Surrealist artists. After the Second World War, she became a champion of American painting. Countless mid-twentieth century American artists received her patronal support. She lived a privileged life and gained an international reputation for serious collecting in a male-dominated profession. With no papacy or royal family, America relied on collectors like Guggenheim to form the basis of their collections. She is credited with discovering the iconic American Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, and her significant private collection in Venice continues to draw visitors from all over the globe.

In 1943 Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Pollock to create Mural, a vast painting (on canvas) for her new house in New York. Apart from the enormous scale of the canvas, she left its style and content up to the emerging new ‘genius’ she had just discovered. The freedom this modern patronal relationship accorded the artist, which Pollock himself described as having ‘no strings’ attached to it, was unrecognisable by comparison to those in previous centuries (see the article on the University of Iowa Museum of Art website ‘More about Mural’).

Pollock’s status was partly attributable to his innovation, which was acknowledged by fellow Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning: Every so often, a painter has to destroy painting. Cézanne did it. Picasso did it with Twentieth Century Patronage and the Social and Cultural Status of the Artist Cubism. Then Pollock did it. He busted our idea of a picture to hell. Then there could be new paintings again (quoted in Hatje Cantz, ‘Action-Painting’).

He was the ‘bad-boy’ genius, a heady commercial combination. And the involvement of the media perpetuated the myth, giving him the nickname ‘Jack the Dripper’.20

Figure 5.14 | Artist Jackson Pollock painting in his studio.

Source: Photo by Martha Holmes /The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images.

Guggenheim’s patronage was certainly important, but it was also Clement Greenberg’s critical support that helped ensure lasting and iconic success for Pollock. Famously, and at a very early point in Pollock’s career, Greenberg hailed him as the ‘greatest painter of the age’. Equally importantly for our purposes in this chapter, the terms in which Greenberg hailed Pollock helped to establish a new appreciation of the formal qualities of an artwork rather than what it might represent – and this led to a new value being given to art as a cultural activity.

Greenberg’s theory of Modernism hinges on the importance of formal properties of artworks such as colour, line, space and composition. He claims that modernist painting remains true to its medium and that modern artists focus on the effects of their chosen medium alone. Thus, modern painting draws attention first and foremost to its pigment, its flatness, rather than seeking to trick the viewer into reading illusionistic properties in an object. Greenberg saw a linear progression in the history of art to the point where painting had ‘purified’ itself by concerning itself only with its own medium. He saw this as, in effect, a march towards abstraction and ‘flatness’. For him, Pollock’s use of paint represented a real truth to medium – brown, white, grey and black, dripped from a can in as unmediated a way as possible. Accordingly, he saw Pollock as the most important painter of his age – the one who captured the modern experience – the Zeitgeist. In 1948 Greenberg wrote:

Figure 5.15 | Jackson Pollock, Mural, 1943, oil on canvas, 247 × 605 cm, Iowa City, University Museum of Art. Gift from Peggy Guggenheim.

Source: akg-images / ©The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015.

Figure 5.16 Art critic Clement Greenberg.

Source: Photo by Leonard Mccombe /The LIFE Images Collection / Getty Images.

Isolation, or rather the alienation that is its cause, is the truth – isolation, alienation, naked and revealed unto itself, is the condition under which the true reality of our age is experienced. And the experience of this true reality is indispensable to any ambitious art. (Quoted in Wood, Frascina and Harrison, Modernism in Dispute: Art Since the Forties, p. 153)

Greenberg championed the Abstract Expressionists as Charles Baudelaire had championed the Impressionists nearly a century earlier. Baudelaire’s prime value was ‘the transitory’; Greenberg’s was ‘medium-specificity’. The belief, shared by modernist critics a century apart, that art’s chief value is in its ability to capture and express its moment, was a new and significant claim concerning the status of art in society.

During his lifetime, Pollock’s paintings made the artist hugely famous and earned him a feature article in the magazine Life in the 8 August 1949 issue, with the title, ‘Jackson Pollock: Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?’ Nevertheless it was only after his death that his works began to reach the astronomical values they claim today. In 2006 Sotheby’s sold Pollock’s Number 5, 1948, for $140 million.

The Contemporary Artworld

The artist as celebrity and the rise of the supercollector

Pollock didn’t particularly seek self-promotion and, arguably, the pressure he felt as a result of his fame contributed to his unhappiness before his untimely death. Nevertheless, self-promotion and the technological means with which to do it is arguably the hallmark of the media-saturated twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

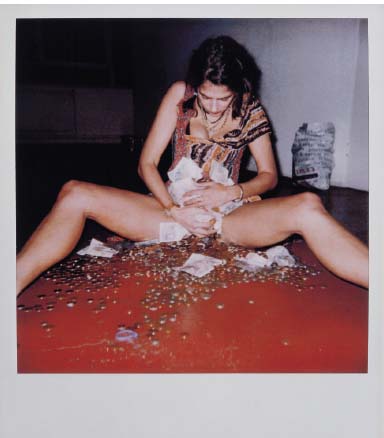

We have already examined the changing status of the artist from the Middle Ages through to the Renaissance, and witnessed the birth of the artist as celebrity, but in modern times this celebrity has taken on almost epoch-defining proportions. The contemporary British artist Tracey Emin (born 1963) has received a series of institutional honours and been granted a number of solo exhibitions. Yet her high profile and newsworthy status could arguably be ascribed to her representation of taboo subjects, her sensational autobiographical subject matter and her former ‘bad girl’ lifestyle, as much as to serious critical and public admiration of her art. Perhaps the most significant factor that helped shape her success was the relationship that was made over many years with the collector Charles Saatchi.

Figure 5.17 | Tracey Emin, I’ve Got It All, 2000, ink-jet print, 124 × 109 cm.

Source: ©Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2015. Image courtesy White Cube.

As well as taking part in iconic group exhibitions such as ‘Sensation’, 1997, and the Turner Prize, 1999, the artist has enjoyed a number of solo exhibitions including: ‘My Major Retrospective (1982–1992)’, 1994; ‘I Need Art Like I Need God’, 1997; ‘Tracey Emin Museum, 1995–1997’; ‘Sagacho Space’, 1998; ‘Everyone’s Bleeding’, 1999; ‘You Forgot to Kiss My Soul’, 2001. She also represented Britain in the Venice Biennale and collaborated with the internationally acclaimed artist Louise Bourgeois in the exhibition ‘Do Not Abandon Me’, 2010.

Emin’s distinctive persona and commercial success have provided her with the opportunity to model for controversial clothes designer Vivienne Westwood. I’ve Got It All, 2000, features Emin sitting on the floor with open legs framing and almost consuming her independently earned wealth. Its blatant vulgarity is characteristic of the artist’s oeuvre. The money, together with the artist’s designer dress, is thought to relate to Emin’s recent financial success and public recognition, but they jar with the basement-style space in which she sits. Professor Peter Osborne describes the work’s connotations in terms of:

a certain tabloid triumphalism of the ‘loadsamoney’ variety. (Pictures of pools/lottery winners covered in cash – sometimes posed naked on beds – are a staple of British tabloid journalism.)

… The artist is wearing a Vivienne Westwood dress … Designer clothing was at the forefront of the consumer booms of the 1980s and 1990s … Emin’s dress, then, is a sign of success … she has crossed the divide from the ordinary (the world of that carrier-bag, the high street) to the extraordinary (the dress and the occasions to wear it) and both must be present in order to see it. (Townsend and Merck, The Art of Tracey Emin, pp. 45, 55)

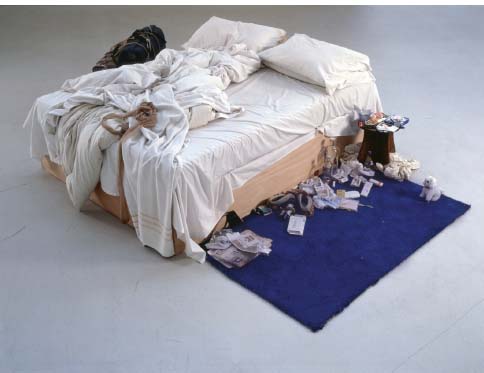

Figure 5.18 | Tracey Emin, My Bed, 1998, mixed media (mattress, linens, various memorabilia), maximum width 234 cm.

Source: ©Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2015. Image courtesy Saatchi Gallery, London. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

The installation My Bed, 1998, shown at Tate Gallery in 1999 as part of Emin’s Turner Prize-nominated exhibition, is a confessional work with a supposedly autobiographical representational value. It stems, apparently, from a dark episode in the artist’s life and is said to represent four days she spent under the covers, con-templating suicide. The installation had no patron, but it sold to art collector and gallery owner Charles Saatchi for £150,000 on the secondary art market; Emin’s bed became Saatchi’s bed overnight.

Saatchi – who supposedly out-bid Tate to acquire My Bed for his collection – represents the continued ascendency of private enterprise and commerce in the face of the continuing demise of state patronage. He was born in Baghdad in 1943 but his family left their native Iraq and arrived in London in 1946. He made his fortune from the advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi, which he established with his brother, Maurice, in 1970. In 1978, Saatchi & Saatchi changed political advertising with their epoch-defining poster ‘Labour isn’t working’; its sub-title read ‘Britain’s better off with the Tories’. Their campaign helped to bring the Conservatives, led by Margaret Thatcher, to power. In turn, the agency itself became a super-brand and the Saatchi brothers were propelled to the international forefront of advertising.

It is not the case that Saatchi has shaped the contemporary art world entirely in his image. Rather, it seems that his interest was piqued by a generation of young artists, Emin and Damien Hirst among them, who already seemed to share his interests (not least in making money) and his market-orientated world-view. Saatchi’s first serious art collection was housed in the Saatchi Gallery in Boundary Road, London, and one of its first exhibits was the installation A Thousand Years, 1990 by British artist Damien Hirst (born 1965). Until their professional relationship ended in 2003, Saatchi was Hirst’s most constant patron and is widely believed to have been responsible for the young maverick’s fame and fortune. Hirst was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1992, winning the competition in 1995 with Mother and Child, Divided, 1993. His diamond-encrusted skull For The Love of God, 2007, is reported to have sold for £50 million – a breath-taking testament to materialism.

The rise of Hirst demonstrates the flowering of the kind of celebrity status found in seed form in the Early Renaissance. Furthermore, in Hirst was born the idea of artist as curator: in 1988, while still a student at Goldsmiths College, he conceived and curated the critically acclaimed ‘Freeze’ show in London’s Docklands. Saatchi visited the exhibition and a famous collaboration between the pair ensued, leading to multi-million pound success and lasting celebrity. The relationship could be considered analogous to that between the High Renaissance master Michelangelo and Pope Julius II; certainly both were self-promoting, celebrity-making, tempestuous and historically significant in terms of creating an artistic legacy.

It is not so much the mansion he owns or the hundreds of millions he is worth that matter, says Damien Hirst, it is the recognition they bring that counts.

(Brooks, ‘It’s the Fame I Crave, Says Damien Hirst’)

Unlike in the quattrocento, however, the twentieth- and twenty-first-century art markets are aided by ‘the dealer’. In the early 1990s Hirst was represented by dealer Jay Jopling and one of the most famous triangles in the art world was in operation: Damien Hirst, the shock-tactic artist; Charles Saatchi, the patron/supercollector; Jay Jopling, the charismatic dealer. An amalgam of artistic controversy, marketing might and the power to set trends was a fortune-winning formula, as gallerist and writer Gregor Muir describes:

As the nation’s economy staggered through the Nineties, Saatchi found an explosion of talent on his own doorstep. What was more, the artists were producing reasonably priced work. As his attentions turned from New York to London, Saatchi started to buy up the block. Enter Jay Jopling, the perfect dealer for the Saatchi era – and what better artist to take on than Hirst? The Holy Trinity had arrived: artist, dealer, and collector, all destined to become key figures in the history of young British art. (Muir, Lucky Kunst: The Rise and Fall of Young British Art, p. 36)

The relationship between Hirst and Saatchi was also shaped through a series of eye-catching public exhibitions, indicating the increasing influence that such public displays had on the status of both art and individual artists in this period. In 1990 Hirst co-curated ‘Gambler’, a show from which Charles Saatchi acquired A Thousand Years, 1990, a double-chambered glass case which enclosed the severed head of a cow in one compartment, maggots, flies and an insect-o-cutor in the other. The stench from the rotting head made the artwork notorious but it also necessitated its prosthetic substitute. It was one of many of the artist’s identity-defining animal installations. Hirst would win the Turner Prize five years later with an animal-based artwork, demonstrating once more the brevity of life and the inevitability of death.

Figure 5.19 | Damien Hirst, AThousand Years, 1990, glass, steel, silicone rubber, painted MDF, insect-o-cutor, cow’s head, blood, flies, maggots, metal dishes, cotton wool, sugar and water, 207.5 × 400 × 215 cm.

Source: © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2015. Photo: Roger Wooldridge.

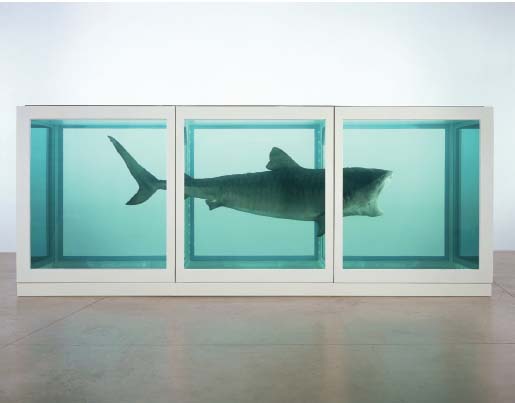

Falling under each other’s spell, Saatchi offered to purchase whatever Hirst chose to create for the Saatchi Gallery’s exhibition ‘Young British Artists’ in 1992. Saatchi’s large north London space allowed for large-scale installations in a wide range of media. The show featured Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991, and A Thousand Years, 1990. The former, the show’s signature work, became an international art icon, an emblem of the YBA (Young British Artists) and synonymous with its patron. Saatchi had secured the ‘bad boy’ of art – and newsworthy visuals to match. A 14 foot Australian tiger shark suspended in a vitrine of formaldehyde was the ultimate, updated memento mori.

Gregor Muir sums up well the notoriety and critical dismissal of Hirst’s shark:

Everyone knows Hirst’s ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’, the tiger shark in a glass tank filled with water and formaldehyde. Otherwise known as ‘the shark’, it has embedded itself in the public imagination to such a degree that it might be said to be the contemporary equivalent to the ‘Mona Lisa’. Commissioned by Charles Saatchi for £50,000, it caused a public outcry when it was finally unveiled at the Boundary Road Gallery. This wasn’t art! At best, it was inhumane. More importantly, how much did it cost? ‘The Sun’ newspaper paraded the headline ‘£50,000 for Fish without Chips’. Needless to say, thanks to the ensuing furore, Hirst broke through the barrier of an otherwise clandestine art world and became a household name. (Muir, Lucky Kunst: The Rise and Fall of Young British Art, p. 44)

Hirst’s rise to fame, and the rise to prominence of the Saatchi artists more generally, were aided by two further key artistic institutions of the 1990s, both of which chimed with the mood of the times: The Turner Prize and Goldsmiths College. The Turner Prize, sponsored by Channel 4 Television, was founded in 1984. In a bid to enthuse the collectors of the future, the organisers enlisted the media to raise the profile of contemporary British art, which had always courted controversy and media attention. The 1995 Turner Prize exhibition attracted unprecedented numbers of visitors who queued daily to see the work of the shortlisted artists. Many were curious to see Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child, Divided which created a tidal wave of tabloid excitement: Have they gone stark-raving mad? The Turner Prize for Modern Art (worth £20,000) has gone to Damien Hirst, the ‘artist’ whose works are lumps of dead animals (Button, The Turner Prize: Twenty Years, p. 112).

Figure 5.20 | Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991 (sideview), glass, painted steel, silicone, monofilament, shark and formaldehyde solution, 217 × 542 × 180 cm.

Source: © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2015. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

Figure 5.21 | Marcus Harvey, Myra, 1995, acrylic on canvas, 396 × 320 cm.

Source: Image courtesy of Marcus Harvey and Vigo Gallery. © Marcus Harvey.

All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015.

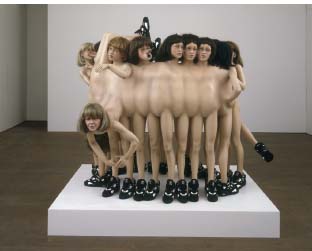

Figure 5.22 | Jake and Dinos Chapman, Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic, and De-sublimated Libidinal Model (Enlarged × 1000), 1995, fibreglass, resin, paint, wigs and trainers, 150 × 180 × 140 cm.

Source: © Jake and Dinos Chapman. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015. Image courtesy White Cube.

The influence of Goldsmiths College, the equivalent of an educational super-brand for artistic impresarios, cannot be underestimated. Its art department is recognised internationally as fostering many of the generation of artists who became known as the YBA, and who dominated the Turner Prize nomination lists during the 1990s and beyond.

In addition to these institutions, the next important exhibition in this story was the non-Saatchi-curated, but wholly Saatchi-influenced ‘Sensation’, held at the Royal Academy in 1997.22 This show displayed 110 works by YBA from the Saatchi Collection, and it attracted both high levels of media coverage and public outrage. Indeed, it was probably its transgressive nature that made it commercially successful.

In the UK, it was Marcus Harvey’s Myra, 1995, juxtaposed with the Chapman Brothers’ sexually mutant children that caused a storm. The overtly paedophilic associations of the latter made a latent connection with Myra Hindley’s role in the sickening murder of five children. According to lecturer, writer and curator Julian Stallabrass: In a curatorial strategy that Saatchi was very likely to have influenced, the child murderer Myra was hung adjacent to the Chapman Brothers Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic, and De-sublimated Libidinal Model (Stallabrass, High Art Lite: The Rise and Fall of Young British Art, p. 213).

Artist Jenny Saville (born 1970), examined in Chapter 1 and Chapter 6, has enjoyed seven solo exhibitions since 1996, and her commercial success has been largely attributed to Saatchi; she was one of his early protégés. He is said to have first spotted her work at the ‘Critics’ Choice’ show in 1993, whereupon he commissioned 15 of her paintings for the Saatchi Collection and put her on the road to financial security and wider recognition. In the ‘Sensation’ exhibition, Saville’s controversial nudes fuelled media interest and perpetuated the success of Saatchi’s new acquisitions. Artist and collector became inextricably linked. Was it the case that Saville had to relinquish a degree of control as a result, however:

I just heard today that Saatchi has put frames round most of my paintings … Now that’s not the point – the figures are supposed to challenge the edges of the canvas. Putting a boundary around them just gets them wrong … I want to make an installation out of this painting [that is, ‘Strategy’, 1994] – put a mirror across the gallery so the viewer can read the reversed text. But I’m having to really fight to make that happen. (Hatton and Walker, Supercollector: A Critique of Charles Saatchi, p. 154)

As we established at the beginning of this chapter, a patron’s motivation for commissioning a work of art or architecture is an important issue. So, what are Saatchi’s motives for patronage and collecting? Gordon Burn indirectly asked Saatchi this very question:

First question [from Burn]: Would he describe his collecting as: (a) a hobby; (b) an obsession; (c) a dalliance; (d) an investment opportunity; (e) a bid for immortality?

And the message came back [from Saatchi]: all of the above apart from (e). (Burn, Sex & Violence, Death & Silence, p. 290)

Like the Medici family in Renaissance Italy, who were businessmen with ambition to rule a city and invest in their cultural legacy, Saatchi is both increasing his private fortune and making his own impact on the history of British art. While a patron supports an artist financially and may have some influence over the work as a result, a collector buys work indirectly on the secondary market via auctions and galleries. Nevertheless, when a collector is wealthy enough to out-bid the competition, and to buy (and then sell) en masse many or all of an artist’s works, he or she exerts comparable influence to that of a traditional patron. According to Hatton and Walker, because Charles Saatchi is both patron and collector, he is classed as a ‘supercollector’.

Saatchi’s purchasing strategy has been of great importance both to individual artists in establishing their careers and in helping to establish the status of British art as at the forefront of international trends and the international market. If Saatchi had not provided this support, would anyone else have done so? And would British art today be as internationally successful as it is?

Whatever you think of Charles’s taste for dots, unmade beds, discarded condoms, pickled sharks, bisected cows, frolicking child mannequins with penises for noses, there’s no doubt that, under his patronage, London has become Europe’s – perhaps the world’s – modern-art capital. (Aldridge, ‘Ad You Like It: The Bloody Battle Between the Saatchis’).

However, according to late journalist and author Gordon Burn, Saatchi not only has the ability to ‘make’ an artist, but also to ‘break’ them:

[b]eing taken up by Charles Saatchi has become one of the conditions of success for an artist in recent years. Being dropped by him, it is now becoming clear, can have equally devastating repercussions. (Burn, Sex & Violence, Death & Silence, p. 291)

Charles Saatchi, the supercollector of the twentieth century, presumably reflects upon his status, and, as Hatton and Walker point out in their socialist critique of him, his purchase of Ashley Bickerton’s The Patron, 1997, is perhaps a sign of growing self-awareness and a willingness to tolerate criticism (Hatton and Walker, Supercollector: A Critique of Charles Saatchi, p. 186).

It is certainly unlikely that Julius II would have purchased such a damning critique of his own monumental cultural investment.

Figure 5.23 | Ashley Bickerton, The Patron, 1997, oil, acrylic, pencil and aniline dye on wood, 167.5 × 228.5 cm.

Source: Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

In July 2010 Saatchi announced that he was donating his gallery’s collection to the nation. What are we to make of this philanthropic contribution? Recently, he has created new ways for artists to show their works for free, online, via his website. His facilitation of a free exhibition website allows over 100,000 artists to sell their work directly without incurring commission fees.

Saatchi appears to consider this kind of direct, artist-to-audience – and potentially artist-to-buyer – viewing as enabling artists to escape potentially constraining relationships to patrons, collectors or dealers. He also appears to view it as indicating the obsolescence of art criticism. On the role of the critic, Saatchi, perhaps ironically, comments as follows:

[N]o one critic matters that much, whatever their credentials … The days when critics could create an art movement by declaring the birth of ‘Abstract Expressionism’, Clement Greenberg-style, are firmly over. (Saatchi, My Name Is Charles Saatchi and I Am an Artoholic, p. 97)

In seeming confirmation of this viewpoint, Saatchi has diversified not only via his website, but also onto television. The BBC TV reality show The School of Saatchi, screened in 2009, was a talent competition strangely reminiscent of that staged by the guilds in Renaissance Florence for the Baptistery doors. Artists competed for the chance to be exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery and to have a studio space for three years. Suddenly, the trail from the Medici to Saatchi seems less obtuse.

Many of the factors arising from and influencing patronal relationships, and the intersection of and potential tensions between the interests of the public, specialist critics, private patrons and state institutions, can also be seen in the case of architectural commissions.

Architectural Landmarks in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Figure 5.24 | Rogers and Piano, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 1971–1977.

Source: © digitalimagination / iStockphoto.

Enhancing corporate ‘brands’ through association with ‘star’ architects

Several of those buildings already discussed in other chapters in this book can be looked at in terms of patronage and the social and cultural status of the architect. For example, the close patronal relationship between architect Philip Webb and patron William Morris in the Red House; between Le Corbusier and the Savoye family in Villa Savoye; between Frank Lloyd Wright and Edgar Kauffmann Snr. in Fallingwater, and between Richard Rogers and Lloyd’s of London in the Lloyd’s Building, to name but a few. For the purpose of illustration, let’s take a closer look at the patronal relationship that existed between Richard Rogers and his client, Lloyd’s of London, and the extent to which Rogers’ social and cultural status helped him to secure the commission.

British architect Richard Rogers was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1981, and became Baron Rogers of Riverside in 1996. His awards include: RIBA Gold Medal 1985; Thomas Jefferson Medal 1999; Stirling Prize 2006, 2009; Minerva Medal 2007, and Pritzker Prize 2007. When insurance giant Lloyd’s commissioned Rogers to redevelop the existing Lloyd’s site, he had already achieved a degree of fame for his work with Renzo Piano on the Pompidou Centre in Paris, 1971–1977; many more accolades were to follow the Lloyd’s commission.23 The Pompidou Centre is an iconic landmark today, but back in the 1970s its high-tech design was given the derogatory label ‘Bowellism’ by its critics because they said the many pipes on the outside of the building looked like intestines. Rogers developed this style (not that he labelled it high-tech himself) further to make his famous London landmark. Lloyd’s, a powerful corporate brand and risk-taking business, adopted a very effective PR campaign when they hired such a well-known and risk-taking architect.

On the role of the architect in relation to the patron, Rogers states:

Buildings are not idiosyncratic private institutions: they give public performances both to the user and the passer-by. Thus the architect’s responsibility must go beyond the client’s program and into the broader public realm. Though the client’s program [sic] offers the architect a point of departure, it must be questioned, as the architectural solution lies in the complex and often contradictory interpretation of the needs of the individual, the institution, the place and history. (In Campbell Cole and Rogers, Richard Rogers + Architects, p. 19)

In conclusion, our interpretation and understanding of any given work is dependent on a number of related factors. Chapter 3 focused on the formal aspects of works of art, paying very little attention to the artist’s biography or the social and historical context of their creations; Chapter 4, meanwhile, focused specifically on the social and historical context of art and architecture, often at the expense of formal analysis. Art history involves learning about all of these, often inter-related, factors and asking how they affect our interpretation of works. In this chapter the themes of patronage and the social and cultural status of the architect have been examined separately yet, inevitably, in close relationship with one another.

Figure 5.25 | Richard Rogers, Lloyd’s Building, City of London, 1978–1986, façade with atrium.

Source: © Robert Harding Picture Library Ltd / Alamy.