Chapter 6

Gender, Nationality and Ethnicity

Introduction

This chapter introduces you to the important concepts of gender, nationality and ethnicity and considers how they may be significant for the interpretation of works of painting, sculpture and architecture. These themes have been explored in a variety of different ways by artists, both consciously and unconsciously, and very often the different themes overlap in a particular work.

In the discussion of gender, the ideas of pioneering female artists and art theorists are examined in relation to gender relations in art-historical discourse and in relation to the representation of male and female bodies. Issues of power in relation to gender and art are also examined in terms of their symbiotic relationship with ethnicity, especially in early twentieth-century Europe.

The concepts of nationality and ethnicity are inextricably linked; both may be understood in the context of European exploration and colonial expansion. Nationality is examined primarily in relation to national monuments and the conscious decision of artists, sculptors and architects to create iconic emblems for their states.

In relation to ethnicity, the legacy of the colonial past is examined in terms of the unequal relationship that existed between the colonisers and the colonised in the early twentieth century, namely, White Europeans assuming supremacy over people from ‘other’ lands. Such discrimination was challenged later on in the century and different ethnicities were in some cases embraced by artists proud to claim a non-White identity. The label ‘other’ was considered to be a disadvantage, especially where White artists tended to assume no label at all.

While works are studied primarily for their content in terms of gender, nationality and ethnicity, their formal elements and materials, techniques and processes are, more often than not, inextricably linked to their meaning.

Gender: The Representation and Subversion of Gender Stereotypes

Figure 6.1 | Paul Joseph Jamin, Brenn and his Share of the Plunder (or Spoils), 1893, oil on canvas, 162 × 118 cm, La Rochelle, Musée des Beaux-Arts.

Source: akg-images.

Figure 6.2 | Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, portrait of Giovanni (?) Arnolfini and his wife Giovanna Cenami (?), oil on oak panel, 82.2 × 60 cm, London, National Gallery.

Source: National Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images.

Gender is a complex issue and best understood in relation to its difference from sex. What is the difference between sex and gender? What do we mean by femininity and masculinity? Gender commonly relates to what we understand as being either ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’. In this sense gender is socially and culturally constructed rather than biologically determined. For this reason, gender is often treated stereotypically. For example, women have often been shown in passive and subordinate positions in visual media, while men have typically been portrayed in active and powerful roles. This contrasts with a person’s sex, which is fixed; sex is a biological term used to classify human beings as either male or female. Our sex is determined by our physical difference at the level of our genitals and hormones.

A ‘woman’s place’ and the ‘male gaze’

Brenn and his Share of the Plunder, 1893, by Paul Joseph Jamin (1853–1903) epitomises the stereotypical portrayal of the sexes at its most basic. This work lends itself to what British feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey described as the ‘male gaze’: the conquering Gaul warrior stands erect and, having seized the palace, he is about to claim his prize: the semi-naked women within. In the canon, this work was celebrated as a history painting, but what is its real subject – eroticism, voyeurism and/or fetishism? The ‘male gaze’ controls the women as objects of desire and enables the spectator vicariously to share in the enjoyment of the spoils – provided, however, that the spectator imaginatively identifies with the male figure. How does the composition of this work help us to read the social and cultural status of the sexes at the time of its painting? What does this tell us about the perceived intended audience of such works?

Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, previously examined as an example of double-portraiture in Chapter 1, is revealing of the figures’ respective gender status. Art historians have determined that the woman, believed to have become Mrs. Arnolfini, is not depicted as pregnant, but the work seems to foreshadow her pregnancy with the abundance of fabric gathered boastfully around her middle. The oranges ripening on the window-sill serve as a symbol of her expected fertility, and St. Margaret (the patron saint of women in childbirth), whose image is carved on the chair positioned against the back wall (right), is a further symbol of her child-bearing role. The little dog, almost camouflaged against the wooden floor, stands between the couple apparently as an emblem of fidelity, a trait expected to characterise her marriage.24 A marital contract would ensure that Mr. Arnolfini’s wealth passed to his rightful heirs in the future. The shoes, however, are perhaps the most interesting of all in the context of gender; their positioning is, arguably, far from incidental. Her delicate little slippers find themselves trapped adjacent to the bed, barely distinguishable from their surroundings; Mr. Arnolfini’s, in stark contrast, find themselves almost illuminated in the foreground of the work, still slightly muddied from his recent excursion outdoors, demonstrating he has access to the public sphere of existence. The art historian Carola Hicks, noted a range of oppositions in relation to Mr. Arnolfini’s and Mrs. Arnolfini’s respective headdresses alone: black/white, cosmopolitan/local, up-to-date/old fashioned, dashing/demure (Hicks, Girl in a Green Gown, p. 28). Hicks also noted that Mr. Arnolfini’s tabard is lined with ‘marten fur’: hers from ‘cheaper squirrel’ (Hicks, Girl in a Green Gown, p. 23).

It would hardly win us respect if our wife busied herself among the men in the marketplace, out in the public eye. It also seems some-what demeaning to me to remain shut up in the home among women when I have manly things to do among men.

(Leon Battista Alberti quoted in Wigley, ‘Untitled: The Housing of Gender’, pp. 334–335)

From a feminist perspective, The Arnolfini Portrait can be read as a telling document of the inferior position of women in fifteenth-century Europe, although Chapter 1 notes the more recent reading of this work as Mrs. Arnolfini signing a business transaction that requires witnessing. Whichever our perspective, it is fair to say that patriarchy prevailed at this time across Europe and beyond. However, any reading of a work made so long ago, so far removed from the context in which we read it, cannot be treated as wholly accurate or finite.

The idea that a woman may feel trapped by domesticity is a common one, thought-provokingly described by feminist architectural historian Leslie Kanes Weisman:

A homemaker has no inviolable space of her own. She is attached to spaces of service. She is a hostess in the living room, a cook in the kitchen, a mother in the children’s bedroom, a lover in the bedroom, a chauffeur in the garage. The house is a spatial and temporal metaphor for conventional role playing. (Quoted in Weisman, ‘Prologue’, p. 2)

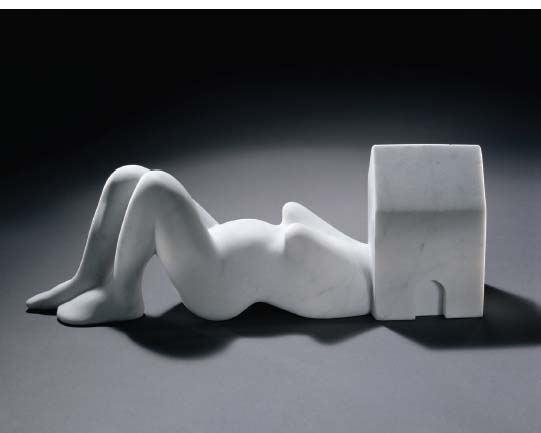

It was made manifest in marble five centuries after The Arnolfini Portrait in the work entitled Femme Maison, 1994, by French artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010).

Figure 6.3 | Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 1994, white marble, 11.4 × 31.1 × 6.6 cm.

Source: Photo: Christopher Burke, ©The Easton Foundation /VAGA, New York / DACS, London 2015.

A female form without arms lies trapped and anchored under that timeless symbol of domesticity – the house. Specifically, her head, the part of her anatomy most strongly associated with her personal identity, is trapped in the home; a fitting response to the axiom ‘a woman’s place is in the home’. American photographer and film director Cindy Sherman (born 1954) has based much of her work on the roles assigned to women in a ‘man’s world’. Her black and white film stills are specifically based on the stereotypical roles of women in old Hollywood movies. In each one of Sherman’s 69 black and white photographs that form her iconic Untitled Film Stills series, the artist masquerades as every conceivable cliché of constructed femininity. In Untitled Film Still #3, 1977, she’s the kind of wife ‘a man might long to come home to’: literally behind the kitchen sink, locked in the domestic sphere, all the while looking delectable and wanton; her self-embrace anticipating the touch of the male. The whole mise-en-scène is planned as meticulously as a film director’s. Every element, including the camera angle, the lighting, the make-up, the hair and the clothes, signifies its role in creating the myth of the feminine. Another in the series, Untitled Film Still #6, 1977, features the artist with deeply coloured lips, open mouth, carefully combed hair, and body sprawled in a state of undress across a bed. Together these features imply some sort of narrative we feel we should work out. The camera looks down on the figure from above, heightening her objectification. Look up Untitled Film Still #6. What persona is Sherman adopting here? The femme fatale? The starlet? Whichever the role, we feel we know the character, and we have certainly seen her type in films.

Despite Sherman’s role as the main character in these film stills, seldom does the artist reveal anything of herself – her actual rather than her constructed identity. Rather, she focuses on the way in which make-up, pose and costume help to construct a variety of socially acceptable identities for women, particularly in visual culture, where women have tended to be particularly objectified. Do you remember Jenny Saville’s Branded examined in Chapter 1 as an example of self-portraiture? Does Saville’s painting conform to or reject the ‘male gaze’? Do you think there Gender: The Representation and Subversion of Gender Stereotypes Gender, Nationality and Ethnicity is a corresponding ‘female gaze’ in recent times? And, is it necessarily liberating?

Figure 6.4 | Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #3 1977, gelatine silver print, 18 × 24 cm.

Source: Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures.

British film theorist Laura Mulvey, coined the term ‘male gaze’ in her 1970s critiques of visual culture and specifically of film. In her seminal work ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, 1975, she used psychoanalysis to examine the way film, through its editing and shot selections, constructs gender roles so that male characters are shown to gaze at and derive pleasure from the sight of female characters, noting that these roles are rarely reversed.

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining ‘male gaze’ projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ (Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, 1975).

Women are constructed as ‘objects’ of the ‘male gaze’, and male and female viewers alike must assume the imaginative position of the heterosexual male character in order to take pleasure in the sights the image offers. This is a gaze that women then internalise, as they learn to objectify themselves and turn a critical gaze on their own appearance and behaviour, seeking to bring it into conformity with the on-screen women. Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills show the artist taking on and exploring this internalisation of the ‘male gaze’.

Woman as ‘other’

Oath of the Horatii, 1784, by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825) (examined in some detail in Chapter 1 as an example of the ‘history’ genre) is a highly gendered image of the noble defence of pride and territory. The men, about to go to war, stand with tensed muscles, outward gaze and grounded feet. Even the colour palette selected to depict them is vibrant in contrast to the paler, more insipid hues of the women’s robes. The female group is depicted as sedentary, home-bound, with downcast eyes and weeping. Part of the tension in this work lies in the knowledge that one of the Horatii wives is the sister of a Curiatii enemy, and one of the sisters of the Horatii is soon to be married to one of the Curiatii, and so many of their tears are harbingers of lost love. Despite the emotional torment of the women, the men still go to war at the command of their father. David’s Neo-classical style conveys their impressive musculature with an almost photographic level of precision and polish, while their emphatic stances convey their readiness for battle.

The machismo in the Horatii is almost palpable; these brothers-inarms will proudly die in defence of their city. The masculine stereotype is a familiar one, and the modern tendency to ridicule it is not lost on American artist Barbara Kruger (born 1945). Kruger’s Untitled (We Don’t Need Another Hero), 1986, makes a playfully powerful statement about the polarity of gender in terms of the stereotypically assumed strength of men over women. The artist’s depiction of the youthful boy with cheeks about to burst with bravado indicates the historical socialisation of children into gender stereotypes and a 1980s’ critique of it. Kruger stated, I work with pictures and words because they have the ability to determine who we are, what we want to be, and what we become (Barbara Kruger quoted in Stedelijk Museum, ‘July 23: Appropriation’).

Figure 6.5 | Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 330 × 425 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Source: akg-images / Erich Lessing.

Figure 6.6 | Barbara Kruger, Untitled (We Don’t Need Another Hero), 1987, photographic silkscreen/vinyl, 228.6 × 297.2 cm, New York, Mary Boone Gallery, MBG#4186.

Source: Copyright: Barbara Kruger. Courtesy: Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

The repression of a man’s emotions and the injunction upon him to provide for all of his dependants are as potentially problematic for men as the more commonly discussed restraints have been for women. Perhaps the recently emerged ‘crisis of masculinity’ may suggest that the pendulum has now swung too far.

The issue of gender in relation to art history relates both to the portrayal of the sexes and the different fortunes of male and female artists. Women artists have historically been subjected to discrimination, for example. Nevertheless, there have been some notable exceptions. Feminist scholar Germaine Greer describes seventeenth-century Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi (the artist who painted Judith Slaying Holofernes; see Figure 4.3) as the exception to all the rules (Greer, The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work, p. 207).

La Loge, 1874, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), depicts the prettiest of women and the dandiest of men in a box at the Paris Opera – one of Paris’ newly built entertainment spaces in the mid-nineteenth century. The woman looks at us with sorrowful eyes; the man, meanwhile, looks at another woman, certainly not at the entertainment on stage (which would be below). His binoculars are practical and powerful; hers, in contrast, are decorative, and powerless.

Renoir’s subject matter was approached from a different angle by American artist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) in her painting In the Loge, 1878. Cassatt appears to have consciously subverted the ‘male gaze’ in her take on a theatre-box scene. By putting herself into the position of the male artist she actually subverts the ‘male gaze’. This lady has no frills, no pretty bonnet or flowers; she is a lone spectator of the show, buttoned up to the neck with emphatic control of the gaze – she is empowered – her vision is active not passive. As feminist art historian Linda Nochlin observed:

[The] woman … artist is merely ridiculous, but I feel that it is acceptable for a woman to be a singer or a dancer.

(Renoir (1888) quoted in Clark, Women and Achievement in Nineteenth-Century Europe, p. 82)

Cassatt … associated femininity and the active gaze. Her young woman in black, armed with opera glasses, is all active and aggressive-looking. She holds the opera glasses, those prototypical instruments of masculine specular power, firmly to her eyes, and her tense silhouette suggests the concentrated energy of her assertive visual thrust into space. (Nochlin, Representing Women, p. 194)

Cassatt was ahead of her time in achieving a measure of success as a woman artist. She was aided in her efforts by her independent wealth – poorer women had far fewer chances. Nevertheless, she used her position to explore the definition of bourgeois femininity with all of its contradictions. She said she wanted to be someone rather than something (Nochlin, Representing Women, p. 215).

Look again at Cassatt’s Lydia at her Tapestry Frame discussed in relation to its form and style in Chapter 3. This time examine the scene through the lens of gender.

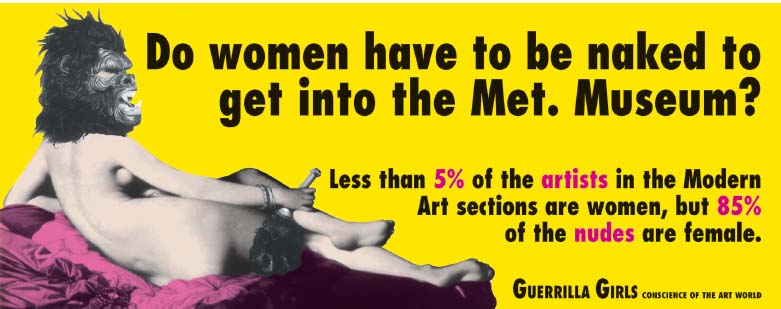

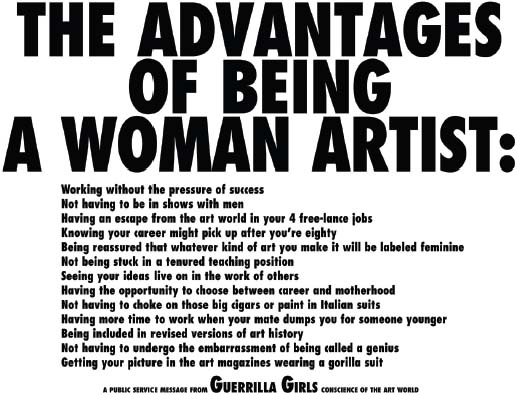

Cassatt’s In the Loge repositioned the nineteenth-century female subject as the one who can and is able to look for herself; Cassatt also affirmed the position of the female as independent professional artist. It may be surprising, therefore, to learn that almost a century later, the American feminist activist group known as the Guerrilla Girls (see later discussion) felt it necessary to launch a scathing attack on the art world for its continuing subjugation of women, and on some of New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s best-loved male artists. The nineteenth-century French Neo-classical painter Jean-Au-guste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) came under their satirical spotlight, for example.

Figure 6.7 | Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Loge, 1874, oil on canvas, 80 × 63 cm, London, Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery.

Source: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Library.

Figure 6.8 | Mary Cassatt, In the Loge, 1878, oil on canvas, 81.28 × 66.04 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Hayden Collection – Charles Henry Hayden Fund 10.35.

Source: Photograph © 2015 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved / Bridgeman Images.

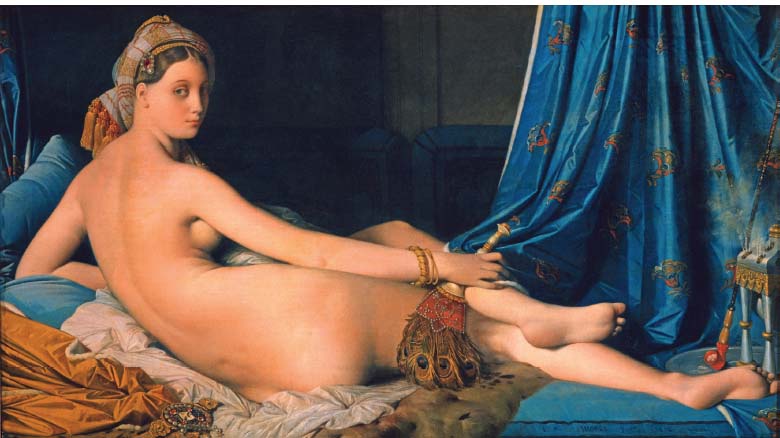

Figure 6.9 | Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, oil on canvas, 91 × 162 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Source: © 2015. A. Dagli.Orti / Scala, Florence.

Figure 6.10 | Guerrilla Girls, Untitled or Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?, 1989 (from the series ‘Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: The First Five Years’, 1985–1990).

Source: Copyright © Guerrilla Girls / Courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com.

Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque, 1814, epitomises the distortions imposed on women’s bodies by the imposition of idealised ‘perfection’. Ingres’ women are deeply sensuous to the point of being anatomically incorrect. The woman in this painting appears to have three extra vertebrae, which elongate the spine and help her back seem even more sinuous, so enhancing her unblemished appearance. Arguably we see a similar technique in today’s airbrushed models, whose legs are lengthened and skin made to appear flawless to help sell films, cosmetics and magazines. (Most recently, however, male models are as much a victim of the idealisation treatment as female models; consumerism does not appear to discriminate as easily anymore.)

The Guerrilla Girls, in their Untitled from the series ‘Guerrilla Girls Talk Back: The First Five Years’, parody Ingres’ odalisque model and ridicule the objectification of women and women’s constructed role as passive muse rather than active artist.

The semiotics associated with sexual desirability is frequently used in today’s media. For example, in the advertising campaign for a Dolce and Gabbana fragrance, ‘The One’, the mise-en-scène, the knowing flick of the hair (in place of Ingres’ caressing feather), and the invitation to the male voyeur, are as potent as ever.

In The Turkish Bath, 1862, also by Ingres, the artist presents, whether intentionally or not, the ultimate male fantasy in this pile-up of fleshy, wanton females. This tondo adds to the feeling of glimpsing into a secret cavern of Oriental eroticism as though peeping through an illicit keyhole. The scene is intended to appear as set in a Middle Eastern country, and its titillating subject is made just about acceptable by virtue of its ‘otherness’. Ingres’ work is a fruitful subject for examination in terms of gender and ethnicity.

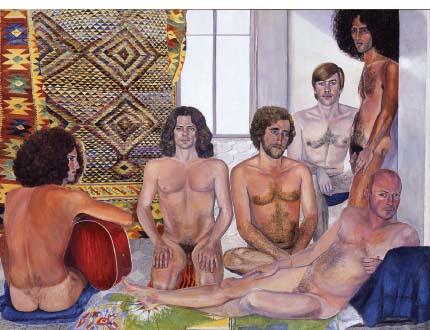

Subverting the ‘male gaze’

The Turkish Bath, 1973, by the artist Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010) playfully mimics Ingres’ objectifying viewpoint, but here Sleigh positions male models languidly, seductively and nakedly in front of the viewer. She also makes a decorative feature out of body hair and tan lines. The mise-en-scène is a little less alluring than in Ingres’ painting and the men look more confrontationally at us. The image makes us question why this should seem more surprising than Ingres’ representation. Indeed, the very fact of the production of such a work may seem to us indicative of changing power relations in society as well as evidence of the rising numbers of women able to train and achieve success as artists. Contemporary American feminist writer Whitney Chadwick states:

Sylvia Sleigh’s male nudes combine portrait genre with the nude as a representational type. In Philip Golub Reclining (1971), The Turkish Bath (1973), and other paintings of the 1970s, Sleigh reverses a history in which men contemplate the naked bodies of women. (Chadwick, Women, Art and Society, p. 370)

Sleigh replicated the objectifying gaze, only reversing its gender roles, but contemporary British artist Jenny Saville (born 1970, discussed in Chapter 1 and Chapter 5) challenges and repels objectifying spectatorship with her monumental female nudes made so fleshy they loom over the spectator.

Figure 6.11 | Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath, 1862, oil on canvas, 108 × 108 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Source: © 2015. Photo Scala, Florence.

Figure 6.12 | Sylvia Sleigh, The Turkish Bath, 1973, oil on canvas, 193 × 259.1 × 5.1 cm (framed: 203.2 × 266.7 × 12.7 cm), The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago; purchased by Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions.

Source: Photograph 62014 courtesy of The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago.

Figure 6.13 | Jenny Saville, Hybrid, 1997, oil on canvas, 274.3 × 213.4 cm.

Source: Photo courtesy Gagosian Gallery. © Jenny Saville. All rights reserved, DACS 2015.

In utter contrast to the idealised nudes painstakingly depicted by Ingres, Saville presents us with another entirely modern take on the female nude. Saville’s Branded, 1992, was examined as an example of self-portraiture in Chapter 1 and we may remember her painterly assault on society’s view of fat women as ‘folk devils’. Hybrid, 1997, is so wrong, it’s right: it takes the ‘constructed’ female body, mythologised over the centuries and, by way of patchwork flesh, shows the very act of that construction as unnatural and pernicious. Saville removes us from mythology into the real world and forces us to confront the consequences of desiring perfection. It would appear that, from Saville’s perspective, women diet, exercise and learn to hate themselves to the point where they become their own enemy. The implication is that women are supposed to cut themselves into pieces under the surgeon’s knife to be reborn beautiful. In the same way that Saville confronted us with prejudice towards fat people in Branded, she presents us with the damaging unnaturalness of perfection in Hybrid. Can Saville’s Hybrid be viewed as a reaction to eighteenth-century artist and writer Sir Joshua Reynolds’ lectures on what makes a body beautiful in art?

Women persecute themselves with a desire to retain adolescent figures … Plastic surgeons use computers to create the perfect face, but it will achieve such blandness. What would beauty be, if everyone looked the same?

(Jenny Saville quoted in Kent, Shark Infested Waters: The Saatchi Collection of British Art in the 90s, pp. 83–84)

The ‘masculine’ prototype, the sensuous male and gender duality

Representations of the male form have tended to be powerful, erect and noble. Look, for example, at Michelangelo’s (originally Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, 1475–1564) High Renaissance sculpture David, 1501, which served for generations as an emblem of ideal masculinity: gracefully poised, powerfully muscled and victorious in combat. Of course this stereotype can be just as imprisoning for men as female stereotypes can be for women. Accordingly, representations of men in art often display men as possessing strength; however, such power is threatened by the pressure of keeping the stereotype intact and repressing elements perceived as weak. To an extent, this sometimes seems beyond the conscious control of the artist, just as it may be beyond the capacity of an individual to live up to the gender-ideal of their time.

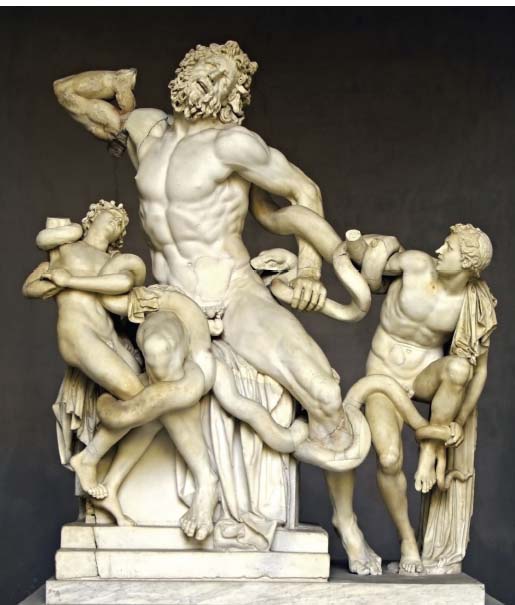

The central figure of the Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön, appears to demonstrate a very early sense of ‘masculinity’ – a rippling musculature that has, arguably, been matched but never surpassed in stone.

In this marble masterpiece, the priest Laocoön is encoiled by a deadly serpent as punishment for warning the Trojans against accepting a wooden horse as a gift from the Greeks. He is flanked by his sons and together they fight their certain deaths in vain. In wrestling the coiling monster, Laocoön’s body twists in stunning contrapposto and every sinewy tendon and muscle-bound limb is accentuated in the throes of battle. The central protagonist becomes an archetypal powerhouse of ‘masculinity’; and yet, maybe what the statue really shows us is the figures’ own struggle to maintain an impossible ideal of strength and mastery. What might a psychoanalyst say about the gender-symbolic significance of the serpent? You may like to compare Laocoön with its ‘feminine’ Hellenistic counterpart the Venus de Milo, third to first centuries bce.

Figure 6.14 | Laocoön, group from the Hellenistic period, first century bce, marble, height 208 cm.

Source: © Zaharov / iStockphoto.

Figure 6.15 | Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze, c.1876/1877, bronze, height 182.9 cm, Paris, Musée Rodin.

Source: Musée Rodin, Paris, France / Photo © AISA / Bridgeman Images.

The relationship between gender and art is too often over-simplified and categorisation can be unhelpful and misleading. The figure in The Age of Bronze, c.1876/1877 by Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), seems to melt rhythmically and gracefully from the top of his odalisque-like elbow to his toe, and he is poised on one foot with his hips tilted out in a typical posture of physical display. The patinated surface of the statue appears wet with a sensuous sheen and this male figure, while standing erect with a wealth of impressive musculature on show, is effeminate to the point that he seems to confront both ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ stereotypes.

In what sense can the sculptures described above be discussed in terms of gender? A rigid classification is sometimes impossible, although some works do function primarily in this way. Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, 1793, by Antonio Canova (1757–1822) is a notable example. Ask yourself how the sculptor has represented the figures. They are certainly graceful and captured in a moment of loving embrace, but they are also very sensual: the male figure touches the female figure’s breast, their eyes meet and an imminent kiss becomes our focus within their framing arms.

In terms of its gendered representation, Psyche is horizontal, languid, passive and bare-breasted; Cupid is vertical and active, controlling her head with his hand. He has the power of flight – notice the way he pivots on his feet, wings still not yet rested.

Women have appeared in the role of seductress, object of beauty and victim in equal measure throughout art history. While Canova’s eighteenth-century marble exemplifies a reverent and masterful Neo-classical beauty, in which woman appears as the ideal object of romantic love, Alberto Giacometti’s twentieth-century bronze, Woman with Her Throat Cut, depicts the female figure as victim of physical, and possibly sexual, violence.

Who is victimised here?

In Woman with Her Throat Cut, 1932, Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) depicts a violated and murdered mutant figure that is, arguably, denied identity other than as an object of desire and abuse. Part female, part insect, her fragile legs are unnervingly splayed, and her torso appears torn open to reveal the curvature of her abdomen; two tiny breasts between twig-like arms enable us to identify her sex. Spoon-shaped hands anchor her helplessly to the floor. An arched and extended trachea terminates with a tiny head and an open mouth that belies her silence; she is anonymous and without voice. Typically displayed on the floor without a plinth, the sculpture suggests an invitation to walk over the hybrid figure. We look down on the work, its battered surface capturing the light as we watch her convulse in the throes of death and suffering.

Figure 6.16 | Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, 1793, marble sculpture, height 155 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Source: The Art Archive / Musée du Louvre Paris / Gianni Dagli Orti.

This work could be understood as representing a hideously misogynistic depiction of the female nude, but this reading may be too simplistic. Her torment is unnerving enough to subvert the voyeurism attached to the history of the nude. The themes of sex and violence surface more immediately than issues of gender; or do they? As the gallery label at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, puts it:

Figure 6.17 | Alberto Giacometti, Woman with Her Throat Cut, 1932, bronze (cast 1949), 20.3 × 87.6 × 63.5 cm, New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Purchase. Acc. n.: 696.1949. Source: © 2015. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence / ©The Estate of Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Giacometti, Paris and ADAGP, Paris), licensed in the UK by ACS and DACS, London 2015.

Giacometti originally intended Woman with Her Throat Cut to rest directly on the floor, part of the ‘real’ world, distanced from the lofty realm of art. A hybrid animal, insect, and human, the female figure’s body appears to be simultaneously in the throes of sexual ecstasy and in the spasms of death – embodying the phrase petite mort (little death), a French term for orgasm. The sexual drama and violence in this work is a powerfully discomfiting example of the misogynistic imagery frequently present in Surrealism. (Exhibition label ‘The Erotic Object: Surrealist Sculpture from the Collection’, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2009–2010)

Figure 6.18 | Louise Bourgeois, The Destruction of the Father, 1974, latex, plaster, wood, fabric and red lighting, 237.8 × 362.3 × 248.6 cm.

Source: Photo: Rafael Lobato, ©The Easton Foundation /VAGA, New York / DACS, London 2015.

You may recall the grisly murder scene Judith Slaying Holofernes, painted by the female Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, c.1593–1652 (examined previously in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4). Gentileschi, herself the victim of torture by the authorities following her seduction by her tutor, sought revenge in the only way she could – painting the brutal decapitation of Judith’s enemy – Holofernes.

Figure 6.19 | Louise Bourgeois, Maman, 1999, bronze, stainless steel and marble, 927.1 × 891.5 × 1023.6 cm, Paris, Jardin des Tuileries, 2008.

Source: Photo: Georges Meguerditchian, © The Easton Foundation /VAGA, New York / DACS, London 2015.

The recurring role of woman as sexual victim throughout the centuries found a particularly critical voice in the work of contemporary feminist artist Jenny Holzer, who brought the idea of female vulnerability home with her series of ‘Truisms’ (a statement that is obviously true), particularly the work Murder has its Sexual Side, 1993/4.

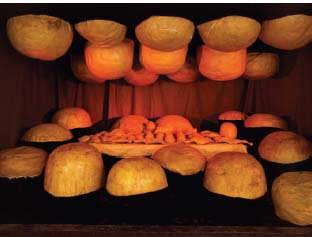

The theme of violence, and often sexualised violence against women, has been explored by numerous other male and female artists. However, the late French artist Louise Bourgeois contributes a reversal of the usual order of things in her seminal work The Destruction of the Father, 1974.

The revelation that Bourgeois’ philandering father had been having a long affair with her governess had a lasting impact on her and her subsequent work. The Destruction of the Father is usually interpreted as a confessional and Freudian exploration of her father’s dominance over her mother and his offspring; the womb-like installation in mixed-media glows with the expectant consumption of the dominating father. The children, featured as abstract blobs, murder their father in an unthinkably cannibalistic crime. Bourgeois described the ‘event’:

He is unbearably dominating although probably he does not realize it himself. A kind of resentment grows and one day my brother and I decided, ‘the time has come!’ We grabbed him, laid him on the table and with our knives dissected him. We took him apart and dismembered him, we cut off his penis. And he became food. We ate him up … he was liquidated the same way he liquidated the children. (Louise Bourgeois quoted in Conn, ‘Delicate Strength’)

Bourgeois’ oeuvre tends to be characterised by issues relating to parenthood, the male form and childhood. Maman, 1999, is a monumental sculpture of a giant female spider and Bourgeois has said it represents the power, protection and strength she associates with the figure of the mother:

The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver. My family was in the business of tapestry restoration, and my mother was in charge of the workshop. Like spiders, my mother was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother. (Tate Gallery, ‘Tate Acquires Louise Bourgeois’s Giant Spider, Maman’)

Bourgeois broke down masculine barriers in the art world with her mastery of the ‘masculine’ medium of sculpture, and subverted typical representations of the victimisation of the female. American artist Judy Chicago caused similar controversy in the male-dominated museum world of the 1970s with her famously explicit form of female iconography. At this time in Britain and the United States, a consciously feminist art was emerging and gaining support from a range of feminist publications that included Spare Rib in Britain and The Feminist Art Journal in the United States.

The celebration of woman’s work

The feminist installation The Dinner Party, 1979, by Judy Chicago (born 1939) was first exhibited in 1979 and comprises 39 multi-media place settings (13 on each side of an equilateral triangle). Its triangular formation references an ancient symbol of femininity, while its equilateral nature represents the ideal of gender equality. Each elaborately decorated place setting celebrates an important woman in history and place settings include sensuously shiny dinner plates shaped to evoke the form and delicacy of female genitalia. Chicago describes these open, petal-like ceramics as a central core, my vagina, that which made me a woman (Chadwick, Women, Art and Society, p. 358).

Figure 6.20 | Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1979, mixed media, 1463 × 1463 cm, New York, NY, USA, Brooklyn Museum. Source: Photo: © Donald Woodman, courtesy of Judy Chicago / Art Resource, NY / © Judy Chicago. ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015.

Patriarchy, according to feminists, has also been responsible for the separation of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. Typically, craft work has been considered ‘low’, ‘feminine’ and devalued in comparison to the so-called ‘high’ arts of painting and sculpture, which for centuries restricted training to men and so have been male-dominated. Chicago, and other feminist artists like her, resurrected craft skills and elevated ‘low’ – and by extension female – art to the status of ‘high’ art by exhibiting it in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In The Dinner Party, decorative needlework records the names of honoured women, who include artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo, and the writer Virginia Woolf. Butterflies are scattered in various stages of evolution (from larva to fully winged) as symbols of emancipation. Two decades later, contemporary British artist Tracey Emin (born 1963) drew on needlework skills (although her work is deliberately rough and ready in appearance) to create her infamous tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963– 1995, 1995. Unfortunately, this work was destroyed in a warehouse fire in 2004.

Figure 6.21 | Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1979, detail, Virginia Woolf place setting, mixed media, 1463 × 1463 cm, New York, NY, USA, Brooklyn Museum.

Source: Photo: © Donald Woodman, courtesy of Judy Chicago / Art Resource, NY /© Judy Chicago. ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015.

Figure 6.22 | Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, 1995, fabric appliqué, mattress, light.

Source: ©Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2015. Image courtesy White Cube.

As the title suggests, Emin embellished this tent – a shop-bought readymade – with the names of everyone she had ever slept with (meaning this term in the sense of sleeping, not sexual relations). The names include Emin’s grandmother as well as the words ‘FOETUS I’ and ‘FOETUS II’, referring to two lost pregnancies. This embellished object subverts ‘high’ art once again through its use of craft techniques – a historically relegated and ‘feminine’ practice. Emin’s tent stands unapologetically as a monument both to the artist’s subjective feelings and to the elevation of the craft of appliqué in a contemporary canonical context. Emin’s social and cultural status as an artist is discussed in Chapter 5.

Gender inequality is not simply found in relation to the artist, subject or technique of the work of art; it is also to be found in an under-representation, or complete omission, of women’s art work from galleries, collections, exhibitions and art history books. The latter was the subject of Linda Nochlin’s essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ In this article, Nochlin explored why the status of artistic ‘greatness’ has been reserved for male artists such as Michelangelo and argues that the social expectations were historically against women pursuing art as a career, and so there were restrictions on women’s art education and ability to exhibit and sell art works. These factors precluded the emergence of great women artists.

Gender issues in painting and sculpture are widely discussed, and an enormous body of literature exists to provide the reader with myriad related perspectives. However, the examination of gender and architecture is a path less worn, although no less interesting in scope.

Gender and the built environment

According to architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, [t]he politics of space are always sexual (Colomina, ‘Introduction’). The following discussion seeks to examine architecture in relation to gender difference and so to navigate a complicated area of evolving discussion.

At the beginning of this chapter, Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait was discussed in association with ideas regarding the association of women with private domestic spaces and the association of men with outdoor, public spaces. These associations arose because of the different kinds of work done by men and women and the different social roles they were supposed to take historically. In his essay ‘The Housing of Gender’, architectural historian Mark Wigley identifies women’s supposed propensity to immorality if granted freedom outside the home as a belief dating back to ancient Greece. He argues that the consequent effort to restrain women inside the home has had a lasting legacy in architecture, through the construction not only of architectural discourse but also of physical architectural spaces: Unable to control herself, she must be controlled by being bounded (Wigley, ‘Untitled: The Housing of Gender’, p. 335).

The active production of gender distinctions can be found at every level of architectural discourse: in its ritual of legitimation, hiring practices, classification systems, lecture techniques, publicity images, canon formation, division of labor, bibliographies, design conventions, legal codes, salary structures, publishing practices, language, professional ethics, editing protocols, project credits etc.

(Wigley, ‘Untitled: The Housing of Gender’, p. 329)

Architecture, in this sense, has been used historically to help regulate the social behaviour of men and women, and in particular to help reinforce the idea that a woman’s place is in the home.

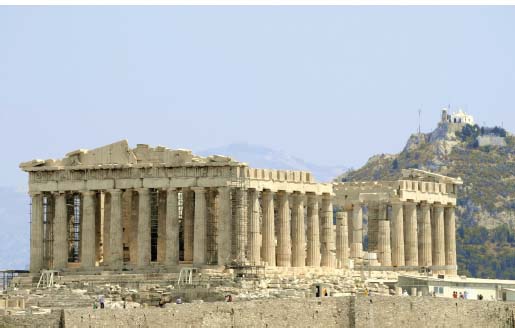

Gender symbolism has been attached to particular formal features of architecture since Antiquity; the ancient Greeks developed three Orders: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian, and the former two have been personified as ‘male’ and ‘female’, respectively (architectural Orders are most easily distinguished by their capitals). Roman writer, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio on the character of the Doric and Ionic Orders, stated: Thus two orders were invented, one of a masculine character, without ornament, the other bearing a character which resembled the delicacy, ornament, and proportion of a female (Vitruvius, De Architectura, Book IV, Chapter 1:7).

The Parthenon, the Temple of Athena Parthenos, in Athens is considered to be the finest example of the Doric Order ever built. The Doric Order, named after the Dorians, an ethnic Greek tribe, was thought to display stereotypically ‘masculine’ attributes on account of its proportions: larger diameter columns with a plain, strong design. The Doric Order also carried the heaviest entablature and became a metaphor for power and strength. While the Parthenon is built primarily in the Doric Order, its inner colonnade comprises Ionic columns supporting a continuous frieze – an ambivalent hybrid that its architect Iktinos had made his own. Despite its primary masculinity, the Parthenon was built to house the goddess of wisdom and war, Athena. However, the mythological story of Athena brings a level of complexity to our analysis of her as the ‘feminine’ aspect of the ‘masculine’ Parthenon. Born not from her mother but from her father’s head, Athena appears from the very first instance in full armour and remains an unmarried virgin and goddess of war, no less.

Figure 6.23 | Iktinos and Kallikrates, The Parthenon Temple, 447–438 bce.

Source: © krechet / iStockphoto.

Compare the Doric Order of the Parthenon with the Ionic Order of the Temple of Athena Nike in Athens, late fifth century bce. What are their technical differences? How do their differing proportions and decorative treatments support an analysis in terms of their ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’? Since Antiquity, the Golden Section (discussed in Chapter 3) has been regarded as the perfect proportion. Expressed as, it is also known as the ‘divine proportion’ and is found in nature and mathematics and used in art and architecture. The Golden Section is a ratio of 1:1.618, regarded as the most ideal proportion not just aesthetically but also because it occurs in nature, in such things as seed spirals in sunflowers and shells. In seeking the ideal, artists and architects applied geometrical proportions, including the Golden Section, to the human body.

Figure 6.24 | Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, 1490, pen and ink, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia.

Source: © Dennis Hallinan /Alamy.

Leonardo da Vinci based his drawing Vitruvian Man on some tentative correlations of ideal human proportions with geometry in Book III of the treatise On Architecture (De Architectura) by the ancient Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. According to architectural theorist Diane Agrest, the patriarchal Renaissance discourse that symbolically excluded women at professional and built level was considered normative after a while:

Architecture in the Renaissance establishes a system of rules that is the basis of Western architecture. The texts of the Renaissance, which in turn read the classic texts from Vitruvius, develop a logocentric and anthropomorphic discourse establishing the male body at the center of the unconscious of architectural rules and configurations. The body is inscribed in the system of architecture as a male body replacing the female body. (Agrest, ‘Architecture from Without: Body, Logic and Sex’, p. 359)

In the mid-twentieth century, German architect and dominant figure in skyscraper design Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), created strictly functional, non-decorative, glass-walled structures that punctuated the American skyline with a ‘masculine’ authority and scale. The Miesian prototype answered the need for corporate office spaces and delivered the acme of the modernist aesthetic in the process. Arguably, the vertical force, competing height and sleekly engineered façades sat comfortably in a city. How do these vertical forms symbolise male power and authority?

The Seagram Building, 1958, was designed by Mies van der Rohe in collaboration with the American architect Philip Johnson. At the time of its construction, it helped to establish the lexicon of skyscraper design and chimed with the disciplined and commercial demands of New York City. In what sense is the Seagram Building gendered? What formal characteristics are you identifying to justify your response?

The twentieth-century skyscraper, a pinnacle of patriarchal symbology, is rooted in the masculine mystique of the big, erect, the forceful – the full balloon of the inflated masculine ego.

(Weisman, ‘Prologue’, p. 1)

According to architectural theorist and writer Jane Rendell, the male-dominated profession of architecture affects women in a number of different ways:

Women’s exclusion from the architectural profession and education is not only a historical problem but also one critical to the role of women architects practising today. For example, in the United Kingdom, although many women start architectural courses – an average of 27 per cent of all architectural students are women – only 9 per cent of women complete their studies and practise architecture. In the profession, although there has been an increase in the number of women registered as architects, from 5 per cent in 1975 to 11 per cent in 1997, the figure still shows that only one in ten of practicing architects is female. (Rendell in Rendell, Penner and Borden, Gender Space Architecture: An Interdiscipli-nary Introduction, p. 228)

Women may have been excluded from practising architecture historically, but recently some female architects have been responsible for creating some of the world’s most famous buildings. Amanda Levete collaborated with her husband Jan Kaplický to create the Media Centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground, examined in Chapter 4. Award-winning architect Jane Drew triumphed in a male-dominated profession to design and co-design numerous buildings all around the world, including ones in Milton Keynes for that bastion of inclusive learning the Open University. In 2004, Zaha Hadid became the first female in the world to win the Pritzker Architectural Prize – the profession’s highest award – and has most recently received tremendous media attention in relation to her Al-Wakrah Stadium in Qatar, on account of it looking far too female in form. What do you think?

Figure 6.25 | Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, Seagram Building, New York, 1958.

Source: © Philip Scalia / Alamy.

Architect Barbara Kuit worked with Mark Hemel to create the Canton Tower, Guangzhou, China, 2009 – the world’s tallest TV tower – and designed a building so female in form it’s been dubbed the ‘Supermodel’: the structure’s two ellipses tighten in the middle to form ‘her’ waist. How does her nipped-in form defy the ‘masculine’ prototype for skyscraper functionality?

Another building whose idiosyncratic form confers gender stereotypes is that created by Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry (born 1929) and Croatian-born architect Vlado Milunić (born 1941) in Prague for the giant insurance company Nationale-Nederlanden. The architects eschewed Canadian, Czech and Dutch identities to create a structure for which there was no precedent in Prague’s historic centre. Known officially as the Netherlands National Building, and playfully as the ‘Fred and Ginger’ building – after twentieth-century dancers Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers – the structure’s form lends itself readily to a discussion of gender and architecture, just as much as it serves to defy nationalism. The left-hand structure of this building mimics the female form; its glass sheathing is fragile, and its dress-like frame appears delicate and corseted. Together, these structures combine to appear dancing and highly gendered. It also has a dancing fenestration: geometric windows on rhythmically decorated walls.

Gehry and Milunić created a Deconstructivist icon for Prague, debunking modernist aesthetics and pulling apart old formulae. Their postmodern caricaturing smacks of an ‘anything goes’ Zeitgeist and puts any discussion of gender identity into an uncomfortable state of flux. Similarly, the Netherlands National Building also has an interesting and unexpected contribution to make to the theme of nationality. Former Soviet occupation and dominance necessitated a need to reassert Czech architecture in order to heal old wounds and Gehry’s and Milunić’s creation was viewed by some of its critics as more American and less Czech than had been hoped for. Academic writers Sibelan Forrester, Magdalena Zaborowska and Elena Gapova stated:

In this context, as the most visible and widely publicised contemporary building in Prague, the Netherlands National Building will continue to represent an important moment in the ongoing debate over Prague’s architectural future. For many, the transposition of the signature style of an important American [sic] architect into the centre of Prague connotes Western cultural imperialism. However, for many Czechs, the building also symbolises renewed cultural and economic links to the West. While an American critic may see another prestigious sculptural building that functions primarily as [a] monument to itself and its maker, many Czechs see a new symbol of creativity and freedom regained. (Forrester, Zaborowska and Gapova, Over the Wall/After the Fall: Post-Communist Cultures Through an East– West Gaze, p. 123)

It seems that Frank Gehry himself was well aware of the nationalist associations his building could elicit. His co-architect, Vlado Milunić, was asked in 2003: In the beginning it was more commonly known as the Fred and Ginger Building, now everyone seems to call it the Dancing Building – did the Fred and Ginger name just disappear? To which he answered: That was Frank’s idea but then he was afraid to import American Hollywood kitsch to Prague (Willoughby, ‘Architect Recalls Genesis of Dancing Building as Coffee Table Book Published’).

Figure 6.26 | Frank Gehry, and Vlado Milunic Netherlands National Building or ‘Dancing House’, Prague, 1996.

Source: © age fotostock / Alamy.

Figure 6.27 | Frank Gehry, and Vlado Milunic Netherlands National Building, Prague, 1996, detail of dancing window.

Source: © Andrea Visconti /Shutterstock.

Nationality

So much of art history is viewed through the lenses of national and geographical difference and the history of nations competing for dominance. Trends in international trading and the recent phenomenon of globalisation may have led to the erosion of distinct national identities. Despite these changes, nations across the globe have erected monuments that assert their national supremacy to the world.

Emblems and monuments to national identity

Famous for its depiction of the people’s revolution against the monarch Charles X, Liberty Leading the People, 1830, by Eugène Delacroix (1798– 1863) is a useful example to study in relation to the topic of ‘nationality’. Liberty, the embodiment of the fight for freedom, strides towards us, the tricolour flag (ultimate emblem of French nationality) held high and emphatically on the central vertical axis. There had been fighting in the capital since the previous day and the citizens of Paris and the king’s troops had formed ranks on opposite sites. Barricades had been erected. Shots had been fired. People had been killed. Early that morning, the senior commander of the royal troops informed the king: This is no riot. This is a revolution (Hagen and Hagen, What Great Paintings Say: From the Bayeux Tapestry to Diego Rivera, p. 567). The citizens of Paris united, and the 27th, 28th and 29th of July 1830 were ‘Three Glorious Days’ of revolution (the second major revolution after the French Revolution of 1789). Insurgents from every class revolted against the policies of Charles X. Among the king’s decrees was censorship of the press, and the citizens of Paris fought hardest in defence of this freedom. The insurgents were triumphant and the king was forced to abdicate.

Liberty Leading the People may allude conveniently to nationality, but the centrality of its female warrior has also attracted feminist analysis. Linda Nochlin concedes that Delacroix’s Liberty is not a conciliatory peacemaker but a bellicose leader; however, she also notes that Liberty’s active and emphatic lead is only by virtue of the fact that she is neither a historical personage nor a contemporary member of the crowd she leads but, rather, an allegorical figure (Nochlin, Representing Women, p. 49).25 Delacroix wrote to his brother, If I haven’t lived for my country, at least I shall paint for it! (Hagen and Hagen, What Great Paintings Say: From the Bayeux Tapestry to Diego Rivera, p. 569).

Figure 6.28 | Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (Allegory of the July Revolution 1830, with self-portrait), 1830, oil on canvas, 360 × 225 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Source: akg-images.

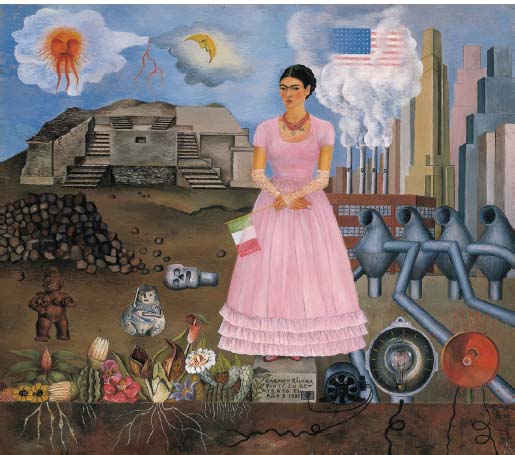

In the same way that the revolution of 1830 inspired Delacroix to paint, the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920 inspired the work of the fervently nationalistic Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Following the revolution, and after many years of colonialism, Mexico fostered a proud national culture pertaining to all things Mexican, known as Mexicanidad. No one celebrated Mexicanidad more than Mexico’s most famous female artist, Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). Such was Kahlo’s sense of national pride that she changed her birth date to 1910 (she was born in 1907) to coincide with the Mexican Revolution (see 6.2 Let’s connect the themes: historical perspectives), thus realigning herself more fully with its cause. Kahlo also developed what could be described as a national style: naive and folk-like with references to popular culture, but also reminiscent of traditional Catholic colonial Mexican ex-voto and retablos paintings, some alluding to ancient gods, native flora and fauna, Mexican costume and produce.

Figure 6.29 | Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States, 1932, oil on canvas, Private Collection.

Source: Private Collection / Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images / © 2015. Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / DACS.

Figure 6.30 | Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan. This site is believed to date from the second century bce and its position as central to ancient Mexico is revered.

© Lazcanini / iStockphoto.

Kahlo conveyed her Mexican nationality throughout her oeuvre (her painting Viva La Vida, examined as an example of still life in Chapter 1, is a notable example), but Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States, 1932, is the most explicit indication of how she felt about her ancient homeland, which is on the left of the painting, and the comparatively grey and industrialised United States, on the right. Kahlo stands in the middle of the composition on the fault-line of their polarised divide. She is holding the Mexican flag in her left hand and shifting her body on its pedestal towards home – an outward indication of nationalistic loyalty. This painting is political: it represents Kahlo’s post-revolutionary, left-wing national identity. She paints the United States as the bastion of capitalism and Mexico as a cultural heartland rejuvenated by the post-revolution transformation of the nation.

Apart from the painting’s title and composition, Kahlo expresses her affiliation with Mexico in a number of other ways: dressed in an indigenous Tehuana dress with pre-Columbian beads around her neck, the artist stands over remnants of the ancient Aztec culture she often referenced in her work. In the left-hand foreground, vibrant colours and lush native flowers spring from the fertile soil, which nurtures (solid roots have taken hold) regeneration. On the right, monochromatic factory parts feed from electric cables, which appear lifeless in comparison (although they represent the air-conditioning, heat and light Americans enjoyed and Mexicans aimed to achieve). The mechanised production in the background spells out ‘FORD’, ex-voto style, perhaps as though this brand-name were a kind of industrial god that supports the Stars and Stripes above it. White vertical puffs of polluted air belch out from Ford’s pipes and find their opposite – or perhaps their parallel – in the horizontal clouds on the left that drift above an ancient ruined Aztec temple. Beneath the temple are fertility dolls and a skull to remind us of the cycle of life, in contrast to the anthropomorphic ducts – a continuing duality that pervades the entire canvas. Does the painting represent the superiority of one culture over another, or their equivalence?

Does the fact that Kahlo was a woman mean that critics automatically assume she privileges ‘nature’ over technology in her work?

Kahlo’s pride in her nation was expressed in small-scale works that took decades to reach a worldwide audience. Expressions of nationality in architecture tend to make their impact more instantaneously, however.

Alexandre Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923) was a French structural engineer who founded his own engineering office in 1866 and designed and built bridges all over Europe. He is best known, however, as the architect of the world-famous Eiffel Tower, 1887–1889, which was built for the 1889 ‘Universal Exposition’ in Paris, France. (see Figure 6.31)

The Eiffel Tower took centre stage at the ‘Exposition Universelle’ in 1889 to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution, and drew unprecedented numbers of people to the capital. The tower is now recognised as a national symbol of France the world over. At 301 metres high, it was the tallest structure in the world at the time of its completion.

Figure 6.31 | Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, The Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1887–1889, wrought iron, height 301 m.

Source: © carterdayne / iStockphoto.

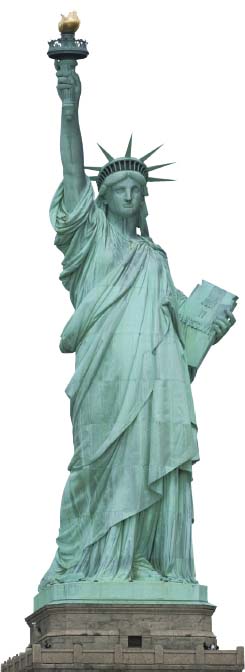

Figure 6.32 | Frédéric Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, 1886, copper.

Source: © Nikada / iStockphoto.

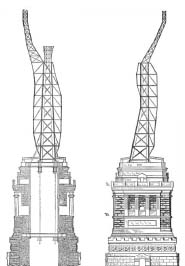

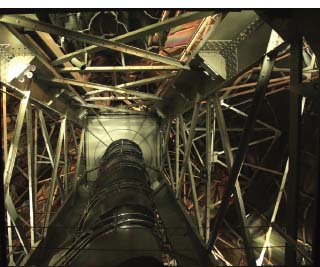

Across the Atlantic, the monumental and equally iconic Statue of Liberty took up residence on Liberty Island at the entrance to New York Harbour in 1886, a gift from France to its friend and fellow Republican nation, the United States of America. Liberty was born from the collaborative efforts of the sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi (1834–1904) and the engineer Eiffel. Eiffel designed the interior armature for the statue, which became a universal symbol of freedom as well as a national emblem of the United States. Immigration to the United States was unparalleled during the second half of the nineteenth century, and the Statue of Liberty was placed so as to be the first figure new immigrants would see as they arrived by sea, extolling the virtues of a free country to its foreign arrivals.

Figure 6.33 | Frédéric Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, drawing of the internal armature designed by Gustave Eiffel, from Scientific American, 13 June 1885.

Source: Scientific American.

Figure 6.34 | Frédéric Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, internal armature by Gustave Eiffel.

Source: © debstheleo / iStockphoto.

Including its base, the statue stands a colossal 93 metres high, the classical goddess Liberty is represented here as a colossal sculpture holding aloft a torch in her right hand and a tablet that evokes the law in her left. The tablet is inscribed with the date of the American Declaration of Independence: JULY IV MDCCLXXVI (4 July 1776). The broken chain at her feet and the torch in her hand represent freedom and enlightenment, respectively. The Statue of Liberty was classified as a World Heritage Site in 1984 on the basis of a number of criteria, of which the following is an example:

Criterion VI. The symbolic value of the Statue of Liberty lies in two basic factors. It was presented by France with the intention of affirming the historical alliance between the two nations. It was financed by international subscription in recognition of the establishment of the principles of freedom and democracy by the U.S. Declaration of Independence, which the Statue holds in her left hand. The Statue also soon became and has endured as a symbol of the migration of people from many countries into the United States in the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. She endures as a highly potent symbol – inspiring contemplation, debate and protest – of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunity.(UNESCO, ‘Statue of Liberty’)

Such is the affinity between architecture and nationality that the establishing shot of many films uses landmark buildings, such as those examined here, to indicate the location (and country) of a particular scene; for example, Big Ben or the London Eye for London, the Eiffel Tower for Paris, the Sydney Opera House for Australia and the Statue of Liberty for New York.

The Opéra Garnier, 1861–1875, examined briefly in Chapter 4, was commissioned by Emperor Napoleon III as part of a monumental renovation of the city of Paris supervised by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. De-signed by Charles Garnier (1825–1898), and located at the top of the Avenue de l’Opéra, it was intended to be one of the capital’s most admired buildings and emblematic of the nation’s power, culture and influence. As well as being a theatre and a museum, it was a political statement of the authority of the Second Empire and remains a national monument. We examined Baron Haussmann’s renovation of central Paris in Chapter 4, and the opera house was a majestic sight in a wondrous new townscape.

Figure 6.35 | Charles Garnier, Opéra Garnier (Paris Opera), Paris, 1861–1875.

Source: © Rainbow / iStockphoto.

Opera houses have, for centuries, been associated with learnt cultures and powerful people. While Napoleon III’s Paris Opera provided an exemplary node in a nexus of the capital’s rebuilding, the Sydney Opera House became Australia’s most famous icon, despite being conceived and built by Danish architect Jǿrn Utzon (1918–2008). When awarding him the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour, in 2003, Thomas J. Pritzker, president of the Hyatt Foundation, said, Jǿrn Utzon has designed a remarkably beautiful building in Australia that has become a national symbol to the rest of the world (Pritzker Architecture Prize, ‘Danish Architect Jǿrn Utzon Becomes 2003 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate’).

This status is confirmed by the Australian government, which features it on its visa site with the accolade: as representative of Australia as the pyramids are of Egypt and the Colosseum of Rome (Visas Australia, ‘Sydney Opera House’).

The sail-like silhouette of its concrete roofs has become synonymous with the Australian nation itself and the material seems to belie the delicacy of its airborne form. The most striking and most photographed landmark in Australia, this unique building can be seen from miles around.

Figure 6.36 | Jǿrn Utzon, Sydney Opera House, 1973.

Source: © Kokkai Ng / iStockphoto.

Ethnicity

Figure 6.37 | John Nash, Royal Pavilion, Brighton, 1815–1822.

Source: © Lovattpics / iStockphoto.

Ethnicity is a term used to describe a person’s cultural heritage and/or racial identity, and this includes a shared language, food, style of dress and so on. To have an ethnic identity involves having a sense of pride and union with others of the same culture, which is why the term is inextricably linked with nationality. In fact, the following example relates to gender, nationality and ethnicity.

Through the eyes of an empire: hybridity and the mythologised ‘other’

The Royal Pavilion in Brighton provides an interesting example of the kind of cultural and ethnic hybridity that is often thought to characterise modern times. It is also a good example of a building that can stimulate discussion in terms of all three of the themes of this chapter: gender, nationality and ethnicity.

The Pavilion, a former royal residence commissioned by George IV when he was Prince Regent, is today owned by Brighton & Hove City Council and is open to the public. It began as a Neo-classical structure designed by Henry Holland and was transformed into its present, iconic Oriental style between 1815 and 1822 by architect John Nash (1752–1835). The Pavilion’s refashioning under Nash was achieved using an elaborate iron framework to which stone and stucco were attached. Its exterior has a distinctively Islamic style, although its interior is dominated by Chinese influences. Its iconic status can be attributed to its ethnic hybridity and its fantastically exotic punctuation of the skyline in an otherwise Regency-style environment.

George IV (1762–1830) was the king of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, Ireland and Hanover from 1820 until 1830. From his youth, he had been known for his extravagance and pleasure seeking. He loved Brighton and sought to ensure that his Royal Pavilion would become one of the world’s most talked-about buildings. As Jessica Rutherford notes in her book about the monarch, A Prince’s Passion, the king made such an impression on the seaside town of Brighton that the Sussex Weekly Advertiser, 24 April 1820, reported: the King is to this town what the sun is to our hemisphere – universal cheerfulness is presented when the rays of Royalty sparkle upon the picture of our local sociabilities and interests (Rutherford, A Prince’s Passion: The Life of the Royal Pavilion, p. 19).

The novelty of his idiosyncrasies soon waned, however, and many viewed his reign with contempt. In its long history, the Royal Pavilion, the king’s homage to empire, has been admired for its innovation and vilified for its mismatched vulgarity. Now a landmark, the Pavilion is affectionately regarded as one of the king’s greatest legacies to the nation.

As Britain’s empire grew in the East, the discourse of Orientalism became embedded in the West, and Nash, striving to satisfy the wishes of his patron, created an ethnic hybrid before the concept of cultural hybridisation had been coined. The Pavilion says more about the British nation’s enchantment with the East than about the East itself, however.

On the outside, the style would have been regarded as unmistakably exotic: Indian, Mogul and Oriental – a melting pot of its patron’s favourite flavours of the East. Richly decorated surfaces, horse-shoe arches and minarets are characteristically Islamic, while the Pavilion’s idiosyncratic crenellations, reminiscent of an iced cake, makes this structure quite a fantastical spectacle to behold in its setting of an English seaside town.

Gazing at the Pavilion, our eyes seldom find a place to rest; the façade appears to pop in and out and up and down with such regular irregularity that harmony is finally achieved. The central pavilion, crowned by a large onion dome with a band of eye-shaped windows around its exotic belly, is flanked on either side by striking minarets and subsidiary domes. Together, these fleshy rounded forms bulge voluptuously, perhaps like coded promises of the pleasures awaiting the visitor within.

Consider the composition of this building for a moment: the central pavilion is echoed by the side pavilions to form a tripartite composition overall. A repetition of rounded forms unifies the whole: the façade is predominantly curved, with rounded domes, double-bowed side pavilions, rounded central pavilion, circular motifs on subsidiary domes and so on. The ‘femininity’ of its organic bulges is relieved by the ‘masculine’ verticality of its towers.

The interior maintains its patron’s fascination with the East, but evokes China this time, via the decorative trend known as Chinoiserie. This is a term used to describe a European interpretation of Chinese art and decorations, producing an exotic stereotype. The whole building provides a theatrical viewing experience: mythical creatures bulge, leap and coil from every corner, and a riot of colour bedazzles in every detail. The furniture and stucco is gilded and even the cast-iron balustrade that guides you from one fantastical floor to the next has been given a bambooeffect treatment that suspends disbelief. Everything evokes the Orient or, more precisely, the Western perception of Eastern myth and its associated exoticism.

Figure 6.38 | John Nash, Royal Pavilion, Brighton, 1815–1822, detail of decorative parapets.

Source: © LanceB / iStockphoto.

Figure 6.39 | John Nash, Royal Pavilion, Brighton, 1815– 1822, elaborate dragon ceiling rose which supports the colossal chandelier in the centre of the Banqueting Room.

Source: © Angelo Hornak / Alamy.

The Royal Pavilion lends itself to an analysis in terms of both gender and ethnicity. The Pavilion’s ethnic hybridity is obvious, particularly when the entire building, inside and out is viewed as a whole; however, less obvious is its ‘femininity’, which, as the Pavilion’s keeper, David Beevers, confirmed, was largely attributable to its Chinese-inspired interior at the time:

Satirised and criticised, associated with female sensibility and rapacity, Chinoiserie allowed a welcome injection of the exotic into the classical mainstream. The number of surviving Chinese rooms in country houses testifies to its appeal in providing a sensual aesthetic based on irregularity, fantasy and ‘otherness’. (Beevers, Chinese Whispers: Chinoiserie in Britain 1650–1930, p. 24)

In her essay ‘What’s in a Chinese Room? Twentieth Century Chinoiserie, Modernity and Femininity’, Sarah Cheang points to John Galsworthy’s novel The White Monkey, 1924, from his series, The Forsyte Saga, as exemplifying Chinoiserie’s association with iniquitous morality and femininity in the British imagination. In this tale, Galsworthy presents the character of Fleur as an insatiable femme fatale, delectably fashionable and desirable, placed in the midst of a Chinese-style interior, complete with Pekingese dog. Fleur’s transformation from vixen to ‘dutiful’ mother is matched by the change in her taste in interiors, which becomes ‘Louis Quinze’, and her new dog a ‘Dandie Dinmont terrier’ (Beevers, Chinese Whispers: Chinoiserie in Britain 1650–1930, p. 76).

A sense of ‘Britishness’ so often associated with the monarchy and all its accompanying symbols was at the very least diluted by King George IV’s ethnically mixed Pavilion. However, the British fascination with the East had started long before the king’s reign. Portrait of Omai, c.1776, by British artist Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), provides an eighteenth-century insight into the West’s preoccupation with civilising the exotic ‘other’.

Figure 6.40 | Sir Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Omai, c.1776, oil on canvas.

Source: Courtesy of Sotheby’s Picture Library.

Omai was brought to England in 1774 from the Polynesian island of Huahine in a ship that took part in Captain Cook’s second voyage of discovery. He is presented by Reynolds in the garb and posture of an antique statue, as a ‘noble savage’ who has been ‘civilised’. During his two-year stay in Britain, Omai became a celebrity, a spectacle deeply revealing of the West’s attitude towards ‘other’ cultures, and this painting arguably tells us more about British imperialism than it does about Omai as a historical individual.

In her essay ‘Portrait of a Nation’, 2003, Patricia Fara stated: The latest scientific theories still assumed that white men lay at the summit of God’s creation, and Europeans regarded Pacific islanders as inferior primitives who were dirty, uncivilised and far closer to animals than themselves. But at the same time, they referred to the Pacific region as though it were a new Arcadia, and admired its inhabitants for living in an innocent, uncorrupted state, untainted by the depravity of modern civilisation and unburdened by the necessity of earning their living. (Fara, ‘Portrait of a Nation’)

Fara draws upon a duality of opinion that marked the period; polite society chose to focus on the romantic aspect of such transracial exchanges, while more enlightened critics drew attention to the exploitative and unnecessary expansion of empire in an elitist game of world dominance.

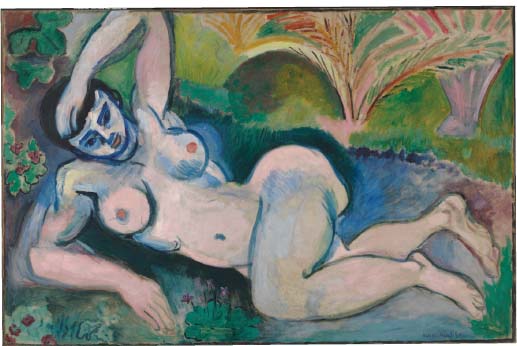

Some have suggested that the Arcadia, or idealised landscape, glimpsed in Reynolds’ background is typical of the way that people perceived ethnic ‘others’ as somehow identified with the realm of nature rather than the realm of reason, culture or science. We see similar Arcadian backgrounds in paintings by countless other artists, up to and including the twentieth century. Look at the work Blue Nude by French artist Henri Matisse (1869–1954), for example.

Blue Nude, 1907, may be interpreted as providing a male European’s imperialist perspective of an ethnic ‘other’. The system of beliefs at work both in Matisse’s painting and in its critical reception is sometimes known as ‘primitivism’: describing the racist prejudice that non-Western cultures are more ‘primitive’, meaning less developed, and perhaps closer to animal nature, than Western societies. This was a belief that permeated the language of European colonisers and the art that was produced in European societies during the colonial period. African, Oceanic (now known as Polynesian), Native American and other non-Western people and their cultures were all represented in this ‘primitivising’ way, indicating that they were considered to be inferior, albeit exotic and exciting, alternatives to the West. Matisse’s image presents us with a ‘primitive’ subject painted in a ‘primitive’ way: she reclines in an odalisque pose, her abundant breasts, accentuated buttock and shortened thighs con-Ethnicity Gender, Nationality and Ethnicity note her otherness. Naked and framed by exotic flora and fauna, she also signifies replenishment, an ‘oasis’ for the traveller, or perhaps a decorative and escapist vision of the artist’s personal Arcadia. The artist’s use of bold black outline and non-naturalistic colour defied the conventions of the traditional nude in Western painting and helped secure his status as leader of the artistic movement aptly labelled the Fauves (wild beasts). Despite this, or indeed because of this, the painting received damning reviews when it was first exhibited on account of its ugly deviation from academic standards. Many early twentieth-century European artists were inspired by so-called primitive art. According to Jonathan Harris,

[t]he production of these works was also dependent upon the imperialistic relation modern French artists had with the tribal societies and cultures of the Pacific islands and northern Africa that the western European nation-states had invaded, conquered, colonised, and exploited. (Harris, Art History: The Key Concepts, p. 252)

Thus, primitivism was adopted by avant-garde European artists as a device that helped them to reject the perceived corruption of the West and conventional academicism in art. The perceived ‘wildness’ of the subject matter and non-Western decorative styles and motifs helped European artists find the vivid and forceful means they needed to represent their rejection of tradition. In the bold and escapist vision of riotous colour and flattened form represented in Blue Nude, Matisse, perhaps unwittingly, both perpetuates colonial ideology and fuels the notion of the people of North Africa as ‘other’. At the same time, however, he produces a daring and innovative work by the standards of French painting at the time, and paved the way for future generations of artists to come.

Edward Said coined the term ‘Orientalism’ in his seminal book Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient, first published in 1978. The book examines the disparity between Said’s experience of being an Arab and the West’s mythologised representation of the Orient. Said asks why some people have preconceptions about the East, even though they may never have been there themselves. His readers are made to consider the West’s view of the East as a distorted one, and the distortion – the stereotype – is called ‘Orientalism’. In Orientalism Said stated, The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest colonies, the source of its civilisations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of ‘Other’ (Said, Orientalism, pp. 1–2).

Figure 6.41 | Henri Matisse, Blue Nude, 1907, oil on canvas, 92.1 × 140.3 cm, Baltimore Museum of Art:The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland, BMA 1950.228.

Source: Baltimore Museum of Art. Photography by Mitro Hood. Artwork: © Succession H. Matisse/ DACS 2015.

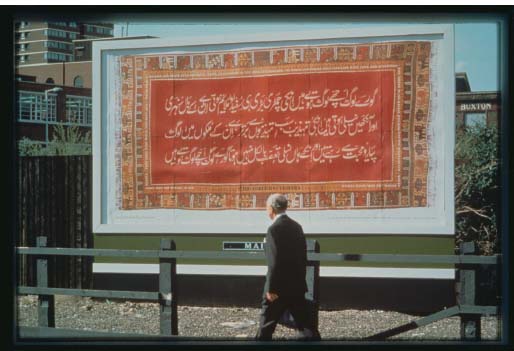

Figure 6.42 | Rasheed Araeen, The Golden Verses, 1990–1991, billboard poster, 300 × 600 cm.

Source: Commissioned and produced by Artangel.

The ‘ism’ of Orientalism, according to Jonathan Harris, signals both its constructed nature and association with imperialism, colonialism and economic penetration (Harris, Art History: The Key Concepts, p. 222). Do you think that our focus on the label ‘Orientalism’ is in fact an act of Orientalism itself?

Twentieth-century stereotypes and discrimination