Introduction

The book you are holding is not a history of art and architecture. It is a guide to understanding, interpreting and, ultimately, appreciating works of art and architecture. Of course, it includes some history, but its fundamental purpose is to help you ‘read’ a work of art or a building so that you can explain and discuss it in an informed and meaningful way and recognise its significance and the value of its qualities.

Unlike many books about art and architecture, this one is not organised in a chronological way. Although art and architecture's sequential development is an important part of understanding the subject, and this book does not ignore that, a thematic organisation has been adopted. In part, this is because it allows for effective relationships to be made that really assist understanding and interpretation, such as when examples from different art-historical periods are compared and contrasted. Since works of art and architecture are products of time and place, social and political systems, individual aspirations and so on, a thematic approach also demonstrates how the study of them is inescapably related to other disciplines and knowledge bases, from history to sociology, mathematics, science and technology to economics, psychology and beliefs, let alone to other cultural pursuits such as literature, music, theatre, dance, film and so on.

Another reason for the thematic arrangement lies in the book's dual purpose. Not only is it intended to serve as an effective guide for both lay readers and those who want to extend and expand their knowledge and understanding, but it is also a helpful and constructive ‘tool’ for students and prospective students of the AQA A-level examination in History of Art (Art of the Western World).

In general, there are two fundamental approaches (we might call them methodologies - that is, procedures applied to exploring and examining) in the history of art. Essentially, one is concerned with what we see and the other with what we know.

When we look at works of art and architecture we see a number of elements. In a painting it would be such things as colours, lines and shapes, the way the artist has applied the paint, the size of the painting and so on. These are the formal features and we would hope to understand and interpret the painting as a result of identifying and deciphering these.

The other methodology may be prompted by what we see but is more about the knowledge we already have or seek to have. This concerns the historical, social, cultural, psychological and other circumstances of a work's production and subsequent reception; in other words, the contexts of the work of art or architecture.

Although they appear to consider different things, these methodologies are not independent of each other. It would be fatuous to think that we could look at the formal characteristics of a work of art or architecture and hope to gain anything approaching a reasonable understanding of its purpose and meaning. Equally, even a thorough acquaintance with its subject matter (or its function, in the case of architecture), the circumstances of its creation, the personality of its creator and so on, would only take us so far in understanding and appreciating the work's aesthetic qualities or its capacity to ‘move’ us. In fact, the two methodologies outlined above must be ‘used’ alongside each other in order to develop a richer, more nuanced understanding and appreciation of art and architecture.

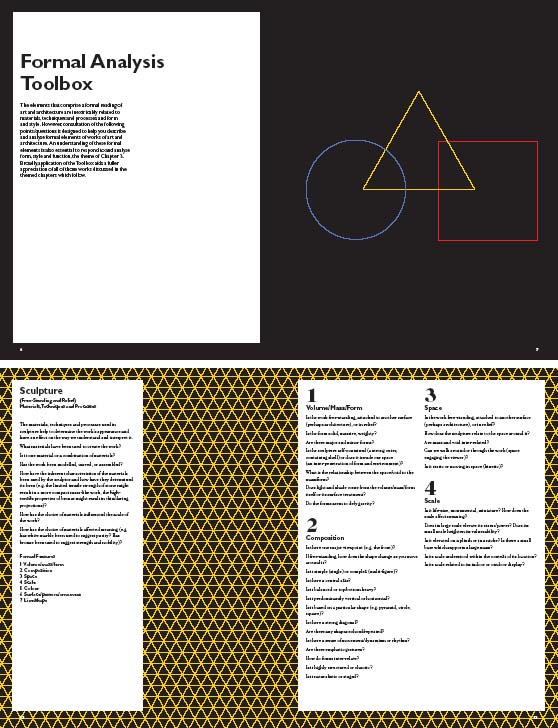

This book has been organised so that you can use these two methodologies - formal analysis and contextual knowledge - side by side. The shorter, but no less important, section is the Formal Analysis Toolbox, designed as a comprehensive list of questions that may be posed in relation to any work of art or architecture. The greater part of the book, which is organised thematically, applies contextual knowledge and analysis, as well as formal analysis, to examples selected as appropriate illustrations of the themes of each chapter.

Formal Analysis Toolbox

The Formal Analysis Toolbox is a series of questions that you would ask when looking at works of art and architecture. Each question focuses your attention on a particular feature of a work, and your ‘answers’ will lead to a thorough understanding of the way it has been created and how it communicates on a formal level, that is, by the way it looks.

Implicit in the Toolbox questions is the proposition that the analysis may be developed from mere description of how something looks to one that points to interpretation. For instance, asking if the composition (the organisation and arrangement of elements) of a painting might be unstructured, or informally arranged, or dynamic and exciting, or harmonious, well-balanced and rigid, suggests that any of these is important to understanding the work and would, in all likelihood, contribute to our interpretation of it. Equally, identifying what materials are visible in a building and whether the choice of material affects a building's structure is not just about describing what you see; the implication is that distinguishing such things may facilitate a more meaningful interpretation of the building.

The Toolbox is particularly useful for those new to art-historical analysis. It provides a starting point, a way 'into' looking at works of art and architecture, which, after all, are frequently complex, difficult and chalenging things, at least if we want to get something more than a superficial experience from looking at them.

Although the Toolbox can be used as a standalone guide to 'reading' works of art or architecture, used alongside the examples discussed in the thematic sections of this book, it will provide you with a comprehensive and effective means of understanding and lead you to meaningful interpretation.

The Formal Analysis Toolbox has also been designed to meet the requirements of the first teaching and assessment unit of the AQA's A-level History of Art (Art of the Western World) Specification (curriculum). Entitled 'Visual Analysis and Interpretation', this unit is about how to describe the formal features, subjects and themes of works of art, and the formal features, building types and functions of architecture. It is also concerned with how to discuss, interpret, comment on and evaluate works of art and architecture.

Themes in art and architecture

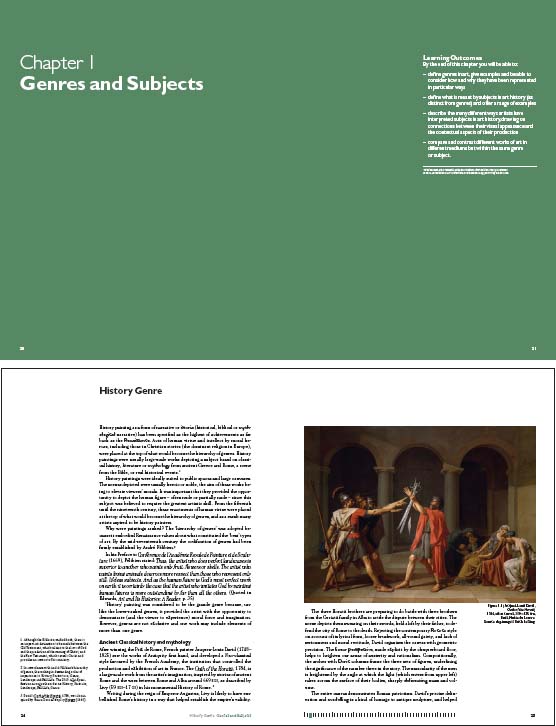

Each of the six chapters of this book discusses and interprets a range of examples in relation to fundamental art-historical themes. However, you must not think that simply because a particular work of art appears, let's say, as an example of how patronage operates, that this is the only way you should understand it. It is well to remember that there are countless interpretations of a work of art or architecture since different people at different times and in different places have looked at, written and spoken about it. Some of these provide us with valuable, helpful and effective ways of looking, interpreting and evaluating, but however perceptive, no one of them is definitive simply because there is no such thing as the definitive interpretation. Therefore, many of the examples in this book that have been interpreted in relation to a particular theme can also be interpreted in relation to other themes, and this point is made throughout the six thematic chapters. Moreover, once you have grasped the way that works of art and architecture can be thematically interpreted, you might substitute the given examples for some of your own.

The first three thematic chapters – Genres and Subjects; Materials, Techniques and Processes; Form, Style and Function – discuss examples using both formal and contextual methodologies in relatively equal part. The final three chapters – Social and Historical Contexts; Patronage and the Status of the Artist; Gender, Nationality and Ethnicity – almost exclusively employ a contextual methodology. But the point should be made again that these methodologies are not independent of one another and a fuller and richer understanding will result from interpreting the works from both positions.

As with the Formal Analysis Toolbox, the six chapters that discuss themes in art and architecture meet the requirements of the AQA's A-level examination in History of Art (Art of the Western World). The second teaching and assessment unit is called 'Themes in History of Art' and is about understanding and interpreting specific examples in relation to these themes.

The third and fourth teaching and assessment units of the AQA Specification require both formal and contextual analysis of works of art and architecture, the only difference being that these are now selected from specific periods of time (generally a century) and discussion should be in more depth and detail than for the first two units.

Other features of this book

This book offers a number of other important features. It has a Glossary of terminology (art-historical and other), with a pronunciation guide where necessary. Terms in the Glossary are emboldened when they first appear in each chapter. At the end of each chapter there is a Summary Exercise that tests how well you have understood what the chapter has been about. There are also questions similar to those found in the AQA History of Art examination, and Checkpoint Answers  that pick up on important points made in the chapter. Finally, the companion website directs you to reading, websites, DVDs and other resources, as well as listing some useful books that have not already been referenced.

that pick up on important points made in the chapter. Finally, the companion website directs you to reading, websites, DVDs and other resources, as well as listing some useful books that have not already been referenced.

This book offers an approach to the discipline that will not be beyond criticism – far from it – but its aims are simple: to provide an accessible text for anyone interested in art and architecture, however knowledgeable they may or may not be; to offer a constructive and, hopefully, helpful guide for students, prospective students and teachers of the AQA History of Art Specification; to inspire inquiry, encourage links with other subject areas and add fuel to the AQA's Extended Project Qualifications (EPQ). Finally, the book's definitive aim is to make history of art interesting, enjoyable and fulfilling.