note

These cutting instructions are written for right-handed people. If you’re left-handed, you’ll want to do the opposite of what’s described here. That includes moving the rotary cutter blade to the opposite side of the cutter and cutting on the opposite side of the ruler.

Rotary cutting is best done from a standing position. The vantage point gained by standing and the additional pressure you can exert on the ruler make for more accurate cutting. If possible, use your rotary cutter on a table that you can walk all the way around. This will minimize the number of times you have to move the fabric you’re cutting.

tip

Rotary cutter blades are incredibly sharp. Always cut away from yourself and keep the blades covered when not in use. Avoid moving the cutter back and forth in a sawing motion, as this can chew up the fabric edges.

Make sure your fabric is free from wrinkles before you start cutting. Take the time to press the fabric before you start to work with it.

Unless otherwise noted in the project directions, always line up your ruler with the grain of the fabric. Hold the ruler firmly in place with your left hand, keeping all your fingers on top of the ruler and out of the cutter’s path.

Prepare to cut by lining up the blade with the ruler’s right edge. Use even pressure to run the cutter along the edge of the ruler, making a clean cut through the fabric. As you cut, be sure to keep your fingers clear of the blade.

Change your rotary cutter blade regularly. Dull or nicked blades make accurate cutting difficult and can cause ugly little pulls in the fabric. If it’s taking more than one pass with the cutter to get through the fabric, it’s time to change the blade.

tip

Save the plastic case that your rotary cutter blade came in and use it to dispose of the old blade safely or to store the blade for another use. Even after they’re too dull to cut fabric, rotary cutter blades can still cut paper, template plastic, and other materials.

Most of the projects in this book instruct you to start by cutting strips that are a particular size “× width of fabric.” Quilting fabric is usually 40″–44″ wide; so, if the instructions call for cutting a strip 6″ × width of fabric, that means a strip of fabric that measures 6″ × about 40″–44″.

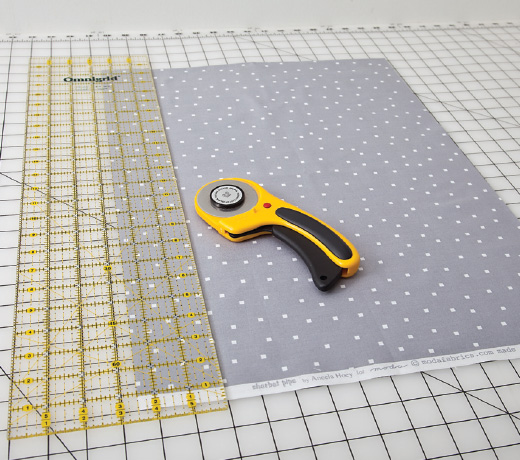

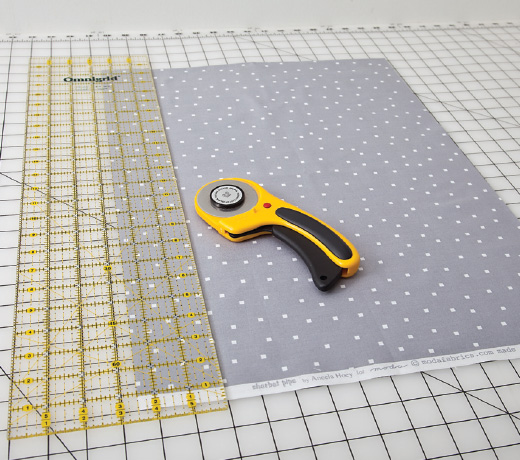

1. Place fabric, folded selvage to selvage, on the cutting mat so the folded edge is nearest you.

2. Place a 6″ × 24″ ruler on top of the fabric. Match a horizontal line on the ruler to the fold and slide the ruler to the cut edge on the right side of the fabric.

3. Square up the fabric by cutting off a tiny strip of the cut edge along the right side of the ruler, creating a straight edge that is at a right angle to the fold.

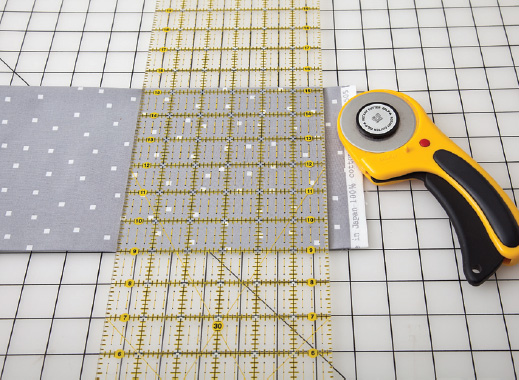

4. Move to the opposite side of the table. (If you can’t move around the table, carefully turn your rotary cutting mat instead.) Now the straight edge is on the left side of the fabric, and the folded edge is away from you.

5. Use the lines on the ruler (not the lines on the cutting mat) to measure the width of the strip you want to cut, starting from the left edge; cut along the right side of the ruler. Move from left to right across the fabric as you continue making cuts.

tip

When cutting strips wider than 6″, use an additional ruler (a large square one works well) against the left side of your 6″ × 24″ ruler, always cutting the fabric along the right edge of the 6″ × 24″ ruler.

Because fabric is usually 40″–44″ wide, strips longer than this need to be cut along the length of the fabric (parallel to the selvage edge), rather than the width. To make an accurate cut, you’ll need to refold the fabric to a size that fits on your mat.

Instead of folding the fabric along the existing crease, fold it in the opposite direction, bringing the cut edges together and matching the selvages along one side. Fold the fabric once or twice more, keeping the selvages along one side lined up, until you can easily place the fabric on your cutting mat.

You may need to let one end of the fabric hang off the end of the table. Just be careful not to let the weight of the fabric pull the nicely folded edge out of alignment. If necessary, hold the fabric in place with a book or another heavy object (set out of the way of your cutting tools).

Trim away the selvage to square the edge; use this edge as the straight edge for cutting the pattern pieces. You’ll be cutting through more layers than when cutting along the width, so be careful to realign the edge of the fabric as needed.

Cutting 60° angle

Most 6″ × 24″ rulers include guides for cutting 30°, 45°, and 60° angles. To use these guides, tilt the ruler to the left until the guide you want is lined up with the bottom edge of your fabric. Then cut along the right side of the ruler, just as you would if you were making a standard 90° cut.

1. Place your template on the fabric, lining up any seam markers or grain-line indicators.

2. Trace around the template with tailor’s chalk or a water-soluble fabric marker (avoid disappearing ink, as it may disappear before you’re finished). Transfer all the necessary markings onto the fabric.

3. Cut out the template shapes from the fabric, using a rotary cutter and a ruler for straight edges and scissors for curves.

tip

Unless a pattern instructs you to do otherwise, always trace around template shapes with the top side of the template facing up. For some shapes, tracing around an upside-down template will produce a mirror image that won’t work in your quilt.

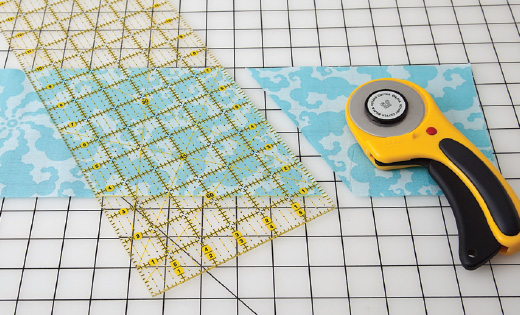

Fussy cutting is the common term for cutting a print fabric to highlight or center a particular part of the print. One easy way to do this is to cut a piece of translucent template plastic the size of the fabric piece you need; then move it around on top of the fabric until you’ve framed the part you want. Cut the fabric by following the directions for cutting template shapes (at left).

The patterns in this book use a ¼″ seam allowance. I recommend using a ¼″ patchwork piecing foot on your sewing machine.

If you’re not confident about maintaining an even seam allowance, practice with scraps before starting your actual project. Sew together two 2″ × 2″ squares, press the seam open, and measure the pieced unit. With an accurate ¼″ seam allowance, the pieced unit will measure exactly 2″ × 3½″.

tip

When sewing together a pieced block and a solid piece of fabric (a piece of sashing, for instance), always keep the pieced block on top. This lets you keep an eye on the block’s seam allowances to make sure they don’t get pulled askew by your machine’s feed dogs.

I usually pin before sewing, inserting the pins through all the layers on both sides of each seam allowance. If there’s a large space between seam allowances, I place a pin or two there as well.

Keep a pincushion next to your machine and remove the pins as you sew. All this pinning may seem tedious, but it will lead to accuracy.

When pinning together long rows of blocks or sashing, I find it easiest to line things up by placing the pieces across the end of a table. I recommend beginning in the center and working outward, instead of starting at one end. If your rows are off, doing it this way will ease in any differences across the quilt top rather than making it progressively worse as you move from one side to the other.

I press my seams open. It takes a bit more effort than pressing them to one side, as many quilters do, but I think the results are worth it. If you press the seams open, your finished blocks will be more precise, will lie flatter, and will be easier to machine quilt in an allover pattern.

Place your work right side down on the pressing surface and use your index finger to press open the seam. Run the point of your iron down the seam; then place the entire iron over the seam and press firmly. Flip the work to the other side and gently press the front (right) side.

For long seams, I usually place my work faceup on the pressing surface, press the seam to one side, and then flip the project to press the seam open.

Some quilters believe that pressing seams open will have a negative impact on the quilt’s structural integrity. I have never found this to be true when using contemporary materials and machines. As long as you’re using a good stitch and good materials, a quilt with pressed-open seams should be perfectly sturdy.

The type of stitch you use can affect the look of the finished appliqué. If you have a machine with lots of stitches, you may want to experiment with different stitches to find the one you like best. Machines with many stitch options may also have a special appliqué foot, which can make it easier to see what you’re doing. Consult your machine manual for instructions on using the different stitches and feet.

On a simpler machine, you may only have the option of using a zigzag or a buttonhole stitch. Use the zigzag stitch for larger appliqués with finished edges, as I did for Looptastic (page 86), and a buttonhole stitch for raw-edge fusible appliqués, as in Owl Eyes (page 70).

Finished-edge appliqué on Looptastic

1. Fit your machine with a new needle and adjust the settings for machine appliqué. Depending on the machine, this may mean using a specialty appliqué stitch, a satin stitch, a buttonhole stitch, or a plain zigzag stitch.

2. Begin on the right side of an appliqué shape. Bring the needle down in the right-hand position, just outside the appliqué; start stitching, encasing the edge of the appliqué in the stitches. Raise the presser foot to pivot the block as necessary. The needle should always be down before you raise the presser foot or pivot the block.

Stitching around Looptastic appliqué

3. When you reach your starting point, backtrack a few stitches; then remove the project from the machine and use tweezers or a seam ripper to gently pull the loose threads to the back side. Trim the threads and move on to the next appliqué.

Stitching around Owl Eyes appliqué

tip

When pivoting around convex curves and angles (such as the outside of an oval or a loop), the needle should be down in the right-hand position, just outside the appliqué. When stitching around concave curves and angles (such as the inside of an oval or a loop), the needle should be down in the left-hand position, through the appliqué piece.

This process takes some floor space, so many of us end up doing it in a different part of our home than we normally use for sewing. Even though I have a sewing room, I find this step always involves shuffling furniture, hauling supplies into another room, and chasing away inquisitive cats. It’s worth it, though, because taking the time to make a good quilt sandwich makes the next step—machine quilting—go much more smoothly.

1. Start by placing the batting on a clean, smooth floor. Spread the quilt top on the batting, smoothing out any wrinkles. (You may actually need to crawl on top of the quilt to do this.) Trim the batting to within about 2″ of the quilt top. (A)

A Spread the quilt top on the batting, smoothing out any wrinkles.

2. Starting at the top of the quilt, carefully roll up the layered batting and quilt top. (B)

B Carefully roll up the layered batting and quilt top.

3. Continue until the batting is completely rolled up; then set the roll aside with the cut edge down. Don’t worry about pinning the batting roll. The natural tendency of most battings is to cling to fabric, so the roll should hold itself together without any help from you.

4. Spread out the quilt backing fabric on the floor, right side down. Starting at the bottom of the quilt, use painter’s tape to secure the edge of the quilt backing to the floor. Move to the opposite (top) edge and, pulling the quilt backing ever so slightly toward you, tape the center top of the backing to the floor. Repeat with the left and right sides and each of the corners—each time pulling very gently, but not stretching, to make sure the quilt back is completely smooth. Continue taping the edges until the backing is secure.

5. Bring back the batting roll and, starting at the bottom edge, slowly unroll it onto the taped backing. You should have a few inches of leeway on all sides, but you want to make sure of two things: (1) all parts of the quilt top are inside the edges of the quilt backing and (2) the rows of blocks in the quilt top are perpendicular to the sides of the quilt backing. (C)

C Slowly unroll the batting roll onto the taped backing.

tip

This is your only chance to get the alignment of the quilt right. If you see that it’s off, don’t hesitate to reroll the batting and start over!

6. Once again, smooth out the quilt top and batting. I usually do this by starting at the bottom and crawling up the center of the quilt, smoothing as I go. You want to make things smooth, while also being careful not to warp the fabric as you work. If you notice that your smoothing is making the blocks wonky, ease up a bit and work them back into the right shape. (D)

D Smooth out the quilt top and batting.

7. Starting in the center of the quilt, pin curved safety pins through all the layers (top, batting, and backing). I recommend placing the pins in a grid pattern, with a pin about every 6″. You can definitely use more pins, but keep in mind that you’ll have to remove them as you quilt—an excessive number of pins may hamper your quilting progress. (E)

E Pin curved safety pins through all the layers.

8. Once you’ve finished pinning, remove the tape and trim the quilt backing to the same size as the batting. You’ll want to handle the quilt sandwich with some care. However, if you’ve done a good job of smoothing and pinning, you should be able to flip the sandwich over and have the back be just as smooth and even as the front.

Machine quilting at home can be an economical, personal, and fun way to finish your quilts. I quilted all the projects in this book on a home sewing machine, using either straight-line quilting with a walking foot or free-motion quilting with a darning foot.

• Always start each new project with a new needle. I recommend a 90/14 universal or quilting needle.

• Use high-quality thread. Most quilters prefer 100% cotton, but today’s 100% polyester threads also work well for machine quilting. Avoid poly/cotton blends or hand quilting thread, which has a waxy coating that’s incompatible with machines.

• Quilting uses a lot of thread! Wind a few extra bobbins before you start.

• Stock your quilting area with a seam ripper, thread snips, and a container for collecting your basting pins as you remove them.

• Engage your machine’s needle-down function (or get in the habit of using the hand wheel to manually put your needle down whenever you stop). This will hold your place when you stop, ensuring that your rows of stitching stay straight.

• The weight of your quilt hanging off the table or into your lap can work against what your sewing machine is trying to do. Make things easier by keeping the entire quilt on the tabletop while you work. Rest the quilt on your chest or even over your shoulders rather than letting it drop down into your lap.

• Machine quilting can be physically strenuous. Take breaks to relax your arms, shoulders, and neck.

• If it’s been more than a year since your machine’s last tune-up, it may be a good idea to have it serviced before you attempt to machine quilt.

• Machine quilting creates lots of lint. Consult your machine’s manual for instructions on how to clean your machine properly. Then get in the habit of cleaning it after you finish each quilting project.

The feed dogs on your sewing machine are like little teeth that cycle up and down under the fabric, pulling it through the machine. This works well when you’re sewing through just one or two layers of fabric, but something as thick as a quilt needs a little more help. A walking foot (sometimes called an even-feed foot) adds a second set of feed dogs on top of the fabric. With feeds dogs on both the top and the bottom, your machine can sew through a quilt sandwich with ease.

• Follow the manufacturer’s directions to install the walking foot. Most walking feet have a bar or claw that needs to be fitted above or around the needle screw.

• Test the tension and stitch length on a practice quilt sandwich. You may find that slightly increasing both the stitch length and the tension results in a nicer-looking stitch.

• Start at or near the middle of your quilt. For instance, if you’re sewing parallel lines across the quilt, start with a line through the center and work your way out to the sides, alternating the direction of each row of stitching.

• Moderate your speed. Big, clunky walking feet are fabulous tools, but they’re not built to move as quickly as other feet. Using a walking foot at a very high speed can result in ugly stitches and possible damage to the foot itself.

• Avoid stitching in-the-ditch, or right on the seamline. Stitching ¼″ away from the seams rather than right on top of them looks more polished—and is much easier to do!

Stitching parallel lines about ½″ apart produces a simple quilted look and beautiful texture. Don’t worry if your lines aren’t perfectly straight. That’s part of the charm.

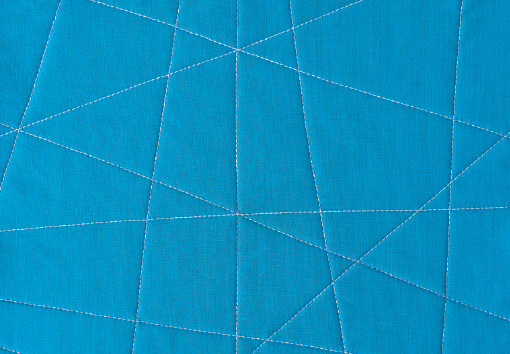

Use a piece of blue painter’s tape to randomly mark a line across your quilt. Sew along the line, reposition the tape, and repeat to create a series of crisscrossing random lines across the quilt top.

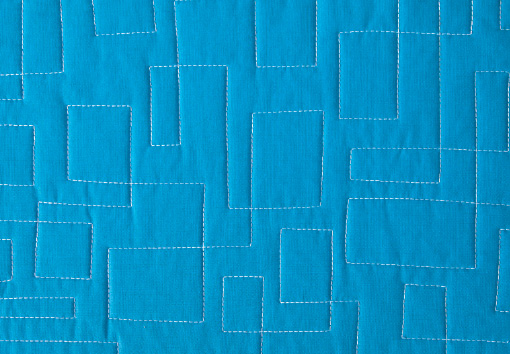

Stopping and pivoting to make clusters of small boxes can be a fun way to quilt a smaller project.

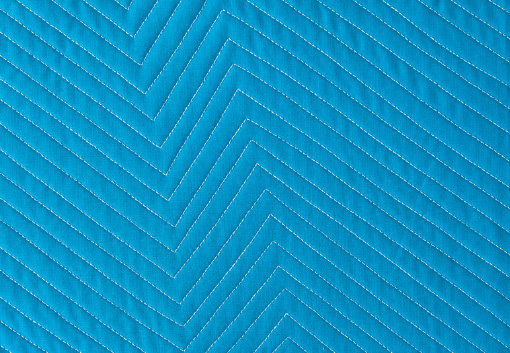

Stitching a simple shape, such as this chevron, and then echoing it on both sides can produce striking results.

Most sewing-machine operations rely on the feed dogs pulling fabric through the machine to create uniform stitches. For free-motion quilting, however, you lower or otherwise disengage the feed dogs, which allows you to control the shape and size of the stitches and makes it possible for you to stitch in any direction. Lowering the feed dogs frees you to use the darning foot (sometimes called a free-motion quilting or embroidery foot) to draw circles, loops, or anything else you want on your quilt.

tips for success

• Free-motion quilting tends to be most successful at higher speeds. That doesn’t mean you have to go as fast as you can—just fast enough to achieve smooth, fluid results.

• The key to free-motion quilting is striking a balance between the machine’s speed (affected by pressure on the pedal) and the speed at which you move the quilt sandwich. If your stitches are too long, it usually means you’re moving your quilt too quickly or with jerky motions. If your stitches are too small, it usually means you’re not moving the quilt fast enough.

• Because you’re not using the feed dogs, it’s not necessary to push the quilt away from you as you work. In fact, I find it easier to pull the quilt toward me, because that makes it easy to see the work that I’ve just done.

• Tension problems aren’t always obvious from the top. Check the back of your quilt frequently to make sure everything looks right. If the bobbin thread on the back of your quilt appears to be pulled into a straight line, try increasing the thread tension.

• I find that grabbing handfuls of the quilt sandwich makes it easier for me to move the whole thing around. Other people prefer to guide the quilt with their fingertips. Experiment with different grips to find what works best for you.

Consult your machine manual for information about how to prepare the machine for free-motion quilting. For most machines, you will need to fit the machine with a darning or free-motion quilting foot, set the stitch length to zero, and lower or cover the feed dogs.

1. With your quilt sandwich in the machine, manually lower the needle and bring it back up again, pulling the bobbin thread through to the top of the sandwich. Put the presser foot down and make several stitches in place to create a knot.

2. Begin to move the quilt sandwich, stitching your chosen pattern for just an inch or so from where you started. Pause, making sure the needle is in the down position, and trim the loose thread ends so they won’t get tangled in your work.

3. Repeat Steps 1 and 2 every time you have to rethread the machine, always making sure to bring the bobbin thread to the top and trim the loose ends.

4. Continue quilting, using your hands to guide the stitching in your desired pattern and removing safety pins as you come to them. As you practice, you’ll start to get a feel for how much pressure to put on the pedal and how fast to move the quilt sandwich.

tip

It may help to think of your needle and thread as a pen and your quilt sandwich as paper. The twist is that with free-motion quilting, the pen stays in one place while the paper moves beneath it.

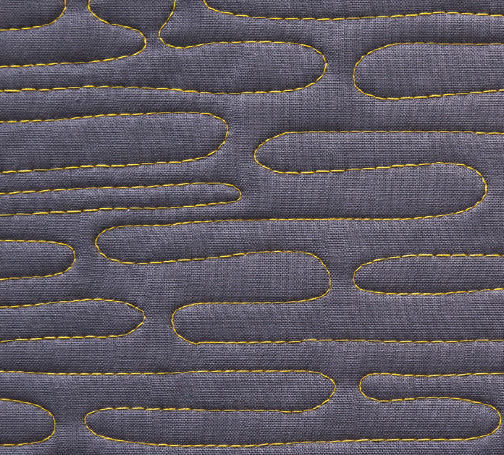

This curved, meandering stitch creates a beautiful texture that’s accentuated when the quilt is washed.

Turning curves into boxes lends a whimsical, retro look.

Wonky boxes with crisscrossing lines impart a modern crosshatched look.

A meandering lightning rod pattern complements bold fabrics.

Stacked ripples contrast with regular blocky piecing.

Drawing a 2″ grid on the quilt top takes time, but it makes it easy to quilt patterns repeated in each square, such as this dogwood flower.

Binding is the finishing frame around a quilt. My favorite method is straight-grain binding made from strips cut along the grain of the fabric rather than on the bias. All the quilts in this book were made with this type of binding, which is machine sewn to the front of the quilt and finished by hand on the back.

1. Cut binding strips along the fabric grain and trim away the selvages. Sew the strips together end to end, using ¼″ seam allowances, and press the seams open. With the wrong sides together, press the entire binding in half lengthwise. (A)

A Sew the binding strips together.

tip

Straight-grain binding, or using pieces sewn together end to end, is perfect for making patchwork or scrappy binding. That can mean inserting one or two contrasting pieces between longer strips or making the entire binding from small pieces. Experiment and have fun! Just keep in mind that additional seam allowances add bulk. The extra bulk may make it difficult to achieve perfectly mitered corners, so try to keep the seams between strips away from the corners.

2. Prepare your quilt for binding by trimming all the layers even with the quilt top and squaring up the quilt top if necessary. Start in the center of one side and pin the raw (unfolded) edge of the binding to the quilt’s edge. When you reach a corner, fold the binding up at a 45° angle. (B)

B Trim all the layers even with the quilt top.

3. Fold the binding back toward the quilt, aligning the fold with the top edge to create a mitered corner. (C)

C Align the fold with the top edge to create a mitered corner.

4. Fold down the mitered corner and pin it in place. (D)

D Pin the corner in place.

5. Continue pinning, repeating Steps 2–4 at each corner, until you reach the point where you started. Bring together the 2 ends of the binding, fold each piece back onto itself so the ends are butting, and press in place. (E)

E Bring together the 2 ends of the binding and press in place.

6. Match the creases you’ve just pressed and sew the ends together along the crease. Trim the seam allowance to ¼″, press the seam open, and pin the binding back in place. You should now have continuous binding pinned all the way around your quilt sandwich. (F)

F Sew the ends together.

7. Use a ¼″ seam allowance to sew the binding to the quilt. When you come to a corner, sew up to—but not beyond—the miter. Stop stitching and trim the threads. (G)

G Sew the binding to the quilt.

tip

If you’d rather not use pins, feel free to sew the binding on without pinning it first. Leave about 6″ of extra binding at your starting point. Then sew the binding to the quilt edge, folding miters at each corner, just as if you were pinning. Stop several inches from where you started and refer to Steps 5 and 6 to join the two ends of the binding.

8. Fold back the mitered corner. Resume your stitching at the corner, repeating Step 7 at each of the following corners until you reach the point where you started. (H)

H Continue sewing around the quilt.

9. Fold the binding to the back of the quilt—the fold you pressed into the binding earlier and the mitered corners should make this easy. Use pins or binding clips to secure a section of the binding in place.

10. To create a knotless start for hand finishing, fold a length of thread in half and thread the fold through the needle. Pull through far enough that the loose ends are near the eye of the needle and the loop is at the other end (where a knot would normally be). Pull the needle through the quilt back and batting, near the edge of the binding, leaving the end loop sticking out just a bit. Bring the needle through the edge of the binding and then back through the loop. Pull the needle until the loop closes and the thread is anchored securely. (I)

I Create a knotless start for hand finishing.

11. Hand stitch the binding in place, pushing the needle through the quilt back and batting and pulling it back up through the very edge of the binding. Continue sewing, making a stitch about every ¼″. (J)

J Hand stitch the binding in place.

12. When you reach a corner, sew right up to the quilt’s edge before folding back the mitered corner and continuing onto the next side. (K)

K Sew up to the quilt’s edge before folding back the mitered corner.

13. Continue until the binding is completely stitched in place. (L)

L Finish the binding.

tip

Take good care of your finished work. Quilts made with cotton generally can be machine washed and dried. I use cool water, a gentle wash cycle, and gentle detergent, and I tumble dry on low heat. If you’re concerned about colors bleeding, consider trying a color catcher product. Designed to soak up any loose dye in a wash cycle, these products are usually available where laundry soap is sold.