3

MAJOR DEAL

Covenant as Vocation

WRITTEN IN STONE: WHY TWO TABLETS?

With Yahweh’s dramatic appearance and gracious invitation as a prelude, God issues instructions to the people appointed as his representatives (20:1-17). He later calls these instructions the “Ten Words” (Exodus 34:27-28). They are the official terms of the covenant Yahweh is making with Israel (see Exodus 31:18). Unlike all the other commands given at Sinai, God speaks them directly in the hearing of all the people.

DECALOGUE

Although it’s standard to call them the “Ten Commandments” in English, the Bible never does. They are always the “Ten Words.” This is where the term “Decalogue” comes from—it’s made up of the Greek words deka (ten) and logos (word). “Word” in Hebrew (dabar) has a wider range of meaning than “word” in English. It can refer more generally to a “matter” or “thing” as well as a word. As we will discover, the Ten Words contain more than ten commands.

Later, he inscribes them on two stone tablets. Why two? One of the biggest misconceptions about the Ten Commandments is that they did not all fit on one tablet. The vast majority of artistic representations of Moses and the two tablets presume that he’s holding “Volume 1” and “Volume 2.” However, we know from the biblical text that the commands were written on both sides of each tablet: “And Moses turned and he went down from the mountain, and the two tablets of the covenant document [eduth] were in his hand, tablets inscribed on both sides, inscribed on front and back” (Exodus 32:15, author’s translation).

The Hebrew word eduth, sometimes translated “testimony,” is a plural technical term for treaty documents. As with segullah above, eduth is a word found in related languages, such as Akkadian, to refer to treaty documents.1

Given the brevity of the Ten Words in Hebrew, just 171 words total, they easily could have fit on two sides of a single stone tablet, even if that tablet was not much larger than Moses’ hand. (This paragraph and the next total 200 words.) So why produce two tablets? For the answer we must turn to other ancient Near Eastern treaty documents. What we find is that it was standard practice to make duplicate copies of a treaty document, etched in stone. One copy belonged to each party, who would put it on display in their respective temple.2 This way, each of their gods could see the terms of the treaty and watch to ensure that both parties remained faithful. Here’s a Hittite example from a treaty between Suppiluliuma of Hatti and Shattiwaza of Mitanni (try saying those names five times fast!). In each king’s respective territory, the tablet is deposited in the temple so that the gods can oversee the agreement:

A duplicate of this tablet has been deposited before the sun-goddess of Arinna, because the sun-goddess of Arinna regulates kingship and queenship. In Mitanni land [a duplicate] has been deposited before Teshub, the lord of the [sanctuary] of Kahat. At regular [intervals] shall they read it in the presence of the king of the Mitanni land and in the presence of the sons of the Hurri country.3

In the case of Israel’s covenant, only one deity can ensure the covenant faithfulness of both parties: Yahweh. For that reason, both copies of the treaty will be placed in the most holy place of the Israelite tabernacle, under God’s watchful eye. The duplicate tablets indicate that both parties—Yahweh and Israel—are bound by the covenant between them.

Another myth about the Ten Commandments is that they divide neatly into two groups of laws—one pertaining to God and another pertaining to people. This unfortunate, deeply entrenched misunderstanding goes back many centuries. To cite just one example, the Heidelberg Catechism states:

Q. How are these commandments divided?

A. Into two tables. The first has four commandments, teaching us how we ought to live in relation to God. The second has six commandments, teaching us what we owe our neighbor.4

The artificial division between commands demonstrates an inadequate view of how covenants work. In the covenant community, every part of life is an expression of worship and loyalty to the God who has committed himself to these people. How they treat others reveals their heart toward God. Consider this example: after David sins by lusting after his neighbor’s wife, committing adultery with her, and then murdering her husband (breaking three of the Ten Commandments), he responds to the prophet Nathan’s confrontation by saying, “I have sinned against the LORD” (2 Samuel 12:13). Later he prays to Yahweh, “Against you, you only, have I sinned and done what is evil in your sight” (Psalm 51:4). For David, the so-called interpersonal commands have everything to do with God.

In the covenant community, every part of life is an expression of worship and loyalty to the God who has committed himself to these people. How they treat others reveals their heart toward God.

Conversely, if just one Israelite rebels against Yahweh, it puts the entire community at risk of God’s judgment. An obvious example is Achan, who kept some of the plunder of Jericho in spite of God’s clear instruction not to do so, making Israel vulnerable to defeat at the battle against Ai (Joshua 7). All ten of these commandments reflect a proper disposition toward God, and all ten affect the entire covenant community. By keeping them, the Israelites not only honor God but also ensure that the community of faith can flourish.

I’ll never forget a sermon I heard as a child shortly following the Jim Bakker scandal. The television personality and founder of PTL was caught embezzling funds, lying to donors, and allegedly raping a woman. Our pastor did not go into detail, but lamented that “Christians have become the butt of every joke.” He was right. One pastor’s fall into sin reflected poorly on evangelicalism as a whole, confirming what many suspected: Christianity is full of hypocrites, and preachers can’t be trusted. It happened again in 2006 with Ted Haggard, then president of the National Association of Evangelicals, when he was caught in a sex-and-drug scandal involving a male escort.

Like it or not, that’s what happens when one member of a company, a sports team, a club, or a faith community behaves badly. It reflects on the entire group and what they represent. There is no such thing as private sin. What we do matters. Not just to us, but to everyone on our team.

With Israel, the problem is even more serious than guilt-by-association. Because the whole nation collectively entered into the covenant with Yahweh, one person’s unfaithfulness put everyone else at risk of punishment by defiling the land (see Leviticus 18:28). It was all-for-one and one-for-all.

People often assume that because the Ten Commandments were written in stone, they apply to everyone throughout history, unlike the myriad specific laws in the Torah, which were intended for ancient Israel. But based on what we know of treaties from that time, it should be clear that this line of thinking is out of touch with ancient culture. The Ten Commandments are prefaced with a clear statement of their specific audience: “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery” (Exodus 20:2). The commands contain language very specific to that ancient culture (“Do not covet your neighbor’s ox”). They are never communicated to other nations. When the Old Testament prophets pronounce judgment on neighboring peoples (e.g., Amos 1–2), they are not measured against the Ten Commandments. Instead, they are measured against a standard of basic human decency. Are they arrogant jerks? Have they taken advantage of other nations’ misfortune or been unduly violent? These standards do not clearly arise from the Ten Commandments.

No, the commands in this ancient context are for the Israelites alone.5 The torah was a gift to Israel, the people of Yahweh. They signed on to it. But what exactly have they agreed to do?

THE GIFT OF LAW: A MANDATE TO FREEDOM

The Ten Commandments are among the most famous passages of the Bible. Even those not raised in the synagogue or church often have a vague idea of what they are—God’s divine decree about what people are not supposed to do. The unfortunate thing about this is that the commands are usually divorced from their context. If taken alone, people focus on the “Thou shalt nots,” and they miss the dramatic story of God’s deliverance that sets the stage.

Context is everything. I grew up with the most frugal grandparents on the planet, I thought. We were not allowed to turn on lights until the eye strain became unbearable. We could not waste paper, or water, or any bites of food. Leftovers were always saved for the next meal. Laundry was hung outside to dry. Old clothing was mended first before becoming quilts or perhaps rags. Old carpet became walkways between rows of beans and carrots in the garden. Zip-lock bags were washed for reuse. Scraps of wood were burned in the wood stove, upon which the tea kettle whistled and the pot of porridge cooked. All this frugality made much more sense to me when, as an adult, I visited “the old country” with my Dutch grandma, whom we called “Oma.” The Netherlands is a land reclaimed from the sea, where wind is harnessed to pump water, grind grain, press oil, and produce electricity. During World War II, when Oma was a young woman responsible for her motherless siblings, food was so scarce that they ate tulip bulbs. Walking in her wooden shoes for two weeks helped me to understand why she valued frugality so highly. In context, it made more sense to me.

To understand the Ten Commandments, we must read them in context. We’ve already considered the larger context, noting that they don’t receive the law until after their deliverance from Egypt. Now we’ll consider the immediate context. The first statement is not “Thou shalt not,” but rather “I am”—“I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery” (Exodus 20:2). Remember me? I’m the one who rescued your people after 400 years of oppression. This declaration sets the agenda for everything that follows. If we post these commands in public but leave off verse 2, we could easily give the impression that these commands are a burden or form of bondage for those unlucky Israelites. But no, these commands are given to them by a God who rescued them from slavery, a God who has entered into a committed relationship with them, a God who reveals his personal name. Whatever follows must be a dimension of the freedom made possible by these ten boundaries, within which their lives can flourish. The God who saved them is giving them a gift!

COUNTING TO TEN: THE FIRST COMMAND

Counting the Ten Commandments is surprisingly tricky.6 We know there are ten because Exodus 34:28 and Deuteronomy 4:13 both say so. Special notations in the Hebrew text preserve two possible ways of counting them. The history of interpretation has introduced still others. Differences revolve around how to handle the first five and the last two verses. Jewish interpreters often consider the preamble (Exodus 20:2) as the first “Word.” (Since the Bible never refers to these as “Ten Commandments,” but rather “Ten Words,” it’s plausible to have a “word” that is not actually a command.)

Among Christians, there are two main approaches: the Reformed and the Catholic/Lutheran. The Reformed take “no other gods” and “no idols” are the first two commands, whereas Catholics and Lutherans take these together as the first command. They still end up with ten commands because the last command, “Do not covet,” is split in two (note that “do not covet” appears twice).

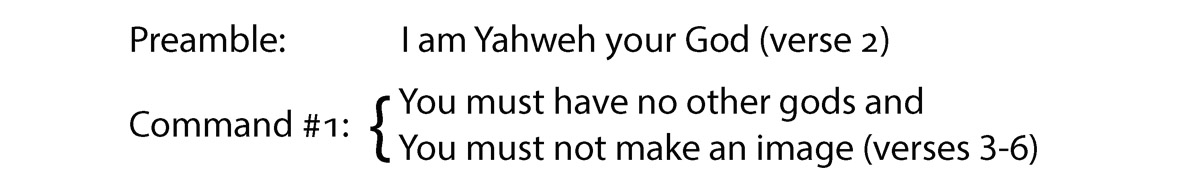

The way we count the commands makes a difference in our interpretation of them. Consider the traditional Reformed view:

Preamble: |

I am Yahweh your God (verse 2) |

Command #1: |

You must have no other gods (verse 3) |

Command #2: |

You must not make an image (verses 4-6) |

The Reformed branch of the church, which counts the command against “images” as its own command, concludes that no images of any deity can ever be made, including Yahweh. The walls of a Reformed church typically contain no pictures of God, Bible characters, or saints.

When I was newly married, I remember a phone conversation with Oma. I mentioned that I was hunting for a nativity scene that we could put out during the Christmas season. I was frustrated because all the options I found were light skinned, blond haired, and blue eyed. She was frustrated for another reason.

“Well,” she chided on the other end of the line, “You should skip it altogether. We are not to make any graven images.”

I was startled. A nativity scene a graven image? With her Dutch Reformed upbringing, any pictures or other representations of God were off-limits, even if they were not an object of worship, and even, apparently, if they were of Jesus. I argued that because Jesus was God-become-human, an artistic depiction of Jesus did not violate this command. Still, Oma wouldn’t budge.

The Catholic church counts the commands differently:

Because the Catholic tradition counts “no other gods” and “no images” as a single command, they read the command against images as a command against images of other gods. As a result, they permit lavish artistic representations of the one true God and great men and women of faith. Show me the inside of your sanctuary, and I’ll tell you how your church counts the commands.

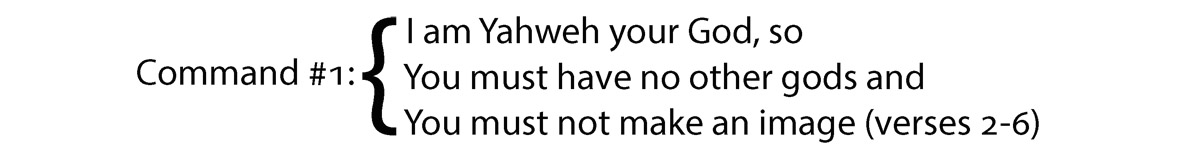

My solution to counting the commands is a combination of all three approaches described above. While most interpreters split Exodus 20:2-6 into two or three separate parts, I count these verses as a single command.

I take the preamble (Exodus 20:2) as part of the first command, providing a rationale for limiting worship to Yahweh: I am the God who set you free, therefore you should worship me alone. Likewise, “no image” belongs together with “no other gods.” I see two reasons for this—one historical and one grammatical. The historical reason is that worship and images went hand in hand in the ancient world. It would be impossible to properly worship a deity without an image of that deity, just as it would be nonsensical to possess an image that you did not worship. The point of images is worship. The means of worship are images.

The point of images is worship. The means of worship are images.

The grammatical reason to read these commands together is found in verse 5: “You shall not bow down to them or worship them.” The recipients of worship are plural, but “image” in the previous line is singular. This prohibition must be continuing the thought of the preceding sentence, a prohibition of other gods (plural). A chiasm (or literary “sandwich” pattern) in Exodus 20:2-6 (or Deuteronomy 5:6-10) reinforces my claim that they should be read together.7

A I am Yahweh your God (verse 2)

B You must have no other gods (verse 3)—plural

C You must not make an image (verse 4)—singular

B′ You must not bow down to them or worship them (verse 5a)—plural

A′ I, Yahweh your God (verse 5b)

The prohibition of images underscores the seriousness of the command to worship only Yahweh. The commands make no effort to convince the Israelites that Yahweh is the only God. Instead, they call Israel to worship only Yahweh. In a sea of options, Yahweh is the only legitimate deity deserving of worship. Rather than monotheism (the existence of one God), the Ten Commandments teach henotheism (the worship of one God). This is not to say that there are other gods, but the Israelites and their neighbors regularly assumed that they existed by seeking divine favor in pagan shrines. The uniqueness of Yahweh is that he calls for exclusive worship.

So that’s the first command: Worship no one but Yahweh. The second command is vitally important for us to understand. There may be a whole lot more at stake with the command not to “take the name of the LORD your God in vain” than you’ve been told.

INVISIBLE TATTOO: THE SECOND COMMAND

I grew up thinking that “taking the Lord’s name in vain” was using “Jesus” or “God” as a swear word. At our house, even “gosh” or “holy cow” cost me a fat twenty-five cents. Both were too irreverent. “Cows aren’t holy!” my dad would say. And he was right, of course. Substitute swear words thinly veil the real thing, and they exhibit the same toxic attitude. After Danny and I got married, I picked up on his habit of saying, “Oh, Lolly!” Here was a winner! It had no resemblance to any of God’s names and had the advantage of sounding quite cheerful. It functioned as the equivalent of “Silly me!” That word worked well until we joined a new Sunday school class at church and met a new friend named . . . you guessed it . . . Lolly. Now we thought we were taking her name in vain and had to come up with an alternative.

Clearly, it’s not advisable to use God’s name as a swear word—dishonoring God in any way is a serious matter, indeed. But after further study, I’m now convinced that most of us have misunderstood the command concerning God’s name, what I call the Name Command. To explain what it really means, we’ll have to go back to the Hebrew and attempt a new translation:

You must not bear (or carry) the name of Yahweh, your God, in vain, for Yahweh will not hold guiltless one who bears (or carries) his name in vain. (Exodus 20:7, author’s translation)

Most translators have decided that this makes little sense. After all, names aren’t lifted or carried, they’re spoken. These interpreters conclude that something must be “assumed” in this statement—something that would have been obvious to the Israelites but is not so obvious to us. And most conclude that the missing something has to do with speaking God’s name, so that the command is prohibiting the spoken use of God’s name in some situation.

Some suggest that we should assume the name is being lifted “on the lips” (i.e., spoken), others suppose that a hand is being lifted to the name (i.e., raising the right hand to swear an oath). They often point to other passages inside and outside of the Bible to make their case for one reading or the other. The problem is that virtually all of these interpreters overlook the closest and most relevant passage of all, one that illuminates this command without adding anything.

The passage is Exodus 28. Buried in the instructions for building a tabernacle (more on that later) is the plan for what the high priest will wear. As the authorized officiant of the holy place, the high priest cannot dress however he wants. Unlike pastors in evangelical churches today who may wear either a suit and tie or jeans and sandals while preaching, the high priest has a specific costume to wear (more on that later, too). His most striking item of clothing is his elaborate apron, woven with gold threads and set with twelve precious stones, each engraved like a seal with the name of one of the twelve tribes. And Moses is told that the high priest is to “bear (or carry) the names of the sons of Israel” as he moves in and out of the tabernacle (Exodus 28:29). Moses’ brother Aaron, who becomes Israel’s first high priest, literally “carries” these tribal names whenever he’s on duty.

SEALS IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST

In the ancient Near East, a common way of declaring ownership of something or of affirming its authenticity was to seal it with a signet ring. Clay tablets often bore the stamp seal of those authorizing their contents or agreeing to its stipulations. Jars of wine or olive oil were sealed shut by means of a blob of clay bearing the authorized seal of a producer, confirming the quality of the product. Seals have even been found bearing the name of a deity. These would have been used in the temple precincts to conduct official business on behalf of the temple.

Some seals were purely pictorial, but others, especially in Israel, were engraved with words. The vast majority of Israelite seals with writing used the letter “L” (called lamed in Hebrew) plus a personal name to indicate the owner of the seal. In this context, the “L” is a preposition that means “belonging to.” The gemstones worn by the high priest are “each engraved like a seal” (Exodus 28:21), and the medallion on his forehead contains the language we would expect to see on a seal: “holy, belonging to Yahweh” (Exodus 28:36, author’s translation). These imply that he is the authorized representative of the tribes to Yahweh as well as the authorized representative of Yahweh to the tribes.

Aaron also wears a name on his forehead—the name “Yahweh.” Tied to his turban is a gold medallion engraved with the words “Holy, belonging to Yahweh.” It’s just two words in Hebrew: qodesh layahweh. The “L” in front of the name Yahweh is the customary way of indicating ownership. If you want to make sure everyone knows that this is your book, you could write your name inside the front cover with an “L” in front of it, and that would be the normal Hebrew way to say it’s yours. With layahweh on his forehead, it’s clear that the high priest is set apart for service to Yahweh. He belongs exclusively to Yahweh. He serves no other.

So what does this have to do with the Name Command? We’ve already noted that most interpreters assume it makes no sense for Israel to be carrying the name of Yahweh, so they look for other possibilities. But right here in close proximity to the Name Command is the high priest, set apart to belong to Yahweh, carrying the names of the twelve tribes. The key to understanding the Name Command is right here!

The twelve gemstones indicate that the high priest represents the entire nation before Yahweh. The medallion on his forehead indicates that he is Yahweh’s authorized representative to the nation. Now think back to the dramatic declaration of Exodus 19, when Israel first arrived at Mount Sinai. There God bestowed titles on his people like treasured possession, kingdom of priests, holy nation. As his treasured possession, Israel’s vocation—the thing they were born to do—is to represent their God to the rest of humanity. They function in priestly ways, mediating between Yahweh and everyone else. They are set apart for his service.

We can see how this connects to the high priest. He is a visual model of the vocation of the entire nation. Just as the high priest represents Yahweh to them, so they represent Yahweh to the nations. By looking at Aaron, every Israelite is reminded of their calling as a nation. Just as he is set apart for service (“holy”), so are they (“a holy nation”). At Sinai, Yahweh claims this nation as his very own and releases them to live out their calling. That calling is to bear Yahweh’s name among the nations, that is, to represent him well.

At Sinai, he warns the people not to bear his name in vain. Keeping this command, then, involves much more than not saying “Oh, Yahweh!” when someone cuts in front of you on the freeway, or a disgruntled “Jesus Christ!” when your team misses a touchdown pass. Keeping the command not to bear Yahweh’s name in vain changes everything about how we live.

If that’s so, how does the Name Command fit in with the rest of the Ten Commandments? Compared to the rest of the commands, doesn’t this one seem a bit too broad to belong on God’s Top Ten?

FORMULA FOR SUCCESS: THE FIRST TWO COMMANDS

One of the key differences between the Ten Commandments and all the other instructions that Yahweh gives at Sinai is the mode of delivery. Moses is the mediator for all the other commands; God speaks to Moses on the mountain, and Moses delivers the message to the people. Not so with the Ten Commandments. When we carefully trace Moses’ movement up and down Mount Sinai, he has just descended the mountain to warn the people one more time not to climb up when God begins speaking. That puts him with the people, who hear the Ten Words directly from God.

If I’m right about how to count the commands and what the first two are saying, then we begin with the two weightiest commands—the ones that set the stage for all the others. Stated positively, they say:

1. Worship only Yahweh.

2. Represent him well.

Together they echo Yahweh’s declaration to the descendants of Jacob in Egypt repeated so often through the Old Testament, especially by the prophets: “I will take you as my own people, and I will be your God” (Exodus 6:7). Jeremiah and Ezekiel repeat this formulaic statement so frequently that it becomes shorthand for covenant renewal: I am yours; you are mine.8 Unlike the gods of other nations, Yahweh could not be represented by a carved image (20:4); instead he was to be represented by the people to whom he had revealed his name (20:7). Since he had claimed them as his own, their words and actions were to reflect his lordship. The first two commands and the covenant formula they express indicate how Israel should fulfill its vocation obligations successfully. They were to worship him exclusively in order to demonstrate his greatness. If they worshiped other gods, his glory would be diminished. They were to be all in, all his.

These two commands bring the covenant relationship into alignment. Yahweh is the only God worthy of worship. Israel must see itself as belonging to him, representing him to the world. To bear his name in vain would be to enter into this covenant relationship with him but to live no differently than the surrounding pagans. Israel’s fate in the succeeding narratives always comes down to breaking these two commands, either failing to worship Yahweh alone or failing to represent him well.

The job of every Israelite is to protect other people’s freedoms.

The rest of the Ten Commandments flow from the covenant formula established by these first two commands, fleshing out what covenant faithfulness looks like in every conceivable area of life: work, family, conflict, marriage, property, and reputation. Daniel Block calls the Ten Commandments a “bill of rights.”9 However, unlike the Bill of Rights in the US Constitution, Block points out that these ten do not focus on a person’s own rights but the rights of one’s neighbor. The job of every Israelite is to protect other people’s freedoms. And it’s done by keeping the Ten Words. Let’s dive into a discussion of the remaining eight.

BILL OF (OTHER PEOPLE’S) RIGHTS

With the first two commands in place, the covenantal “formula for success,” we can explore the other eight commands.

3. Remember the Sabbath Day. The Sabbath command is the one Christians are most likely to think is no longer relevant. But why wouldn’t we want it? The Sabbath command protects the entire household’s right to rest, ensuring a rhythm of sustainable living. No one (including animals!) in this new society is to slave away 24/7. Slavery is a thing of the past. Each Sabbath is an expression of trust in Yahweh’s provision, put into practice first in the wilderness with the collection of manna six days a week. It’s not just the master of the house who gets a day of rest, while everyone else waits on him. Rather, the entire household is free to participate in this rhythm of grace.

Sabbath requires advance planning. Meals prepared ahead, house in order, chores done, homework complete. Sabbath is not simply ceasing from labor, but actually enjoying its results from the other six days. In Exodus 20, God’s creative work is the model for Israel’s Sabbath. Like a king who rests on his throne after enemies have been defeated and the realm is at peace, so Yahweh rests after he brings order to the universe. It’s not that he’s tired and needs a nap. Rather, he can sit back and enjoy the fruit of his success.

4. Honor your father and your mother. We tend to think of this command as the one for children, but nothing signals a change of audience. Adults must honor their parents too. This is especially critical in a culture with multigenerational households, such as ancient Israel. A friend of mine is engaged in a daily adventure following this command. He and his wife and their four children live in a modest house with both of their mothers and one of their grandmothers. Though having four mothers from three generations in one household is a challenge, to say the least, this family is convinced that they must find ways to honor each one.10

Protecting parents’ honor ensures that the Sinai covenant will be passed from generation to generation. The New Testament calls this “the first commandment with a promise” (Ephesians 6:2): “so that you may live long in the land the LORD your God is giving you” (Exodus 20:12). But what does this mean? That individuals will live to a ripe old age? Not necessarily. We can all think of godly, parent-honoring people who have died young. No, this command doesn’t promise old age. It promises that an entire nation will continue to enjoy living in the land as long as the covenant is kept. Discarding their parents’ faith would have disastrous consequences, making the people vulnerable to exile and perhaps death.

The remaining commands all contribute to a community characterized by mutual trust. If every individual covenant member ensures the protection of his neighbor’s life, spouse, property, and reputation, then everyone will have space to live and flourish.

5. You must not murder. This command protects the neighbor’s right to life and to a fair trial in the case of a dispute. Individual Israelites may not take matters into their own hands, disregarding those with God-given authority to settle disagreements. Tempers do not guard justice. Revenge has no place in the covenant community.

6. You must not commit adultery. Each neighbor has a right to a marriage free from competition. For the covenant community to flourish, relationships between neighbors (and spouses!) must be built on mutual trust. Every man’s job is to protect his neighbor’s marriage and his neighbor’s wife, rather than preying on her.

Sexual intimacy is reserved for marriage because marriage is a reflection of the covenant with Yahweh. In both, two enter into an exclusive commitment: “I am yours; you are mine.” For marriage to work as God designed, both parties must give themselves wholly to each other and to no one else.

7. You must not steal. Every Israelite has a right to personal property, free from the greed of the neighbor. As with marriage, the protection of a neighbor’s property is everyone’s business. “Neighborhood watch” is a very old idea, and it’s biblical. By taking what’s yours, I demonstrate a lack of gratitude and a lack of trust in God to provide for my needs.

8. You must not give false testimony. In an age without DNA testing, fingerprinting, video surveillance, and lie detector tests, a person’s word held a great deal of weight. It was crucial to the maintenance of a just society that no one wrongly implicate a fellow Israelite. Each person’s reputation depended on truth. Slander would eat away at the community like acid. Even with all of our technological advances, false accusation still deals a harsh blow, sometimes with devastating consequences. Your word against my word—who is right?

9-10. You must not covet your neighbor’s house, and you must not covet your neighbor’s wife or any other household member. The Ten Commandments close with two surprising commands that are totally unenforceable. How can anyone prove that someone craved their neighbor’s house or wife when lust is a heart condition? The internal nature of these commands hints at the function of the entire law. This is not legislation in a modern sense, but character formation. These instructions paint an ideal picture of a covenant-keeping Israelite, including both outward behavior and inward motivation.

A friend in college posted these words on her dorm-room wall: “Happy is the woman who wants what she has.” It’s true. Contentment does not lie in gaining more, but in cultivating gratitude for what we already have. Another friend posed the question, “What if we awoke tomorrow with only what we thanked God for today?” To crave what we lack makes us bitter and sullen. It builds a wall between us and the God who has given us so much.

And that’s it. Those are God’s Top Ten. The stipulations of the covenant—the source or seed of all the rest of his instructions at Sinai.

These first words the Israelites hear directly from Yahweh make quite an impression on them. To put it lightly, they are intimidated. “When the people saw the thunder and lightning and heard the trumpet and saw the mountain in smoke, they trembled with fear” (Exodus 20:18). Given the drama of Yahweh’s appearance, the people are glad to have Moses as a mediator. They insist, “Speak to us yourself and we will listen. But do not have God speak to us or we will die” (Exodus 20:19).

Moses reassures them in an odd way. First he says, “Do not be afraid” (Exodus 20:20). But he follows this immediately by letting them know that their fear is part of God’s goal: “God has come to test you, so that the fear of God will be with you to keep you from sinning” (Exodus 20:20). So which is right? To fear or not to fear?

In his commentary on Exodus, Peter Enns paraphrases it this way: “Do not be afraid. God is giving you a taste of himself so that this memory will stick with you to keep you from sinning.”11 In other words, you can trust the God who has thundered on the mountain. He is not out to get you. Yes, he’s calling you to a high standard of behavior. He expects a lot of you. But he wants you to succeed at covenant faithfulness. He’s for you. That’s why he’s letting you see how awesome he is.

If anything, we learn in Exodus 20 that the law is not an end in itself. It is Israel’s means of knowing Yahweh, and of living out their vocation in the world. When Moses climbs back up the mountain, God gives him a much longer list of instructions. We quickly discover that the Ten Commandments are not the final word.

DIGGING DEEPER

Daniel I. Block. How I Love Your Torah, O LORD!: Studies in the Book of Deuteronomy. Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2011. Chapters 2 and 3.

Daniel I. Block. The Gospel According to Moses: Theological and Ethical Reflections on the Book of Deuteronomy. Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2012. Chapters 4, 5, and 8.

Carmen Joy Imes. Bearing YHWH’s Name at Sinai: A Reexamination of the Name Command of the Decalogue. BBRSup 19. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 2018.

Michael Harrison Kibbe. Godly Fear or Ungodly Failure?: Hebrews 12 and the Sinai Theophanies. ZNTW 216. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2016.

*Jan Milič Lochman. Signposts to Freedom: The Ten Commandments and Christian Ethics. Translated by David Lewis. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2006.

*Sandra L. Richter. The Epic of Eden: A Christian Entry into the Old Testament. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008.

Related video from The Bible Project: “Law.”