11

Going the Distance

The span of time between an initial concept and a theatrical release can be years or even decades. And that’s if the concept ever becomes a film. Once a screenwriter decides to put an idea down on paper, he or she begins an odyssey that could as easily end in jubilation as heartbreak—every time some lucky soul steps into the global spotlight and claims an Academy Award, thousands of writers are left asking why their dreams haven’t come true. And yet the next morning, those same writers start anew, hoping that maybe this time, they will craft a classic.

Why do some writers win the Hollywood game, while others do not? And why do so many people chase the dream given the long odds against success? The answers to both questions are the same. Screenwriters do what they do because they love their craft. Because neither artistic nor financial success is guaranteed, creative fulfillment is the only tangible goal that screenwriters can pursue. The satisfaction of shaping an effective screen story is as potent for a veteran as it is for a beginner. What happens after the work is done is anyone’s guess, so writers must savor precious moments of accomplishment.

The most contented screenwriters are those whose passion for their work never dims, because the intensity with which those artists infuse every page translates to buyers and, ultimately, to audiences. As Paul Schrader, Ron Shelton, Gerald DiPego, and Justin Zackham explain in the remarkable stories that open this final chapter, the desire to express intensely personal ideas can beget unexpected triumphs. Yet the same passion that leads to inspiration can lead to inertia, when the hope of achieving greatness becomes the ambition to attain flawlessness. No matter how romantic the idea of writing the perfect screenplay may be, even some of the artists who have come closest to reaching that pinnacle say that consciously striving for perfection is folly.

So if success is uncertain and perfection is unattainable, must screenwriters console themselves with the private pleasure that Zak Penn calls “an artisan’s joy of doing your craft well”? Not always. For as the screenwriters whose inspiring words end this chapter explain, the most powerful gratification any storyteller can experience is the knowledge that his or her work has touched others.

The Screenplay’s the Thing

PAUL SCHRADER: Taxi Driver came out of me like an animal. I was in this bad space, and I ended up at the hospital with an ulcer, and I’d been living in my car. The metaphor of the taxi—this iron coffin floating through the city, with this person locked inside who seems to be surrounded by people, but is in fact desperately alone—I realized the taxicab was the metaphor for loneliness. I had a metaphor, I had a character, and then there was just the matter of creating the plot. It’s a very simple plot. He desires a woman he cannot have, he doesn’t desire a woman he can have, he fails to kill the father figure of the one, he kills the father figure of the other, and becomes a hero by ironic coincidence. That’s essentially the story. It’s really just a kind of fetid character study.

Taxi Driver didn’t really find a buyer. The script wasn’t actually sold in that way. I was reviewing something that Brian De Palma had done. It turned out he was a chess player, so we were playing chess, and I told him I had written the script. He read it and liked it. In fact, he wanted to do it at that time. He gave it to the producers Michael and Julia Phillips. They wanted to do it. And then Julia and I saw an early version of Mean Streets, and we really felt that Marty Scorsese and Bobby De Niro should do Taxi Driver. Marty wanted to do it, so we made an arrangement with Brian, and then we had the group of us together—Michael and Julia, De Niro and myself, and Scorsese—and, of course, we could not get it made.

But we all had a blast of good luck. I sold The Yakuza. Michael and Julia won the Oscar for The Sting. Bobby won the Oscar for Godfather II. And Marty had a success with Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Suddenly this group of people who couldn’t get it financed did get it financed, albeit as a kind of charity job from David Begelman at Columbia. It would not have been financed today. It was a studio system where they would occasionally make a film like this just to keep a diversified slate.

RON SHELTON: Bull Durham was a first draft. Only one draft has ever been written. I wrote it in about ten weeks. I wrote it without an outline, without any notion of where I was going. I went down to the Carolinas and drove around to see the minor-league ballparks. I wanted to see if that world had changed since I had played in the minor leagues years earlier, and I discovered it hadn’t. It was as unglamorous as when I played: Women came to the ballpark, these players were heroes in these small towns, everybody was afraid of being fired, and these dreams were probably never gonna be realized for most of these guys.

I drove from Durham down to Asheville, North Carolina. I drove on the back roads, and I had a little mini-cassette recorder. I said, “Well, if this woman tells the story, what would the opening line be?” And I wrote, over a 140-mile drive, “I believe in the church of baseball.” I’d drive five miles. “I’ve worshipped all the major religions, and most of the minor ones.” I’d pull over for a hamburger, keep going. By the time I got to Asheville, I had dictated that opening two-page monologue.

A couple months later, I got back and I pulled that out, and I transcribed it. I gave her the name Annie because of “Baseball Annie,” and I had a book of matches from the Savoy Bar that I’d been at. That was Annie Savoy. I just kept writing, and I wrote the whole script. Gloriously, the producer read it and said something that producers are incapable of saying these days. He said, “I want to shoot it now,” as opposed to, “I’ll give you my notes next week.” A few weeks later, we were shooting.

GERALD DiPEGO: The Forgotten was the only screenplay of mine that ever actually came from a dream. I woke up with a certain core image in my mind—a mother-father-and-son photograph, and while I was staring at the photograph, the son disappeared from the photograph. It was so powerful it woke me up. It was probably six o’clock, and I just started filling in “What could that mean? What kind of story could that be?” And probably about eight o’clock, I woke up my wife and said, “Listen to this,” and I told her the possibilities.

My usual way is to think it through for three or four weeks—kind of see the movie in my head—and then start writing. So about three months from the time I dreamed it, I had it on my agent’s desk. He was very excited by the concept, and he said, “We’re gonna go out wide next week, but before we go out wide, I know Joe Roth is looking for another story for Revolution Studios, so I want to give it to him and see if he wants to make a fast move to take it off the market.”

Joe Roth called back a few hours later, and the offer was made.

JUSTIN ZACKHAM: I got to a point where I was actually getting kind of disgusted with myself, because I wasn’t writing much, I wasn’t writing well, and I had just sort of fallen into this laconic malaise. One day, I woke up and I was lying in bed thinking, “I gotta get my shit together.” And I got a piece of paper and I wrote at the top: “Justin’s list of things to do before he kicks the bucket: Get a film made at a major studio. Find the perfect woman, convince her that I’m not a schmuck, get her to marry me.” I tacked it up on the wall, and then gradually it sort of faded into the wallpaper. About two years passed.

I was in a bookstore one day, and I don’t know what happened. It was just like, “Pow!” I sat down and I tore blank pages out of a couple books, and I just started writing. I wrote the whole story of The Bucket List. Ultimately the story is these two guys each have their own list of things that they wanna do with the short time they have left, but the one thing that’s not on either of their lists that they’re both missing is a true friend. They find that, and that’s what the movie’s about.

I wrote it very quickly, just in a few weeks. I gave it to my agents and they said, “This is great, but nobody’s gonna buy this.”

Normally your agents will send a screenplay to one producer with a deal at each studio. We sent it to fifty producers, and forty-eight of them said no. Two of them said, “We don’t think anyone’s gonna buy it, but we think it’s really good, so we’d like to give it to studios.” All the studios said no, but one of the producers said, “I really think if you get this in the right hands, this could get done.” They said, “Given any director in the world who you’d want to shoot this, who would it be?” I was like, “Rob Reiner’s made some pretty good movies.”

So they sent to script to his agents at CAA, and three days later he calls up: “Hello? I’ve read thirteen pages of this thing, and if it’s okay with you, this would be my next movie.” He and I worked on the script for probably a total of six months, off and on.

I had written the movie with Morgan Freeman’s voice in my head. Rob got Morgan’s number and called him up and said, “Hey, I’ve got this script you should read.” A week later, Morgan said yes. You know, Rob Reiner already said yes, and now I get Morgan Freeman—it was just ridiculous. We’d been talking about who would play the other character, and Rob and I weren’t sure. Morgan said, “Jack Nicholson and I have talked about always wanting to work together, and if I had a bucket list, working with Jack would be on that list.” What are you gonna say to that?

Rob had worked with Jack on A Few Good Men, and obviously that turned out pretty good, so we sent the script to Jack, and a week later, he called: “Yeah, I’ll do it.” I had separated myself from any notion of reality at that point, and I still haven’t come down.

The greatest twenty-four hours of my life was September 3, 2006. I got married in New York. The next morning, I woke up at five, kissed her good-bye, got on the plane, flew to Los Angeles, and drove up to Jack’s house. I walked in and sat down at his dining-room table, and there was me, Morgan Freeman, Rob Reiner, and Jack Nicholson. Rob started to read the stage direction, and the minute the two actors talked to each other…goosebumps. It was absolutely the most indescribable feeling. It was perfect.

Crazily enough, it was a year to the day after I went out with the script that we started principal photography—and that just doesn’t happen. That will never happen again to me.

Justin Zackham

The Perfect Script

STEPHEN SUSCO: Only once in my career have I written a script and someone just gave me the check for a rewrite and said, “We don’t want you to do the rewrite, we think it’s perfect.” And then a year a later, they decided it wasn’t, so….

DOUG ATCHISON: I wrote fourteen drafts of Akeelah and the Bee before we shot it. The third draft won the Nicholl Fellowship. I’m glad I didn’t shoot that draft, because that draft was not ready. I rewrote it again and again and again. We were rewriting in rehearsal, and I was changing lines on the set, and we were rewriting in editing. You can always make it better.

ANTWONE FISHER: I wrote forty-one drafts of my story before the producer, Todd Black, felt like he could give it to Fox. The executives gave me a lot of notes, and then Denzel and Todd and I worked on it for almost six years. I must have written over a hundred drafts of that story.

BILLY RAY: Chinatown took seventeen drafts, and none of us is as good as Robert Towne. Amadeus, I think, took forty-six, and none of us is as good as Peter Shaffer. So all that means is that after the previous forty-five drafts of Amadeus, someone said, “Peter, you can do better.” I’m sure it pissed him off and hurt his feelings, but he kept writing—and he wound up with one of the best movies ever.

SHANE BLACK: I play Tetris obsessively with scripts, and realize that I still have nothing resembling a finished draft, because I’m still stuffing ideas in and hoping that these three things will come together to form one hybrid. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang started as a romantic comedy. Then it was a straight comedy. Then I added the detective character, and it became this dark thriller. Then I went back in time to the forties and tried to get some of these old-time detective pulp novels involved, and say everything I had to say about that. By the end, it’s sort of this mishmash. It’s a pulp-style homage, fairy-tale, retro, film-noir, comedy, “kids in the big city,” Capraesque murder tragedy. You know, it’s everything stuffed together. For some reason, that one worked—but you can play that game forever and never get anything done.

JONATHAN LEMKIN: I’m a better writer now than I was three years ago, a better writer now than I was ten years ago. But I can’t beat myself up about the fact that the work I’m doing today is not the equivalent of the best work someone else did at the peak of their career. You get up each morning, and you do the best work you can do that day. To strive for perfection is a waste of your energy.

DANIEL PYNE: Look at your writing as a process, rather than an end in itself. I think once you stop getting better, you’re dead—you might as well quit. The ability to expand and improve is something that I find in writers I know and admire. It’s a quality that helps them have careers that lasts decades, rather than years.

JOE FORTE: There’s so much to master, from character to dialogue to plot to theme to concept. It’s this machine with a lot of levers and buttons, and it takes a long time to master all those things, and to play them like a pipe organ—well, all at the same time. The more of those pieces you play well, the more you start to get a response to your material, because many things are working in your material at once. Mastering all those levers to get character up here and plot up here and concept up here and marketability up here—to me, that’s the Holy Grail. I think that’s what we all aspire to.

FRANK DARABONT: We spend our lives pursuing the chimera of perfection. It’s an elusive and ephemeral idea. Is there a perfect script? There are some that get awfully close. The Sting has been cited. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid has been cited. I would make an argument for Casablanca and It’s a Wonderful Life and Double Indemnity. These are the best of what we do. Perfection? I think it probably should remain the mirage that you keep chasing, because if you ever achieve it, then you might as well just give up. You might as well throw in the towel and say, “Okay, I’m done! Put me on the stretcher and take me to the old folks’ home.” I think you gotta keep trying for that.

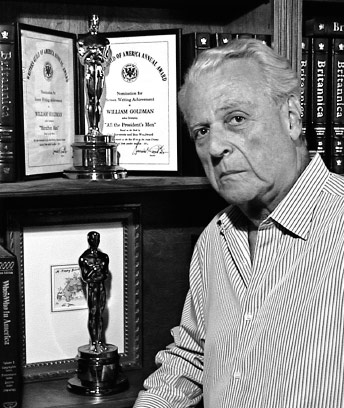

WILLIAM GOLDMAN: I don’t know what it means, a perfect script. I think you just wanna basically try to figure out the fuckin’ story, and stay in the story as long as you can and as closely as you can, and end it. I think when you start telling yourself, “I wanna write a perfect thing,” all you’re gonna do is castrate yourself, and get into deeper and deeper trouble. It’s hard to do anyway. It’s no fun going into your pit every day and trying to figure out how to get two or three or five pages. Some days you don’t do anything. Then if you have two crappy days in a row, you’re really in deep shit. You just wanna get it done, and you pray someone will like it.

DAVID S. WARD: I don’t think there’s any such thing as a perfect script. When people say that The Sting is a perfect script, it’s nice to have people say that, but it’s also slightly embarrassing to me—because I just don’t think there’s a perfect anything. You know, the world is imperfect. Everyone strives for perfection, but ultimately we all settle for the best we can do. I think that’s basically the nature of life.

I’ve been at this a long time. After a while, you just know that even though certain things are not going to see the light of day, if you keep working, and if you keep doing things that you like, and if you keep doing a good job, that sooner or later there are things that will see the light of day, that will get made, and that hopefully someone will go and see. If you love movies, and you love doing them, then that always keeps you going.

Making Magic

BILLY RAY: This is a last-laugh business. If you can survive as people are kicking you in the head, eventually their leg will get tired. They will want to start kicking someone else. If you’re still there and can pull yourself up to your feet, you get the last laugh.

ROBERT MARK KAMEN: If you got craft, you got game. If you got game, you can write your way in and out of anything. Writing is the best gig in the whole business, as far as I’m concerned. It’s the only job where you don’t have to wait for someone to tell you what you do. You just sit down and make shit up.

JOHN CARPENTER: It’s a great way to make a living, in the sense that they pay you a bunch of money, and the smart writer can kind of ignore everything until two weeks before you have to deliver it. If you’ve written a good outline, then just bang it out and turn it in—and they pay you more money. It’s not a bad way to go.

LARRY COHEN: To me, the best present anybody ever gave me is a ream of blank paper. I look at that blank paper, and I say, “I wanna go and fill it up.” You know, everybody talks about the writer being the low man on the totem pole out here. That’s nonsense. The director doesn’t get paid if he doesn’t make the picture. The actors don’t get paid if they don’t come to work. I get paid whether they make the movie or not. If the picture comes out and it doesn’t do well, nobody phones me and says, “Hey, Larry, could you send us back of some of that money?” Never. You get to keep it all. I can write five, six, seven, eight scripts a year. A director can probably only make one or two pictures a year at the most. So even though directors usually get more money, we get more volume, and we don’t even have to leave the house if we don’t want to. They’re out there freezin’ their ass off up in the snow, and I’m sittin’ by the swimming pool. Who’s got the better job?

GUINEVERE TURNER: On Go Fish, we were sort of shooting it and writing it at the same time, and I wrote this scene where one of the lesbians has sex with a man, and all of her lesbian friends come down on her for it. The crew, who were all lesbians, read that scene I had just written, and they said, “If you put this in the movie, we’re all quitting.” I turned to Rose, the director and cowriter, and I said, “Wow, that so means it needs to be in the movie. The fact that all of these women are so messed up about it means that it’s powerful.” I was like, “This is gonna be a great movie, and people are gonna talk about it, and get all riled up about it.” That was when I was like, “Hmm, maybe short fiction in the New Yorker isn’t my calling.”

NAOMI FONER: As I said, I entered this process to change people’s ideas about things. I know some things that some people don’t know, and vice versa. What small things I know that I can show other people, those are the possibilities. Running on Empty is an interesting example. The scene that people respond to most is that one between Christine Lahti and her father, where they connect. It’s not because anybody knows what it’s like to be underground. It’s not because most people miss seeing their parents for fifteen years. It’s because at some moment, most people understand what it’s like to be a parent because they become one. And Running on Empty isn’t really so much a movie about radicals, although that’s the surface of it, as it is about parents learning to love enough to let their kids go. Everybody has to have that moment, which, if done successfully, is actually the culmination of what happens between parents and children: They leave. So what people are responding to is universal. And when people respond to the universal in your work, it’s incredibly satisfying. You feel like you’ve done your job well, and it sustains you.

Naomi Foner

ZAK PENN: Even on X-Men: The Last Stand, going to the opening-night show at Mann’s Chinese Theatre and watching a crowd totally love the movie—that’s incredibly thrilling. You feel, for a moment, like a rock star. I remember coming up with the idea for the opening scene of The Last Stand and pitching it to my partner, Simon Kinberg, and him saying, “Wow, that’s good, we should do that.” There’s, like, a joy that comes out of that. It’s an artisan’s joy of doing your craft well.

WILLIAM GOLDMAN: I always feel that when a movie sucks, it’s my fault. I mean, I could blame the director or the actors, but I usually feel if a movie is no good, then it’s something in the script—something in the storytelling I did—that didn’t hold. It was just bad. It was wrong.

The lesson is you don’t know what you’re doing. You hope you do, but you don’t. The thing that’s so awful about being a screenwriter is you do the best you can, and you have no idea if the story you’ve chosen is gonna hold for an audience. It’s a crapshoot. There’s no logic to it, there never has been, and there never will be.

For me, the two greatest screenwriters are Billy Wilder and Ingmar Bergman. They did just amazing work. They also did shit. Even Bergman had stuff that just didn’t work. It just lay there. He didn’t say, from his island, “Well, I’m gonna make a crappy movie now.” It just didn’t work. Look at Billy Wilder’s career. It’s an amazing career, but in the midst of those fabulous movies, there’s stuff that isn’t so fabulous.

Everybody has turds, but they don’t say, “Oh, boy, I’m gonna make a turd of a movie today. It’s really gonna be great. I’ll lose the studio $80 million. I’m just so happy.” No, you don’t do that.

William Goldman

RON SHELTON: At the end of the day, you turn out the lights, you shine light through emulsion, and people either are engaged or they’re not. That’s probably the most terrifying moment, because it all started with page one: “EXT. THE PLAINS OF EAST TEXAS—DAY.” And either a year or ten later, the curtains are gonna part, and you’re gonna see if an audience cares about this journey that starts on the plains of East Texas—and you’ve been on that journey all these years.

JUSTIN ZACKHAM: We finished The Bucket List and had a test screening in Pasadena. I sat in the back, and the audience laughed throughout the whole thing, cried for the entire third act, and while they were crying they were laughing at the same time. Those guys up there on the screen were saying my words, and the audience was reacting the way they were supposed to react. It was just an amazing feeling.

At the end of the screening, Alan Horn, who’s the chairman of Warner Bros., came over. I was standing with a couple of the producers, and they said, “So what’d you think?” And the first words out of his mouth were, “Wow, what a great script.” And they said, “Oh, well, this is Justin. He wrote it.” And he was like, “It was really great to meet you.” And you know, a moment like that—the head of a studio, the first words out of his mouth, recognizing what a great script—you stay positive from that.

When you get compliments on your writing, you have to squirrel those things away and pull them out on those dark days, when you’re sitting there pulling the hair off the top of your head because you can’t get this scene to play, or whatever it is.

It’s very easy to get cynical, to harp on all the bad stuff. But you have to allow yourself to feel good. Don’t let the highs get too high, but don’t let the lows get too low. If you can operate on a wavelength that’s somewhat in the middle between the two, you’re gonna be okay, because that’s pretty much where most of the truth lies anyway.

BRUCE JOEL RUBIN: My Life did not have a huge following. I don’t know the actual numbers of people who saw the film, but the power of the connection between those who did and me was enormous.

The reviews were beyond-belief cruel. The studio sends you a packet of all the reviews from your movie across the country, and I started reading those reviews, and one after another was a below-the-belt punch. I was on the floor for months after that movie came out. I thought it was the biggest failure I had ever been involved in.

And then, about nine months later, a woman comes up to me at a party, and she says, “My husband died of cancer a year ago, and my son couldn’t speak about it. He was twelve. He’s now thirteen. I now have cancer, and I have six months to live.”

I’m just kind of reeling as she’s saying this.

She says, “About a week or two after your movie came out, my son and I went to see it. When the movie was over, we went back home, and he was sobbing. He crawled into my lap, and he and I had the dialogue that I needed to have to leave this world. It would not have happened without your movie, so thank you.”

Something happened to me at that moment: I realized I made the movie for her. And it was enough.

FRANK DARABONT: The slow build of The Shawshank Redemption was really quite remarkable for me, because it was not immediately embraced.

The audiences who saw it loved it from the start. I don’t think, to this day, Castle Rock has had better test-screening scores than Shawshank. We knew we had a movie that people really, really loved. But it turned out we had a movie that people really, really didn’t wanna see. You know, loving a movie is conditional upon leaving the house, going to a theater, buying a ticket, and walking into that particular movie. It was tremendously frustrating to be so well received, and so well reviewed—and so poorly attended. You sit there and you go, “What does it take to get people to see it?”

In our case, what it took were the seven Academy Award nominations we got that year, including Best Picture. That brought a lot of attention to the movie. Shawshank came out in 1994. We wound up being the most-rented video of 1995, and the thing I credit for that is the fact that in 1995, when people were watching the Academy Awards, Shawshank got mentioned seven times during the course of the broadcast. I was there, obviously, and even in the auditorium, every time they mentioned Shawshank, you’d hear this muttering in the theater: “What?” “Huh?” “That got nominated for something?”

People started checking it out on video, and Ted Turner started airing it on his stations every five minutes. People discovered it, I think, the way they discovered It’s a Wonderful Life or Casablanca or The Wizard of Oz. Not that I’m comparing my movie to those—I lack the hubris for that—but those movies didn’t do well either when they first came out. They started airing once or twice a year on television, and entire generations got to know them, and they developed the reputations that had eluded them prior to that.

Shawshank kinda had the same thing. People discovered the film, and they discovered—much to their surprise, and to my delight—that they love the movie. People really, really dig it. More than that, it means a lot to some people—there are some people for whom it’s more than a movie. I take great satisfaction in that, because I have a few movies that, for me, were more than a movie when I was growing up.

Maybe I’ll never make another thing that people love on that level, and that’s fine by me. Because at least I’ve had one.

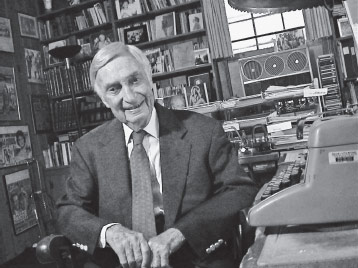

The Veteran’s Perspective: Melville Shavelson

Melville Shavelson

The career of Melville Shavelson spanned several eras. He made his name writing gags for Bob Hope, and notched his first screen credit on Hope’s The Princess and the Pirate (1944). Shavelson later earned Oscar nominations for cowriting The Seven Little Foys (1955) and Houseboat (1958), both of which he directed. He was involved in more than three dozen projects for film and television as a writer, producer, or director. In 1984, Shavelson received the Laurel Award for lifetime achievement in screenwriting from the Writers Guild of America. The organization, which Shavelson led during three terms as president, renamed its research facility the Writers Guild Foundation Shavelson-Webb Library in 2005. Born April 1, 1917, Melville Shavelson died on August 8, 2007, the day after he was interviewed for this book.

What About Bob?

I am a writer by choice, a producer through necessity, and a director in self-defense. I learned that being able to control all of those areas was a way to get your ideas on the screen.

I started writing in New York. My cousin worked for Milt Josefsberg, who later became one of the top comedy writers. My cousin was going over to the ILS news agency, and he said, “Do you want my job?” I went up to Milt and he said to me, “You get the same salary that I paid your cousin, twelve dollars a week,” which was not too bad in those days. He said, “Now I’m goin’ to the beach.” He came back late in the afternoon, and I handed him twenty pages of jokes. He said, “Where did you get these jokes?” I said, “I wrote ’em while you were getting that sunburn.” He said, “Your salary is now fifteen dollars a week,” which is the biggest compliment I was ever paid in my career.

I came up in the days of radio comedy. Radio humor was usually constructed in a room with a lot of people pitching in, and you got used to working together with a lot of other people. That became very valuable to me because I found a fellow named Jack Rose, who became my partner.

I came out to Hollywood originally with Bob Hope, because I worked on his radio show. Bob would give us the screenplay of the movie he was working on and say, “If you punch this up, I get $5,000 from the studio that you can have.” Later, when I went to work for Sam Goldwyn on The Princess and the Pirate, Goldwyn said, “Well, now I have one of his writers working on the movie—I won’t have to pay the son of a bitch that $10,000 anymore.” I found out how Bob became the billionaire he was.

Jack Rose and I located the story for The Seven Little Foys. We went up to Bob’s house and started telling the story, and Bob said, “That sounds like a good story. I think I will do that.” And I said, “You can’t.” And he said, “Why not?” And I said, “If you want the story, Jack Rose has to produce it and I have to direct it. He’s never produced a picture, and I’ve never directed anything in my life.” Bob said, “You caught me at the right time. My last picture was so lousy, you can’t do any worse.”

That’s how I became a director.

Me and My Shadow

Cast a Giant Shadow was the story of Colonel Mickey Marcus, the American colonel who helped lead the Israeli army to its 1948 victory. I took it to every studio in Hollywood, and all the executives turned it down, saying they’d already donated to the United Jewish Appeal, and they didn’t have to make a movie about it. Besides, who wanted to see a film about a Jewish general?

So I went to the least likely candidate. John Wayne had the reputation of being the most conservative guy in Hollywood, so I brought him the story. When I finished, Wayne got to his feet and took six and a half months to light his cigarette. I could see my future disappearing. Then he exhaled and said, “That’s the most American story I ever heard. It’s about an American officer who helped a little country get its independence, and he gave his life to do it. What could be your problem?”

I told him that every executive in Hollywood had turned it down. He said, “I can’t play Mickey Marcus. I’m much too old, and besides, who would ever believe I was circumcised?” I said all I wanted him to do is to play an American general in the picture, and then the whole picture would become gentile by association. He smiled, and I took his smile around to the studios in Hollywood. Once I did that, I got Kirk Douglas, Frank Sinatra, Yul Brynner, and Angie Dickinson. When I announced the cast, somebody said, “With that cast, you could make the telephone book and make a lot of money.”

My mistake was I made my script instead of a telephone book. The picture is still in the red, and I’m still paying it off. I don’t think it will ever succeed, but I’m glad I tried.

I had a lot of difficulty with Kirk. Long after the picture was out, Kirk finally wrote me a letter, and in the letter he says, “I think it was a good picture. It could have been better if I’d paid more attention to you. Love and kisses, Kirk Douglas.” There aren’t many of those letters around, but this one is here on my wall.

The Road to Rejection

I wouldn’t know how you would get a picture made today, because it’s a different world. It’s almost impossible to find a story in a film that is being made today, because they don’t believe in stories anymore. It’s obvious that the inmates control the asylum. The actors are controlling a great deal of what gets to the screen. The difference today is that the costs are astronomical, but so are the rewards. In the old days, if you could make a movie for less than $1 million, you had a chance. Today, you can’t even get an ad campaign for anywhere less than $100 million. My compliments to everybody today who’s managed to get a film made.

In the studio era, usually you tried to locate a star in advance, and get their approval of what you’re doing, and sell it partly on the basis of their name. You always had to submit an outline of your story. And then if you went beyond that, you had to submit a screenplay. It was a gradual process, and it was different in every case. There was always a different reason why you sold something. A large part of it was writing and being rejected, so you’d learn what would sell and what wouldn’t sell.

The reason why a script got made was not necessarily connected with its quality, but it may have been timing, and it may have been knowing somebody—and also your ability to pitch it, because a lot of the selling was done verbally.

Don Hartman was a wonderful friend. He and his partner, Frank Butler, wrote the Road pictures for Hope and Bing Crosby. They pitched a story to Buddy de Silva at Paramount, and de Silva said, “Okay, that’s a good story. Go home and start writing it.” They went home. Don had been on his feet pitching, and he couldn’t remember a word of what he said. So they went back to see Buddy, and they said, “We don’t know how to tell you this, but I got up and started pitching that story, and you kept laughing and laughing and laughing. I don’t remember what I said. What were you laughing at?” And Buddy said, “I was laughing that it was such a lousy story, you guys were gonna have to break your ass to get a screenplay out of it.” That story became The Road to Moscow, which never got made.

All I can say is, I’ve got a shelf of films that I’ve written, directed, produced, or whatever, and a much larger shelf of films that have never been made. Those scripts are usually a lot better than the ones that got made. If anybody wants to buy one, they’re all available.