Pot Limit Omaha (PLO) is the new game of choice among the action junkies. As the NLH games got tougher, players branched out and looked for weaker spots. They found them at the PLO tables, and ever since, the game has grown steadily in popularity. Many of the skills that make you a winning No Limit Hold’em player translate well into your PLO game.

However, there are many important, nonintuitive differences. See, PLO is still in its infancy, much like NLH was ten years ago. So the fundamentals in this section should give you the tools to beat a $5–$10 game. At stakes higher than that, you’ll have to wait for Galfond or Dwan to write a book—I’m waiting for that myself.

![]()

Among popular poker variants, PLO is the most fun and action packed. The game is played in the same sequence as Hold’em. Hole cards dealt, round of betting. Three-card flop, round of betting. Turn, bet. River, bet. Showdown. There are two essential differences between No Limit Hold’em and PLO:

![]() Each player gets four hole cards and has to use two, and exactly two, of those four—three from the board, two from the hand.

Each player gets four hole cards and has to use two, and exactly two, of those four—three from the board, two from the hand.

![]() Pot Limit Omaha is “Pot Limit,” not “No Limit.” Players are limited to the size of the pot with each raise.

Pot Limit Omaha is “Pot Limit,” not “No Limit.” Players are limited to the size of the pot with each raise.

Having two more hole cards in each hand drives action to an unprecedented level by effectively giving players six different Hold’em hands to play at the same time. As a result, pre-flop hand values are much closer in Omaha than in Hold’em. Many more hands are playable in Omaha, leading to tons of multi-way pots. With so many possibilities and close hand values, the variance for PLO skyrockets. If you have a hard time handling the swings of NLH, stay away from PLO.

In Pot-Limit betting, if you’re going to raise, that raise is limited to the size of the pot. For example, in a $5–$10 game with a $5 small blind and a $10 big blind, a “pot-size raise” is to $35:

$5 small blind

$10 big blind

$10 my “call” of the big blind

$25 subtotal size of pot before I raise

$25 raise

$35 maximum pot-size raise

Now, say my opponent raises the pot and the action is folded to my big blind and I want to raise the maximum:

$5 small blind

$10 my big blind

$35 my opponent opens for a pot-size raise

$25 I call his raise

$75 total pot after I call the raise, and new maximum pot raise

I make it $110 to go ($25 + $75)

In PLO, I can’t simply go all-in and blow my opponents out of the hand like I can in NLH.

![]()

With four hole cards, there are six two-card combinations for a player to combine with the five community cards. As we’ve seen, in Hold’em there are 1,326 possible starting hands. In PLO, there are a staggering 270,725 possible starting hands (52 × 51 × 50 × 49 ÷ 24), about 200 times more than Hold’em.

Although the number of combinations has soared, the method of calculating the combinations is the same as in Hold’em. Let’s try a few examples:

Example 1:

What are the chances of being dealt AAXX in Omaha? 6 ways to choose AA × (50 cards × 49 ÷ 2) = 7,350 7,350 ÷ 270,725 = 2.7%

Example 2:

What are the chances of being dealt a hand with the A♠ and the 5♠ and two other cards?

(50 × 49 ÷ 2) ÷ 270,725 = 0.0045 = 0.45%

Example 3:

How many combinations and probability of being dealt JT98 double-suited?

J9s T8s = 4 × 4 = 16

J8s T9s = 4 × 4 = 16

_________________________________________________________

= 48 combinations / 270,725 = 0.000177 = 0.0177%

Example 4:

How many double-suited hands are there?

48 combinations for each 4 ranks × 13 × 12 × 11 × 10 ÷ 24 = 34,320 combinations

34,320 ÷ 270,725 = 12.67%

Example 5:

What are the chances of being dealt a rainbow hand (four cards with four different suits)?

13 × 13 × 13 × 13 = 28,561 combinations

28,561 ÷ 270,725 = 10.54%

Example 6:

How many hands are exactly single-suited?

270,725 total combinations

− 28,561 rainbow combinations

− 34,320 double − suited combinations

__________

= 207,844

207,844 ÷ 270,725 = 76.77%

![]()

Here is a list of the top 30 starting hands in Omaha:

1. A-A-K-K |

11. K-Q-J-T |

21. Q-Q-A-K |

2. A-A-J-T |

12. K-K-T-T |

22. Q-Q-A-J |

3. A-A-Q-Q |

13. K-K-A-Q |

23. Q-Q-A-T |

4. A-A-J-J |

14. K-K-A-J |

24. Q-Q-K-J |

5. A-A-T-T |

15. K-K-A-T |

25. Q-Q-K-T |

6. A-A-9-9 |

16. K-K-Q-J |

26. Q-Q-J-T |

7. A-A-x-x |

17. K-K-Q-T |

27. Q-Q-J-9 |

8. J-T-9-8 |

18. K-K-J-T |

28. Q-Q-9-9 |

9. K-K-Q-Q |

19. Q-Q-J-J |

29. J-J-T-T |

10. K-K-J-J |

20. Q-Q-T-T |

30. J-J-T-9 |

For all hands, being double-suited (ds) is best, single-suited (ss) is next (and, when applicable, a strong preference for being suited with the Ace), and no suits is a distant third. This list represents about 3.5% of the total number of possible 4-card starting hands in Omaha.

Hands that are double-suited with some connectivity are good hands:

KT98ds

QT86d

These hands are good, but are played mostly for straight potential, with the flush as emergency backup.

Double-paired hands are considered good hands (and even better if suited or double-suited) and are almost always playable:

JJ55, 8877

Ace-suited hands with a medium or high pair and some connectivity are good hands.

Coordinated hands with a few gaps and a suit are mediocre.

J986ds

9754ds*

J865ds

Suited ace hands without much more going for them are considered mediocre, at best.

A♠T♠7♣4♦

Hands with only one low pair (2-7) are generally considered trash hands, unless there is another pair in the hand or the other cards have something seriously good going for them. A♣K♦2♣2♦ isn’t a terrible hand, for instance, but J♣T♣5♦5♠ is considered ugly trash.

Any hand with trips (QQQX, TTTX, etc.) is trash and completely unplayable. Obviously, since trips are bad, quads are even worse. But don’t worry, you’ll only be dealt a hand this bad about 1% of the time.

![]()

The starting hands in PLO are much closer in value than they are in Hold’em. Even the very best hands, like AAKK double-suited, are only marginal favorites over bad hands, like a J♣8♣6♦4♥ rainbow (which has approximately the same value as 85o in Hold’em), at 68% to 32%, or about 2-1. Many players presented with this information automatically assume that since the hand values are so much closer, almost every hand becomes playable. Those players quickly go broke. Hand selection, as in Hold’em, is still extremely important and sets you up for success later in the hand.

The “nuts,” or the best hand possible, is very often the winning hand in PLO. Winning a pot with a hand other than the nuts is the exception, not the rule. With that being the case, it is crucial to play hands that will have many ways to make the nuts.

In Hold’em, I advocate a “raise or fold” strategy. That is still the case in PLO: if I am the first player to voluntarily commit chips to the pot, I raise. I never limp in PLO (or any other poker game, for that matter).* My strategy is still “raise or fold.”

I play hands that have a good chance of flopping the nuts or flopping a premium draw to the nuts—hands like JT98 have an excellent chance of pulling it off. Those hands are very playable, especially if they are suited or double-suited.

Hands with small cards (2, 3, 4, 5) are typically not playable. Many players overvalue hands with small pairs, like K855 and K744. The problem with hands like this is that unless you flop quads, it is nearly impossible to flop the nuts. Even if you flop a set, you have to play the rest of the hand defensively—players will almost always be drawing very live, and occasionally, they’ll have you crushed with a higher set. My advice is to ignore 2, 3, 4, and 5 in your hand unless they are suited with an Ace.

I hate starting hand guides, but here is a good look at requirements for opening the pot in PLO. Notice that playing extremely tight from early position is correct, and that most decent hands become playable from late position.

Pre-flop equities are very, very close in PLO. Even hands that look dombinant aren’t extremely likely to win against even the trashiest looking hands at showdown:

AAXX* vs. JT98 double-suited 56% to 44%

AAKK vs. 4567 double-suited 60% to 40%

No hand is truly dominating against any other hand. In Hold’em, AA vs. 72o has about an 87% chance of winning. In PLO, AAXX vs. 7422 is only about 70% likely to win. Although the pre-flop equities are very close, post-flop playability is extremely vital. In PLO, multi-street betting and hands that go all the way to showdowns are much more common than in Hold’em.

In PLO, there really isn’t much of a chance to steal the blinds—it is a very rare occurrence. If I am the first player to raise the pot, I expect to get at least one caller, and I’m not at all surprised to face multi-way action. Even when I raise from the button, I expect to get called (or raised) from the small or big blind around 50% of the time.

At an average table against normal, tight, aggressive competition, when I open from middle position in a nine-handed game (under the gun in a six-handed game) here is what I expect:

Win the blinds (steal) |

3% |

Heads up, out of position, or three-bet |

28% |

Heads up, in position, or three-bet from the blinds |

20% |

Three-way action |

35% |

Four-way action |

14% |

Three-betting pre-flop in Hold’em will result in many folds and easy pre-flop wins. In PLO, three-betting does not win the pot very often at all. Most players will call a three-bet once they have opened the pot. In PLO, I never three-bet and expect to win the pot pre-flop. When I three-bet in position, I hope to isolate and play with a hand that has good equity and excellent playability. When I three-bet out of position (from the blinds), I’ll always have a first-tier, premium hand.

Some hands in PLO play best when heads up. Hands like AAXX rainbow, KK97 rainbow, AK97 all play better if up against one player. These hands can (and will) win with one or two pair. In multi-way pots, it is rare to see a hand as weak as two pair take down the pot.

Other hands in PLO play best in multi-way pots. Most of these are the “rundown” hands—hands like JT98, T987, and 9876 that play well against many opponents. I either flop a huge draw, the nuts, trips, or I can easily get away from the hand without investing much money. With the lower rundowns (8765, 7654, etc.), the hands become weaker in multi-way action—weak flush draws, straights, and two pair are unlikely to be good if facing significant action.

With the hands that play better heads up, I am always trying to limit the field and play against as few opponents as possible. I will risk a three-bet in an effort to limit the competition. With hands that play better in multi-way pots, I will simply call a pre-flop raise and allow other players to enter the pot behind me more easily. Bottom line: In some hands, usually the high pairs, I want to push people out of the pot. With the straight and rundown hands, I don’t mind pulling opponents into the pot.

|

J♣ T♣ 9♠ 84 |

A♠ A♦ 9♠4 7♥ |

||

Opps |

My Win% |

Opps Win% |

My Win% |

Opps Win% |

1 |

44% |

56% |

63% |

37% |

2 |

31% |

34% |

43% |

28% |

3 |

24% |

25% |

30% |

23% |

4 |

19% |

20% |

22% |

19% |

As you can see from the chart, playing JT98 against two opponents only lowers the win rate by 13% (44% to 31%). Playing AA97 against two opponents lowers the win rate by 20% (63% to 43%).

Position is even more important in PLO than it is in Hold’em. As there are so many multi-street, multi-way pots, being in position is a tremendous advantage. It is much easier to extract value from the “nuts” and save money with second-best hand when in position. It is also easier to bluff successfully.

I strive to play as many pots as possible in position in PLO. If there is a decent chance that I’ll be out of position in a hand, there is a decent chance I’ll just fold all but the best, most playable hands.

AAXX isn’t as powerful as AA is in Hold’em. That should be fairly obvious—in Hold’em, AA is dealt only 1 out of 225 hands, while in PLO, a player is dealt AAXX about 1 out of 40 hands. Many players just lose their minds when they pick up Aces pre-flop in PLO. While AAXX should always open the pot for a raise, it isn’t always worth three-or four-betting.

For three-betting purposes, AAXX hands should be subdivided into good, mediocre, and bad subcategories:

Good AAXX hands are double-suited or have another pair (AA55, AAJJ, etc.) A♣A♦K♦Q♠ is a great hand as well—it is suited with the Ace and has strong connectivity. Good AAXX hands can three-bet from any position and play well against any number of opponents.

Mediocre AAXX hands are usually single-suited with the Ace not having much connectivity: AA96, AAK9, AA52. Mediocre Aces should three-bet in hands where it is likely to be heads up, in position. I rarely three-bet these hands from the blinds—playing out of position is just too difficult.

Bad AAXX hands are usually rainbow hands without connectivity. These hands should rarely three-bet. I will three-bet AAXX from the button against a late position raiser—that is my best shot at getting this hand heads up. These hands are best played for set value.

Many players make the mistake of three-betting bad or mediocre Aces when out of position. The pre-flop raiser will almost never fold, and playing bad or mediocre AAXX out of position is very difficult. You don’t have to play in many of these spots to realize that this is a recipe for disaster. A better play is just to flat-call these hands and then check-fold if the flop isn’t good for your hand. Don’t put another chip in the pot on boards like QJ8 and JT7. AAXX just plays like crap on so many different flops that it isn’t worth a three-bet, despite the fact that you have the best hand at the moment. Remember, opponents aren’t going to fold to a three-bet, and it will be extremely difficult to maintain the lead post-flop.

If you are new to Omaha, odds are you will be excited about seeing AAXX. That excitement will quickly fade after you misplay a few of these “monster” hands and get stacked a few times. Soon, you’ll see bad Aces for what they are: a decent hand that has a hard time flopping the nuts and won’t make much money in most cases when you do. New PLO players might be better off never three-betting mediocre or bad Aces and playing them solely for set-mining purposes.

When playing deep stacked, I am very cautious with this hand. If I open from middle position with mediocre or bad Aces and I get three-bet by a deep-stacked opponent who has position on me, I will not be four-betting very often at all. I’m just going to call the three-bet and check-fold if the flop is scary. When I four-bet pre-flop, my hand might as well be played faceup—a deep-stacked opponent will be able to put tons of pressure on most flops, pressure that a bare pair of Aces will have a hard time standing up against.

For example, playing with $2,500 on the table (250 big blinds deep) at a $5–$10 table, I raise from middle position with A♣A♦7♥2♠—bad Aces—and make it $35 to go. My opponent three-bets to $110 from the button. I four-bet the pot to $330. He calls. $675 in the pot. The flop is J♦6♠5♠. I bet $440, he moves all-in. I hate my hand. Even against my “best case” of A♠J♠T♣9♣, my hand is only 43% to win. Against KQJJ or QJJT, I’m toast and only win 9% of the time.

If I face a three-bet after opening with mediocre or bad Aces and I can’t get about a third of my stack in with a four-bet, I usually just call the three-bet and reevaluate after the flop. If I can get a third or more of my chips into the pot, I’ll go ahead and four-bet and then get it all-in post-flop most of the time.

If I’m fortunate enough to pick up AA, but unfortunate enough to have AAAX or even AAAA, I realize that these hands still have some value. Of course, I’m not likely to flop anything substantial, but these hands have good bluffing potential on almost every “flush” board. Dumping these hands pre-flop isn’t a mistake, but if I’m willing to get creative, I can pull off some spectacular bluffs.

Playing Aces in Omaha is very tough. Playing KK hands is just as difficult. KKXX is almost always a pre-flop opening raise if I’m the first to voluntarily enter the pot. There are some very, very bad Kings that might be a fold UTG in a full nine-handed ring game: Rainbow KK72, KK94 at very active tables probably deserve a tight, early position muck.

If a player opens in front of me, I am only three-betting very good Kings, and then only against a middle- or late-position opening raise. Ideally, I want to play KKXX hands heads up, in position. This is where Kings are the most effective. I am a little more willing to three-bet mediocre KK hands when I have an Ace in my hand—that Ace will decrease the chance that my opponent has AAXX by about 50%, based on straightforward card elimination.

If I open from early position with mediocre or bad KKXX and I get three-bet by a good player in position, I seriously consider dumping my hand. Playing a big pot out of position with a hand that isn’t going to flop well most of the time isn’t my idea of a good time.

For example, if I open K♣K♦9♠5♦ from early position and Phil Galfond three-bets me from the button, my most profitable play is folding (and quickly changing tables).

Bad KKXX hands can call an opening raise for set value if the pot looks like it will go multi-way.

These hands come in a few versions, some with straight potential, others that are mainly played for set value:

Good: QQJT double-suited, QJJT, TT98, TT97, 9987, KsJsJT

Mediocre: QQ98 single suit, KJJsTs, JJ97 double-suited

Bad: QQ84 single suit, JJ83 double-suited, TT72 double-suited

These medium-strength paired hands, even double-suited and with straight potential, aren’t as good as they appear to be. When I flop a flush draw, it won’t be the nut-flush draw and I’ll have to play conservatively. If I flop a set and get action, I can be sure that my opponents will be drawing very live. QQ84 can easily be a significant underdog on a QT7 two-tone board.

Most of the big pots with these medium-paired hands come in set-over-set situations. Realize that the lower your top set is, the more often you’ll be facing a lower set that has good draws against your hand as well:

Example: Q♣J♠T♦T♥

Flop: T♣7♦5♦

If I open this hand for a raise and get a few callers from the blinds, I might be brilliantly ahead in a set-over-set situation. But, the hands with 77 and 55 that will call a pre-flop raise will also have some connectivity that will hit that flop hard for draws, with hands like 7789, 8776, 6554. Although ahead, QJJT isn’t much better than a 2-1 favorite against any of those hands.

These hands do not play well in multi-way pots. I really only want to play these hands in position against a single opponent—that means that they are really only playable from late position when I can open the pot for a raise. Calling a pre-flop raise, even with “good” versions of these hands, can lead to some serious problems post-flop.

Opening bad, uncoordinated queens from any position except the button is too loose. Calling a pre-flop raise with these hands out of position against an early or middle position raise is too loose. Playing these hands in multi-way pots is too loose. Get the idea?

Rundowns, hands like JT98, KQJT, AKQJ, 9876, are all very, very good hands, and in fact, they are my favorite type of hand to play. Not much can go wrong for these hands pre-flop. I will open them from every position and three-bet pretty much indiscriminately. These hands play well when heads up, and they play well in multi-way action too. When I pick up one of these hands, I consider it a green light to get active. Even against AAXX, rundowns hold up well: A rainbow JT98 is about 40% to beat AAXX at showdown.

One of the nice properties of rundowns is that they are relatively easy to play post-flop. If I flop two pair, I’ll have at least a premium straight draw to go with it:

JT98 on a J84 or J93 board, 9876 on a 762 board

All of these flops allow extremely aggressive post-flop play with very little possibility that I’m drawing dead or slim. When I’m in late position and I’m facing an early or middle position raise, I’ll most likely three-bet bad rundowns (T987 rainbow) and try to get heads up in position. With premium rundowns like JT98 double-suited, I’ll most likely call the pre-flop raise and hope to draw some other players into the pot.

Mediocre, unpaired hands can definitely be playable and profitable. Hands like “skip-straights” QT86, J986 certainly have potential, but they are markedly inferior to the “pure” rundown hands. Even hands with only one gap (JT87, 9865) look better than they really are. But if double-suited, these hands become very playable.

Unlike the pure rundowns, these hands play better against limited competition. If I’m in late position and facing an opening raise from middle position, I three-bet with these hands quite liberally and try to isolate in position to give myself the best chance to win the pot with two pair.

If I three-bet and face a four-bet with these hands, I’m definitely going to call if I’m in position. I’m most likely against AAXX-type hands. I can really have my opponent in bad shape on some flops, and my all-in equity against AAXX is 45%. Better yet, after 40% of the flops, I’ll actually be in the lead (though I may not know it).

Bottom line: I play these hands in position and I try to isolate when possible. Post-flop, I get away cheaply when I don’t flop at least top two or a premium draw. Flush draws are viewed as emergency backup, not a feature.

Other playable hands have a suited Ace and some connectivity between the other three cards: A♠9♠8♣7♦, A♣5♣6♦7♥. These hands are particularly playable if I’m the first to open the pot from late position. I never fold A♠9♠8♣7♦ to a single raise. I’ll call a raise with A♣5♣6♦7♥ if I’m on the button, but not from the blinds. Any suited Ace is playable almost without regard to the other cards in a four-way pot on the button. A522 with a suited Ace is (marginally) playable from the blinds, A368 double-suited should probably fold to a pre-flop raise from the small blind, but may be playable three-way and definitely should be played in a four-way pot. Almost all of the playability of these hands comes from the flush draw and flopping trips—every other flop leaves these hands vulnerable and weak.

Hands like 5568 and 2235 are bad hands with huge reverse implied odds. I occasionally play some of these weaker holdings from the button when I can open the pot for a raise, but only if the blinds are weak: passive players and easy to read.

Playing these hands multi-way is a quick and effective way to go broke. You might as well just take out a lighter and set the money on fire. If I just have to play 5568 against a late position opening raise, I’m better off three-betting and then barreling off.

Three-betting, a key strategy in most Hold’em games, is very important in PLO as well. Three-betting in Hold’em often results in winning the pot pre-flop. In PLO, that is not the case. It is extremely rare to see a player fold to a three-bet pre-flop in PLO—they are going to see the flop.

So, consider these two facts:

1) I will almost never get a pre-flop opener to fold pre-flop when I three-bet.

2) Position is more important in PLO than in Hold’em.

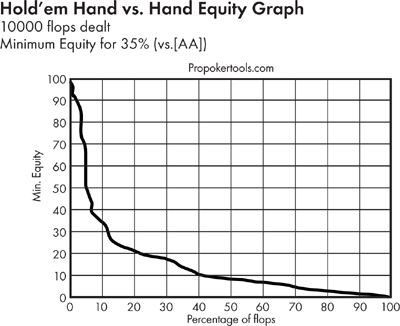

Considering those two facts, it is very clear that three-betting from the small or big blind is a very big no-no. Even with mediocre and bad AAXX, I am very reluctant to three-bet out of position.* Let’s drill down here a bit using the Graph tool at ProPokerTools.

A♣A♥9♠7♦ vs. a cutoff position opening raise with a typical 35% opening range:

Pre-flop all-in equity: 63% for AAXX, 37% for cutoff.

Here is a graph of post-flop equities for the cutoff hand:

On 50% of the flops (Point A), my opponent will have at least 33% equity (probably some sort of flush draw or straight draw), and there is no chance I’m going to get him to fold to a post-flop bet. Worse, on 25% of the flops (Point B), I’ll actually be behind. So, I’m out of position in a three-bet pot, and I’m about to fire a bullet when it is unlikely that I’ll get my opponent to fold, and there’s a decent chance I’m actually behind. Worse yet, when I three-bet out of position, my opponent will be able to put me on a very, very tight range of hands and will be able to peg me with AAXX quite often and accurately.

As an aside, contrast that last graph to the equivalent Hold’em graph, a 35% opening raise and a three-bet with AA:

There are very few flops that significantly improve a 35% opening range against AA in Hold’em.

In PLO, the pre-flop three-bet serves just two purposes:

1. Trap the dead money and isolate the weak post-flop players when in position.

2. Build a pot with a big hand that has an excellent chance to flop the nuts or a big draw to the nuts.

If neither criteria is met, three-betting pre-flop isn’t the best play.

If I open the pot for a raise and get three-bet, most of the time my decision is easy: call and take a flop. Occasionally, I will four-bet. Very rarely, I’ll choose to fold.

In Position

When I’m in position against a three-bettor, I almost never fold. I consider dumping only the very worst, paired hands. If I’ve opened hands like QQ96, JJ54, 9976, and TT85, I might fold to a three-bet. If my hand is unpaired, no matter how bad it is, I’m going to call the three-bet and take a flop in position.

At deep effective stacks of at least 150 big blinds, I four-bet liberally with my premium, rundown hands. I want the ape playing AAXX to go crazy out of position, 300 big blinds deep, when I can have him in such bad shape post-flop.

Getting three-bet and playing out of position can be very problematic. Because of my good hand selection skills, I won’t be out of position often in PLO. Here are some general guidelines for this spot:

![]() Four-betting out of position is not normally a good idea unless I have AAXX and can get at least a third of my stack in pre-flop. The quality of my AAXX hands isn’t as important as the effective stack sizes. If I can get a third of the money in with a four-bet, I do it and then fire a pot-size bet (the rest of my stack) on most flops.

Four-betting out of position is not normally a good idea unless I have AAXX and can get at least a third of my stack in pre-flop. The quality of my AAXX hands isn’t as important as the effective stack sizes. If I can get a third of the money in with a four-bet, I do it and then fire a pot-size bet (the rest of my stack) on most flops.

![]() The worst of the paired hands can be folded without much regret. If I open a bad KK hand from early position in a nine-handed game (KK96) and get three-bet from the button, I can comfortably fold. Same with a QQT7-type hand from the cutoff. Paired hands have very little playability post-flop out of position.

The worst of the paired hands can be folded without much regret. If I open a bad KK hand from early position in a nine-handed game (KK96) and get three-bet from the button, I can comfortably fold. Same with a QQT7-type hand from the cutoff. Paired hands have very little playability post-flop out of position.

![]() Unpaired hands that were good enough to open should be good enough to call all three-bets. That is actually a pretty good indicator when considering opening from early position—if I won’t be happy to call a three-bet and play out of position, I should dump the hand and refuse to open the pot.

Unpaired hands that were good enough to open should be good enough to call all three-bets. That is actually a pretty good indicator when considering opening from early position—if I won’t be happy to call a three-bet and play out of position, I should dump the hand and refuse to open the pot.

![]() Excellent AAXX hands, like AAJ9ds, can four-bet, even out of position.

Excellent AAXX hands, like AAJ9ds, can four-bet, even out of position.

If I have a premium rundown and there is a bet and raise in front of me, I don’t get scared off my hand—these are still excellent hands. Other hands that are playable in this spot are two pair hands like 9988, 8866. Hands like QQJJ are worse than they look—your opponents will very often have “blockers” to hands like this (AKQJ, KQJT, QJT9). As a result, those hands are less likely to flop a set. Even if I do flop a set, my opponents will often have big straight draws and not be all that far behind.

When I’m in late position and there are several limpers, I will “squeeze” with a big pot-size bet on a wide range of hands. This is one spot where I expect my opponents to fold and I might be able to isolate some fishy money and play a pot in position. I’ll almost never make this play from the blinds, however. I don’t want to play a big multi-way pot out of position, even with AAXX. Out of position in what will be a 4- or 5-way pot, I’ll just play my bad AA hands for set value. Players making the transition to PLO from Hold’em are really surprised that the pre-flop squeeze, one of the bread-and-butter plays in Hold’em, just doesn’t work in PLO.

While squeezes (especially out of position) aren’t very effective, reverse squeezes can be an extremely good play. Again, a reverse squeeze operates when you flat-call an early position opening raise, get three-bet from behind, and then put in a big four-bet after “trapping” the pre-flop opener and three-bettor. Mostly, I’ll make this play when I have bad AAXX-type hands that weren’t good enough to three-bet pre-flop, but am more than happy to four-bet and get a significant amount of my stack in.

An early position player opens for a pot-size raise to $35 in a $5–$10 game. With 150 big blinds in my stack, I don’t feel comfortable three-betting with A♣A♦9♠5♥. I call. The button, a frequent and aggressive three-bettor, raises the pot to $140. The opener calls. Now, I can four-bet to $575 with what is almost assuredly the best hand and get in a little more of a third of my stack pre-flop.

In PLO, limping into the pot pre-flop might be a viable play. Early in the tournament, there are plenty of fish taking a shot at the game without much experience. Raising pre-flop chases away all the fishy money. I don’t really want the Q♣7♦5♠4♣ to fold when I have A♣Q♦J♣8♥. I want that fish to get in the pot, flop a flush or flush draw and go broke. If I raise, the fish will almost certainly fold such a bad hand.

Late in most PLO tournaments, the stack sizes will degenerate to around 20–40 big blinds. Here, too, I might consider pre-flop limping from early and middle position. With short effective stacks, there simply isn’t enough maneuverability when I raise pre-flop.

I play extremely, ultra-tight from the blinds in PLO tournaments. I simply don’t want to play pots out of position when there is no possibility of a re-buy. If I’m short-stacked in a PLO tournament, I don’t rush to three-bet or four-bet pre-flop out of position. As a short stack, I am never going to get my opponent to fold pre-flop. The “stop and go” from the blinds is a better short-stacked play: call the pre-flop raise, and then fire “pot” after the flop. That play is much more difficult to combat and gives me a chance to win the pot without going to showdown. With the stop and go, I also have the luxury of deciding to give up on the worst of flops and preserve the small amount of tournament equity I have left.

Example: I have JT98 and I have 11 big blinds left in the big blind. Middle-position player opens the pot, and I consider a three-bet all-in. But that play will never win the pot right away—my opponent will call my three-bet 100% of the time. A better play is to just call the raise and then fire at the pot.

![]()

In PLO, almost every hand is contested and goes to the flop. Playing well post-flop is required to be a winning PLO player. A player with fire-hose-sized leaks in the pre-flop game can still win if he possesses great post-flop skill, but the opposite is certainly not true.

The key to good post-flop play is to visualize the turn. To put in much action on the flop, I really want to either already have the nuts or have at least 8 cards that can come on the turn that will give me the nuts. When I don’t have the nuts and there aren’t many cards on the turn that can make me the nuts, I play cautiously (unless I’m bluffing).

It is important to also visualize the turn with respect to the opponent’s range of hands. There are many instances where I can currently be in the lead with the best hand, but will likely be behind if the hand goes all the way to showdown.

There are many times in PLO where you will flop the stone-cold nuts and actually not be a favorite to win the hand at showdown. These situations are much more frequent than you might expect, but taking a look at them will give you a good idea about the challenges and subtlety you will face in post-flop play.

Hand: Q♣J♦9♠8♠

A middle-position player opens for a post-size raise and I call from the button. The flop comes perfect for my hand and gives me the nuts:

Flop: A♠K♥T♥

The action on the flop is fast and furious—raise, re-raise, raise, re-raise, all-in. I couldn’t be more thrilled, until my opponent turns over A♠A♥J♥7♠. They have top set, a gut-shot straight (to tie), a flush draw, and a backdoor-flush draw. An equity analysis shows that the “nuts” just cost me a ton of equity:

Q♣J♦9♠8♠ = 31.71% equity

A♠A♥J♥7♠ = 68.29% equity

On the same flop with that action, it isn’t inconceivable that my opponent is free-rolling against me with a hand like A♥K♦Q♥J♦. We both have a straight, but he has 9 outs to a flush.

Q♣J♦9♠8♠ = 22.99% equity

A♥K♦Q♥J♠ = 77.01% equity

In multi-way pots, it isn’t unheard of to flop the nuts and be forced to fold before putting a single chip in the pot. For example:

A middle-position player opens the pot, cutoff calls, and I call from the big blind with a decent rundown hand 9♠8♠7♦5♥.

Flop: J♦T♦7♥

I check (intending to check-raise), opener bets the pot, cutoff raises the pot, and the action is on me.

Despite the fact that I currently have the nuts, this is a clear fold. If my opponents are rational, I’ll be up against a minimum of a wrap (AKQX) and a flush draw, and it could be even worse:

Flop: J♦T♦7♥

A♣Q♠J♠J♣ 38% equity

K♦Q♦J♥9♣ 50% equity

9♠8♠7♦5♥ 12% equity ← My hand is nearly dead

Take a long, careful look at this hand. After flopping the nuts, the hand has only 12% equity. There aren’t many players who can flop the nuts and fold; luckily, it doesn’t come up often.

Yes, this example is extreme and contrived, but it should scare the living hell out of you and wake you up to the possibilities of getting your money in very poorly post-flop. Many of these problems can be mitigated with a “backup” plan—a draw, even a gut-shot or backdoor flush draw, can significantly improve a hand’s overall equity. For instance, here, I flop the nuts but my “backup plan” is a King to make a higher straight, and runner-runner to make the Ace-high flush.

Flop: J♦T♦7♥

A♣Q♠J♠J♣ 37% equity

K♦Q♦J♥9♣ 40% equity

9♠8♥A♥Q♣ 23% equity

On coordinated boards, the current nuts won’t be the nuts very often on the river, especially in multi-way pots. Don’t get carried away and play too conservatively. With 9♠ 8♠ 7♦ 5♥ on a 6-4-3 two-tone flop, just get as much money in as you can—your opponents are very unlikely to have a set and a flush draw on a board like that.

As we’ve seen, it is quite common to be “behind” after the flop, but have more than 50% equity if the hand goes to showdown. Most commonly, these are hands with huge straight draws. These multi-card straight draws are called “wraps” and can be played extremely aggressively post-flop:

K♠Q♦9♥8♣

Flop: J♣T♦4♥

Here, any A, K, Q, 9, 8, or 7 will make a straight. Better yet, only the K and Q make a straight that isn’t the nuts. There are 20 cards in the deck that will make a great hand, and 14 make the nuts. Clearly, this is a flop combination that can be played very aggressively. Even against a set, with a wrap, you’re still in good shape:

Flop: J♣T♦4♥

K♠Q♦9♥8♣ 51%

JJXX 49%

Beware of straight draws that look better than they are—you should significantly discount the value of straight draws that aren’t the nuts. When you have a hand like this and your opponent has the full wrap, you may be in bad shape:

My hand: K♣Q♣T♣9♠ 38%

Opponent: A♠K♠T♦9♦ 72%

Flop: Q♠J♠4♦

Here, I flop top pair and a wrap. And yet, against a flush draw and wrap, I’m a big underdog. The lesson here is clear: When the flop is two-toned, a wrap should be played much more cautiously.

If I’m in the betting lead after the flop, the natural tendency is to make a continuation-bet (C-bet). In PLO, the correct use of the continuation-bet is much more difficult than it is in Hold’em. There isn’t some master chart of all situations, obviously, so here is a partial list of some things I think about before firing that post-flop continuation-bet:

![]() If I don’t think I have the best hand and I don’t have quite a few outs to the nuts, I rarely C-bet. Draws to second nuts and top two pair (where the second pair won’t make a straight) can warrant a continuation-bet as well.

If I don’t think I have the best hand and I don’t have quite a few outs to the nuts, I rarely C-bet. Draws to second nuts and top two pair (where the second pair won’t make a straight) can warrant a continuation-bet as well.

![]() If the board is extremely dry (8-5-2 rainbow) and I whiffed (say with KQJT), I might make a C-bet as a bluff; my opponents are unlikely to have good hands.

If the board is extremely dry (8-5-2 rainbow) and I whiffed (say with KQJT), I might make a C-bet as a bluff; my opponents are unlikely to have good hands.

![]() The best dry flops to C-bet are King-high flops—K-8-4 or K-7-2–type boards. I will get credit for a King (maybe even pocket Kings) and I normally won’t face much resistance.

The best dry flops to C-bet are King-high flops—K-8-4 or K-7-2–type boards. I will get credit for a King (maybe even pocket Kings) and I normally won’t face much resistance.

![]() If I have “blockers” to the nuts, I am more willing to fire a C-bet. For instance, if I have TTXX on a J-9-4 board, I fire away—the chances that my opponent will have a huge wrap are pretty small, and there will be tons of turn cards that will give me an excellent, profitable bluffing opportunity. My opponent doesn’t know that I’m betting with blockers—I could just as easily be betting with a huge wrap.

If I have “blockers” to the nuts, I am more willing to fire a C-bet. For instance, if I have TTXX on a J-9-4 board, I fire away—the chances that my opponent will have a huge wrap are pretty small, and there will be tons of turn cards that will give me an excellent, profitable bluffing opportunity. My opponent doesn’t know that I’m betting with blockers—I could just as easily be betting with a huge wrap.

![]() On monotone boards, I almost always make a C-bet. If my opponent doesn’t have a flush, they will have a hard time continuing on with the hand.

On monotone boards, I almost always make a C-bet. If my opponent doesn’t have a flush, they will have a hard time continuing on with the hand.

![]() If the board has two cards of the same suit (two-toned) and I have the “naked Ace” of that suit, I frequently C-bet. If the board flushes on the turn or river, I will be able to bluff effectively.

If the board has two cards of the same suit (two-toned) and I have the “naked Ace” of that suit, I frequently C-bet. If the board flushes on the turn or river, I will be able to bluff effectively.

![]() If there are many bad turn cards for my hand, I don’t feel like I have to C-bet to “protect” my hand. Flopping top two pair on a J-T-6 board is good, but as we’ve seen I am a significant underdog to wraps. I can just check (and call) and reevaluate after the turn. There is no really good reason to blow the pot up out of position when my hand is so vulnerable. I’m more concerned with protecting my stack than my hand.

If there are many bad turn cards for my hand, I don’t feel like I have to C-bet to “protect” my hand. Flopping top two pair on a J-T-6 board is good, but as we’ve seen I am a significant underdog to wraps. I can just check (and call) and reevaluate after the turn. There is no really good reason to blow the pot up out of position when my hand is so vulnerable. I’m more concerned with protecting my stack than my hand.

![]() C-bets can help me realize my current equity with hands that can pick up monster draws on the turn, but don’t really have the right odds to check and call a pot-size bet. Essentially, with these hands I C-bet as a semi-bluff—I might get my opponent to fold, and if not, I might pick up a good draw on the turn.

C-bets can help me realize my current equity with hands that can pick up monster draws on the turn, but don’t really have the right odds to check and call a pot-size bet. Essentially, with these hands I C-bet as a semi-bluff—I might get my opponent to fold, and if not, I might pick up a good draw on the turn.

Flop: 9♣4♠2♦

Here, I have absolutely nothing, but if I’m out of position with the betting lead, I C-bet anyway. If I get raised, I can dump it without worry, and if my opponent calls, I can pick up a nut-flush draw or a wrap or even a wrap and a flush draw on the turn quite easily. This hand has substantial equity, but I can’t just check and call out of position hoping to pick up a draw on the turn.

![]() I C-bet when the flop is very unlikely to have hit my opponent’s range. Say a player opens from late position and I three-bet on the button and get called. The flop comes 5-6-7 rainbow. This is a great flop to C-bet. My opponent will have a really hard time calling with over-pairs and big rundown-type hands—exactly the hands that make up a substantial part of his range.

I C-bet when the flop is very unlikely to have hit my opponent’s range. Say a player opens from late position and I three-bet on the button and get called. The flop comes 5-6-7 rainbow. This is a great flop to C-bet. My opponent will have a really hard time calling with over-pairs and big rundown-type hands—exactly the hands that make up a substantial part of his range.

![]() I consider making smaller than normal C-bets in three-bet pots. Bets as small as a third of the pot can be very effective. I can get away with cheap bluffs, or I can induce some monkey-action from opponents when I have the goods. My small bet will charge them for some bad draws like gut-shots and weak flush draws. I want to bet most flops, but I want to be able to bluff as well. Most players aren’t capable of raising a C-bet without the nuts because they’ll be afraid of getting it in really bad.

I consider making smaller than normal C-bets in three-bet pots. Bets as small as a third of the pot can be very effective. I can get away with cheap bluffs, or I can induce some monkey-action from opponents when I have the goods. My small bet will charge them for some bad draws like gut-shots and weak flush draws. I want to bet most flops, but I want to be able to bluff as well. Most players aren’t capable of raising a C-bet without the nuts because they’ll be afraid of getting it in really bad.

![]() If I make a small C-bet and get called, my opponent will have a very wide range. Wide ranges don’t play all that well on most turns and rivers. On the turn, I’ll have a good shot at taking the pot away against a range not worthy of raising a flop C-bet.

If I make a small C-bet and get called, my opponent will have a very wide range. Wide ranges don’t play all that well on most turns and rivers. On the turn, I’ll have a good shot at taking the pot away against a range not worthy of raising a flop C-bet.

![]() If my C-bet gets raised, I need a big hand to continue on, especially if I’m out of position. Even folding J♥T♥8♦6♠ on a J♣8♣5♥ board isn’t completely ridiculous or too tight against a good, tight player.

If my C-bet gets raised, I need a big hand to continue on, especially if I’m out of position. Even folding J♥T♥8♦6♠ on a J♣8♣5♥ board isn’t completely ridiculous or too tight against a good, tight player.

If I have the betting lead and position and my opponent checks to me, it seems nearly automatic to make a C-bet. In PLO, though, checking back and seeing the turn has much more going for it than many players realize.

![]() I check-back when my hand is weak, but there are lots of good turn cards that could give me a hand that can continue aggressively.

I check-back when my hand is weak, but there are lots of good turn cards that could give me a hand that can continue aggressively.

![]() I check-back with weak draws when I can’t or don’t want to call a check-raise. If I flop a Queen-high flush draw with a gut-shot, for instance, this is a good time to check-back. I wouldn’t call a check-raise with that hand, but it has some equity that can be realized by checking and seeing the turn.

I check-back with weak draws when I can’t or don’t want to call a check-raise. If I flop a Queen-high flush draw with a gut-shot, for instance, this is a good time to check-back. I wouldn’t call a check-raise with that hand, but it has some equity that can be realized by checking and seeing the turn.

![]() I check-back with top and bottom pair hands that have good showdown value but can’t stand a raise. I might get more value from these hands by inducing turn and river bluffs than I’ll get by betting.

I check-back with top and bottom pair hands that have good showdown value but can’t stand a raise. I might get more value from these hands by inducing turn and river bluffs than I’ll get by betting.

![]() In multi-way pots, I check-back even more often—I am much more likely to face a check-raise when there are multiple players in the pot.

In multi-way pots, I check-back even more often—I am much more likely to face a check-raise when there are multiple players in the pot.

Trapping (or slow-playing) is not very common in PLO given all the draw possibilities. But, occasionally, I’ll have a hand like QQ76 and flop Q-5-4 rainbow, and trapping seems to be the best course of action. But, even with that flop, I’m not thrilled to see an A, 2, 6, or 7 on the turn—those cards might well make my opponent a straight. And I almost never slow-play on two-tone boards.

After trapping on the flop, I just barrel off and bet the pot on all turn cards and hope that my opponent picked up enough of a draw or hand to make a bad bet or call. I could even get lucky and get my opponent to do some crazy stuff on the turn when I slow-play a hand like this—perhaps they pick up second set, or a big wrap. Either way, with only one card to come, they’ll be drawing to only about a 30% chance to win.

For a trap or slow-play to be prudent, everything needs to be locked up and the flop texture has to miss the opponent’s range. “Trapping” with the nuts on two-tone locked-down boards can also be effective. With 9875 on a J♣T♠7♠ board, I might just check the flop and hope for a “safe” turn card. The danger in betting this hand is getting check-raised by straight-flush-wrap draws—I may have the nuts now, but my hand often won’t be very good after the turn and river.

Check-raising on the flop in PLO is a great play, and often is the most effective weapon:

![]() I consider check-raising for a bluff on locked-down boards, like 7-5-4 rainbow. Unless my opponent flopped the nuts, I will win the pot most of the time. If I get called after check-raising, I reevaluate after the turn—against novice opponents who always three-bet with the nuts, I can make a small turn bet (a third of the pot) and then barrel off the river if the board doesn’t pair—opponents are almost always on a set in these spots.

I consider check-raising for a bluff on locked-down boards, like 7-5-4 rainbow. Unless my opponent flopped the nuts, I will win the pot most of the time. If I get called after check-raising, I reevaluate after the turn—against novice opponents who always three-bet with the nuts, I can make a small turn bet (a third of the pot) and then barrel off the river if the board doesn’t pair—opponents are almost always on a set in these spots.

![]() If I’m going to check-raise-bluff on locked-down boards, then I should also check-raise with the nuts for balance. My opponents will start making very tight check-backs in position because they are afraid of my check-raise.

If I’m going to check-raise-bluff on locked-down boards, then I should also check-raise with the nuts for balance. My opponents will start making very tight check-backs in position because they are afraid of my check-raise.

![]() I check-raise and barrel off on monotone boards when I hit the naked Ace. If I play this hand aggressively enough, it will be nearly impossible for my opponents to keep making crying calls as the pot gets bigger and bigger.

I check-raise and barrel off on monotone boards when I hit the naked Ace. If I play this hand aggressively enough, it will be nearly impossible for my opponents to keep making crying calls as the pot gets bigger and bigger.

![]() I consider check-raising with blockers to the nuts. If I have JJ77 and the flop is 9-6-5 rainbow, this is a good time to go for a check-raise bluff. With two sevens in my hand, my opponents are unlikely to have a straight.

I consider check-raising with blockers to the nuts. If I have JJ77 and the flop is 9-6-5 rainbow, this is a good time to go for a check-raise bluff. With two sevens in my hand, my opponents are unlikely to have a straight.

![]() I am unlikely to pull off a check-raise bluff when the board is two-toned. I won’t get my opponent to fold the nut-flush draw.

I am unlikely to pull off a check-raise bluff when the board is two-toned. I won’t get my opponent to fold the nut-flush draw.

When I’m considering a check-raise on the flop, I usually have either the nuts or air. I’m also willing to check-raise with dominating draws when I have a pair with a good redraw.

Floating in PLO is just not very common. If my opponent bets the flop and I don’t really have anything, it is usually not wise to continue. Very infrequently, I consider calling that flop bet and trying to hit a great turn card. For example, with KQJ9 double-suited on a T-6-4 board, I could consider calling a flop bet to try to pick up a wrap or a flush draw on the turn. Of course, I’ll play AT98 exactly the same way on the flop, so I won’t be giving much away. Now, if a Queen hits the turn, I’ll be in excellent shape to call or raise a turn bet.

Essentially, I float the flop to pick up a draw to the nuts on the turn. Do not overuse this play—use it only for very specific, targeted situations.

Donk betting (betting into the pre-flop raiser before your opponents have been given a chance to act on their hand) is much more common in PLO than in Hold’em. With so many potential draws, donking with a strong but vulnerable hand has a lot going for it.

![]() Donk betting is fine if I think my opponent is likely to check-back with a hand that could pick up significant equity on the turn.

Donk betting is fine if I think my opponent is likely to check-back with a hand that could pick up significant equity on the turn.

![]() I don’t donk into locked-down boards—I go for the check-raise instead. This matters a great deal. Firing a pot-size bet on a 9-6-5 rainbow board isn’t nearly as effective as check-raising. If I donk, my opponent will wonder why I didn’t check-raise, and they are much more likely to play back.

I don’t donk into locked-down boards—I go for the check-raise instead. This matters a great deal. Firing a pot-size bet on a 9-6-5 rainbow board isn’t nearly as effective as check-raising. If I donk, my opponent will wonder why I didn’t check-raise, and they are much more likely to play back.

![]() I donk with hands that aren’t strong enough to call a post-flop pot-size bet and can’t check-raise. Essentially, I’m trying to either take down the pot or give myself some equity when I get called.

I donk with hands that aren’t strong enough to call a post-flop pot-size bet and can’t check-raise. Essentially, I’m trying to either take down the pot or give myself some equity when I get called.

![]() I donk bet in multi-way pots when it is very unlikely that I’ll see multi-way action on the turn. For example, a player raises from middle position, the button calls, and I call from the big blind. The flop comes T-4-2 rainbow. This is a good spot to donk with JJXX or KKXX. I don’t expect to get two callers on a dry flop like that. Of course, I’ll fold if I get raised, but I’ll pick up the pot often enough to justify the investment. I will not be well balanced in this spot, but this play is difficult to exploit.

I donk bet in multi-way pots when it is very unlikely that I’ll see multi-way action on the turn. For example, a player raises from middle position, the button calls, and I call from the big blind. The flop comes T-4-2 rainbow. This is a good spot to donk with JJXX or KKXX. I don’t expect to get two callers on a dry flop like that. Of course, I’ll fold if I get raised, but I’ll pick up the pot often enough to justify the investment. I will not be well balanced in this spot, but this play is difficult to exploit.

The “naked Ace” is the Ace of the suit that has flush potential with the board. When I have that card in my hand, my opponent can never be drawing to the nut flush. I can play all of my draws more aggressively, and I can effectively barrel the turn and river if a flush card comes. It will be very difficult for my opponent to call a pot-size bet on the turn or river with the third or fourth nuts. I will get called, of course, but getting caught bluffing with the naked Ace will make the times that I’m barreling off with the made flush that much more profitable. And, because I practice good hand selection, I’ll have a suited Ace many, many more times than I’ll have the naked Ace—probably two to three times more often. Many players aren’t willing to fire that third big bullet on the river—they’ll bluff with the naked Ace on the flop, fire a second bullet on the turn, and then chicken out at the river. That river bet was the most important of the three, though—if you’re not willing to fire three bullets speculatively, then don’t fire the first two either. Note that stack sizes are very relevant here. If I’m not going to have a 3/4-size pot bet on the river, then this play will be much less effective.

I won’t be flopping small sets very often—there aren’t many hands with small pairs in my pre-flop raising or calling range. If I happen to have a small pair and flop a small set, they are extremely difficult to play. The biggest danger, of course, is running into set over set—when that happens, I’ll be drawing to one out (quads) and be in some really big trouble. With small sets, the best course of action is usually to try to play small-ball on the flop and reevaluate on the turn. Set-over-set situations constitute almost the entire profit margin of many winning players. If for some reason I find myself playing 7789 against an early position raiser and the flop comes A-K-7, I realize that there are many more playable combinations of AAXX and KKXX than there are of AKXX for my opponent. If I face opposition on a flop like this, my opponent is very likely to have the nuts—this is a flop where I can definitely lay down the bottom set and feel pretty good about my decision.

I keep my options open for the turn and see how things develop. I’m not in a big rush to get my chips in the middle with small or second sets. There are many turn cards that can come that might give me a better chance to win the pot by turning my “made hand” into a bluff or semi-bluff. When I rush to get my money in on the flop, I can find myself in a set-over-set situation or up against a wrap—in either case, I don’t like my hand very much.

Deep-stack PLO games are rare online, but it’s easy to find live games where the average stack is 1,000 big blinds deep. With stacks this big, PLO becomes a very psychological game of cat and mouse and can be very profitable with some adjustments:

![]() All the real money is made on the turn and the river in deep-stack PLO games. You need to be willing to put in big bets when your opponent has a weak range and you’re at the bottom of your range.

All the real money is made on the turn and the river in deep-stack PLO games. You need to be willing to put in big bets when your opponent has a weak range and you’re at the bottom of your range.

![]() Leverage position and be willing to three-bet on the button quite liberally. Hands that were easy folds to an opening raise when playing with 100 big blinds become near mandatory three-bets when players are 1,000 bigs deep.

Leverage position and be willing to three-bet on the button quite liberally. Hands that were easy folds to an opening raise when playing with 100 big blinds become near mandatory three-bets when players are 1,000 bigs deep.

![]() In a 6-max PLO deep-stack game, you can easily play a 50/40/15 pre-flop game without much difficulty if you’re a good post-flop player. That means you’re voluntarily putting chips into the pot pre-flop 50% of the hands, you’re raising with 40% of your hands, and three-betting with 15% of your hands. Get in there and mix it up in position.

In a 6-max PLO deep-stack game, you can easily play a 50/40/15 pre-flop game without much difficulty if you’re a good post-flop player. That means you’re voluntarily putting chips into the pot pre-flop 50% of the hands, you’re raising with 40% of your hands, and three-betting with 15% of your hands. Get in there and mix it up in position.

![]() Winning players are willing to risk bluffing on the river with a big pot-size bet. That takes balls. The difference between strong hands and weak is hugely magnified in deep-stack games.

Winning players are willing to risk bluffing on the river with a big pot-size bet. That takes balls. The difference between strong hands and weak is hugely magnified in deep-stack games.

Locked-down boards are hands where it is possible to flop the nuts and there are no flush draws present. Flops like 9-6-5, 6-7-8, 4-6-8 are all locked-down boards.* I am willing to make some fancy plays on boards like this—mostly check-raises, especially if I’ve called a pre-flop raise from the blinds. My opponents will have a very, very hard time continuing in the hand unless they flopped the nuts as well.

Another good, dry board to try this play on is an Ace-high board like A-7-4. Say I open from middle position and get three-bet from the button. I call. On a board like this, I can check-raise quite comfortably, even if I don’t have much of a hand. My opponent will either have a rundown hand like JT98, KQJT, etc., or they’ll have AAXX. In short, they’ll either have the nuts or a hand that won’t be able to stand a check-raise. Some combinatorics show that there are simply many more combinations of rundown hands than there are AAXX. A check-raise in this spot should show a nice profit. Again, it is important to note that I don’t make this play against players who will only three-bet pre-flop with AAXX hands—that would be suicide. Even if they suspect that I’m making a play, not many players are willing to put me (and their stack) to the test. (Note: Dry King-high flops are not at all good to get creative with—there are simply too many combinations that won’t fold.)

If I get check-raised on a locked down board having flopped top set, my instinct is to get it all-in as soon as possible. However, this is usually a mistake unless I have an effective stack size of less than about 60 big blinds. Calling is a much better play. Most of the time, my opponent will be polarized with the nuts or air. If I shove against this polarized range, I automatically lose—they fold every hand I can beat and get it in with the nuts. I’m certainly not going to fold top set, so calling must be right if the stacks are deep. I’ll give them an opportunity to barrel the turn with their bluffs, keep the pot small when they are probably drawing very slim, and keep my options open for the turn.

![]()

The turn is the most important street in Omaha—the bets are bigger and the consequences of being wrong are more severe. As the name suggests, the entire complexion of a hand can and often does change on the turn. With only one card to come, the turn is where I really put some pressure on opponents drawing to a flush or straight.

There are two key fundamentals to keep in mind with respect to turn play:

![]() If a player has 13 outs, the hands are in equilibrium.

If a player has 13 outs, the hands are in equilibrium.

![]() It is vital to keep your range uncapped.

It is vital to keep your range uncapped.

Everything else in turn play revolves around those two principles. Let’s see how it all works together.

On draw-heavy boards, the player with the worst hand typically has 12 or 13 outs. For example, a flush draw with a gut-shot straight draw versus the current nuts:

|

Flop |

Flop Equity |

Turn |

Turn Equity |

Me: J♣ T♣ 9♣ 7♣ |

Q♠ T♠ 8♣ |

58% |

2♦ |

70% |

Opp: A♠ J♠ 5♥ 5♦ |

|

42% |

|

30% (12 outs) |

With 30% equity, it isn’t a mistake for a player to call a pot-size bet getting 2 to 1 on his money:

There’s $100 in the pot. I bet $100 on the turn. My opponent has to call $100 to win a pot of $300 ($100 ÷ 300 = 33%). Calling this bet is only slightly unprofitable, but the implied odds of hitting should be adequate compensation.

Note that even check-raising the pot doesn’t gain all that much against a player with 13 outs:

There’s $100 in the pot, I check, my opponent makes a semi-bluff of $100, and I check-raise the pot to $400. They have to call $300 to win a pot of $600. Again, my opponent is getting the same 2 to 1 on their money and has an automatic call with 13 outs.

A check-raise did get them to put in $400 to win the initial $100 in the pot, so they did make a small equity error with that first $100 bet of about $44 or so.

Mashing “pot” bets against a guy with 13 outs doesn’t really accomplish anything. In fact, it just balloons the pot and will make the river decisions much tougher. Betting does get some helpful information that will lead to some good lay-downs on the river, but the same information can often be gleaned with smaller bets.

Keeping my range uncapped on the turn is one of the most important betting strategies in PLO. If my actions and story cap my range, I become really easy to bluff. When I have the betting lead in the hand, the best way to accomplish this is by betting small (one third to one half of the pot) with my entire range on most boards. This small bet keeps my range uncapped—I could still have air, nuts, or anything in between.

Small bets have a lot going for them:

![]() When I have the nuts, I will get called by worse.

When I have the nuts, I will get called by worse.

![]() When I have air, I occasionally elicit some folds.

When I have air, I occasionally elicit some folds.

![]() When I have a mediocre hand, I can get a little value when I’m good and save money when I’m behind.

When I have a mediocre hand, I can get a little value when I’m good and save money when I’m behind.

![]() I get some valuable information at a cheap price, and can set up some good river bluffs and value bets.

I get some valuable information at a cheap price, and can set up some good river bluffs and value bets.

I’m unlikely to induce an opponent with 13 or more outs to make a serious mistake. I give my opponents plenty of rope to hang themselves with when I make these small, balanced turn bets. This is a very difficult style to combat.

Here is an example of keeping range uncapped on the turn:

I raise the pot pre-flop from the cutoff with Q♠J♦9♦7♣ and the button calls. Flop comes T♠7♠5♦. I make a continuation-bet of 3/4 pot. My opponent calls. Turn: Q♣.

Here, I have top and middle pairs and a straight draw, but I’m worried about the flush. Many players check and fold or check and make a crying call. If I check-call, I cap my range and make myself really easy to bluff on the river. Instead, I lead a third of the pot, and here are all the good things that can happen:

![]() I might get a worse hand to call hoping to river a full house (Q965, 7654).

I might get a worse hand to call hoping to river a full house (Q965, 7654).

![]() I might get a better hand to fold (AKQT, no flush).

I might get a better hand to fold (AKQT, no flush).

![]() I give myself a decent price to pick up a full house on the river if I’m up against a weak flush and my opponent doesn’t raise.

I give myself a decent price to pick up a full house on the river if I’m up against a weak flush and my opponent doesn’t raise.

![]() If my opponent calls, I can be pretty sure that he doesn’t have the Ace-high flush. I can then make a pretty big bluff on the river and get him to fold the Q- and J-high flushes quite often—my opponent’s call on the turn caps his range—exactly what I avoided doing when I made a small bet at the turn.

If my opponent calls, I can be pretty sure that he doesn’t have the Ace-high flush. I can then make a pretty big bluff on the river and get him to fold the Q- and J-high flushes quite often—my opponent’s call on the turn caps his range—exactly what I avoided doing when I made a small bet at the turn.

Maintaining balance in this spot is imperative. I bet small when I have it, and bet small when I don’t. In the same spot, I’d make a one-third-pot bet with the nut flush as well.

This is a very difficult style to combat. Opponents might just put in a big raise with a non-nut flush, thinking that I have a set—when I have the nut flush in that spot, cha-ching!

It is important to understand that even on the turn you can have the nuts, and still be “behind” in expectation. These situations are rare, but when they come up, they can be punishing.

|

Flop |

Flop Equity |

Turn |

Turn Equity |

Me: Q♥ Q♣ 9♥ 7♣ |

Q♠ T♠ 8♣ |

39% |

5♦ |

35% |

Opp: A♠ J♠ 9♦ 8♦ |

|

61% |

|

65% (26 outs) |

Many players would be more than happy to get in 500 big blinds in this spot—when you do, you can be absolutely certain that you’re up against exactly this type of hand and you’ll have to get very lucky to fade the river.

Ace-high boards are good to double-barrel on. On a flop like a rainbow A-J-7, opponents call a continuation-bet with lots of drawing hands (KQT9, QT98, JT98, AT97) and weak two-pair hands (JT97, J987, KJ97). A pot-size bet can set up the turn for another big bet that will really put the pressure on.

From my opponent’s perspective, a hand like AT97 on a board of AJ73 could be drawing to as few as four outs, and probably doesn’t have more than six. If my opponent calls my flop bet and the turn bricks off, firing another barrel can be extremely effective. This kind of play is so effective that I can do this without any equity in the hand—it might not be entirely smart, but I can get away with it occasionally.

There are many profitable spots for bluffing on the turn:

![]() On paired boards with a flush draw (7-7c-5c, 9-9c-5c, Jc-6c-6, etc.), firing a second barrel on any card that doesn’t complete the flush has a good chance of success. Opponents will have a fairly wide range on this flop and will peel one off with flush draws. But, now that the pot is bigger, it will be more difficult for them to continue. An Ace on the turn is the best card to barrel on—an opponent might have called a flop bet with QXX on a Q77 board and will likely now fold to a turn bet.

On paired boards with a flush draw (7-7c-5c, 9-9c-5c, Jc-6c-6, etc.), firing a second barrel on any card that doesn’t complete the flush has a good chance of success. Opponents will have a fairly wide range on this flop and will peel one off with flush draws. But, now that the pot is bigger, it will be more difficult for them to continue. An Ace on the turn is the best card to barrel on—an opponent might have called a flop bet with QXX on a Q77 board and will likely now fold to a turn bet.

![]() When I have a pair, a flush draw, and over-cards that won’t make a straight for my opponent, this is a good spot for a second bullet. My hand is unlikely to be good at showdown and I don’t expect to get bluff-raised very often. For example: A♣Q♣9♦7♦ on a flop: J♣7♣5♦ and a turn of 3♥.

When I have a pair, a flush draw, and over-cards that won’t make a straight for my opponent, this is a good spot for a second bullet. My hand is unlikely to be good at showdown and I don’t expect to get bluff-raised very often. For example: A♣Q♣9♦7♦ on a flop: J♣7♣5♦ and a turn of 3♥.

![]() Check-raising the turn for a bluff can be profitable against Ace-high boards when an opponent will try to represent AAXX quite often. I love to make this check-raise if I flop or turn a wrap. I’m credibly trying to represent middle sets with this play. For example, if the flop is A-J-5 and the turn is a 9, I will try to check-raise with KQT8, KKQT-type hands as well as QJJT and 7655-type hands at times.

Check-raising the turn for a bluff can be profitable against Ace-high boards when an opponent will try to represent AAXX quite often. I love to make this check-raise if I flop or turn a wrap. I’m credibly trying to represent middle sets with this play. For example, if the flop is A-J-5 and the turn is a 9, I will try to check-raise with KQT8, KKQT-type hands as well as QJJT and 7655-type hands at times.

![]() When I call a flop bet and the board pairs the turn, check-calling with a draw is a weak play. With premium wraps and flush draws, I mix in a few bluff-check-raises—this will balance the times I actually have the full house or set and help me realize value with my premium draws. If my opponent knows I’m capable of this play, they’ll check the turn quite often with mediocre hands and hope to get to showdown cheaply.

When I call a flop bet and the board pairs the turn, check-calling with a draw is a weak play. With premium wraps and flush draws, I mix in a few bluff-check-raises—this will balance the times I actually have the full house or set and help me realize value with my premium draws. If my opponent knows I’m capable of this play, they’ll check the turn quite often with mediocre hands and hope to get to showdown cheaply.

![]() When the board is locked-down on the flop (8-5-4 rainbow, 5-6-7 rainbow) and I called a flop bet with a draw, check-raising if the board pairs can be a great play—I try to represent a turned full house. For instance, on a J-T-7 rainbow flop, I check-called a flop bet with AKQT. The turn is 7♦. I check-raise representing JJXX, TTXX, J7XX, T7XX. My opponent will be hard-pressed to continue unless I’m representing a hand he actually holds (oops!).

When the board is locked-down on the flop (8-5-4 rainbow, 5-6-7 rainbow) and I called a flop bet with a draw, check-raising if the board pairs can be a great play—I try to represent a turned full house. For instance, on a J-T-7 rainbow flop, I check-called a flop bet with AKQT. The turn is 7♦. I check-raise representing JJXX, TTXX, J7XX, T7XX. My opponent will be hard-pressed to continue unless I’m representing a hand he actually holds (oops!).

![]()

With all cards dealt and no more drawing, the die has been cast—you either have the best hand or you don’t. The goal of river play is to respond as flawlessly as possible. Realize this: an omniscient opponent never calls a bet on the river—best hands raise and worse hands fold (or bluff). Obviously, there are times when you just have to call. I call with a hand that might be good if a raise will only get called by a better hand. Don’t be too showdown-oriented in PLO. Go with your reads. Bluff when it is right, and make some hero folds.

Before check-calling a bet on the river, I consider the possibility of check-raising. There are many hands in PLO that will fire a thin river value bet and call a check-raise.

Board: T♠8♠6♦2♣A♥

My hand: 9♣7♣6♦5♥

My opponent raised pre-flop from the Hi-Jack, I called from the big blind. We are playing very deep, 300 big blinds each. I check-call a pot-size bet on the flop because I don’t want to get tons of money in the pot without a backup to the higher nuts or a flush draw. On the turn, I fire a pot-size bet and get called. I felt sure he was on the Ace-high flush draw or a set. On the river Ace, it seems right to go for a check-raise. I think he’ll make a thin value bet with a hand like A♠ T♥ 5♠ 6♦. He’ll certainly bet AAXX and all sets, and he’ll pay off my check-raise with those hands as well.

On the same board with a river 5♣ (instead of the A♥), not much has changed in the hand—my opponent’s range wasn’t improved with that river card. Now, instead of going for a river check-raise, it is probably right to just fire at the pot again and hope to get paid off.

When I check-raise the river, I don’t check-raise the “pot”—that is too big a bet. I check-raise the river to about 2 to 2.5 times my opponent’s river bet. I need to be able to make this play with air as well as the nuts, and I don’t want my check-raises to be too expensive when I’m bluffing and I get called. Even a small check-raise can be hard for a player to call with a non-nut hand.

The advantage of check-raising on the river quite frequently is that it makes thin value bets and bluffs much less profitable for my opponents. I force them into “showdown mode” after pulling off a few of these. They become predictable and easy to play against.

If you’re playing against a “maniac” who check-raises the river quite frequently, you’d likely go into showdown mode with every hand, except the nuts and pure bluffs. You’d almost never bet two pair on the river because you wouldn’t want to face what could be a very difficult decision.

There are plenty of hands where I’ve check-raised the turn and the correct play is to go for a check-raise on the river for value. These are usually hands where I’ve “back-doored” the disguised nuts on a river card that probably helped my opponent’s range. For example:

A♣9♥8♣7♥

Flop: J♥T♥5♠

I raise from the cutoff, and get called from the button. I bet flop and get a call.

Turn: 2♣

I check-raise on the turn hoping to represent a set. My opponent calls.

River: 8♥

This is a great time to go for another check-raise. That card brought in almost all the draws, and my nut hand (straight flush!) is concealed. If I bet, I’ll only get a call from non-nut flushes and straights. By checking, I also give my opponent a chance to bluff with the naked Ace of Hearts.

There are plenty of hands where I know that my opponent was on a busted draw. This is incredibly common in PLO. In spots like this, my opponent will never be in a position to call a river bet. The only way to make money is to give them a chance to bluff. If they don’t bet the river, they weren’t going to call a river bet anyway, so I don’t lose value by checking in these spots.

It is rare for players to make thin value bets on the river in PLO. Usually, the ranges are extremely polarized—they’ll either turn up with close to the nuts or they’ll have air. Most of the time, two pair, small sets, and other weak hands are happy to just turn the cards up at showdown. Players who aren’t willing to bet on the river for thin value are just too easy to play against.

Getting value on the river with made hands can be surprisingly difficult. Opponents are unwilling to call even 1/2-pot-size bets with mediocre hands. By betting small on the river with all made hands and bluffs, I give them a chance to pay me off when I’m good and a chance to fold when I’m bluffing. Best of all, I’m bluffing at a price that is quite favorable to my overall expectation. After all, a 1/2-pot bluff on the river only has to be successful 1 out of 3 times to break even.

There are times when my opponent simply can’t be bluffing often enough to make a call profitable. I might have second or third nuts, but my hand can’t win. Folding full houses on the river isn’t much fun, but there really isn’t much option if I’m beat.

A♠ J♣ 9♠8♣

Flop: A♦A♥9♣ Turn: 6♣ River: T♦

I call a middle position opener from the big blind. I check raise after the flop and get snap called. I bet 2/3-pot on the turn and get called. I value bet 1/2-pot on the river and get raised—then puke.

There is almost no chance my hand is good even though I have the second nuts. Hero-folding is the winning option.

![]()

In PLO I’d suggest that you maintain a bankroll of 50 buy-ins or more. Higher variance demands a higher bankroll. It is also vital that you practice sound game selection, especially as the relative skill equals out at the higher levels and aggression increases. If you’re new to PLO, I recommend that you buy in short, maybe 40 big blinds or so. With this stack size, you’ll get to see lots of flops but you won’t be making that big a mistake after the flop with any of your drawing hands. In fact, if you’re the only player short-stacked in a game where most players are 100+ big blinds deep, you can have a significant advantage in the game. Practice some good hand selection, look for opportunities to put your stack to use post-flop, and see what happens. Have fun!