Introduction: From Theory to Global Framing

I now transition to another important element of my framework. In addition to an analysis of basic functionings and freedoms, there are various pillars that serve as evaluative criteria for assessing progress on disability rights. These five pillars are laws, rights, and norms; executive and budgetary support; administrative and coordinating capacity; attitudes and beliefs; and representation and participation. In the next two chapters, I will address each of these significant pillars and explore how they help frame a broader understanding of disability in the UAE and other parts of the world.

In this chapter, I explore the concept of legality and its role in disability justice in the context of the UAE. Legal sources help illuminate how cultural forces shape inclusive laws with respect to disability and access. In this sense, critical legal theory provides a useful framework to analyze various manifestations of legality that assume authority, politics, immutability, and neutrality are all-natural products of a legal order. Critical legal theory also questions the epistemologies and genealogies of intellectual history that dominate our ways of understanding legality.

Legalities and Access to Justice

Boyle (1985) addresses legal realism by explaining and critiquing modern European social and cultural schools of thought, whose impact continues to influence what we consider to be possible within legal systems. He proposes a definition of legal realism as the interpretation of legal systems as subjective entities whose inconsistencies are a product of legal actors’ socio-political-economic contexts. Marxist legal scholars condemned legal systems for the ways in which they functioned as a cultural apparatus of the superstructure, that is, the mechanisms by which the desires and needs of the ruling economic class were facilitated and coordinated. Furthermore, a tension arises in legal scholarship when attempting to study the nature of legality: on the one hand, there exists a structural master narrative that lawyers and all others only serve to articulate. On the other hand, legality may be interpreted as a phenomenological construct in which judges and other legal actors must symbolically and individually interpret and understand the codes and texts that, in turn, reshape legal systems.

Calabresi (2003) analyzes legal thought by categorizing the field into four approaches. In doing so, he asserts that legality must be studied in conjunction with other frameworks and disciplines. The legal system, Calabresi argues, perpetually integrates values exogenous to systems of legality via legislature or groups of people rather than purely by legal scholars. This gives an insight into the field of legal studies as neither predictable nor strictly coherent; the exogeneity of cultural and social values continuously alters the legal system through complex mechanisms not just limited to legislatures. The normative legal approach emphasizes the enforcement of rights via institutions, while neglecting the role of values within legality.

For people with disabilities in many parts of the world, institutions and the systems of legality have failed to adequately account for disability justice. Throughout the world, seeing justice or injustice in the context of disability becomes a key element in the process of individual or collective empowerment. As such, legal analysis should focus on the capacity of institutions to reform or reinterpret legal norms. Deemphasizing a positivist tradition and unveiling the role of norms and ideologies pushes for a separation of the study of rights from the study of value formation in legal systems. Understanding the underlying values of a legal system thus allows for a new range of institutional approaches to unfold.

Kratochwil (1991) takes a more specific approach, addressing the role of norms and rules on international laws. He claims that norms are shortcuts for human behaviors because they inform our reasoning processes. Kratochwil contends that laws are characterized by practical reasoning, which is in turn informed by normative contexts. He argues that norms are in place to “simplify choices for actors with non-identical preferences facing each other in a world characterized by scarcity” (13). Emphasis is on the ways in which the role of norms is analyzed by reshaping underlying assumptions and premises of previously utilized frameworks and practices. Thus, we can rethink the use of normative language and the rhetorical processes that inform it in order to understand the implications for the legal system. Kratochwil illustrates how the reasoning processes behind norms and rules are manifested in the production of laws both domestically and internationally. We must, therefore, reemphasize the role of normative and deliberate language toward the ends of producing inclusive and equitable laws.

Treaties and Sustainable Development Goals: CRPD and SDGs

Persons with disabilities continue to face discriminatory practices and systemic, attitudinal, and environmental barriers in police and judicial systems that prevent their full access to justice. There is also a lack of disability awareness among the police, legal officers, and laws that limit their legal capacity and equal recognition before the law. These pervasive barriers exist while persons with disabilities are at a higher risk of violence and discrimination and thus have higher needs for justice.

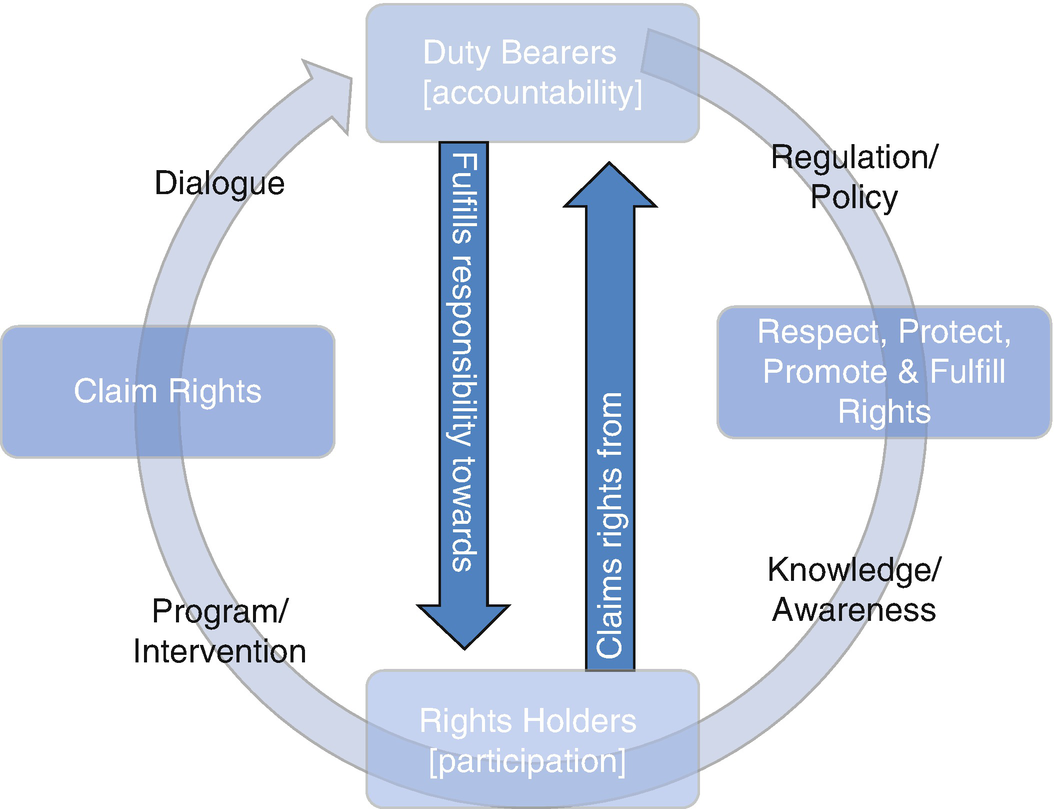

Diagram showing duty bearers fulfilling responsibilities to rights holders through regulatory policy, knowledge and awareness, program interventions, and dialogue. Through these steps rights holders can claim their rights

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) explicitly applies the right of access to justice in the context of disability. Specifically, Article 13 of the Convention directs State parties to ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others. It also includes the provision of specified accommodations that facilitate their effective role as direct and indirect participants such as the appropriate capacity building measure for those working in the field of administration of justice, including police and prison staff. Provisions of the CRPD beyond Article 13 are also relevant to access to justice. They outline requirements to ensure equality and non-discrimination; equal recognition before the law; liberty and security of the person; freedom from exploitation, violence, and abuse; and respect for private and family life.

The Lived Experience of Disability in the Context of Basic Functionings

Post-2013 Approach to Disability Inclusion

The remainder of this chapter illustrates how norms, discourses, social understanding, and the lived reality of persons with disabilities were shaped by the implementation of Federal Law No. 29. In the following sections, I look at how the implementation of the law as well as the commonly identified lack of means to enforce it, influenced a range of different sectors within UAE society in respect of the four basic functionings: health, rehabilitation, education, and employment. I then discuss how the implementation of the law impacted on the five basic freedoms: public and political participation, community and independent living, awareness, accessibility, and mobility.

Under the auspices of the My Community a City for Everyone initiative and in support of Federal Law No. 29, H.H. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE, issued Dubai Law No. 2 of 2014 for the protection of the rights of persons with disabilities in the Emirate of Dubai. The law was developed to demonstrate that persons with disabilities are entitled to all the rights prescribed to them, that they are respected and treated with dignity, and that their potential as empowered and productive members of society is recognized. The law calls on all concerned parties in Dubai to provide essential and basic services to all persons with disabilities such as the following: affordable healthcare and rehabilitation services; inclusive quality education at all stages; public services, which includes the use of roads and public transportation; facilitated access to public amenities; and ensuring that their surrounding environment is easily accessible. The Dubai law is also aligned and in accordance with the UN CRPD (2006), ratified by the UAE in February 2008.

The new law and “My Community” initiative stipulated the establishment of the Higher Committee for the Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to be led by H.H. Sheikh Mansoor bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum. The aim of this committee was to implement the articles of the local law and supervise the implementation of the Dubai Disability Strategy (DDS) 2020 that outlines the role of private and public sectors and civil society institutions in supporting and implementing this strategy along with its requisite objectives, goals, and strategic direction in transforming Dubai into a disability-friendly city by 2020. Government entities, committees, and offices in Dubai have combined their efforts to help develop successful, tangible, and practical steps to support the related legislations and laws.

In 2017, the UAE Government launched the UAE National Policy for Empowering People of Determination. The policy aimed to promote an inclusive society by referring to people with disabilities as “the determined ones” and establishing an advisory council along with dedicated official representatives in government institutions. Not dissimilar to the Dubai Strategy, the Six Pillars of the National Policy address health and rehabilitation; education; vocational rehabilitation and employment; outreach; social protection and family empowerment; and public life, culture, and sports.

From a Medical to a Rights Model in Health and Rehabilitation: Seeking a Cure or Ensuring Rights?

The CRPD stresses that persons with disabilities have a right to the same range, quality, and standard of free or affordable healthcare as provided to other persons. Additionally, the CRPD mandates states to provide health services needed specifically because of their disabilities. These include early intervention and services that aim to minimize and prevent further disabilities, which are especially important for children and the elderly (Article 25[b]). In contrast, Federal Law No. 29 limits most provisions of health to UAE nationals with disability categories that have been “qualified” and defined by the government. When a state demarcates disabilities as qualified or unqualified, they help define or limit the range of rights that are afforded to qualified individuals.

In signing the CRPD, the UAE was agreeing to ensure that health professionals in the UAE help raise awareness of the human rights, dignity, and needs of persons with disabilities through training and the promulgation of ethical standards in healthcare. In contrast, Federal Law No. 29 lumps the notion of awareness raising into early detection and diagnostic program development, remaining silent on much of the substantive and meaningful legislative content that could direct tangible change. An example of this can be seen in the area of protecting patient rights. During a focus group discussion, participants complained that the UAE has no strong provisions for patients’ rights. A young woman with a disability named Fatima stated that “if consenting family members and healthcare professionals have low expectations about a disabled woman’s ability to marry, she may be sterilized with the consent of her father.” Focus group participants thus stressed that such failures in legal protections of patients with disabilities needed to be addressed.

The Building of Inclusive Education Systems for All

Dubai Inclusive Education Policy Framework: Ten Standards for Inclusive Education

- 1.

Identification and Early Intervention

- 2.

Admissions, Participation, and Equity

- 3.

Leadership and Accountability

- 4.

Systems of Support for Inclusive Education

- 5.

Special Education Centers as a Resource for Inclusive Education

- 6.

Cooperation, Coordination, and Partnerships

- 7.

Fostering a Culture of Inclusive Education

- 8.

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting

- 9.

Resourcing for Inclusive Education

- 10.

Technical, Vocational Education, and Training (TVET) Higher Education and Post-School Employment

all children can learn and have the fundamental right to an education in the least restrictive environment providing equal opportunities;

school systems ought to be able to educate learners with appropriate support mechanisms; and

all benefit from a better quality of education, as improvements are realized.

A Journey from Social Burden to Human Capital: Attaining Gainful Employment

Although employment discrimination based on disability is prohibited under Federal Law No. 29, little has been done to spell out specific provisions. The language used in the law is ineffective—as indicated by phrases such as “Special needs shall be taken into account upon undergoing the tests of competency to have the job for people concerned with the provisions of this law.” The malleability of the language used here, that seems to encourage vague interpretation as a substitute for clear direction, is unfortunate and is detrimental to the supposed goals of the law.

Federal Law No. 29 does not characterize disability as a failure in agency but as a failure in the functions of the individual irrespective of their physical or social environment. The law is thus based on the medical model and stipulates that responsibility for employment issues should rest not with the Minister of Labor but with the Minister for Social Affairs/Community Development. It mandates the Minister for Social Affairs/Community Development with developing additional regulations with other concerned authorities.1 What is needed is increased coordination and discussion on the issue from a policy perspective.

Article 18 of Federal Law No. 29 clearly states that future legislation will regulate “the working hours, vacations and the other terms related to the work of persons of determination.” The law states that at the recommendation of the Minister of Social Affairs/Community Development, the Council of Ministers will at a future date discuss and decide upon the specific quota of persons with disabilities to be employed. These provisions are hinted at in Article 27 section 1(h) of the CRPD but disability rights scholars generally discourage the use of quotas.2

Dubai has an opportunity to protect the employment rights of persons with disabilities if it sets a standard definition that discrimination against persons with disabilities will not be tolerated and will be punishable and enforced by fines. Shortcomings of such programs are that although promotions do exist, protections do not. Ensuring the rights through fines, penalties, and administrative injunctions is the missing key. The law is silent on these points. As such, Federal Law No. 29 should be amended to include the proper incentives and penalties. Specific injunctions should be stipulated for monitoring and enforcing the implementation of the law.

The Lived Experience of Disability in the Context of Basic Freedoms

Post-2013 Approach to Disability Rights

Community and Independent Living in the Context of a Collectivistic Culture

Federal Law No. 29 is relatively silent on supporting persons with disabilities to live in the community with choices equal to others. In the UAE, persons with disabilities do not currently have access on an equal basis with others to housing and community-based services. The issue of independent and community living is based on the fundamental choices that persons with disabilities have or should have relative to where they live out their lives. In the UAE, people with disabilities are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement. Specifically, Article 9 specifies that individuals with disabilities should adapt himself or herself to integrate into society. The legislation characterizes the disability as occurring within the individual, irrespective of the individual’s environment, instead of characterizing the disability as a failure in agency of the individual due to barriers in the physical and social environment.

Federal Law No. 29, Article 9, takes the protectionist/rehabilitative approach to disability in contrast to Article 19 of the CRPD that is oriented around a rights-based model. Although Federal Law No. 29 could be improved by adopting the rights-based capability model articulated in the CRPD, the failure of the UAE to successfully implement Federal Law No. 29 in relation to independent living has more to do with the Council of Ministries and their delegates (established training centers and institutions) who are supposed to be taking the lead. Federal Law No. 29 should be amended to specifically provide for increasing choices to the manner in which persons with disabilities can live so that they may realistically be able to choose to form their own families or living near their families but independent of them.

Between 2006 and 2014, persons with disabilities did not live independently and were not being actively included in the community. This could be the result of the lack of support services and the cultural, political, and economic structures that define disability and citizenship. Like in other parts of the world, substantive citizenship in the UAE is afforded to an Emirati male that is employed or financially independent and has the capacity of forming a family. Substantive citizenship is more difficult for unmarried local women, older persons, and persons with disabilities. It is nearly impossible for foreign nationals to attain. This clear demarcation of citizenship and culture is indicative of the spectrum of salience between the international norms of the CRPD, the national norms of Federal Law No. 29, and the domestic norms of Arab culture and family tradition. Laws, culture, and politics all play a role in defining the social position of persons with disabilities and other marginalized groups. Their emancipation, therefore, depends on the restructuring of imaginaries and narratives around autonomy, human agency, tradition, religion, politics, and power. Awareness and attitudes are key factors in this social transformation.

The DDS recognizes the need to establish Centers for Community/Active Living (CCL) with the aim that such platforms may promote leadership, representation, and universalized disability awareness. To date, however, the charged Community Development Authority has not commenced the planning of such critical service delivery. This requires that it be able to promote self-advocacy and share knowledge of all available programs/opportunities via the ongoing exchange of information with others CCLs in the region and around the world. I certainly hope that by 2020, Dubai will embark, if only on a modest scale, on a center that can serve as a hub for exchange at a minimum and as a catalyst for empowerment and self-advocacy at best.

A Voice of Determination to the Once Voiceless: A Paradigm Shift in Disability Awareness and Advocacy

Article 8 of the CRPD on awareness-raising is considered by international disability rights scholars as being key to facilitating education, employment, accessibility, political and public participation, and other rights. As I have mentioned previously, Federal Law No. 29 heavily embraces the medical model of disability and thus does not characterize disability as a fundamental failure between the agent and their physical or social environment; instead, it characterizes disability as being the property of an individual. A person with a disability is understood by the law to be a deviation from the norm, thus needing rehabilitation to integrate into society. This is evident in the manner in which awareness raising is dealt with in Federal Law No. 29. The law does not raise this issue as a separate article but instead mentions it in the context of health. Article 11 states that awareness raising must concern itself only on the types of impairments instead of on the types of physical and social barriers that exist in society. The law thus understands the disability to be the property of an individual independent of their physical and social environment. Article 11 goes on to state that awareness raising should be the responsibility of the Specialized Committee on health. This statement is incongruous with the spirit of awareness raising that is reflected in Article 8 of the CRPD that states that awareness raising should be focused on providing equal opportunities in every aspect of life. Article 8 states that efforts should foster respect for the rights and dignities of persons with disabilities.3

Federal Law No. 29 should be amended to mandate specific efforts in the area of awareness such as awareness training and the role of the media in promoting rights and dignities but failed to do so. Rights promotion is raised in Articles 3 and 4 of Federal Law No. 29 and Article 39 states, “This law shall be published in the official gazette” (2006). Hence the law also fails to indicate who besides the Ministry of Social Affairs shall promote the law and specify the ways it is to be promoted.

In line with the explicit Dubai Law No. 2 statement that respective authorities “will have the duties and powers to: raise awareness in society of the rights of Persons with Disabilities under this Law and the legislation in force, and organize the awareness and education activities and campaigns required for this purpose,” the Executive Council’s Department for the Policies and Programs for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities launched a wide-scale awareness campaign designed to normalize disability and bring the lived experiences into the normal spheres of life—from home life and parenting to sports and cultural events, education, and work environments. Data from the Dubai Social Survey on the public perception of disability from 2015 to 2017 documents a 10% average increase in awareness of the issues people with disabilities face in daily life to the belief that people with disabilities should be included in society.

The declaration in 2017 by the leadership that people with disabilities ought to be addressed as People of Determination shook the community to the core. Evidence of the transformation was evident in language and signage, propelling retailers among others to put the statement of declaration in public spaces such as public beaches and malls, banks and schools.

Universal Accessibility and Mobility on Paper and in Practice

Article 23 of Federal Law No. 29 delegates the authority for promulgation of building codes and implementing them (i.e., monitoring and enforcement) to the Council of Ministers. However, the Council of Ministers has not taken action on this specific mandate and a national building code that would accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities was never developed. This is politically challenging since each emirate has near-complete autonomy on land use and real estate development. However, the failure to develop the building codes was in violation of Article 23 of Federal Law No. 29. The delay to draft a unified set of federal building codes would also postpone efforts to effectively monitor and enforce Federal Law No. 29. Without monitoring and enforcement, Federal Law No. 29 had no real efficacy.

Article 23 could have provided a framework for developing regulations that are based on inalienable rights rather than simply protections. Unfortunately, it does not. The drafters of Federal Law No. 29 did not see disability as a dynamic context-specific experience, where the environment played a key role in limiting an individual’s choices and opportunities. The drafters of Federal Law No. 29 understood disability only in medical or essentialist terms, placing the lived experience of disability squarely on the individuals irrespective of their environment.

Federal Law No. 29 also falls short in describing how access is to be achieved. By comparison, Article 9 of the CRPD specifically notes that the identification and elimination of obstacles and barriers to accessibility shall apply to a wide variety of areas. The CRPD also specifies that accessibility should include information and communication as well as other electronic services. Despite this, Federal Law No. 29 is silent on access to information, digital services, and other key aspects of the country’s future development.

Dubai Law No. 2 stands strong in its objective to provide “Accessible Environments to ensure that Persons with Disabilities enjoy all their rights under the legislation in force,” with explicit mention of access to places of worship and to public places; using roads and means of public transport. In an attempt to meet the obligations set in the law, the Higher Committee appointed the Dubai Municipality and the Road and Transport Authority to develop the Dubai Universal Design Code to define how the built environment and transportation systems in the Emirate will be designed, constructed, and managed to enable one to approach, enter, use, egress from, and evacuate independently, in an equitable and dignified manner, to the greatest extent possible, in line with the Universal Design concept.

In 2017, the Government of the Emirate of Dubai began to implement the Dubai Universal Accessibility Strategy and Action Plan (DUASAP). Fifteen relevant governmental and semi-governmental local entities in Dubai were mandated to prepare a three-year (2018–2020) sectoral implementation plan to retrofit existing buildings, infrastructure, and facilities to ensure a barrier-free and fully inclusive physical environment. The ten priority sectors include Education, Healthcare, Recreation, Culture and Arts, Sports, Religious Services, Transportation, Retail and Commercial services, Justice and Judicial Services, and Tourism. The Global Alliance on Accessible Technologies and Environments (GAATES), an international non-profit organization that promotes the accessibility of technologies and the built environment, was directly involved in the development of the policy. Using five strategic elements, Dubai has moved quickly to transform its infrastructure (built environment and public transportation) by 2020, ensuring that its code is enforced and implemented.

Mobility is mentioned in Article 20 of the CRPD and is referred to explicitly in Article 10 of Federal Law No. 29. Both articles cover assistive devices and mobility aids such as wheelchairs. Again, Federal Law No. 29 takes a medical approach in identifying a series of medical conditions that limit an individual without taking into account the individual’s environment. The CRPD approaches the right to mobility in a way that characterizes the disability as being relative to the individual’s social or physical environment. Federal Law No. 29’s emphasis on training should be directed not only toward persons with disabilities but also to staff, encouraging technologies that are facilitated at a time and manner of choice by the person with disability. Some efforts in this regard include innovations, hack-a-thons, and the deployment of wayfinding apps and specialized services such as Be My Eyes, or Aria that could transform mobility. In conjunction with the universal design standards, technology and mobility training for people with disabilities could open new possibilities for more equitable public participation for all.

Conclusion

Legal systems reflect cultural and societal norms that shape the laws that are developed with respect to disability and access. Reemphasizing the original theoretical approach to disability policy and rights, I have discussed the importance of basic functions and basic freedoms to inform my framework and examined how laws, rights, and norms are all affected by the basic freedoms and functions.

It is telling that between 2006 and 2014, disability was continuously characterized as a failure in the capacities of the individual regardless of their environment. Regulatory mandates were slow and ineffective, and by 2014, the Emirate of Dubai took on a unique role in spearheading the Dubai Disability Strategy to advance on the local level a range of disability programs and policies that would go beyond Federal Law No. 29 and provide a functioning framework for sustainable progress. Ultimately, the contrast in the way independent and community living is understood emphasizes the challenges of eliminating the protectionist approach to care and the cultural and institutional challenges of developing substantive citizenship for persons with disabilities based on inalienable rights and not a clientelistic social order dependent on relations of political patronage.

In many instances, Federal Law No. 29 falls short of assuring basic rights. For example, accommodations for those with disabilities are not defined and specific requirements or guidelines required by the CRPD are missing from the law. Federal Law No. 29 has, in practice, denied persons with disabilities the opportunity for an equal standard of education, an equal standard in employment, and an equal standard in access. This is not to deny the great advancements and achievements of Dubai and diminish its place among the most accessible and inclusive cities in the region, but rather to highlight a missed opportunity.

Dubai has made concerted efforts to align its strategic objectives with the global agenda. In fact, the leadership in Dubai has a vision and commitment to ensure that Dubai is transformed into a disability-friendly city by 2020. The inspired vision is to make Dubai an inclusive, barrier-free, and rights-based society that promotes, protects, and ensures the self-determination of people with disabilities or, as aptly reframed in October 2017 by H.H. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, “People of Determination.”

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.