CHAPTER 1

THE DAWNING OF A NEW WEDGE ERA

Most weekend players—and a surprisingly large number of Tour professionals—are working hard but failing to develop the simple short-game skills required to reach their true scoring potential. It’s not their fault, because what most instructors have taught about the short game for decades is, in a word, wrong.

It’s an exciting time in golf instruction. Old-school coaching—and its reliance on hunches and guesswork—is evolving into a modern, fact-based discipline. Credit goes to the massive and recent influx of science and scientific study in every area of the game, including the full swing, short game, putting, motor learning, and biomechanics. Many undeniable truths have been discovered, and just as many myths have been dispelled. Coaches are seeking and sharing knowledge based on research and testing instead of blindly accepting tradition, cutting the emotional ties that allow faulty theories to live beyond their time. We’ve come to that point in the short game. The earth is no longer flat.

This research revolution has been a long time coming. In 1994, when I first started teaching the methods that you’ll read about in this book, they were often met with a sideways stare from the golf establishment. I swam upstream for years, but remained steadfast as I continued to learn and grow in my beliefs. It has taken more than two decades, but the tide has turned. A new generation of research-savvy coaches, as well as many of the old guard that once balked at my techniques, have come to embrace my Finesse and Distance Wedge Systems, which you’ll become familiar with in this book as the “how to” short-game methods. Truth be told, I didn’t invent these techniques—great players have used them since the dawn of the sand wedge. But they were closely guarded secrets known and shared by an elite few. I was just lucky enough to come across some of these individuals and, through four serendipitous events and a lot of hard work, systematically unlock them.

In Your Short Game Solution, I describe with simplicity and clarity what you need to do to make these methods your own and develop a world-class short game. In addition, I’ve created a practice plan for you to follow so that you’ll not only make a quantum leap in performance, but sustain it over time. With just a little discipline and focus, you’ll develop the confidence, swagger, and shotmaking flair that all great short-game players share.

ORIGIN OF THE SYSTEM

To truly absorb what lies ahead, I think it’s important to understand the roots of my beliefs. How did the shortcomings of a failed mini-tour player come to figure into your improvement plan? Why is discipline more important to succeeding than a huge investment in time? How did a little-known coach from a flyover state steadily become one of the most sought-after short-game experts in professional golf, with a client list that now includes more than eighty PGA and LPGA Tour players? The answers lie in the tangled history of my wedge systems, a must-read tale that will help ignite your quest for your lowest scores.

Part 1: Meet the Sieckmanns

I grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, as one of three sons in a golf-crazed family. My oldest brother, Tom, was nearly ten years my senior and played golf at Oklahoma State University. I was seven when he went off to college and not that much older when he left O.S.U. early to compete on the Asian and South American tours, beginning in 1977. Tom was sort of the “shining light” in our clan. His professional career would eventually span seventeen years, and he notched nine victories worldwide, including the 1988 Anheuser-Busch Golf Classic on the PGA Tour.

I was proud of Tom, and some of his skills must have rubbed off on me, because I shot 76 as a ten-year-old and won quite a few tournaments as a junior with minimal formal coaching. As such, I did what felt natural. I had very few swing thoughts and played with a lot of confidence. Golf was fun then—zero fear, all dreams. I parlayed my instincts into several good showings and an athletic scholarship to the University of Nebraska. As my journey in golf continued, Tom and I reconnected both as brothers and competitive golfers. There was a lot I could learn from him. Little did I know what was in store.

Part 2: Meet Seve Ballesteros

In addition to being a great golfer, Tom is smart and introspective. An avid reader of history with a keen mind for finance, he was anything but your typical pro athlete. Among other things, he taught himself Spanish. I’m sure it was more like “Spanglish,” but that didn’t stop him from speaking it during playing stints in South America and Europe. Serendipity struck for the first time when Tom’s blind disregard for proper linguistics caught the ear of a young Spaniard at the 1977 Colombian Open in Medellín. Barely nineteen years old, Seve Ballesteros heard Tom’s broken Spanish and felt comforted. After all, he was five thousand miles away from home and Spanish was the only language he knew.

“Seve and I just kind of hit it off,” remembers Tom. “He appreciated that I was trying to speak Spanish and that I was interested in the short game. Even then he was already the best. The world just didn’t know it yet.” Ballesteros would forever cement his place in the public consciousness with his victory at the 1979 British Open at the age of twenty-two. By then, my brother and the young Spaniard were already good friends, working on their short games together and playing practice rounds whenever they could.

In 1984, Tom qualified for the U.S. Open at Winged Foot. I remember the phone call from him like it was yesterday: “Come meet me at the Open. You have to see Seve Ballesteros in person.”

I was nineteen years old. It was my first trip to New York, my first time at a major, and I was inside the ropes, caddying no less. I felt a bit out of my league, so I kept my head down and focused on being the best caddy I could. Tom played nine holes by himself on Monday afternoon. On Tuesday, we paired up with two of his friends. One was Seve, who oozed confidence and competence. As the saying goes, men wanted to be him and women wanted to be with him—and you could tell that from a hundred yards away. The other friend was second-year pro Tom Pernice Jr., whom Tom had befriended on the Asian Tour. Like my brother, Pernice loved to practice short-game shots and hung around Seve every chance he could.

“When I first met Seve, he was only twenty years old and he’s hitting shots like I’ve never seen,” Pernice recalls today. “He hit softer shots with his 3-iron out of the bunker than we could with a sand wedge. During practice rounds, we’d put him in situations he had never seen and he’d pull off a ridiculous shot on the first attempt.”

That day at Winged Foot, the two Toms played Seve and Wayne Grady in a $20 Nassau. “Tom and Tom have no chance,” I thought, but they managed to win the total and several presses. Seve was not amused. After the round, I accompanied my brother into the players’ locker room. We sat down to eat lunch and were joined a few minutes later by Seve. He was a gentleman and made a point to include me in the conversation, at one point lecturing me not to use “being young” as an excuse for failing. (I had missed the cut at the second stage of U.S. Open qualifying just two weeks earlier.) Needless to say, I became a Ballesteros fan for life on the spot.

My brother, Tom (second from right) playing his Tuesday practice round at the 1991 Masters with Seve Ballesteros (far right) and José María Olazábal (center). Tom’s friendship with Seve lasted thirty-four years, and much of my Finesse and Distance Wedge Systems are based on my brother’s and Ballesteros’s techniques. (I’m in the caddy uniform, far left.)

Part 3: On My Own

I played well for the Cornhuskers in spurts, especially during my freshman and sophomore seasons, but it was obvious, even then, that I would need to improve my short game to realize my dreams. In hindsight, it was the beginning of the end. Why I didn’t recognize or pay particular attention to what Seve and my brother were doing technique-wise at Winged Foot, and during several encounters thereafter, I’ll never know. I had the best short-game player in history standing right in front of my face, and I learned nothing. Instead, I bought and read books and magazines, falling victim to the blind hunches, guesswork, and accepted myths of the teaching establishment:

A chip is just a miniature full swing.

Keep your head still.

Keep your lead arm straight and don’t ever let the clubhead pass your hands.

The tips looked good on paper, but they certainly didn’t help. My response when they failed was to practice even harder and longer—surely the problem was with me and not the establishment. I was twenty years old and, suddenly, my growth as a golfer had flatlined. Even worse, I was studying myself out of my natural gifts.

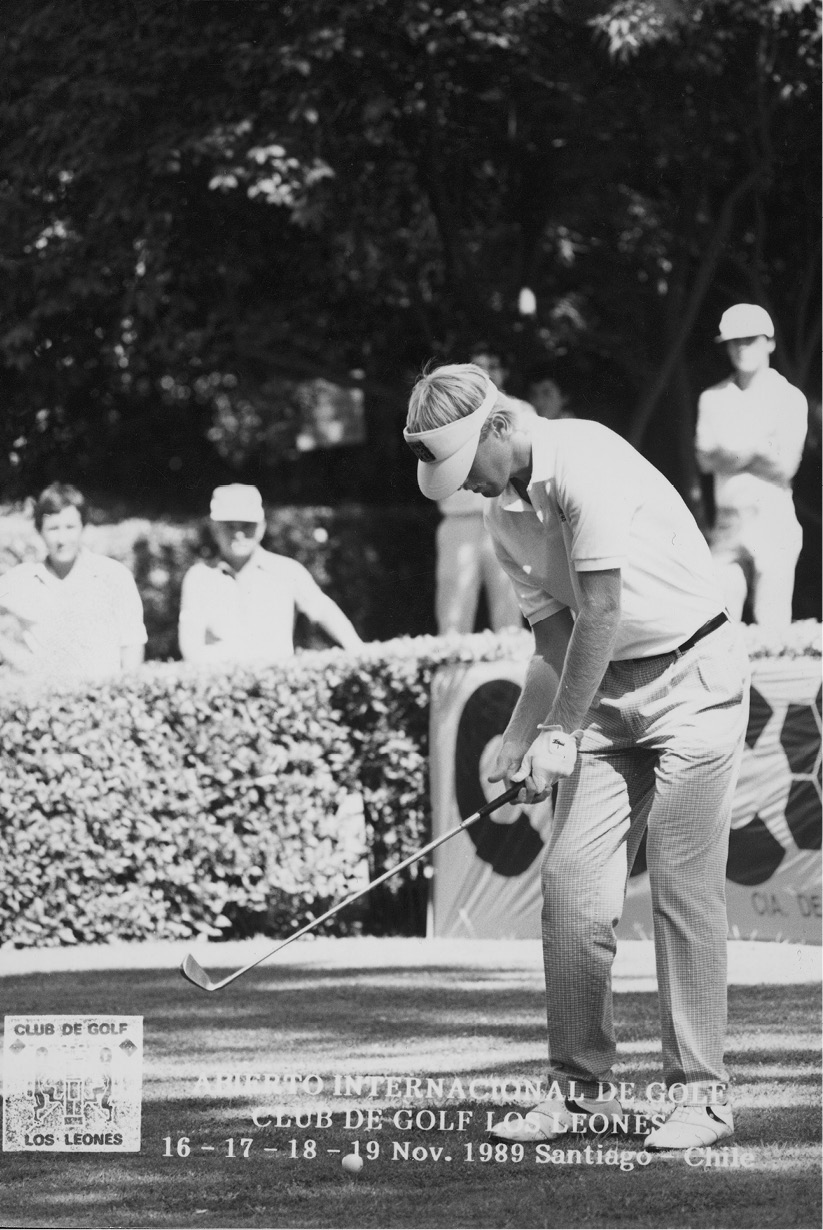

Nevertheless, I followed in my brother’s footsteps after graduating and set out to compete on the South American Tour. It was 1989; five years had passed since my lunch with Seve at Winged Foot. After competing in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile and failing to qualify for the 1990 PGA Tour season (my first of three Q-School busts), I flew to the Philippines for the first of eleven tournaments over the span of eleven weeks on the Asian Tour. I knew I was struggling, but I was confident that if I worked hard, something would eventually click and take my game to the next level. The click turned out to be a “clank.” I labored in Asia for nearly three months. My poor performance around the greens persisted like a bad houseguest. At some point, I stopped feeling comfortable over the ball. Shots I had hit day in and day out since I was a little boy suddenly felt foreign. I started to fear little shots, and as a golfer there’s nothing worse than fear. So I did the only thing I knew how to do: work harder. While the rest of the players went sightseeing, I emptied shag bags hitting pitches and chips under the hot Asian sun. I practiced nonstop—no deviation, no routine, all technique.

Apparently, working hard on the wrong things the wrong way isn’t much of a strategy. The doubts I had about my game increased with every missed cut and 50th-place finish. I’d replay poor chips and pitches in my head at night and wonder what was wrong with me. Despite my sincere efforts, I was getting worse, not better.

In hindsight, I had hit the perfect trifecta of failure: I was working with faulty information, I was training ineffectively, and I was a malicious self-critic. What I’d give to know then what I do now, but obviously that’s not the way life works.

The life of a traveling Tour player can be a difficult one, especially when you’re filling up passports in the process. Add in poor results and stretching every dollar so you can play the next event, and it’s a life you don’t want, dreams be damned. I hung in there for four years. In 1992, in a hotel room in New Delhi after posting yet another 50-something finish, I quit. Enough was enough. I was ready for a new chapter in my life. I flew home to Nebraska.

Part 4: The Pelz Experience

Not long after my plane hit the tarmac at Eppley Airfield in Omaha in the late spring of 1992, I proposed to my girlfriend, Michele Neal, and took a full-time coaching job at the Dave Pelz Short Game School in Austin, Texas. It was a reunion of sorts; my brother saw Dave a lot over the years, and I’d often tag along to Austin to watch them work, or go by myself to practice when it got too cold in Omaha. I knew Dave well, and was lucky and thankful that he thought enough of me to give me a new beginning.

I worked for a couple of years in Austin and another at the Pelz School in Boca Raton, Florida. I matured quickly as a coach, and I owe much of my growth to Dave. Although today we don’t see eye to eye on a lot of things about the short game, he was the first person to challenge me to think critically about mechanics and to understand how people learn and train most effectively. He’s a great coach and an outstanding person, and I owe him an awful lot.

Part 5: The Ponte Vedra Experience

I worked for Dave through March of 1994, until one of my closest friends and former sponsors, Steve Shanahan, established a partnership with my brother in the development of a new course in Omaha and asked me to direct the golf academy. Working for Pelz had been great, but this was too prime an opportunity to pass up: I’d get to be my own boss to some extent, teach my own methods, and raise a family in my hometown. Between farewells to Dave and the late-spring grand opening of my new academy at Shadow Ridge Country Club, I had two months of downtime. With nothing to do but go to the beach, I accepted an invitation to caddy for my brother at the Players Championship in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. Serendipity had struck again.

Given another chance to walk among the greatest players in the world, I wasn’t going to waste it this time. I arrived at TPC Sawgrass in March of 1994 with Tom’s bag on one shoulder and a video camera on the other. With a thirst for short-game knowledge, I filmed every great short-game player I could find. In addition to my brother, I saw Raymond Floyd and Corey Pavin, smoothly hitting chips onto a practice green. There was Greg Norman, working on his bunker technique—and making it look easy. On the range: Wayne Grady and Jodie Mudd dialing in wedge shots from every distance. And of course, Seve—The Master—doing everything. Tom played and practiced with Seve on Monday and Tuesday, and I recorded almost every short-game swing Seve made, probably to his chagrin. I can still recall him hitting practice shots out of the pot bunker behind the fourth green. He splashed five of the softest spinning bunker shots I had ever seen, all finishing within a yard or so of the pin. When he put his club in his bag, I about fell over when I saw that it was a 56-degree sand wedge and not a lob wedge. Once again, he had made the near impossible seem mundane.

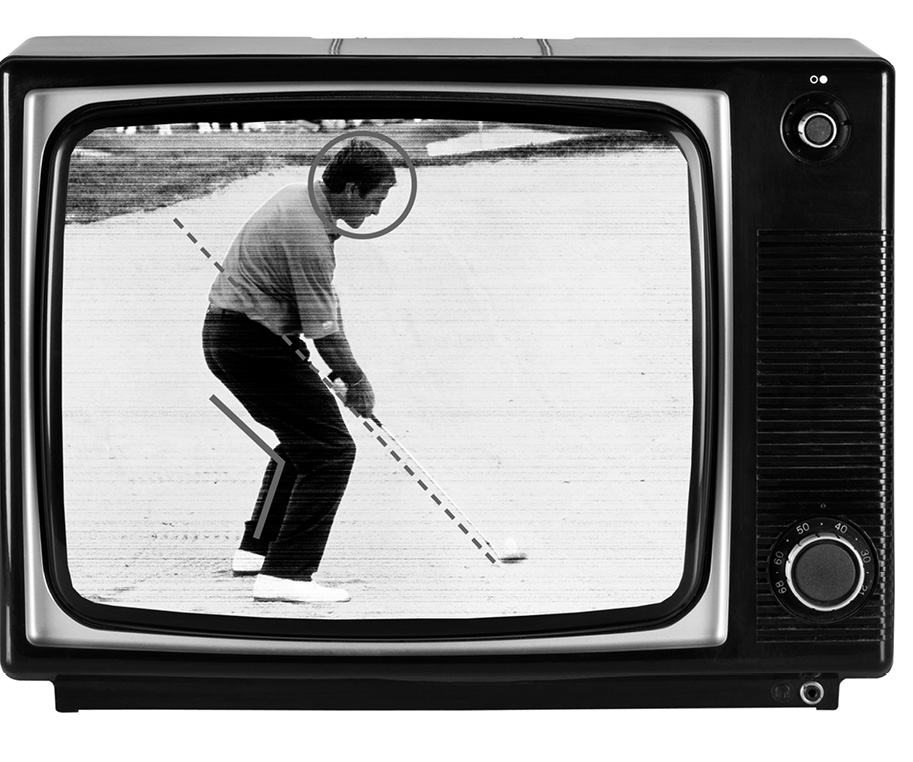

Tom finished the tournament twenty-four shots behind Greg Norman, who won the event by four over Fuzzy Zoeller. It wasn’t a great week for my brother, but it was the start of something special for me. Even after teaching the short game for three years, I didn’t feel like I really understood what great wedge play was all about, but my varied experiences had given me some insight on what questions to ask. Plus, I knew I had some one-of-a-kind material to study. As soon as my wife and I moved into our new apartment, I watched the videos. I decided that the best place to start was to wipe the slate clean, assume nothing, and simply catalog what great players did in every phase of the short game. After doing this for several weeks—dry-erase-marker lines all over the TV—some swing commonalities became apparent. After several more weeks, I could see how those commonalities were fitting together. “If this is what the best players in the world do,” I thought, “then this is what I’m going to teach, regardless of what others think.”

The videos both surprised and sickened me. They proved to me that everything I had ever been taught about short shots around the green—and practiced to exhaustion—was wrong. Things like “lean your weight toward the target at address,” “keep your head still,” and “don’t break down or let the club pass your hands.” I had hours of film showing the most talented wedge players on earth making these “mistakes” over and over. That was only the beginning; I drew plane lines, measured rhythm, and tried to quantify everything I could about both club and body movement. After a month, I pared what I saw on screen down to five big-ticket items and developed a way to understand how they fit together: my Finesse Wedge System (the Distance Wedge System came later). I have refined it every year since and believe in it more deeply with every coaching experience.

A frame-by-frame analysis of the wedge swings of Seve Ballesteros and other elite players proved beyond a doubt that what’s often taught about the short game is wrong. For me, the secrets were on my TV screen.

Part 6: The Finesse Wedge System on Tour

For the next three years, I taught my system exclusively to the members at Shadow Ridge C.C. I didn’t publish my findings or speak about them with other teaching professionals. Serendipity struck a third time via a phone call from Tom Pernice Jr. in 1996. (In addition to being one of my brother’s best friends, “TP” and I played together in Asia and had also developed a friendship.) TP was playing the Hogan Tour that year (now the Web.com Tour) and was driving from an event in Wichita to another in Sioux City, Iowa, taking I-80 straight through Omaha. He was struggling mightily with his putting and, knowing I had worked for Dave Pelz, asked if I would take a look at him. I remember him misaligning his putter drastically on a straight-in six-footer at the start of the lesson, but as talented and hardworking as he was, it didn’t take long to get him back on track. He called a month later and asked if I’d come to the Tour stop in Boise, Idaho, for another session. It was an interesting proposition, and I wanted to do it, but the numbers didn’t add up. It would cost more in airfare, lodging, and three days of lost lessons at Shadow Ridge than what TP could pay me. I eventually agreed, but I asked him if he could find me some other players to work with in order to offset my expenses. Thankfully, a few other players said yes. One of them was Charlie Wi, a recent graduate of UC Berkeley who was playing in his first year as a professional. Just like that, my life as a Tour instructor had begun. I’ve coached Tom and Charlie continually since 1996. Their loyalty to me has been immeasurable, and it has been a symbiotic relationship, for sure. Tour players ask tough questions, and they’re so skilled that if you tell them the right things, they improve immediately. On the flip side, there’s no faking it and nowhere to hide if you get it wrong. Coaching on Tour has taught me to think things all the way through, to be detail-oriented, prepared, and certain. I love the challenge it presents, and while I have many pro clients now, TP has been the difference maker. He studied and practiced with Seve for years, so he was already doing much of what I taught, and his enthusiasm and knowledge of the short game is unmatched by any player I’ve ever met. There’s no doubt that I have learned more from him over the years than he has from me. As such, traveling has become a paradox; I don’t particularly care for all of the hassles, and I hate being away from my family (I’m on the road about 150 days a year), but it’s essential to my continued growth. Every time I leave my little patch of grass at Shadow Ridge to work on Tour, I pick up something new that helps me get better at my craft. Unfortunately, I have learned to love packing my suitcase.

Part 7: Soaring with Science

Despite working with an amazing client list, I toiled in relative anonymity my first thirteen years as a Tour coach, but I was satisfied with my career. Between my Academy at Shadow Ridge and raising two children with my wife, my plate seemed full but things were about to change. I don’t know how many times serendipity can strike the middle of Nebraska, but it happened for a fourth time on my journey as a coach by way of an unexpected phone call from Dr. Greg Rose, co-founder of the Titleist Performance Institute (T.P.I.). Dr. Rose asked if I would be willing to work with PGA Tour player and Titleist staffer Ben Crane on his wedge game. I knew both Ben and Greg by reputation, but I had never spoken with either. We met a week later at the Madison Club in La Quinta, California. I started the session like I do with any serious student by providing them with a copy of my Short Game Notebook, a manual detailing all of my beliefs and concepts. (As a former player, I know there’s zero room for doubt or miscommunication when you’re competing for a paycheck, and the Notebook leaves nothing to chance.) We worked for two days straight and got along beautifully. More important, Crane’s wedge game improved. We worked again three weeks later at T.P.I., the day before the first round of the 2010 Farmers Insurance Open at Torrey Pines. Crane won—his first PGA Tour victory in almost five years—and led the field in scrambling at 89 percent. (The average scrambling percentage on Tour is around 57 percent.)

I took it that Dr. Rose was impressed, because he delivered several other Titleist staff players to me over the ensuing weeks. First Charley Hoffman and Brad Faxon, then Tom Purtzer and LPGA Tour player I.K. Kim. Eventually, I had to ask: “Why me?”

The answer, according to Dr. Rose, was a small paragraph I had written in my Notebook describing the correct sequence of events for a finesse wedge shot and what problems are created if you get it wrong.

Dr. Rose and T.P.I. co-founder Dave Phillips had already helped crack the kinematic sequence in full swings (the golf motion that proves the hips reach maximum speed first on the downswing, followed sequentially by the torso, arms, and finally, the clubhead). For many years, T.P.I. measured every Titleist golfer on both power swings and short-game swings, such as a 10-yard chip. By 2009, it had hundreds of Tour players in the system and had the full swing nailed. The problem? The data from the 3-D motion-capture system the company used to measure wedge swings didn’t match up with the data generated on power swings. “With the short swing, we were still unsure about what the data was showing,” says Rose.

That’s because in a world-class finesse wedge swing, as I wrote in the Notebook, it’s absolutely essential that the club starts down before the hips rotate, which is the reverse kinematic sequence of a power swing. Without the correct sequence, it’s impossible to use the club correctly or to produce consistently solid contact (more on this in Chapter 4). My paragraph describing what great wedge players such as Seve Ballesteros do and why they do it matched Dr. Rose’s scientific data to a T.

“James knew it,” says Rose. “He knew it almost twenty years ago, before the term ‘kinematic sequence’ and 3-D motion capture were even around.”

Dr. Rose and I ultimately helped each other. He got the answer to his short-game data problem, and by independently validating through science what I had carefully observed analyzing hours of video, he helped me gain notoriety as one of the premier short-game experts in the world. Over the years, I’ve shared these findings and other insights with more than 80 PGA and LPGA Tour players. Now, it’s time to share these findings with you. The mistakes I made and the failures I endured as a golfer aren’t limited to those who play for money. I see them everywhere and at every skill level. No other part of the game is littered with as many misconceptions—or is more poorly taught—than wedge play. That’s why I’m excited that you’ve purchased Your Short Game Solution. The revolution is nearly over. Science has won, but it’s time to get the message out. Let your journey begin!