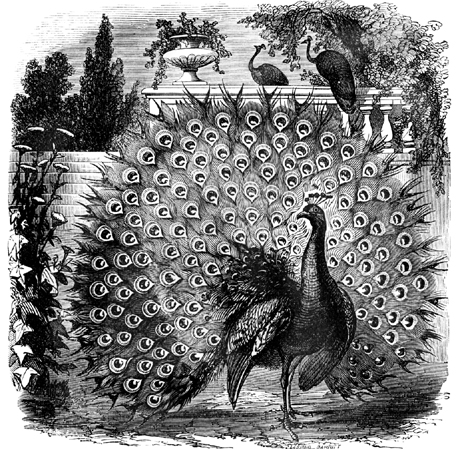

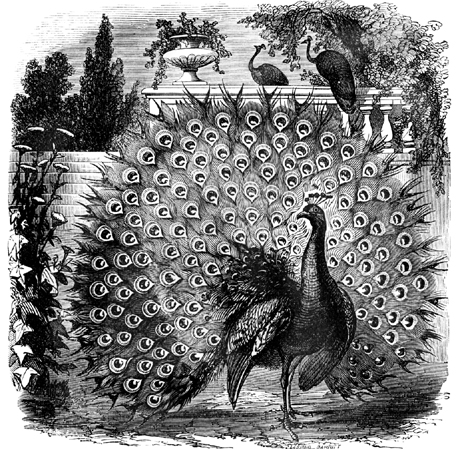

The male bird has iridescent blue-green plumage and a head crest, and the female is brown and without long tail feathers. The mating display, where the male fans out its feathers and utters distinctive calls to attract the female, is spectacular.

Despite the fact that its native home is in Asia, the peacock is a familiar bird throughout much of the world, having been introduced to Europe via ancient Greece. Its beauty and haughty demeanour can hardly fail to catch the eye; appropriately enough, in heraldry, a peacock displaying its tail feathers is described as being ‘in his pride’. Given its flamboyance, it’s easy to understand how the birds have tended to become status symbols, familiar sights in the grounds of many palaces and stately homes.

To the ancient Greeks, the peacock was held to be sacred to Hera, who was married to Zeus, king of the gods. Zeus was extremely promiscuous (see, for example, the CUCKOO and SWAN for further stories about him) and quite unable to resist a pretty woman, be she goddess or human. At one time, he was greatly attracted to a young woman called Io, so much so, in fact, that Hera became highly suspicious. In an attempt to allay her jealousy, Zeus turned the unfortunate Io into a heifer (how the once-beautiful Io felt about this transformation we are not told). Hera, however, was not at all mollified by this gesture, and she commanded her servant Argus, who had one hundred eyes, to keep a close watch on the situation. Zeus retaliated by ordering his messenger, Hermes (god of travellers), to lull Argus to sleep with beautiful music and then kill him. Greatly distressed by this, Hera took some of Argus’ eyes and placed them on the tail of her favourite bird in commemoration of her faithful servant.

Even though peacocks are famous for their beauty, a good deal of negative superstition persists to this day regarding the possession and use of peacock feathers. Many actors, for instance, believe that to have peacock feathers on the stage will bring disaster to a play. In some places, it was formerly thought that peacock feathers in a house would either result in any spinster who lived there remaining unmarried or in general bad luck. Such ideas appear to have their root in the concept of the evil eye – the belief that some individuals had the power to harm or even kill with a glance. That said, it does seem to be the case that this is a very late superstition – probably arising at some point in the mid-nineteenth century. Certainly, many people in the West were and are happy to wear peacock feathers, while in China, for example, peacock feathers were worn regularly at official functions. During the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907), many districts paid their tributes to the emperor with peacock feathers. He, in turn, awarded them to officials, both civil and military, for their good conduct and long service. The feathers were graded according to the services being recognized, and were classified as ‘one-eyed’, ‘two-eyed’ and ‘three-eyed’, ‘flower’ and ‘green’ feathers.

In their lands of origin – the East, and India in particular – peacocks are regarded very affectionately, their loud screeches being regarded as a useful warning of approaching predators, such as tigers or leopards, or of more general danger. One legend tells how a general of the Chinese Qin dynasty, defeated in battle, took refuge in a forest in which there were known to be a great number of peacocks. When his pursuing enemies finally reached the forest, all was quiet, so they assumed that he could not have hidden there; if he had, the peacocks would surely have betrayed him. In time, the defeated general became a king, and to honour the peacocks that had protected him he decreed that in future their feathers should be awarded as a mark of bravery in battle.

One rather strange belief is that the peacock is ashamed of its large black feet. Robert Chester in Love’s Martyr (1601), for example, refers to:

The proud sun-loving peacock with his feathers

Walks all alone, thinking himself a king

But when he lookes downe to his base blacke feete

He droops, and is ashamed of things unmete.

Similarly, the medieval Persian poet Azz’Eddin Elmocadessi describes:

The peacock wedded to the world

Of all her gorgeous plumage vain

With glowing banners wide unfurled

Sweeps slowly by in proud disdain.

But in her heart a torment lies

That dims the brightness of her eyes

She turns away her glance – but no

Her hideous feet appear below.