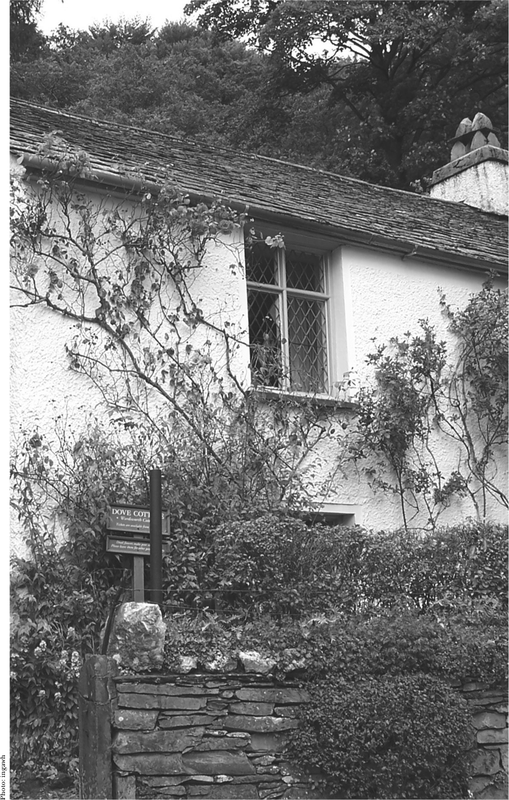

DOVE COTTAGE, GRASMERE, CUMBRIA – WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770–1850)

Dove Cottage was home to two distinguished writers in succession. In 1799 William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy rented it and subsequently filled its few rooms with friends, a dog donated by Sir Walter Scott, and so many children (by William’s wife Mary) that he moved the whole household out to bigger premises in 1808. At that point Thomas De Quincey, who had loved the cottage as a visitor and Wordsworth acolyte, moved in with his own wife, family and dog. There’s not much of Quincey in the cottage today. A portrait now stands above the mantel in what was Dorothy Wordsworth’s bedroom, with some poppy stems on the mantelpiece in a tribute to his famous opium ‘eating’, and there’s a large circular scorch mark on the landing where Margaret De Quincey put down a bucket of hot coals to tell her children to stop squabbling. But the rest of this cottage, set back from the main road to Keswick, is essentially a shrine to William Wordsworth.

Wordsworth was a revolutionary poet who brought the subject matter of poetry back to human beings but ironically he was loved more as a writer than a person. Byron and Keats in particular admired his poetic achievements, while complaining that the older man was too full of himself.

I’ve always felt that Wordsworth is one of those writers whose influence has been so completely absorbed since his death that it’s difficult to see now why he was considered so important. (maybe D.H. Lawrence is another.) These days the eminent Sage of Grasmere is the ‘Daffodils’ man, the ‘Lucy’ poet, and the rhymer who thought that earth had nothing more fair to show than the view from Westminster Bridge. Poor Wordsworth, it was his collaborator in Lyrical Ballads – and frequent house-guest – the laudanum-addicted Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a long poem that is still read with enthusiasm today (unlike William’s work). Indeed, when I visited the Wordsworth Museum Shop at Dove Cottage, Grasmere I saw that CDs of Ian McKellen reading The Ancient Mariner were selling well, while recordings of Wordsworth’s magnum opus, The Prelude, were largely ignored.

After Coleridge stayed with the Wordsworths in 1810, William badmouthed him to a mutual friend, Basil Montagu, warning him of Coleridge’s noisy, opium-induced nightmares. Unfortunately Montagu passed on his exact words: ‘Wordsworth has commissioned me to tell you that he has no hope of you, that you have been a rotten drunkard and rotted out your entrails by intemperance, and have been an absolute nuisance in his family.’ No wonder their friendship soured. I also feel it was rather mean of Wordsworth to take on the job of British Poet Laureate in 1843, collect his stipend for seven years but never come up with a single verse.

I suppose it’s naive of us to expect great artists to be nice people. Nice has nothing to do with creativity. Even so, Wordsworth is probably the last literary great I’d invite to a dinner party. According to many accounts, he would dominate the conversation and talk entirely about himself. At least Byron would have made everyone laugh, albeit while trying to seduce my wife.

Bearing Wordsworth’s temperament in mind, I wasn’t best disposed towards him when parking opposite the Daffodils Hotel in Grasmere. I went first to look at St Oswald’s church across the River Rydal, where the Wordsworth family tombstones are located. They are lined up in the churchyard overlooking the new ‘Daffodil Garden’ where you can buy Wordsworth Daffodil Bulbs to take home with you. Nearby a pink-painted shop selling canvas bags invited customers to ‘Feel Free to Wander Lonely, or as a Crowd’, and I found that the dining room at the Wordsworth Hotel is called ‘The Prelude’. As a result of all this commercial exploitation, by the time I got to Dove Cottage I was beginning to feel quite sorry for poor over-marketed ‘Turdsworth’, as Byron referred to him.

Up until 1793 the cottage had been a public house known as the Dove and Olive Branch. When Wordsworth and his sister rented it, the downstairs floors were flagstones (typical of an English country inn where ale needed to be regularly mopped up). The whole place, its wood panelling and casements, its rickety staircase and cuckoo clock, has been well preserved thanks to the Wordsworth Trust. In 1890 they bought Dove Cottage to create a museum. The museum itself is now housed in a separate modern building and the cottage is kept as an approximation of Wordsworth’s home (1799–1808).

The best room in the cottage is undoubtedly Wordsworth’s study on the first floor, which would have originally had views of Grasmere (but some tall late nineteenth-century houses put paid to that). Wordsworth’s chair – called a ‘cavalier’ because you could sit in it without removing your sword – is on display in the middle of the room. Here he would rest a pad of paper on its wide arms to write. Having taken many examinations in his university career, Wordsworth considered the desk ‘an instrument of torture’. A glass cabinet nearby displays his ice skates (Wordsworth claimed he was such a good skater he could inscribe his name in the ice) and his suitcase is open on a table top. The case is tiny, but the poet believed you only needed a nightshirt, a change of shirt and a notebook when travelling. You can see that he had lettered his name into the lid. Unfortunately Wordsworth started off with characters too big so that by the time he was squeezing what remained of his name into the right-hand edge, he was reduced to ‘William Wordswort’. So much for inscribing his name on a lake, I thought.

Here in this room the poet wrote – among many other pieces – the Lucy poems, ‘The Ruined Cottage’, ‘Daffodils’ (aka ‘I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud’), the ode ‘Intimations of Immortality, Composed upon Westminster Bridge’ and the sonnet ‘The World is too much with Us’, one of his attacks on an increasingly industrialised society beyond the Lake District. He also worked on early drafts of The Prelude, a poetic autobiography that eventually ran to fourteen volumes.

The open-sided chair suggests a writer of energy who would need to get up frequently and pace while writing (Wordsworth was a passionate walker), while the skates remind me of Wordsworth’s vanity. As for that suitcase: the inscription speaks of vanity and fallibility. The fact that Wordsworth would also leave this room only to go downstairs and complain to his sister, wife and sister-in-law that they needed to keep the children quiet also fails to endear Wordsworth to me.

I came away feeling that Dove Cottage definitely provides an insight into William Wordsworth, man and poet. I can’t say I liked him any more as I left, but I did feel more connected with the man and his poetry by seeing where he wrote so much of it.

As I left, however, I’m afraid I bought The Ancient Mariner CD, not a recording of The Prelude.

THE PARSONAGE, HAWORTH, WEST YORKSHIRE – CHARLOTTE BRONTË (1816–55)

Some places where great literature was written can disappoint because they seem so unrelated to what went on in the author’s head at the time. Occasionally the place has changed radically; sometimes the writer was occupying an inner landscape so personal and absorbing that he or she ignored the material world in which the writing was taking place. But then there’s Haworth.

The parsonage at Haworth is to Brontë fans what Bayreuth is to Wagner’s acolytes. Here is a landscape where you can believe the art was created. More exciting than anything that happened in Bayreuth, however, here is the landscape that literally inspired the writing.

Haworth sits on a ridge above the Bridgehouse Beck, a stream that has carved out a steep ravine in the West Yorkshire moors. In 1778 a new, plain Georgian-style parsonage was built at the top of the village, just above the church of St Michael and All Angels. In 1820 the new incumbent Patrick Brontë arrived with his wife and six children to take up the perpetual curacy.

The three youngest girls, who would go on to be Britain’s first family of literary geniuses, were Charlotte (aged four), Emily (aged two) and Anne (newly-born). There was also a brother, Branwell (then aged three) who would drink himself to death by the age of 31, and two older sisters who would die at a cheap boarding school five years after the move to Haworth. Their deaths helped inspire the early chapters of Charlotte’s novel, Jane Eyre.

Haworth in the 1830s and 40s was a place where a lot of people died before their time. Mrs Brontë succumbed eighteen months after the family arrived. Emily died here, soon after Branwell, at the age of 29, never having realised what a success Wuthering Heights was becoming, and Charlotte died here too at the age of 39, having experienced success as a novelist and happiness as a wife. She was the only Brontë child to marry, and had she lived a few months longer, she would have given birth to her first baby. Anne alone of the writing triumvirate did not die in Haworth parsonage, but she would have if she’d been well enough to travel back from Scarborough where consumption did for her in 1849, also at the age of only 29.

Lest we think that the Brontës were an especially unfortunate family, it’s worth remembering that Haworth was a particularly toxic place in which to live. Today it seems a rural idyll but in the early decades of the nineteenth century, rapid industrialisation had made Haworth the most polluted place in England outside the slums of London’s East End. When the Brontë girls were growing up, the average life expectancy in Haworth was just 19.6 years. There were no drains in the village and human and animal effluent ran down the sides of Main Street. The village drinking water was polluted by rotting flesh from an overcrowded graveyard where Reverend Brontë worked overtime interring his parishioners.

All these grim statistics I read before visiting Haworth. Driving past signs for Brontë Country, Brontë Estate Agents and Brontë Autos, two thoughts gnawed at me: all that cramming in of people to fuel Yorkshire’s industrialisation meant that the Brontë girls did not live in the wild countryside described in Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre – and surely, tragic though their lives seem to us today, they enjoyed relatively long lives compared to most of their contemporaries in festering Haworth.

I parked at the top of a winding forested track. If you leave your car up here on Weaver’s Hill and pay your £4 for the day, you walk down a picturesque footpath to the church, past pastures and chicken-runs belonging to villagers.

Coming upon the grim dark tower of the church (a late nineteenth-century construction on the site of Patrick Brontë’s St Michael and All Angels) you can take a shortcut through to the parsonage or skirt the church entirely and end up in the village, which today is far cleaner than it was in the time of the Brontës. Here the apothecary’s shop where Branwell bought his opium and the pub where he drank himself to death both proclaim their unfortunate Brontë connection.

I walked up the hill to the famous parsonage, which is usually photographed to exclude the lofty Victorian extension that Mr Brontë’s successor, Reverend Wade, added in the 1870s. The rest of the building looks like a brighter, less gloomy and more loved version of the parsonage that we all know from the early ambrotype (a photographic print fixed on glass) from the 1850s.

Entering the parsonage, Mr Brontë’s study is on the right of the hall and the family dining room, where the three daughters would walk round the table discussing their writing, is on the left. A custodian told me it’s the original table which was sold off and bought back at great expense. A lot of money and research has gone into restoring the parsonage’s walls and carpets to their original vivid colours, and even if the curtains in the dining room are not the originals, they exactly match the description Charlotte gave when ordering them.

As the only surviving child – and a successful writer now with money of her own to spend – Charlotte had the dining room enlarged in the 1850s. She did the same with the bedroom above which became hers on marrying her father’s curate, Reverend Bell.

This enlargement of the marital bedroom was done at the expense of Emily’s former bedroom over the front door. Emily was now dead and obviously had no need of it, but reducing the room meant one wall had to be demolished, and the drawings on it by the Brontë children were lost.

The wall opposite is covered with very faint sketches that the four Brontës drew when this was what servants called the Children’s Study. This is the one room where the precocious siblings were undisturbed. Here the three Brontë girls acted out the plays they wrote, and dreamed up fantasy kingdoms – Angria, Gondal, Angora, Exina and Alcona – and wrote their miniature books. The drawings we can see today – heroes and heroines and attempts at self-portraits – are a direct connection with the world of the imagination that they created to escape from the unpleasantness of daily life in Haworth.

I stood entranced. So often these literary pilgrimages require an exercise of the imagination but this room is absolutely where it all began, a direct connection with the wellspring that produced three literary geniuses.

LINDETH HOWE, LAKE WINDERMERE, CUMBRIA – BEATRIX POTTER (1866–1943)

The Lake District had a huge impact on Helen Beatrix Potter, her writing and illustrations. Living in London as the eldest child of a wealthy lawyer, Beatrix was educated by governesses and grew up with few friends. The long summer holidays were spent with her family in Scotland until 1882, when they took a faux chateau on Windermere called Wray Castle. Thereafter the Potters rented for two or three months every year, settling in the end on Lindeth Howe as their holiday home of choice.

This large Victorian house had been built in 1879 and originally stood on its own in 28 acres of grounds with views over the lake. It was constructed of local slate and designed in that large-roofed, mock Tudor style that was fashionable at the end of the nineteenth century. By 1905, aged nearly 40, Beatrix was earning enough to buy her own Lake District home at Hill Top, Sawrey, on the other side of Windermere, but she was still required to spend time with her parents in Lindeth Howe, right up until her father’s death in 1914.

We know from letters which she sent to her publishers, Frederick Warne & Company, that the first images of Pigling Bland, Kitty-in-Boots and the squirrel Timmy Tiptoes were sketched at Lindeth Howe. In 1911 Beatrix wrote from Lindeth that she had compressed the words in Timmy Tiptoes to fit the page, ‘but it seems unavoidable to have a good deal of nuts’.

Beatrix’s first book was published by Warne in 1902. Later the runaway success of her work meant that she was also able to buy Castle Cottage, near Hill Top, where in 1913 she moved to live with her new husband, a shy local solicitor called William Heelis.

Today it seems extraordinary that a successful writer in her 40s was expected to return to London with her family at the end of every Lake District summer holiday. And that during those vacations she was also required to commute across Lake Windermere from Hill Top or Castle Cottage whenever her parents wanted her. Not entirely approving of Beatrix’s retreat at Sawrey, the family rarely sent a car to meet her off the ferry. She may have had a room of her own on one side of the lake, but she was expected to spend a lot of time on the other.

In July 1914 Beatrix wrote to Warne from Lindeth Howe, clearly frazzled about the delay in finishing Kitty-in-Boots: ‘We have been here three weeks already and it means nothing but going backwards and forwards. I have tried to get on with the book.’

That year Beatrix’s father died. The following year Lindeth Howe came on the market and Beatrix, now a wealthy woman, bought it so her mother could remain in the Lake District nearby – but not too near. By this time Beatrix and her husband were enthusiastically breeding sheep at Castle Cottage and she’d almost stopped writing and illustrating.

Mrs Heelis, as Beatrix now styled herself, was an astute farmer but also concerned by the government’s plans after the First World War to turn the Lake District into one huge conifer plantation. Her eyesight might have no longer been up to those perfectly crafted illustrations, but she had a clear vision of what she wanted to do next: buy up land to thwart the government. By the time of her death in 1941 she was able to bequeath the National Trust 4,000 acres of land, sixteen farms, plus numerous cottages and herds of cattle and sheep. Her gift made it possible for fell farming to continue in the Lake District rather than be driven out by forestry.

I had previously visited Hill Top, like so much of Beatrix’s land now a National Trust property, but finding that Lindeth Howe was now a hotel, I decided to stay in the parental holiday home. Here in 2009 a ‘Potter Room’ was created out of the large south-west bedroom where Helen Potter, Beatrix’s mother, slept in her widowhood.

The house lies up a hill from the Windermere ferry. It looks very like the photos taken by Beatrix’s father – a keen amateur artist in his own right – but it has subtly doubled in size since his day and ten new houses have been built in the grounds, each one reducing the wide open space around the original. As the trees have grown up, the Lakeland view has all but disappeared too. Only when the trees lose their leaves in winter do you see Windermere from the lawns these days.

Inside, Lindeth Howe has the feel of a house that is moonlighting as a hotel. There is no reception and in the drawing room there are photos of Beatrix visiting Lindeth as an older woman. While I sat there waiting for my room to be ready, I watched a short film drama that the hotel has recently produced, showing Beatrix travelling from Hill Top to Lindeth Howe on foot, ferry and family car. The author is played by a local actress who specialises in reading her work. I was beginning to realise that this part of the world really values her, not so much as a famous writer but as a cherished local. This impression was further enforced by a trip I took later that day with Mountain Goat tours, which visited all the Beatrix sights including Hill Top and Wray Castle. My guide, a retired local police officer, was eloquent about Potter’s work preserving the Lake District. That afternoon we saw various landscapes that found their way into the illustrations for Beatrix’s books – there are no generic lanes or fences in her work – and it was nice to think that she returned the compliment, protecting the landscape that so inspired her.

At the end of the day I sat in the window of the ‘Potter Room’ at Lindeth Howe reading The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes while Japanese tourists took turns photographing each other on the garden’s wooden swing seat below. Comfortable as the room was, I felt no particular connection with Beatrix or her forbidding mother in it, but the view, remarkably unspoiled by the hundred years since Beatrix bought this house, did feel like her view. I think that’s the kind of memorial she would have wanted.

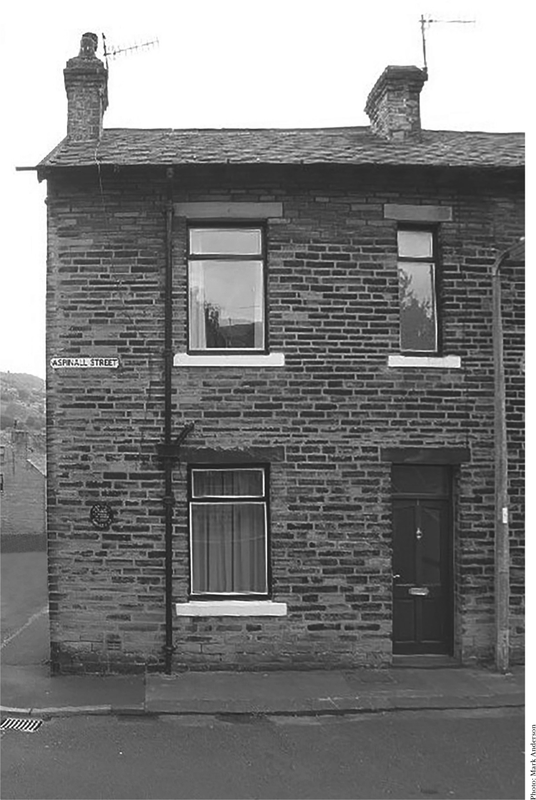

ASPINALL PLACE, MYTHOLMROYD, WEST YORKSHIRE – TED HUGHES (1930–98)

Given that being born is usually the least of a writer’s achievements, I tend to avoid visiting birthplaces of famous authors but when The Independent invited me to be the first guest to stay in Ted Hughes’ family home a few years ago, it was too tempting to resist. The birthplace of our former Poet Laureate in Mytholmroyd had just been opened as a holiday cottage. My mind boggled. Hughes was a writer of towering stature but his world – all black crows, rain and darkness – was not one you’d immediately think of vacationing in.

My drive was across Yorkshire moorland to the old cotton town of Mytholmroyd (pronounced MY-thom-roid) which nestles in a narrow industrial valley. I actually overshot and had to reverse by a genuine clog factory before finding somewhere to park in Aspinall Place.

What lay behind the lilac half-glazed door of No. 1? Would this be a painstaking recreation of the kind of house lived in by a joiner, his wife and three children in the 1930s? I really didn’t fancy pulling up a tin bath in front of the fire that evening. What I found was very like a National Trust holiday cottage. A leather sofa and armchair sat on a neutral Berber twist carpet, facing a flame-effect fireplace that was more 1930s Mayfair than Calderdale clog factory.

Only the leafed dining table and chairs were recognisably of the period. A few sepia photos were dotted around, including one on the mantel of Ted in 1938 wearing a V-neck school sweater, possibly the last time he ever smiled for a camera.

The whole place nodded in the direction of the interwar period without creating a museum. It’s a holiday cottage which would like to be used by writers and, if you want it, the Birthplace Trust curator is happy to talk about Hughes. There is no shortage of local people nearby who will tell you about Ted (or even ‘Teddy’ as I heard him called).

There was a new kitchen and, to my relief, the bedroom of Ted’s sister Olwen at the top of the steep stairs is now a modern bathroom. So no tin bath in front of a coal fire. The main bedroom where Ted was born contains a Victorian brass reproduction bed. There was also one of those awful veneered 1930s dressing tables with tall bevelled mirrors like the one that my mother inherited from her own mother. As a child I loved to angle the three mirrors carefully to create a triptych of reflections.

This conversion had probably got the tone about right, given the nearly impossible brief to refurbish an uninspiring terraced house as a desirable holiday-cottage-cum-shrine-cum-writers’-retreat. Downstairs I cleared some of the family photos off the parlour table and powered up my laptop. Sylvia Plath, who stayed here with Ted en route to Haworth, once recorded: ‘I wonder if, shut in a room, I could write for a year.’ All I had to do, relieved of the pressures of domestic life and friends, was to write, like her, one day at a time. It was odd to think of Sylvia and Ted off on their Brontë pilgrimage. With Haworth only ten miles away, this remote, post-industrial landscape has the most improbably grand literary connections.

That evening I’d been invited to dine with members of the Elmet Trust, who strive to keep the local connection with Ted Hughes going through ventures like 1 Aspinall Place. They’d chosen the name Elmet because, in his later years, Ted insisted that Calderdale was part of Elmet, the last Celtic kingdom in England. I walked with the secretary of the Trust down to the church hall where dinner was being held. As we passed over the Rochdale Canal, she pointed out where young Teddy and his friends used to throw stones to smash the windows of an empty factory, an act he later commemorated in the poem ‘Under the World’s Wild Rims’.

The dinner was a jolly occasion although our speaker made the point that Ted would never have given an after-dinner speech. He would have seen it as a frivolous waste of literary energy. While more than one member of the Trust attributed Ted’s distinctive literary voice to ‘Pennine gloom’, they spoke of him with great fondness. For his part, the poet kept his connection with this industrial scar in the Yorkshire moors, returning often.

After an uneventful night in the room where Ted was born, I wandered round the village in morning drizzle. I got as far as Sutcliffe Farrar, a company that still produces men’s trousers in Mytholmroyd. Ted’s mother, Edith Farrar, was a seamstress and a relation of the owner. Evidently the modern en-suite shower off my bedroom used to be her workroom. As there was no Wi-fi in Ted’s birthplace I looked for the Dusty Miller pub where the connection was said to be good, but it wasn’t lunchtime yet and its doors were bolted. By now it was raining heavily so I picked up a takeaway lunch from the tiny local Sainsbury’s and marched back against the brewing storm. Rain was overflowing the gutters and a lorry sent a spray of grey water over me and my little orange bag of groceries.

That afternoon, however, the weather improved and I hiked up to The Heights, a road that runs atop the surrounding hills, with one of Ted’s schoolfriends. Ever since his retirement from Sutcliffe Farrar, he’d devoted himself to tracking down local references in Ted Hughes’ complete oeuvre. ‘There are 27 poems set in Mytholmroyd alone,’ he explained as we walked up along Zion Place, ‘all of them on this side of the river.’ I looked at his maps that showed where the Hughes brothers used to camp, where Ted shot his first rat in a pig oile (pigsty) and where the Bessie House (a sweet shop) once stood.

The sun came out at last and I began to understand why this landscape inspired so much of Hughes’ writing. As we descended from The Heights, my host pointed to a kestrel that had paused in flight, feathers fluttering above the landscape. ‘That’s Ted, watching over us,’ he said. ‘I hoped he’d be here.’

PORTMEIRION, GWYNEDD, NORTH WALES – NOËL COWARD (1899–1973)

There can be very few literary travels as successful as the train journey that Noël Coward took to North Wales in May 1941. Coward had just returned from the United States and was sure that he could help the British war effort by giving people something to laugh at. ‘A light comedy had been rattling at the door of my mind,’ he later claimed. In the company of his long-term friend and collaborator, actress Joyce Carey, Coward left London, which was still enduring its nightly Blitz at the hands of the Luftwaffe, and travelled north-west to Portmeirion.

The architectural fantasy village of Portmeirion had been begun in 1925 by a Welsh architect called Clough Williams-Ellis. He dubbed it, among other things, ‘a home for fallen buildings’. Sir Clough did not like the modernism, functionalism and brutalism of contemporary architecture and had begun salvaging bits of old buildings he came across. He had also bought a valley along the Dwyryd estuary which he named Portmeirion. Here he reassembled them. A friend of Clough’s, the sculptor Jonah Jones, described the village before the Second World War as ‘a delightful hotchpotch of sometimes disparate structures, Bavarian vernacular, Cornish weather-board, Jacobean, Regency, Strawberry Hill Gothic …’

At its centre, and nearest the estuary, stood an old hotel that Clough had restored, although from very early on guests were encouraged to stay in the eccentric cottages that he was creating on the estate. From the beginning of their joint enterprise Amabel, Clough’s wife, had invited writers and artists to come to their new ‘village’. One building, ‘The Chantry’, was built in 1937 specifically so that Augustus John might use it as a studio, but sadly the free-spirited painter never turned up.

By the time Noël Coward took up Amabel’s invitation in 1941, work had temporarily ceased on the resort, but the main buildings that can be seen today were in place. He and Joyce Carey took a suite each in a building called ‘The Fountain’. Joyce described Portmeirion as ‘the perfect place, a small “mother” hotel and houses built in varying sizes and designs within reach of it’. They had brought with them their typewriters plus paper and carbons and, according to Coward, ‘bathing suits, sun-tan oil and bezique cards’. On the first morning, 3 May 1941, as Australian troops launched an ill-fated counter-attack on the Libyan port of Tobruk, the writers sat out on the beach with their backs against the sea wall. Coward described his play, coming up with names for the characters as Joyce Carey asked the occasional question. By the end of the day Coward was sure he was ready to start writing the next morning and he announced their daily schedule. Breakfast at the hotel would be followed by work from 8am till 1pm. Then there would be a break for lunch (without alcohol) followed by more writing from 2pm until 5.30 or 6pm when they would meet up and Coward would read his day’s work out aloud to Joyce. ‘Then bath, a drink, dinner and bed about eleven,’ she recorded.

Joyce was working on a play about Keats, ‘Wrestling with Fanny Brawne’ as Coward dubbed it, but his work was the undoubted priority. ‘In five days Blithe Spirit was born,’ he recorded. The play opened that year and ran very successfully in London and on Broadway. A UK touring production was put together for morale-boosting purposes with Coward in the role of Charles Condomine and Joyce as his second wife Ruth.

I have been visiting Portmeirion since I was a child. In 1967 my parents took me there just after the first season of the TV series The Prisoner had finished filming. Also there at the time was Clough’s grandson, Robin Llywelyn, only eight years old but already introduced to the writer and star of that series, Patrick McGoohan. I would have been so jealous had I known. Robin and I didn’t meet then, but we have many times since. He has become a highly successful writer in the Welsh language while at the same time managing director of Portmeirion Ltd, which still runs his grandfather’s village as a resort.

I’ve stayed in several of the cottages – my favourite is White Horses, which is directly on the sea wall and where Patrick McGoohan lived while writing, directing and starring in The Prisoner. But although my wife and I have walked past Anchor and Fountain, as Noël Coward’s block is now known, I was unaware until recently that this was where Blithe Spirit was written. It’s a tall building, resembling a gaunt, early nineteenth-century pub on the outside but wholly modern within. There is no plaque on the wall, just as there is no plaque to any of the other illustrious visitors who have stayed and written at Portmeirion – apart from Patrick McGoohan whose presence is recorded on the wall of White Horses. Although it attracts its fair share of celebrities, literary and otherwise, Portmeirion is still all about the village that Sir Clough created.

Since Clough Williams-Ellis’ death in 1978 the world has moved a lot closer to his view of architecture, which pleases me greatly. Buildings are not just machines for living in. We need beauty. We need whimsy.

As for Noël Coward and Joyce Carey, he lived long enough to fall out of and back into fashion, while she is probably most immediately recognised today as Myrtle who runs the station café in Brief Encounter, Coward’s bittersweet love-story so wonderfully filmed by David Lean in 1945. Joyce lived to the age of 94 and remained a close member of Coward’s adopted family. Whatever happened to her play about Keats I have no idea, but Noël Coward’s week at Portmeirion was highly productive. Clough’s village certainly wove some magic because Blithe Spirit is still played all round the world today.