CHRIST CHURCH – LEWIS CARROLL (1832–98)

Oxford, a very real city, one hour up the M40 from London, has inspired an extraordinary number of fantasy writers. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) wrote about Alice Liddell’s adventures down a rabbit hole and through a looking glass in Oxford. Clive Staples Lewis (aka C.S. Lewis) invented Narnia here, and John (J.R.R.) Tolkien created Middle Earth. More recently Philip Pullman found a parallel universe between the hornbeams on Oxford’s Sunderland Avenue in his Dark Materials trilogy. Only Colin Dexter with his Inspector Morse crime novels has reflected the everyday reality of Oxford, a city of sexual intrigue, gluttony and murder.

Being based in Oxford for the last fifteen years, I’m aware of the paradox that most of the authors who live here could write about this fascinating city but instead prefer to disappear down their own rabbit holes. It seems to be the mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson who started this trend with Alice’s Adventures Underground, which he changed to Alice in Wonderland when the story was published in 1865 under his pen name, Lewis Carroll.

Carroll lived and worked at Christ Church, one of the largest of Oxford’s colleges. It sits on St Aldate’s, a street that runs down towards the Thames. The college was built by Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII’s chief minister at the time when he was trying to arrange the king’s divorce from his first queen, Catherine. Initially known as Cardinal College, it was renamed King Henry VIII’s College after 1529 when Wolsey fell disastrously from favour. Finally in 1546 it was refounded by Henry as Christ Church.

When I was a student, Christ Church was renowned, even among those of us not studying at Oxford, as the ‘heartiest’ of English colleges. Allegedly, while most Oxford colleges raided a rival, throwing their beds out of windows as a prank, the wealthy students of Christ Church were so thick that they simply threw their own beds out of the windows. Perhaps in Dodgson’s day undergraduates were not quite so silly – after all, Christ Church has produced more British prime ministers than any other college in Oxford or Cambridge.

It was a bright May morning when I paid my entrance fee. All Oxford colleges admit visitors on selected days but after the success of the first Harry Potter films – in which Christ Church’s Great Hall doubled as Hogwarts – this was one of the first to charge admission.

The bowler-hatted ‘bulldog’ (custodian) who showed me round was tired of people hoping to find Snape and Dumbledore at Christ Church and was positively happy (bulldogs rarely smile) that I’d come here in search of Carroll. He pointed up to one of the windows of the Great Hall that is dedicated to the author and which contains a portrait of Alice Liddell.

Alice was one of the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, and at the age of four she captured the attention of the middle-aged don Carroll, who was a keen photographer. A picture of her at the age of seven by Carroll shows a child with an unusual amount going on behind her eyes. A later portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron of Alice as a young woman suggests restless discontent.

Also in the Great Hall I was shown the fire grate supported by two human figures with elongated necks. They are said to be the inspiration for Alice’s potion-induced long neck in Wonderland. Behind High Table I saw a panelled door concealing a narrow spiral staircase by which academics could suddenly disappear, like rabbits, downstairs.

When I asked if it were possible to see Lewis Carroll’s actual rooms, the bulldog shook his head and just nodded towards the north-west corner of Tom Quad. This is a working college still and those rooms, overlooking St Aldate’s, are always occupied by an academic, who probably does not see their role as part of the tourist trail. Instead, I was shown Dean Liddell’s gardens where there is a voluminous chestnut tree. Evidently Alice’s real cat Dinah used to seat herself in it in a most Cheshire Cat-like way. From here there is a door into the beautiful Cathedral Garden, which was always kept locked because little girls were not allowed to play in there. Alice however could see into it from the nursery, something else that might have inspired Lewis Carroll’s inaccessible garden in Wonderland.

On my way out I called into the small shop at No. 83 St Aldate’s, which is now known as Alice’s Shop. This name is not only derived from its shelves of Wonderland merchandise. Here behind a red wooden door was the sweet shop where Alice Liddell would buy her barley sugars. The shopkeeper at the time, an old lady wrapped in a shawl, apparently reminded Alice of a sheep and she confided this, like so much else, to Carroll. The sheep-shopkeeper crops up in one of the more surreal sections of Through the Looking Glass.

The more you know about Lewis Carroll’s Oxford the more you realise his Alice stories are an eccentric tapestry woven out of the threads of her life – and his own. Carroll put himself and his friend Duckworth into Wonderland as the Duck and the Dodo (a pun on the stuttering Do-Do-Dodgson’s name). At the Museum of Natural History on Parks Road you can even see one of the few stuffed dodos in Europe, a bird that Alice and Carroll would have visited.

Ultimately, however, these sources of inspiration fail to decode Alice’s adventures. The books themselves defy explanation, but it can be great fun spotting the raw material that was reworked in Lewis Carroll’s remarkable imagination for his favourite audience. I didn’t see his college rooms but I definitely saw the city that inspired him.

THE EAGLE AND CHILD – J.R.R. TOLKIEN (1892–1973)

Many years ago I took my friend Jeremy for a drink in Oxford on the eve of his wedding. I was to be his best man the next day and felt I should offer some kind of stag night. We met up at the Eagle and Child, a narrow inn on St Giles dating back to at least the English Civil War, and I bought us both pints. We sat in one of the tiny front parlours where on a busy day you rub knees with the other drinkers, so close are the tables. After we had finished our beers my old school friend announced that he had to leave for dinner with his parents. That was the end of what became known thereafter as Jeremy’s Stag Half-Hour.

Coming back to the Eagle and Child many years later on J.R.R. Tolkien’s birthday, I noticed few changes. It’s one of those English pubs where alteration, let alone refurbishment, is anathema. The most obvious innovation was a large painted portrait of the Lord of the Rings author over the small Victorian fireplace in the parlour where we’d sat in the early 1990s. There was a matching portrait of C.S. Lewis in the equally small parlour on the other side of the pub’s narrow vestibule. Tolkien and ‘Jack’ Lewis, good friends and colleagues in real life, fellow creators of fantasy worlds, are a partnership in Oxford tourism today. At Magdalen College you can stroll along Addison’s Walk, a triangular route named after an eighteenth-century college Fellow, which they took together when Lewis was grappling with converting back from atheism to Christianity.

The Eastgate Hotel, lying between Lewis at Magdalen and Tolkien at Merton College, is one of many drinking places that hosted the writers, usually for a Monday morning pint.

But the Eagle and Child (also known locally as the ‘Bird and Baby’), was where Tolkien and Lewis would meet their fellow ‘Inklings’ on Tuesdays in a back room behind the bar. They met in the Rabbit Room where they would read and discuss each other’s work. Tolkien, a purist whose Middle Earth was essentially Anglo-Saxon, would despair of Lewis’ habit of yoking in characters from every era and world culture for his Narnia novels.

So recently on a wet Tuesday in January at noon I made my way to the Rabbit Room of the Bird and Baby, and ordered a half-pint of real ale in memory of my own Oxford friend. A new sign by the bar quoted from Pippin and Merry in the first film in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy:

What’s that?

This, my friend, is a pint.

It comes in pints? I’m getting one.

I, however, was here only to catch some hint of Tolkien, not to get as drunk as a hobbit. While waiting for my half to pour, I occupied myself looking round the Rabbit Room. The partitioning has been removed since the 1940s, making it more of a corner of the bar now. Black and white photos of Tolkien and Lewis are framed on the walls, along with images of Oxford in their time. There are two long tables, a fireplace, a commemorative plaque and a few books. On a wet day like today it was easy to imagine a group of middle-aged Oxford dons squeezing in together, their tweed jackets steaming slightly as they dried off in front of the coal fire.

It’s less easy to imagine Tolkien finding anything of the grandeur of Middle Earth in the Eagle and Child, although he did write scenes in the Prancing Pony, the Green Dragon and the Golden Perch, which definitely have something of the dark, clutter and noise of these small wood-panelled rooms.

A half of warm British beer lasts no time at all, so in a break between downpours I got back on my bike and wondered where to head next in pursuit of J.R.R. The Inklings also met across the road at the Lamb and Flag. Lewis and Tolkien seemed to convene anywhere a pint could be poured but instead I headed into the centre of Oxford and its medieval colleges.

I could have visited Merton, where Tolkien was Professor of English Language and Literature for twelve years until his retirement and move to genteel Bournemouth, but Magdalen College lets you in for free if you’re a local. It also has a medieval tower overlooking the River Cherwell and a gift shop selling C.S. Lewis memorabilia which I enjoyed browsing.

This was the home of Tolkien’s literary comrade – even though the relationship cooled in the 1950s after Lewis married without telling any of his friends. The college grounds are extensive, like those of a British stately home, and extend to an island in the River Cherwell on which runs Addison’s Walk. It’s lined with so many trees that in summer it can resemble a dark tunnel. The Tolkien Society claims that Addison’s Walk may have inspired his depiction of Mirkwood. Certainly the stumps of dead trees that have been carved into chairs have a Middle Earth quality about them.

I completed a circuit – if indeed triangles have circuits – and then the rains blew back in again. I stood under a leafless tree and wondered like Bilbo, sheltering in the goblin cave, why I had ever left my warm hobbit-home. I could cycle to 20 Northmoor Road now, Tolkien’s house where, while marking examination papers, he wrote down the words: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ Or I could cycle as far as the Wolvercote Cemetery and Tolkien’s grave. Both were suitable acts of pilgrimage, but the house is in private hands and the grave was over three miles of rain away. So in the end I went back to the Bird and Baby and ordered a pint this time and drank another toast to Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis, and to my friend Jeremy who had died – ridiculously young – the previous autumn.

KELMSCOTT MANOR, OXFORDSHIRE – WILLIAM MORRIS (1834–96)

There can be few writer residences as satisfying as Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, where William Morris lived from 1871 until his death. Yet it is one almost wholly without revelations. We want a bit of a surprise when we visit a writer’s room, I think. We want to learn something unexpected.

Morris, a man of remarkable energies, threw himself into his life, working as an artist, designer, poet, novelist, translator and printer. While Thomas Hardy and Gerard Manley Hopkins – his almost exact contemporaries – took the novel and poetry towards Modernism, Morris took Britain back to the misty Middle Ages.

Kelmscott Manor, built in 1570, looks like a setting for one of Morris’ books. The polymath did most of his writing here, having given up painting by 1862. Among books written at Kelmscott were The Story of Sigurd the Volsung (1877), Hopes and Fears for Art (1882), A Tale of the House of the Wolfings (1889), Poems by the Way (1891), News from Nowhere (1890) and The Wood Beyond the World (1894). He also wrote a number of translations – The Odyssey, The Aeneid, Beowulf and Old French Romances. His work was widely read. These days, when the words ‘William Morris’ are almost always followed by ‘design’, ‘style’ or ‘wallpaper’, it is salutary to realise that in his lifetime Morris was better known as a writer.

William Morris’ pursuit of a purer world that looked medieval but practised socialism was helped by his being born into a wealthy family. He could afford to follow his dreams and live where he wanted. Morris was accompanied on these adventures by his wife Jane, whose beauty he fell for while a student at Oxford, and by the poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who spent most of his adult life in love with Jane and was incapable of painting any subject well apart from her. Jane Morris became the face of Pre-Raphaelite beauty. Her large dark eyes, long nose, full lips and resolute chin can be seen everywhere in Victorian art, in book illustrations, in paintings, even in stained glass. The ideal – for both men and women – was to look like Jane Morris. Thanks to the adoration she inspired in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, there are even graphics accompanying newspaper reports of the Boer War in South Africa in which the heroic young subalterns all look like Jane.

Theirs was a strange ménage. By the time the three of them arrived at Kelmscott Manor, Morris had already built the innovatory neo-Gothic Red House in Kent and moved from there to Queen Square in Bloomsbury, where his design business, Morris & Co., prospered. He then decided he wanted to bring his children up in the country. Kelmscott, a limestone Elizabethan manor house, was perfect and he took a joint tenancy with Rossetti.

Arriving at Kelmscott the day the RAF were doing a series of public displays at nearby Brize Norton, I couldn’t miss the dramatic contrast between the Red Arrows overhead and the pink roses over William Morris’ door, disturbing his medieval idyll. The house is owned by the Society of Antiquaries and it’s opened only on Wednesdays and Saturdays. After Morris’ death Jane Morris bought Kelmscott and offered to leave it to Oxford University if they would preserve it as a museum. The university declined so it went to the Antiquaries.

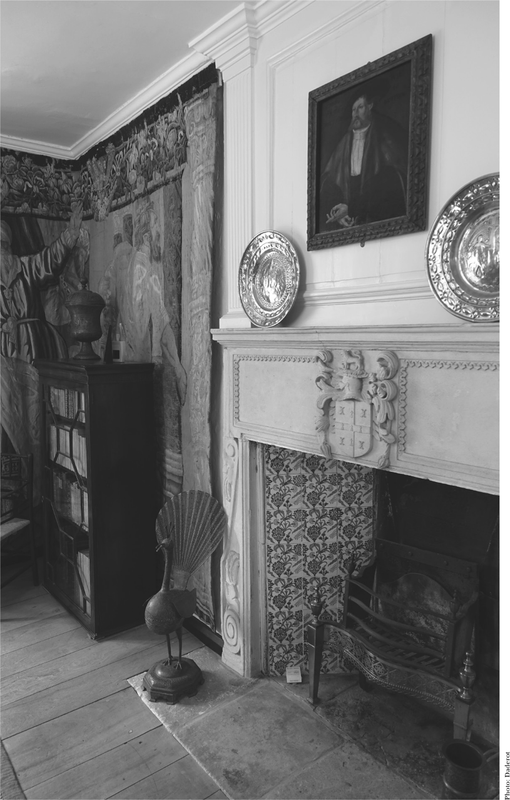

Inside the manor house were pictures and decorative works by Morris, Burne-Jones and Rossetti as well as Philip Webb (architect of the Red House). The whole building looked like a showcase for William Morris design in its furniture, textiles, paintings, carpets and ceramics. The walls were covered with Morris’ take on medieval tapestries, and the four-poster beds were draped with them too. His trellis wallpaper and oakleaf motif fabrics were everywhere. Looking at the fireplaces and casements that had not been modified by Morris, I got the feeling that when he moved in, the house might have resembled a nineteenth-century vicarage out of George Eliot but the Morrises took it back to Chaucer’s time.

It was all very pretty and full of people recognising the originals of their cushion covers or curtains, but it was just what I expected. The only surprising element was in the outhouses where my wife and I found a converted farm building containing a triple lavatory where three people could sit simultaneously. With or without plumbing (I did not check).

Of all of Morris’ design innovations this was the most unlikely. It was difficult to imagine it being used by this middle-class Victorian household so I found it particularly delightful to come across a caricature that Osbert Lancaster had penned of Rossetti, Jane and Morris sitting on the lavatories, the men with their trousers round their ankles and Morris furrowing his brow as he tries to read La Roumant de la Rose in the original French.

William Morris has become one of those great unread writers now, like Charles Kingsley and Vita Sackville-West. He achieved a remarkable amount in his 62 years. In addition to his writings and design business, he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings to guard against the philistinism that accompanied Victorian notions of progress. He founded the Socialist League to work for greater social justice, and the Kelmscott Press to publish beautifully-illustrated limited-edition books. And of course he gave us the ‘William Morris’ look, which still sells around the world.

Before we left I bought a William Morris mug lettered with one of his best known declarations. ‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.’ Prescient words at a time of Victorian clutter and worth remembering today. But tellingly I did not buy a copy of Hopes and Fears for Art in which Morris made that statement.

I hoped he’d forgive me.