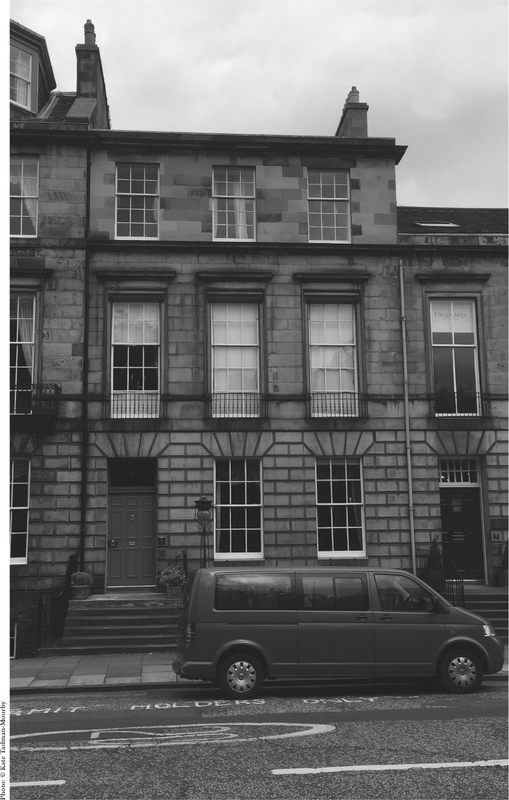

HERIOT ROW – ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON (1850–94)

There’s no mistaking the house where the author of Treasure Island grew up in Edinburgh’s neoclassical New Town. Chiselled into the sandstone are the words ‘The home of Robert Louis Stevenson 1857–1880’ and next to the large red door an old brass plate reminds you that this is a private house, ‘Not A Museum’.

Fortunately 17 Heriot Row is also a B&B run by a bearded gentleman and his wife who glory – can there be any other verb for it? – in the names of John and Felicitas Macfie. Mr Macfie is the eleventh owner of this triple-bayed, terraced house built in 1808. The sixth owner was Thomas Stevenson, father of Robert Louis. The Stevenson family arrived here in 1857 when their only child Robert was six years old. It was hoped that this south-facing house on higher ground would be better for Stevenson’s young wife and son, both of whom were prone to chest infections.

A devoted father, Mr Stevenson had the roof level of the house raised so that his only child would have two spacious, sunny rooms on the second floor, one as the day nursery and the other as the night nursery. There would also be a comfortable room for Robert’s nanny at the rear of the house. This is now one of the rooms that Mr Macfie lets out to paying guests with two single beds and an en-suite shower.

Down below, the room where Robert’s parents slept is also available to guests. It has an en-suite bath that was installed after young Robert married in 1880 because his American wife thought it antiquated to carry pails of hot water through the house. According to Mr Macfie, the redoubtable Fanny Matilda Van de Grift Osbourne Stevenson teased her father-in-law about his parsimony for not installing a modern bathroom – and the tactic worked. Thomas Stevenson, a successful designer of lighthouses, not only installed a panelled-in bath that guests use to this day but a cold water shower over it (also still working).

Mr Macfie told me all this as we sat drinking tea in the massive red dining room at the front of Stevenson House. When he and his wife redecorated No. 17, they stripped off ten layers of paint and discovered that the wood panelling of the house would have been brightly coloured in the mid-nineteenth century. Some walls were even painted a dazzling yellow. Sepia photography does not do justice to how garishly the Victorians decorated. They had access to aniline dyes – fuchsia, Magdala red, Tyrian purple, Martius yellow, bleu de Paris and aldehyde green – that simply could not be mixed in Jane Austen’s pastel time.

After drinking our tea we went upstairs to see Mrs Stevenson’s drawing room overlooking Heriot Row. The hall and stairs are lit from an oval skylight in the roof and are wonderfully spacious, but then they were public areas for visitors to traverse, far more so than today when we invariably receive visitors on the ground floor.

At the top of a flight of stairs lined with swords, a large wooden door opens into the drawing room which runs the width of the house. Here the sixteen-year-old Robert, listening to his mother and her friends decry the behaviour of young people today, interjected from the shadows, ‘I’m not as black as I’m painted’. One of them returned home to declare she had just met a young poet, a Heinrich Heine with a Scottish accent who ‘talked as Charles Lamb wrote’.

We then went to the topmost floor to see the bedroom of Alison Cunningham (known as Cummy), the nanny to whom Robert dictated his childhood stories. Up here was Stevenson’s own bedroom and the day nursery where as a teenager he wrote some of his earliest works, including The Pentland Rising, which was privately published by his father when he was sixteen.

Later, after Robert Louis Stevenson had fallen out with his parents and married Fanny, a divorcée, against their will, he returned to this house with his new wife and she helped effect a reconciliation between parents and beloved son. The newly-married Mr and Mrs Robert L. Stevenson would have stayed in his old rooms at the front of the house and Mr Macfie is sure that parts of Treasure Island were written in the old day nursery. So I was excited to see where one of the most gripping books of my childhood had been created.

However, when the door swung open what I saw was the bedroom of Mr Macfie’s twin daughters, looking as such rooms often do. My host tried to explain where the book shelves would have been and how Robert Louis Stevenson had trunks full of more books stacked against the windows, but I just couldn’t see past the clutter of contemporary childhood.

Later in Edinburgh’s Writers’ Museum I saw Stevenson’s riding boots, the shell and silver ring given to him by a grateful Samoan chief at the end of Stevenson’s travelling life, and a wardrobe made by Deacon Brodie (the inspiration for Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde) that used to stand in the nursery and which may have inspired the young writer. But I couldn’t help thinking of that room full of mattresses, Playmobil and cuddly toys.

THE ELEPHANT HOUSE – J.K. ROWLING (B. 1965)

Tables in Edinburgh where J.K. Rowling sat and wrote Harry Potter are becoming as ubiquitous as beds in which Queen Elizabeth I slept and bars in which Hemingway drank. The author has gone on the record about two Edinburgh locations, however. One of the best-selling novelists of her generation began the Harry Potter series in The Elephant House café on George IV Bridge and ended it at the Balmoral Hotel.

The Elephant House is in one of those big, dark Edinburgh buildings that seem to extend over an infinite number of floors above and below street level. A large faded sign on its exterior wall reads Harvey’s Furniture Show Rooms. In 1995 a café opened here with a large carved elephant chair, a cabinet of miniature elephants and elephants stencilled round the mirrors. It was inside this that the newly divorced, unpublished author would bring her daughter in a pram. The myth that J.K. Rowling wrote in cafés to avoid heating her flat has been quashed by the author. She used the pram ride to lull her child to sleep. Then she could park the two of them at the back of this bright bohemian café and write overlooking Greyfriars churchyard.

Visiting The Elephant House today it’s clear that the café is proud of its unique identity, with Elephant T-shirts for sale at the end of the long counter, but a few cuttings on the notice boards reinforce the Rowling connection, and there is a sign in the window that reads ‘The Elephant House, “Birthplace” of Harry Potter’. The same claim is made in Mandarin underneath. Chinese tourists love to stand outside and block up the wide pavement as they take selfies and groupies.

The café is rarely quiet. The noise of the coffee grinder, the hubbub of voices and the sound of traffic every time the door swings open blend into a wall of noise within which it is surprisingly easy to concentrate. I write in cafés myself. In this one you get your coffee and pastries at a counter and are then supposed to wait to be seated, but every time I’ve visited, the staff have been too busy behind the counter. So it’s easy enough to walk through to the back room and aim for the table with the metal ‘reserved’ sign which is where, as she recorded in a TV programme, J.K. sat whenever she could. There’s no plaque on the wall, however, nor anything as obvious as the large arrow hanging from the ceiling in Katz’s Deli in New York pointing to where Harry and Sally discussed female orgasms. The only permanent form of commemoration for one of the most successful book series of the late twentieth century is in the small lavatories nearby. They are covered in graffiti: ‘Harry, yer a wizard’, ‘Dobby is a Free Elf’ and ‘“Let me Slytherin,” said Draco Malfoy to Hermione’. The owners have long ago given up painting over the scrawls that cover the walls, mirrors and windows.

On my way out I noticed a signed first edition of the first Harry Potter novel inside the glass case containing elephants. But on the whole, the Rowling connection is low-key. Who knows what other novels are being written there now?

On the other side of the massive North Bridge, opened in 1897 to link Edinburgh’s Old and New Towns, stands the Balmoral Hotel, originally the North British Station Hotel, a massive fortress of a Victorian hotel built to service the Waverley Station below. Here in Room 552, now the J.K. Rowling Suite, is where the last of those Harry Potter novels was completed, behind a door which in her honour now has an owl door knocker – unlike the other 187 hotel rooms.

Inside is a living room and bedroom in light blue with views up to Calton Hill and a Jack Vettriano print over the bed. There’s also a marble bust of Hermes on which the author recorded, ‘Finished writing Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in this room (552) on 11 January 2007’. I doubt that most guests have their graffiti preserved in this way. The desk at which the author sat has been preserved in situ, but there’s not much else of Potter or Rowling apart from the complete novels with their multi-coloured spines on a small shelf below some baronial-looking antlers. The room is fully booked for the foreseeable future. I was only able to see it in the brief window after housekeeping had been in and just before the next literary pilgrims arrived.

On my way out of the Balmoral I called in at the lovely Palm Court lounge where afternoon tea is taken these days as a harpist plays amid the tall white Corinthian columns. ‘J.K. Rowling used to write here,’ said the woman who showed me to my table, ‘usually at that table facing the mirrors. She liked how old they were’ (they are indeed) ‘and she preferred to face them because it was less distracting than facing into the room.’

Truly J.K. Rowling did write everywhere.