THE BUCKINGHAM HOTEL, NEW YORK – DAMON RUNYON (1880–1946)

Damon Runyon is one of those writers so deeply associated with the city in which he wrote that he bequeathed New York an adjective: Runyonesque.

It helped that he lived the life he wrote about. Runyon was the archetype of the tough, hard-nosed street reporter who fraternised with gangsters, bookmakers and sportsmen. Al Capone was a friend, so was the boxer Jack Dempsey and the baseball player Babe Ruth.

He smoked and drank coffee continuously and when he wasn’t in his apartment, he was usually making notes in Lindy’s Deli – when he wasn’t at the Stork Club. Runyon was hardly ever home, leading his first wife, Ellen, to claim that if he died and she went to his funeral she doubted she would recognise any of the other mourners.

Damon Runyon chronicled New York in the 1920s, 30s and early 40s through his journalism and short stories. In tales like The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown, Blood Pressure and Pick the Winner, his New Yorkers spoke in an idiosyncratic mix of formality and slang that can still be found widely emulated from the gunmen in Kiss Me Kate, to Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway, and even The Sopranos. They went by the most marvellous names: Nicely-Nicely Johnson, Benny Southstreet, Good Time Charley, Dave the Dude and Harry the Horse. Sixteen Runyon stories were turned into films, and his books are still popular today.

For most people, however, the Runyonesque magnum opus is Guys and Dolls, a musical that was pulled together after his death from three of his short stories written in the 1930s. Sadly Runyon was long gone before it opened in 1950 on Broadway, the winding showbiz street that he loved – and over which his ashes had already been scattered by Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. It’s no surprise that the scattering of anything from a biplane weaving between Manhattan’s skyscrapers was highly illegal, or that Rickenbacker, America’s most successful First World War fighter ace, was another of Runyon’s many male friends.

Damon Runyon lived and wrote with such brio that I had my doubts that I would find anything sufficiently Runyonesque when I visited New York in the winter of 2014. I went looking for Lindy’s first. Lindy’s was the Broadway deli where – allegedly – the line ‘Waiter, there’s a fly in my soup’ received its first witty riposte. Lindy’s was opened by Leo Lindermann and his wife Clara in 1921. The Jewish Mafia don Arnold Rothstein referred to it as his ‘office’ and conducted business there surrounded by bodyguards. The comedian Milton Berle always ate dinner at Lindy’s, and Runyon, long-time baseball correspondent for Hearst newspapers, was another regular, smoking, sipping coffee and scribbling in a notebook when he wasn’t talking the talk. Lindy’s, which features in Guys and Dolls as ‘Mindy’s’, was also famous for its cheesecake.

There is a new Lindy’s in Manhattan just one block south of Broadway on 7th Avenue. It advertises its ‘World Famous’ Cheesecake, serves you in old-fashioned booths and uses an Art Deco typeface on the menus, but it’s a new enterprise by the Riese Organization which took over the trademark in 1979. The original Lindy’s was half a mile away at 1626 Broadway, between 49th and 50th Streets. It closed in 1957 and became a steakhouse, but I was keen to see the site anyway. So I followed the street numbers down Broadway only to find a big, modern mixed-use block which, since 1992, contains Caroline’s, a top New York comedy club. It’s nice to know that humour continues at this address and evidently the 280-seat performance space received an architectural award, but it was hardly Runyonesque.

So I walked the short distance to the Stork Club at 3 East 53rd Street. From what I had read of Damon Runyon’s daily life in New York, he followed a triangular route in the canyons of skyscrapers just south of Central Park. The Stork was established on West 58th Street in 1929 by Sherman Billingsley, an Oklahoma bootlegger. After it was raided by agents of the Prohibition it moved twice, ending up on East 53rd Street, just east of 5th Avenue, in 1934.

The 5th Avenue Stork Club wasn’t big. It consisted of a dining room and bar and an oval ‘Cub Room’ which Billingsley built on for card games. There were no windows in the Cub Room, just wood-panelled walls hung with portraits of women, and a lot of smoke. On the door was a maître d’ known as Saint Peter who determined who was allowed to enter. Here Damon Runyon wrote, and added to the carcinogenic fug. In 1942 Hemingway claimed he was able to cash his $100,000 cheque for the film rights to For Whom the Bell Tolls at the club and thereby settle his bar bill, but that’s probably as true as most Hemingway stories.

In 1947, when Cosmopolitan published the last magazine article written by Damon Runyon, it was about the Stork Club, which he likened to London’s Mermaid Tavern in the days of Jonson and Marlowe: ‘A Mermaid Tavern complete with debutantes.’

When I found 3 East 53rd Street, nothing was there; nothing in the sense that after the club closed in 1965 it was demolished and an urban ‘pocket’ park was constructed by Bill Paley, chief executive of CBS, whose wife was adored by Truman Capote. Paley Park is a tranquil ivy-clad spot with a twenty-foot waterfall across its back wall that subtly drowns out the sound of traffic. It was difficult to believe that so much life and braggadocio once went on in this very small space.

Having struck out twice, I walked north to 101 West 57th Street with little optimism. This address had belonged to the Buckingham Hotel, where Runyon lived until his death in 1946. A favourite story he told against himself was about going out one morning and leaving a young lady still in his bed, and being hailed by a friend who pointed out that Runyon was not wearing a hat. Damon Runyon was known for his hats. So he returned to the Buckingham only to find his lady friend ‘playing house’ with the boxing champion Primo Carnera. Asked what a gentleman does when he finds his beloved in the arms of such a boxer, Runyon replied: ‘It’s all in the hat – you put it on and leave in a hurry.’

I knew the Buckingham had closed a few years earlier, so I expected to find the scene of this anecdote now a Starbucks or parking lot, but in fact as I turned the corner from 6th Avenue, there was the hotel where Ignaz Paderewski, Georgia O’Keeffe and Marc Chagall had at various times been Runyon’s neighbours. It’s now called The Quin (as in Quintessential New York), and had recently opened after a major refurbishment to create a twenty-first-century interior. But on the outside in all its brick verticality it is still 1929, the year in which the Buckingham opened. I could easily see Damon Runyon hurrying through those revolving doors in search of his hat, and coming back out even faster.

THE ALGONQUIN HOTEL, NEW YORK – DOROTHY PARKER (1893–1967)

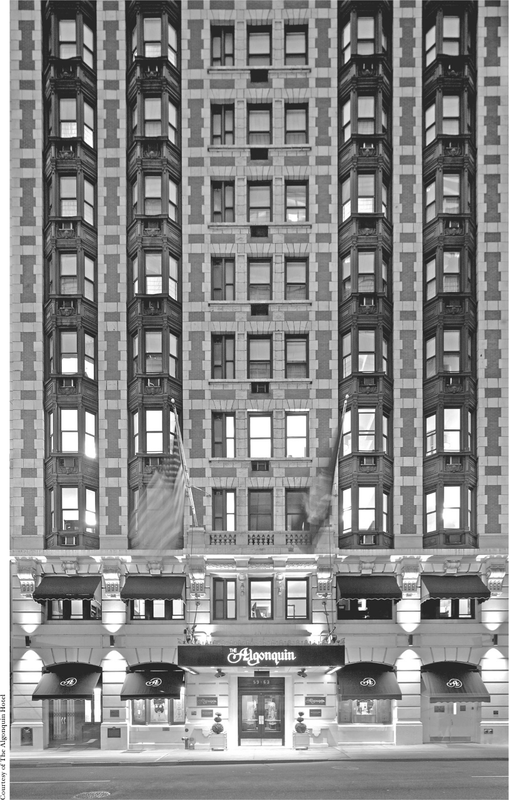

The Algonquin Hotel opened in 1902. Its location on West 44th Street was close to many New York theatres. This was originally intended as a residential hotel – like the Chelsea – but the proprietors soon discovered that rooms let commercially at $2 a night were more profitable. In the 1920s the hotel became linked with a coterie of witty and acerbic writers, including Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley and Robert E. Sherwood. But it will always be associated for most of us with Dorothy Rothschild Parker. Mrs Parker was one of the youngest members of the waspish Round Table who lunched at the ‘Gonk’ as often as six days a week for nearly ten years in the 1920s. She was also one of the few women in the group which awarded itself various nicknames over the years, including ‘the Vicious Circle’.

The Circle started off dining in the hotel’s Pergola Room (now called the Oak Room). When it grew too large and rowdy, the owner-manager, Frank Case, moved them into his main dining room, the Rose Room, seating them at a round table which later gave its name to the Round Table Restaurant.

When she was first invited along as drama critic of Vanity Fair, Dorothy Parker was 25 and on the verge of becoming famous both as a writer and as the prototype for other people’s wise-cracking female characters. Philip Barry created a ‘Dottie’ clone in Hotel Universe (1932), as did George Oppenheimer in Here Today (1932), and George S. Kaufman in Merrily We Roll Along (1934). Kaufman’s representation of a heavy-drinking Mrs Parker precipitated a breach between Dottie and her former Round Table compatriot. She got a revenge of sorts, however, outstripping him in fame, with Kaufman admitting eventually: ‘Everything I’ve ever said will be credited to Dorothy Parker.’

Mrs Parker also lived at the Algonquin from time to time. In 1924 after she split – for the second time – from her husband, the handsome WASP stockbroker Eddie Pond Parker, Dorothy moved temporarily into a furnished suite on the second floor. She lived there again after the Vicious Circle disbanded in 1929, and in 1932 she attempted suicide in her room at the Algonquin. (Mrs Parker attempted suicide three times. Being brittle, female and funny can exact a toll.)

I wasn’t sure that the Algonquin existed any more, but in 2012 I found out that it was undergoing a major refurbishment, and arranged to be in New York when the press were invited round. The new Algonquin was slated to have over twenty new suites named after its famous lunchers. There would be a James Thurber Suite and a John Barrymore Suite, aptly just above the Blue Bar (it was Barrymore who in 1933 convinced Frank Case to put blue gels over the lighting in the bar because he believed they improved one’s appearance). There was also going to be a Dorothy Parker Suite, although no one was sure if it would be one of the actual rooms in which she lived – and attempted to die. Up on the tenth floor where Frank Case and his wife raised two children in Suite 1010, a new Noël Coward Suite would be named after one of the occasional outsiders to grace the Algonquin’s Round Table.

My interest was not in the bedrooms, however, but in the Round Table Restaurant, where Mrs Parker probably thought up – and certainly delivered – some of her best one-liners. The Algonks loved charades, pranks and parlour games. One of these was called ‘I can give you a sentence’. Given the word ‘horticulture’, Dorothy Parker famously riposted: ‘You can lead a horticulture but you can’t make her think.’

Much of what we think of as classic Dorothy Parker wit was written during her Algonquin days. Here she collaborated with playwright Elmer Rice to create Close Harmony, which opened on Broadway in 1924. Her first volume of verse, Enough Rope, came out in 1926 and the second, Sunset Gun, in 1928. She also wrote short stories, such as ‘The Garter’, which was published in The New Yorker in 1928, and ‘Big Blonde’, which won the O. Henry Award for best short story of 1929.

In 1934 Dorothy moved on to Hollywood with her second husband. She earned a fortune writing for the movies, but that was not the Mrs Parker I was looking for. I wanted the wisecracking Queen of Literary Manhattan.

So it was, in 2013, a month after the completion of the $5 million refurbishment, that I went to lunch at the Algonquin. Tales of the nine-month building work sounded alarming. The old plumbing, which had been built into the walls as the hotel was constructed, had had to be dug out and replaced, pipe by pipe. But I was pleased to see that the Round Table Room was refurbished with dark wood panelling and studded leather dining chairs that recalled the early twentieth century without being too precise. Strict Art Deco lines had been kept for the Blue Bar but, alas, there was no large round table, nowhere where you could pull up your chair and try to be witty. Nevertheless there is a very good painting on display by the young New York artist Natalie Ascencios. Her ‘Vicious Circle’ shows Harold Ross in the foreground, reading The New Yorker with Alexander Woollcott leaning over his shoulder. Dorothy Parker sits, poised and brittle, to the left of the picture.

To eat I ordered Matilda’s Crab Cakes (named after the hotel’s cat, now in her third incarnation). It was John Barrymore who made the Algonquin cat an institution by renaming Frank Case’s stray moggy ‘Hamlet’ in the 1930s. There have now been seven Algonquin Hamlets and three Matildas.

Lunch was very enjoyable but I came away with the feeling that if the Algonks were reincarnated today they’d eschew this room as too respectable, too attuned to modern sensibilities. These days NYC health regulations have banned Matilda from the dining areas.

There’s no doubting the frisson of being in the very room where Dorothy drawled her witticisms. She was particularly hard on actresses, claiming that Katharine Hepburn ‘runs the gamut of emotions from A to B’ and that Marion Davies ‘has two expressions: joy and indigestion’. Of Edith Evans she once claimed, ‘Edith looks like something that would eat its young’, but my favourite remains her view of the writer’s profession: ‘I hate writing, I love having written.’ Like the very best wit, that contains so much truth.

HOTEL CHELSEA, NEW YORK – DYLAN THOMAS (1914–53)

For generations the Chelsea was New York’s most glamorously notorious hotel. Dylan Thomas’ death in 1953 from alcohol poisoning, pneumonia and what was referred to as ‘a severe insult to the body’ did a lot to cement its dubious reputation. Cheap rooms and 70 years of benign, scarily laissez-faire management by the Bard family made the Chelsea a magnet for generations of bohemians in the Big Apple.

The twelve-storey red brick city block was built in 1884 by Philip Hubert, an idealistic Anglo-French immigrant who hoped that at the Chelsea he could design a truly socialist building in which the rich and poor could live in harmony.

By 1905, however, this bold experiment on West 23rd Street had failed and the Chelsea was reinvented as a hotel. In its 102 years of life, right up until the Bard family were driven out of business in 2007, it proved irresistible to writers, artists and musicians. Frida Kahlo, Mark Rothko, Edith Piaf, Brendan Behan, Arthur C. Clarke and Leonard Cohen all stayed at the Chelsea. Arthur Miller lived here for six years in the 1960s after his break-up with Marilyn Monroe and claimed you could get high just by standing in the hotel lifts and inhaling the marijuana smoke. Jack Kerouac wrote sections of On the Road while staying at the Chelsea. A hotel legend runs that in March 1953 Kerouac met his friend Gore Vidal at the Chelsea, both intent on meeting up with the poet Dylan Thomas, newly arrived from Wales. Failing to find Thomas, the two men got very drunk and ended up spending a passionate night together, an event that Kerouac later recorded in a bowdlerised version in his 1958 novel The Subterraneans.

Dylan Thomas actually arrived in New York on 21 April of that year. He had promised to hand over his new play for voices, Under Milk Wood, on arrival but it was finished only on the day of the first performance three weeks later. Liz Reitell, an assistant at the Poetry Center on East 92nd Street where the work was being premiered, had to lock the harddrinking Dylan in his room until it was completed. Liz was also Dylan’s American girlfriend by this stage, but the poet was simultaneously writing desperate love letters to his wife Caitlin in Wales. Dylan Thomas’ life was often a mess, but it was spinning wholly out of control at this time. One night he fell downstairs drunk and broke his arm, and when he and Liz went to see Arthur Miller’s The Crucible at the Martin Beck Theatre on West 45th Street he started jeering and swearing at the actors and was asked to leave.

Back in Wales that summer, Dylan found he couldn’t work. He lost a version of Under Milk Wood that he was writing for the BBC in a Soho pub and fled once again to New York, where Liz took him back. Unfortunately he couldn’t get the room he wanted at the Chelsea and he complained that in the small room he was given at the rear of the hotel, the cockroaches had teeth. This visit was even more erratic than the previous one. Despite Stravinsky wanting to work on an opera with him, and a lecture agent offering $1,000 a week if he’d go on the circuit, Dylan drank, argued with everyone and screamed in the night as terrors engulfed him. On 4 November he came back from his last drinking binge and announced to Liz that he had just drunk eighteen whiskeys. He then fell asleep and on 5 November muttered, ‘After 39 years this is all I’ve done’, before slipping into a coma. On 9 November he died in St Vincent’s Hospital.

Today a brass plaque outside the Hotel Chelsea records that here ‘Dylan Thomas laboured his last and sailed out to die’. It’s a poetic way to put it. I visited the hotel after it had been sold to developers in 2007 and long before the refurbishment began to turn it into the flagship of the shortlived Chelsea Hotels Group. Its long pink and white awning still stretched into the street and inside there was a scattering of old armchairs across the tiled lobby. The walls above a small reception booth were almost obliterated with artwork, not all of it good. There was a large pink papier-mâché female figure hanging from the ceiling. Some of the cubbyholes behind reception were jammed full of uncollected mail for guests and residents, but many had already departed.

The lobby with its mismatched chairs and abandoned newspapers reminded me of a student common room from the 1960s, and not a very tidy one at that. I asked if I could have a look at the famous wrought-iron staircase that winds up the hotel’s lightwell. Officially tours had to be booked but the man behind reception just shrugged. So off I went on my own. The staircase is a robust piece of nineteenth-century construction that matches the balconies on the outside of the hotel. Looking for Room 205 where Dylan drank his last, I found some graffiti etched into the badly-painted plaster that commemorated punk rocker Sid Vicious who murdered his girlfriend Nancy Spungen here in 1978. By then the building had slipped from notoriety to legendary squalor.

If the hotel ever reopens, it will of necessity present a cleaned-up version of its wild literary past. There aren’t enough roaring boys out there these days to make a Chelsea Mark II profitable. But there are many other sights connected with Dylan that haven’t changed. Liz Reitell recorded that for a few days after checking into the Chelsea in October 1953, Dylan had hardly drunk and enjoyed going for walks with her around the various villages of New York. He liked Patchin Place, a gated cul de sac near Washington Square Park where he used to visit the poet e e cummings. Dylan also liked St Luke in the Fields, a small church built on Hudson Street in 1822. It would be here that the poet’s memorial service took place on Friday 13 November 1953, immediately before Caitlin Thomas took his body back to Wales. The congregation included Caitlin, e e cummings, William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams and Edith Sitwell. Best of all Dylan liked the White Horse Tavern, a drinking hole for longshoremen a few blocks north on Hudson Street that was built in the 1880s and reminded him of a Welsh dockside pub. Today it is still decorated as the poet last saw it.

Dylan Thomas was one of those writers who played up to the part of the demonic, drink-fuelled roaring boyo. Sadly, he died that way too. No Dylan pilgrimage can entirely avoid a strain of melancholy.

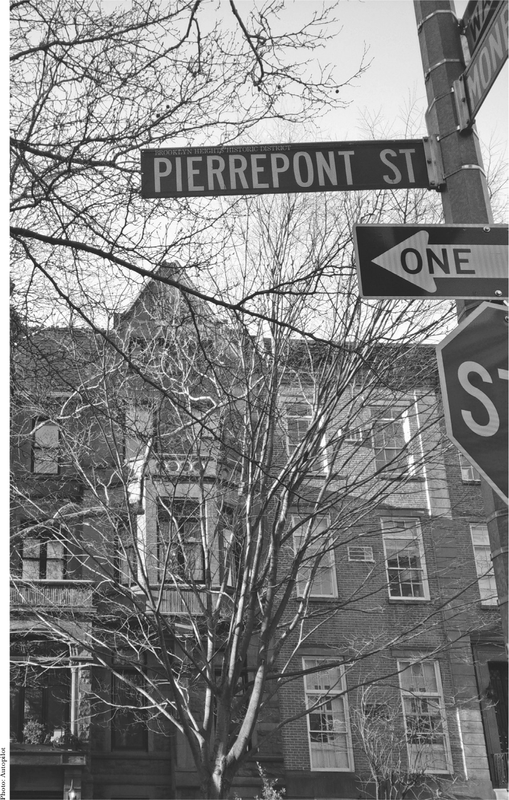

PIERREPONT STREET, NEW YORK – ARTHUR MILLER (1915–2005)

Brooklyn Heights sits directly across the East River from Manhattan and in 1965 became New York’s first protected Historic District. Long before then, it had already made its own kind of history as the city’s premier bohemian neighbourhood. Henry Miller, author of Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, lived in Brooklyn Heights in the 1920s. He moved into 91 Remsen Street in 1924, only to be evicted the following year for non-payment of rent. Novelist Thomas Wolfe lived on Montague Terrace in the 1930s, as did W.H. Auden in 1940. Truman Capote rented the basement apartment at 70 Willow Street for ten years in the late 50s and early 60s. Here he finished Breakfast at Tiffany’s and wrote In Cold Blood, as well as penning the essay ‘Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir’, which includes a line still much enjoyed by locals: ‘I live in Brooklyn. By choice.’

But for me the most interesting and productive address in this tree-lined neighbourhood is 102 Pierrepont Street, a house divided into apartments where in 1943 and 1944 young Norman Mailer lived with his parents when home from serving in the Second World War. Meanwhile, in the wood-panelled duplex below lived a writer, eight years his senior, who was exempted from war service by an old sporting injury and struggling with his career. Arthur Miller had moved in recently with his first wife Mary and young daughter, and was seriously considering abandoning drama. In November 1944 his play The Man Who Had All the Luck ran for just four performances at the Forest Theatre on Broadway. Over the next three years in Pierrepont Street, Miller worked to discover his dramatic voice, which he did finally in 1947 with All My Sons. This play about a factory owner accused of making faulty parts for military planes ran for almost a year at the very same Broadway theatre (albeit renamed the Coronet) and won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award.

Norman Mailer, returned from serving in the Philippines and working on his war novel, The Naked and the Dead, went to see it and later recalled meeting Miller by the groundfloor mailboxes. ‘I could write a play like that,’ Mailer told Miller. Arthur Miller just laughed. Mailer later recorded: ‘I can remember thinking. This guy’s never going anywhere. I’m sure he thought the same of me.’

By 1949 Miller had moved to Grace Court, a cul de sac overlooking the East River where he finished Death of a Salesman, the big theatrical success of that year, winning both the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the Tony Award for Best Play. Miller was able to purchase the townhouse at Grace Court and even sublet the bottom two floors to the president of the Brooklyn Savings Bank, thereby further stabilising his income (although the playwright ultimately grew tired of being a landlord).

In 1951, while trying to sell a screenplay to Hollywood, Arthur Miller had a brief extra-marital affair with Marilyn Monroe and afterwards kept in touch with her. In 1956, after writing The Crucible, he left his wife Mary for Marilyn, selling Grace Court to W.E.B. DuBois, the African-American activist.

By the early 1960s Arthur Miller’s rollercoaster years married to Marilyn were over and he holed up across the river in New York’s Fashion District at the bohemian (to put it mildly) Hotel Chelsea, where he lamented there wasn’t even a vacuum cleaner.

One hot sunny day in August, when the trees offered islands of welcome shade on Pierrepont Street, I went to look at number 102. I also passed by Grace Court, but it was Pierrepont Street that drew me because it was here that his career took off. I suppose it was the appeal of seeing where Arthur Miller licked his wounds after the failure of The Man Who Had All the Luck and turned his career around, writing All My Sons while Norman Mailer slept upstairs in his parents’ spare bedroom.

What surprised me was that 102 is the only house in this long row of Brooklyn Brownstones with a white facade. It seems to take its colour scheme from the marble of the courthouse opposite. The position of the five floors, windows and balconies matches exactly those of the two adjacent houses and all three share a roof as part of one development, but balconies and windows are not original. In fact No. 102 has been modernised at some stage in the twentieth century.

I liked the symbolism in this: Arthur Miller, the man who modernised the American play, working in a house that itself was breaking with local traditions. I also came away thinking there was something symbolic in how Arthur Miller kept on moving house. He had five homes in Brooklyn between 1940 and 1955, a restless fifteen years when he was trying to find himself as a writer. And there’s something horribly symbolic too in the fact that he then crossed the river to Manhattan where he ended up living in Marilyn Monroe’s Waldorf Tower apartment before spiralling downwards to recuperate in Hotel Chelsea in the 1960s.

Arthur Miller’s success continued, but here in Brooklyn Heights was where the great work was done.

LOWELL, MASSACHUSETTS – JACK KEROUAC (1922–69)

‘Everyone goes home in October,’ wrote Jack Kerouac and so one chilly autumn in New York I decided to do just that – not to my home, but his. It was a four-hour drive north along Interstate 95 to Lowell, reversing the route that Jack would have taken when he headed on the road to Columbia University in 1940.

Jean-Louis Kérouac (known as Ti’Jean in his French-speaking family) was born and raised in Pawtucketville on the north side of the Merrimack River in the old cotton town of Lowell. Eventually he returned to live out his last years here, drinking noisily and growing maudlin. He died in Florida but was brought back and buried in what he always referred to as ‘My Lowell’.

Lowell is very quiet these days, and picturesque in a post-industrial way. I got there mid-morning as the sun was illuminating a huge rooftop sign over the Lowell Sun newspaper building. Jack Kerouac, the man who gave voice to America’s Beat Generation, worked here 75 years ago. Today it stands huge and empty.

Bright sunlight was also picking out the large clock hanging outside Lowell High School. For four years Jack was a student in this extremely long, yellow brick Art Deco building. He claimed he used to smoke beneath its ‘boxlike’ clock.

Once upon a time Lowell had been hugely important to the Massachusetts economy, with a population big enough to bring Dickens here on a reading tour. Then the Depression ripped the industrial heart out of the town. By the 1940s when Jack first headed out ‘on the road’, the city was so poor it couldn’t afford to demolish its empty old buildings. But this has made Lowell special today. It doesn’t look like all the other cookie-cutter American cities with identikit shopping malls. The nearest Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donuts are a mile out of town.

Although Jack Kerouac criss-crossed America in the 1950s, questing for something always beyond the horizon – even ending up in Morocco with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs at one point – he claimed Lowell remained the most interesting place he knew. Many of his early novels were set here.

I drove on, over the red metal bridge linking the centre of Lowell with Pawtucketville, to look at the simple wooden house where Jack was born and where he made his first stabs at thinly-veiled fiction. No. 9 Lupine Road is a modest two-family house with verandas top and bottom and two front doors side by side, one for the family downstairs and one for the family up top. Jack’s parents started off down below but he was born after they moved above. Upstairs was more desirable as heat rises, and in Massachusetts winters you need all the heat you can find.

Crossing back over the Merrimack Canal I came to the New City Hall and the Pollard Memorial Library where Jack – playing hooky from school – determined to read every book in stock. Jack Kerouac was a consummate absentee. He skipped school for 40 days in his final year but still gained a place at Columbia University.

I pushed open the two sets of double doors to enter a smart wood-panelled reading room with chandeliers. ‘I saw that my life was a vast glowing empty page,’ Kerouac recorded. ‘And I could do anything I wanted.’

Looking in the library’s local history section I read that Lowell went through some bad times in the 1940s and 50s. It had a reputation for drugs and violence and soldiers from Fort Devens came here looking – successfully – for prostitutes. But this library would inspire a young man with literary aspirations.

At the Patrick J. Morgan Cultural Center on French Street I saw Jack’s typewriter on which in 1951 he pounded out his masterwork, On the Road. It’s a classic black skeletal Underwood with the keys like little white petri dishes and the H and J badly discoloured. On the Road was finally published in 1957 and made Jack a literary star. Sadly success did not make him happy.

Jack bequeathed a lot to Lowell, including a whole archive of his own papers that are still being sifted. Despite his celebrity and restlessness he was repeatedly drawn back to this empty city with its huge, idle red-brick cotton mills. The saddest thing I read here was one of his friends recording that the last time Jack visited Lowell, ‘he wanted to be a big kid again and play with the boys for a few days. But the others had grown up, had responsibilities, and Kerouac went away disappointed.’

Jack, like many twentieth-century writers, drank heavily. When he moved back to Lowell he drank at the Sack Club on Market Street. He also drank at Nicky’s strip joint on Gorham Street and it was the owner’s sister, Stella Sampas, whom he took as his third wife in 1966, confirming his return home. Nicky’s is now Ricardo’s Café Trattoria and, when I pulled over in my hire car, it looked much more respectable these days although it was shuttered and not yet open for lunch.

From here I thought about heading to the Kerouac grave, but first I walked to ‘Funeral Row’, Jack’s nickname for Pawtucket Street on which still stand Lowell’s four funeral homes. Three of them were Irish and one French, Archambault and Sons, which would be the site of Kerouac’s wake in 1969.

By early afternoon I made it to Edson Cemetery and the simple stone which records Jack’s dates and adds the epitaph ‘He Honored Life’. Yes he did, in his own troubled way.

* * *

TOULOUSE STREET, NEW ORLEANS – TENNESSEE WILLIAMS (1911–83)

Certain cities seem to attract writers. In the early twentieth century a lot of authors were drawn to Paris where they could drink cheaply and sexuality was only loosely policed. Berlin under the Weimar Republic offered similar inducements, and so for decades has New Orleans, where – uniquely in the United States – you can stand on a street corner with an alcoholic beverage in your hand and not get arrested. This freedom still pertains today (which can make it very difficult walking through the French Quarter because the streets are clogged with Americans taking full advantage of this uncommon liberty).

Literary greats to enjoy New Orleans’ hospitality include William Faulkner, Truman Capote, Kate Chopin, Sherwood Anderson and John Steinbeck. Ernest Hemingway, Lafcadio Hearn, Eudora Welty and Anne Rice also drew inspiration from New Orleans, as did Thomas Lanier (‘Tennessee’) Williams III.

It was inevitable that I’d be drawn to a city with such a pedigree for writing and alcohol. On my first night in New Orleans I was seriously jetlagged but my American in-laws had insisted I try the famous Gumbo Shop. The gumbo was satisfyingly thick and sustaining after my international flight, a domestic hop from Atlanta, and then a hire-car journey into N’Awlins.

What I didn’t realise as I consumed this rich dark stew was that I was already in Literary New Orleans. Next door to the Gumbo Shop at 632 Rue St Peter was a shop called Fleurty Girl. And above that was where Williams worked on A Streetcar Named Desire. In my jetlagged state, I had missed the dark metal plaque.

Like many of these French Quarter houses, 632 Rue St Peter is a brick structure with white door frames and the most enormous roofed balcony above. The plaque explained that this was the Avart-Perretti house built in 1842, and the long-term home of the Italian painter-cum-anarchist Achille Peretti. He died here in 1923.

In 1946 Tennessee Williams moved in to rewrite his script of Streetcar. He had already emerged from obscurity in 1944 with The Glass Menagerie but when Streetcar opened in December 1947 it was a huge Broadway success, immediately confirming Williams as one of the greatest American dramatists of his generation. What interested me, however, were the years before his first two successes.

Williams had arrived in New Orleans at the end of 1938, around the same time as he adopted ‘Tennessee’ as his professional name. Though born in Columbus, Mississippi, the playwright honoured his father’s Tennessee pioneer forebears in that choice. Unfortunately Cornelius Coffin Williams of Mississippi did not think well of his son’s theatrical aspirations, nor of his sexual orientation, and teased him mercilessly for his effeminate qualities, calling him ‘Miss Nancy’.

A week after his arrival the 27-year-old found himself an attic apartment over a shabby restaurant at 722 Toulouse Street. Here in one of the oldest sections of the Vieux Carré he began work on an autobiographical play about a young man struggling with his sexuality and his desire to be a writer. He called the play Vieux Carré but laid it aside to work on Battle of Angels, his first professionally-produced play, which failed spectacularly when staged in 1940 but was reworked successfully in 1957 as Orpheus Descending.

This was the building I wanted to see. Toulouse Street is just three blocks from where I was staying at the Monteleone, so the next day I walked round to look at the garret where an uncertain young playwright proved that he could make money out of writing, pulling together the painful autobiographical strands that would eventually form The Glass Menagerie.

Today 722 Toulouse Street is part of the Historic New Orleans Collection complex and contains the archives of the association, which functions as a museum, research centre and publisher, dedicated to preserving the city’s heritage. Toulouse Street itself is lined with some of New Orleans’ original single-storey eighteenth-century cottages, but No. 722 is two storeys, with the garret making it three.

Entrance to the Historic New Orleans Collection is actually on Royal Street, which is where I picked up a brochure that told me – among many other things – that Tennessee’s first home in New Orleans had been built in 1788 by a Mr Louis Adam but by the 1930s it was in a sorry state and functioning as a boarding house.

At the back of 722 there is a staircase – partly external – that leads up to ‘Tennessee’s room’. It isn’t open to the public but I managed to see around. There’s a lot of storage up there but the layout recalled the description Tennessee wrote down when he resumed work on Vieux Carré in 1977: ‘A curved staircase ascends from the rear of a dark narrow passageway from the street entrance.’ Up in the attic there were indeed ‘a pair of alcoves facing on to Toulouse Street’; Tennessee claimed these were partitioned off by plywood in his day to make two rooms. In Vieux Carré the young writer lives in one of these attic rooms, and an old painter, dying of tuberculosis, in the other. At the back of the attic, separated off by a narrow hallway, was a studio with a skylight where lived two more people. In Vieux Carré they are Jane, a New Rochelle society girl dying of leukaemia, and her sexually ambiguous lover, Tye. In its barrenness, Tennessee wrote, ‘there is a poetic evocation of all the cheap rooming houses of the world’.

Vieux Carré was not a financial success but for Tennessee enthusiasts it’s a tellingly autobiographical play about those early days in New Orleans. In that store-room I caught just a hint of the time when this was Tennessee’s room. I felt I could have stayed here, moved a few boxes and done some writing myself. New Orleans appeals to the writer in us all.

HOTEL MONTELEONE, NEW ORLEANS – TRUMAN CAPOTE (1924–84)

Truman Capote often claimed he was born at New Orleans’ Hotel Monteleone. Sometimes he even claimed that he was born at its rotating Carousel Bar. This was definitely untrue, as it wasn’t constructed until 1949. What we do know is that Truman’s seventeen-year-old mother was staying at the Monteleone at the time of his birth, but the hotel got her to the Touro Infirmary in time for the little literary genius to be delivered. However, there remains a poetic truth in the statement. The Carousel Bar at the Monteleone could be seen as Truman’s spiritual home and the hotel as his godfather. Truman needed godfathers. A metaphorical search for absent fathers can be traced through much of his literature.

Glitzy, bustling, and remarkably tall for New Orleans, the Monteleone is like a piece of New York hotel real restate transplanted to this European city on the banks of the Mississippi. It was developed from 1886 onwards by Antonio Monteleone, an Italian immigrant shoemaker whose family still owns the 600-bedroom block. Massively enlarged in the 1950s and 60s, the Monteleone remains the only high-rise in the old French Quarter. With its roots firmly in the Beaux Arts movement, it continues to be the place to stay in New Orleans. Tennessee Williams mentions it in The Rose Tattoo and Orpheus Descending, Eudora Welty cites it in A Curtain of Green, Hemingway refers to it in his short story Night Before Battle, and Rebecca Wells features it in The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood.

According to Truman, during a very lonely childhood his mother would sometimes lock him in her suite at the Monteleone while she went out partying for the evening. Later, after his parents’ divorce, when he was sent to live with his cousins in Alabama, Truman would still come back to the French Quarter for holidays. In the 1940s, as a beautiful blond young man with literary ambitions, Truman worked on his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms at 711a Royal Street, New Orleans. Thanks to word of mouth and Truman’s own conspicuous showmanship, the book was a runaway literary success even before it was printed in 1948. Tellingly, the story focused on a lonely and slightly effeminate thirteen-year-old boy sent away from New Orleans to live with the father who had abandoned him at the time of his birth.

Today you can find where Truman wrote Other Voices, Other Rooms between the hat shop at 709 Royal Street and the shop for locally printed T-shirts at No. 713. There is a passageway that runs down past an old dark staircase leading up to apartments, and into a brick courtyard. Antiques are sold in the passageway and impeded my way, but I found the courtyard itself, screened off by two large shutters with the words ‘PRIVATE COURTYARD – PLEASE NO PHOTOS’ neatly chalked on one of them. Clearly, a lot of pilgrims come here. Nevertheless I peeped over the shutters and through the gap between them to see a small white-balconied house surrounded by plant pots where Truman wrote his first bestseller. From old photos I’ve seen, it was definitely scruffier – and cheaper – in his day. Today it’s about as bijou as even Truman would have wanted.

Truman Capote continued to visit New Orleans, sometimes to retreat from the fame he so strenuously courted – especially after the film of Breakfast at Tiffany’s made him a twinkling star in the 1960s. He also lived for a while in Rome in Via Margutta very close to where Keats died, but he retained a fondness for the French Quarter. In a 1981 interview in People magazine, long after the non-fiction novel In Cold Blood had made Truman a major force in modern literature, he said: ‘I get seized by a mood and I go. I stay a few weeks and I read and write and walk around. It’s like a hometown to me.’ He then went on to praise St Louis cathedral, the Caribbean Room at the Pontchartrain Hotel, and the Bourbon Street burlesque club Gunga Den as some of his favourite sights.

Like Truman I have enjoyed sitting on one of the bar stools at the glitzy Carousel Bar, which moves on 2,000 rollers and looks remarkably like a fairground carousel. It makes one very slow rotation every fifteen minutes. It’s easy to imagine him perched on one of these stools, his legs dangling and his strange, high-pitched voice dominating the bar.

Today Truman would probably be thrilled to know that there is a Capote Suite at the Monteleone. It’s one of five literary suites that the hotel created in honour of its most famous literary guests – Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Hemingway, Welty and Truman. When I got myself invited to take a look I thought it rather restrained and its curtains over-ruched. My wife’s New England grandmother would like it, but the décor is probably a wise choice: not all guests at the Monteleone would share Truman Capote’s unique talent and florid taste.