SHIOMI NAWATE STREET, MATSUE, JAPAN – LAFCADIO HEARN (1850–1904)

My wife is an enthusiast for all things Japanese so we were in Matsue for her. It’s a sweet, undersized city on the north coast of southern Honshu with a small castle and boat tours of the inner and outer moats. There is also a samurai residence to visit and the former home of an author who deserves to be better known in the West. Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was born in Greece to an Irish surgeon in the British army and an illiterate Greek mother. Via a series of misfortunes he was abandoned by both parents and most of his relatives. He ended up being raised in Ireland by a very straitlaced aunt and then, as a young man, living rough in London.

At the age of nineteen Lafcadio was sent to America by a relative who thought his in-laws over there might help out. They didn’t, but the young man did well as a journalist in Cincinnati where he was known for sensationalist articles and florid descriptions. In due course he moved to an editorial post in New Orleans, where his bright, enquiring mind helped him to write successfully about Creole culture and even produce a local cookbook. The city still preserves his house on Cleveland Avenue.

To find Lafcadio’s home in Matsue we followed signs showing a baggy little man carrying tattered suitcases walking ahead of us. This was one of his own self-deprecating cartoons. On the way my wife filled me in enthusiastically on Lafcadio’s life. As a schoolboy he lost an eye in a sporting accident. Later he was sacked by one set of employers for marrying an African-American woman, and another time was banished on a lengthy assignment to the West Indies.

By the time he reached Japan in 1890, Lafcadio Hearn had packed a lot of restless living into his first 40 years. Here he finally, for the first time in his life, found a home. Hearn embraced Japan, married the daughter of a local samurai, taught successfully at the local school, and set about translating Japanese stories into English. He and his wife worked on this project together, she reading tales out to him in pidgin English and he working them into something readable. In the last ten years of his life he produced fifteen books about Japan. Some were translations of ghost stories and legends, others were accounts of his travels and observations about his adopted country for an excited Occidental public. Taking Japanese citizenship (he is known as Koizumi Yakumo in Japan, and is regarded with much affection), Lafcadio Hearn probably did more than any other western writer to make Japan accessible and not just exotic to curious Westerners.

The house where he lived in Matsue has been preserved as a designated Historic Site since 1940. It stands on Shiomi Nawate Street near a sharp bend in the Inner Moat and is traditionally constructed of dark wood with tatami mats and shoji screens. In its grounds stands the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum, which was established in 1933 to explain his work. More than 150,000 people a year visit this shrine to the undersized, half-blind man who found a home in Japan.

We paid our 300 yen to look around, entering through a courtyard of white pebbles. The house was small and bare except for a reproduction of his simple Western-style writing table and a chair, both with the legs linked by wooden runners so they could be slid, like a sledge, across the tatami without scratching it. There was a big shell on the desk and his magnifying glass, which was huge. His one remaining eye was in poor condition.

Old photos showed the room much more cluttered with Victorian bric-a-brac and bookcases everywhere when Lafcadio lived here, but I think the sense of serenity was probably accurate. He stopped travelling when he reached Japan. I could understand why. Out in his small garden – which, unlike the house, has not been refurbished – a very old, rather weary tree was supported by a stone and the pond was full of bright green lilies. I felt I could sit here a while, and in fact we both did.

Every year on 26 September, the anniversary of his death, an English speech recitation contest and a haiku contest are held in Matsue to honour Lafcadio. He is also commemorated in a statue that I spotted across the road as we left. All photos I have seen of the author show him in profile, because he was embarrassed by his missing eye, but this bust has him looking you in the face, both eyes open and clear. It seemed a nice, very Japanese way to honour Koizumi Yakumo.

THE CATHAY HOTEL, SHANGHAI – GEORGE BERNARD SHAW (1856–1950)

By the time George Bernard Shaw arrived in Shanghai he was – thanks to relentless self-promotion – one of the most famous literary men in the world. The tall bearded Irishman’s trajectory was cleared for him by the disgrace of his contemporary Oscar Wilde. Shaw was a Nobel prize-winning playwright, novelist, essayist and polemicist. He was a Fabian, a free-thinker and a stout defender of the rights of the working classes. He was also co-founder of the London School of Economics, had helped to establish the New Statesman magazine and was a great enjoyer of life. ‘I’m only a beer teetotaller,’ Shaw once remarked. ‘Not a champagne teetotaller.’

Approaching his eightieth birthday, GBS set off in December 1932 on a cruise to the Far East on board the Empress of Britain. He had speaking engagements booked in Manila, Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as a lunch in Shanghai with Madame Sun, widow of Sun Yat Sen, the founding father of the Republic of China. Later – after a rather hairy plane ride over the Great Wall of China, where (to his horror) he saw Chinese and Japanese troops shooting at each other – he would cross the Pacific to America.

The day before his arrival in Shanghai, its Rotary Club members – not the most liberal of expatriates – declared Shaw a ‘blighter’ and an ‘ignoramus’ and resolved not to acknowledge his presence in their lucrative colony. Shaw had other plans anyway. Madame Sun had invited him to her spacious 1920s villa at 29 Rue Molière in the French Concession and here Shaw lunched with some of the leading writers and intellectuals of 1930s China. This was a period of great global turbulence – a time in which foreign powers were pushing rival claims on China – but GBS was adamant that he had not come to impose solutions: ‘It is not for me, belonging as I do to a quarter of the globe which is mismanaging its affairs in a ruinous fashion to pretend to advise an ancient people striving to set its house in order.’

At that famous lunch on 17 February 1933 Shaw met with the co-founders of the Chinese League for Civil Rights, as well as the Soviet spy Agnes Smedley, the editor and critic of the nationalist government Lin Yutang, and the American journalist Harold Isaacs. The last two were later painted out of the commemorative photograph taken that day – Lin because he moved to America in 1935, and Isaacs because in 1938 he published a damning history of the Chinese Revolution.

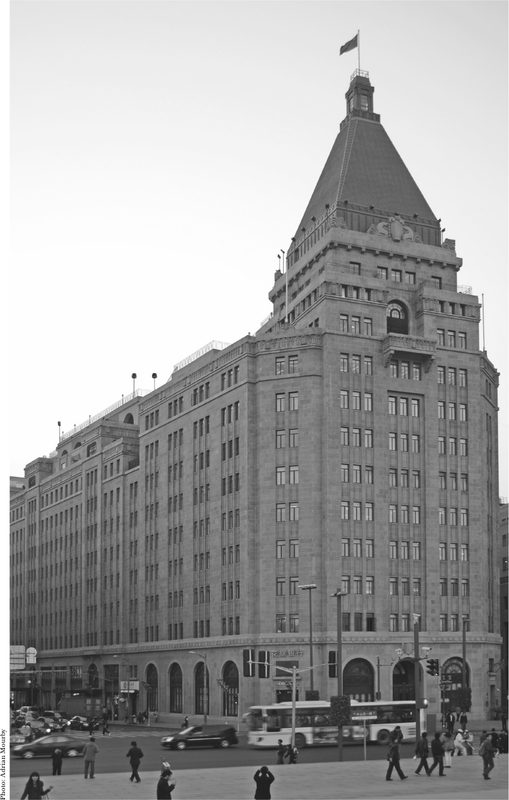

The official record of Shaw’s visit ends after his departure from the PEN Club meeting that followed the lunch, but from the record of Mr Yang Meng Liang, who wrote his memoirs in 2005, we know that Shaw then stayed on at the Cathay Hotel (now Shanghai’s Peace Hotel). At the time Mr Yang worked as hotel doorman.

‘In the period of the Anti-Japanese war I was a very humble attendant at Cathay hotel. I saw many different people there. I still remember what the foreign supervisor said to us, “Keep on your work carefully. You know finding 100 guys is much easier than finding 100 dogs.” At that hard time, we had to bear the insults and the hard work. I was still a doorman in 1933 when the Irishman, George Bernard Shaw came to Shanghai and visited our hotel.’

Today the Peace Hotel is very proud to have welcomed celebrities like Charlie Chaplin, Noël Coward and Shaw. It also hosted the young, as yet unknown Christopher Isherwood, who in 1938 wrote enthusiastically about the availability of sex in Shanghai, adding: ‘You can dance at the Tower Restaurant on the roof of the Cathay Hotel, and gossip with Freddy Kaufmann, its charming manager, about the European aristocracy or pre-Hitler Berlin.’

However, these days the Peace Hotel cannot tell you where Shaw – or any of these literary greats – actually stayed, or which of them met with Sir Victor Sassoon who had built the hotel in 1926. He had a private dining room on the eleventh floor in which visiting celebrities were entertained below the hotel’s famous, green conical tower.

Much of the hotel’s archive was lost in 1949 after Sir Victor had slipped away to a life in the Bahamas as Mao’s Communist army swept into Shanghai. The old Cathay Hotel was nationalised and then turned into offices. In 1952 it was reopened as a hotel and in 1956 it was renamed Peace Hotel, a cruel appropriation of a seemingly innocent word, given the belligerent behaviour of the revolutionary Chinese government.

After the opening up of the Chinese state in the 1980s, following Deng Xiaoping’s declaration that it was ‘glorious to get rich’, the Peace Hotel was restored to much of its former Art Deco glory and the Canadian hotel giant Fairmont was brought in to manage it.

One morning in 2009 I arrived there in the company of an international posse of hard-drinking journalists. We had been brought in overnight to see the beauty of the restored Cathay/Peace Hotel but one of our number had discovered a bottle of absinthe on the flight and no one was in a good frame of mind. We probably looked just like the kind of decadent Eurotrash that Isherwood and Mr Yang Meng Liang recalled from 1930s Shanghai.

In the days that followed I learned a lot about the Peace Hotel and how it had been built as Sassoon House, the first skyscraper in the Far East. Its ground floor had been given over to banks and shops with offices above. The fourth through to ninth floors once housed the Cathay Hotel and the top floor, originally Sassoon’s own penthouse apartment, was now the hotel’s Sassoon Suite. What I did not discover was where GBS sat and slept and recharged his formidable batteries. At the time he was writing his plays The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles and The Six of Calais.

Shaw’s visit had a surprisingly large impact on China. Today the study of his works continues in Chinese universities in the way that it certainly doesn’t in Britain. At Fudan University there is an annual Shaw essay competition.

Although evidence of the man eluded me in Shanghai, I did learn a great deal about Sir Victor’s hotel with its marble foyers and Lalique chandeliers, and it was easy to imagine GBS enjoying himself at the old Cathay Hotel. Shaw was, after all, one of those Fabian socialists who believed everyone – rather than no one – should be able to drink champagne.

THE ORIENTAL HOTEL, BANGKOK – W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM (1874–1965)

The Oriental Hotel in Bangkok was originally just a few rooms and a lot of verandas on the banks of the busy Chao Phraya River. It was built by a consortium of Danish sea captains responding to the need for European sailors to have somewhere to stay, now that the Kingdom of Siam was opening up to trade. The establishment of a ‘River Wing’ in 1877 is generally held to be the date when the hotel became the institution we know today.

Many itinerant writers stayed in the Oriental’s River Wing in its early days, including Joseph Conrad, Somerset Maugham and Noël Coward (who, like Hemingway, homed in on all the best hotels). Maugham recalled that on one occasion he was almost ejected from his room at the Oriental because the manager thought he was about to die of malaria. That story went into his semi-fictional Far East travelogue The Gentleman in the Parlour, published in 1930.

You have to look for the old River Wing if you visit today. In 1976 the Oriental built a new multi-storey block which was cleverly angled so that every room looked down the Chao Phraya. They named this block the River Wing, while the old part of the hotel was renamed the Writers’ Wing, with a tea room on the ground floor and suites in honour of its most celebrated writers on the first. I always wanted to stay in one of these, but the closest I got on my two journeys through Thailand was being shown round by the management.

The Somerset Maugham Suite wasn’t necessarily where Maugham stayed in 1923 – the year of his malaria – but it might have been, and in any case it had a similar layout. There was a very large mirror, a low 1920s dressing table and a double bed with a mosquito net draped on a frame over it.

A photo taken in the 1920s looks similar except there were two single beds, which would have been used by Maugham and Frederick Gerald Haxton, his American secretary and long-term lover. In his travel stories Maugham invariably depicts himself as the lone wanderer, but in fact, just as Hemingway always travelled with a wife (who was usually written out of his rogue-male narratives), so Maugham took most of his journeys with the gregarious, ebullient Haxton, who chatted to all the locals so that the shy, insular Maugham would have something to write about.

When I peeked into the Maugham Suite I could see the room he described in Chapter 31 of The Gentleman in the Parlour: ‘My room faced the river. It was dark, one of a long line with a veranda on each side of it, the breeze blew through but it was stifling.’ Maugham also disliked the dining room at the Oriental, where guests were ‘waited on by silent Chinese boys’, and the ‘insipid Eastern food’ sickened him. He found the heat overwhelming and soon fell ill, his temperature reaching 105. Having trained as a doctor, he knew immediately it was malaria.

One day, lying feverish in his room, Maugham overheard Madame Maire, the manageress of the Oriental telling the local doctor:

‘I can’t have him die here, you know. You must take him to hospital.’

The doctor suggested they gave it a day or two.

‘Well don’t leave it too long!’

In The Gentleman in the Parlour, Maugham recovers after a few days, ‘and because I had nothing to do except look at the river and enjoy the weakness that held me blissfully to my chair I invented a fairy story’.

That story is told in Chapter 32 of his travelogue. However, Paul Theroux has proved that the story, ‘Princess September’, had been written before Maugham and Haxton set off on their journey from Europe. (We expect writers to be good at their craft and we like them to be inspired by their surroundings, but we can’t expect them to be honest as well.)

Like Maugham, I have spent many hours looking at the Chao Phraya River while staying at the Oriental Hotel. Actually I have only ever stayed at the Mandarin Oriental because in 1985 it merged with the Mandarin in Hong Kong to become one of the flagships of a new hotel company.

My rooms have always been in the modern River Wing where there are suites dedicated to writers who visited later – Wilbur Smith, John Le Carré, and Barbara Cartland.

But I always hoped that one day I’d stay in one of the suites in the Writers’ Wing and recapture the view that had inspired Maugham. The Chao Phraya is an ever-changing urban theatre, like the Bosphorus at Istanbul or the Grand Canal in Venice. I particularly loved the hotel’s teakwood shuttle boats that ferry guests to dinner on the far shore.

Sadly it never happened. When I returned in 2016, en route to Cambodia, I was sorry to hear the writer suites had been swept away in a refurbishment to create a new Royal Suite on the first floor of the Writers’ Wing. Downstairs, however, new lounges have been created to preserve the names of Conrad, Coward and Maugham as well as James Michener and the Thai writer, Khun Ankana. The large ornate mirror that hitherto dominated Maugham’s suite is now the focal point in a lounge, full of white wicker armchairs, named after him.

A Writers’ Wall has also been created in what is now called The Writers’ Lounge, on which is displayed a rotating collection of framed photos donated by the many scribblers to have stayed at the Oriental. I was mollified to see my own picture up there. How long it remained after I checked out I’ve no idea, but I certainly appreciated the gesture.

HOTEL CONTINENTAL, SAIGON – GRAHAM GREENE (1904–91)

The Hotel Continental in Saigon sits opposite a very Parisian-looking opera house. Both face what used to be called Place Garnier but is now Lam Son Square in the renamed Ho Chi Minh City. When you come to Vietnam you get used to most things not being called what they once were, but I’m glad the famous Hotel Continental is unchanged. That said, I wouldn’t have minded if the levels of service or comfort had improved since the 1950s, but you can’t have everything.

On checking in one typically humid day in the summer of 2010, I waited and sweltered while a handwritten account was laboriously taken of my credit card number. I was then left to carry my own luggage to the third floor where I found a wide internal veranda running around the landing. A housekeeper clad in a boiler suit got up slowly from his desk, led me to my room and opened the door for me. He then looked expectantly at me until I tipped him. According to my guidebook, tipping was an alien concept to the Vietnamese but this man had mastered the basics admirably.

My room was spacious but devoid of decoration. It held a desk, two large single beds and two huge carved rocking chairs and that, apart from an arthritic fan in the ceiling, was that. I opened the French windows on to my tiny balcony and they squeaked and juddered. The roar of motor scooters down below filled the room. When I looked out along the hotel’s facade I found my window was next to the faded H of the sign ‘Grand Hotel Continental’. The Continental may no longer claim to be grand but if you’ve read any Graham Greene it is wonderfully evocative of his shabby, compromised world.

The hotel opened in 1886. André Malraux stayed here in the 1920s when he was starting his anti-colonial newspaper Indochine. The legendary US reporter and anchorman Walter Cronkite stayed here too while reporting on what is known in Vietnam as ‘The American War.’ But my reason for coming to the Continental was to write an article for CNN about Graham Greene, who in 1952 holed up here to start a novel about the genesis of that disastrous conflict.

The Quiet American took him over two years to complete and was published in 1955. Greene already knew Vietnam well, having worked as a war correspondent in Indo-China for both The Times and Le Figaro. The Grand Hotel Continental features heavily in his book and also in its subsequent film adaptations. In Greene’s day the hotel was owned by Mathieu Francini, a Corsican gangster. Now it belongs to the state, like much else in Vietnam. In the 1950s it was distinctly louche. It still is. My stay there was by turns atmospheric, grim, fascinating and hilarious.

After a much-needed shower I lay down to rest on one of the hard wooden beds. On the bedside table I found a list of 25 charges intended to deter visitors from pilfering. These ranged from 20,000 Vietnamese Dong ($1) for a coffee spoon to 3,500,000 Dong ($1,600) if you improbably walked off with one of those massive rocking chairs. Carved Continental coat hangers came at a punitive $15 each. I got the impression that this hotel has been swamped by souvenir hunters in the past.

The other details were more appealing, however. A brass letterbox was cut into my door and anything posted through it fell into a small cage. My handwritten breakfast voucher was dropped in later that afternoon.

Breakfast itself turned out to be buffet-style, a delicious mix of Western and Vietnamese fare in the courtyard downstairs in the shade of frangipani trees. Birds dive-bombed the tables for tidbits. My fellow guests were about as international as you could get, with a fair smattering of Europeans and Australians backpacking their way through South-east Asia. The only part of the hotel that disappointed was the bar, which would have been more gracious if it were housed off the courtyard. Instead I found it hidden up on the first floor overlooking the courtyard (hence its nickname ‘The Continental Shelf’ among war correspondents, who claimed they were safe up there from any grenades tossed into the hotel).

Today it’s known as the Starrynite Bar, its logo a mini-skirted Vietnamese maiden playing billiards. Not entirely clued up on modern marketing techniques, the bar proudly proclaims ‘Buy One Beer, Get One Beer’, which struck me as the least you can reasonably expect when handing over your Dong.

But at a time when hotels around the world are increasingly coming to resemble each other, as they compete over ever-greater levels of pampering and try to anticipate your every wish, it’s rather wonderful that the Continental has not moved with the times. The Continental really could not give a rat’s arse about your every wish.

That afternoon I decided to follow the route that Greene’s shabby journalist, Thomas Fowler, takes in Chapter 2 of The Quiet American. I turned right out of the Continental up Rue Catinat (now Dong Khoi) as far as the neo-Gothic cathedral of Notre-Dame. Just across the road from the cathedral is the Central Post Office, built the year the Continental opened and resembling a cavernous railway station concourse from the days of steam. Finally I walked as far as the Rex Hotel, which is still here too, as it was in Greene’s day, and the Chinese market full of over-eager traders. With its excitable merchants and omnipresent motor scooters, this is a very noisy city indeed but still the landscape of The Quiet American.

When I returned to Lam Son Square, I realised I was close to where Greene’s fictional ‘Third Force’ operatives detonated a bomb outside the opera house in both the novel and the two films that have been made from it. So I quickened my pace and returned to the bar of the Continental of Greene’s novel for a gin and tonic. Here you may only get one beer when you pay for one beer, but it’s always been safe from explosions, fictional or otherwise. I found that oddly comforting.