MONK’S HOUSE, RODMELL, EAST SUSSEX – VIRGINIA WOOLF (1882–1941)

And in the end I came to Monk’s House, just down the River Ouse from Lewes in Sussex.

Monk’s House was originally a row of three artisans’ cottages next to a forge. In 1919 Virginia Woolf, emotionally fragile and still to find her voice as a novelist, bought a house in Lewes with her husband Leonard. The couple were looking for a country retreat from London and they bought the property blind. When they discovered it had no garden, Virginia quickly found Monk’s House, which, though primitive in terms of sanitation, heating, water and just about everything else a middle-class London couple might expect from their second home, did have three-quarters of an acre of garden. The Woolfs bought it at auction for £700 and sold their Lewes property for a profit. Never let it be said that great writers have to be otherworldly.

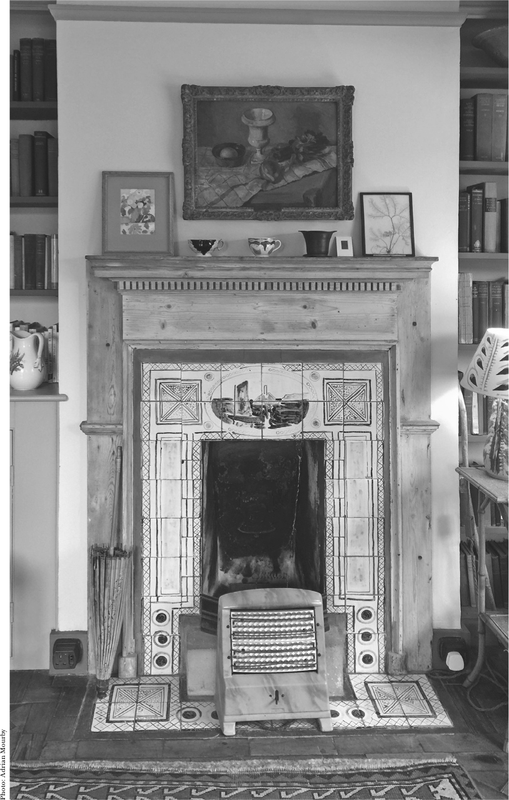

The old white clapboard house at the bottom of a narrow lane needed a lot of work. Internal walls were removed downstairs to create a sitting room (soon painted an arresting green) and a dining room and a kitchen were fashioned. Upstairs there were bedrooms and a further sitting room. Two lavatories were installed, both named after Vita Sackville-West (an odd tribute to one’s former lover), and ten years later, after the success of Mrs Dalloway, the couple added an extension for Virginia, with a ‘room of one’s own’ for writing, accessed from the garden and with her own bedroom above. Of course I had to come here and see the room that Virginia built.

‘This will be our address for ever and ever,’ she declared and indeed the couple were happy, secluding themselves away from London to write and garden. They also entertained the likes of Lytton Strachey, E.M. Forster, T.S. Eliot and John Maynard Keynes with his improbable ballerina wife. Yet it was from this house that Virginia Woolf walked down to the River Ouse to drown herself in March 1941. In one of two suicide letters to Leonard she wrote: ‘Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer. I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.’

I arrived at Monk’s House one very stormy summer’s day, having travelled from Sissinghurst through bursts of sunshine and rain. The whole 90-minute drive between Vita and Virginia’s writing rooms had been delightful. It’s rare, even in England, for two beautiful places to be linked by nothing but unbroken countryside, well-designed houses and pretty villages. I drove straight through Lewes and on to Rodmell, past the Anne of Cleves house where Henry VIII’s fourth queen never lived. (In 1541 the house was given to the former Queen Anne as part of her annulment settlement from the king but she just used it for income.)

Monk’s House, by contrast, is much more deserving of its famous association. All the furniture on the ground floor belonged to Virginia and Leonard, and everywhere there are paintings by Vanessa Bell (Virginia’s sister). In Virginia’s writing room there are the editions of the Arden Shakespeare that Virginia covered with coloured paper while trying to distract herself from a crippling headache. Each has a label on its spine in the author’s spidery handwriting. There was a custodian on hand to make sure I didn’t touch, but, as I peered through my glasses at them, I could experience being within inches of marks made by Virginia Woolf’s pen.

Monk’s House is very popular with tourists, who can access its ground floors most afternoons. Unusually I’d been able to arrange to stay for the night because a room above the Woolfs’ garage (formerly the local forge) has been turned into a self-catering flat by the National Trust who now own the house. Best of all, the room of one’s own that Virginia built for writing in was only about ten feet away from my window as I sat catching up on emails and worrying about the roof above me, which had developed a leak that day.

It’s a pretty refuge and is often taken by writers. There’s a double bed, a galley kitchen and bathroom, and not much else unless you count a pile of Virginia’s novels by the bedside. But the great joy of staying here is that after 5pm when Monk’s House closes, you get the gardens to yourself. I waited until storm clouds passed overhead and then stole out as the birds kicked up a noisy evening chorus. The garden is divided up into ‘rooms’ with low walls and brick paving marking out the different sections. Leonard, who remained a keen gardener for the 28 years of his widowerhood, left the place looking wonderful.

The ashes of Leonard and Virginia are buried in a small walled section of the garden. Two elm trees had stood here which the Woolfs had named Leonard and Virginia. Her ashes were buried close to her tree (sadly it’s blown down since, and twin busts of the couple now mark the spot). I’m glad to say that ‘Leonard’ has survived.

Beyond this memorial, an open lawn leads towards the church. Before you get to it, however, there is a wooden summer house where Virginia worked. Despite having built a room of her own at the far end of the house in 1929 – the year that she published her seminal essay A Room of One’s Own – Virginia found she worked better away from hers, in a shed at the far end of the garden.

I peeped inside and saw her typewriter and spectacles lying on a suitably austere desk. Here she worked on her last books: The Waves (1931), The Common Reader (1932), Flush (1933), her one comic novel, The Years (1937), Three Guineas (1938), a sequel to A Room of One’s Own, and Roger Fry (1940), a biography of her friend, the art critic and painter. The poor reception that this book received exacerbated her depression and thoughts of suicide. Meanwhile, the extra room she built on to Monk’s House became her bedroom. Servants would find the floor around her electric fire littered with screwed-up pieces of paper in the morning.

Just beyond Virginia’s shed is the garden gate where some time after 11am on Friday 28 March 1941 she left Monk’s House and headed for the river, threw away the stick with which she walked and put a heavy stone in her coat pocket. Her body was not found for another three weeks. It had floated hardly any distance and come to rest against the supports of a bridge.

I hope it doesn’t sound ghoulish to say that where a writer dies often tells us far more than where he or she was born. Virginia Woolf has been retrospectively diagnosed with bipolar disorder. She was also depressed that her recent works were not well received and that her London house in Tavistock Square had been bombed out during the Blitz.

But Monk’s House does not feel like a sad place at all. In this shambling, rambling, bohemian place with its glorious English garden and writing-room-turned-bedroom it is clear, as she herself put it, that no two people could have been happier.