In Virginia, site of the 1831 Nat Turner slave revolt that so frightened nineteenth-century southern whites and for more than a century festered in the white establishment’s public memory, the NAACP filed more civil rights lawsuits than any other state. On the one hand, it was the state represented by Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr., author of the “Southern Manifesto” and leader of the Massive Resistance movement; on the other, it also experienced a lawsuit that desegregated interstate bus travel in 1946, hosted one of the five school desegregation lawsuits that was combined into the case that led to the 1954 Brown decision, and witnessed the famous 1967 Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court decision that overturned state laws banning interracial marriage. All these events received considerably more public and historical attention than the desegregation of Virginia’s public libraries. Two such cases, however, are especially notable; both occurred in the wake of the Greensboro sit-ins.

During the Civil War, Petersburg had witnessed the final collapse of Robert E. Lee’s army. In subsequent decades, it developed into a railroad town that by the mid-twentieth century transferred much of the tobacco and peanuts grown in that part of the state to external markets. When Clara J. McKenney donated her antebellum mansion home of high ceilings and marble fireplaces to the City of Petersburg for a public library in 1923 as a memorial to her husband, she stipulated that while whites would have exclusive use of upper floors of the building, “the basement be kept and maintained for the exclusive use of Negroes”—an “enlightened stipulation” for the 1920s South steeped in Jim Crow practices. At the time, Petersburg was 40 percent black. Should the city fail to conform to this and other requirements, the property would revert back to her or her heirs.

The first floor and the basement had equal space when the city gladly accepted the donation. By the time McKenney died in 1942, however, the city had built two additions costing $25,000 to the first floor; both served only whites. Dion Diamond later remembered approaching the twenty-four-room Petersburg Public Library as a black seven-year-old in 1949: “It was easy to walk through the gate and up the steps,” he recalled, “but the lady at the door looked at me and said, ‘Little boy, you’re supposed to go to the side entrance, and down in the basement.’” The basement library, the black weekly Richmond Afro-American noted, was a “three-room affair with 14 seats and outmoded lighting fixtures.” Perhaps this humiliation played a role in Diamond’s later activism as a Freedom Rider, in which he suffered more than thirty arrests. Although young Diamond could request any book in the library, identifying any that were outside the basement was impossible because the library’s only public card catalog was upstairs.1

But in late June 1959, Rev. Wyatt T. Walker, pastor at the Gillfield Baptist Church, state president of the Congress of Racial Equality, and president of the local NAACP chapter, walked into the Petersburg Public Library front door to request Douglas Southall Freeman’s highly laudatory biography of Robert E. Lee.2 Several reporters he had previously tipped off were there to cover what happened; Walker was refused service and told to go to the basement library. At the time, Petersburg—recently declared an “All American City” by a national magazine—employed no blacks in its police or fire departments, in city hall, or in its public library. Days later, the NAACP petitioned the city council to desegregate the facility. When city officials told the local press that “all books and research material in the city library are available to Negro patrons, for whom there are reading rooms with a special entrance,” the chapter petitioned the council to close that entrance and instead substitute “a common entrance for all.” On June 30, Virginia Claiborne—daughter of Clara McKenney—wrote Petersburg’s mayor to endorse the petition. “The present branch facilities . . . represented human dignity in 1923. The same is not true in 1959,” she wrote. Neither she nor the mayor made her letter public.3

On February 27, 1960, just four days after a series of unsuccessful sit-ins at Petersburg’s Kresge lunch counters, young blacks in groups of 3 to 6 began entering the Petersburg Public Library shortly before noon. Within minutes, 140 blacks, mostly high school and college students with “a sprinkling of adults who were counselors for the students,” the white Petersburg Progress-Index reported, occupied all the tables and wandered about the aisles. One approached the circulation desk and requested the Freeman biography of Robert E. Lee. When told he could get it downstairs in the “colored” library, “he shook his head and walked off.” Others who requested books were given the same response. To a reporter, Wyatt Walker identified the activity as a “student-organized movement. They came to us.” “It is significant that the library was attacked and not the lunch counters,” he told the Richmond Afro-American later, “for this means that we are opposed to segregation in any form that it takes.”

In response to their presence, the city manager immediately closed the library until the council could discuss the matter the following week. At a meeting thereafter, students vowed to continue their protests not only at the library but also at lunch counters and schools. “Regrettable,” a Progress-Index editorial labeled the demonstration. “These sit-down demonstrations usually are described as orderly. . . . However, the fact that the demonstrators have been drilled in quiet and uncommunicative behavior does not obscure the larger fact that there is something essentially disorderly about these large-scale affairs which appear to have been so carefully planned.” The city manager immediately began hinting that Petersburg might have to close the library permanently if forced to integrate because such a ruling would violate stipulations in Clara McKenney’s gift.4

At a March 1 meeting attended by seventy citizens—including about fifty of the students who had protested at the library three days earlier—the city council heard one of the protestors, C. J. Malloy, a student at the historically black Virginia State College, read a group statement that accompanied their petition to desegregate the library. “Segregation as a part of the fabric of American life is dead,” he said. “We stand on the threshold of America becoming her ideal.” Council members listened politely, quickly dismissed the petition, then unanimously passed an “anti-trespass” ordinance before announcing a decision to reopen the library on a segregated basis on March 3. Asked by a Richmond Times Dispatch reporter what he intended to do, Wyatt Walker responded: “This will in no way intimidate or thwart our efforts for desegregated facilities. If it will be necessary to go to jail, we will go to jail.” He noted these kinds of demonstrations had assumed a “pattern across the South” and suggested the possibility of a federal lawsuit. “This reduces the city of Petersburg to a police state,” said another NAACP spokesman. The Progress-Index saw council action differently. “Law and order will be served,” it declared in an editorial. The newspaper echoed the city’s position that it was bound by the terms of McKenney’s deed. On March 3 the library opened again, without incident.5

Four days later, however, seventeen blacks entered the white sections of the library, including six Virginia State College students, two high school students, ministers Wyatt Walker and R. G. Williams, and Walker’s wife, two children, and the child of another demonstrator. Mrs. Walker and her children immediately occupied tables in the white children’s room. Others took seats in three reading rooms; Walker again asked a librarian for Freeman’s biography of Robert E. Lee, by now a running joke among all protesters. The city manager, who had been tipped off about the sit-ins, asked all but Mrs. Walker and the children to leave and advised them they were subject to arrest if they did not. They responded that they knew about the ordinance and were prepared to go to jail if necessary. After they sat quietly awaiting warrants, police arrested eleven demonstrators and took them to the police station. Rather than post bond, five chose jail, where for two nights they slept on the floor. “We are staying in jail to dramatize the full implication of what this hastily enacted city ordinance means” to Petersburg’s citizens, said Walker. “We sincerely believe this ordinance violates the guarantees of the bill of rights, the right of assembly and the right of protest.” Said one of the students not arrested, “From the moment the City Council passed the anti-trespass ordinance we were committed to a position of civil disobedience.” From jail the five inmates issued a statement: “In the light of our democratic principles and current social changes we feel that the city ordinance passed by council affecting ‘trespass’ laws is untenable, unchristian, and unconstitutional. It would be both timely and wise for our city council to reconsider the petition to integrate the public library.”6

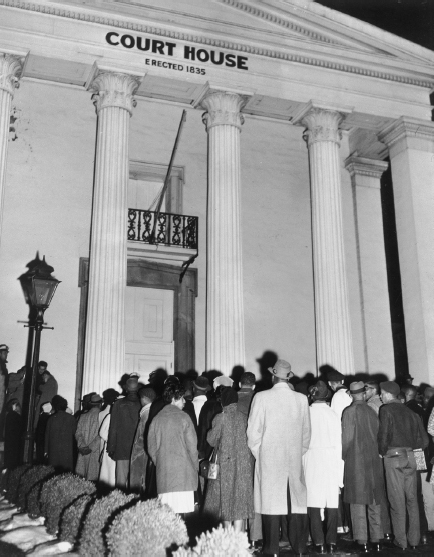

On the courthouse steps the next evening, in twenty-six-degree temperatures, two hundred Petersburg blacks protested the arrest of the demonstrators. Because officials had turned off floodlights that normally illuminated this public building, one protest leader read by flashlight: “We will be jailed by the thousands and while there make plans for full integration and equal rights behind prison walls.” Said another, “It is with regret that a city with a population of approximately 40,000 people cannot afford to own fully and operate democratically a [public] library for all of its citizens without suffering the penalty of being jailed as criminals.” Scores of whites stood across the street, many booing, some heckling.7 The next day the five arrested were freed on bond, just in time to attend a mass rally at Zion Baptist Church; fourteen hundred attended to protest the anti-trespassing ordinance and segregated practices at their public library. “We will rid the City of Petersburg of every vestige of discrimination and segregation,” said one rally leader. Martin Luther King Jr. sent a telegram of support. After the rally, lawyers representing those arrested said they would file a federal lawsuit requiring Petersburg to desegregate its public library.8

At trial on March 14, as six hundred black supporters “filled the steps leading to the courtroom” and sang hymns and prayed, sixty filed into the courtroom, where they were first directed to take seats on one side, then, when all those seats were full, were herded into three back rows on the other side. The defendants declined to take the stand. City officials did testify, however, including the police chief, who admitted the defendants had been arrested “because they are of the colored race and the city had consigned them the use of a side door.” When the judge rendered his decision, he fined Wyatt Walker and R. G. Williams $100 and sentenced them to thirty days in jail for violating the anti-trespassing law. One Virginia State College student was fined $50 and sentenced to ten days in jail, and eight other defendants were fined $50 each. All were released on bond pending appeals.9

Immediately after they were sentenced, nearly two hundred supporters formed a thirty-car motorcade to Richmond to file a petition on behalf of the eleven convicted to end segregation at the Petersburg Public Library, which, their petition said, constitutes a “nauseating practice” and was “humiliating, embarrassing, and grossly unfair . . . and unconstitutional.” After filing the petition, supporters joined a picket line protesting the discriminatory practices of a downtown Richmond department store.10 In the meantime, Petersburg’s city manager vowed to keep the library open on a segregated basis.

City action surrounding the public library functioned as a catalyst for other Petersburg civil rights activities. Milton A. Reid, a black Baptist preacher, announced his candidacy for city council, an all-white bastion of local power preserved in large part by making it difficult for blacks to vote. A new black organization, the Petersburg Improvement Association (PIA), promised increased numbers of demonstrations at chain-store lunch counters, swimming pools, and playgrounds. The PIA declared a moratorium on the library, however. As “a matter of litigation, there is nothing more we can do about it,” Walker said. “We are not going to harass them, as the city manager expressed it. All we did was go there to read.” Eight hundred miles away, forty-one African Americans, including five newspaper reporters, were arrested that day at Memphis’s public library.11

Petersburg blacks braced for reaction. When a Washington Post–Times Herald correspondent visited the city that week, she reported that white community leaders actually thought that “the Negroes were satisfied with the patterns of segregation that have evolved since the Civil War,” that demonstrations at the library “have been stirred up by outside agitators and will subside,” and because white town officials “do not recognize the Negroes as leaders” and were “not taking the sitdowns as a serious protest,” they felt no need to establish channels of communication with the local black community. And because of the court case filed against the library, she observed, “an uneasy truce now prevails in Petersburg.”12 That week the PIA sent two letters to city officials asking for meetings to discuss desegregation issues; officials ignored both. On March 21, someone threw a bottle containing an obscene note directed at Wyatt Walker’s wife and signed “KKK” at her front window while she and her four children were home alone. It broke but did not shatter the window. “Friends stood guard at the Walker home the remainder of the night”; the next day the family requested and received police protection.13

On March 29, Virginia Claiborne, McKenney’s daughter, wrote Petersburg’s mayor a second letter calling for desegregation of the public library her mother had donated to the city. “In spite of my distaste for some of the tactics used in the present matter,” she wrote to the mayor, “I wish to back Petersburg’s colored citizens in their move for desegregation of the library, now that they have taken the initiative.” On April 4, she made her position public, released her June 30, 1959, letter to the press, and criticized the mayor for not having publicized it a year earlier. Because their relationship with Petersburg blacks in the first decades of the twentieth century was “unique, believing as they did that to be treated with dignity breeds dignity,” because “the original and amended deeds of the gift represent a positive, not a negative, affirmation on the only terms then tenable or even imagined,” her parents, she told the Richmond Afro-American, would stand with her in 1960 were they still alive. When the Washington Post–Times Herald asked how this would affect the city’s response to the federal suit, Petersburg’s city manager replied that the “the deed will be invoked as the city’s defense in court.” The next day—the same day as local city council elections in which Reverend Reid lost but placed fourth, with the most votes ever garnered by a black candidate—the city asked the court to dismiss the suit because Virginia statutes governing segregation practices had not been found unconstitutional by the state supreme court of appeals.14

Angry that it had received no response to two letters to white city officials inviting cooperation, on April 13 the PIA announced a citywide campaign to desegregate lunch counters, schools, and all public facilities. Its first targets would be six segregated lunch counters; it also planned two additional suits aimed at desegregating schools and courtrooms. “The lid is off,” said Wyatt Walker. “We go to court to fight segregation and we have to sit in segregated seats.” Days later, a Virginia state judge ruled Petersburg’s anti-trespassing law constitutional. “It has taken America almost one hundred and eighty four years to build our great nation,” argued one citizen in the Progress-Index’s “People’s Forum,” “and there is no use in letting a bunch of overheated Negroes from way up north try to take it over.”15

As all this whirled around the city of Petersburg, on May 20 federal district judge Albert V. Bryan held a hearing in Richmond on the public library case. Virginia Claiborne testified that she welcomed integration and would not ask for the building to be returned to her mother’s estate. The basement room that served blacks was “dingy, dirty, and badly lighted,” testified the Reverends R. G. Williams and Wyatt Walker. But the library was “fully available” to blacks, Petersburg lawyers responded. “So long as the library is available to both races, we feel the practice of segregation is valid.” No, plaintiffs’ attorneys argued, the library was not available to both races. Blacks had no access to the card catalog—and thus did not know what materials the library held—and modern reference books and current periodicals were not available in the basement. Toward the end of the hearing, city officials informed Bryan that if ordered to integrate, they would be forced to close the public library. The city would then bring suit to adjudicate the terms of the deed that had conveyed property to the city. But how would that help Petersburg citizens? the plaintiffs asked rhetorically. “I think it would be a detriment to whites and Negroes if the library would be closed,” responded Williams. That the national media had interest in the hearing was obvious when Judge Bryan ordered a United States marshal to confiscate the film of a Life magazine photographer who had taken a photo through a window in the courtroom door.16

At Virginia Claiborne’s prompting, Louis Brownlow, Petersburg city manager at the time her mother gave the building for a library in 1923, wrote a letter made public in early June. “There is not the slightest doubt in my mind that the one condition which your mother insisted upon in the name of your father was that this library should be open to all the citizens of Petersburg, and especially to the Negro citizens,” Brownlow wrote. “Mr. McKenney, in his lifetime, took a strong position with respect to liberal and dignified treatment of the Negro citizens of the community.”17 On June 21 the city council reiterated that it was only trying to carry out the terms of the original deed. The Progress-Index sympathized with their plight. “Petersburg is receiving the full benefit of advice and lectures from outside sources—newspapers, former officials, and what have you,” it editorialized, yet “nothing could be more specific than the provision of the deed calling for segregated use of the facility, whatever the intent may have been and however the intent may be interpreted in this year of grace.”18

When three Virginia State College students—all among the eleven arrested on March 11—again sought service on the first floor of the public library on July 6, the city manager decided to close it down indefinitely pending a court decision regarding the validity of Clara McKenney’s deed. Ironically, officials closed the library three days before hiring a new librarian to succeed the retiring librarian named in the federal lawsuit. “In the meantime,” the Progress-Index reported, “members of the library staff continue at their posts behind an entrance door which bears the sign: ‘Closed until Further Notice.’”19

On July 21, a Virginia state judge dismissed charges against the remaining youths arrested on March 7 for violating Petersburg’s anti-trespassing law. But protests continued at other public facilities. On July 30 fifteen black students were arrested for trespassing in the white section of the Trailways Bus Terminal restaurant. The next day, three hundred gathered at the courthouse for their hearing. Additional arrests took place as students continued to sit at terminal lunch counters in subsequent days. “Fill the jails,” demonstrators shouted as they were led to police cars.20 On October 6, Judge Bryan announced he would decline to rule on the Petersburg public library case. Because the library was closed indefinitely, he reasoned, issues listed in the complaint no longer existed.21

But behind the scenes, matters moved quickly. In what one observer called “a surprise move,” on November 4 city councilman William Grossman offered a resolution to reopen the Petersburg Public Library. “We may lose the library if we continue to keep it closed,” he said. The city manager cited court cases that dismissed anti-trespassing charges against demonstrators and indicated he could no longer enforce the ordinance. That council members were prepared for the resolution was obvious when they approved it unanimously. Three days later, the new librarian opened the front doors of the library, which had been closed for four months. No Petersburg blacks entered that first day. “The branch library in the basement will continue operation as long as authorities feel there is need of it,” the Progress-Index reported delicately. “Negro patrons who come into the portion of the library formerly reserved for white persons will be served.” When the library opened that day, it became the ninth Petersburg public facility to desegregate since the February 26 Kresge lunch counter demonstrations. “Another victory for the sitdowners,” crowed the Richmond Afro-American.22

That Petersburg was shifting attitudes toward integrated civic institutions was obvious from subsequent events that elsewhere brought bloodshed. When Freedom Riders came through Petersburg on May 5 aboard a Trailways bus at the beginning of their historic journey that witnessed violence in Alabama days later, they met no resistance at the terminal. Instead, they were greeted by locals, many of whom had worked through the Petersburg Improvement Association the previous August to desegregate the facility and had also participated in the events that forced the integration of the Petersburg Public Library in November. Taken together, all these successful efforts—most of which were spearheaded by local black high school and college students—had the effect of softening support for Jim Crow practices in Petersburg and reassuring Freedom Ride organizers that at least in Petersburg, as one historian argues, their “successful testing of local facilities was almost a foregone conclusion.”23

Less than 150 miles southwest of Petersburg, black seventeen-year-old Robert A. Williams of Danville, Virginia, learned about the 1960 Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins the day after they occurred. He immediately approached his high school friends about how to challenge Danville’s segregated facilities. “Based on dinner conversations with my father [NAACP attorney Jerry Williams], and his conversations with other friends about what we could accomplish through the law,” he later recalled, “I was able to convince the other students and our adviser that the first attack we should have was against the public parks and the public library.”

Williams knew enough about the law to recognize it would be easier to attack publicly funded institutions than privately owned establishments such as restaurants and hotels. He had also followed news about the sit-in at the Petersburg Public Library in March, in which eleven black youths had been arrested for trespassing. In the spring of 1960, his group met with Chalmers Mebane, a black World War II veteran who, like them, wanted to desegregate local public accommodations. “We planned what we were going to do, the routes we were going to take, and the objects that we were going to fight against in terms of the public park and the public library.” They also met with local NAACP officials to discuss the “legal aspects of the sit-in demonstrations and what we could use them for and what type of support we could garner from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.”24

Danville’s public library stood as a testament to the Old South. It was housed in a mansion declared the “Last Confederate Capitol” by a prominent bronze sign on its front lawn. Built in 1859 by Confederacy quartermaster William T. Sutherlin, it served as the executive mansion for Confederacy president Jefferson Davis, who fled there after Robert E. Lee recommended the evacuation of Richmond. It was there that Davis held his last cabinet meeting before the war ended. Danville’s black residents did not share whites’ pride in the mansion or their interpretation of its past. “The city had the nerve to take pride in the fact that it was here,” writes Danville native and civil rights activist Evans D. Hopkins, that Davis “had hidden out for seven days before Robert E. Lee’s surrender, after having been run out of Richmond by the Union Army.”25

For generations the library served only whites, although in the early 1930s the white librarian hired Mrs. Frankie H. Jones, a black assistant, who, ironically, assumed responsibilities when the librarian left. “Because Negroes requested it,” a Danville mayor recalled thirty years later, the city opened a branch in the black high school shortly thereafter and transferred Jones there. In 1950 the collection moved to two small rooms in a separate building two blocks away from the white library. Although the new William F. Grastey Branch (named after a revered twentieth-century black Danville educator) “mainly had books discarded from the segregated main library,” Evans Hopkins later recalled having spent hours there discovering literature and new worlds, and admiring the beauty of words.26

On Saturday, April 2, 1960—the ninety-fifth anniversary of Davis’s retreat from Richmond to Danville, two months after the Greensboro lunch counter sit-in, and five weeks after the Petersburg library sit-in—Williams and fifteen friends from the Loyal Baptist Church met at Ballou Park. The police quickly arrived, recorded the students’ names and addresses, and closed the park. Williams and his group then walked to Main Street and into the all-white Danville Confederate Memorial Library. The librarian refused to let them take out books, telling them the library was closed. They sat down briefly, then left. “We felt on that day, very, very triumphant—that we had accomplished what we wanted—that was that if we could not use the park and the library, then they would be closed to all.”27

“Racial calm in this Last Capital of the Confederacy was broken today as a group of Negroes of high school age entered the public library, bringing its closing two hours ahead of the usual time,” the white Danville Bee reported. In an emergency session the next day, the city council passed an ordinance to limit library usage to existing cardholders because “facilities of the Danville Public Library are overtaxed by the demands of its patrons.” In an editorial the Bee lamented: “The arrival in Danville of the Negro juvenile Gandhi-like revolt ushers in untold future consequences posing a grave problem to orderly government. . . . The conservative people of Danville deplore this rupture of homogeneous relations between the Negro and the white man of this community, because it brings to an end what, for decades, has been a sympathetic and understanding racial coexistence. It has endured ever since Danville citizens in November 1883 drove out the northern carpet-baggers and convinced the colored people that they had been the tools of unscrupulous self-seekers, just as they are today.”28

The following week, black teenagers reappeared in groups of four, and when all requested library cards and library privileges, the librarian told them about the new city ordinance and urged them to visit their own library. “Few of the Negro students who invaded the main library,” the Bee reported, “have ever used any of the library facilities available to them, a check of records disclosed today.” The following Saturday night, April 9, Williams and his neighbors watched as crosses were burned on the front lawn of the Loyal Baptist Church and at the home of its pastor, Rev. Doyle J. Thomas, then president of the NAACP’s Danville branch. On Sunday morning a local newspaper published on the front page the names and addresses of the students who had attempted to use the public park. Later that day, the Loyal Baptist Church hosted a mass meeting attended by 350.

“Burning crosses on front lawns is not going to solve Danville’s present racial complexities,” the Bee wrote, expressing surprise at discovering “a feeling of dissatisfaction among the colored people of Danville”; the newspaper attributed it to “outside agitators and reformers” who “came here to egg on children to mass acts of provocation.” Shortly thereafter, the NAACP voted to file a federal lawsuit to challenge segregation in the public library and other public facilities. Robert Williams’s father agreed to draft a complaint, with the help of Danville attorneys Ruth Harvey and Andrew Muse and Richmond attorney Martin A. Martin.29

On April 11, the city council met in a special session. A group of “25 leading citizens” had met the previous evening, one councilman reported, “and voted unanimously in favor of closing rather than integrating.” In response, the council requested that the mayor appoint a committee to consider the request.30 But not all Danville whites agreed with those leading citizens. On April 19 thirty-one whites met to organize a “Committee for the Public Library” and sign a petition to the mayor to keep the city library open “without interruption.” When asked if the petition meant the group favored integration of the library, its spokesman had “no comment.” Days later, the white petitioners announced they had garnered the signatures of “300 additional leading white citizens.”31 On April 13, however, local NAACP attorneys filed the complaint, asking for an injunction to desegregate not only the public library but all public facilities and accommodations in Danville.32

The case ended up in the court of sixty-two-year-old federal district judge Roby Thompson. At the May 5 hearing, before a packed courtroom of twenty-five whites and nearly one hundred blacks, city manager T. E. Temple testified that because blacks had “on numerous occasions” in the past used the public library without incident, there was no discrimination. Then why was the library closed on April 2? asked NAACP attorney Martin. “To maintain peace and good order,” the city manager responded. “Wasn’t it simply because they were colored?” No, Temple said, “it was the manner . . . mass entrances.” How many tried to enter the library? Martin asked. “10 or 12,” Temple said. That’s a “mass”? Martin asked. Many blacks in the courtroom snickered; some laughed. Why were black students not allowed to enter the library on April 6? Martin asked. Because the ordinance the city council passed two days earlier restricted use to library cardholders. Could Danville citizens use the reading room without a card? Martin asked. Yes, Temple replied. “If Negroes go up there this afternoon, could they use the reading room?” Martin pressed. “Yes,” Temple responded and after a pause added, “If they have a card.” Again, there were snickers from blacks in the crowd. (The city attorney told a Rotary audience weeks later how “exasperated” he was “to hear the snickers and laughter among Negro spectators who filled the courtroom” when he “lost a point.”)

The next witness after Temple was librarian Florence Robertson. On those occasions when black people used the library, she said, “we made no distinction and never had any incidents previously.” Martin then asked if these “occasions” were “special” and involved black workers sent there by white employers. For many yes, she said, but not all. This time the judge interjected to focus the line of questioning. “The only point is this: Is the City of Danville operating a free public library with public funds and denying some citizens use because of race?”33 He then ended the hearing. On the following day Thompson granted the injunction, ordering the city to extend full library privileges to Danville’s black citizens. When the city announced that it planned to appeal, however, he suspended execution of the injunction for ten days to give the city “the right to apply to a higher court.”

The response of Danville’s white establishment to these events showed grave concern. What to do? The Danville Bee suggested an action unique in the history of desegregating public libraries in the South: call an advisory referendum. “The council is at grips with one of the deepest problems within this generation which has confronted city government,” argued the Bee. “It is a problem which in the long look ahead far transcends whether the library shall function or whether it shall not function.”34 The city agreed, and on May 14 a local judge set the date for a five-point referendum for June 14, the same day as council elections were scheduled. Citizens would be asked if they wanted: the entire system closed; facilities closed “if it appears that private facilities will be reasonably available”; the system to be open to all; the city council to work out a “modified plan” to continue to operate the system; or the library closed and books distributed through the bookmobile service.

By calling for an advisory referendum, however, they automatically pushed the issue of closing the library into local election debates. At a forum conducted by the Junior Chamber of Commerce on May 27, for example, four of the six common council candidates vowed to fight integration of the city’s libraries. The other two agreed to abide by the decision of the advisory referendum. The topic also preoccupied other public discourse. On May 30, the Rotary Club heard the city attorney say that “to protect ourselves,” the public needed to be “awakened” to the issue because the library integration suit was yet another example of how “certain rights of the majority race are being trampled.” To prove his case he noted that most of the books in the “colored library” were also in the main library and any book not in the former could be requested from the latter and delivered “within fifteen to thirty minutes. Now, if anyone can tell me what irreparable harm or damages that were going to endure to the detriment of the plaintiffs according to what I just enumerated, I would sure like an explanation.” No one in the audience pointed out to him that without access to a public card catalog Danville’s blacks did not know what was in the main library that their taxes supported.35

On May 16, the same day the council filed a formal notice of appeal of Judge Thompson’s ruling, a steering committee formed to organize a private library foundation and mobilize opposition to integrating the library. The effect of the mobilization effort on the council was obvious. On May 19, council members voted to close the city’s public libraries and its bookmobiles the next day rather than comply with Judge Thompson’s order. As word spread, “there was a rush on the main library . . . by persons desiring books, many of them getting stacks of volumes ranging up to between 15 and 20.” Then, on the evening of May 20, the Danville Public Library system “closed without fanfare.” Library staff members were not affected by the closing, the Bee reassured its readers the same day. On the following day someone tacked a “crudely made sign” on the library’s front door that read, “Congradulations [sic] on this intelligent display of true Americanism.”36

Just two weeks later, a newly formed “Danville Library Foundation” announced it would open a private segregated library to evade the court order. One founder argued: “You cannot appease the NAACP. If we compromise this thing we will have to face it again . . . in some other quarter.” Whites who argued that few blacks would use an integrated library were “appeasers. . . . Let us not be misled by these appeasers—these prophets of compromise. Let us organize to demand our constitutional rights.” “We believe the people would prefer a private library rather than making any concessions to the NAACP,” said another.37 The group planned to move into a fourteen-room mansion across the street from the main library and expected to pay for rent by selling eight thousand annual public subscriptions at $2 per adult and $1 per child.38 It planned on spending $9,500 for books and periodicals. The city attorney advised the group it could not simply transfer the public library books to its private use because they had been purchased in part with taxes from Danville’s black citizens.39

Public opposition began to mount outside Danville. “I, too, feel the old prejudices,” novelist William Faulkner told an audience at the University of Virginia commencement on June 3 but added, “When the white man is driven by the old prejudices to do the things he does, I think the whole black race is laughing at him.” He opposed closing public libraries in Danville and Petersburg: “I think everyone not only should have the right to look at everything printed, they should be compelled by law to do so.”40 The Richmond Times-Dispatch agreed. “Keep Libraries Open,” it titled a June 13 editorial. “We expect to resist massive integration of our schools with all legal and proper means. We also oppose the mixing of races in restaurants, hotels, swimming pools, and so on,” it argued. “But libraries are in a different category. . . . A library is a place where interracial contact is at a minimum, and where students and readers sit quietly and mind their own business.” Virginia public libraries in Arlington, Charlottesville, Fairfax, Harrisonburg, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Richmond, Roanoke, and Winchester had integrated, the newspaper noted, most “without any trouble arising. . . . Do the people of Danville and Petersburg wish to place themselves in a class apart, and to abandon the well nigh universal practice of making the wisdom of the ages freely available to all?”41

On June 8, the Committee for the Public Library mailed a letter to all of Danville’s registered voters. “It is not, as some have said, a question of whether you approve of integration or of segregation, for the matter of the public library should be above this question,” it read. “It is simply a matter of whether or not you want your city to have a library staffed and equipped to perform all essential services . . . that a library is expected to perform, or whether you want to do without these services.” The Danville Library Foundation countered, “In the final analysis it must be the question of whether you approve of integration or segregation,” and if Danville integrated its public library now, it would “give the green light to the NAACP to move further and faster with their plans for total integration. . . . If people vote to close the public library, there nevertheless will be a library available to the white people of Danville.”42

On June 14, Danville residents went to the polls to vote on the referendum. At the time, blacks constituted 33 percent of Danville’s population, though fewer than 10 percent were registered to vote. Of Danville’s total population of 46,253, only 5,942 voted—yet not without incident. When polls opened at 6:00 a.m., members of the “Danville Committee on Negro Affairs,” a local NAACP organization, began handing pink sample ballots to black voters that advocated for desegregating the public library; it also named five council candidates it supported. None of the five had been informed of the committee’s initiative, however, and although all of them denounced the pink ballot, by noon it appeared the effort was backfiring against the NAACP as “supporters of some of those candidates listed on the pink ballot became so incensed at the tactics used that, they said, they decided definitely to vote for closing the library rather than opening it to all as advocated on the ballot,” the Bee reported.43

Not surprisingly, by a margin of nearly two to one (2,829 to 1,598), voters opted to keep the library closed.44 “I surely hope the responsible colored citizens of Danville will take their cue from the results of the referendum on the library and drive the NAACP from their midst,” said one city official. “It is only in that way that the good relations which formerly existed here between the races will be restored.” The Bee celebrated “vox populi.” “The solidarity of Danville in this matter may have caused some acid remarks by the neo-liberals in coalition with the Negro voters,” it wrote in an editorial, “but it has at least reflected the truth that there are still a lot of unreconstructed rebels in Virginia not disposed to accept lightly an invasion of state rights by the federal judiciary, nor the vindictive purpose of alien reformers who hoped by the referendum to trumpet the claim that the onetime seat of the Confederate government had struck its colors.”45

The issue would not die. The city council was split five to four against reopening the public library until a private library was available, so nearly two hundred people met to organize a petition drive for 5,000 signatures of “white citizens” to reopen the library “on an emergency basis.” (One of the organizers teased, “An emergency may last 50 years.”) But on June 24, Danville Library Foundation officers exercised a five-year lease on a site for the private library. “This is a community project,” said Councilman John Carter, who led the effort. “It is one that can and will succeed. Let’s do nothing to interfere with the tasks ahead.” At a city council meeting the next day, a spokesman representing the group to reopen the library presented a petition bearing 3,151 signatures, but even after one council member suggested the possibility of reopening it after removing chairs and tables so blacks and whites would have to stand while using the library, no member changed his mind.46

The idea of a private library was certainly not welcomed by Danville’s black population, but it was obviously not popular with many whites either. Opinions were split, with some concerned about negative national publicity, others about whether the conflict would hurt the local economy by discouraging new industry from moving there. Many of those in favor of keeping the library closed clung to the status quo, arguing that the two races had lived in peaceful harmony until this time and it was only NAACP attorneys who had stirred things up. They insisted the city stand its ground.47

This dissension resulted in several citizen initiatives. One group of thirty-one residents, “the majority in the field of medicine, dentistry, research chemistry and two officials of the Dan River Mills,” a local fabric manufacturer, petitioned the city to reopen the library on an integrated basis. They began meeting at the home of Samuel Newman, “noted humanitarian and champion of democracy,” one library periodical called him, and then opened up negotiations with Danville’s mayor, the city manager, the city council, the city attorney, and the head of the Danville Library Foundation. Most of the meetings also included NAACP attorney Jerry Williams. By this time, it was becoming apparent that the foundation was having difficulty raising sufficient funds.48

When city councilman D. Lurton Arey presented the group’s petition, he proposed that the library be open only on a “vertical plan” that would involve removal of all chairs and tables. Persons of both races would be able to enter the library and apply for specific books. Those books would be delivered to the applicant, who would then exit the library—a “get in, get out” plan. For in-library research the applicant would receive the materials and be assigned a numbered booth in which to study.49 The idea, later termed “vertical integration” (a term segregationists adopted from economics that had nothing to do with race), may have come from a satire penned by American journalist Harry Golden in a 1956 article and reproduced in his 1958 book, Only in America. He noted that blacks and whites seemed to get along fine “so long as they stood near each other in grocery stores, dime stores, and the like,” but “it is only when the Negro ‘sets’ that the fur begins to fly.” He came up with the “Golden Vertical Negro Plan,” in which desks but not seating would be provided for students in public schools.50 Either because someone in Danville had read Golden’s book or because they had reached the same conclusion, the city liked the idea.

While the libraries remained closed, racial tension continued. On September 4, the Ku Klux Klan gathered at a racetrack outside of town, raised the Confederate flag, burned a cross, and listened as imperial wizard J. B. Stoner of Atlanta launched a virulent attack primarily against black Americans but also against Jews, “Judas Iscariot” preachers, Communists, Hollywood, and the U.S. Supreme Court for its integrationist rulings.51

On September 13, nearly four months after the city had closed its libraries, the council voted five to four to reopen them on a “stand-by” integrated basis for a ninety-day trial period. (At least one councilman voted yes because of the negative publicity Danville was receiving; he noted that an industrial plant had decided not to move to Danville in part because of the controversy.) All borrower’s cards would expire October 1, forcing anyone who wanted to use the public library thereafter to reapply. In addition, applicants had to fill out a four-page form calling for two character references and two credit references over which officials promised “rigid scrutiny.” (Similarities with registration forms previously used throughout the South that were deliberately crafted to discourage African Americans from voting were unmistakable.) Finally, all applicants also had to pay a $2.50 application fee. “If all goes well,” the city manager promised, chairs and tables would be reinstalled at a later date.

The vote that shifted the majority to reopening the library belonged to Councilman George Daniels, who agreed to the motion because it specified “stand-up service only.” Nonetheless, he and Councilman James Catlin vowed to close the library again at the council’s next meeting unless the NAACP withdrew its suit. “I’m not willing to vote to open libraries unless the local colored leaders will withdraw the suit,” said Daniels. “Why wouldn’t they?” commented Councilman John Carter, who remained a no vote and had been a central force in the failed effort to establish a private library. “The NAACP has tonight won a great victory.” The implication was clear: withdraw the suit, or Daniels would rejoin the four who wanted to keep the libraries closed.52 Others noted the negative national media attention Danville had received; in fact, even a widely circulated Soviet Union library journal covered the library closing, referring to the “dubious (from the standpoint of common sense) propositions” included in the citywide referendum.53

The move angered the Danville Bee, which called it “a surprising development in municipal government” that “certainly violates the principle of consent of the governed.” And why the $2.50 fee, especially in view of the fact that the city had invested $38,000 in building a recently completed wing, which the events of the last three months had only delayed? Especially galling was the NAACP’s “resounding victory,” which could “only open the door encouragingly to new racial triumphs. The NAACP does not have to do anything but to enjoy the privileges of the libraries now accorded them. Its court suit achieved its objective.” When the libraries opened the next day, seventy-five whites used the main library but no blacks; twenty-five blacks used the “former colored branch.”54

Two days later, federal judge Ted Dalton, who had replaced Judge Thompson after his untimely death in July, dissolved the injunction against the city and dismissed the suit without prejudice. NAACP attorneys vigorously protested, especially objecting to the “ultimatum” Catlin and Daniels issued publicly and the new $2.50 fee, which violated the principle of a “free” public library and would disadvantage poor people. The fee was an administrative matter, Judge Dalton responded, and the plan to reopen he thought had been adopted “in a spirit of good will.”55 It appeared the conflict had finally ended.

Unfortunately, the appearance of resolution was deceptive. Florence Robertson, librarian at the main branch, reported that traffic at the library was slow and that only “a few” black people had applied for library cards. Not surprising. As it turned out, the four-page library card application asked the applicant to provide, among other things, birthplace, college degrees, prospective use of the library, last grade of school completed, reading habits, and the hours one expected to use the library and how often. Furthermore, in addition to two character references and two credit references, each applicant had to list the type of books he or she planned to borrow and pay $2.50. The NAACP immediately filed suit, asking Judge Dalton to enjoin enforcement for the new rigid rules, but Dalton dismissed the suit on the ground that the library had been successfully integrated.56

Among the first black people brave enough to enter the library was nine-year-old Evans Hopkins. “I remember arranging to ride into town with a teacher after school, and rushing to the main library to delve into the books that had been denied me.” Once inside, however, he discovered all of the tables and chairs had been removed. “When I recall the shock of seeing the spitefulness of whites evidenced by the bare floors of that library,” he later recalled, “I began to understand how anger turns to rage.”57 Hopkins put that anger to good use in later years as a celebrated author featured in the New Yorker, the Washington Post, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among other publications. Simon and Schuster published his memoir in 2014.

Justifying the new library restrictions, the city manager explained the “stand up feature” would be in effect for only ninety days, a trial period to determine whether it would stay or “return to a normal operation.” He added that “within the next few days” patrons would be able to browse through the stacks. And concerning the $2.50 fee, he said, “I understand fully, of course, that the charging of a fee is not in keeping with standards established by professional librarians and yet, we felt that it was a necessary measure in bringing about the restoration of library service to the community.” He offered no further explanation. He also admitted that the long list of answers required for a card “may be a departure from the customary type that are contained in an application for library membership,” but he argued that the answers “will aid us considerably in planning the library program and facilities for the future.” He further justified his position by noting that he had library experience—he had worked in his university library while a student and after graduation had served on the board of visitors for his university, during which time they planned for a new campus library: “We do recognize the great need for adequate public library facilities. . . . Yet there are in our community many, many people who see little or no need for this service. You see, therefore, it is a problem that I believe only those of us on the local scene with previous background and experience can see objectively. Mrs. Robertson [the librarian] and I are trying desperately to keep the public library opened and have the services restored as nearly as possible to normal.”58

The ninety-day trial period was scheduled to expire December 11. On November 9, the city manager announced that “well spread out” tables and chairs would be returned to the library on December 10 and that the library’s 6:00 p.m. closing time would now be extended to 9:00 p.m. Although the librarian exercised discretion in assigning each user to a specific table for research, it appeared that, finally, the newly integrated library had resumed “normal” operations. During the subsequent year the number of library borrowers increased from 1,390 to 6,903.59

But the successful integration of the public library did not easily translate to other Danville public and private institutions. Lunch counters remained staunchly segregated, as did Danville schools and most other public and private facilities, despite the Supreme Court’s Brown decision. On August 23, 1962, civil rights attorneys filed a lawsuit against the city manager, city council members, the housing authority and school board, judges, parks and recreation directors, a hospital, and others. Demonstrations, protests, litigation, and violent confrontations between the police and demonstrators continued for the next year and a half, stretching even beyond the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In June 1963 police officers used fire hoses and sticks to disperse a crowd. Events in Danville during this traumatic period made the nonviolent integration of the public library seem almost effortless.

As was the case with Greenville, South Carolina, the integration of public libraries in Petersburg and Danville was forced by black high school and college students inspired by lunch counter and public accommodations sit-ins across the South. As in Memphis and Greenville, public libraries in Petersburg and Danville served as local platforms where the two races mediated their disputes, for blacks mostly through local NAACP chapters. And as in Memphis and Greenville, Petersburg and Danville’s public libraries were among the first local civic institutions to desegregate.

Louisville Public Library Children’s Room, 1928

(Caufield & Shook Collection, CS 091520, Archives and Special Collections, University of Louisville)

Sit-in arrest at the Alexandria, Virginia, Library, August 21, 1939

(From the Collection of the Alexandria Black History Museum, City of Alexandria, Virginia)

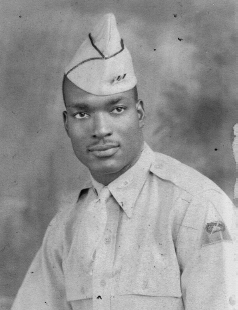

Jesse H. Turner

(Photo courtesy of Turner Estate)

Allegra W. Turner

(Photo courtesy of Turner Estate)

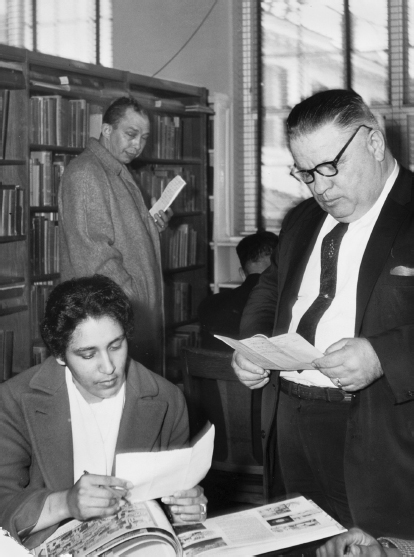

Petersburg chief of police W. E. Traylor serves warrant on Virginia State College student Lillian Pride, March 7, 1960

(Richmond Times-Dispatch)

African Americans assemble at Petersburg Courthouse, March 8, 1960

(Richmond Times-Dispatch)

Miles College student speaks to Birmingham public librarians, April 10, 1963

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group/Birmingham News)

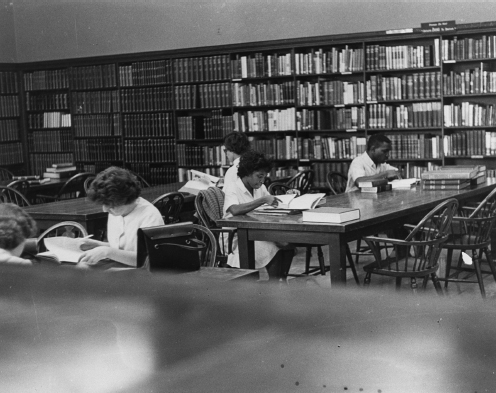

Sit-in at the Birmingham Public Library, April 10, 1963

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group/Birmingham News)

Albany Public Library, closed during the summer of 1962, with garbage can for book returns blocking front door

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division)

James “Sammy” Bradford surrounded by police moments before his arrest at the Jackson Public Library, March 27, 1961

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC 95515764)

Police escort the “Tougaloo Nine” from Jackson Public Library, March 27, 1961

(Associated Press photo)

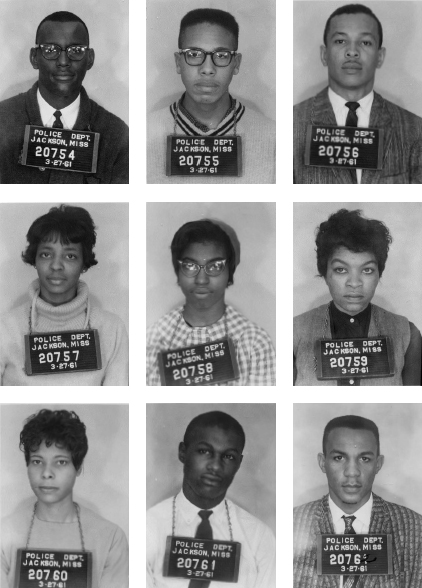

Mug shots of the “Tougaloo Nine” (from top left): Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Lassiter, Alfred Cook, Ethel Sawyer, Geraldine Edwards, Evelyn Pierce, Janice Jackson, James Bradford, and Meredith Anding

(Mississippi Department of Archives and History)

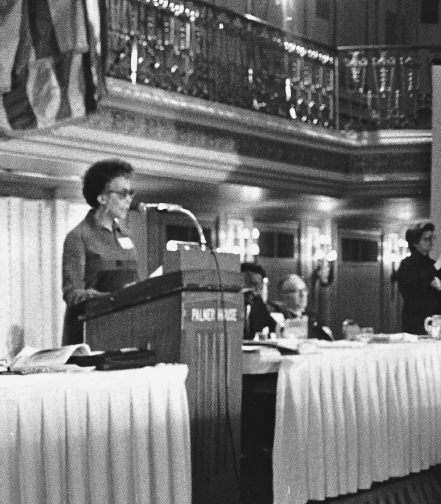

Clara Stanton Jones, first African American president of the American Library Association, addressing the ALA Council about The Speaker, summer 1978

(Courtesy of the American Library Association Archives)