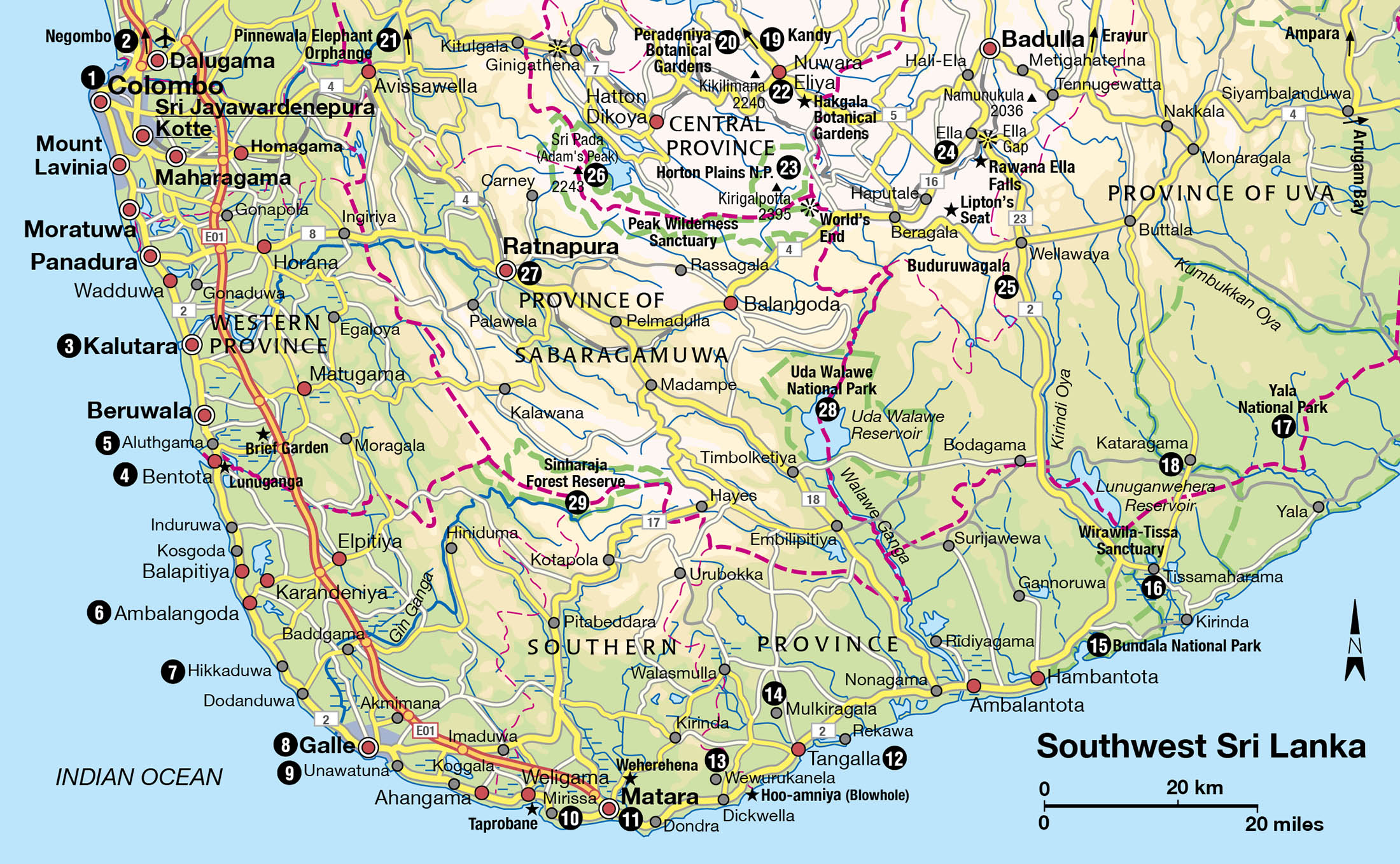

A classic Sri Lankan itinerary would include a few days in the Cultural Triangle, a tour through Kandy and the hill country, and a spell spent on the beaches of the southern or western coast. These places offer an overview of the island’s contrasting landscapes and complex history, but they are by no means all the country has to offer. Hiring a car and driver (for more information, click here) means you get to see a lot more than you otherwise would, but you still won’t get anywhere fast. You will, however, get a feeling for the island’s essentially rural lifestyle and sleepy pace of life.

A monk at the Gangaramaya Temple in Colombo

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Colombo

In a predominantly rural island, Colombo 1 [map] is Sri Lanka’s one true metropolis. Home to over three million people and most of the island’s significant commercial and industrial activity, the city sprawls along the west coast for the best part of 60km (40 miles), an endless straggle of chaotic and traffic-infested suburbs which can seem totally out of scale and character with the rest of the island. Unsurprisingly, this noisy, crowded and disorienting urban morass ranks low on most tourist itineraries, but despite initial impressions, there is plenty in the city’s contrasting districts and a handful of low-key sights to merit at least a day’s exploration.

Fort and the Pettah

The heart of old Colombo is Fort district, first established by the Portuguese, who constructed the now vanished fortifications after which the district is named. Once the centrepiece of Colombo’s commercial and administrative life, Fort bore the brunt of repeated LTTE attacks against Colombo during the civil war, and is now rather forlorn, with a heavy army presence and large areas closed off for security reasons. The heart of the district is marked by the distinctive Lighthouse Clock Tower A [map], erected in 1857, while other crumbling relics of 19th-century British enterprise lie dotted around, most notably the famous old Cargills department store. At the southern edge of the district rises an incongruous cluster of high-rises containing several five-star hotels and the twin towers of the World Trade Centre.

East of Fort stretches Colombo’s most absorbing area, the Pettah B [map], a crowded and chaotic bazaar district whose tight grid of streets is crammed full of an astonishing number of shops whose owners frantically trade everything from Ayurvedic herbs to mobile phones. At the heart of the district, the Dutch Period Museum C [map] (Tue–Sat 9am–5pm; charge) houses a modest selection of exhibits relating to Dutch life in colonial Sri Lanka in an atmospheric old villa. Just to the north is the Jami ul-Alfar D [map] mosque, the district’s most eye-catching landmark, its exterior decorated in bright red and white stripes.

Galle Face Green and Slave Island

South of Fort stretches Galle Face Green E [map], bounded to the north by the high-rises of Fort and the sprawling neoclassical Government Secretariat, and to the south by the famous old colonial Galle Face Hotel. A favourite city meeting place, the green really comes alive towards dusk when half the city descends on it to swap gossip, fly kites, enjoy the sea breezes and sample the unusual snacks served up by innumerable stalls set up along the promenade.

Seema Malaka temple by the waters of Beira Lake

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Heading inland from Galle Face Green, the ramshackle district of Slave Island (named after the African slaves once corralled here by the Portuguese and Dutch) is home to a cluster of Hindu and Buddhist shrines, including the city’s two most interesting Buddhist temples. The first is the unusual Seema Malaka F [map] (designed by Sri Lanka’s foremost 20th-century architect, Geoffrey Bawa), whose wooden buildings occupy three platforms set out over the waters of Lake Beira – particularly beautiful when illuminated at night.

Dutch deterrent

The Dutch discouraged slaves from attempting to escape Slave Island by keeping the surrounding canals and the waters of Beira Lake populated with a large number of crocodiles.

Just east of here, the more extensive and traditional Gangaramaya G [map] comprises a peaceful courtyard surrounded by shrines populated by assorted deities, including a huge modern ceramic Buddha. The quirky attached museum (charge) displays thousands of gifts presented to the temple over the years, including an unusual collection of vintage cars.

Southern Colombo

South of Slave Island, the serene suburb of Cinnamon Gardens is the city’s smartest address, with leafy roads lined with grand colonial villas and the peaceful Vihara Mahadevi Park, which stretches south of the modern town hall. The park is home to the National Museum H [map] (daily 9am–6pm with some sections closed for renovation; charge). Occupying one of Colombo’s finest colonial buildings, the museum’s extensive collection includes some fine ancient Buddhist and Hindu statuary, an excellent selection of kolam masks and the lavish regalia of the last king of Kandy.

South of Galle Face Green, southern Colombo’s major traffic artery, the smelly and congested Galle Road, strikes due south through the districts of Kollupitiya and Bambalapitiya, now home to many of the city’s top shops and restaurants, including the outstanding Barefoot shop and the beautiful Gallery Café (for more information, click here or click here). A few kilometres further south, Dehiwala Zoo (daily 8.30am–6pm; charge) is home to a comprehensive collection of international and indigenous wildlife, including a good selection of the island’s local fauna, from sloth bears to leopards.

At the southern edge of Colombo, 10km (6 miles) south of Fort, the laid-back suburb of Mount Lavinia offers a peaceful respite from the city streets to the north, presided over by the venerable Mount Lavinia Hotel, whose graceful white buildings provide the suburb’s major landmark. Although it is more popular with locals than with foreign tourists, the stretch of rather grubby beach here – the closest to the city centre – makes it a popular spot, particularly at weekends.

Ten kilometres east of Fort lies the Kelaniya Raja Maha Vihara, the most important Buddhist shrine in Colombo. Built to commemorate the third and last of the Buddha’s visits to the island, the modern temple complex comprises a vibrant and colourful array of modern paintings and sculptures, and is always lively with pilgrims.

The West Coast

Sri Lanka’s west coast is the most developed part of the island, and its innumerable large-scale resort hotels remain the driving force behind the country’s sizeable package-tourist industry. Much of the development here has been extensive and unregulated, and if you want unspoiled beaches and a true taste of the island’s fabled serenity you will have to head further south. Having said that, the west coast is home to many of Sri Lanka’s finest beachside hotels, both large and small, and still offers pockets of tropical charm, if you know where to look.

On the beach at Negombo

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Negombo and Around

Thirty kilometres (20 miles) north of Colombo, Negombo 2 [map] owes its popularity mainly to its proximity to the international airport, offering a convenient first (or last) stop on a tour of the island. The wide beach here has a plethora of guesthouses and resort hotels, and although there are far nicer beaches further south, Negombo has enough tropical charm to merit a day’s rest and recuperation after a long-haul flight. Tourists share the beach with the local Karava fishermen, whose flotillas of oruwa boats make a memorable sight as they return from offshore fishing trips during the early morning. Ingeniously constructed, an oruwa is fashioned from narrow canoes topped by an enormous sail which is kept steady in the water by cantilevered wooden floats. This type of vessel is known in Tamil as ketti-maran, the origin of the word ‘catamaran’.

South of the resort, Negombo town is dominated by the enormous pink bulk of St Mary’s Church, testament to the town’s status as one of the strongholds of Christianity on the west coast. The town was formerly an important Dutch settlement thanks to its strategic control of the lucrative local cinnamon trade and it preserves a few traces of its colonial heritage, including fragments of an old Dutch fort, as well as its old Dutch canal, which runs due north along the coast all the way to Puttalam, over 80km (50 miles) away. It is possible to organise boat trips along the canal or off the coast in oruwa boats as well as through the wetlands of Muthurajawela, south of the town, home to rich bird life and other fauna.

Oruwas returning to harbour

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Negombo fish market

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Kalutara

Just south of the great urban sprawl of Colombo, Kalutara 3 [map] has a long stretch of fine, though rather narrow, beach backed by a string of large-scale resort hotels. The lively town itself is worth a visit for the Gangatilaka Vihara, a picturesque temple whose enormous stupa looms imposingly over the main coastal road. The stupa also has the unusual distinction of being the only entirely hollow one in the world – step inside to experience the resonant echoes and murals depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life.

Beruwala, Bentota and Around

The epicentre of the Sri Lankan package-tourist industry lies further south at the twin resorts of Beruwala and Bentota. Beruwala is the most developed resort in the island, with a beautiful wide stretch of fine golden sand flanked by a dense concentration of hotels mainly catering for European sun seekers during the northern winter. South of here, Bentota 4 [map] has an equally fine swathe of sand, but the atmosphere is more laid-back, with a sequence of fine hotels strung at discreet intervals along the coast. Bentota is also the island’s water sports capital, with numerous activities ranging from jet-skiing to windsurfing on the tranquil waters of the Bentota lagoon, which meanders inland from here, and also offers a rewarding destination for boat trips into its tangled waterways and mangrove swamps. Both Beruwala and Bentota have a selection of diving schools, as well as the densest concentration of ayurvedic hotels on the island.

Sandwiched between Bentota and Beruwala, the workaday little town of Aluthgama 5 [map] is home to a cluster of attractive low-key guesthouses backing the Bentota lagoon, and offers a refreshing slice of everyday Sri Lankan life amidst the tourist development, with colourful fish and vegetable markets. A few kilometres inland lies the picture-perfect little estate of Brief Garden (daily 10am–5pm; charge), comprising a small but exquisite garden surrounding an artfully restored colonial villa stuffed full of artworks, photographs and other intriguing mementos collected by its former owner, Bewis Bawa, a famous Sri Lankan socialite, amateur artist and man-of-letters.

Brief Garden

Apa Publications

Bewis’s work in transforming Brief Garden inspired his brother, the great architect Geoffrey Bawa, to create a similar estate of his own at nearby Lunuganga (tours daily 9am–4pm; charge). Over four decades Bawa systematically enlarged and transformed the original house while adding a sculpture gallery, a string of quaint new outbuildings and sylvan terraced gardens overlooking the adjacent lagoon.

About 10km (6 miles) south of Lunuganga, Kosgoda beach is a favourite nesting site for marine turtles, with local villagers leading nightly turtle watches. Another 8km (5 miles) south, the village of Balapitiya is the starting point for rewarding boat trips along the Madu Ganga, dotted with over fifty islands and rich in local bird life.

Ambalangoda

About 25km (15 miles) south of Bentota, the small town of Ambalangoda 6 [map] is best known as the centre of the Sri Lankan mask-making industry, whose grotesque faces, representing various demons and humans, leer at you from shops and houses all over the south of the island. A copious selection of masks, and descriptions of the dances they were originally designed for, can be seen in the Ariyapala and Sons Mask Museum (daily 8.30am–5.30pm; charge). If you want to see the masks used in the dances for which they were originally intended, you may be able to watch rehearsals by students at the nearby Bandu Wijesurya School of Dance.

Some 6km (4 miles) inland from Ambalangoda, the obscure village of Karandeniya is home to Sri Lanka’s longest reclining Buddha – a super-sized collosus, the best part of 40m (130ft) long.

Island temple off the coast of Hikkaduwa

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Hikkaduwa

Close to the southernmost point of the west coast, Hikkaduwa 7 [map] offers a down-at-heel alternative to the big resorts further north. Back in the 1970s, Hikkaduwa was Sri Lanka’s original hippy hangout, and although uncontrolled development here has taken a massive toll on the beach and town, the resort remains modestly popular amongst backpackers, surfers and divers, and has a liveliness lacking in the sedate resorts further up the coast – while the launch of the hugely successful Hikkaduwa Beach Festival in 2008 gave the town a much needed shot in the arm. The famous Coral Sanctuary, a once-beautiful section of reef in shallow water just off the beach in the centre of town, is worth a visit. Hikkaduwa also offers some of the best surfing in Sri Lanka, as well as the island’s largest selection of diving schools.

Mask ritual

Sri Lanka’s most popular mask is Gurulu Raksha, a terrifying bird-like creature who is believed to prey on snakes and demons. Many people in the south hang Gurulu Raksha masks outside their houses to ward off malign influences.

The South

In many ways, the south is Sri Lanka at its most quintessentially Sri Lankan, with thousands of comatose villages, nestled under great swathes of palm trees, where the pace of life still travels at the speed of the bicycle rather than the car, and where coconuts are considered more important than computers. For visitors, the region offers a beguiling mixture of culture and hedonism. A long sequence of beautiful and largely unspoilt beaches is interspersed with national parks and some important Buddhist shrines – physical evidence of the south’s traditional role as a bastion of Sinhalese Buddhist culture.

Galle

The gateway to the south is the beautiful old settlement of Galle 8 [map] (pronounced ‘Gaul’), Sri Lanka’s best-preserved colonial city. First established by the Portuguese, the old part of the city, known as Galle Fort, achieved its present shape largely thanks to the Dutch, who erected a great chain of walls and bastions to protect the settlement from invaders. The streets inside are filled with atmospheric villas hidden behind enormous, shady verandahs and topped with crumbling red-tiled roofs – a wonderful place for an aimless and pleasantly traffic-free stroll.

Palm-fringed coast at Galle

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Entrance to the town is through the Main Gate A [map], a narrow portal cut into the enormous bastions, facing the cricket ground and modern city. From here, Church Street veers round to the left, taking you past several of Galle’s main sights, including the rather dull Galle National Museum B [map] (Tue–Sat 9am–5pm; charge) and the ultra-deluxe colonial Amangalla hotel, occupying a building originally constructed for the Dutch governor in 1684. Just past here is the intriguing Dutch Reformed Church C [map] of 1755: elegantly Italianate on the outside; severely plain within, apart from the many elaborately carved memorials to the city’s Dutch and British settlers.

Galle’s Historical Mansion Museum

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Continue south to the junction with Queen’s Street, marked by a further clutch of colonial buildings, including All Saint’s Church D [map], whose chunky little spire provides an important city landmark, and the sprawling orange bulk of the Great Warehouse. The latter now provides a home for the new National Maritime Museum E [map] (Tue–Sat 9am–5pm; charge), with a mildly interesting collection of old naval artefacts). Heading south along Leyn Baan Street brings you to the quirky Historical Mansion Museum F [map] (daily 9am–6pm; donation requested), home to a vast collection of antiques and bric-a-brac assembled by its owner over the past 35 years. At the southern end of Leyn Baan Street is the florid Meeran Jumma Mosque and the lighthouse, from where it is possible to walk (clockwise) around the bastions all the way back to the Main Gate.

Stilt fisherman of Ahangama

Shutterstock

Unawatuna to Mirissa

Past Galle, the coast is dotted with a string of small villages, which survive on a mixture of fishing, coconut farming and low-level tourism. A few kilometres beyond Galle lies the personable little village of Unawatuna 9 [map], which has long-since taken over from Hikkaduwa as Sri Lanka’s most popular backpacker destination. A beautiful semi-circular beach is backed by a cluster of informal little guesthouses whose rickety wooden structures and string of beachfront cafés lend the place a genuine ad hoc charm. Past Unawatuna, the coastal highway runs close to the sea, running through the small town of Koggala, home to the interesting Martin Wickramasinghe Museum (daily 9am–5pm; charge), with an intriguing collection of local artefacts relating to the traditional Sinhalese way of life. Beyond Koggala, the town of Ahangama is one of the best places in Sri Lanka to see the famous stilt fishermen, who sit perched on poles amidst the waves casting their lines in the waters. Immediately beyond Ahangama, the village of Midigama has a narrow beach, a handful of simple guesthouses and some of Sri Lanka’s best surf.

Rocky myth

The enormous rocky outcrop backing Unawatuna village, Rumassala, is popularly believed to have been dropped by the monkey god Hanuman during his adventures in Sri Lanka described in the great Indian epic, the Ramayana.

The next town of any consequence along the coastal highway is Weligama, a sleepy little place whose quiet streets are lined with chintzy villas decorated with ornately carved wooden eaves. In front of the town, the wide sweep of Weligama Bay is dotted with a couple of tiny islets, most notably Taprobane, topped by a crown of tropical greenery. The beach here is long, wide and largely untouched, although most visitors now prefer to crash out at the tiny village of Mirissa ) [map], on the headland at the far end of the bay, where a small stretch of golden sand nestles beautifully behind a thick screen of palm trees. It is also the centre for Sri Lanka’s burgeoning whale-watching scene; trips can be arranged through Mirissa Water Sports (www.mirissawatersports.lk) in the village.

Fishing boats at Weligama

Apa Publications

Matara

A few kilometres beyond Mirissa, the bustling little city of Matara ! [map] is the only settlement of any significant size in the south besides Galle. Like Galle, Matara rose to prominence under the Dutch, who fortified the town and made it an important settlement in the elephant and cinnamon trade. A line of coral-stone ramparts divides the modern city from the old colonial district, or Fort, which is bisected by peaceful streets of decaying old villas.

Much of the modern town lies on the north side of the palm-lined waters of the Nilwala Ganga river, and it is worth crossing over to visit the quaint little Dutch Star Fort of 1763, now home to a modest museum. A couple of kilometres outside town, the modern temple at Weherehena is home to one of the biggest Buddhas in the island, a 39m (129ft) gaudily painted colossus seated in deep meditation.

Tangalla and Around

There is another decent beach (and some good snorkelling) in the suburbs of Matara at Polhena, but most foreign tourists press on either west to Mirissa and Unawatuna, or further east to Tangalla @ [map], where more beaches dot the coast on either side of the scruffy little town. Although the beaches here are not as nice as others along the south coast, Tangalla has the bonus of a number of interesting sights in the surrounding countryside, which are easily combined in a half-day’s excursion. These include the unusual blowhole at Hoo-amaniya, where a narrow cleft in the rock at the edge of the ocean sends enormous plumes of water up to 15m (50ft) high into the air; and the temple at Wewurukannala £ [map], whose impressive complex is home to another gigantic Buddha statue; at around 50m (160ft) high even bigger than the one at Weherehena.

The temple at Wewurukannala

Apa Publications

Close to Tangalla is another major man-made attraction: the rock temples of Mulkirigala $ [map] (daily 6am–6pm; charge). Something of a cross between Dambulla and Sigiriya, the temples are carved into the flanks of a majestic rocky outcrop which rises dramatically out of the predominantly flat surrounding landscape. Seven hundred steps lead to the top, passing a sequence of temples arranged on four terraces and filled with ornate Buddha statues and wall paintings dating back to the 18th century. At the top, the effort of the climb is rewarded by marvellous views south to the coast and north to the rolling uplands of the hill country.

Turtle talk

Turtles are amongst the oldest reptiles on the planet, offering a living link with the age of the dinosaurs. They can grow to up to 3m (10ft) in length, live more than 100 years, dive to depths of a kilometre and hold their breath for half an hour – as well as migrating for distances of up to 5,000km (3,000 miles).

Bundala National Park

Continuing east along the coast from Tangalla brings you to Rekawa, whose beach is one of the most important turtle-nesting sites in the islands. Locals here organise ad hoc nightly turtle watches (charge), during which it is possible to get a glimpse of them dragging themselves laboriously up onto the beach to bury their eggs in the sand.

Beyond Rekawa, the landscape changes as you enter the island’s dry zone, the lush palm forests of the west and southwest coasts giving way to an arid, savannah-like scenery which receives far less rainfall than the areas behind. The first of the area’s two excellent national parks, Bundala National Park % [map] (daily 6am–6pm; charge), is famous principally for the immensely varied aquatic and other bird life found in the park’s coastal wetlands and lagoons. Almost 200 species of bird have been recorded here, including the prolific flocks of greater flamingos which arrive from northern India. A large population of wild peacocks adds a distinctive and colourful flourish to the park’s tangled grey-green woodlands. Birds apart, Bundala is also home to a rich stock of wildlife including troupes of hyperactive grey langur monkeys, a small number of elephants and ferocious-looking crocodiles, plus sloth bears, civets, giant squirrels and the occasional leopard.

Tissamaharama and Yala

Beyond Bundala the coastal highway veers inland to reach the pleasant town of Tissamaharama ^ [map] (usually shortened to ‘Tissa’). The town offers a convenient base for trips to Bundala and Yala National Parks, as well as the temple town of Kataragama, but is also of some historical interest in its own right, occupying the site of the ancient former southern capital of Mahagama. A trio of large stupas strung across the town attest to its former importance, as does the beautiful Tissa Wewa, an artificial lake just north of the modern town centre created in the 2nd or 3rd century BC.

For most visitors, Tissamaharama’s major attraction is its proximity to Yala National Park & [map] (daily, flexible opening hours dependant on weather conditions; charge), one of the largest and certainly the most popular in Sri Lanka. The principal attraction here is leopards (Yala has one of the densest concentrations of these elusive felines anywhere in the world), while there are also elephants, sloth bears, spotted deer, mongooses, porcupines and a compelling array of bird life.

An inquisitive giant squirrel

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Kataragama

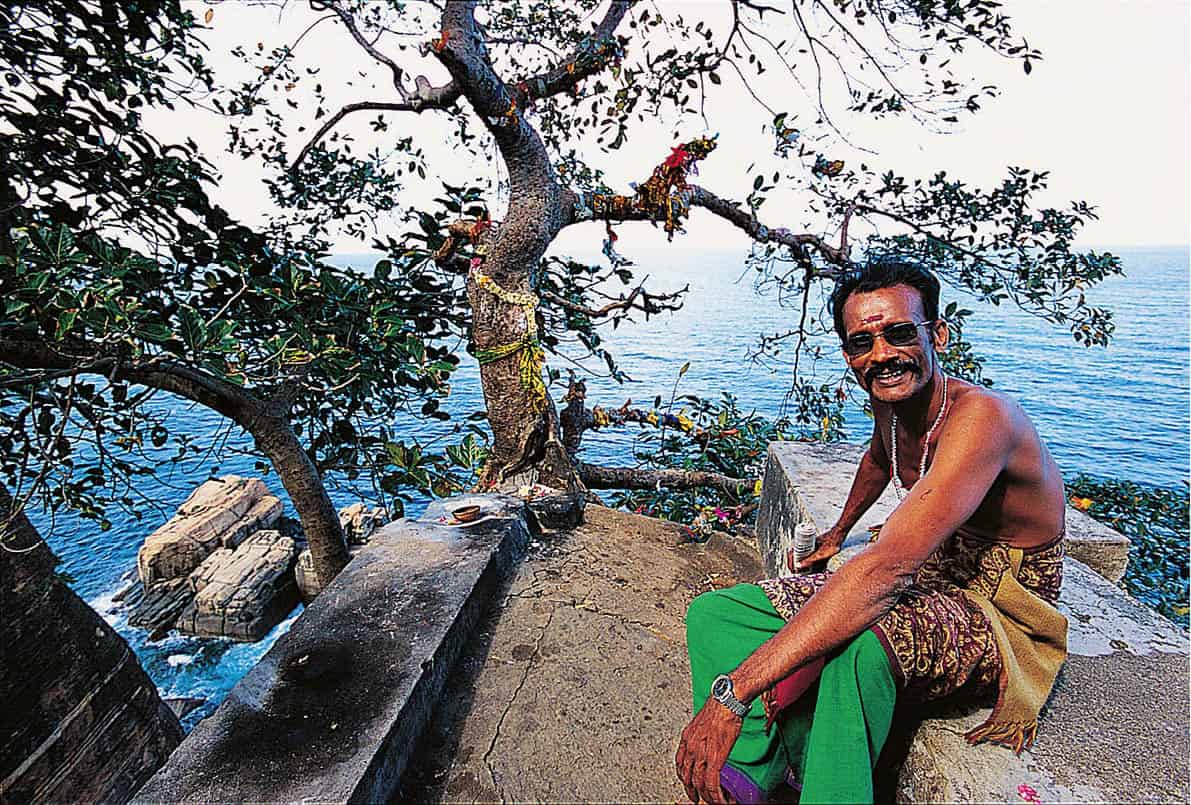

Inland from Tissa lies the remote temple town of Kataragama * [map], one of the island’s most revered pilgrimage sites, held sacred by Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims alike. The town owes its importance to the presence here of the island’s principal shrine to the god Kataragama, a deity of typically confused Sri Lankan lineage.

Named after the town in which his shrine is located, Kataragama is seen by Sinhalese Buddhists as one of the island’s four great protective deities. Sri Lankan Tamils regard him as a local manifestation of the great Hindu god Skanda, son of Shiva, lending the shrine a multi-faith significance that transcends strict ethnic and religious divides.

Drummers at Kataragama

Apa Publications

Kataragama’s shrine, the shrines of other attendant deities and a large stupa and a mosque, occupy the so-called Sacred Precinct, a pleasant area of parkland populated by innumerable curious grey langur monkeys and separated from the modern town by the Menik Ganga, in whose waters pilgrims bathe before approaching the temple. The town and temple are quiet by day, but come dramatically alive during the nightly puja, with musicians, singers, dancers and crowds of pilgrims bowed down with huge bowls of fruit as offerings. The scene is at its most dramatic during the annual Kataragama Festival (July/Aug), when the god’s more ecstatic followers perform gruesome acts of devotion and penance including walking across burning coals and piercing their flesh with long metal skewers.

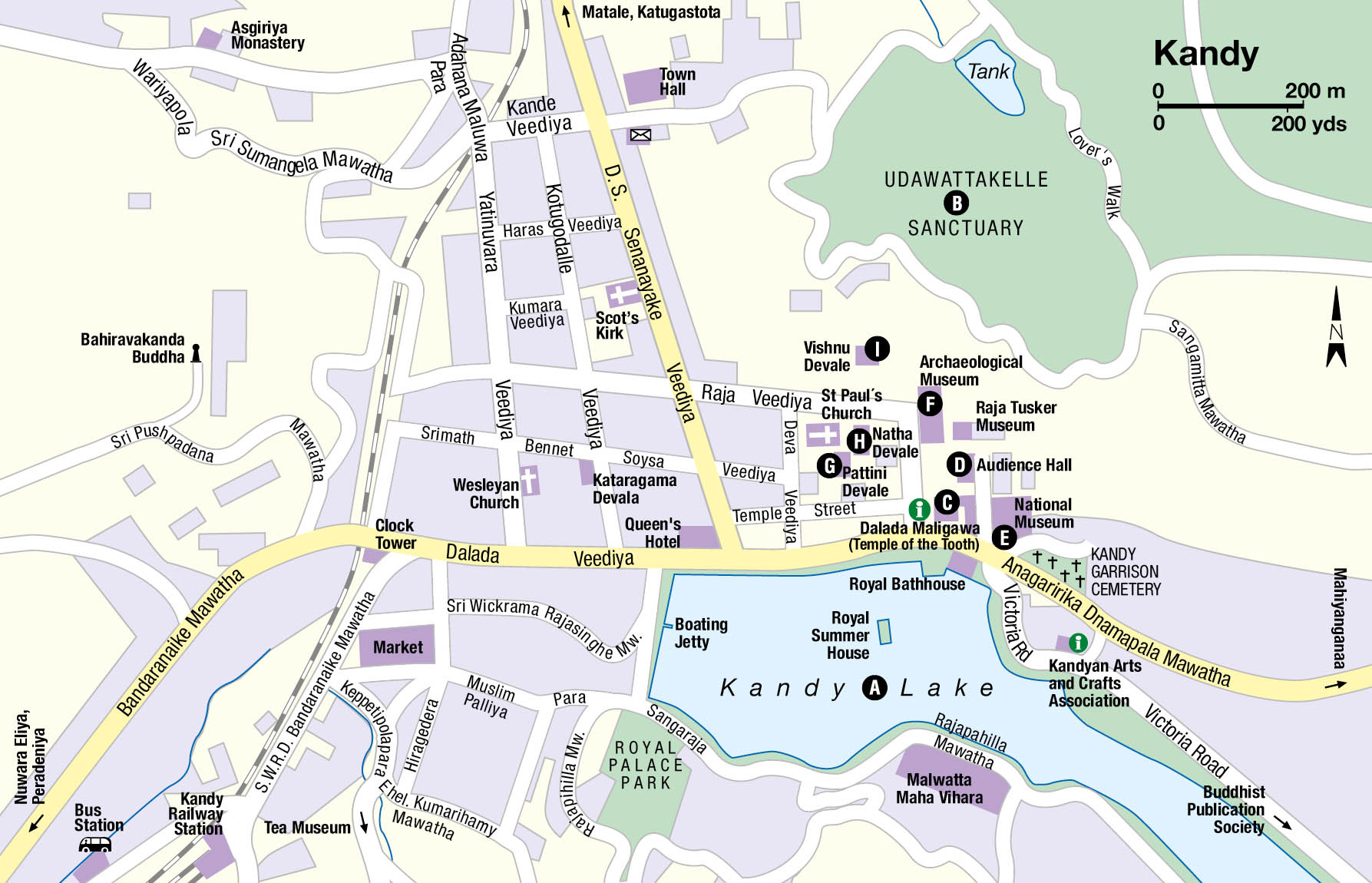

Kandy

Nestled amongst spectacular green mountains at the heart of the hill country, Kandy ( [map] is the definitive Sri Lankan city, home to the country’s most revered shrine, its most vibrant performing arts tradition and its greatest festival, the Esala Perahera (for more information, click here). The last bastion of independent Sinhalese rule in Sri Lanka, the Kandyan Kingdom served as the crucible of the island’s distinctive Sinhalese Buddhist culture, resisting repeated attacks by the Portuguese and Dutch before finally falling to the British in 1815.

Kandy’s lakeside Temple of the Tooth

Apa Publications

Kandy is now the island’s second-largest city, but although there are crowds and traffic aplenty, the city’s low-rise streets, numerous historic monuments and extensive tracts of surrounding greenery lend it a refreshing small-town atmosphere compared with the great sprawl of Colombo. There is enough in the town and surrounding countryside to keep anyone occupied for weeks, ranging from Buddhist temples to elephant sanctuaries, and a visit of at least a day or two is an essential part of any tour of the island.

The Lake and Around

The centre is dominated by the large artificial Kandy Lake A [map], created by the last king of Kandy, the infamous Sri Wickrama Rajasinha, using forced labour, although its placid waters give no hint of its unsavoury origins. Just south of the lake, the small Royal Palace Park offers fine views over the town and temples. There are even more extensive views from Rajapihilla Mawatha, a road that winds high above the southern side of the lake, giving incomparable panoramas across the city. The city centre, to the west of the lake, consists of a tight grid of busy streets overlooked by the vast Bahiravakanda Buddha, posed serenely on a hill overhead.

Traditional Kandyan dancer

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The dense green forest covering the steep hillside immediately behind the Temple of the Tooth is part of the beautiful Udawattakele Sanctuary B [map] (daily 6am–6pm; charge), a totally unexpected miniature, tropical wilderness almost in the heart of the centre of town. There are paths and tracks through the woods which are home to a rich array of bird life, the occasional monkey and (if it has been raining) a considerable number of leeches. It’s a beautiful spot, though a hefty entrance charge is levied on foreign visitors.

Temple of the Tooth

The Temple of the Tooth C [map], or Dalada Maligawa (daily 6am–8pm; charge), is home to Sri Lanka’s most revered religious relic, the Buddha’s Tooth, which attracts pilgrims from across the island, and indeed from many other Buddhist countries around Asia. Sitting on the north shore of the lake, the temple comprises a picturesque complex of neat white buildings topped with hipped roofs, framed against the luxuriant green slopes of the Udawattakele Sanctuary, and the entire ensemble is beautifully reflected in the waters of the lake.

The Buddha’s Tooth

One of the world’s most revered Buddhist relics, the Buddha’s Tooth was recovered from the master’s funeral pyre at Kushinagar in north India in 543BC and, following the decline in Buddhism in India, smuggled into Sri Lanka in the 4th century AD. Once in Sri Lanka, the Tooth Relic developed into the defining symbol of Sinhalese sovereignty, so that whoever possessed it was believed to hold the right to rule the island, lending it a unique political as well as spiritual importance. The Tooth Relic was first taken to Anuradhapura, then to Polonnaruwa, and then to various other places around the island before finally arriving in Kandy in 1592, where it became the focus of the massive Esala Perahera festival (for more information, click here). Security concerns mean that the Tooth Relic is now only rarely put on display to the general public, though its appeal amongst Sri Lankan Buddhists remains undimmed. Its exact nature remains unclear, however – one sceptical Portuguese visitor suggested that its unusual size was due to the fact that it originally belonged to a buffalo.

Heavy security marks the approach to the temple, the result of an LTTE bomb attack in 1998 which badly damaged the facade. Beyond the various checkpoints, an elegant white outer wall and moat enclose the temple, while to the left is an eye-catching octagonal tower, the Pittirippuva, from which all new Sri Lankan heads of state come to address the nation.

Inside, the temple buildings cluster around a single, surprisingly small courtyard, in the middle of which stands the Tooth Relic shrine, ornately decorated with wall paintings, elephant tusks, richly carved stone pillars and three lavishly carved doors. The tooth itself is housed in a room on the upper storey of the shrine, which is opened for daily pujas at 6am, 9am and 6.30pm, a ceremony enlivened with exuberant Kandyan drumming. The tooth remains locked carefully away in an elaborate golden reliquary in the innermost room of the shrine, and is shown only to the most important of visitors. At the rear of the courtyard, the modern Alut Maligawa shrine, built in 1956, houses a large collection of Buddha statues donated by Buddhists from all over the world. The rooms above this are home to the Sri Dalada Museum which is devoted to the Tooth Relic, and in particular to the large and eclectic selection of gifts presented as offerings over the centuries.

Inside the Tooth Relic Shrine

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Royal Palace Complex

The Temple of the Tooth was formerly just one part of the Royal Palace complex, home to the kings of Kandy, whose surviving buildings enclose the temple and now house a sequence of museums. Exiting the temple to the north brings you to the imposing Audience Hall D [map], a grand pavilion whose characteristic hipped roof is supported by dozens of lavishly carved wooden pillars – a classic example of open-plan Kandyan-style architecture. Just beyond here, a more modest building houses the Raja Tusker Museum, home to the stuffed remains of the much-loved Raja, a magnificent pachyderm which was until his death in 1988 the leading elephant in the city’s Esala Perahera festival.

Kandyan dancing

Performances of Kandyan dancing and drumming are staged nightly at several venues around town – touristy but enjoyable spectacles in which sumptuously costumed dancers perform superbly acrobatic routines to an accompaniment of wildly energetic drum beats.

To reach the remaining buildings of the Royal Palace, it is necessary to leave the temple and head outside along the shore of the lake. On the lakefront by the south side of the temple lies another striking Kandyan-style building, the two-storey Royal Bathouse (Ulpenge). Immediately beyond is the extensive National Museum E [map] (Tue–Sat 9am–5.30pm; charge), which houses an extensive collection of antique Kandyan artefacts ranging from palm-leaf manuscripts to ivory jewellery. Continue away from the lake past the British courts to reach the Archaeological Museum F [map] (Wed–Mon 8am–5pm; charge). Housed in a fine old building which was formerly the king’s palace, it is now home to a jumble of old stone carvings, pillars and pots. Finally, hidden behind the National Museum, the lovingly restored Kandy Garrison Cemetery is home to an atmospheric cluster of memorials to the city’s early British inhabitants, the inscriptions on the headstones painting a vivid picture of the perils of life in the tropics in the 19th century.

The Devales

The northern side of the Temple of the Tooth precinct is bounded by the atmospheric enclosures of the three devales (temples), dedicated to three of the four deities who are traditionally thought to protect the Kandyan kingdom (the fourth devale, an interesting little shrine dedicated to the god Kataragama, lies nearby in the city centre on Kotugodelle Vidiya). Approached through a gateway to the left of the entrance to the Temple of the Tooth, the Pattini Devale G [map] is dominated by an enormous bo tree raised on a huge stone platform. The temple itself, a small but lavishly decorated building, stands just to the right of the entrance. Next to here is the Victorian St Paul’s Church, an incongruous Anglican intrusion in this most sacred Buddhist precinct, whose beautifully preserved interior offers a moving memorial to the city’s early British settlers.

Continue through the Pattini Devale to reach the Natha Devale H [map], a quaint collection of stupas and small shrines. Its principal shrine (on the south side of the enclosure), occupies a diminutive stone building, topped by an Indian-style shikhara dome, which is the oldest building in Kandy. Heading left out of the Natha Devale brings you to the finest of the three devales, the Vishnu Devale I [map], whose main building, approached via a long flight of steps, houses a wooden pavilion, or digge, traditionally used as a practice venue by the city’s drummers and dancers.

Botanical Garden blooms

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Peradeniya Botanical Gardens

The countryside around Kandy offers several rewarding day trips. Just 6km (4 miles) outside the city, the extensive Peradeniya Botanical Gardens , [map] (daily 7.30am–5pm; charge) are the finest in the country, home to a vast array of tropical flora set in a bend in the Mahaweli Ganga. The minimal signage means that non-botanists will struggle to get a full sense of what they are seeing, although the basic map available at the entrance gives a rough idea of the gardens’ layout and content. From the entrance, the stately, much-photographed Royal Palm Avenue leads down to the Great Lawn at the centre of the gardens, where a massive Javan fig has created an enormous arboreal pavilion, normally busy with picnicking locals. Beyond here, the northern section of the gardens is the wildest, home to an enormous population of fruit bats who hang in great clusters from the trees overhead.

Pinnewala Elephant Orphanage

An hour’s drive west of Kandy lies one of the island’s most popular attractions, the Pinnewala Elephant Orphanage ⁄ [map] (daily 8.30am–6pm; charge), the world’s largest collection of captive elephants. The orphanage is home to more than 80 animals orphaned or injured in the wild, mainly as a result of the innumerable clashes between elephants and villagers which, sadly, are an ongoing feature of life on the island – as well as an increasing number of elephants born here in captivity. The elephants range in age from the stately elderly matriarchs to the tiniest and cutest of baby pachyderms. Visits are best timed to coincide with the three daily feeding and bathing sessions (9.15am, 1.15pm and 5pm). During the feeding sessions, the younger elephants are hand-fed from enormous bottles of milk, while twice daily the entire herd is driven down to the Ma Oya river to splash around in the water for an hour or so – a marvellous sight not to be missed, despite the fact that the elephants are regularly outnumbered by the hordes of camera-toting tourists who congregate for the spectacle.

Residents of the Elephant Orphanage

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The only drawback to Pinnewala is that it is not possible to interact with the elephants, or to learn much about them. For this, you’ll need to visit the nearby Millennium Elephant Foundation (daily 8am–4pm; charge), home to nine elephants (mostly retired working animals) and a good place to learn more about their role in Sri Lankan life and culture; they also run elephant-related volunteer programmes to help the animals.

The Hill Country

Occupying the southern heart of the island, the hill country is Sri Lanka at its most scenic: a magnificent region of precipitous green mountains carpeted with lush tea plantations and dotted with tumbling waterfalls and old-world British colonial memorabilia – gothic churches, half-timbered villas and rattling railways – which add a quaintly whimsical touch to the highlands’ compelling natural attractions.

For most of the country’s history this beautiful but rugged region was sparsely populated and, with the exception of the area around Kandy, of minimal political significance. But with the arrival of the British and the introduction of large-scale tea cultivation in the 19th century, the area assumed an increasing economic importance, one that it maintains to this day. The arrival of thousands of Indian Tamils (the so-called ‘Plantation Tamils’) to work the tea estates added a further splash of ethnic colour to this fascinating region.

Nuwara Eliya and Around

At the heart of the southern hill country lies the old colonial resort of Nuwara Eliya ¤ [map], the highest town in Sri Lanka, dominated by the densely forested bulk of Pidurutalagala, or Mount Pedro, the island’s tallest peak at 2,524m (8,281ft) (although sadly the summit itself is off limits).

First established by the British in the 19th century, Nuwara Eliya is often touted as Sri Lanka’s ‘Little England’, and although much of the modern town is now an unattractive mess of concrete buildings and noxious traffic fumes, the open spaces of Victoria Park and the golf course add some welcome greenery to the modern centre. The edges of town still sport a fair sprinkling of atmospheric colonial-era villas and hotels whose incongruous architecture – a mix of fake-half timbering and brightly painted seaside-style architecture – add a pleasant touch of old-world charm. Many of the town’s colonial-era buildings have now been converted into engagingly atmospheric hotels, most strikingly Jetwing St Andrew’s, the Grand and, most famously, the Hill Club, a venerable old stone building whose nostalgic interior offers a memorable glimpse of colonial life in the tropics.

Mountain scenery around Nuwara Eliya

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The town also makes an excellent base for exploring the surrounding region, and has wonderful scenery in its immediate vicinity, most easily enjoyed by making the short walk up Single Tree Mountain, from where there are marvellous panoramas over the surrounding mountains. Slightly further afield are the Hakgala Botanical Gardens (daily 8am–5pm; charge), set at the foot of the imposing Hakgala Rock. Established in 1861 as a place to grow cinchona, a source of the anti-malarial drug quinine, the gardens were later planted with an extensive range of local and foreign flora and offer a beautiful retreat from the hustle and bustle of Nuwara Eliya, as well as an excellent place to spot some of Sri Lanka’s rare endemic montane bird species.

Nuwara Eliya also lies at the heart of the Sri Lankan tea industry, with mile upon mile of the surrounding hills carpeted in endless swathes of lush green tea bushes. Two local tea plantations welcome visitors: the Pedro Tea Estate, just 3km (2 miles) east of town, and the beautiful Labookelie Estate further away to the north. Both offer interesting factory tours to see how the leaf is processed and the chance to wander amongst the immaculately manicured surrounding plantations.

Sri Lankan Tea

The tea industry played a formative role in Sri Lanka’s early commercial history, and although it has now been overtaken in importance by the garment-manufacturing and tourist industries, it retains a crucial role in the island’s modern economy. Sri Lanka remains the world’s second largest exporter of the beverage, after India, and the tea industry accounts for around a quarter of the country’s export earnings. The suitability of the island’s central highlands – with their wet, elevated and steeply shelving terrain – for tea growing was first recognised by the British, who began enthusiastically establishing plantations here following the collapse of the island’s coffee industry in the second half of the 19th-century. Many of the factories and estates they established remain in operation to this day, still largely worked by the descendants of the original ‘Plantation Tamils’ who were brought by the British from India to address the labour shortage in the highlands. In general, the higher the plantation, the more delicate and sought-after the tea. The so-called ‘high-grown’ tea from the premier estates around Nuwara Eliya remains amongst the most highly prized in the world market today.

Horton Plains and World’s End

The most memorable attraction within striking distance of Nuwara Eliya is Horton Plains National Park ‹ [map] (daily 6.30am–6.30pm; charge), lying on the very edge of the hill country. The plains are a world away from the humid lowlands: a bleak, mist-shrouded expanse of moorland, more reminiscent of Scotland than a tropical island, dotted with strands of tangled cloud forest. At the southern edge of the park, the unforgettable viewpoint at World’s End offers perhaps Sri Lanka’s finest and most famous panorama (the unpredictable weather permitting; get there early - 6-10 am is the best time to visit), perched on the edge of a huge, sheer cliff face which plunges almost 1,000m (3,300ft) to the lowland plains below.

Harvesting tea

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Haputale

East of Horton Plains, a string of small towns and villages sit atop the escarpment at the southern edge of the hill country, all offering magnificent views and scenery, extensive tea plantations, and occasional colonial memorabilia.

There are more stunning views from the ramshackle little town of Haputale, perched on the very edge of the hills, and memorable walks in the vicinity. The finest route heads out of town to the picturesque Dambatenne Tea Factory and its beautiful tea gardens, then climbs up to Lipton’s Seat, named after the famous Victorian tea magnate whose name still adorns tea bags worldwide, and which is a serious rival to the better known World’s End viewpoint.

Ella and Around

Most visitors, however, press on to Ella › [map]: a charming little English-style village poised above Ella Gap, and offering further superlative views through a narrow cleft in the hills down to the plains below. The village itself is one of the most relaxing places in Sri Lanka to unwind for a few days, with a plethora of small, unassuming but enjoyable guesthouses serving up some of the best home cooking on the island. You can work up an appetite by tackling some of the wonderful walks through the surrounding tea plantations, most notably the short but rewarding hike up Little Adam’s Peak and the longer, more challenging ascent of Ella Rock.

Monks at Ella Falls

Apa Publications

Ella is also a good base from which to explore the area’s myriad attractions. Just below the village, the majestic Rawana Ella Falls tumble down a series of sheer cliff faces. This is one of the finest of the hill country’s many waterfalls and one of several places around Ella named after Rawana, the demonic villain of the great Indian epic the Ramayana, who it is claimed imprisoned Rama’s wife Sita in a cave nearby. After the Falls, the road hairpins dramatically down to the dog-eared little town of Wellawaya, which lies at the foot of the escarpment. Just beyond are the statues of Buduruwagala fi [map], a majestic sequence of seven figures carved in low relief into a towering rock face and showing, for Sri Lanka, an unusual selection of deities, including the Mahayana Buddhist deities Avalokitesvara and Maitreya alongside the Buddha himself.

Adam’s Peak

At the opposite end of the southern hill country, west of Horton’s Plains, the soaring summit of Adam’s Peak fl [map] towers high over the lowlands below. The mountain is both one of Sri Lanka’s most dramatic natural features and also one of its most revered pilgrimage sites thanks to the small and curiously shaped depression on the summit that is popularly claimed to be the Buddha’s Footprint, or Sri Pada. Not to be left out, the island’s Hindus, Muslims and Christians subsequently came up with their own legends claiming that the footprint is that of Shiva, Adam and St Thomas respectively – though none of these claims has ever gathered much popular support.

Adam’s Peak, the perfect shadow, seen at dawn

Apa Publications

During the pilgrimage season (Dec/Jan–May), thousands of pilgrims make the arduous ascent up the 4,800 steps that lead to the summit. Traditionally, the climb is made in the cool of the night in order to reach the summit by dawn. In season, the steps are illuminated and dotted with impromptu teashops offering refreshment to weary pilgrims. Not only does this night-time ascent offer the best odds of a cloud-free view from the top, but it also gives you the chance to see the peak’s famous shadow, a perfectly triangular mirage cast by the summit, which seems to hang mysteriously in mid-air for 20 minutes or so following sunrise, weather permitting. Buddhists believe that this shadow is a physical representation of the ‘Triple Gem’, a kind of Buddhist Holy Trinity symbolising the Buddha, his teachings, and the Sangha (a community of Buddhist monks).

Ratnapura and Around

The town of Ratnapura lies directly south of Adam’s Peak, though to reach it by road involves a long and circuitous road journey either south through Balangoda or northwest through the dramatic ranges at the western edge of the hill country to Kitulgala. Kitulgala is famous as the spectacular location for the filming of the Oscar-winning The Bridge on the River Kwai and is now a popular centre for white-water rafting on the choppy waters of the Kelani Ganga.

The sizeable town of Ratnapura ‡ [map] itself is the largest in the region, pleasantly situated amidst the southern ranges of the hill country and famous as the centre of the island’s gem-mining industry. Enormous quantities of precious stones are excavated by hand from the alluvial deposits washed down from the hills here using primitive and labour-intensive mining techniques. You can watch uncut gems being traded in town along Saviya Street (though rip-offs are common, and it is best not to buy unless you are an expert gemologist), and it is also possible to arrange visits to local ‘mines’ (effectively just large holes in the ground) in order to watch local gem-diggers in action.

Uda Walawe and Sinharaja

For many visitors, however, the main attraction of Ratnapura is as a base from which to visit the two outstanding national parks nearby. The popular Uda Walawe National Park ° [map] (daily 6.30am–6.30pm; charge), is just south of the hill country. Although the park’s arid and denuded landscape is relatively unimpressive, the lack of forest cover makes it one of the easiest places in the island to spot wildlife, including the park’s large elephant population.

Sinharaja rainforest

Shutterstock

West of Uda Walawe, draped over the undulating southern outliers of the hill country, Sinharaja Forest Reserve · [map] (daily 8am–6pm; charge) protects the island’s largest surviving stretch of tropical rainforest. Sinharaja is quite unlike anywhere else on the island. The world inside the forest is positively Amazonian: trees, creepers, ferns, lianas and epiphytes, all tangled together in damp exuberance.

The forest is a treasure box of ecological curiosities containing no fewer than 830 species of endemic flora and fauna, including monkeys, reptiles, many rare bird species and a baffling array of insect life, although the density of the reserve’s vegetation and the height of the forest canopy makes wildlife-spotting surprisingly difficult without the services of a trained guide.

The Cultural Triangle

North of the hill country stretch the plains of the northern dry zone, a great stretch of hot, denuded savannah, covered in thorny scrub and dotted with dramatic rocky outcrops. Despite the harshness of the natural environment, these plains were home to the remarkable civilisation of the ancient Sinhalese, which flourished here from around the 4th century BC until the 13th century AD. Their cultural, agricultural and architectural achievements ranked amongst the finest in the ancient world, until they were finally destroyed by repeated Tamil invasions.

Following the abandonment of the plains, the region’s two great cities and innumerable smaller religious sites were largely abandoned to the jungle until they were recovered by 20th-century archaeologists. Their collective remains – a remarkable array of stupas, temples, palaces, monasteries and monolithic Buddha statues – offer a fascinating insight into the unique arts and culture of Sri Lanka’s early Sinhalese people.

The Cultural Triangle Ticket

Round trip tickets covering all of the Cultural Triangle’s main attractions are no longer available so visitors must pay separately for each site.

This area of the island is now commonly described as the Cultural Triangle (with the three points of the imaginary triangle being placed at the cities of Kandy, Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa). This is a convenient modern tourist name for the region, although it is also, and more accurately, known by its ancient name of Rajarata, or ‘The King’s Land’.

North from Kandy to Dambulla

A handful of interesting sights dot the countryside between Kandy and Dambulla, including a trio of temples which merit a visit on the journey north. The first, right next to the main highway, just north of the town of Matale is Aluvihara, an interesting Buddhist monastic complex featuring a sequence of cave temples hidden amidst enormous rock outcrops.

Dambulla Rock Cave Temples

Apa Publications

The complex is famous mainly for being the place where the principal Buddhist scriptures, the Tripitakaya, were first written down, an event which had enormous significance in the international development of the religion.

Hidden away a few miles west of the highway in a beautiful rural location in the village of Ridigama, Ridi Vihara is one of the most interesting small temples on the island, housing a range of ancient sculptures and other rare artefacts. Back on the main road and continuing north, the exquisite little stone temple at Nalanda (charge, or free with CT ticket), was built as a Buddhist shrine, though in a style which is strongly reminiscent of Hindu Indian architecture, and even includes a couple of erotic carvings, now heavily eroded almost beyond recognition.

Dambulla

North of Nalanda, more or less at the centre of the Cultural Triangle, the imposing 160m (52ft) Dambulla Rock º [map], just south of the dusty and workaday town of Dambulla, houses the most impressive and venerated Buddhist cave temples. There are five temples here, filled with a veritable treasury of Buddhist art, including innumerable statues of the Buddha and other deities, plus the finest selection of murals on the island.

Maharajah Vihara at Dambulla

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The finest of the rock temples, Caves 2 and 3, are masterpieces of Sinhalese art. Cave 3, the Maha Alut Viharaya, reaches a height of 10m (33ft), with a sloping roof which gives it the appearance of an enormous tent. As well as the cave’s fine Buddha statues, some carved from solid rock, there are outstanding murals (look up at the ceiling as you enter the cave) showing the Buddha preaching and (to the left of the entrance) a statue of the Kandyan king Kirti Sri Rajasinha, who was largely responsible for the temples’ 18th-century embellishments.

Even larger and finer is Cave 2, the Maharaja Vihara, a vast underground space some 50m (165ft) long crammed full of religious artworks, including more than a hundred Buddhas ranged around the walls in various poses. There is also an eye-boggling collection of murals, including the extraordinary Mara Parajaya, showing the Buddha’s defeat of Mara and his massed regiments of hairy demons; and the seductive Daughters of Mara, in which the Buddha is shown resisting the considerable attractions of the demon’s legion of comely daughters.

Sigiriya

Sri Lanka’s most remarkable single attraction, the spectacular citadel of Sigiriya ¡ [map] (daily 7am–5.30pm; charge), sits atop a vast gneiss outcrop which towers more than 200m (650ft) above the surrounding plains at the heart of the Cultural Triangle. The citadel was established in the 5th century by the infamous Kassapa, who murdered his father and assumed the kingship of the island, establishing a new and impregnable fortress-palace atop Sigiriya rock. Kassapa ruled the island from here for 18 years before being killed in battle, after which Sigiriya was abandoned.

The entire eastern side of the rock is surrounded by an extensive moat, past which an avenue arrows towards the rock, crossing a series of elaborate pleasure gardens. The first section, the Water Gardens, consists of an elaborate arrangement of pools and fountains, beyond which are the much more naturalistic Boulder Gardens, littered with massive rocks. Several of the caves found here were also home to reclusive monks, and still bear slight traces of murals, while some of the boulders have been carved into ‘thrones’ which probably had a symbolic religious significance.

School trip to Sigiriya

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Past the Boulder Gardens, steps climb with increasing steepness up to the base of the rock itself. Close to the foot of the rock, a pair of incongruous Victorian metal spiral staircases lead up to the much celebrated Sigiriya Damsels, one of Sri Lanka’s most famous sights: a little picture gallery showing around 20 beautiful bare-breasted nymphs floating on a sea of clouds. Immediately past the damsels, the pathway up the rock is flanked by the Mirror Wall, whose brightly polished surface is inscribed with hundreds of ancient graffiti messages recording early visitors’ impressions of the site – and the nearby damsels in particular. Many are of considerable poetic value, and an important source for historians of Sinhalese language and script.

Sigiriya Damsel

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Further steps lead onwards and upwards to the Lion Platform, embellished with two enormous stone paws, all that remains of the open-mouthed lion which originally guarded the final ascent to the summit of the rock and Kassapa’s palace. Metal steps lead between the paws and up to the summit, clinging to the bare rock face (and presenting something of a challenge to sufferers of vertigo). The summit itself is covered in the slight remains of Kassapa’s palace, although the great jumble of brick foundations is difficult to interpret and far less impressive than the stupendous views down over the Water Gardens below and the plains stretching away in every direction.

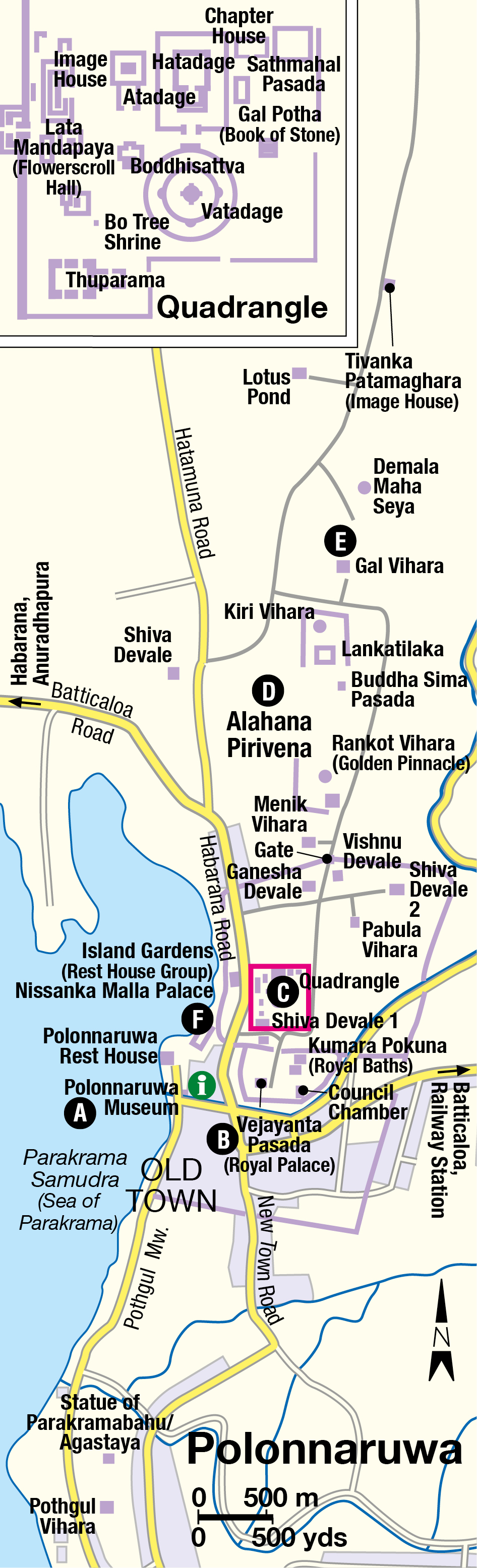

Polonnaruwa

Another of Sri Lanka’s great ruined cities, Polonnaruwa ™ [map] was capital of the island for a far shorter period of time. It enjoyed a brief but exuberant cultural flowering during its 150 years of pre-eminence from 1056 to 1215, during which Sinhalese art and architecture reached new heights of artistry. The ruins (daily 7.30am–6pm; charge) here are more compact, more varied and much more easily digestible than those at Anuradhapura, although it is also more of a museum piece and lacks something of Anuradhapura’s enduring religious vibrancy.

Before entering the site itself, make time for the excellent Polonnaruwa Museum A [map] (daily 9am–5.30pm; charge), the best in the island, with its insightful displays on life in the ancient capital, and some fine exhibits including a number of superb Chola bronzes recovered from the site.

The Citadel

Close to the entrance, the buildings of the Citadel (or Royal Palace Group) comprise the substantial remains of the palace built by the city’s most famous king, Parakramabahu the Great (reigned 1153–86), who was responsible for many of the city’s most impressive structures, though his lust for building and weakness for ill-advised military campaigns almost bankrupted the kingdom. The remains of the Vejayanta Pasada B [map] (Royal Palace) itself are large but rather plain. More impressive is the Council Chamber, the king’s audience hall, whose finely carved base is decorated with dwarfs and galloping elephants and topped with a pair of superb lion statues – the defining symbol of Sinhalese royalty. Just northeast of here, look out for the finely preserved Kumara Pokuna (Royal Baths).

The Vatadage at Polonnaruwa

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The Quadrangle

Contained in a small enclosure just north of the Royal Palace is the remarkable cluster of buildings known as the Quadrangle C [map]. This was the religious heart of the city, home to the famous Tooth Relic (for more information, click here), which was housed here in various temples. The finest of these is the magnificent Vatadage, probably the most beautiful building in Sri Lanka, a glorious circular structure decorated in a riot of carving, with four sumptuous staircases, each embellished with a moonstone, and a makara-decorated balustrade.

Numerous other remains stand cheek-by-jowl around the enclosure. The most obviously impressive is the Thuparama, a solid and unusually well-preserved structure whose exterior carvings show distinct Hindu influence, the result of the powerful coterie of Tamil mercenaries and other Indians who made the city their home. Other notable buildings include the Hatadage, another temple which once housed the Tooth Relic; the uniquely Khmer-style Sathmahal Pasada; the beautiful Lotus Madapa pavilion; and the enormous Gal Potha, a huge rock inscription recording the real and imagined exploits of Nissanka Malla, a famously boastful Polonnaruwan king whose self-glorifying inscriptions can be found all over the city. Immediately south of the Quadrangle is the very Indian-looking Shiva Devale No. 1, one of many Hindu temples at the site, built by the Tamil Pandyans who conquered the city in the 13th century.

Cycle the site

Hiring a bicycle is the most enjoyable way to explore Polonnaruwa. The flat, traffic-free roads through the site make it one of Sri Lanka’s most enjoyable two-wheel experiences.

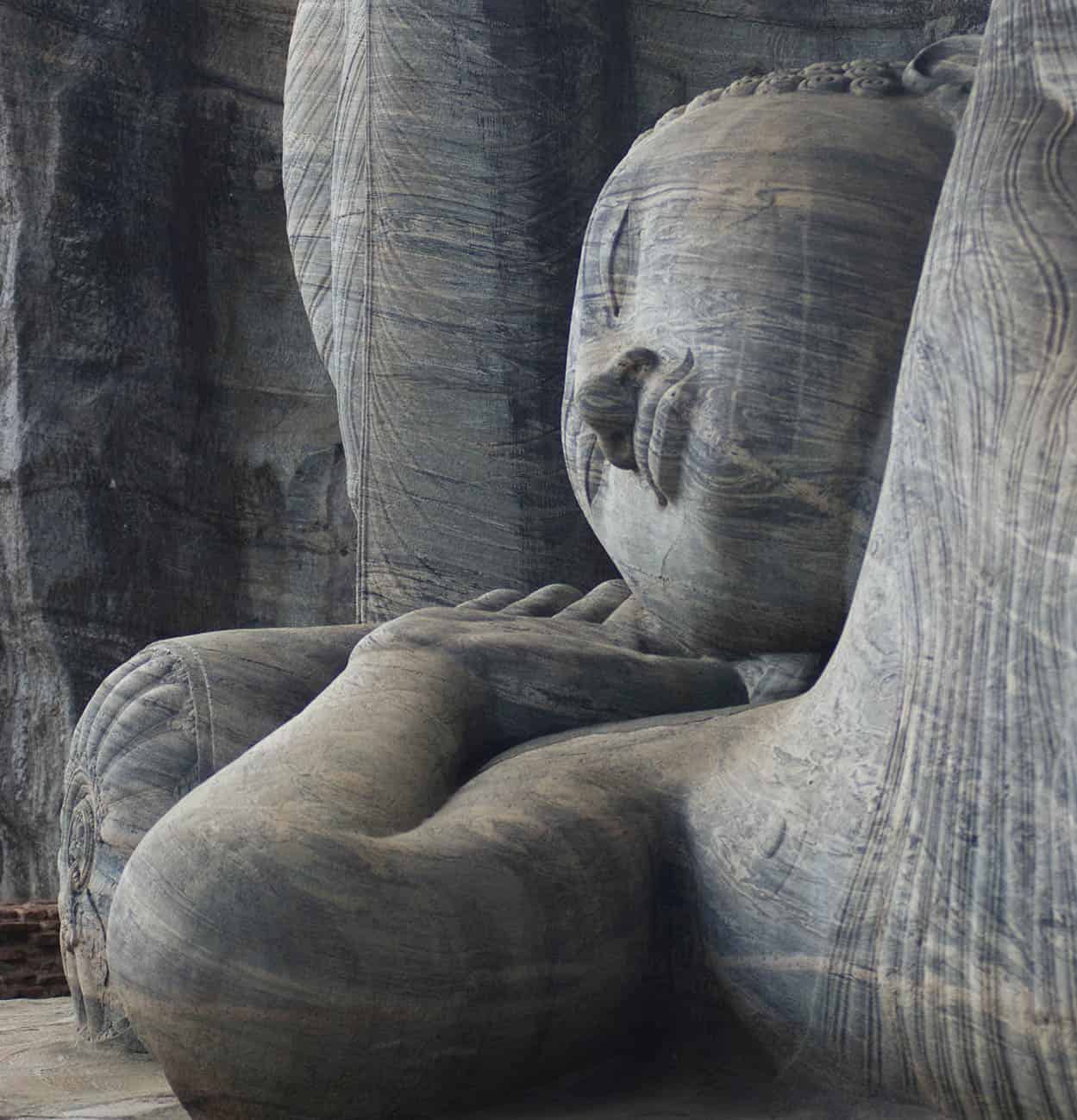

The Alahana Pirivena and Beyond

North of the Quadrangle lie the extensive remains of the Alahana Pirivena D [map], the city’s most important monastery. The first notable sight here is the monumental Rankot Vihara, the only stupa at Polonnaruwa to rival the great examples at Anuradhapura. Continuing north, the heart of the monastery is marked by a cluster of exceptional buildings, including the Lankatilake, a narrow shrine enclosing a huge – though headless – standing Buddha; the Kiri Vihara, a fine, delicately built stupa; and the Buddha Sima Pasada, the monastery’s chapter house. Finest of all, however, is the Gal Vihara E [map], further north, one of the island’s most famous shrines, comprising a line of four monumental stone Buddhas including a vast reclining Buddha, the most famous statue in Sri Lanka, and, next to it, a unique standing figure with arms crossed who is sometimes thought to represent Ananda, the Buddha’s most devoted follower.

Continuing north, you pass the gargantuan Demala Maha Seya stupa, almost buried in vegetation, before reaching the Tivanka Patamaghara, another Buddhist shrine built in a heavily Indianised architectural style, exemplified by the finely carved niched windows which decorate its exterior. Inside, a sequence of outstanding (though difficult to see) frescoes of Hindu-style deities in elaborate tiaras cover the walls.

The enormous reclining Buddha at Gal Vihara

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

The Southern Remains

Further interesting remains lie south of the main site along the shores of the vast Parakrama Samudra, one of the greatest of the enormous artificial lakes, or ‘tanks’, built for irrigation by the ancient Sinhalese (for more information, click here). The so-called Island Gardens F [map] (or Rest House Group), almost in the middle of the little modern town centre, are home to the modest remnants of Nissanka Malla’s palace, while further south lies the Pothgul Vihara, a circular shrine, and the famous statue of a bearded figure holding a palm-leaf manuscript, either a sage or Parakramabahu himself, depending on who you believe.

Minneriya and Kaudulla

If you have had enough of Buddhist remains, a pair of outstanding national parks lie close to Polonnaruwa. Minneriya # [map] and Kaudulla National Parks (both daily; morning safari 5.30-9.30am; evening safari 2.30-6pm; charge) are famous mainly for their extensive elephant populations. The parks form part of an ‘elephant corridor’, and the animals migrate seasonally between the two reserves, depending on water levels in the local tanks (local guides will be able to tell you which of the two parks offers the best elephant-spotting opportunities at any given time).

Elephant in the National Park

Ravindralal Anthonis

Yapahuwa to Ritigala

On the eastern edge of the Cultural Triangle, the ruined citadel of Yapahuwa ¢ [map] (daily 8am–6pm; charge) is all that remains of one of the many short-lived Sinhalese capitals which were established and then abandoned in rapid succession during the chaotic 13th and 14th centuries. The royal palace formerly stood atop the enormous rocky outcrop which forms the centrepiece of the site, although the main attraction is the spectacular stone staircase which climbs up the rock with dizzying steepness, and is sumptuously decorated with statues of elephants, dwarfs, goddesses and a pair of pop-eyed stone lions. The remains of a few other buildings and a small museum stand at the foot of the steps.

Northeast of Yapahuwa is the Aukana Buddha ∞ [map], a 12m (39ft) high statue of a standing Buddha which has become one of Sri Lanka’s most famous icons – a mighty and austerely simple figure, best seen at dawn when the low light reveals the stone’s fine detail (the name Aukana means ‘sun-eating’). Nearby is the equally grand Sasseruwa Buddha, another monumental, if slightly less finely carved, standing figure – although for many visitors the relative lack of sculptural finish makes it the more humanised and endearing of the two colossi.

Abandoned Buddha

A legend states that the Aukana Buddha was carved by a master sculptor and the Sasseruwa Buddha by his apprentice – and that the student, on seeing the excellence of his teacher’s creation, abandoned his own statue in despair.

Continuing northeast you come to the atmospheric forest monastery of Ritigala § [map] (admission with CT ticket), the best known of the various woodland retreats to which the island’s more ascetic monks withdrew in centuries past. The forest monastery was discovered only in 1872. Buried amongst beautiful lowland dry-zone forest, the monastery’s ruins are deeply atmospheric but little understood, consisting of a succession of interlinked courtyards, walkways and the foundations of structures built in a distinctive ‘double-platform’ style, with pairs of buildings surrounded by miniature moats and linked by tiny bridges – although their exact function remains obscure.

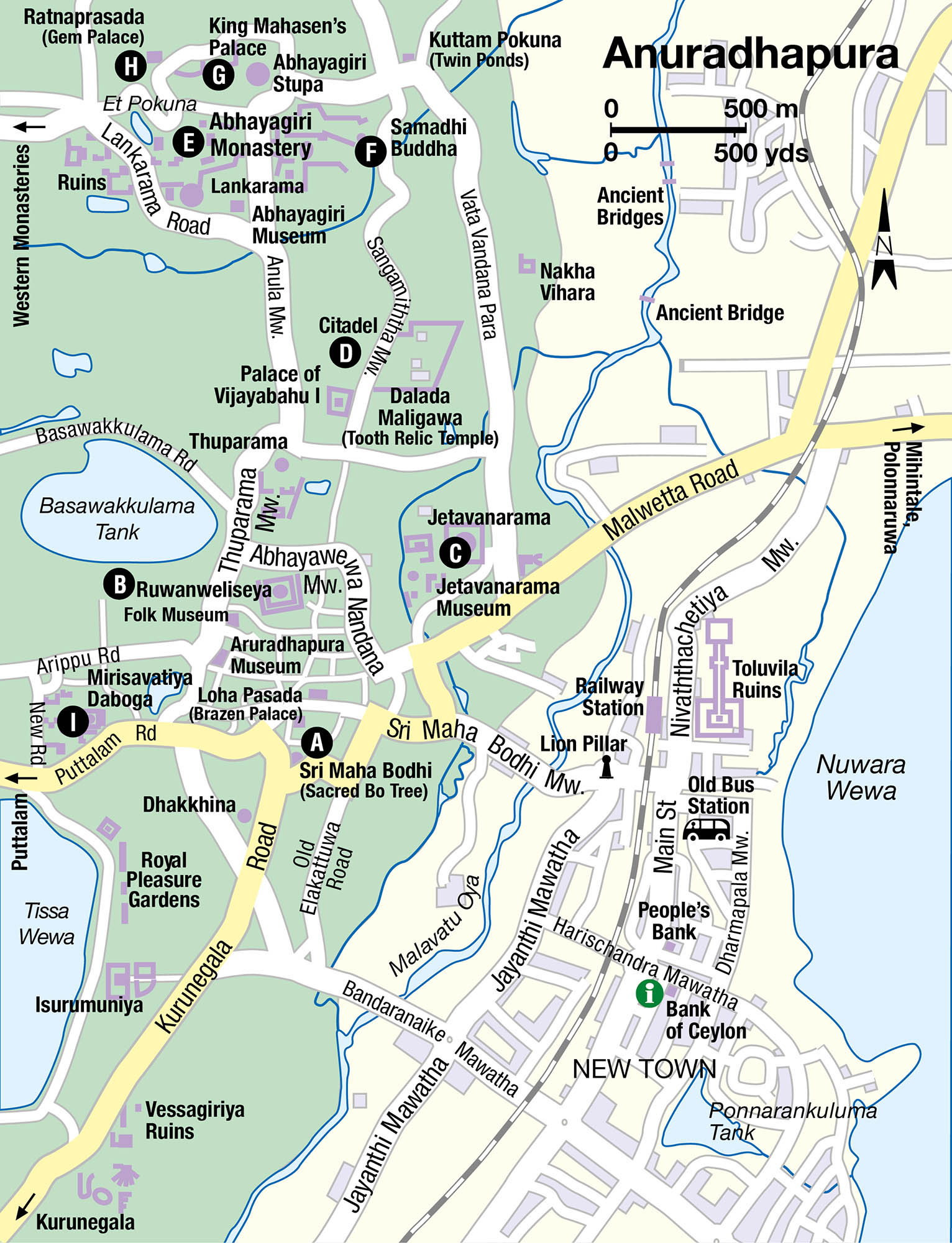

Anuradhapura

At the northern edge of the Cultural Triangle, the great monastic ruined city of Anuradhapura ¶ [map] was for some 1,500 years the island’s capital and cultural fulcrum. One of the greatest monastic cities the world has ever seen, ancient Anuradhapura supported a population of as many as 10,000 monks, and the ruins of its great religious foundations, monumental stupas and enormous man-made lakes continue to inspire awe amongst visitors and pride amongst the island’s latter-day Sinhalese.

The Aukana Buddha near Kekirawa

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Most (but not all) of the main sites in Anuradhapura are contained in the Sacred Precinct, to the west of the modern town of Anuradhapura. The best way to see the sights is to hire a bicycle, although you will need a couple of days just to cover the main attractions, and far longer if you want to really get to understand the vast and often bewildering sprawl of monuments and ruins which dot the countryside in and around the city.

The Mahavihara

At the centre of the Sacred Precinct are the remains of the great Mahavihara monastery, still one of the island’s great pilgrimage centres thanks to the presence here of the Sri Maha Bodhi A [map] (Sacred Bo Tree; donation), a tree of enormous age which was allegedly grown from a cutting from the tree in India under which the Buddha attained enlightenment. The Sri Maha Bodhi is now the focus of worship in Anuradhapura, and always busy with pilgrims and tourists alike.

North of the Sri Maha Bodhi rises the huge, dirty-white hemisphere of the Ruwanweliseya B [map], the third largest – and best-preserved – stupa in the city, standing in a square compound whose flanking walls are decorated with dozens of elephant heads. From here a road runs north to another stupa, the Thuparama, the oldest in the whole of Sri Lanka and a far more modest structure than the Ruwanweliseya, picturesquely framed by a cluster of lopsided columns which once supported a roof.

Irrigation in Ancient Sri Lanka

The trio of lakes which surround Anuradhapura are just three of the thousands of man-made reservoirs – or ‘tanks’ (wewas) – that dot Sri Lanka’s northern plains. Early Sinhalese civilisation was agricultural, and the lack of regular rainfall in the northern dry zone meant that the storage and distribution of water from the region’s few dependable rivers or collected during the brief monsoon, was crucial. The island’s first reservoirs and irrigation channels date from the earliest days of Sinhalese settlement, but it was between the 3rd and 7th centuries AD that the vast system of tanks was linked by thousands of miles of irrigation channels in one of the greatest hydraulic achievements the world has seen. Over time, the maintenance of these systems began to place an untenable burden on the population and as waves of Tamil invaders harassed the north, they felt into disarray. Gradually, the water supply failed and the Sinhalese decamped, abandoning the northern plains and moving towards the less arid lands further south.

The Jetavana Monastery and the Citadel

Another of Anuradhapura’s great monasteries, the Jetavana C [map], lies just under a kilometre northeast of the Mahavihara. Like the Mahavihara, it is centred around a monumental stupa, a colossal brick edifice which once reached a height of 120m (390ft), though it has now been reduced to around 70m (230ft). It remains the world’s largest brick-built structure. The area around the stupa is littered with remains, including a finely preserved bathing pool and the unusual ‘Buddhist railing’, a kind of ancient stone fence. There is also an interesting museum (daily 8.30am–5.30pm; charge) housing an excellent selection of finely crafted items found at the site.

The impressive Jetavana stupa

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

North of the Jetavanarama, the large walled area known as the Citadel D [map] formerly enclosed the city’s royal palace and central commercial district, though little now survives apart from innumerable brick foundations of unidentifiable buildings and the remnants of the Royal Palace itself, notable mainly for the pair of fine guard stones at its entrance, showing a pair of unusually fat dwarves.

The Abhayagiri Monastery

Continuing north you come to the Abhayagiri E [map] monastery, once the largest in Anuradhapura, but now the least visited and therefore most atmospheric area in the city, with a prodigious quantity of foundations, pillars, staircases and eroded brick walls dotted amidst beautiful woodland. Again, a monumental stupa lies at the heart of the monastery. East of the stupa, the famous Samadhi Buddha F [map] statue shows the Buddha deep in meditation – a classic Sri Lankan pose, combining simplicity and serenity. Just beyond here are the marvellously well-preserved Kuttam Pokuna, two bathing pools which were once used for monks’ ritual ablutions.

Further monuments lie scattered in the surrounding woodlands, including Mahasen’s Palace G [map], home to perhaps the finest moonstone in Sri Lanka; the Ratnaprasada H [map], notable for its remarkable guard stone figure; and the gargantuan Et Pokuna, or Elephant Pool, the largest bathing pool in the city, and every bit as big as its name suggests. There’s also a small museum about 500m/yds south of the stupa (daily 8am–5pm; charge) housing a fine collection of statues and other artefacts recovered from the area.

A monk in the shade

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Outlying Remains

A further rewarding clutch of monuments lies south of the Mahavihara, starting with the fine Mirisavatiya Daboga I [map], a large white structure confusingly similar in size and appearance to the nearby Ruwanweliseya, which is famous for having been built by King Dutugemunu out of remorse for having thoughtlessly eaten a bowl of chillies without offering any to the city’s monks. South of here, the picturesque Royal Pleasure Gardens contain two fine bathing pools, one carved with wonderfully naturalistic low-relief elephants. Just beyond is the Isurumuniya Vihara (charge), one of the oldest shrines in the city and home to an interesting selection of carvings.

Steps at Kuttam Pokuna

Sylvaine Poitau/Apa Publications

Mihintale

Twelve kilometres (7 miles) east of Anuradhapura, Mihintale • [map] is revered amongst Sri Lankans as the place at which Buddhism was first introduced to the island. According to legend, it was here that Mahinda, and envoy of the great Indian Buddhist emperor Asoka, converted the Sinhalese king Devanampiya Tissa and his followers in 247BC.

The site is deeply atmospheric, with a sequence of stupas and other remains scattered across a sequence of hilltops linked by beautiful stone stairways and shaded by innumerable frangipani trees.

After the car park, the site museum (closed for renovation) and the ruins of a medieval hospital, stone steps lead up to the remains of the Medamaluwa monastery. The remains include two huge stone troughs which would have originally been filled daily by devotees with rice for the monastery’s monks, and a pair of ancient stone tablets on which are written the rules of monastic life. From here, a long line of steps leads to the centre of Mihintale (charge) and the small Ambasthala Stupa, allegedly marking the exact spot at which Mahinda converted Devanampiya Tissa. Steps lead from here to a cluster of further remains, including the dramatic Aradhana Gala rocky outcrop, from which Mahinda preached his first sermon, and up again to the Mahaseya Stupa, from where there are marvellous views out over the surrounding plains to the great stupas of Anuradhapura, clearly visible in the distance.

Unrequited love

Lover’s Leap was named in honour of a young Dutch lady named Francina van Rhede who, according to tradition, jumped off Swami Rock after having been abandoned by her lover – although colonial records suggest that not only did she survive the fall, but that she also subsequently married someone else.

The East

Sri Lanka’s east is one of the poorest and most sparsely populated regions on the island thanks to its arid climate and inhospitable terrain. The area’s fortunes were further blighted by the civil war, whose fluctuating front line ran through the region and pitted its inhabitants – a varied mix of Tamils, Sinhalese and Muslims – against one another in recurrent bouts of communal blood-letting, and by the Asian tsunami in 2004, which wreaked havoc all along the coast. For the visitor, the region’s major attractions are at present limited to a handful of beaches and the little city of Trincomalee.

Trincomalee

The principal city of the east, Trincomalee ª [map] (or ‘Trinco’), is Sri Lanka’s most ethnically diverse city, its population divided almost equally between Tamils, Sinhalese and Muslims. Repeated clashes between these different ethnic groups made the city the most volatile in the island throughout the civil war, and have continued to overshadow its fortunes during the subsequent ceasefire. Although parts of the city are scruffy and unappealing, its magnificent natural setting and faded colonial atmosphere lend it an understated but palpable charm.

Trinco’s most interesting area, occupying a narrow promontory dividing Dutch and Back bays, is Fort Frederick, the old British fort, surrounded by substantial ramparts enclosing a tranquil stretch of parkland dotted with 19th-century colonial buildings. Entering through the impressive main gate, a road winds up through the fort to Swami Rock, a dramatic cliff top rising high at the edge of the promontory above deep-blue waters, with fine views over Back Bay, the town, and the innumerable fishing boats bobbing in the waters below. Perched atop Swami Rock, the Koneswaram Kovil is one of the island’s holiest Shiva temples, although the building itself is modern and of little interest. Immediately behind the temple, the sheer cliff plunges into the waters at Lover’s Leap.

Lover’s Leap on the Swami Rock

Apa Publications

Below Swami Rock, the town centre comprises a dusty grid of low-rise streets dotted with colourful little Hindu temples, with pleasant backstreets of decaying colonial villas. At the southeastern end of the centre, the dusty open space of the Esplanade backs the attractive town beach flanking Dutch Bay. Walking across the town centre brings you to Inner Harbour, the original source of the city’s maritime prosperity and importance and still a grand sight, with large container ships and tanks moored in the distance and lines of hills beyond.

East coast beach

Apa Publications

Uppuveli and Nilaveli

Most visitors come to the Trincomalee area to visit the twin resorts of Uppuveli and Nilaveli, lying on a swathe of beautiful golden sand a few kilometres north of the city. Despite repeated upheavals during the civil war and, more recently, significant tsunami damage, both resorts have somehow kept going against the odds, embodying the sense of enduring optimism which characterises life in the war-torn east and north. Development is at present confined to a couple of large resort hotels and a cluster of low-key guesthouses, and the atmosphere is thoroughly somnolent. Uppuveli is also the jumping-off point for boat and snorkelling trips to nearby Pigeon Island, which boasts colourful tropical fish and patches of live coral.

Arugam Bay and Around

The east’s most popular tourist destination, the village of Arugam Bay q [map] is best known for its superb surf. The waves here are the finest on the island, attracting a steady stream of die-hard wave-chasers. The real attraction is the village’s laid-back and friendly atmosphere, its simple way of life, and perhaps best of all, the wonderful feeling of being a long way from anywhere else.

Palm trees line the coast

Apa Publications

There is a range of interesting excursions on offer here, including boat trips to the nearby Pottuvil Lagoon, ‘sea safaris’ in search of dolphins and other marine life and cycling tours of local villages.

Around 15km (9 miles) down the main road heading inland from Arugam Bay is the small but beautiful Lahugala National Park (daily 6.30am–6.30pm; charge), and the scenic tropical dry forest that surrounds it. Lahugala is home to a large number of elephants, which congregate around the picturesque Lahugala Tank.

The North

The north is Sri Lanka’s least known and least developed region. Out of bounds during the two decades of civil war, the area is only gradually reopening to visitors after the end of the civil war in 2009 and remains almost completely untouched by modern tourism. Not that the region is without attractions. Home to an almost exclusively Tamil population, the north is quite unlike the rest of Sri Lanka, and its long history has blended Hindu, Christian and colonial traditions into a unique whole.

Jaffna

For visitors accustomed to the Sinhalese south, the historic old Tamil city of Jaffna w [map] offers an entirely different perspective on Sri Lanka. The crucible of Tamil culture on the island, the city looks for inspiration as much to India, a short distance north over the Palk Straits, as to Colombo, and retains a character quite different from that in the rest of the island. Repeatedly besieged and fought over during the civil war, parts of Jaffna still bear the signs of conflict, most notably in the area around the huge Dutch fort, the largest in Asia. Much of the city, however, has survived surprisingly intact. The town centre remains vibrant and colourful, dotted with expansive Hindu temples and huge churches, and in the suburbs, decaying old Dutch villas still line the sedate, tree-lined streets. On the northern edge of town, the majestic Nallur Kandaswamy Temple is the most majestic Hindu temple in Sri Lanka, and the only one which rivals the great temples of India in size and in the intensity of its religious rituals and festivals.

Jaffna street scene

Apa Publications

The Jaffna Peninsula and Islands