CHAPTER 5

“Keep yelling, young un”

Mrs. Hogget shook her head at least a dozen times.

“For the life of me I can’t see why you do let that pig run all over the place like you do, round and round the yard he do go, chasing my ducks about, shoving his nose into everything, shouldn’t wonder but what he’ll be out with you and Fly moving the sheep about afore long, why don’t you shut him up, he’s running all his flesh off, he won’t never be fit for Christmas, Easter more like, what d’you call him?”

“Just Pig,” said Farmer Hogget.

A month had gone by since the Village Fair, a month in which a lot of interesting things had happened to Babe. The fact that perhaps most concerned his future, though he did not know it, was that Farmer Hogget had become fond of him. He liked to see the piglet pottering happily about the yard with Fly, keeping out of mischief, as far as he could tell, if you didn’t count moving the ducks around. He did this now with a good deal of skill, the farmer noticed, even to the extent of being able, once, to separate the white ducks from the brown, though that must just have been a fluke. The more he thought of it, the less Farmer Hogget liked the idea of butchering Pig.

The other developments were in Babe’s education. Despite herself, Fly found that she took pleasure and pride in teaching him the ways of the sheepdog, though she knew that of course he would never be fast enough to work sheep. Anyway the boss would never let him try.

As for Ma, she was back with the flock, her foot healed, her cough better. But all the time that she had been shut in the box, Babe had spent every moment that Fly was out of the stables chatting to the old ewe. Already he understood, in a way that Fly never could, the sheep’s point of view. He longed to meet the flock, to be introduced. He thought it would be extremely interesting.

“D’you think I could, Ma?” he had said.

“Could what, young un?”

“Well, come and visit you, when you go back to your friends?”

“Oh ar. You could do, easy enough. You only got to go through the bottom gate and up the hill to the big field by the lane. Don’t know what the farmer’d say though. Or that wolf.”

Once Fly had slipped quietly in and found him perched on the straw stack.

“Babe!” she had said sharply. “You’re not talking to that stupid thing, are you?”

“Well, yes, Mum, I was.”

“Save your breath, dear. It won’t understand a word you say.”

“Bah!” said Ma.

For a moment Babe was tempted to tell his foster mother what he had in mind, but something told him to keep quiet. Instead he made a plan. He would wait for two things to happen. First, for Ma to rejoin the flock. And, after that, for market day, when both the boss and his mum would be out of the way. Then he would go up the hill.

Towards the end of the very next week the two things had happened. Ma had been turned out, and a couple of days after that Babe watched as Fly jumped into the back of the Land Rover, and it drove out of the yard and away.

Babe’s were not the only eyes that watched its departure. At the top of the hill a cattle truck stood half-hidden under a clump of trees at the side of the lane. As soon as the Land Rover had disappeared from sight along the road to the market town, a man jumped hurriedly out and opened the gate into the field. Another backed the truck into the gateway.

Babe meanwhile was trotting excitedly up the hill to pay his visit to the flock. He came to the gate at the bottom of the field and squeezed under it. The field was steep and curved, and at first he could not see a single sheep. But then he heard a distant drumming of hooves and suddenly the whole flock came galloping over the brow of the hill and down toward him. Around them ran two strange collies, lean silent dogs that seemed to flow effortlessly over the grass. From high above came the sound of a thin whistle, and in easy partnership the dogs swept around the sheep, and began to drive them back up the slope.

Despite himself, Babe was caught up in the press of jostling bleating animals and carried along with them. Around him rose a chorus of panting protesting voices, some shrill, some hoarse, some deep and guttural, but all saying the same thing.

“Wolf! Wolf!” cried the flock in dazed confusion.

Small by comparison and short in the leg, Babe soon fell behind the main body, and as they reached the top of the hill he found himself right at the back in company with an old sheep who cried “Wolf!” more loudly than any.

“Ma!” he cried breathlessly. “It’s you!”

Behind them one dog lay down at a whistle, and in front the flock checked as the other dog steadied them. In the corner of the field the tailgate and wings of the cattle truck filled the gateway, and the two men waited, sticks and arms outspread.

“Oh hullo, young un,” puffed the old sheep. “Fine day you chose to come, I’ll say.”

“What is it? What’s happening? Who are these men?” asked Babe.

“Rustlers,” said Ma. “They’m sheep rustlers.”

“What d’you mean?”

“Thieves, young un, that’s what I do mean. Sheep stealers. We’ll all be in that truck afore you can blink your eye.”

“What can we do?”

“Do? Ain’t nothing we can do, unless we can slip past this here wolf.”

She made as if to escape, but the dog behind darted in, and she turned back.

Again, one of the men whistled, and the dog pressed. Gradually, held against the headland of the field by the second dog and the men, the flock began to move forward. Already the leaders were nearing the tailgate of the truck.

“We’m beat,” said Ma mournfully. “You run for it, young un.” I will, thought Babe, but not the way you mean. Little as he was, he felt suddenly not fear but anger, furious anger that the boss’s sheep were being stolen. My mum’s not here to protect them so I must, he said to himself bravely, and he ran quickly around the hedge side of the flock, and jumping onto the bottom of the tailgate, turned to face them.

“Please!” he cried. “I beg you! Please don’t come any closer. If you would be so kind, dear sensible sheep!”

His unexpected appearance had a number of immediate effects. The shock of being so politely addressed stopped the flock in its tracks, and the cries of “Wolf!” changed to murmurs of “In’t he lovely!” and “Proper little gennulman!” Ma had told them something of her new friend, and now to see him in the flesh and to hear his well-chosen words released them from the dominance of the dogs. They began to fidget and look about for an escape route. This was opened for them when the men (cursing quietly, for above all things they were anxious to avoid too much noise) sent the flanking dog to drive the pig away, and some of the sheep began to slip past them.

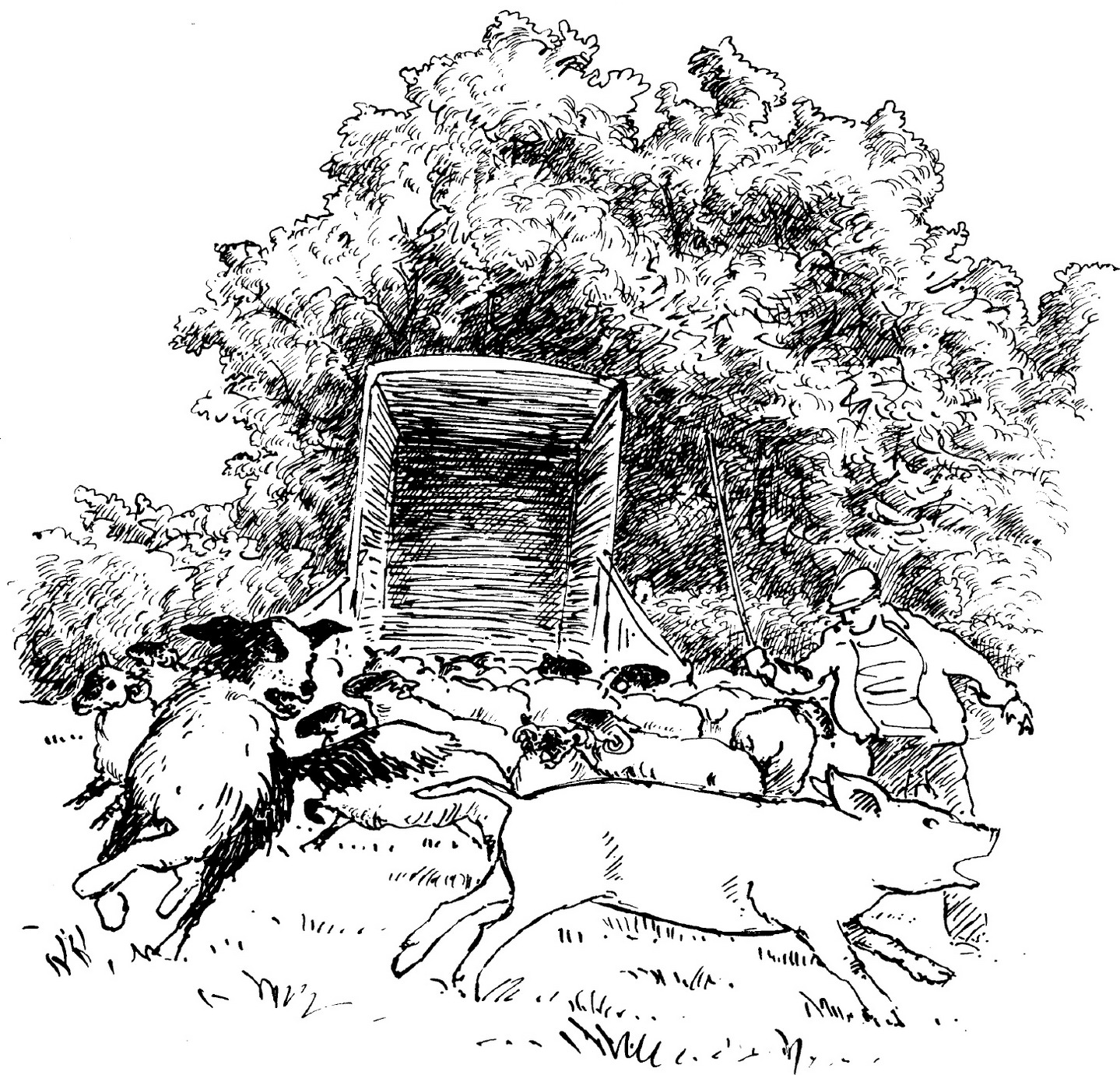

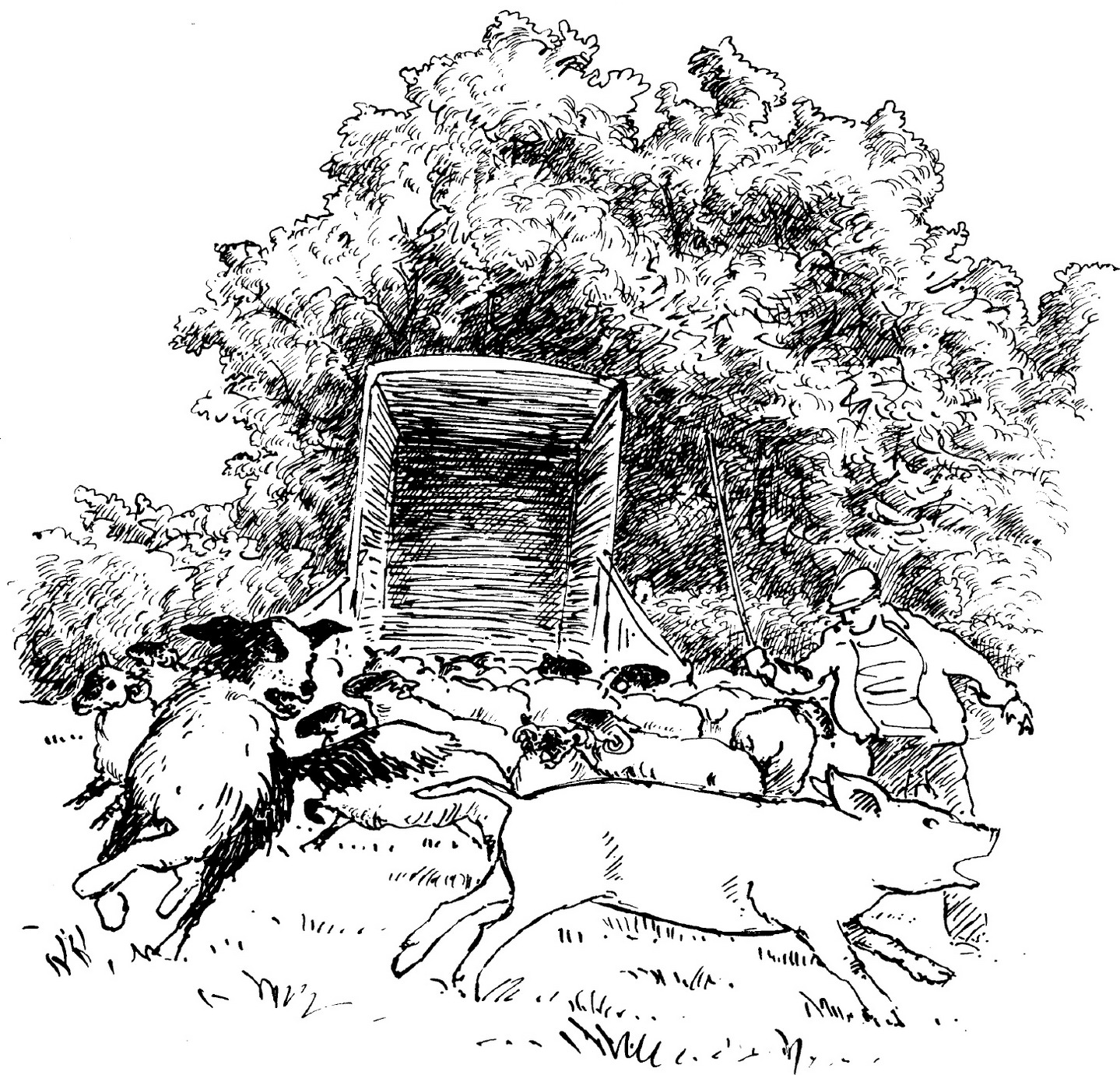

Next moment all was chaos. Angrily the dog ran at Babe, who scuttled away squealing at the top of his voice in a mixture of fright and fury. The men closed on him, sticks raised. Desperately he shot between the legs of one, who fell with a crash, while the other, striking out madly, hit the rearguard dog as it came to help, and sent it yowling. In half a minute the carefully planned raid was ruined, as the sheep scattered everywhere.

“Keep yelling, young un!” bawled Ma, as she ran beside Babe. “They won’t never stay here with that row going on!”

And suddenly all sorts of things began to happen as those deafening squeals rang out over the quiet countryside. Birds flew startled from the trees, cows in nearby fields began to gallop about, dogs in distant farms to bark, passing motorists to stop and stare. In the farmhouse below Mrs. Hogget heard the noise as she had on the day of the Fair. She stuck her head out the window and saw the rustlers, their truck, galloping sheep, and Babe. She dialled 999 but then talked for so long that by the time a patrol car drove up the lane, the rustlers had long gone. Snarling at each other and their dogs, they had driven hurriedly away with not one single sheep to show for their pains.

“You won’t never believe it!” cried Mrs. Hogget when her husband returned from market. “But we’ve had rustlers, just after you’d gone it were, come with a huge cattle truck they did, the police said, they seen the tire marks in the gateway, and a chap in a car seen the truck go by in a hurry, and there’s been a lot of it about, and he give the alarm, he did, kept screaming and shrieking enough to bust your eardrums, we should have lost every sheep on the place if ’tweren’t for him, ’tis him we’ve got to thank.”

“Who?” said Farmer Hogget.

“Him!” said his wife, pointing at Babe who was telling Fly all about it. “Don’t ask me how he got there or why he done it, all I knows is he saved our bacon and now I’m going to save his, he’s staying with us just like another dog, don’t care if he gets as big as a house, because if you think I’m going to stand by and see him butchered after what he done for us today, you’ve got another think coming, what d’you say to that?”

A slow smile spread over Farmer Hogget’s long face.