CHAPTER 12

“That’ll do”

Hundreds of thousands of pairs of eyes watched that first dog, but none more keenly than those of Hogget, Fly, and Babe.

The car-park was a big sloping field overlooking the course, and the farmer had driven the Land Rover to the topmost corner, well away from other cars. From inside, the three so different faces watched intently.

Conditions, Hogget could see immediately, were very difficult. In addition to the driving rain, which made the going slippery and the sheep more obstinate than usual, there was quite a strong wind blowing almost directly from the Holding Post back toward the handler, and the dog was finding it hard to hear commands.

The more anxious the dog was, the more the sheep tried to break from him, and thus the angrier he became. It was a vicious circle, and when at last the ten sheep were penned and the handler pulled the gate shut and cried “That’ll do!” no one was surprised that they had scored no more than seventy points out of a possible hundred.

So it went on. Man after man came to stand beside the great sarsen stone, men from the North and from the West, from Scotland, and Wales, and Ireland, with dogs and bitches, large and small, rough-coated and smooth, black-and-white or gray or brown or blue merle. Some fared better than others of course, were steadier on their sheep or had steadier sheep to deal with. But still, as Farmer Hogget’s turn drew near (as luck would have it, he was last to go), there was no score higher than eighty-five.

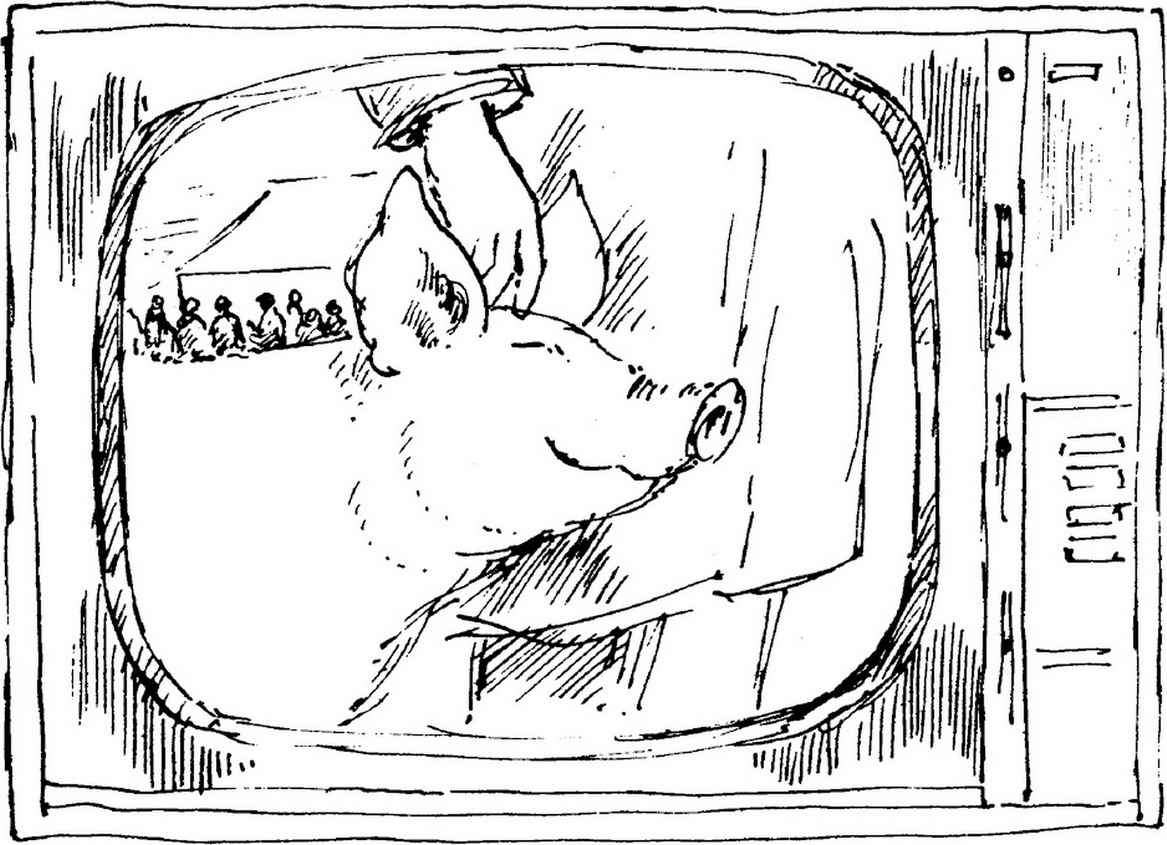

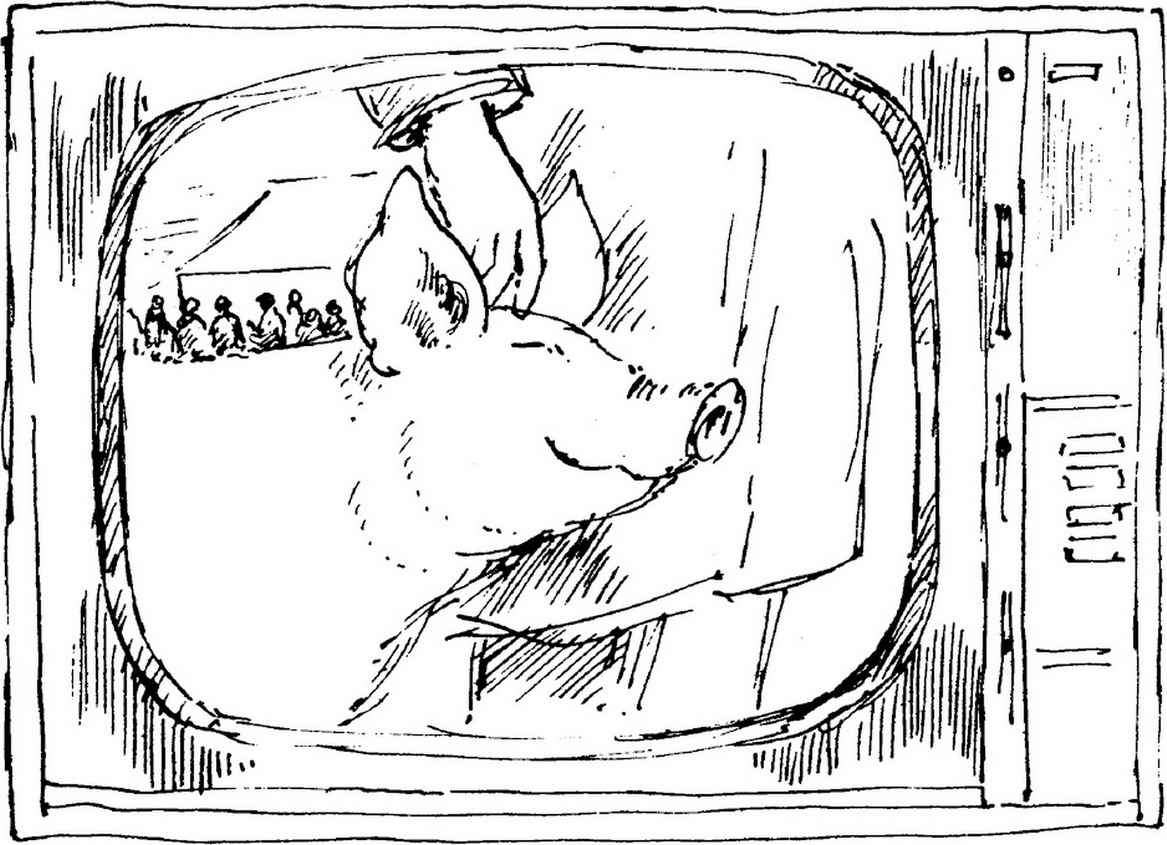

At home Mrs. Hogget chanced to turn the sound of the television back up in time to hear the commentator confirm this.

“One more to go,” he said, “and the target to beat is eighty-five points, set by Mr. Jones from Wales and his dog Bryn, a very creditable total considering the appalling weather conditions we have up here today. It’s very hard to imagine that score being beaten, but here comes the last competitor to try and do just that,” and suddenly there appeared on the screen before Mrs. Hogget’s eyes the tall long-striding figure of her husband, walking out toward the great stone with tubby old Fly at his heels.

“This is Mr. Hogget with Pig,” said the commentator. “A bit of a strange name that, but then I must say his dog’s rather on the fat side…hullo, he’s sending the dog back…what on earth?…oh, good heavens!…Will you look at that!”

And as Mrs. Hogget and hundreds of thousands of other viewers looked, they saw Fly go trotting back toward the car-park.

And from it, cantering through the continuing rain, came the long, lean, beautifully clean figure of a Large White pig.

Straight to Hogget’s side ran Babe, and stood like a statue, his great ears fanned, his little eyes fixed upon the distant sheep.

At home, Mrs. Hogget’s mouth opened wide, but for once no sound came from it.

On the course, there was a moment of stunned silence and then a great burst of noise.

On the screen, the cameras showed every aspect of the amazing scene—the spectators pointing, gaping, grinning; the red-faced judges hastily conferring; Hogget and Babe waiting patiently; and finally the commentator.

“This is really quite ridiculous,” he said with a shamefaced smile, “but in point of fact there seems to be nothing in the rule book that says that only sheepdogs may compete. So it looks as though the judges are bound to allow Mr. Hogget to run this, er, sheep-pig I suppose we’ll have to call it, ha, ha! One look at it, and the sheep will disappear into the next county without a doubt! Still, we might as well end the day with a good laugh!”

And indeed at that moment a great gale of laughter arose, as Hogget, receiving a most unwilling nod from the judges, said quietly, “Away to me, Pig,” and Babe began his outrun to the right.

How they roared at the mere sight of him running (though many noticed how fast he went), and at the purely crazy thought of a pig herding sheep, and especially at the way he squealed and squealed at the top of his voice, in foolish excitement they supposed.

But though he was excited, tremendously excited at the thrill of actually competing in the Grand Challenge Sheepdog Trials, Babe was nobody’s fool. He was yelling out the password: “I may be ewe, I may be ram, I may be mutton, may be lamb, but on the hoof or on the hook, I bain’t so stupid as I look,” as he ran.

This was the danger point—before he’d met his sheep—and again and again he repeated the magic words, shouting above the noise of wind and rain, his eyes fixed on the ten sheep by the Holding Post. Their eyes were just as fixed on him, eyes that bulged at the sight of this great strange animal approaching, but they held steady, and the now distant crowd fell suddenly silent as they saw the pig take up a perfect position behind his sheep, and heard the astonished judges award ten points for a faultless outrun.

Just for luck, in case they hadn’t believed their ears, Babe gave the password one last time. “…I bain’t so stupid as I look,” he panted, “and a very good afternoon to you all, and I do apologize for having to ask you to work in this miserable weather, I hope you’ll forgive me?”

At once, as he had hoped, there was a positive babble of voices.

“Fancy him knowing the pa-a-a-a-a-assword!”

“What lovely ma-a-a-a-anners!”

“Not like them na-a-a-a-asty wolves!”

“What d’you want us to do, young ma-a-a-a-aster?”

Quickly, for he was conscious that time was ticking away, Babe, first asking politely for their attention, outlined the course to them.

“And I would be really most awfully grateful,” he said, “if you would all bear these points in mind. Keep tightly together, go at a good steady pace, not too fast, not too slow, and walk exactly through the middle of each of the three gates, if you’d be good enough. The moment I enter the shedding ring, would the four of you who are wearing collars (how nice they look, by the way) please walk out of it. And then if you’d all kindly go straight into the final pen, I should be so much obliged.”

All this talk took quite a time, and the crowd and the judges and Mrs. Hogget and her hundreds of thousands of fellow-viewers began to feel that nothing else was going to happen, that the sheep were never going to move, that the whole thing was a stupid farce, a silly joke that had fallen flat.

Only Hogget, standing silent in the rain beside the sarsen stone, had complete confidence in the skills of the sheep-pig.

And suddenly the miracle began to happen.

Marching two by two, as steady as guardsmen on parade, the ten sheep set off for the Fetch Gates, Babe a few paces behind them, silent, powerful, confident. Straight as a die they went toward the distant Hogget, straight between the exact center of the Fetch Gates, without a moment’s hesitation, without deviating an inch from their unswerving course. Hogget said nothing, made no sign, gave no whistle, did not move as the sheep rounded him so closely as almost to brush his boots, and, the Fetch completed, set off for the Drive Away Gates. Once again, their pace never changing, looking neither to left nor to right, keeping so tight a formation that you could have dropped a big tablecloth over the lot, they passed through the precise middle of the Drive Away Gates, and turned as one animal to face the Cross Drive Gates.

It was just the same here. The sheep passed through perfectly and wheeled for the Shedding Ring, while all the time the judges’ scorecards showed maximum points and the crowd watched in a kind of hypnotized hush, whispering to one another for fear of breaking the spell.

“He’s not put a foot wrong!”

“Bang through the middle of every gate.”

“Lovely steady pace.”

“And the handler, he’s not said a word, not even moved, just stood there leaning on his stick.”

“Ah, but he’ll have to move now—you’re never going to tell me that pig can shed four sheep out of the ten on his own!”

The Shedding Ring was a circle perhaps forty yards in diameter, marked out by little heaps of sawdust, and into it the sheep walked, still calm, still collected, and stood waiting.

Outside the circle Babe waited, his eyes on Hogget.

The crowd waited.

Mrs. Hogget waited.

Hundreds of thousands of viewers waited.

Then, just as it seemed nothing more would happen, that the man had somehow lost control of the sheep-pig, that the sheep-pig had lost interest in his sheep, Farmer Hogget raised his stick and with it gave one sharp tap upon the great sarsen stone, a tap that sounded like a pistol shot in the tense atmosphere.

And at this signal Babe walked gently into the circle and up to his sheep.

“Beautifully done,” he said to them quietly, “I can’t tell you how grateful I am to you all. Now, if the four ladies with collars would kindly walk out of the ring when I give a grunt, I should be so much obliged. Then if you would all be good enough to wait until my boss has walked across to the final collecting pen over there and opened its gate, all that remains for you to do is to pop in. Would you do that? Please?”

“A-a-a-a-a-a-ar,” they said softly, and as Babe gave one deep grunt the four collared sheep detached themselves from their companions and calmly, unhurriedly, walked out of the Shedding Ring.

Unmoving, held by the magic of the moment, the crowd watched with no sound but a great sigh of amazement. No one could quite believe his eyes. No one seemed to notice that the wind had dropped and the rain had stopped. No one was surprised when a single shaft of sunshine came suddenly through a hole in the gray clouds and shone full upon the great sarsen stone. Slowly, with his long strides, Hogget left it and walked to the little enclosure of hurdles, the final test of his shepherding. He opened its’ gate and stood, silent still, while the shed animals walked back into the ring to rejoin the rest.

Then he nodded once at Babe, no more, and steadily, smartly, straightly, the ten sheep, with the sheep-pig at their heels, marched into the final pen, and Hogget closed the gate.

As he dropped the loop of rope over the hurdle stake, everyone could see the judges’ marks.

A hundred out of a hundred, the perfect performance, never before reached by man and dog in the whole history of sheepdog trials, but now achieved by man and pig, and everyone went mad!

At home Mrs. Hogget erupted, like a volcano, into a great lava flow of words, pouring them out toward the two figures held by the camera, as though they were actually inside that box in the corner of her sitting room, cheering them, praising them, congratulating first one and then the other, telling them how proud she was, to hurry home, not to be late for supper, it was shepherd’s pie.

As for the crowd of spectators at the Grand Challenge Sheepdog Trials they shouted and yelled and waved their arms and jumped about, while the astonished judges scratched their heads and the amazed competitors shook theirs in wondering disbelief.

“Marvelous! Ma-a-a-a-a-a-arvelous!” bleated the ten penned sheep. And from the back of an ancient Land Rover at the top of the car-park a tubby old black-and-white collie bitch, her plumed tail wagging wildly, barked and barked and barked for joy.

In all the hubbub of noise and excitement, two figures still stood silently side by side.

Then Hogget bent, and gently scratching Babe between his great ears, uttered those words that every handler always says to his working companion when the job is finally done.

Perhaps no one else heard the words, but if they did, there was no doubting the truth of them.

“That’ll do,” said Farmer Hogget to his sheep-pig. “That’ll do.”