3 They Will Not Fight in the Open:

Strategies of Resistance in the Jim Crow Era

“Got one mind for white folks to see / ‘Nother for what I know is me,” went a song that was well known among black southerners in the Jim Crow era.1 Behind the mask of subservience and acceptance of the social order that many black people presented to the world lay a clandestine culture of resistance. In their music, folklore, religion, and value systems, African Americans in the rural South analyzed their world and critiqued the economic and political systems that kept most of them in poverty. At the same time, black individuals and communities adopted a variety of methods to undermine white people's efforts to keep them powerless and poor. That these forms of resistance were usually subtle or ineffective does not mean that they were unimportant. Many of the concerns that motivated organized political activity were also reflected in less obvious, “infrapolitical” strategies that black people employed to challenge their oppression during this period.

This chapter outlines the ways rural black Louisianans quietly struggled to gain economic opportunity, education, political power, and safety from violence in the Jim Crow era. Although these activities did not directly confront white supremacy and affected the social order only slightly, they reflected participants’ awareness of the sources of their oppression and provided the foundations of the twentieth-century freedom struggle. The goals and themes established by informal resistance carried over into the attempts at collective action discussed in later chapters of this book.

No movement to overthrow white supremacy could have emerged in the twentieth century if large numbers of black people had not believed that the system was unjust. Criticisms of the social order usually were not expressed openly for fear of reprisals, but they permeate the songs, stories, and jokes collected by students of black culture and folklore in the twentieth century. Had Louisiana sugar planters listened carefully to the verses sung by their black field hands, they might have detected a reproachful assessment of the economic arrangements that transferred most of the profits from black people's labor to white people who had done little to deserve them. Cane cutters frequently swung their knives to a work song containing these lyrics:

White folks want de niggers to work and sweat

Wants dem to cut de cane till dey is wringin’ wet

We poor niggers gits nothin’ atall

White boss cusses and gits it all.2

Visiting the state in the 1930s, black writer Zora Neale Hurston heard a similar complaint from a friend who told her a folk tale ending with the rhyme, “ought's a ought, figger's a figger; all for de white man, none for the nigger.” As Lawrence Levine has noted, music and storytelling provided forums for protest and social criticism when the usual avenues for political expression had been closed to black southerners.3

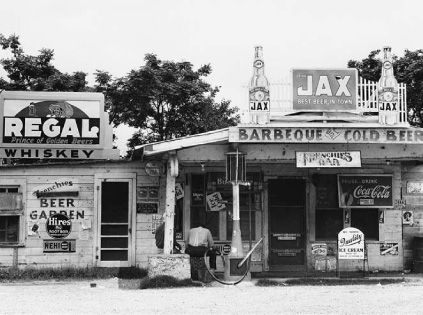

African American blues musicians drew on these cultural traditions to create one of the most important forms of creative expression to emerge within the United States in modern times. Historians of the blues have traced its origins to the plantation regions of the Deep South in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, just when the gains of Reconstruction were being negated by segregation, disfranchisement, and narrowing economic opportunities for African Americans. The distinctive, melancholy sounds of blues harmonicas, guitars, and voices, along with lyrical themes expressing sadness, anger, loss, and betrayal provided the sound-track to the period commonly referred to as the “nadir” of African American history. J. D. Miller, a record company owner who worked with local musicians in the Baton Rouge area in the 1940s, described some of the influences that shaped the songs of many artists that he recorded when he spoke to an interviewer about Lightnin’ Slim (Otis Hicks). “His father was a tenant farmer,” Miller explained, “and they lived out there in the country and after the men would get through work they used to sit out and they'd start playin’ and singin’ you know. And they'd sing these ole blues and the blues was generally bad luck and the troubles they have had.” Other Louisiana musicians grew up listening and playing at juke joints that catered to workers in the state's lumber and turpentine camps, traveling the “barrelhouse circuit” from tiny town to tiny town along a well-worn route from Alabama to Texas.4

Bluesmen and women took their experiences of oppression and turned them into art. Though some listeners found these tunes depressing and fatalistic, for others the blues offered comfort, inspiration, and hope. In rundown shacks and makeshift bars, black workers gathered on Friday and Saturday nights to drink, socialize, play music, sing, and dance, enjoying brief moments of relief from the hard, physical labor that filled most of their days. Such activities were central elements in the lives of many rural black people, despite the disapproval that was occasionally expressed by more upright, churchgoing African Americans in their communities. For some black people, religion and the blues were not so far apart. Of church services, blues player Willie Thomas noted, “They sing: Lord—have mercy . . . / Lord—have mercy . . . ooooh, / Lord—have mercy . . . save poor me. He's in the church singin’ that! He got the blues in church!”5

In many ways, churches and juke joints served similar functions. Both offered respite from the harsh realities of daily life, provided sustenance for the soul, and fostered a sense of community among people who shared the same problems and experiences. Both were spaces where black people asserted that they were more than just bodies forced to labor for others, and where they created distinct cultural and value systems away from the influence of white people.6 For Willie Thomas, the music was something that African Americans could own, in a world where most forms of opportunity and property were denied them. He explained: “The white man could get education and he could learn to read a note, and the Negro couldn't. All he had to get for his music what God give him in his heart. And that's the only thing he got. And he didn't get that from the white man; God give it to him.”7

The blues were an important form of self-expression that helped black people endure oppression and hardship. For those musicians who were fortunate enough to make a living from their art, playing the blues also offered more material benefits. Traveling entertainers enjoyed a greater degree of mobility, autonomy, and creativity than most African Americans in the early twentieth century. Some chose this profession precisely because it offered an alternative to economic exploitation and tight control by white employers. In the 1930s wandering minstrel Carolina Slim justified his rootless existence to a group of Louisiana folklorists by singing them a song that ended:

Bar and juke joint, Melrose, Louisiana, June 1940. Many rural black people gathered in establishments like this one on Friday and Saturday nights to drink, socialize, listen to music, and dance. These pursuits offered a brief respite each week from the hard labor that filled their days. LC-USF34-54355-D, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The boys in Noo ’Leans they oughta be dead

They go to work for fish and bread.

. . . And I ain't bluffin’,

I ain't gonna work for nothin’.8

Similarly, blues musician Black Ace (B. K. Turner) remembered the lucrative career he made out of playing at house parties in Shreveport during the depression. “I couldn't get a li'l job nowhere,” he explained. “So I would go aroun’ play at house parties with this boy—make a dollar-an'-a-half whilst other folks was gettin’ that for one day's work on relief. . . . I get three or four parties, man—I made a lot of money. . . . Dollar-an'-a-half for fun!”9

African Americans who managed to evade plantation labor and other low-paid jobs were in the minority. Yet many others sought to improve their economic positions in whatever ways they could. Thousands of agricultural workers left their employers at the end of each year in search of higher wages and better treatment.10 To the chagrin of plantation owners, some of them did not even wait that long, preferring to abandon their crops before harvest time rather than endure beatings or face the probability of coming out in debt. Planters complained that black sharecroppers and laborers were “always dissatisfied and moving from one place to another,” often attributing this to their supposedly inherent shiftlessness and unreliability.11 Contrary to white people's assumptions, black workers’ peripatetic tendencies were not random or unpurposeful. The statement given by sharecropper John Pickering to a notary public in Texas after he moved there from Louisiana in 1926 shows that his decision resulted from a carefully considered, accurate analysis of the plantation system and his chances of making a living if he had stayed with his previous employer. “I moved off of the place of the said William Wilson because he would not give me a fair settlement on what I had made and what I earned and would not account to me for my share of the cotton crop,” Pickering said. “I being an ignorant negro he would not furnish me with a statement showing what the cotton sold for and what goods I had procured from him, but insisted that, notwithstanding his getting all the cotton, I still owed him three hundred dollars. When I found out he would not give me a fair settlement and was getting all of my earnings, I decided to move into the State of Texas because I knew that in the State of Louisiana the big planters buy and sell negroes and never let one get out of debt.”12

Many other black people shared Pickering's views. Harrison Brown believed that white people aimed to maintain the supply of “free” (meaning unpaid) labor that they had enjoyed before the Civil War. Outlining the difficulties sharecroppers faced in finding good landlords or saving enough money to buy land of their own, he stated, “We mostly had to do their work, you know. . . . They didn't intend for you to get out.” Describing conditions in Bossier Parish in the 1920s, cotton farmer W. C. Brown wrote, “We as a rule gets everything but a square deal both in business and in law. . . . We are all through picking and ginning our cotton and the white people as a whole have it all in their hands and many have lived hard and will clear good money but the white people will wait until a few days to Christmas and then try to put the good and the bad in the same class and give them just what they want us to have and not mention justice to them.” James Willis related to an interviewer in 1939 how hard his parents worked on a sugar plantation in Iberville Parish and how little they received for their labor. He said, “Ma and pa couldn't figure, so they took whatever the man on the farm gave ’em. The folks said that pa worked himself a house. Yeah, in other words Pa made enough money to git him a house, but he never did git it. . . . And there is a lot of things I don't know about but I do know that pa was gipped.”13

Moving from plantation to plantation or from state to state was one of the few means available to agricultural workers to protest their working conditions. Though employers generally denied any connection between black migration and unfair labor practices, they sometimes admitted that it existed. Early in the twentieth century, newspapers in northern Louisiana reported that attempts by planters to “restore a form of forced labor” in the state had resulted in a mass exodus of African Americans to Arkansas, where they hoped to gain better treatment.14 In 1907 cotton planter Henry Stewart complained to a friend: “There is not enough labor here to go around and what is here is too unreliable and I think thoroughly organised. If one has labor one year it is a good sign that they will be short the next year, so in reality you make a little money one year and the next the place lies idle for the negro is punishing you for some small misdemenor which you have committed.”15

Black workers who stayed with their employers often took every opportunity they could to supplement their earnings. After inspecting his cousin Sarah's plantation in West Feliciana Parish in August 1910, Robert Stirling found one tenant “pasturing of horses” as well as making the expected crops, and told her, “He trades in horses at your expense.” Of another employee, Stirling advised his cousin not to charge any less than fifty dollars a month for rent because “Vattore is getting $50.00 per month from Ry Co. and yet he is trying to get house rent free from you[;] he and his boy also have quite a lot of cattle in your pasture.” Other planters in the parish found it necessary to post weekly notices in the local newspaper asking members of the public not to purchase wood, posts, livestock, or other farm products from tenants on their plantations without first gaining permission from the owners.16

For Louisiana planters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, theft was a serious problem. “The negroes around here have reduced cattle stealing to a fine art,” bemoaned Henry Stewart in 1906. “Some years ago we had 160 head and now I can count but 76 head of branded cattle and none sold in these years. I wonder if cows evaporate.” A year later, the owner of Hazelwood Plantation in West Feliciana Parish reported that several black tenant families had stolen cotton from the place, in spite of her manager's “seeming watchfulness.” Other items likely to disappear included harnesses, small pieces of machinery, hogs, corn, and seeds that workers either used themselves or sold to unscrupulous merchants in the dead of night.17

African American family moving, Opelousas, Louisiana, October 1938. For many plantation workers, abandoning their employers at the end of each crop year was one of the few means through which they could express their dissatisfaction with working conditions without risking eviction or physical violence. LCUSF33-011863-M3, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Black domestic workers as well as field hands commonly appropriated property from the homes of the white families they worked for. Taking away leftovers, or “pan toting,” was a widely accepted custom throughout the South. But as Jacqueline Jones has noted, “the service pan expanded in proportion to a black woman's needs and resourcefulness,” often without the knowledge or consent of employers. One white Louisianan who complained of being without domestic help in the 1940s stated that despite having to cook meals herself, “It is rather nice not to have a nigger eating up all your food and carrying off what they can't eat!” White people resented their servants’ tendency to take more than what was willingly given them, but domestic workers usually saw nothing wrong in these actions. One black cook chided an employer who initially refused to allow her to take home leftover food, saying, “The only thing we cullud people can do is get home and eat a little sumpin’ you white folks can't eat. Has that ever crossed yo’ mind, Missus Jakes? Is you humanity?” Smuggling food and other necessities out of the house to take home to their own families helped compensate for the low wages these women earned. Given the conditions of poverty that most were forced to endure, the justification was plain: white people had more than they could eat, and black people did not have enough, therefore they had a right to take what they needed. African Americans used theft to partially redress inequalities in the social order that white Americans had created.18 One white southerner observed that black people were “like the Isr[ae]lites when they left the land of Egypt, think they have a right to borrow and take all they could beat the Egyptians out off. The negro still think they have this right and exercise it when opportunity affords.”19

Though attempts by African Americans to improve their material status might be seen as simply matters of survival, they were more than that. As many black people realized, economic independence was a prerequisite to achieving real freedom and equality. They knew that during Reconstruction, their ancestors had voted and held political offices, and that those gains had been lost through violence, intimidation, and economic reprisals.20 As long as they too were forced to rely on white people for food, shelter, and other necessities, they could not hope to launch a powerful movement for change. In 1918 the president of a struggling NAACP branch in Shreveport suggested to the national office that the organization make some effort to provide “relief for the farmer that is swindled and cheated out of his money. . . . Loan these men and women (farmers) money assist them in securing credit and in a great many other ways help them.” Two decades later, another local leader noted the restraints that economic dependence placed on some African Americans’ ability to take part in organizing efforts, saying, “The man who has your job has you.”21

Activists Eual and Lorin Hall, who came from a family of black landowners in St. Helena Parish, remembered how this idea was passed down (and continues to be passed down) through the generations. “If you have no land, and no money, you're worthless,” Eual Hall stated. “There's nothing you can do, there's no fear you can put into nobody.” The Halls’ parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were “independent and free” and determined to keep themselves that way. Some were farmers, some were self-employed entrepreneurs, “and they were very, very strong in unity. . . . They believed in keeping things together . . . they would help one another maintain their property, whatever had to be done.” Older members of the Hall family still emphasized to younger people the importance of economic and political independence, both for themselves and for African Americans as a group. Identical values were impressed upon Willa Suddeth during her childhood. Raised on a farm near Shreveport, she recalled that her father told her repeatedly to “own your own,” and to strive for autonomy. “Grandfather and his brother went to great lengths to buy their own land,” she told an interviewer, “and it's still in the family.”22

Equally important to the freedom struggle was education. Since the passage of the first laws prohibiting enslaved people from learning to read and write, African Americans have recognized the empowering potential of literacy. In the twentieth-century South, the lessons were no less clear than they had been in the antebellum period. David Bibens, who grew up on a plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish, remembered that his grandfather's reading abilities and mathematical skills prevented the manager from cheating him at settlement time. After other sharecroppers began asking him to calculate their accounts as well, the manager arranged for some local thugs to administer a beating, causing him to stop this practice. Civil rights leader Robert Lewis of Concordia Parish recalled a similar incident that occurred on the plantation where he had lived as a boy. A sharecropper who had kept his own records confronted the landlord with his account book after being told that he had come out in debt, making the white man so angry that he refused to settle any more accounts that day. In the end the sharecropper received his money but was ordered to leave the plantation. Bibens, Lewis, and other rural African Americans were keenly aware of the value of education and the possibilities it offered for creating a better life for themselves and their children. Harrison Brown succinctly expressed the feelings of many black people when he stated, “Education—I ain't got it but I know the benefit of it.”23

Rural black people devised a variety of strategies to circumvent plantation owners’ efforts to deny them knowledge and power. By following their teachers as they moved from one regional classroom to the next, some students extended the length of time they attended school beyond the limits set by their parish school boards. Families living in communities that lacked high schools commonly sent older children to stay with friends or relatives in neighboring parishes to complete their secondary education. When state and local governments refused to build schools for black communities, African Americans constructed their own or held classes in churches and fraternal society halls. In a typical case, a study of schools in St. Helena Parish conducted in the 1940s found that the school board owned only two of the buildings used for educating African Americans. The remaining twenty-eight, attended by over 80 percent of the black children, were “housed in churches and in buildings erected mainly at the expense and efforts of the Negroes themselves.”24

Such feats were the result of a long history of school-building efforts by black communities dating back to Reconstruction. After conservatives ousted the Republicans from office in the 1870s, northern white philanthropists helped to fill the financial void left by state and local governments that refused to support black education. In the early twentieth century, donations from the Slater Fund, Anna T. Jeanes Fund, General Education Board, and Julius Rosenwald Fund supplemented the money raised by black communities to construct buildings, hire and train teachers, and buy equipment for classrooms. Small one- and two-teacher schools sprang up in parishes across the state, standing as tiny wooden monuments to African Americans’ commitment to education. After a decade of these efforts Leo Favrot reported to Julius Rosenwald, “No single effort in Negro education in Louisiana has created as much enthusiasm for better schools among these people as your benefaction. It will not be possible to supply the demand for new schoolhouses this year.” Between 1917 and 1932 the Rosenwald Fund helped to finance 435 school buildings that catered to more than 51,000 black students in Louisiana.25

Accepting help from white sympathizers was not without its problems. In return for their generous contributions, northern philanthropists expected teachers and administrators of the schools they funded to produce model black citizens who knew their “place.”26 Grambling College, the primary training ground of teachers for the rural schools, sought to make every graduate “an able teacher, a community leader, a farmer, a handyman, and an ambassador of good will between the races,” according to its president. The State Department of Education's Course of Study for Negro High Schools and Training Schools (1931) required teachers to “develop in the pupils an appreciation of the dignity and importance of manual labor,” and to impress upon students that “professional and ‘white collar’ jobs cannot absorb all.” Robert Lewis recalled that in the black schools of Concordia Parish, students never learned about African American rebels like Nat Turner or Harriet Tubman but were taught to admire “Booker Uncle Tom Washington” and other accommodationist leaders instead.27

Rosenwald school under construction, Millikens Bend, Louisiana, n.d. Efforts to ensure access to education for black children were among the most important elements of the long-term freedom struggle. L1167, Papers of Jackson Davis, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.

Yet a willingness to outwardly conform to social expectations often benefited black individuals and communities. Robert Lewis learned this when he watched an older man persuade white people to allow him to fish on their property by talking to them in a subservient manner. Martin Williams of Tallulah consciously “worked the system” using accommodationist tactics. “That was my strategy,” he said, and usually it was effective. In his home-town of Jackson, Alabama, Williams had a job driving a grocery delivery truck and became a favorite of several white families on his route by giving their children rides home from school whenever it rained. As a result, they always treated him well. Williams could not see any point in upsetting white people because, as he put it, “we ain't got no money.” Leaders like Williams reasoned that it was necessary to work through white people to get anything done because they were the ones who controlled the finances in Louisiana's rural communities. Willie Crain, a schoolteacher in Washington Parish, phrased it this way: “My race is alright, but they can't do anything for you.” Crain then related the story of how an extra room came to be added to the black schoolhouse. When the need for the addition first arose, some of the other teachers offered to donate money. But they were so poor that there was no way they could raise the necessary funds themselves. Crain said, “Then they had a meeting one Sunday afternoon, and I had Mr. Bateman [the superintendent] out to it, and he give us this extra room, just like that.” Both Williams and Crain were adept at persuading white people to provide needed resources for black communities. In their own way, these men and others like them were participants in the freedom struggle.28

Despite the assistance of white benefactors, most of the burden of improving educational conditions fell on African Americans. To construct a high school in the 1930s, residents of East Feliciana Parish had to first overcome the opposition of some white members of the community who argued that “the time is not ripe for one here because the colored children were needed on the farm or could work in the sawmill.” Next, they set about raising money and soliciting contributions. “We had to disrupt the school program and have teachers be responsible for a certain amount of money and the giving of entertainment made it impossible to conduct classes normally,” said the woman who spearheaded the effort. “But that was the only way we were able to get the training school.” In this and countless other cases, local black people initiated school-building programs, donated money and materials, and did most of the work themselves. As James Anderson has noted, African Americans incorporated financial aid from other sources into an existing tradition of self-help and fund-raising to provide for their own education.29

The struggle for education reflected and reinforced strong community ties that African Americans developed in their families, churches, benevolent societies, and fraternal orders. These institutions offered valuable support networks that black Louisianans relied on for survival. Sugar workers in Pointe Coupee Parish recalled that when people became ill and unable to work, friends and relatives “took up orders” for them at plantation stores, charging food and other necessities to their own accounts so that families who had fallen on difficult times did not starve.30 In a study of black workers on two plantations in West Baton Rouge and St. Mary Parishes, white investigator J. Bradford Laws noted derisively that his subjects had “an unfortunate notion of generosity, which enables the more worthless to borrow fuel, food, and what not on all hands from the more thrifty.” Laws and other white people criticized black people's failure to adopt entirely the individualistic, profit-seeking values of capitalist society, citing it as a major reason for their general poverty. But it was partly in response to poverty and insecurity that African Americans developed such mutualistic practices. The idea that no one should have to starve because of a bad crop, bad landlord, or bad luck held immense appeal to people who were acutely aware of their own vulnerability to economic disaster. Ruth Cherry explained the dominant philosophy among black people in her parish this way: “What you have, I have. What would hurt one, would hurt the other. Hospitality they call it, but it was the only way we made it through.” By emphasizing people's interdependence and their obligation to look after one another, black communities offered what James Scott calls “an alternative moral universe” in opposition to the dominant culture's self-centeredness and materialism.31

In addition to relatives and neighbors, African Americans could rely on their churches for spiritual, emotional, and material assistance. A study of twenty parishes conducted in the 1940s found that almost every black person belonged to a church and attended services and other meetings regularly. “To the church they contributed seemingly enormous amounts of money in proportion to their meager and inconceivably low incomes,” the researchers wrote. “Even those persons unemployed with no apparent source of income frequently stated that they made regular contributions to the support of the church. They have placed their utmost faith in this institution and willingly support it in all programs which it undertakes.” For many, the church was a haven, a place that offered some respite from work and suffering. One youth's account of a conversion experience reveals how religion brought joy to people whose lives offered few opportunities to savor such emotions: “Look like everything was new and I felt happy . . . and I told the Lord if He freed my soul, I'd serve Him all my days. . . . That was the happiest time my family had—when my brother and I got religion.”32

Some analysts have viewed the black church as a conservative force that deflected people's concerns away from the problems of this world and encouraged them to think only of what awaited them in the next. There is some truth in this assessment. In Louisiana, many African Americans belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, and their spiritual guides were usually white priests and nuns who had been assigned to, not chosen by, their communities. White religious leaders taught acceptance of white supremacy as a reflection of God's will and discouraged attempts by black people to rise above their prescribed station in life.33 In the black-controlled Protestant churches, limited training and a tendency to avoid challenging the social order made most rural preachers ineffective community leaders; even members of their own congregations sometimes viewed them with suspicion and scorn. Several Louisiana folk songs alluded to lazy, thieving, or philandering ministers, traits that seemed common among those who claimed that God had called them to preach. “I wouldn't trust a preacher out o’ my sight,” went one tune, “‘Cause dey believes in doin’ too many things far in de night.”34

Inside a plantation worker’s home, Melrose, Louisiana, June 1940. As the pictures decorating this bedroom suggest, religion was a central part of many black people's lives. LC-USF34-54651-D, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Despite these problems, black churches could and did act as agents of social change. Religion was an empowering force in many black people's lives, providing hope and a sense of being valued that counteracted messages of black inferiority and worthlessness projected by the white supremacist social system. Churches were places where African Americans met not only to pray, but also to socialize, disseminate information, make plans, and raise money to carry them out. In the early twentieth century religious institutions were central elements in school-building programs and other community projects. Moreover, they provided important social services such as health care, sickness and disability insurance, and assistance for those who were unemployed or too old to work.35

For a small fee, black Louisianans could join any number of other organizations that offered similar safeguards. In West Feliciana Parish, members of the Morning Star Society received medical and burial benefits for fifty cents per month. The Progressive Funeral Home owned by Dora B. Davis of Bunkie operated a hearse and ambulance service over a radius of two hundred miles, catering to over seven thousand people in six parishes. Black churches in Iberville, Pointe Coupee, East Feliciana, and West Feliciana Parishes contributed one dollar a month to the Home Mission Baptist Association in Baton Rouge in return for the care of elderly and infirm church members. The Knights and Ladies of Peter Claver, an organization of black Catholics founded in 1909, drew a large proportion of its membership from Louisiana. Aware that African Americans were “ruthlessly exploited economically” and that Catholics were persecuted in many parts of the United States, the order aimed to provide financial help, comfort for sick or disabled members, and opportunities for socializing.36

African Americans created a complex, overlapping system of benevolent societies, fraternal orders, insurance agencies, parent-teacher associations, and youth groups that reached into isolated rural areas as well as towns and cities in Louisiana. With the exception of a few exclusively male fraternal orders, membership and meetings were open to all. By enhancing economic security and assisting those in need, these organizations contributed greatly to the well-being of individuals and communities. In addition, they encouraged participation in efforts to improve conditions for black people. Activities sponsored by these institutions included attempts to increase employment opportunities for African Americans, alleviate racial tension, and improve health, sanitation, and educational facilities. According to one report, such concerns were less likely to be rejected by white people when they were raised by general community groups instead of more overtly political organizations like the NAACP. The author observed that although they seemed innocuous, many societies did “tend to show a civic interest that can only be made manifest through them yet they have no claim to the name of a so-called civic organization. These civic interests are accepted by many of the opposite race because their attitude towards the sponsoring group is not warped by preconceived ideas of their functions that may have been called out by a civic named club.”37

Black community institutions were subversive in other ways as well. Churches and society halls provided some of the few spaces where rural black people were relatively free from white supervision, and within their walls African Americans engaged in decision-making and other political processes that were denied them in the wider society. The St. Mary Parish Benevolent Society, for instance, established guidelines for acceptable behavior among its members and set fines for those who engaged in gambling or fighting. Many African Americans viewed these transgressions as harmful to their communities, but they were often ignored by local law enforcement officers as long as no white people were hurt. The society also provided short-term, interest-free loans, offering members an alternative to falling further into debt to white creditors in cases of emergency. At monthly meetings of the Bethel Baptist Church in Natchitoches Parish, representatives of the church's various districts followed standard parliamentary procedures as they discussed and voted on issues such as the disbursement of funds to needy members, censure and fining of those who were guilty of misbehavior, and long-term policies and programs.38

The social networks that rural black people established in their churches and societies went some way toward combating plantation owners’ efforts to keep them isolated and unaware of developments in the outside world. In 1928 one observer wrote: “Every negro mouth is a transmitter and ear a receiver. If anything of importance happens on a plantation to-night, every negro for forty miles around will know it by morning.”39 Throughout the twentieth century, this kind of “wireless telegraphy” was instrumental in enabling African Americans to seize opportunities to press their demands for equality when political or social developments encouraged them to do so. In 1934, for instance, black Louisianans who belonged to the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World managed to collect ten thousand signatures for a petition endorsing a federal antilynching bill then being considered by Congress. Black community institutions assisted in the organization of the LFU in the 1930s, and they were vital to the success of voter registration efforts and other forms of black protest after World War II.40

Despite the important sustaining roles they played and their potential political uses, churches and societies were not strong enough to overcome black Louisianans’ general poverty and powerlessness in the Jim Crow era. Disfranchisement and lack of access to the law forced black people to find other ways to fight injustice. Given white Louisianans’ frequent use of beatings, whippings, and lynchings, it should not be surprising that African Americans also sometimes resorted to aggressive tactics. In 1921 the NAACP's New York headquarters received the following report of an incident that occurred in Iberville Parish: “We heard a sugar cane farmer horsewhipped one of his Negro laborers—the Negro took the thrashing then shot the owner—four times. The white man went to his house for his gun—the Negro met him coming out of the door—and shot him again—this time in the mouth—then rear! . . . He was put in to jail and lynched that same night. The white man meanwhile lies in Baton Rouge hospital.”41

Individual reactions like these occurred with some frequency, with white antagonists often receiving more grievous wounds than those suffered by the Iberville Parish sugar planter. In 1926 black sharecropper Joe Hardy raised what he thought was a good crop on the plantation of John S. Glover in Caddo Parish. Expecting to clear several hundred dollars, he was surprised when Glover claimed that he owed sixty dollars instead. Hardy did not want to risk any trouble so he said nothing at the time. Later, he approached a neighboring planter who agreed to hire him for the next year and to pay his debt to Glover. When Hardy took his new employer's check to Glover, the planter attacked him and in the fight that followed, Hardy shot and killed his former landlord.42

A similar incident occurred near Franklinton, Washington Parish, a decade later. One morning in July 1934, white stock inspector Joe Magee stopped at the home of John Wilson, a prosperous black farmer, and became involved in an argument with Wilson's son Jerome about whether or not a mule he saw standing in the corral had been dipped. After the altercation Magee telephoned the sheriff, saying that he had been mobbed and threatened by the Wilson family. A short while later Magee returned to the Wilsons’ farm with Deputy Sheriff Delos C. Woods and two other white men. Jerome told them to take the mule for dipping if they wanted to. When Woods told him that they had come not just for the mule but for him also, Jerome asked to see an arrest warrant. Woods responded by grabbing Jerome, and when the black man resisted, the deputy shot and wounded both Jerome and one of his brothers. Jerome staggered into the house and returned with his gun. He fired one shot, the white men shot back, and either Jerome's or someone else's bullet killed Deputy Woods.43

Although African Americans generally tried to avoid dangerous situations, when they did encounter circumstances like those faced by Joe Hardy and Jerome Wilson it was not unusual for them to fight back.44 In the decades before national leaders and organizations began advocating nonviolent protest as a strategy to overcome racism, most rural black people placed more faith in their shotguns than in appeals to the consciences of white people when harm threatened. Johnnie Jones's father did not rely solely on his white friends to protect his son from violence after the car accident mentioned in Chapter 2. With the whole family expecting a mob to arrive at their house, Jones recalled, “My daddy didn't, didn't back up, he just loaded up his shot gun and loaded up his .44, that's the kind of pistol he had, and just waited for whatever would come, but nothing ever came.” Black lawyer Lolis Elie remembered being told about a similar incident when he was a young boy. In the 1930s Elie's mother was visiting her foster parents in Pointe Coupee Parish when the sheriff drove by and called out “Hey gal” as she walked along the road toward their house. She ignored him, and when he pulled the car over in front of her and asked why she had not answered him, she replied, “My name ain't ‘Hey gal,’ my daddy ain't no white man, and I don't have to answer you if I don't want to.” Her foster mother witnessed this exchange with horror. After Elie's mother entered the house, the older woman scolded her and locked all the doors and windows, expecting the sheriff and his deputies to come back and kill them. But when Elie's grandfather came home and heard what had happened, he told them to unlock everything and stationed himself outside with his shotgun. “They may come through that gate,” he said, “but ain't none of them gonna be alive to get to my porch.”45

African Americans who chose to defend themselves against harassment or violence took enormous risks, especially if a white person was killed or injured in the process. Jerome Wilson was eventually lynched for his role in the shooting of Delos Woods. Joe Hardy narrowly escaped this fate, but most were not so lucky. A black man in Tallulah and another from Caddo Parish both paid with their lives after shooting their white employers. In a tragic incident that occurred near Alexandria in 1928, an angry mob retaliated against William Blackman's entire family after he shot a deputy in self-defense and was shot and killed himself. The mob lynched Blackman's two brothers, burned seven homes, and drove all his remaining relatives out of the parish.46

“Homicide” was the reason given for nearly 2,000 recorded lynchings that occurred in the South between 1882 and 1946. “Felonious assault” accounted for another 202 of these murders, “robbery and theft” for 231, and “insult to white person” for 84.47 Perhaps nothing more effectively captures the ambiguous meaning of infrapolitical activity than these statistics. On one hand, they show that African Americans were far from acquiescent in the first half of the twentieth century. On the other, they reveal the limits of protest in a setting where white people's political, economic, and firepower always overwhelmed any resources that black people had access to.

The effect that individual, informal acts of resistance had on the southern social system is much more difficult to gauge than the achievements of organized political movements. But evidence suggests that they had at least some impact. Beneath the surface of newspaper articles proclaiming that harmonious “race relations” existed in the region, white Louisianans lived in a constant state of tension with their African American neighbors. In letters to his fiancée, Henry Stewart complained incessantly of problems with black workers on the two plantations he managed in West Feliciana Parish in the early 1900s. Their faults included taking unexpected holidays, disregarding his advice about when to pick their cotton, and leaving at the slightest provocation.48 In 1908, after the arrival of the destructive cotton boll weevil provided an incentive to cut back his cotton crop and rely less heavily on African American labor, Stewart wrote with some relief, “I would not return to the negro and cotton for anything.”49

Other planters had similar problems. In 1933 a social worker who visited a plantation owner and his wife in Tensas Parish noted that they were having trouble with one family of tenants, writing in her report: “They are very anxious to get rid of this family, for the reason that they keep the plantation in an uproar nearly all the time. This type of people nearly always instill an instin[c]t of fear into their employers, due to their treacherous and revengeful natures. They will not fight in the open, but will burn your house down when your back is turned.”50

The knowledge that black people were not completely docile had a more significant effect than keeping the white community perpetually on edge. One of the reasons why the Wilson family of Washington Parish had been so successful before the shootout in 1934 was that they knew both how to get along with white people and when to stand up for their rights. Jerome Wilson was the grandson of Isom Wilson, a former slave who achieved land ownership with the help of the family he had served before the Civil War. One day in the early 1900s Isom's daughter Ophelia was plowing a field near a road when a white man rode by and asked, “Say, gal, you want to do a little business?” Ophelia screamed, bringing Isom running across the field with his shotgun. The white man had to flee for his life. According to Horace Mann Bond, “News of that got around, too, and didn't anybody try to joree with any of Isom's girls after that.”51

As this story suggests, incidents of armed self-defense sometimes had a lasting impact on white behavior. After Jerome Wilson was killed in January 1935, African Americans in Washington Parish were afraid that there might be more lynchings and white people were just as afraid that the black community might retaliate. For several weeks, it seemed, white inhabitants were extremely careful not to offend anyone. “They ain't bother you,” a local black woman reported. “Mr. Barker says they can't be too nice in the stores. They jump around trying to wait on you.” In the early 1940s a school principal claimed that relationships between white and black people in Washington Parish were “very good.” He explained: “It seems that some shooting which occurred about five years ago made things better. We had a series of murders during that time, starting off with the shooting of a white sheriff by an unknown Negro. When a Negro was killed by a white man, then the Negroes would turn around and kill a white man. The white people developed the saying—‘You know, these niggers around here will kill you.’” The shootings prompted a group of prominent white residents to meet with black community leaders to discuss the situation, and after that the violence subsided.52

Although they courted disaster, the actions of people like Isom and Jerome Wilson drove home to white people the danger of pushing African Americans too far. Just as black people knew that retaliating against white violence risked death, white people were aware that instigating violence also invited death, even if to a much lesser extent. African Americans only had to shoot back occasionally to influence white people's actions. Sporadic use of armed self-defense meant that white supremacists never knew when they might exceed black people's limits of tolerance, with potentially lethal consequences for themselves. That African Americans’ behavior was not always predictable might have been why Johnnie Jones's father and Lolis Elie's grandfather did not have to use their guns in the incidents mentioned earlier, although they were fully prepared to do so.

Both national and local civil rights leaders in the first half of the twentieth century recognized the role that armed self-defense played in the freedom struggle and encouraged its use. Antilynching campaigner Ida B. Wells-Barnett noted in 1892 that of the many black people who had been the victims of mob violence during the year, the only ones who managed to escape death were those who had guns and used them to fend off their attackers. “The lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well,” Wells-Barnett wrote, “is that a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection that the law refuses to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs as great risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life.” In a 1916 issue of the NAACP's Crisis magazine, W. E. B. Du Bois strongly criticized the black people of Gainesville, Florida, for their inaction during a recent lynching. He argued, “The men and women who had nothing to do with the alleged crime should have fought in self-defense to the last ditch if they had killed every white man in the county and themselves been killed. . . . In the last analysis lynching of Negroes is going to stop in the South when the cowardly mob is faced by effective guns in the hands of people determined to sell their souls dearly.” Five years later, in the wake of a riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that followed the attempted lynching of a black youth charged with rape, the Baltimore Afro-American praised the courage of African Americans in the city who had shown that they would “rather die than submit to mob law.”53

Black newspapers in Louisiana also commented favorably when the victims of attack fought back. After a black man shot and killed a white student during a fight in New Orleans in 1930, the Louisiana Weekly editorialized, “We do not condone the killing of this white student, but we will state that every Negro will not pass lightly by the insults and vituperations heaped upon their heads by roving bands intent on having fun at the expense of their darker brothers.” They also observed that several riots had been averted in the city because African Americans showed their willingness to defend themselves.54 The following year the Weekly praised the actions of a black man who took his son back to a store where a white boy, encouraged by the clerks, had hit him. The man demanded that his son be allowed to fight the white boy on equal terms, and after the white men agreed, the black boy beat his opponent. The report urged African Americans not to accept abuse, saying, “This boy's courage will increase, and as he grows older he will develop the true spirit which our race is so badly in need of.55

Although the accuracy of the newspaper's prediction in this particular case cannot be ascertained, the lives of many people who became involved in the civil rights movement seem to support the general thesis. In her study of the young black people who formed CORE's New Orleans chapter in the 1960s, Kim Lacy Rogers found that they were often the children of militant parents who had encouraged them to engage in informal acts of resistance against white supremacy. Rudy Lombard, who later became the project director for CORE's voter registration efforts in rural Louisiana, once defied the state's segregation laws by throwing a ball into a white-only park and inviting his friends to join him in playing there. For this action, his father rewarded him with a case of root beer. Lolis Elie described his parents as people with little money or education who nonetheless had “a great deal of pride.” His father once stood up to a foreman who harassed him at work and “told the story over and over how he took that white man on.” Jerome Smith remembered watching his father remove segregation signs on streetcars and said that his mother always insisted that white merchants address her as “Mrs.” Asked when he first became active in the freedom movement, Smith found it difficult to answer, explaining, “When I entered the civil rights struggle in a formal sense I had been involved in things in a personal and private sense for so long.”56

Local activist Robert Lewis's experience also reflected the connection between infrapolitics and organized politics. Lewis frequently expressed his dissatisfaction with the social order in small ways before CORE arrived in Concordia Parish and provided a structure for more open protest. When the white high school in Ferriday invited children from the black school to watch their football team play, Lewis and his classmates arrived to find that they would not be allowed into the stadium. They were expected to go to one end of the field where there was a gap in the fence and peer through that. Lewis refused to be insulted in this way and left. Another time Lewis took revenge on a fast-food vendor who always made African Americans wait at a side window while he served white people at the front of his van. “I ordered about five hot dogs, chili dogs with the works, and five chocolate malts, and while he was fixing them, when he got on the last one I got on my bicycle and . . . left him there,” he said. “I learned how to protest, I guess, in my way.”57

Despite the enormous obstacles to black political activity in the first half of the twentieth century, African Americans in rural Louisiana were not apathetic or inactive during this period. By leaving plantations where they were mistreated, ensuring access to education for their children, creating strong social institutions, and fighting back against violence, black people showed that they did not accept their assigned place in the social order and laid the foundations for protest that organized movements built on. As the following chapters will demonstrate, when changes in the political and economic landscape of the region opened space for action, black activists were quick to take advantage of opportunities to openly demand their citizenship rights.