5 With the Aid of God and the F.S.A.:

The Louisiana Farmers’ Union and the Freedom Struggle in the New Deal Era

Beginning with a sharp drop in agricultural prices soon after the end of World War I, rural Americans were the first to experience the effects of the economic crisis that eventually afflicted the entire nation. Severe flooding in 1927 followed by the worst drought on record compounded the situation in Louisiana's plantation parishes. Landowners lost their farms, tenants’ debts increased, and competition for jobs drove down wages. National economic growth began to slow in 1929, and the financial panic of October that year precipitated a wave of bank failures, forced businesses into bankruptcy, and threw millions of people out of work. The effects of the Great Depression were particularly harsh for African Americans. Already among the poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population, black people's incomes now dropped even further below subsistence level. In the parish where Moses Williams grew up in the 1930s, farmers who could no longer afford to buy shells for their shotguns were reduced to chasing rabbits and other wildlife with sticks to obtain food for their families.1

Similar scenes of desperation were repeated all over the nation. The United States had experienced economic slumps before but never on such a wide scale. The extent and duration of the depression provided the rationale for a decade of experimentation by the federal government in an attempt to find solutions to social problems. Although President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal policies brought some benefits for African Americans, the limits of these reforms were soon exposed in the South, where local elites used their control over the administration of government programs to further enhance their power. Meanwhile, left-wing groups organized farmers and working-class people across the nation to push for more far-reaching changes.

Encouraged by the communist organizers of the SCU, poor white and black farmers in rural Louisiana formed the LFU to challenge federal agricultural policies that mostly benefited large, corporate landowners. African Americans provided the union's strongest leadership and support and used their locals to demand economic justice, better schools, political rights, and the safeguarding of their lives and property. Plantation owners responded with threats, evictions, violence, and attacks on government farm programs that assisted poor people. By the end of the decade the forces of reaction had succeeded in turning back reform efforts and minimizing threats to the social order. Nonetheless, the New Deal era brought important changes to the region and to the lives of African Americans, portending even greater transformations that encouraged more protest activity in later decades.

The small group of elite white people who monopolized power in Louisiana had not been without opposition in the early twentieth century. Poor white farmers and workers whose interests clashed with those of planters, merchants, and corporation owners nurtured deep resentment toward the state's conservative rulers, and middle-class progressives hated the rampant corruption that characterized electoral processes. Pressure from these groups resulted in some educational and political reforms during the governorships of Newton Blanchard (1904–8) and John Parker (1920–24), but real change came only with the election of Huey Long in 1928. A native of Winn Parish, an area that was mostly populated by white small farmers who had a long history of antiplanter sentiment, Long garnered mass support by pledging to pass legislation to curb the power of the wealthy minority and enhance the fortunes of people who were less well off. In a paradox that has invited both condemnation and praise from his biographers, Long combined corrupt and brutal political practices that placed Louisiana under a virtual dictatorship with measures designed to help the state's poor. During his term he abolished the poll tax, introduced a graduated income tax, regulated utility rates, and increased spending on public schools and transportation networks.2

Although Long was no less racist than the conservatives he replaced, for African Americans his governorship was an improvement over previous administrations. The Louisiana Weekly acknowledged that “Huey Long was for the common man, definitely throwing all his legislation in their favor, and as Negroes are certainly classed with the commoners, they benefited by Long's work.” Another source noted that despite Long's tendency to “mispronounce” the word “Negro,” African Americans shared in the better roads, free school textbooks, lower taxes, and reductions in phone, gas, and electricity rates that were among the achievements of Long's regime.3 An assassin killed Huey Long in 1935, but his legislative program for the most part remained intact even after his political opponents regained power. In addition, the growing economic crisis and demands for action from across the United States encouraged the federal government to implement similar social welfare measures on a national scale.

The 1930s were promising years for Americans who believed that some regulation of capitalism was necessary to alleviate the effects of economic insecurity inherent in the system. The depth of the depression exposed the inaccuracy of the belief that prosperity was guaranteed to anyone who worked hard and obeyed the law. Poverty or the fear of poverty affected people of all classes, making them more willing to accept change. Nowhere was this truer than in the South. Some of Roosevelt's strongest supporters were rural southerners whose livelihoods were endangered by falling crop prices and crippling debts. In the early part of the decade, even the region's conservative plantation owners joined in demanding government intervention to protect farmers from the ravages of the free-market economy.4

Roosevelt and a newly elected Democratic majority in Congress took power in 1933. Over the next decade the administration enacted a string of measures aimed at mitigating poverty and restoring economic stability. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and later the Works Progress Administration (WPA) allocated approximately $14 billion to the states to be used either as direct payments to unemployed people or wages for work on public projects. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) attempted to standardize business operations and improve workers’ lives by establishing industrywide codes for maximum hours and minimum wages. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided jobs and training for young Americans on reforestation, swamp drainage, and flood control schemes. To rescue the nation's farmers, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) paid subsidies to those who voluntarily reduced their crop acreages in an effort to eliminate overproduction, increase prices, and raise rural people's living standards. The Resettlement Administration and its successor agency, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), provided low-interest loans and other assistance to marginal farmers to help them achieve self-sufficiency.5

The New Deal raised black people's expectations, encouraging them to believe that they might finally be recognized as citizens. Federal policy stipulated that the newly established relief agencies must treat everyone equally, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt achieved notoriety among white southerners for speaking out against racism. Franklin Roosevelt's record in this respect was more ambiguous, but most black people nevertheless viewed his presidency as a positive development. In the 1930s those who were able to vote defected in large numbers from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party. For the first time since the Civil War and Reconstruction, African Americans believed that the government was on their side. A black sharecropper whose crops had been stolen by his landlord in Red River Parish expressed this new mood when he appealed to the Department of Justice for help. “I am told that President Roosevelt is a true friend to the negro people,” he wrote. “I want you and him to aid me, please.”6

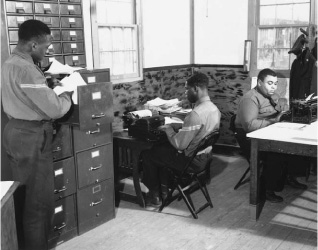

The New Deal did improve the lives of many African Americans. Between 1933 and 1939 approximately 8,600 young black people in Louisiana took part in the CCC program, with significant benefits for themselves and their families. Enrollees received thirty dollars per month and were required to send twenty-five dollars home to their parents or dependents. In addition, the training and opportunities offered enabled many of them to pursue careers other than unskilled farm labor. Madison Parish civil rights leader Martin Williams, who spent several years working at CCC camps near his hometown in Jackson, Alabama, remembered well the effect that the project had on participants. “We had some boys come there, had never seen a tractor or piece of heavy equipment,” he said. “Give them two weeks, they'd do anything you wanted done. They learned so quick—all they need is a chance.” As well as providing the basic education that many rural black people lacked, the CCC gave instruction in vocations such as carpentry, mechanics, landscaping, and clerical work. One project for African Americans in Pointe Coupee Parish offered a journalism course as well as classes in reading, writing, history, government, and debating. Such curricula were unlike anything most black people had been exposed to in the state's regular school system, and they were quick to recognize the value of these programs. Attendance at classes was voluntary but averaged around 90 percent. As one government study noted, African Americans used the camps “as a means of escaping the hardships of farm life and for [the] purpose of securing better pay and learning a trade.” This was exactly the path followed by Martin Williams, who came from a sharecropping family, trained as a drycleaner as part of the CCC program, and later established his own business in Tallulah.7

Civilian Conservation Corps camp, location unknown, n.d. Thousands of African Americans in Louisiana took part in the CCC program between 1933 and 1939. The camps provided education and training for jobs—such as clerical work—that most rural black people had not had access to before the 1930s. RG 35-G-41-2124, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Other relief programs offered similar chances to escape from plantation labor or brought improvements to rural communities that benefited both white and black inhabitants. Access to government aid made African Americans less dependent on white employers and more likely to assert themselves when they thought they were being mistreated. Unemployment benefits and wages earned on public works projects provided recipients with stable incomes and pumped money into local economies, helping communities to recover from the depression. Louisiana reported a 4.3 percent increase in industrial employment between July and October 1936, with some regions experiencing economic growth for the first time since 1929. In Tallulah, the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company added a power plant, veneer mill, and box factory to the sawmill it had built there in 1928, creating more than four hundred new jobs.8 Operating under the NRA codes after 1933, the company paid sawmill workers a minimum wage of twenty-four cents per hour for a forty-hour week, significantly more than most farmworkers could expect to earn at that time.9 Both Martin Williams and Harrison Brown moved to Tallulah in the 1930s to take advantage of the new opportunities, forming part of a migration that increased the town's black population by a little over two thousand.10

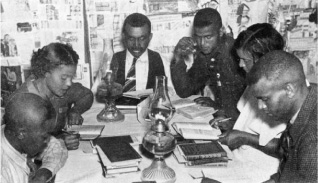

Another promising development for African Americans came in the area of education. Efforts to eliminate illiteracy in Louisiana initiated by state officials in the 1920s received added impetus when the federal government provided more funding for adult education programs. State WPA officials reported in 1937 that nearly ten thousand African Americans had enrolled in literacy classes and were learning “for the first time to read, write their names, figure the amount of their crops.” By 1939 more than twenty-five thousand black people were receiving instruction. Black people's dedicated participation in the program defied white stereotypes that had portrayed them as uninterested in education or incapable of learning. One account stated that students were “rearranging their entire lives in order to take advantage of the opportunity for knowledge,” noting that a group in De Soto Parish attended lessons during its noon break in the cotton fields each day. An issue of the Louisiana WPA's newsletter Work printed a photograph of some rural black people clustered around a table in a plantation schoolroom with the caption: “Both men and women have put in a hard day in the fields—but they never miss a class.”11

Having been deprived of education for so long, black students were not about to pass up the chance of achieving literacy when it presented itself. In a letter to President Roosevelt, J. H. Chapmon stated, “I truly do thank God for the blessing that he extended to the colored race here through you and those who took part in this great program. . . . I am thinking of when I was a school boy. They only let the colored people have four months in which to go to school. . . . Now you are helping me to get that that I was debarred of then.” Leola Dishman of Ferriday expressed similar sentiments. “We are trying and doing our best to learn the things heretofore we haven't had a chance to get,” she told the president. “We thank you for the privilege.” Annette Nelson from Ouachita Parish wrote to WPA administrator Harold Hopkins, “I am doing all in my power to grasp this wonderful opportunity. . . . Thanks for the opportunity.”12

Adult literacy class being held in a “plantation shack,” Louisiana, 1938. This photograph appeared in a publication of the Louisiana Works Progress Administration with the caption “Both men and women have put in a hard day in the fields—but they never miss a class,” indicating participants’ determination to take advantage of this educational opportunity. Work , April 1938, 4, Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

The WPA's efforts to reduce illiteracy among black Louisianans were among the most significant contributions of the New Deal. In many other areas, the effects of government programs were disappointing. One of the chief limitations of federal relief measures was that the amount of money allocated was inadequate to provide for all those who needed assistance. The federal government's rural rehabilitation programs, for instance, reached only a fraction of the nation's low-income farmers.13 Similarly, public works projects could not provide employment for every person seeking a job. As was the case throughout the nation, many more people applied for aid in Louisiana than officials were able to handle. In July 1936 the WPA posted notices in local newspapers asking residents not to attempt to enroll in the program, since the relief quota for the state had been filled and no more applicants could be accepted.14

Governor Richard Leche received hundreds of letters from impoverished Louisianans who had been rejected at their local welfare offices and did not know where else to turn. Charlie Young, a seventy-one-year-old black man from St. Mary Parish who was half blind and unable to work, was refused assistance because he had three children who supposedly were able to support him. He told Leche, “They Said for my children to help me But my children aint got nothing Them self.” Lillie Pearl Jackson begged the governor to help her find employment. She wrote, “I am hungry my two children are hungry we are without clothes, and shoes my husband needs medicine will you please help me? I do not mind working but I cannot get a job. . . . Please, please, please help me if you please or I will starve.” In 1938 twenty-four unemployed residents of Concordia Parish sent a petition to Leche demanding that he do something about their plight. “We have exhausted every known means at our disposal without avail in an effort to obtain work—or even information about work,” they stated. “Our credit has been exhausted through inability to pay; our rent is long overdue because of lack of funds. We are without food! We are hungry! We are desperate! . . . We look to yourOFFICE as a last desperate appeal!”15

The inadequacy of relief affected both white and black Louisianans. African Americans faced the added problem of racism. Establishing a general commitment to equality at the national level was easier than ensuring the impartial administration of programs at the local level, particularly in the South. In 1933 the higher wages and shorter hours demanded by NRA codes resulted in mass layoffs of black workers, whose jobs were given to white people. The Louisiana Weekly reported that although the official policy of the government was to “thunder against discrimination,” employers were “disregarding it right and left, where Negro labor is concerned.” Louis Israel informed black lawyer A. P. Tureaud that African Americans in Iberville Parish received lower wages than the white laborers employed on public works and were being treated unfairly in other relief programs. In 1935 federal WPA director Aubrey Williams told a congressional committee that racism was a serious problem in New Deal agencies, attributing it to “‘local traditions’ invoked in many sections of the country.”16

Rather than discouraging or undermining the South's “local traditions,” in many respects the New Deal reinforced existing power relationships. Throughout the region, administrators were selected by the same planters and business owners who dominated everything else. In West Feliciana Parish, some of the men appointed to oversee federal programs included merchant, farmer, and sheriff T. H. Martin, plantation owner Howard Spillman, and storekeeper Thomas Woods. Wealthy landowners like Dr. J. H. Hobgood served on the parish board of public welfare in Pointe Coupee Parish. A survey of the landholdings of AAA committee members in the Louisiana sugar belt found that the majority were large growers and corporation owners unsympathetic to the problems of small farmers, tenants, and sharecroppers. Control over crop acreage allotments enabled planters to ensure that they received the biggest share, while the amount of land other farmers could cultivate was drastically reduced. As had always been the case, the authority to decide who would or would not receive aid lay with the most powerful people in towns and parishes. Access to federal dollars in addition to their own wealth only increased their influence.17

The policy of placing New Deal programs in the hands of local elites proved disastrous for black people. One man who informed the WPA's national office about the terrible working conditions and low wage rates African Americans endured on a project in Louisiana stated, “We are now worser off on the WPA . . . than our foreparents was in slavery. If we open our mouths to say anything we loses our job, which the Federal government have provided for us.” In 1936 C. L. Kennon of Webster Parish complained, “just because I would not leave my home and go work on half [as a sharecropper] for another man they cut me of[f] the relief—and won't let me back on. I have ben begin this relief office hear for 6 month to put me to work so I can buy my little children some clothe and shoes to send them to school.” In Iberville Parish, merchants subverted relief programs by having food and other supplies intended for needy people sent to their stores, where they sold the goods instead of distributing them to the poor.18

White employers believed that government handouts made black people “lazy” and discouraged them from accepting work when jobs were available. Welfare payments and the wages paid by the WPA were meager, but they were still more than African Americans could earn as agricultural laborers and domestics. Many people showed an understandable preference for government over private employment. According to one official, a household workers’ training project that operated in Louisiana for about a year “spoiled Negro women” by offering wages of up to seven dollars a week compared to the three or four dollars a week most had previously been paid. Now, he said, they thought they were “superior maids who could command big wages.” Some of them refused to do any domestic work at all, preferring “sewing or some other WPA project.” The white extension agent in West Feliciana Parish reported that “farm laborers and tenants have received so much assistance from relief agencies . . . that a great many of them have concluded that the Government will take care of them whether they work or not, and, therefore, they take things easy and get by with [as] little work as possible.” In a similar vein, Guy Campbell of Monroe complained to Senator Allen Ellender that New Deal programs were having the “worst possible evil effect” on African Americans in the region. He claimed that black laborers who drew ten dollars a week on relief refused to go to work picking cotton despite plantation owners’ desperate need for their services.19

Faced with such threats to the social order, white community leaders sought to prevent black people from taking advantage of the alternatives to plantation labor offered by federal agencies. Public works projects could be established only in response to requests by local officials, and police juries seemed reluctant to take the initiative. A WPA administrator who had been trying to encourage statewide plans for building farm-to-market roads reported, “many of the parishes are unable to pay engineering costs and in other cases, the Police Jurors who are the governing bodies of the parish, have been very slow in getting up data for projects. I am inclined to believe that they have been told to do nothing and not to cooperate with us.” Similarly, district supervisor Mildred Taylor found that a black women's sewing unit in Concordia Parish was poorly operated, observing, “The Sponsors have contributed nothing and apparently have showed very little interest.” Complaints that African Americans made too much money on WPA projects resulted in new regulations that cut the amount of time they were allowed to work in half, so that black people could earn only $19.25 for two weeks of labor a month instead of $38.50 for the full thirty days.20

As in the past, some white people used violence to try to force African Americans back into their traditional roles. In 1933 and 1934 a number of beatings and murders occurred in Union Parish to discourage black men from signing up for relief. A letter reporting the incidents to the Department of Justice listed two men who had been killed and four others who had been whipped (along with the names of twenty-one white men who were responsible for the terror) and added, “9 men run away from home all had to leave their homes wives and children to keep white people from killing them.” Two near-riots occurred in St. Landry Parish when a black CCC camp was established there in June 1933. An investigator attributed the trouble to “intense racial feeling” in the community. A more specific motive was implied in a similar case reported to the U.S. attorney general by the secretary of the National Negro Congress in 1940. The Ku Klux Klan harassed and intimidated residents of a job-training camp for African Americans, posting signs that read, “Niggers your place is in the cotton patch.”21

Plantation owners complained incessantly that federal programs encouraged black people to refuse to work and created intolerable labor shortages in rural areas. N. Watts Maddux of St. Bernard Parish claimed that he knew of hundreds of former farmworkers whose talents were being wasted on useless WPA projects that seemed “purposely long-drawn-out and needlessly so.” In October 1942 a sugar grower in Avoyelles Parish who was unable to match the wages paid by relief agencies politely requested the closing of WPA camps in the region until the cane-cutting season was over. The same year, the Caddo Parish police jury passed a resolution calling for the suspension of welfare programs, stating that an “extreme shortage of labor” had been caused by “giving public funds to undeserving persons, who wish to be supported by the government in idleness.”22

Most complaints about labor shortages were exaggerated if not completely fabricated. In one case, an investigator found that employers were able to provide the names of only two workers believed to be on WPA projects instead of laboring in the fields. His report concluded that “complaints made about pickers not being available were generally made without facts to substantiate the claims and were of such a general nature that they were of no help to the W.P.A. in relieving the situation; that W.P.A. did release all workers with the proper background and that the needs of the growers were satisfied.”23 Referring to the Caddo Parish resolution, a state department of labor official informed Governor Sam Jones that “it was not a question of lack of labor but the low wage scale which controlled that situation.” Plantation owners in the region had offered workers only $1.25 per hundred pounds of cotton picked when their competitors on the state's eastern borders were paying from $1.50 to $2.00. As the harvest season progressed and more labor became available, the Caddo Parish planters reduced their rates to $1.00, indicating that no real crisis existed.24

In fact, as these investigators’ comments suggest, administrators worked hard to ensure that New Deal programs did not interfere with rural labor markets. State WPA director J. H. Crutcher warned his staff in 1936 that the agency would “under no circumstances be a party to creating a labor shortage, and District Directors will be held personally responsible for seeing that no such condition exists in localities where persons are employed on W.P.A. projects and undertakings.” He told them not to wait for private employers to complain, but to ensure that labor was available by releasing workers from projects whenever necessary. The WPA's newsletters and public announcements stated repeatedly that its aim was to provide employment for farmworkers only during the off-season. Relief programs were routinely shut down during agricultural harvest times so that welfare recipients could work in the fields, thus protecting the interests of employers who were unwilling to compete with the wage scales offered by public works projects.25

At the same time that they demanded a ready supply of cheap labor at certain times of the year, plantation owners were becoming less willing to support surplus workers when they were no longer needed. One of the most significant consequences of the New Deal for rural black people was the displacement of thousands of sharecroppers and tenants as a result of the federal government's farm policies. With the reduction in crop acreages brought about by the AAA, plantation owners’ need for labor decreased. In addition, many growers invested their subsidy payments in machinery that further reduced their need for workers. Farm implement companies had been experimenting with labor-saving agricultural technologies since the nineteenth century, and by the late 1920s mass-produced all-purpose tractors like International Harvester's McCormick-Deering Farmall were widely available. Tractors could be used instead of mules for plowing and planting cotton, and with special attachments they could also perform a range of functions in sugar cultivation. Large landowners in the Mississippi River delta regions were the first to begin using the new machines in the South, and sales to southern planters increased rapidly after 1935. Between 1930 and 1940 the number of tractors in Louisiana almost doubled, increasing from 5,016 to 9,476. The state's plantation parishes showed the highest increase (386 percent) in the number of tractors per thousand acres of crops harvested of any southern region in the same period.26

With fewer acres in cultivation and the use of tractors spreading, the number of black tenant families in Louisiana dropped by nearly fifteen thousand in the 1930s. The Department of Agriculture attempted to ensure that employers retained tenants on their plantations and shared AAA payments with them, but loopholes in the agency's regulations allowed unscrupulous planters to avoid these obligations. Welfare officials in Louisiana noticed the prevalence of “old plantation negroes who are no longer able to work for a living” on their rolls and concluded that many landlords were taking advantage of the New Deal to rid themselves of unproductive laborers.27

Workers who remained on the plantations were easily cheated out of their AAA payments. Government officials decided that federal policy should not interfere with traditional labor contract arrangements in the South, allowing planters to continue manipulating accounts and limiting their employees’ incomes. In its first two years of operation, the AAA distributed subsidy checks to landlords and entrusted them with the task of disbursing the appropriate portions of these funds to sharecroppers and tenants. Many agricultural workers failed to receive their share, so in 1936 the administration began mailing plantation owners multiple checks made out in the names of individual employees. It remained an easy matter for landlords to coerce workers into signing the checks over to themselves. Illiterate sharecroppers were forced to mark these mysterious slips of paper with an X without fully understanding what that meant. Another ploy was to make sure that the money could only be spent at plantation stores. Harrison Brown remembered “when the government had ordered you'd get a check or something after you settled . . . they took that check. . . . And the way they took it you couldn't cash it in town nowhere, you had to go by your merchant and let him sign it to cash it in—that was so he could get his hands on it, but you'd have to go by them.”28

Planter abuses of New Deal programs did not go unchallenged. The massive social upheaval caused by the depression gave rise to radical workers’ and farmers’ movements that struggled to influence national policy and enhance equality, opportunity, and security for all Americans. In 1931 members of the Communist Party began working among rural black people in Alabama, encouraging them to form the SCU in an effort to increase the bargaining power of agricultural workers and help them gain fair treatment from landlords. Socialists in Arkansas organized the interracial STFU in 1934 to fight the mass eviction of tenant families caused by the AAA. The STFU spread into Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and parts of Mississippi, attracting thousands of members. At the same time, liberals in the Farmers’ Educational and Cooperative Union of America (more commonly called the National Farmers’ Union or NFU) began to increase their influence over that union's leadership, advocating federal legislation that was more responsive to the needs of small farmers. The activities of these rural unions and the publicity generated by plantation owners’ violent opposition were instrumental in drawing nationwide attention to the plight of southern tenants and sharecroppers. The modification of some AAA policies in the later half of the 1930s and the expansion of programs to help displaced and low-income farmers buy land of their own resulted in part from union pressure.29

The LFU was formed in the mid-1930s, originating as an offshoot of the SCU. In Alabama, lynchings, beatings, and evictions had driven the SCU underground, forcing its members to meet secretly and limiting its effectiveness. After a strike by cotton pickers in Lowndes County was violently crushed in 1935, union leaders began searching for ways to strengthen the organization. Strong interest shown by black farmers in Louisiana encouraged the SCU to focus some of its attention on that state, and initially it seemed that the union would meet less resistance there than in Alabama. In January 1936 SCU secretary Clyde Johnson reported from Louisiana, “We have locals of 20 to 175 members that meet in churches and school houses and when some little terror did start against one member one of our leaders went to see the Sheriff in the name of the Union and the Sheriff didn't say a word about him being a Union member.” Communist organizers worked with local people to make contact with black farmers and encourage them to attend meetings to discuss the union. Those who were interested in forming a local then elected officers and recruited more members by approaching family, friends, and neighbors. The social networks that existed within churches and other community institutions provided useful structures for disseminating information about the union. By May 1936 the SCU had approximately one thousand members in Louisiana, and the union had moved its headquarters to New Orleans.30

The SCU's New Orleans office was staffed by a small group of activists that included (at various times) Clyde Johnson, Gordon McIntire, Clinton Clark, Peggy Dallet, and Reuben Cole. Most were white southerners in their early twenties who shared a commitment to progressive causes and viewed their work as part of the fight for social justice. Clyde Johnson was the only northerner in the group and Clinton Clark the only African American. Originally from Minnesota, Johnson had attended City College in New York and worked as an organizer for the National Student League before joining the Communist Party and being assigned to Alabama in 1934. Though he eventually left the party, he remained committed to workers’ struggles throughout his life.31 Texan Gordon McIntire had attended Commonwealth College in Arkansas (a school that was closed down by the state in 1941 for “teaching anarchy”) before arriving in Alabama to work with Johnson and the SCU in 1935. Clinton Clark was a native of Louisiana who helped establish union locals in St. Landry, Avoyelles, and Pointe Coupee Parishes in 1936. Peggy Dallet had been involved in organizing local chapters of various left-wing organizations in New Orleans, including the American League for Peace and Democracy, the League for Young Southerners, and the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. She became the union's office secretary in 1937 and later married Gordon McIntire. Reuben Cole came from a sharecropping family in Georgia. Like McIntire, he had attended Commonwealth College and joined the other activists in Louisiana in May 1937.32

Members of the New Orleans staff acted as effective grassroots organizers, offering advice and aid to union members but encouraging local people to make key decisions about issues affecting them. The first issue of the union newspaper, the Southern Farm Leader, invited members to send in letters expressing their concerns and ideas for action, describing conditions in their communities, and reporting on the activities of their locals. Clyde Johnson recalled that whenever a new policy or position needed to be formulated, “everyone available met to talk it over. If it involved a basic union position we discussed it all over the union and tried to have a state meeting approve a position. . . . We believed the members had to understand and approve an action to have it be successful. Rubber stamps can't cooperate.”33

Relationships between organizers and local activists were characterized by mutual respect. At their first convention in 1936, union members passed a resolution thanking Clyde Johnson for his efforts on their behalf, calling him “one of the outstanding champions of the Southern day laborers, sharecroppers, tenants and small farmers.” Three years later Gordon McIntire noted the rapid growth of the union in Louisiana, saying, “Much of the credit must go to the Local leaders of the Union, whose courageous desire to improve the economic conditions and protect the democratic rights of brother farmers throughout the agricultural fields has been repaid by the success of the Union.”34

After establishing itself in Louisiana, the SCU attempted to further strengthen its position by joining forces with other farmers’ and laborers’ unions. In May 1936 Johnson wrote an editorial in the Southern Farm Leader suggesting that all of the 60,000 southern sharecroppers, tenants, and small farm owners who currently belonged to the SCU, the STFU, or the NFU unite in the largest of the three organizations, the NFU. Johnson had maintained friendly relations with STFU leader H. L. Mitchell since 1934, and the two unions sometimes cooperated on issues affecting them both. However, Mitchell and others in the STFU were wary of the SCU's communist affiliations, and they rejected the idea of a merger.35 The SCU's overtures toward the NFU were more successful. Hard-pressed small farmers and tenants among the NFU's all-white membership were beginning to see the value of uniting with black farmers to fight government agricultural policies that mostly benefited large growers. The union's more progressive elements saw an opportunity to strengthen their position by encouraging the transfer of SCU members to their organization.36 In return, NFU charters offered the former SCU locals the protection they so badly needed.37 Clyde Johnson hoped that the charters would enable union members to “meet openly without interference,” and that uniting with an established organization that had more than 100,000 members in thirty-eight states would “give the Black Belt farmers a much greater backing” in their struggles against plantation owners.38

In 1937 the SCU's locals in Alabama and Louisiana began transferring into the NFU, and the LFU was chartered as a state division of the national union.39 At the annual convention of the NFU in November, delegates from the southern states played an important part in electing new executive officers and replacing the union's traditional emphasis on banking and money reform with a program more in line with the needs of poor farmers. Resolutions called for legislation to help tenants achieve farm ownership, mortgage relief, crop loans, and price control, as well as cooperation between farmers’ organizations and industrial workers’ unions.40

Since the problems confronting agricultural day laborers were different from those of farm operators, SCU leaders urged that they be organized into a separate union affiliated with the AFL.41 In 1937 farm wageworkers in Alabama gained an AFL charter to form a union, but shortly afterward they joined the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), a new organization of farm and food processing workers sponsored by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Clyde Johnson then left the South to work with UCAPAWA lobbyists in Washington, leaving Gordon McIntire to head organizing efforts in Louisiana. McIntire encouraged wage laborers to join UCAPAWA and small farmers, tenants, and sharecroppers to join the LFU. The LFU maintained a stronger presence in the state than the CIO union, however, especially when financial difficulties forced UCAPAWA to abandon most of its rural labor organizing activities after 1938.42 To complicate matters, many LFU members worked as seasonal wage laborers at sugarcane-cutting time in addition to raising cotton or other crops during the year. For these reasons the LFU did not limit its activities to issues affecting tenants and sharecroppers, and its locals consisted of all types of agricultural workers.43

The union's “family membership” structure mirrored the tradition of earlier black community institutions in encouraging participation by women and young people as well as men. Dues were $1.50 per year for adult males; women and young men between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one could join for free. Non-dues-paying members were called honorary members but they had the same rights and privileges in local, county, and state unions as dues-paying members. Women took an active part in the union at both the local and state levels. Often more literate than men, they performed valuable services like writing letters, passing on information from printed sources, keeping records, and teaching other members how to read and write.44 Women delegates at the union's 1936 convention confidently expressed their opinions and ideas for action. Among the resolutions passed were several calls for measures to improve conditions for farm women, including equal pay for equal work, higher wages for domestic workers, free medical attention for pregnant women, and a maternity insurance system.45

The LFU welcomed white as well as black people, and strong local leadership was provided by members of both groups. As with all interracial unions in the South, the LFU's mixed membership presented problems.46 In keeping with the Communist Party's antiracism, organizers at first did not allow segregated locals, though they avoided challenging southern racial practices too openly. According to Johnson, “To be for equal rights, for freedom and for self-defense was enough. It covered all our problems. We never advocated ‘social equality’ in those words because in the white mind it was synonymous with demanding that a black marry his daughter. The racist propaganda hung so heavy on this that it was futile to argue.”47 In later years the policy on interracialism was not rigidly enforced, especially after opponents charged that the LFU was a “nigger union” in an attempt to discourage white people from joining. Gordon McIntire refuted the claim in the December 1936 issue of the Southern Farm Leader, explaining that the perception arose after a mass meeting in Opelousas where the black farmers appeared to overwhelm the white members in attendance. “They later realized that their enthusiasm had worked against them,” he wrote. “Both white and colored generally prefer to have their own locals and meet separately.”48

No precise statistics showing the ratio of white to black members are available, but the majority of LFU locals seem to have consisted of African Americans. The union did make some headway among poor white people in rural Louisiana. White farmer John Moore of Simmesport, for example, led efforts to organize a local in Avoyelles Parish before being attacked and driven from his home by a mob in July 1936. Most of the other local leaders were black, including John B. Richard (who served as vice-president of the state union), Abraham Phillips, and Willie and Irene Scott. The black men and women who joined the union were cotton farmers and sugar workers who welcomed the legal assistance, skills, and resources that organizers brought to the freedom struggle. The grievances that LFU members expressed in letters to the union newspaper and in convention resolutions reflected many long-standing concerns of rural black people, such as unfair crop settlements, inadequate schools, exclusion from decision-making on government policies that affected them, and lack of protection from violence. Joining the LFU signaled their intention to intensify the fight against inequality and injustice.49

The LFU's first real battle occurred in St. Landry Parish in 1936. For several months the union had been involved in a range of activities there, including forming a farmer-labor cooperative with maritime workers in New Orleans and pressuring state and federal authorities to provide relief to farmers after the region was struck by drought.50 In November, plantation owners in the parish made their first attempt to destroy the union, precipitating a fight that set LFU members against planters and their associates in local office. With the help of federal officials, the LFU gained a partial victory, but the incident showed that the union was far from welcome in Louisiana and that some white people were determined to do everything in their power to prevent it from interfering with the plantation system.

The struggle began when twenty families on St. Landry Farm learned that they were to be evicted because the bankers who owned the land wanted to sell it to the Resettlement Administration. Local administrators responsible for choosing farmers to participate in the planned resettlement project decided that LFU members would be excluded. Most of those who were told that they would have to leave were African American sharecroppers and belonged to the union. According to former manager Albert de Jean, all of them were good farmers. The families were served eviction notices in late November and ordered to move off the plantation by the end of the next month. As a statement prepared by the LFU pointed out, most rural workers made employment arrangements for the following crop season in July and August. The only landowners likely to have farms available this late in the year were “‘ornery’ landlords” who abused their workers. The St. Landry Farm families did not want to move.51

Eight union locals joined together to protest the action, demanding that the sharecroppers either be allowed to stay and participate in the resettlement program or be placed on good farms elsewhere with loans to buy their own equipment and supplies. Planters and parish officials responded by intimidating organizers and members. A group of white men that included Sheriff D. J. Doucet harassed Gordon McIntire when he went to collect affidavits from plantation residents in December. At a meeting held in Opelousas, vigilantes threatened McIntire and other union leaders while local resettlement supervisor Louis Fontenot “stood among the hoodlums grinning.” Toward the end of December, the Resettlement Administration sent Mercer G. Evans to investigate the LFU's charges of discrimination. After speaking to local officials, Evans said that he found no evidence of policy violations but suggested that the displaced sharecroppers might receive loans if they found new farms and applied for aid. Under continued pressure from the union, federal administrators finally agreed to loan the evicted families between four and five hundred dollars each to help them establish farms of their own.52

The LFU achieved similar success in a confrontation with landlords in Pointe Coupee Parish in 1939. Plantation owners had responded to stricter regulations forcing them to share AAA checks with workers by evicting sharecroppers and altering tenancy agreements so that they could keep a bigger proportion of the government subsidies for themselves. Tenant families were told that they must accept the new arrangements or leave. Union officials advised the farmers to stand firm while they lobbied the federal government to intervene. According to local leader Abraham Phillips, “One bad week followed another, for we never knew when the boss would stop bluffing and really put us out in the cold. But we kept building our membership during those anxious days, we appealed to the federal government, and finally won the support of the Farm Security Administration, so that we got better rent contracts for 1939 than we'd ever had before.” The FSA agreed to lease the plantations from the owners and arranged for tenants to pay cash rents of six dollars an acre. The settlement allowed the families to receive their full AAA payments, sell their own cotton, and follow a live-at-home program, offering them a chance to save some money and get out of debt that most had not previously had.53

The LFU also became involved in efforts to improve conditions for sugar workers. Under the Sugar Act of 1937, growers who wished to take advantage of the AAA subsidy program had to adhere to certain regulations, including the payment of “fair and reasonable” wages. These were to be determined each year by the Department of Agriculture after hearings were held to give planters, processors, and laborers the opportunity to present testimony to government officials.54 In October 1937 hearings to set wages for the coming harvest season were held at Louisiana State University, a segregated venue that prevented African Americans (who made up the majority of sugar workers) from attending. The morning session was taken up with growers who spoke of the poor prices they received for their product, implying that they could not afford to pay cane cutters any more than the current rates (on average, $1.10 per day or 65¢ per ton).55 In the afternoon, Gordon McIntire spoke on behalf of approximately one thousand LFU members whose complaints included inadequate wages, inaccurate weighing of cane, payment in scrip, excessively high prices charged at company stores, and inability to grow their own food. Some of the planters responded by praising the “beautiful paternalism of the old plantation system,” arguing that because workers received free housing, medical care, and other benefits, they did not need higher wages. Others claimed that black people were lazy and wasted all their money on gambling, so it was pointless to pay them more. However, since wage increases seemed inevitable, the growers indicated that they might accept rates of $1.25 per day or 75¢ per ton. After the hearings the LFU urged members to write to Joshua Bernhardt, chief of the AAA's Sugar Section, telling him why they needed higher wages.56 The final wage determination set minimum rates at $1.20 per day for women and $1.50 per day for men, or 75¢ per ton. The regulations prohibited growers from reducing wages “through any subterfuge or device whatsoever” and stated, “the producer shall provide laborers, free of charge, with the perquisites customarily furnished by him, e.g., a habitable house, a suitable garden plot with facilities for its cultivation, pasture for livestock, medical attention, and similar incidentals.”57

The Department of Agriculture held additional hearings in February 1938 to establish wages and working conditions for the planting and cultivation seasons. Peggy Dallet presented a statement by the LFU describing the miserable poverty that year-round employees on the sugar plantations suffered and calling for minimum wages of $1.20 per day for women workers and $1.50 for men. She refuted planters’ contentions that the provision of free housing and medical care compensated for low pay, saying that in most cases accommodations were not fit for human habitation and sick people paid their own doctors’ bills. Dallet requested that all payments be in cash and that workers be allowed to grow gardens and raise livestock for food. In July the AAA announced its regulations for the coming season, requiring growers to pay women at least $1.00 and men $1.20 per day and to provide the customary perquisites free of charge. Though the new wage determination was not as high as the LFU had hoped, it still represented a 20 percent increase over previous rates.58

These wage rates held steady for the next four years.59 Once the rules were established, workers fought to ensure that planters abided by them. The LFU taught its members how to keep records of what they were owed for the labor they performed each day and encouraged them to file complaints against employers who violated the law. Louisiana sugar workers submitted nearly four hundred wage claims to local and federal authorities in August and September 1939. At the request of the LFU, the Department of Agriculture withheld AAA subsidies from plantation owners until the claims were settled, and government agents investigated reports that employers in several parishes had threatened and intimidated their workers. The same year, union members in Pointe Coupee Parish refused to accept wages of one dollar per day from a planter who had evicted some families the previous year for filing complaints. As a result, they reported, he was “forced to live up to the law.”60

Support for the LFU grew steadily in the late 1930s. Between 1936 and 1938 the number of dues-paying members more than doubled, increasing from 400 to 891. Although this represented only a tiny fraction of the LFU's potential constituency, it was an encouraging start.61 Organizers found the response from African Americans especially gratifying. In November 1939 more than three hundred delegates from locals in twenty-five parishes attended the third annual convention of black members held in Baton Rouge, where they presented reports of their activities and listened to guest speakers from the AAA and FSA informing them of their rights under the federal government's agricultural programs. Gordon McIntire declared that it was “probably the largest meeting of sharecroppers and tenants ever held, but if not I will guarantee that it was the most unified meeting, and surely accomplished more than any that I have ever attended.” The delegates voted to work toward establishing parishwide organizations to coordinate the efforts of their union locals. Moreover, to make it easier for cash-deprived tenant farmers to join the union, they agreed to allow the collection of dues for 1940 after the current year's harvest.62

Some white observers in Louisiana ridiculed black people's participation in the LFU, arguing that the communists wanted only to manipulate the state's poor, ignorant sharecroppers for their own purposes. One report on the union stated that it was “a trouble making organization in that it puts ideas in the minds of the negro tenant farmers in Louisiana which could not possibly have originated there.” But African Americans were not as easily misled as these analysts believed. Black members saw the union as a powerful ally in their fight against exploitation and discrimination. They did not need to read Karl Marx or be “duped” by communist propaganda to sense the logic in the LFU's initiatives. Union organizers could not have been so successful if their analysis had not accurately described many aspects of rural black people's lives. As the Urban League's monthly newspaper Opportunity pointed out, black tenant farmers in Alabama and Louisiana knew nothing about theories of economic determinism or Marxist philosophy, “But these things they do know. They know of grinding toil at miserably inadequate wages. They know of endless years of debt. They know of two and three months school. They know of forced labor and peonage.”63

African Americans in rural Louisiana had been battling these evils in their own way before the arrival of union organizers. Membership in the LFU offered the chance to fight their oppressors on more even terms. Writing to the Southern Farm Leader “about the dirty landlords, and how they rob us poor tenants,” one Pointe Coupee activist stated, “When I heard about this union and what it was for, I joined it and I am proud to be a member of the Farmers’ Union and I am willing to help every good effort for our justice and rights.” Another member wrote, “When our Creator brought us into this world, He gave each and every man a right to inherit some of land that He created. I'm looking to the Union to open the door for me.”64 With the power of organization behind them and with the help of sympathetic federal officials, union members gained some limited concessions from plantation owners in the 1930s.

A key issue that had always concerned rural African Americans was gaining fair settlements at the end of the crop seasons. According to Clyde Johnson, one of the first things sharecroppers and tenants wanted was “a way of having a voice. They wanted their account with the landlord to be on paper.” The LFU taught its members how to keep records of purchases from plantation stores so that they would know if planters tried to cheat them. At the same time, the union lobbied to make the provision of written contracts with employers a standard practice under federal farm programs. Although administrators had always encouraged the use of contracts, they were not compulsory. In 1938 the FSA announced that it would insist on having written leases drawn up between its clients and their landlords, attempting to pacify planters by saying that this was for the protection of both parties. “We know from experience that both profit from having their agreement in written form,” an FSA official stated. Another supervisor explained, “The landlord must be protected against abuse of the land and improvements, abandonment of crops and the like, while the tenant must have assurance of occupancy, a fair division of crop proceeds and renumeration for improvements made.” These statements aside, most of the provisions on the FSA's standard lease form seemed designed to improve conditions for tenants, including minimum requirements for the quality of housing and a guarantee that renters be allowed to follow a live-at-home program.65

Complementing the campaign for written leases, black people used their union locals to continue the struggle for decent schools. Shortly after his arrival in Louisiana, Clyde Johnson reported: “The Negro people, contrary to the teaching of the landlords, are very hungry for education and culture. Union members are already writing to the state depart[ment] of education explaining that they get only 3 or 4 months schools with very poor fa[cil]ities and insisting that they be given longer and better school terms.” In a resolution calling for resettlement loans for the evicted sharecroppers of St. Landry Farm, LFU Local 2 also demanded “better equipped school houses and free text books, longer school terms, higher salaries for Negro teachers, and free transportation for Negro children.” A few months later the Southern Farm Leader reported that a group of union women in the parish had successfully lobbied for improvements at their children's school. The women raised $15.50 for the purpose themselves, then sent a delegation to request more aid from parish officials, who agreed to match the amount. The money was used to install new toilets, new steps, and a fence to enclose the school grounds.66

Union members in other communities carried out similar activities, often making education a top priority. In 1937 the secretary of a newly established local reported, “Our first demand is for a school bus, some of the children have as much as 5 miles to walk.” The following year, when the LFU endorsed the Harrison-Fletcher Bill providing for federal aid to education, one member told Gordon McIntire, “I saw in the Bulletin where you said you had been to Washington to get aid for rural schools. To my judgement that is one of the most important things you could have done for us especially in West Feliciana Parish. . . . I can see and understand that you are on the job and I pray that you and all others keep working for improvement.”67

The LFU also attempted to give members a voice in the administration of federal farm policies. In 1937 Gordon McIntire represented the union at hearings held by the President's Committee on Farm Tenancy in Dallas, Texas. He joined three representatives of the STFU in urging the federal government to allocate more money to its rural rehabilitation programs so that assistance could be given to the thousands of farm families who needed it. A common complaint among rural poor people was that agents of the federal government's Agricultural Extension Service often failed to address the needs of small farmers, tenants, and sharecroppers. “County agents are chosen by the landlords to be of service to the landlords,” an article in the Southern Farm Leader explained. “Its hard for a square dealing County Agent who wants to be of service to share cropers and tenants and small farmers, to keep his job. He is soon fired by the landlords.” The newspaper encouraged readers to demand that county agents be elected by white and black farmers and farmworkers so that they might be more responsive to the needs of the majority of rural people instead of serving the narrow interests of plantation owners. Administrators of federal loan programs also came under attack for discriminating against African Americans and LFU members. Union leaders urged members to write to the heads of government agencies and their representatives in Congress to ask that administration of the programs be placed in the hands of committees elected by all the farmers in the areas they served.68

These efforts to democratize federal agricultural policy and increase black people's political influence were largely unsuccessful.69 At the local level, however, union agitation gained access to New Deal programs for black farmers who otherwise would have been excluded. A measure of the LFU's achievement in this area is that in Pointe Coupee Parish, where the union had many strong locals, more than 80 percent of FSA clients in 1937 were black.70 Union leaders disseminated information about federal loans that were available and helped members to complete the application process. Black farmers who encountered discrimination from local officials could call on the LFU to assist them in gaining fair treatment. Abraham Phillips, for instance, was repeatedly turned down for an FSA loan by his parish committee because of his “general reputation as a trouble maker and a busy body” (a reference to his union organizing activity). The LFU's persistent appeals on his behalf caused the committee members to relent in January 1942. They finally approved Phillips's application in an attempt to “harmonize the labor situation” in Pointe Coupee.71

African Americans were intensely interested in obtaining credit from sources other than white landowners and merchants. In letters and statements to government authorities, black farmers often expressed the belief that all they needed was a chance to prove their ability free from the constraints of exorbitant interest rates and the dubious accounting practices of landlords.72 This theme permeated the affidavits collected by Gordon McIntire during the struggle to gain resettlement loans for the sharecroppers of St. Landry Farm. Almost all of those threatened with eviction wanted to buy the land they worked and believed that they would be able to support themselves if they could borrow money at reasonable interest rates. Harry Jack Rose summarized the prevailing view when he stated, “If I can just have the chance I sure would like to buy this farm. . . . I know how to work and I have eight children and four good hands. I can work 40 acres or more. If I can get a little piece with the government I know I can defend myself.”73

African Americans’ faith in their own abilities was borne out by the experiences of many of those who did receive federal assistance. The first black farmer to pay back an FSA loan did so thirty-six years ahead of schedule. Over all, in the six years following the creation of the first rural rehabilitation agencies, the number of farmers who defaulted on federal loans amounted to only 2.6 percent of borrowers. As one study pointed out, a major achievement of the government's lending programs was the “liberation of the negro and white tenants from bondage to the ‘furnish’ system under which tenants paid an average of 20% to 50% for production credit and were consequently kept in perpetual debt—or perpetually in flight from unpaid obligations.”74

Breaking the strangleholds of expensive credit and permanent debt allowed for great improvements in the lives of some African Americans. Between 1935 and 1937 FSA farmers in Pointe Coupee Parish increased their average net worth from $108 to $567.75 Rehabilitation loans enabled people to achieve a higher standard of living, with many black clients building “houses of the most modern design and with all the conveniences of a city home.” Some tenants became landowners, helping to reverse the trend from farm ownership to tenancy that had been the pattern in the previous three decades. Between 1935 and 1940 the proportion of black farm operators in Louisiana who owned part or all of the land they worked rose from 15 to 19 percent. Noting a similar increase in Tensas Parish, black extension agent J. A. M. Lloyd predicted, “With the present programs of the Federal Government continuing to exist . . . within the next ten or fifteen years every colored farmer in Tensas Parish will be well established on his own farm.”76 Such pronouncements were not very realistic, but the federal government's tenant loan programs nonetheless gave recipients cause for optimism. In 1938 an LFU member expressed these feelings in a letter to the union newspaper, saying, “My crop is coming along fine. With the aid of God and the F.S.A. I hope to establish a better home for myself and family and to help my fellow brothers.”77

The same developments that held such promise for rural poor people elicited negative and sometimes violent responses from their employers. Union organizers’ initial hopes of operating free from harassment in Louisiana were not realized. After its early successes in the mid-1930s, the LFU encountered increasingly strong opposition from white landowners, politicians, and business people in the rural parishes. Opelousas newspapers accused the union of stirring up “class hatred” and turning “the negro against the white man, the sharecropper against the land owner.” Planters tried to discourage farmworkers from joining, claiming that the LFU only wanted to exploit them. One member reported: “Ed B. went to his boss’ office to get $2. that Mr. H. owed him. Mr. H. told Ed., ‘Now don't take this money and give it to that Union because you are only making some fellow rich in New Orleans.’”78 Another landlord called all his workers together one morning and told them not to join the union or there would be trouble: “You fellows going around writing to the government, it will be too bad. And anyone of you who joins that thing, you will have to move.” Gordon McIntire encountered intense hostility from planters, merchants, and local officials whenever he ventured into the rural parishes. One man told him, “We don't want a Union here. . . . We'll keep it out . . . with our lives if we have to.”79

As always, plantation owners could rely on law enforcement officers and other public servants to protect their interests. One night Sheriff D. J. Doucet of St. Landry Parish visited the secretary of the LFU's Woodside local, threatened him, and gave him five days to leave the parish. In 1940 union members in Natchitoches Parish reported that “the landlords are telling the sheriff and deputies to visit all the meetings of the farmers and beat the people until they break up the unions.” Police in the parish held and interrogated one black sharecropper for two hours, telling him that it was illegal for people to pay any dues to the union. Local administrators of federal programs also discouraged farmers from joining the LFU by withholding aid from members. Resettlement Administration officials in Pointe Coupee Parish relocated those who had joined the union to poorer land, took their equipment away so that the farmers had nothing to work with, and held up their AAA checks. The secretary of one local in the parish complained, “The landlords are bitterly against the union in this section,” and added, “Resettlement and county agents are carrying on the same crooked work against us.”80 The danger posed to organizing efforts by the frequent overlap of planter and public authority was most clearly revealed in Rapides Parish during the struggle over sugar workers’ wages in 1939. According to Gordon McIntire, immediately after wage claims were submitted to the local agricultural committee, “terror broke out in Rapides Parish, where one of the big landlords against whom we had entered several claims, was Chairman of the Parish Committee.”81

Union members lived with constant threats of evictions, beatings, imprisonment, and death. One man who dared to ask his landlord if his AAA payment had arrived reported that his employer “seemed to get offended because I asked about my check, and he told me I had been with him too long for him to hurt me, so I had better move before he killed me. And he gave me 24 hours to be gone off the farm.” In June 1937 a group of white men broke into the home of Willie Scott in West Feliciana Parish, seeking to lynch him. Finding only his wife Irene, they beat her severely in an attempt to gain information. Irene Scott survived by pretending to be knocked unconscious and fleeing to some woods while the men waited outside the house for her husband to return. With the help of other union members, the Scotts escaped to New Orleans. Frightening attacks like this were common. By the late 1930s most LFU members probably felt a lot like Joe Beraud, who feared that he would soon be murdered by his landlord. “MR. WARREN is going all around telling both whites and blacks that he is going to kill me,” he wrote in a letter to Gordon McIntire. “He is carrying his gun for me. . . . My life has come to be like a rabbit's.”82

Black Louisianans who had joined the LFU in the hope of achieving better living and working conditions struggled determinedly against plantation owners’ attempts to repress their efforts. African Americans in Woodside responded to the threats made against their union secretary by forming an armed guard to watch over his home and family. Communist organizers supported the right of black people to protect themselves against violence and encouraged the use of armed self-defense. In a letter to LFU members during the St. Landry Farm fight, for instance, Gordon McIntire wrote, “If any members house is threatened by crazy hoodlums they have a right to protect their home with guns. We are not going to make trouble but must protect our rights.”83 A 1937 report on the situation in West Feliciana Parish noted that “some of the negro union officers were quite capable of determined, courageous and effective leadership and quite competent to take care of themselves in a test of strength with the whites.” Despite planters’ attempts to kill them, Willie and Irene Scott returned to the parish and continued their union activities. The LFU newsletter reported in February 1938 that members in West Feliciana had “bandaged up the victims and dug deep into their pockets for food and other aid,” and that the parish locals remained strong even though they could not meet as openly as before. “Maybe poor folks just don't have good sense,” the report stated, “but when other people are getting shot at, poor folks want to know why. And so more people join up and the Union rocks on, for Union men are hard to scare.”84

The LFU's ability to call on federal assistance in the 1930s might have contributed to its members’ tenacity. After Gordon McIntire had complained repeatedly to government officials, both the Department of Agriculture and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) finally sent investigators to the sugar parishes in 1939.85 In its September newsletter, the LFU assured members that government officials were “determined to investigate every case of intimidation or any other violations of civil liberties.” Although this statement greatly exaggerated the Roosevelt administration's commitment to ensuring justice in the sugar parishes, the mere presence of the federal agents had a positive effect. The interest that events in rural Louisiana attracted from people outside the region threatened to undermine the tight control that planters had over their communities. Consequently, they sought to avoid actions that might provide material for sensational headlines in northern newspapers or draw national attention. Fear of federal intervention prevented officials in Natchitoches Parish from lynching Clinton Clark after he was arrested and jailed there in 1940. According to one account, there was every likelihood that Clark would be killed until the state attorney general made a telephone call to the parish district attorney. “No—no lynching!” he reportedly stated. “We've got to be careful. The State is on the spot. Can't afford that kind of thing with the federal government like it is.”86 Violence continued in Natchitoches and other parishes where the union was active, but the situation almost certainly would have been worse had it not been for the contacts that the LFU had established with officials in Washington.

Southern political and economic leaders deeply resented the encroachment of national authority into local affairs. Although they welcomed efforts to stabilize agricultural prices and benefited greatly from the AAA, planters viewed any attempt by the federal government to address more fundamental issues of poverty and inequality with suspicion. Plantation owners had been wary of the New Deal from the time of its inception, and they grew increasingly uneasy as the decade progressed. The new federal presence in the South and the encouragement that liberal officials in Washington provided to organizations like the LFU threatened the existing social order. In the early 1940s southern lobbyists joined forces with conservative northern business leaders to demand an end to the government's “socialistic” experiment.

Much of this opposition focused on the FSA. Critics charged that the FSA's efforts on behalf of poor farmers interfered with natural economic forces that dictated the failure of inefficient or incompetent enterprises, that its encouragement of cooperative farms was “communistic,” and that attempts to combat the high incidence of disease among its poverty-stricken clients risked introducing “socialized medicine” into the United States. The agency was vilified in country newspapers and at mass meetings of plantation owners throughout the South, and enemies of the FSA in Congress succeeded in passing budget amendments in 1940 that restricted appropriations for its tenant loan program. At its annual meeting in December of that year, the powerful AFBF called for the abolition of the FSA and the transfer of federal loan programs to the Agricultural Extension Service, whose agents generally supported the interests of large producers. Although the FSA officially survived until its replacement by the Farmers’ Home Administration (FaHA) in 1946, its activities were sharply curtailed after 1942 by further budget cuts and the shifting of many of its responsibilities to the Extension Service. After the reorganization of the government's farm credit agencies, assistance was denied the majority of poor farmers who applied for loans. The displacement of plantation workers continued with little to cushion the effect, relegating many people to the status of seasonal wage laborers forced to work for low pay during the harvest seasons and dependent on public welfare services at other times of the year.87

At around the same time, the fortunes of the LFU began to decline. After reaching a high point of about three thousand members in 1940, both membership and finances decreased dramatically over the next several years.88 Organizing efforts had always been hindered by widespread poverty among the people the union sought to recruit. Most rural families could barely afford to spare even the meager amount it cost to join the union, and the LFU had many members who paid their dues irregularly, if at all. The union was therefore heavily dependent on donations from liberal sympathizers to finance its activities. Those funds became harder to obtain as the United States prepared to support the European democracies in World War II, a move that most liberals supported, while the Communist Party and union leaders advocated American neutrality and attempts to resolve European problems peacefully. In June 1941 one staff member wrote of the difficulties the LFU was experiencing in raising funds from former benefactors, saying, “the war has changed the attitudes of ‘liberals’ who once contributed liberally. . . . Try to appeal to the [deleted words] today! There's a red bogeyman hiding behind everything except a defense poster.” Later that month Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union prompted an abrupt switch in the party line, but the transition to all-out support for the war only further weakened the LFU, as activists shifted their attention from the rural South to the fight against fascism overseas.89

The union also suffered from the loss of two of its most experienced organizers. Gordon McIntire contracted tuberculosis and was forced to give up work in January 1940. He left Louisiana six months later, and Peggy Dallet shortly followed. Two other staff members, Roald Peterson and Kenneth Adams, attempted to keep the New Orleans office functioning, but insufficient funds and continued repression by plantation owners hindered their efforts. Failure to collect annual dues in the fall, the only time most rural workers had any cash, left the LFU with only one paid-up member on record in 1941. Peterson and Adams found themselves in an impossible predicament, lacking money because they were unable to visit union locals to collect it and unable to visit locals because they had no money. The union's financial difficulties resulted in the suspension of its state charter by the NFU in December. Concordia Parish officials took advantage of the situation to arrest Adams and Clinton Clark for “collecting money under false pretenses” when they ventured into the parish on a fund-raising trip in January 1942. The two organizers were not released for three months.90

Meanwhile, the planter-dominated Louisiana Farm Bureau used its influence with the Agricultural Extension Service to encourage rural people to join the bureau instead of the LFU. Extension agents printed and distributed notices of farmers’ meetings, promoting the Farm Bureau as an organization that had close ties with the government and could do more for farmers than other agricultural unions. An additional “advantage” for poor sharecroppers and tenants was that their landlords were often willing to pay Farm Bureau dues for them.91

Developments during World War II also contributed to the demise of the LFU. New economic opportunities drew thousands of rural people to the cities, where they worked in factories for wages that were higher than they could ever hope to earn as farmers. Wartime prosperity and the increasing demand for labor offered an easier solution to farmworkers’ problems than remaining on the land and fighting plantation owners. Many of the LFU's rural constituents drifted away, either migrating to urban areas or moving into nonagricultural employment.92 In March 1942 Gordon McIntire wrote a circular letter to LFU members from a Denver sanatorium urging them to continue their union activities while organizers worked to collect enough dues to have the state charter restored, but his appeal failed to halt the disintegration of the union. Although a few locals continued to hold meetings and recruit members, the LFU was not rechartered, and there is no trace of official union activity after the mid-1940s.93