6 I Am an American Born Negro:

Black Empowerment and White Responses during World War II

Though studies of the civil rights movement generally acknowledge the ideological and economic significance of World War II, the early 1940s have not received nearly the same amount of attention from scholars as the postwar period. Existing histories mostly focus on the activities of national leaders and organizations and the ways they used the war to pressure the federal government to implement antidiscrimination measures.1 Yet the actions of black activists in Louisiana reveal that the freedom struggle was just as intense at the local level.

The war brought dramatic changes to the rural parishes. Once again thousands of black people left the region to join the armed forces or to seek industrial employment in urban centers both within and outside the state. Higher incomes and liberation from the control of planters enabled African Americans to launch some powerful offensives against white supremacy during this period. Adopting the slogan of the “Double V” for victory over racism at home as well as abroad, black people worked to bring freedom, equality, and justice not only to the occupied nations but to their own country as well. Newspaper editors and civil rights groups highlighted the contradiction of fighting for democracy overseas while allowing segregation, disfranchisement, and violence against black people to continue in the United States. Soldiers and defense workers protested discrimination in the armed forces and war industry employment. White Louisianans responded by attempting to force their former farm laborers and domestics back into subservience, but they were unable to reverse the massive changes brought about by the war. After World War II, neither the South nor the nation would ever be the same.

As the threat of war in Europe loomed in the late 1930s, the Roosevelt administration worked to support the western democracies and prepare the United States for possible intervention. By this time many people, including former pacifists, were convinced that taking up arms was the only way to prevent the further expansion of Nazi Germany. But others remained unconvinced that events taking place in a far-off continent could have any relevance to themselves. Given their experiences in the aftermath of World War I, African Americans were understandably ambivalent. In 1936 a tenant farmer in St. Landry Parish expressed a common view among black people when he stated: “The only thing that made me sorry was when the world was in war before. They picked us up and registered us and sent us to war to fight for our country. Now the country is quieted down and steady and the government doing with us just like a man would do with an old poor dog. If they was going to fight again we would sit right here.”2

Although many black Louisianans eventually supported the war effort, many also continued to voice suspicion and mistrust. In May 1940 a group of black newspaper editors and business leaders in New Orleans warned President Roosevelt that the “un-American practices against the Negroes of this state” were having a detrimental effect on black people's willingness to participate in defense preparations. Some African Americans had “shown evidences of revolt against anything sponsored by the officials of this state for the promotion of the Defense Program,” they said, and were “advocating non-cooperation and rebuke to the fullest extent.”3 The federal government's own regional analyst in Louisiana, Edgar Schuler, also reported widespread dissatisfaction among the state's black residents. As he put it, “The dumbest plantation Negro can't see why he should fight to save Germans from Hitler when he has a Hitler right over him on his plantation.”4

Accounts such as these caused much consternation at the Office of War Information (OWI) and other federal agencies responsible for monitoring and directing public opinion about the conflict. Throughout the war government officials kept a close watch on African Americans, assigning bureaucratic armies to tasks such as scanning black newspapers and magazines, visiting the headquarters of civil rights groups, gathering and analyzing information from around the country, and conducting special investigations to assess the state of “Negro morale.” The Chicago Defender did not exaggerate when it reported that administrators in Washington could hardly wait until Thursday of each week to “grab a ‘Negro paper’ and find out how the wind blows.”5 In June 1942 FBI director J. Edgar Hoover commissioned a special survey on racial conditions in the United States to assess the threat of subversive activity among the nation's black citizens.6 The reports that resulted from these efforts often concluded the obvious: to gain African Americans’ wholehearted support for the war, it was necessary to eliminate discrimination—at least in the armed forces, civilian defense training, and industrial employment, if not in all aspects of American life.7

African Americans did not wait patiently for state and national political leaders to grant them these things. As during World War I, hundreds of thousands of black people left the South to seek better jobs and living conditions elsewhere.8 Louisiana's net gain in black population between 1940 and 1950 makes it difficult to tell exactly how many black Louisianans left the state during this period, but census data for individual parishes provide some indication of the extent of black migration from the various regions. All but four of the cotton plantation parishes reported decreases in their black populations ranging from 4 to 31 percent. Seven of the thirteen sugar parishes also lost some of their black residents, with the parishes located near Baton Rouge losing the most. At the same time, parishes with cities of ten thousand people or more gained in black population at an average rate of 26 percent, suggesting that many African Americans left the countryside to seek new jobs in urban areas. (See Table 6.1.) A notice that appeared in the Madison Journal in May 1943 is also revealing. Out of thirty-five local black men who were called to military service that month, only six still resided in Madison Parish. Nineteen of the missing men had moved to either California or Nevada, one had gone to Chicago, and the remaining nine were living in cities in Louisiana or in other southern states.9

The armed forces provided black Louisianans with another avenue of escape from the plantations. Reservations about sacrificing their lives for an imperfect democracy aside, joining the military offered opportunities for training and employment that few black people could have gained otherwise. In 1940 pressure from national civil rights groups persuaded Congress to include prohibitions on discrimination in the Selective Training and Service Act, raising hopes that African Americans might be treated equally in the selection and training of military personnel. In April the following year, the Madison Journal reported that many black men in the parish had eagerly signed up for service. “Several colored citizens here remarked during the week that if another trainload of negro soldiers passed through Tallulah, there would not be a young negro left,” the article stated. So far the local draft board had managed to fill all of its black quotas with volunteers and had a waiting list of fifty men.10

With the creation of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corp (WAAC) in May 1942, the possibility of military service was also opened to black women. Recruitment officers for the WAAC and its successor, the Women's Army Corp (WAC), toured Louisiana in 1943 and 1944, encouraging women to join up through appeals to their pocketbooks as much as their patriotism. The WAC offered women a fifty-dollar-per-month salary plus free housing, meals, uniforms, and medical care, along with the chance to train in a variety of careers. Courses to prepare them for jobs as clerks, stenographers, bookkeepers, typists, airplane mechanics, radio operators, and chauffeurs were among those on a list that one officer stated “would fill a college catalogue.”11 African Americans who served in the military often achieved levels of education, skills, and economic security that were unheard of among rural black people, in addition to being exposed to new people, ideas, and social settings outside their home state.12

For black people who remained in Louisiana, defense preparations created new employment opportunities. Early in 1941 construction work began on several military training camps and airports in northern and southeastern Louisiana. In April, state employment analysts reported that landowners in the region were having difficulty finding tenants and day laborers, since many farmworkers had abandoned the plantations for the higher wages they could earn on construction projects. Only a handful of these people returned to their former employers when the building boom ended. J. H. Crutcher informed WPA officials in Washington that “because of the great difference between the rate paid farm labor, from $.75 to $1.50 a day, and that of $3.20 paid at the camps, many are putting off accepting employment or seeking reinstatement on W.P.A. because of their hope that further work, such as the cantonments, will develop.” Over the next few years new shipbuilding and ordnance plants located in Baton Rouge, Shreveport, Lake Charles, and Erath continued to act as magnets for farmworkers from the surrounding parishes, exacerbating the problems of planters but greatly increasing the economic prospects of the African Americans employed in them.13

Black people who continued to work on the plantations also benefited from

the war. Competition for labor forced planters to raise wage rates and offer tenants more appealing work contracts. Anticipating as much, Congress extended the Sugar Act for three years past its initial expiration date of December 1941 and gave growers a 33.5 percent increase in subsidies to enable them to match the wage scales offered by other employers. Consequently, minimum wages for adult male sugarcane cutters rose from $1.50 per day in 1941 to $1.85 in 1942. The following year, many growers found it necessary for the first time to pay more than the minimum rate determined by the Department of Agriculture, increasing average wages during the harvest season by approximately 46 percent. Observers recorded similar increases for day laborers in the cotton parishes.14 A study conducted in 1943 noted that because of the demand for personnel in industry and the armed forces, “Even the farm laborer and migratory worker are being comparatively well paid for the first time in their lives.” In 1945 Louisiana reported a farm wage bill of $30,102,470, an increase of 107 percent over the $14,546,990 paid to agricultural workers in 1940.15

The need to raise agricultural production to levels sufficient for feeding

African American company of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps in training at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, May 1943. Service in the armed forces and their auxiliaries did not insulate black military personnel from discrimination or persecution during World War II, but it did offer a measure of economic security as well as training opportunities that most African Americans had not previously had access to. RG 111-SC-238651, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

European allies as well as Americans once again resulted in the expansion of the Agricultural Extension Service. Funds allocated by the War Food Administration enabled the states to hire more African American agents to work with black farmers, and a nationwide “Food for Freedom” campaign exhorted all rural families to grow their own food so that more would be available for domestic and foreign consumers.16 Louisiana administrators announced plans to contact every farmer in the state, promising to provide all the assistance that was available from the various farm agencies to those who agreed to cooperate with the program. Pointe Coupee Parish extension agent A. B. Curet declared, “This is the finest opportunity we have ever had to achieve a balanced agriculture, increase our income, improve our standard of living, make our farms better farms and at the same time aid national defense.” After visiting Louisiana and several other states in 1942, two

Black laborers awaiting transport to a construction project in Camp Livingston, Louisiana, December 1940. Defense preparations created new jobs and lured thousands of rural people away from the plantations even before the United States officially entered World War II. LC-USF34-56690-D, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

officials from the Department of Agriculture reported that landlords who had formerly prevented workers from growing their own food were now “encouraging and occasionally requiring their tenants to grow a variety of foodstuffs.”17 Landowners risked being labeled unpatriotic if they refused to allow tenants and sharecroppers to cultivate “victory gardens.” Wartime exigencies therefore forced planters to concede on issues that had long concerned black people in their struggle for economic independence.

African Americans’ new prosperity fueled an increase in civil rights activity during the war. At the same time, wartime rhetoric and the government's need to unite people behind mobilization efforts provided black Americans with powerful leverage in the fight against injustice. A special issue of the black New Orleans newspaper Sepia Socialite published in 1942 was filled with references to the dual meaning of the war for African Americans. In one article, Bishop S. L. Green wrote, “the Negro marches on with America, but not blindly. When he defends the United States of America abroad, he does not want to be disenfranchised and unjustly treated at home.” In a foreword to the work, George Schuyler urged black Louisianans to take advantage of the war to demand equality. “Let them resolve that not only will they enjoy democracy and freedom AFTER this great world struggle is over, but that they must have them HERE and NOW,” he wrote. “Let them insist with all the force and eloquence at their command that for them democracy must begin AT HOME, in Louisiana, and that they want it to begin AT ONCE.”18 Staff at the FBI's New Orleans Field Division reported that the state's other black newspapers had adopted a similar tone. According to these agents, African American editors and publishers were conducting “a militant campaign for equal rights as well as those against social, economic and political discrimination” and often exploited the war situation to threaten the withdrawal of black people's support if conditions did not change.19

Civil rights organizations like the Urban League, the NAACP, and the newly formed March on Washington Movement (MOWM) engaged in similar campaigns. The NAACP increased its presence in Louisiana during the war, with local activists managing to charter more than thirty branches by the end of 1946. The strongest chapters were in urban areas like New Orleans and Baton Rouge, but the organization also reached into Iberville, Concordia, Madison, St. Landry, and other rural parishes.20 In the early 1940s the NAACP worked with the Louisiana Colored Teachers’ Association (LCTA) and local civil rights groups to pressure school boards to equalize white and black teachers’ salaries. African American leaders used the rhetoric of the nation's war propaganda to argue the case for justice. In April 1943 the Iberville Parish Improvement Committee presented a petition to school board officials that stated, “We approach this problem in the Democratic way—the way for which our sons and other loved ones are sacrificing their lives on foreign battle fields with the hope that this honorable body will deal with the matter in the American spirit of fair play, granting to the Negro teachers their appeal for equal pay for equal work.” Two months later LCTA president J. K. Haynes warned Governor Sam Jones that the state might soon suffer from a shortage of black teachers unless they were treated fairly. “Many of our teachers are leaving the profession going to defense area and other high salaried positions due to inability to make a living wage teaching,” he observed. “We humble urge that you use your influence to the realization of equalization of economic opportunity in the teaching profession in this state which is in keeping with the American ideal of democracy.”21

Working-class black people made up a large proportion of the NAACP's membership, and they were also vital participants in the March on Washington Movement.22 As government analysts noted, the MOWM's focus on gaining equal job opportunities for black people held enormous appeal to thousands of African Americans. One report explained: “It is in regard to job discrimination that Negroes feel the deepest rancor. They recognize that economic opportunity is the basic remedy for all of the injustices which they suffer. They are distressed by social discrimination, by segregation, by the unfortunate living conditions imposed upon them and by other disadvantages. But interviewing indicates that their prime concern at present is over their economic handicaps.”23 In war industry centers like California's East Bay area, migrants from the rural South strongly supported the NAACP's and the MOWM's organizing efforts. There and in other cities across the nation, former tenants and sharecroppers who joined the industrial working class continued their struggles for economic independence and political influence, pursuing long-standing goals in new contexts with new methods. The threat of mass demonstrations if the government failed to act against racism persuaded President Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in June 1941, banning discrimination against black workers by unions and employers who held government contracts and creating the President's Committee on Fair Employment Practice (FEPC) to monitor the hiring procedures of companies.24

Although lack of resources and opposition from business leaders and conservative politicians hindered the FEPC's work, the government's ostensible commitment to equality encouraged black people to assert their rights and made them more likely to protest discrimination. In February 1944 two thousand African Americans employed at the Delta Shipbuilding Company in New Orleans went on strike after some of the plant's white guards harassed and assaulted several black workers. The walkout lasted for a day and a half while FEPC staff members tried to negotiate a settlement to the dispute. The company's managers eventually agreed to fire those responsible for the attacks and to hold weekly meetings on racial issues with supervisors and superintendents in an attempt to avoid further conflict. An FEPC report on the incident noted that in this time of national crisis, it was becoming more difficult for white people “to terrorize and keep the Negro in his place, for his cooperative effort in the production of ships is vitally needed.”25

Often, black Louisianans’ petitions to the FEPC's office in New Orleans reflected a new sense of empowerment. Their letters expressed both indignation at the abuses they suffered and the belief that the government should and could do something about them. Laundry worker Lena Mae Gordon reported from Camp Claiborne in Rapides Parish that her supervisor had said that she would rather resign than recommend a black woman for a raise. Gordon stated, “I want to know why we don't get a raise? . . . I am willing to work on any defense job but I want to be treated justly. They say we are ignorant but this is not so. . . . I am an american born Negro and willing to do any thing to help my country but I WANT JUSTICE.” Some letters slyly manipulated official concerns about maintaining black people's support for the war. For example, when clerical worker Edith Pierce wrote to complain of an “atmosphere of under-cover hostility” toward her and the other African American employees at the Port of Embarkation in New Orleans, she ended by saying, “This letter is written with the expectation that something might be done toward improving the morale of one who would enjoy all the privileges of American Citizenship in full.”26

Being asked to contribute to the defense of democracy overseas while suffering decidedly undemocratic treatment in the United States naturally sharpened black Americans’ resentment of injustice. Such feelings were especially intense among those who were drafted or chose to serve in the armed forces. As newspapers, government reports, and civil rights activists pointed out repeatedly, the treatment of black military personnel by their commanding officers and white civilians was a national disgrace. African Americans served in segregated units and were often assigned to unskilled work regardless of their qualifications. Dining and recreational facilities provided for black servicemen and women were invariably inferior to those of their white counterparts. Discipline was stricter on their side of the Jim Crow line, with African Americans routinely suffering harassment and sometimes violence at the hands of white military police and local law enforcement officers.27

Conditions for black personnel stationed in Louisiana were abysmal. African Americans at Camp Polk reported that the white civilians who ran the canteen refused to sell food to black people and stated, “Colored soldiers at this camp are treated like dogs.” Black technicians assigned to Camp Clai-borne spent most of their time performing menial tasks far below their skill level. Edgar Holt complained, “After spending months in school being trained to do specific jobs we land in labor battallions while our skills go to waste. Our assignments are permanent K.P., supply and other details.” George Grant considered the treatment of African Americans at the camp to be “on a par with the worst conditions thru the south since eighteen sixty-five.” White officers called them “niggers,” their pay checks often arrived late, and they frequently suffered rough treatment by military police who resembled “nothing so much as a deputized Dixie mob.” A resident of Camp Livingston expressed similar sentiments. In meting out punishment to black servicemen, he stated, white officers were “just like a lynch mob with a neggro to hang.”28

Many African Americans did not suffer such treatment quietly. A group of WACs stationed at Camp Claiborne made their resentment known to their commander, who complained that the women seemed “dissatisfied with their assignments and treatment,” that “most of them had a bad attitude,” and that “they are race conscious and feel that they were being discriminated against.”29 Black servicemen and women petitioned federal agencies and civil rights organizations protesting discrimination and highlighting the contradictions between the government's war propaganda and its practice. Writing to the War Department about her experiences with white bus drivers in Alexandria who repeatedly refused to let her ride even though she “had on the same government uniform that the white soldiers wear,” Dorothy Bray asked, “Why? Why are we here, I am sure none of us asked to be born but since we are born, don't we have the right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness, even when the color of our skin is dark?” A black man stationed at an army air base near Baton Rouge made a similar argument. “Owing to the fact that we are Negro soldiers of the American Army and fighting for the same cause as the White Soldiers,” he wrote, “we expect and feel that we should have just treatment due an American Citizen and an American Soldier, who has sworn to protect and defend this country from such practices as are exercised in this particular camp.”30

Both soldiers and civilians in Louisiana also engaged in direct action against injustice. Immediately after arriving at a train station in Sabine Parish, black sergeant Nelson Peery spat on the “White” and “Colored” signs that designated the separate waiting areas, and another member of his division knocked them down with his rifle butt. Segregated seating arrangements on public transportation provided one of the most frequent areas of contestation in Louisiana and other parts of the South. White bus drivers and riders were stunned to discover that African American servicemen and women believed that their uniforms gave them the right to sit anywhere they liked.31 Altercations between white Louisianans and black military personnel became so frequent that the commanding officer at one camp issued a special memorandum reminding African Americans of their second-class status. “The Louisiana law prescribes that white people riding conveyances shall take seats from the front of conveyance toward the rear and colored people from rear of conveyance toward the front,” the order stated. “This law also applies to Military Personnel. . . . In the event that operator of public conveyance request[s] Military Personnel to move toward the front or the rear they will occupy seats assigned to them by the operator without argument.”32

The presence of black soldiers and defense workers from other parts of the country created opportunities for local black people to engage in their own subterfuges against the social order. An officer stationed at Harding Field near Baton Rouge told Edgar Schuler, “Sometimes you get a case like this: a boy who claimed he was from New York, after he had got into some difficulty, turned out to be from the South. They say they aren't used to conditions as they find them in the South.” Some African Americans engaged unapologetically in blatant acts of defiance. “They think they're as good as we are right now,” one white Louisianan complained. “Some of em don't even move off the banquette (sidewalk) to let you pass, or on the side even.” Other white people cited the “high and mighty ways displayed by previously apparently docile colored girls and women” as a constant source of annoyance. Dozens of similar comments and quotations filled Schuler's weekly reports, indicating that many black people were no longer willing to conform to their expected roles. By April 1943 law enforcement officials in all but one Louisiana parish had reported having some kind of trouble with “uppity” African Americans.33

White people deeply resented the loss of servility that seemed to be infecting the state's black inhabitants. But it was not so much disrespectful behavior as the disappearance of their cheap labor supply that upset them the most. Many of the concerns they expressed about the impact of the war on black people centered on the economic gains that African Americans had made and their unwillingness to perform menial tasks now that alternatives were available. “This terrible war has made some big changes with us, and our mode of life will be even more changed before it is ended,” a resident of Tangipahoa Parish fretted. “The negroes just won't do domestic work—so we are still without a cook, or servant of any kind.” Analyzing the sources of increasing tension between white and black people in the state, Edgar Schuler noted that a major factor was the “improved economic status of Negroes . . . and resentment by whites at scarcity of domestic help.” Most people recognized that even when the fighting was over, African Americans would not willingly return to the positions they had occupied before the war. The entire southern social order was being contested, and white people knew it. According to Schuler, local authorities avoided discussing or drawing people's attention to these matters, but there was “a great deal of private talk consisting of rumors, stories, gossip, threats, and boastings—all or largely from the point of view that ‘we'll teach the damn’ nigger to keep in his place.’”34

Throughout the war, white Louisianans made plain their unwillingness to tolerate attempts by African Americans to gain equality. During the initial phases of defense preparation, state and local officials made only token efforts to train black people for industrial jobs. Federal investigator John Beecher reported in March 1942 that Louisiana had a thriving defense training program that offered participants the chance to acquire, at public expense, the skills that would eventually enable them to obtain well-paid work in the region's new shipbuilding and munitions plants. However, he noted, “From this program of free public instruction Negroes have been excluded almost completely, and solely by reason of their race.” Educators responsible for the programs said that they would gladly include African Americans but their local defense councils refused to provide the necessary funds; state and local officials argued that it was a waste of taxpayers’ money to train black people for defense jobs because companies refused to hire them; and employers claimed that they were willing to hire black workers but feared strikes and other negative reactions by their white employees.35 The arguments went around in a seemingly unbreakable circle, using the results of racist practices to justify perpetuating those same practices.

The efforts of the FEPC went a small way toward increasing black employment in defense industries, but African Americans did not gain access to these jobs in large numbers until the pool of white labor was exhausted. In the spring of 1942, two years after the defense program was established, black people represented only 2.5 percent of Americans employed in war production. By November 1944 the proportion had risen to 8.5 percent, with 1.25 million black workers finding jobs in defense industries. In Louisiana, the number of African Americans employed in all manufacturing occupations rose from 28,909 to 37,995 between 1940 and 1950.36

As some company owners had predicted, white workers did not easily accept the influx of African Americans into new positions perceived to be far above their rightful status. After one WPA administrator arranged employment for ten young black men at a small shipbuilding plant in St. Mary Parish, he learned that “white workers in the yard were bitterly hostile to the idea and were threatening to massacre the Negroes if they were put to work.” Rather than risk their lives, the well-meaning official “whisked his charges unhurt but still unemployed back whence they had come.” In July 1945 workers at the Todd-Johnson shipyard in Algiers went on strike after a black man was hired as a boilermaker's helper. Despite their desperate need for his skills, the company's owners fired the man and reassured white employees that they would not employ African Americans in any positions other than unskilled labor.37

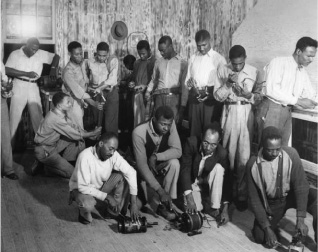

National defense training program, Southern University, Baton Rouge, 1941. Defense training offered the chance to learn new skills and gain jobs in defense industries that sprang up throughout the state during World War II. RG 208-NP-2-R, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Even when the entry of black people into formerly all-white workplaces was achieved peacefully, this did not imply acceptance of their right to equality. Complaints to the FEPC testify to the discrimination, harassment, and threats to their physical well-being that some African Americans faced every day on the job. Edith Pierce's official job title at the Port of Embarkation in New Orleans was “Junior Clerk Typist,” but the amount of typing or other clerical tasks she received was “negligible.” Instead, her supervisors assigned her to “messenger work and errands throughout the area of the Port.” When Joseph Provost asked his foreman about obtaining a position as a tow-motor or tractor operator at the port, he was told that black people could not be employed in those jobs. Provost appealed to the officer in charge of his section, who agreed to allow several black workers to take the tests required for operating the machinery. In response, white operators recruited some white men from outside the port to learn the job and try out the same day. Subsequently, five of the new arrivals and none of the African Americans were hired. One of the white men later told Provost that they had decided to resign “rather than to have Negroes holding the same job as they and getting the same pay with them.”38

While industrial workers sought to exclude African Americans from their terrain, plantation owners attempted to prevent black people from leaving theirs. In 1942 farmers and extension agents in the rural parishes complained of “serious and numerous” labor shortages during the harvest season because of the alternatives to cotton picking and cane cutting that were available.39 As the demand for industrial workers increased, large numbers of black people abandoned rural areas for the army or defense jobs, and the money they sent home to their families enabled others to withdraw from the labor market as well.40 For these reasons, white people in the plantation parishes resented the federal government's efforts to ensure equal opportunities for black people at least as much as those who lived in urban areas. In September 1942 the chairman of the Pointe Coupee Parish Civilian Defense Council complained to Governor Sam Jones that “from the very beginning of our preparedness move certain organized minorities have seized the opportunity to advance their causes, through unheard of wage rate increases and working conditions.” He enclosed a resolution from the parish defense council suggesting that “the government in its struggle for existence should be less solicitous about the social gains made during recent years by a few groups, and exert its unhampered resources to the winning of the war.”41

The same month, representatives of the nation's major agricultural organizations met in Washington, D.C., to devise a coordinated plan of attack against government intervention in the economy and new protections for the rights of workers. Leaders of the AFBF, the Grange, the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives, and the National Cooperative Milk Producers’ Federation discussed ways to defend the “business interests of farmers” from assaults by the Roosevelt “dictatorship.” According to one source, “The general tone of the discussion was . . . that it is necessary for business men and ‘business farmers’ to block further administrative control of American business life whether in the farm, field or any other [area] and particularly to stop administration coddling of labor.”42

Workers on a lunch break at Higgins shipyard, New Orleans, June 1943. African Americans were excluded from most defense industry jobs in the early phases of World War II, but once the pool of white workers was exhausted, employers were forced to hire black labor. LC-USW3-34429-D, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Pressure from this powerful farm bloc persuaded Roosevelt to approve legislation in April 1943 that placed restrictions on the mobility of agricultural workers and empowered the Extension Service to assist in the recruitment of additional labor for those areas that were experiencing shortages. A labor stabilization plan went into effect in Louisiana at the end of that month. Under the new regulations, workers in “essential activities” like farming could not leave their jobs unless they obtained a “Statement of Availability” from their employers, and they could not be hired for new positions unless they produced proof of their release. Though these obstacles were a potential hindrance to black migration, they were not entirely effective. Many farmworkers registered with employment services as truck drivers, mechanics, or other types of laborers without mentioning their agricultural backgrounds, enabling them to slip through the net. In addition, planters in northeastern Louisiana received a nasty shock when federal authorities designated their region a labor surplus area and began transporting workers to places deemed to be in greater need of their services. Congressman Charles McKenzie eventually managed to convince the meddling officials that his district could not spare any labor, and they agreed to stop encouraging workers to leave.43

At the same time, extension agents worked with parish advisory committees to devise local solutions to farm labor problems. Often these efforts involved encouraging or coercing black people to return to the plantations at harvest time to help gather the crops. Louisiana's state supervisor of extension work explained how the system worked in one rural community: county agents enlisted African American ministers to canvass

every colored section of Monroe and West Monroe for six days. . . . The patriotic duty of every American to assist in the war effort was explained to each person visited, together with the need of getting this year's vitally important cotton crop out of the fields as quickly as possible. At first, many of the persons visited were reluctant to give their names as volunteer cotton pickers; others said they were willing to pick, although not physically able. Under the persuasive influence of their fellow-race members, however, reluctance was short-lived. Those who said they were not physically able to go to the fields, changed their minds.

One thousand cotton pickers, mostly women and children, eventually “volunteered” to help with the harvest.44

Although it is possible that the “persuasive influence” of extension agents and civic leaders inspired black workers to perform their patriotic duty, a more likely explanation was that they feared retaliation by white people if they did not comply. Local authorities who seemed unconcerned when white women declined to enter the workforce became incensed at the idea of black women doing the same. In April 1943 Alexandria mayor W. George Bowden invited employers to provide him with the names and addresses of black women who had quit their jobs “for no legitimate reason” and announced that he would force them back to work “or run them out of town personally.” The same year, a report prepared by the Social Science Institute at Fisk University noted an increasing number of incidents of intimidation in the South, mostly involving agricultural and domestic workers. Its authors concluded that threats, violence, and the restrictive legislation embodied in the Farm Labor Program and local work-or-fight ordinances were aimed at forcing black people to continue working for “unwarrantedly low wages.”45

In addition to seeking tighter control over the existing workforce, plantation owners initiated a campaign to import extra laborers into the state. In June 1943 Louisiana's Extension Service administrators reported that they had received “numerous requests as to the possibility of using war prisoners in the harvesting of crops,” mostly from sugar growers. Local farm labor committees succeeded in gaining permission to set up prisoner-of-war camps in Calcasieu, Ouachita, Iberia, Ascension, Jefferson Davis, St. Charles, St. Mary, West Baton Rouge, and Madison Parishes, accommodating nearly four thousand workers. War prisoners were later brought into Pointe Coupee and St. Landry Parishes after extension agents concluded that labor shortages were likely. By 1944, twenty-six prisoner-of-war camps were operating throughout the state. Proponents of the camps insisted that the use of prisoners would not “impair wages, working conditions and employment opportunities or displace employed workers,” but these claims were unrealistic. Planters’ manipulation of the labor supply prevented farmworkers from increasing their bargaining power as much as they might have. As the county agent in Madison Parish reported, the prisoner-of-war camps “stabilized local labor considerably because the local labor knew that the p.ws. were available for farmers to use and if they did not do the job, farmers would get p.ws. to help them out.”46

Though these actions went some way toward alleviating labor problems, agricultural employers remained dissatisfied. Ultimately, many planters adopted the more effective strategies of mechanization and crop diversification, enabling them to operate their plantations with fewer workers. Max McDonald reported from Madison Parish in 1945 that farmers were “becoming mechanical minded since there has been such a severe labor shortage.” Farmers in the parish had not previously shown much interest in new machinery because of an abundance of cheap labor, McDonald explained, but with workers now in shorter supply they had “changed over rapidly from necessity.” Newspapers and extension agents in other parishes noted that the use of tractors for plowing and planting cotton crops was spreading, and that many growers were experimenting with grain and livestock production, two enterprises that required less labor than cotton and were more easily mechanized. By 1950 cotton accounted for only 29 percent of the crop-land harvested in the state, compared with 48 percent in 1930. In the following decade, the proportion fell to 20 percent, while hay crops, small grains, and legumes all increased their share.47

In the sugar parishes, planters began using weedkillers for cultivating and mechanical cane cutters for harvesting, greatly reducing their labor requirements. Sugar grower Arthur Lemann of Ascension Parish remembered the sweeping changes that occurred on his family's plantation during the war. Machines eliminated the need for one hundred workers who were normally hired during the harvest season, and the fifty people who had formerly been employed to weed grass from the cane gave way to chemical herbicides and aerial spraying. During the 1944 harvest season, Louisiana growers used 356 mechanical harvesters that did the work of 21,000 people. Department of Agriculture officials reported that the harvesters helped to ease the labor situation and eliminated the necessity of paying wages that were higher than the minimum required to receive federal subsidies. The next year, Iberville Parish extension agent R. J. Badeaux confirmed the trend toward mechanization, citing it as the “natural road” for plantation owners concerned with efficiency and economy.48

These developments accelerated the displacement of farm families from the land that had begun during the New Deal era. As in the decade from 1930 to 1940, the number of tractors in Louisiana almost doubled again between 1940 and 1945, increasing from 9,476 to 17,630. Correspondingly, the number of farm operators declined from 150,007 to 129,295, a decrease of 14 percent. The number of black farmers dropped by a slightly higher rate, from 59,584 to 49,131 (18 percent). As long as the armed forces and war industries stood ready to absorb these workers, the consequences were not catastrophic for African Americans (although they caused severe problems for many communities in later decades). Those who moved from farm to factory increased their incomes and achieved levels of independence from white people that most plantation workers could not hope to enjoy. Meanwhile, larger crop acreages and better prices for farm products meant that conditions for tenant families who remained on the land also improved. Between 1940 and 1945 black farm operators in the state increased the average value of their lands and buildings by 38 percent, from $1,123 to $1,545. While tenancy declined, black farm ownership increased in the 1940s, reflecting the higher levels of prosperity that all farmers enjoyed during the war.49 (See Table 6.2.)

Table 6.2 African American Farm Operators in Louisiana, 1940–1960 | ||||||

| 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | ||||

| Tenure | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

| Owners | 11,187 | 19 | 12,965 | 32 | 8,666 | 49 |

| Managers | 17 | (-)a | 22 | (-) | 13 | (-) |

| Tenants | 48,380 | 81 | 27,669 | 68 | 9,064 | 51 |

| Total | 59,584 | 100 | 40,656 | 100 | 17,743 | 100 |

SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, United States Census of Agriculture: 1959, Volume 1: Counties, Part 35: Louisiana (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1961), 6. a(-) indicates less than 0.5 percent. | ||||||

As African Americans continued to gain economically, white Louisianans became increasingly alarmed. The sentiments expressed by many people revealed that their concerns stemmed from a much more complicated set of beliefs than the simple idea that black people were inferior. Some of the real fears underlying the commitment to white supremacy were voiced by a woman who complained about recent efforts to improve educational opportunities for African Americans, then stated, “I think they like to study; they're more ambitious than we are. . . . The government is giving ‘em too much education. Builds ‘em schools, colleges, and universities. They're supposed to be lower class than we are, aren't they? But they keep on educating them.”50 Government researchers investigating racial tensions in defense industries found white workers fearful that the war was “permanently destroying barriers against Negro competition” and likely to view the movement of African Americans into new occupations as a threat to their economic security.51 Southern business owners who relied on racism to keep wages low for both white and black labor were among those who were most concerned about threats to the social order. Out of the various groups that made up the OWI's nationwide pool of correspondents, business leaders were the least supportive of equality. Their proposed solution to the problem of racial animosity was invariably to “Keep the Negro in his place, and, as a corollary, see that segregation is rigidly enforced.”52 These reports suggest that at least some people who sought to deny African Americans access to education, skilled jobs, and political participation did so not because they believed that black people lacked the requisite abilities, but because they knew the opposite to be true.

White insecurity frequently manifested itself in violence. In February 1943 white guards and workers at the Delta Shipbuilding Company in New Orleans dragged a black truck driver from his vehicle and beat him severely after he blew his horn at a group of white people who were obstructing his path. A year later the sheriff and deputies of New Iberia accorded similar treatment to a group of NAACP leaders who had helped to establish a black welding school in the town. Some of the worst attacks were directed against black people in the armed forces. In January 1942 twelve African Americans were shot during a riot that occurred near Camp Claiborne, and in August 1944 a soldier reported that local white people seemed determined to spark a repeat performance of that event. He had heard rumors that three black servicemen had recently been found dead in the area and stated, “Now right at this moment the woods surrounding the camp are swarming with Louisiana hoogies armed with rifles and shot guns even the little kids have 22 cal. rifles and B & B guns filled with anxiety to shoot a Negro soldier.”53 In 1943 a mob seized a soldier from his hospital bed in Camp Polk and hanged him for allegedly insulting a white woman. A few months later, in Beauregard Parish, four white men stopped to offer a black soldier a ride to the bus station, and when he got into their car they branded him on the face with a hot iron. One particularly disturbing incident occurred in March 1944, when Private Edward Green boarded a bus in Alexandria and sat down in the section reserved for white people. The bus driver told him to move to the back, and when Green refused, the white man pointed a gun at him and ordered him to get off the bus. Although Green complied with this request, the driver shot and killed him anyway. Members of the local branch of the NAACP reported to the national office that Green was the fourth or fifth black soldier killed by white people in the area since the beginning of the war.54

In some parishes, white civilians and officials openly prepared for a “race war.” When Louisiana legislators authorized the formation of a state guard, the first places its chief officer decided to organize were areas “where there're lots of Negroes.” G. P. Bullis, who represented Concordia Parish in the state legislature, wrote to the commander in January 1943 to request urgent action in establishing a company of the guard in Ferriday. “We feel that we especially need this guard, because we live in a section which has some sparcely settled areas; also four-fifths of our population are negroes,” he explained. “This entire area is delta land, heavily populated with negroes, and a guard unit seems especially desirable here.” A few months later, the mayor of Ferriday wrote to express similar sentiments, saying, “The state as a whole is going to need [the Home Guard] very badly, and especially will the sections having large negro populations, of which this community is one, need it.” White people in several other parts of the state also believed violent uprisings by African Americans were imminent. “I think we're going to have race riots that are going to back everything else we've known off the board,” and “I think our next war will be coming with the colored folks” were two of the comments noted by Edgar Schuler in his “Weekly Tensions Report” during March and April 1943.55

White Louisianans’ fears were exaggerated but not completely unfounded. Between June 1942 and July 1943 their state was home to the “eighteen thousand bitter, frustrated, armed black men” who made up the U.S. Army's Ninety-third Division, the largest concentration of African American soldiers in the country. These troops were acutely aware of the lynchings, riots, and violent attacks on black people that were occurring throughout the nation, and they had experienced similar treatment themselves. During their stay in Louisiana Nelson Peery and a small group of other soldiers secretly obtained and stockpiled ammunition, intending to fight back against white violence. The men contemplated going to the assistance of African Americans in nearby Beaumont, Texas, when rioting broke out there in June 1943 but decided it was too risky. After intelligence agents in the War Department learned of the conspiracy, military commanders quickly decided to transfer the division out of the South. A few weeks after the Texas riots, the men of the Ninety-third left Louisiana bound for the isolated Mojave Desert in California.56

Based on reports that reached them from Louisiana and elsewhere, government researchers discerned the existence of a “growing and militant minority of Negroes” who were “increasingly talking of a resort to violent action to maintain their rights.” The federal government had done nothing to prevent violence against African Americans, leaving many to conclude that their only recourse was to defend themselves.57 The Baltimore Afro-American editorialized in 1944, “If the Army can't or won't protect soldiers in the Southern camps, has anybody objections to soldiers protecting themselves? . . . They practice with jiujitsu, knives, revolvers, machine guns, tanks and cannons, and then sit on a bus seat while a driver fills them full of lead.”58

In the minds of most black people, fighting back against white violence had never entailed much moral anguish or required justification. In the 1940s, the fact that Americans had taken up arms to fight a racist regime in Germany that closely resembled the racist regime in Louisiana provided an even more powerful rationale for using armed self-defense. John Henry Scott of East Carroll Parish explained, “I do not consider violence protecting yourself, no more than the soldiers out there where they fighting war. . . . Christ say put your sword down if you're fighting for his cause but when you going to fight for democracy why you pick your gun up. So if I could pick my gun up to go across the ocean to fight for democracy naturally I could pick my gun up to protect my democracy at home. And I wouldn't call that violence.”59

Other black Louisianans seem to have shared Scott's views. A young man who was attacked by a white soldier after refusing to give up his seat while waiting at a first-aid station shot his assailant in self-defense. In a letter to his mother, he declared: “I am not going to stand for any misstreatment. After all I didn't ask to come into the Army. And after I have been put here, I won't be treated like a dog.” He had told officers who suggested he ought to show white people more respect, “If we were good enough to fight their war for them we were entitled to a littel respect too.” In a similar incident, Private Oliver W. Harris Jr. of Tallulah was arrested for aggravated assault against a hardware store owner while on leave from the army shortly after the end of the war. An account given to the NAACP by his wife explained that Harris had ordered a piece of tubing from the store that he intended to use to wire their home so they could have electric lights installed. When he went to pick up the tubing, he found that it had been cut too long. The manager of the store, R. L. Betz, told him that he would have to pay for all of the tubing, and Harris argued with the man, saying that he did not think he should have to pay for all of it because the store had made the mistake. “Mr. Betz then became very angry and struck my husband,” Cora Mae Harris stated. “My husband then picked up a shovel and proceeded to go to work on Mr. Betz, in the meantime, V. R. Dace, white clerk rushed up and struck my husband with a pipe. My husband managed to take the pipe away from Mr. Dace and work on him.” The white men both received severe cuts in the head.60

Taking note of such incidents, government analysts, civil rights activists, and other observers warned that unless the federal government showed some willingness to eliminate racial discrimination and safeguard black people's citizenship rights, disaster could result. Early in the war a leader of the MOWM predicted, “We are slowly moving into one of the most bloody national race riots in history. If the administration doesn't give Negroes equal rights we are going to run into it sure as hell.”61 Throughout the conflict liberals in the Roosevelt administration repeatedly urged the president to take decisive action on civil rights, including better enforcement of Executive Order 8802, equal treatment in the armed forces, and the inclusion of African Americans in defense programs. Roosevelt heeded this advice to whatever extent seemed possible without unduly angering powerful southern Democrats in Congress. The result was a series of limited concessions designed to reassure black Americans while attempting to avoid interference with the South's cherished racial traditions.62

Roosevelt refused requests by civil rights groups to fully integrate the armed forces, but in March 1943 the army ended its practice of constructing separate facilities for white and black soldiers and issued directives prohibiting the designation of camp amenities by race. The following year, the president issued an executive order mandating the desegregation of all officers’ clubs, service clubs, and other social facilities at army posts, although he modified it with a clause allowing individual commanders to disregard the order if they believed that its peaceful implementation was not possible. None of these measures succeeded in eliminating discrimination against African Americans in the camps. In addition, neither the federal government nor the army exercised much control over white civilians in the South, and violent attacks on black servicemen and women continued through the end of the war. As a “disgusted Negro Trooper” noted when African Americans at Camp Claiborne were threatened by white mobs in 1944, “This camp isn't run by government regulations its controlled by the state of Louisiana and white civilians.”63

Though federal authorities had thus far failed to prevent violence against African Americans, there were indications that they were becoming more willing to intervene in this area. Since 1939 the Civil Liberties Unit within the Department of Justice had been working on developing ways of using the Constitution and other federal laws to better protect the civil rights of individuals. Through careful study of the legislation, prosecution of court cases, and development of legal precedents, its staff worked to strengthen the government's ability to bring southern lynch mobs and other offenders to justice. These efforts received further impetus when Roosevelt appointed Francis Biddle to the attorney general's office in August 1941. Biddle had expressed a commitment to upholding Americans’ civil liberties, and the appointment received strong support from black leaders. In February 1942 the attorney general took the unprecedented action of ordering a federal investigation into the murder of a black man by a crowd of white people in Missouri. Three years later the Justice Department's civil rights section brought charges against law enforcement officers in Georgia who had administered a fatal beating to a black prisoner in their custody. Neither action resulted in convictions, but they revealed a change in attitude on the part of officials in Washington that seemed an encouraging sign.64

By far the most significant development of the war years was the Supreme Court's decision to outlaw the system of white-only primary elections in the South. In states where the Democratic Party was assured victory in any contest with Republicans, the only time voters had the opportunity to participate meaningfully in the political process was during the primary elections for Democratic candidates. Party officials argued that theirs was a private organization entitled to restrict its membership to white people. The Court's opinion in Smith v. Allwright (1944) rejected that view, stating that political parties were public entities and could not discriminate against African Americans. The decision removed a major obstacle to black voting in the South and encouraged mass voter registration efforts by the NAACP and other civil rights groups after the war.65

National political developments continued to favor African Americans through the end of the decade. The emerging Cold War with the Soviet Union and the need to seem credible as leaders of the “free” world meant that national elites remained susceptible to pressure from black Americans to ensure justice and equality within the United States. On taking office after Roosevelt's death in April 1945, President Harry Truman worked to maintain black people's support for his administration by taking several actions on civil rights. In the first year of his administration he advocated establishing a permanent FEPC, ordered the Justice Department to investigate the murders of several black people by white supremacists in Georgia, and appointed a committee to study the problem of racism. In October 1947 the President's Committee on Civil Rights presented its report, To Secure These Rights, urging the government to take sweeping measures to eliminate racial discrimination. Truman spoke on the issue of civil rights before Congress in January 1948, endorsing many of the committee's recommendations for action. He later issued executive orders to establish a Fair Employment Board within the Civil Service Commission and to desegregate the armed forces.66

Truman's actions precipitated an open split within the Democratic Party between its northern liberal and southern reactionary wings. After a bitter struggle at the party's 1948 national convention over the adoption of a civil rights plank and the nomination of Truman as presidential candidate, dissenting southern “Dixiecrats” organized the States’ Rights Party to contest the coming elections. Their actions failed to prevent the reelection of the president, and Truman carried all the southern states except Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Alabama. An NAACP newsletter stated optimistically that the election results proved that most white Americans supported civil rights and were prepared to see black people treated fairly at last.67

Whether or not this assessment was accurate, in the late 1940s African Americans were better placed than ever before to engage in organized, sustained attacks on white supremacy. The ideological implications of the war, increased economic opportunity and prosperity, and the federal government's gradual shift toward accepting its responsibility to ensure justice for all Americans suggested that the post–World War II era would bring important developments in the freedom struggle. Both white and black analysts pointed to the gains African Americans had made and predicted far-reaching consequences. Quite simply, as one writer stated, the nation's black citizens were “not content to return to serfdom in the South, or to second-class social and economic status in the industrial North.”68 White Louisianans who viewed these developments with trepidation were right to be afraid. In the next two decades, many of their worst fears were realized.