Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen was a Nazi concentration camp established in July 1936. It was located north of Berlin, near Oranienburg. Administered by the SS, Sachsenhausen initially housed political prisoners and others deemed “dangerous” to the German government. Beginning in 1937 and continuing into 1945, the camp expanded dramatically and soon became home to a wide array of detainees, including Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, male homosexuals, individuals deemed “asocial,” and Roma. Between 1936 and 1945 some 200,000 detainees were either incarcerated at Sachsenhausen or transited through it. A few Soviet civilians were held there, and the camp became a major staging area for Soviet prisoners of war. By 1945 the number of Jewish prisoners at Sachsenhausen totaled about 11,000. In the period immediate following Kristallnacht in 1938, at least 6,000 German Jews were rounded up and imprisoned at Sachesenhausen. Most Jews were released, however, and by early 1939 only 1,345 remained.

After World War II began in September 1939, however, Sachsenhausen once again became home to many Jews, mainly resident aliens who had been residing in Germany, or Polish Jews. Many of those people were transferred to death camps in the east, where most perished. In 1944 Hungarian and Polish Jews who had been residing in various ghettos began arriving in large numbers, while Soviet POWs began arriving in the late summer of 1941; as many as 18,000 of these men were shot and killed there between 1941 and 1945. Their bodies were cremated in an on-site crematorium. In the autumn of 1944 German officials arrested thousands of Polish civilians, of whom approximately 6,000 were sent to Sachsenhausen. Most were non-Jews.

As in all concentration camps, conditions at Sachsenhausen were appalling. Food was scant and of poor quality, living quarters were overcrowded, sanitation facilities were crude at best, and medical care was essentially nonexistent. Many prisoners were ordered to perform forced labor in area factories, where some were worked to the point of exhaustion and death. Malnutrition and disease were perhaps the biggest killers. Including the Russian POWs who died at Sachsenhausen, a total of some 30,000 people died at the camp between 1936 and 1945. Others were beaten to death or executed, and some became the victims of Nazi medical experimentation.

In early April 1945, as Allied troops closed in on Berlin, the SS decided to liquidate the facility. Prisoners were force marched toward the north and east, a brutal process that resulted in many more deaths. When the Soviet Army liberated Sachsenhausen on April 22, 1945, there were still some 3,000 prisoners there, including 1,400 women.

PAUL G. PIERPAOLI JR.

See also: Asocials; Concentration Camps; Fackenheim, Emil; Haas, Leo; Hoess, Rudolf; Homosexuals; Jehovah’s Witnesses; Medical Experimentation; Roma and Sinti; Salomon, Charlotte; Zyklon-B Case, 1946

Further Reading

Bartrop, Paul R. Surviving the Camps: Unity in Adversity during the Holocaust. Lanham (MD): University Press of America, 2000.

Sachsenhausen was a Nazi concentration camp near Berlin that housed political prisoners from its establishment in 1936 until its liberation in May 1945. During its existence some 30,000 prisoners lost their lives there from a wide variety of causes. Toward the end of the war, with the advance of the Soviets, Sachsenhausen was evacuated. A death march took place in April 1945, during which thousands did not survive. On April 22, 1945, the camp’s remaining 3,000 inmates, including 1,400 women, were liberated by the Soviet and Polish troops. (AP Photo)

Kogon, Eugen. The Theory and Practice of Hell: The German Concentration Camps and the System behind Them. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

__________________

Salaspils

Salaspils is a small city in Latvia, situated on the Daugava River. It is located about 11 miles (18 kilometers) to the southeast of Latvia’s capital, Riga.

Toward the end of 1941 a concentration camp, a little over one mile out of town, was established at Salaspils. Originally it was intended for former Soviet prisoners of war and political prisoners, but by the time it was at its peak the camp became the largest civilian concentration camp in any of the Baltic republics. Officially, Salaspils (known in German as Kurtenhof) was designated as a Police Prison and Work Education Camp (Polizeigegfängnis und Arbeitserziehungslager), spread over an area measuring about 650 by 450 yards.

In October 1941 a senior Einsatzgruppen officer, SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Lange, began planning a detention camp to be built at Salaspils. He then oversaw the planning and implementation of the Rumbula massacre, a program that saw the murder of 24,000 Latvian Jews from the Riga ghetto, which occurred between November 30 and December 8, 1941. Later in December he began working as commander of both the security police (Sicherheitspolizei) in Latvia and also of the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst). His idea for the Salaspils camp was to create a place in which to confine not only those arrested in Latvia for political reasons or as resisters but also as an end point for Jews deported from Germany. Eventually, this would also extend to other occupied countries.

There was a precedent for this dating to before the establishment of Salaspils. On November 29, 1941, a trainload of approximately one thousand Jews from Germany arrived in Riga, where they were murdered. This served as a precedent for others, starting on December 3, 1941. Salaspils now became a convenient location for the Nazis’ grisly task, situated on the main rail line between Riga and the next largest city in Latvia, Daugavpils.

Development of the camp took place during January 1942, when around one thousand Jews from the Riga ghetto were conscripted to work on the site. By the fall of 1942 Salaspils was comprised of 15 barracks. In addition, there were two additional camps for Soviet prisoners of war nearby, which also fell under the overall jurisdiction of the camp administration. The death rate here, as in other compounds holding Soviet POWs, was high; while the exact number is unclear and subject to varying estimates, perhaps up to a thousand Soviet prisoners died, the victims of inferior accommodation and sanitary conditions and poor nutrition.

There was a juvenile barrack block at Salaspils, where children aged from 7 to 10 years old, upon being separated from their parents, were held. It has been recorded that these children were often victims of medical experimentation, which, together with typhoid fever, measles, and other diseases, saw a death rate that numbered at least half of the children incarcerated. Indeed, in one of the burial places discovered after the war, 632 corpses of children of ages 5 to 9 were found. While imprisoned, moreover, children were given special badges with their names and family information on them, but should the badges be lost—which happened particularly with younger children, who would often play with their badges or swap them around—their identities would also be lost.

On January 20, 1942, in recognition of his anti-Jewish measures in Riga, Rudolf Lange was invited to attend the Wannsee Conference in Berlin. This only served to encourage him (as well as those around him) to push for higher results in the mass killing of Jews. Plans for the camp at Salaspils were then revised, with a projected population of 15,000 Jews deported from Germany anticipated. While this did not eventuate, nonetheless between 12,000 and 15,000 people did transit through the camp in one way or another during its existence.

Figures concerning the overall mortality rate at Salaspils have fluctuated considerably over time. A reasonable estimate for the total number of deaths has landed at anywhere between 2,000 and 3,000. Not all were Jews, though it is certain that hundreds of German Jews were deliberately murdered or died as a result of sickness, overwork as slave labor, or callous treatment on the part of the guards. During the Cold War, Soviet estimates placed the number of deaths at anywhere between 50,000 and 100,000, but these figures are clearly way too high on account of the camp never taking in that many prisoners to begin with.

On October 13, 1944, the Soviet army liberated Riga—now completely emptied of all of its Jewish population—and on the same day the camp at Salaspils was also overrun. On October 31, 1967, a memorial complex was opened at the site of the Salaspils concentration camp, embracing a small museum and various forms of commemorative artwork.

MICHAEL DICKERMAN

See also: Concentration Camps; Lange, Rudolf; Latvia; Riga; Rumbula Massacre

Further Reading

Buttar, Prit. Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II. Oxford: Osprey, 2013.

Ezergailis, Andrew. The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941–1944: The Missing Center. Riga: Historical Institute of Latvia, 1996.

__________________

Salkaházi, Sára

Sára Salkaházi was a Hungarian Catholic nun who saved the lives of approximately one hundred Jews during the Holocaust. She was born Sára Schalkház in Kassa (Košice) in the Slovak-speaking area of the Habsburg Empire on May 11, 1899. The second of three children, her father died when she was still an infant. A thoughtful and religiously devout child, as a teenager she began to write plays and short stories. As a young adult she earned an elementary school teacher’s degree, which was the highest available qualification for women in education at the time. She taught school only for one year, leaving to move to another profession, that of book-binding. Later still, she learned millinery. After this, she turned to journalism.

Politically, she joined the Christian Socialist Party of Czechoslovakia and worked as editor of the party newspaper with a specific focus on social problems as they pertained especially to women. Over time, however, she realized that something was missing, until she found solace in religion.

Only after a long personal journey did she decide that her life should be spent in the service of others. In 1929 she entered the Society of the Sisters of Social Service in Budapest, a religious order founded in 1923 by Margit Slachta devoted to charitable, social, and women’s causes. At Pentecost 1930 she took her first vows, choosing as her personal motto the words “Here am I! Send me!” (Isaiah 6:8). She took her final vows in 1940.

In 1941 Sister Sára, as she was now known, was sent to Budapest to serve as the national director of the Hungarian Catholic Working Women’s Movement. She became editor of the movement’s publications and through these cautioned members against the growing influence of Nazism. She also established a network of Working Girls’ Homes in order to create a safe environment for working single women.

With the onset of war, political conditions in Budapest became less clear-cut than they were in earlier times. The Arrow Cross Party, the Nazi-inspired antisemitic movement in Hungary, began persecuting Jews, and the Sisters of Social Service, in response, commenced a program of providing safe havens for Jews fleeing from harassment. Sister Sára opened up the order’s Working Girls’ Homes as places of refuge under increasingly dangerous circumstances with other efforts extended to the provision of food and other vital goods.

As conditions worsened, by 1943 she saw there was only one possible option for her to consider; in order to truly live up to the example set by Jesus, she offered her life for the Society of the Sisters of Social Service and its mission. She pledged herself to God as a willing sacrifice to ensure that the other sisters and the order were not harmed.

With the intensification of anti-Jewish persecution during 1944, Sister Sára redoubled her efforts to save as many people as she could. Ultimately, the Society sheltered up to a thousand Jews, with Sister Sára personally responsible for approximately one hundred.

On the morning of December 27, 1944, armed Arrow Cross troops came to one of the Girls’ Homes under Sister Sára’s care, looking for Jews. They took four Jewish women and children and a religion teacher, Vilma Bernovits, into custody. Sister Sára was not present at that time, but when she arrived she was immediately detained. Later that night the little group was driven to the Danube Embankment, stripped naked, and shot into the river. It was said that as they were lined up Sister Sára knelt and made the sign of the cross. Her body was never recovered.

In 1969, after having been nominated by the daughter of one of the Jewish women who was killed alongside her, Sister Sára was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous among the Nations. Further recognizing her martyrdom, on September 17, 2006, Sister Sára was beatified in a proclamation by Pope Benedict XVI, in what was the first beatification to take place in Hungary since that of King Stephen in 1083.

In an ongoing tribute to her martyrdom, the Sisters of Social Service now hold an annual candlelight memorial service on the Danube Embankment every December 27, the anniversary of Sister Sára’s death. It is generally acknowledged that offering herself as a martyr for the society saved not only many Jews suffering persecution but also the order itself.

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Arrow Cross; Catholic Church; Hungary; Rescuers of Jews; Righteous among the Nations; Slachta, Margit

Further Reading

Reeves, T. Zane. Shoes along the Danube: Based on a True Story. Durham (CT): Strategic Book Group, 2011.

Sisters of Social Service. Blessed Sára Salkaházi, Sister of Social Service, at http://www.salkahazisara.com/sss_en.html.

Yad Vashem. Sara Salkahazi, at http://db.yadvashem.org/righteous/family.html?language=en&itemId=4017359.

__________________

Salomon, Charlotte

Charlotte Salomon was a German Jewish artist whose autobiographical work, Life? or Theatre?, combines paintings, text, and musical cues in a unique chronicle of her life. Salomon’s autobiography deals with her childhood in Weimar-era Germany, her coming of age during the Nazi years, and her exile in France as a refugee from the Nazi regime. It reveals her battle to define her existence and identity in the face of constant personal and political conflict.

Born into a prosperous family in Berlin in 1917, the young Charlotte Salomon struggled to find her own place and voice amid the turbulence of interwar Germany and the antisemitic policies of the Nazi regime. She quit school in 1933 but later applied and was admitted to the esteemed Berlin Art Academy. (Her openly avowed Jewish heritage would eventually lead to her dismissal from that institution.) There she learned classical, Nazi-sanctioned methods and techniques of realism, from which she broke almost completely in her own artistic work.

Increasing persecution at the hands of Adolf Hitler’s government ultimately convinced the Salomon family to leave their homeland. In the immediate aftermath of the anti-Jewish pogrom known as Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass) on November 9, 1938, Salomon’s father, Albert, along with thousands of other Jews, was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin. His family managed to secure his release, and from that point forward the family prepared to leave Germany. Charlotte Salomon left in January 1939 to join her grandparents, who had fled Nazi rule in 1933, on the French Riviera. A plan to reunite with her father and stepmother in exile never materialized; her parents ended up in Amsterdam, where they survived World War II and the Holocaust.

After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Salomon’s grandmother, distressed by the expansion of Hitler’s empire, tried to commit suicide (she made another, successful attempt the following year). It was only then that Salomon learned a family secret hidden from her since childhood: six people in her family, including Salomon’s mother, had taken their own lives. (Salomon had been told that her mother, who died when Salomon was eight years old, had succumbed to influenza.) Her grandmother’s death, the dislocations of war, and her increasing clashes with her grandfather—including an exchange in which he angrily suggested that Salomon kill herself—provided her with the determination to paint the story of her life to avoid falling victim to this fate and as a means of grappling with her family’s history. Salomon spent more than a year crafting her autobiography in 1941 and 1942, composing over 1,300 notebook-sized gouache paintings on which text was written directly or on attached overlays. From these, she selected more than 700 for inclusion in Life? or Theatre?

In June 1943 Salomon married Alexander Nagler, an Austrian Jewish refugee also living in southern France. Just three months after their marriage, they were arrested during intensified Nazi roundups of Jews along the Riviera. Before her apprehension, Salomon had given Life? or Theatre? to a friend, with whom it safely remained until the end of the war. After her arrest, Salomon was transported to Auschwitz, where she apparently was gassed soon after her arrival on October 10, 1943.

ADAM C. STANLEY

See also: Art and the Holocaust; Kristallnacht; Sachsenhausen

Further Reading

Felstiner, Mary Lowenthal. To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Salomon, Charlotte. Life? or Theatre? Edited by Judith C. E. Belinfante, Christine Fischer-Defoy, and Ad Petersen. Zwolle (Netherlands): Waanders, 1998.

__________________

Salonika

Due to the vibrancy of its Jewish culture the city of Salonika (Thessaloniki) was known for more than five hundred years as the “Jerusalem of the Balkans.” St. Paul makes an important, though negative, reference to the community in 1 Thessalonians 2:14–16 (ca. 50–52 CE) as thwarting his agenda of promoting his new religious understanding. There are even scholars who have contended that the origins of settlement may go as far back as the Babylonian Exile of the Jews from Judea (ca. 586 BCE). Equally significant, with the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, many fled to this city in such large numbers that the Jews already living there (Romaniote—Jewish communities with distinctive features who have lived in Greece and neighboring areas for more than 2,000 years) were absorbed, albeit, at times, somewhat reluctantly, into a new cultural ethos and set of specifically Sephardic (Spanish) religious practices.

Be that as it may, in April 1941 the Germans both conquered and occupied Greece and divided the spoils into three zones of occupation: German, Bulgarian, and Italian. (Jews in the latter two zones would fare quite differently from each other: the Bulgarians were quick to implement the Nazi policies of death and destruction, while the Italians tended to ignore or evade the more heinous Nazi antisemitic decrees and activities.) At war’s end, however, more than 95% of the 50,000 Jews initially found in Salonika under German control had been murdered, either directly in the city itself or transported to the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed immediately upon arrival. Others—males—would be become part of the internal camp labor force, especially Sonderkommando—“special handlers”—tasked with emptying out the gas chambers of bodies, examining them for hidden valuables, transporting them to the crematoria, and, finally, removing the increasingly large quantities of ashes. Many of these same Jewish Greeks (the preferred more accurate term) would also play a part in the unsuccessful Auschwitz uprising, which would destroy one of the crematoria. Several members of the Salonikan leadership, including Rabbi Koretz and his family, were transported to Bergen-Belsen.

From the initial Nazi takeover until February 1943, the Jewish community of Salonika would experience increasing pressure on its leadership with the arrests and removal of those in charge, especially Chief Rabbi Tzvi Koretz, a divisive figure who would be transported to and imprisoned in Vienna, Austria, only to later return and resume his position and that of president of the Jewish community. (Even today, Koretz remains something of a controversial figure among both survivors and historians, questioning not only his possible collaborationist activities but also his imperial high-handed leadership, his accomodationist subservience, and the like.)

With the arrival of Adolf Eichmann’s henchmen SS Hauptsturmführer Dieter Wisliceny and SS Hauptsturmführer Alois Brunner—the latter would go on to become the commandant of Drancy, France’s primary deportation camp, later dying in Damascus, Syria, where he fled after the war—and the active complicity of German SS Captain Max Merten; the German plenipotentiary Günther Altenburg; and the governor-general of Macedonia, Vasilis Simonides, the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” (Endlösung der Judenfrage) would begin to take an ominous turn.

On July 11, 1942, 9,000 Jewish men between the ages of 18 and 45 were told to assemble in the Plateia Eleftheria (Liberty Square) for forced labor registration. Without shade, water, or food, the Germans instituted a vigorous calisthenics regimen replete with beatings and verbal harassments from which many died in the sweltering heat of that month. Two thousand of the survivors would be transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and elsewhere to work for the German army. The remaining men were ransomed after a negotiation between the Nazis and the organized Jewish community of Greece to the tune of $3.5 billion drachmas (more than $1,000,000 USD). Four thousand would be put to work building a road linking Salonika with Katerini and Larissa through lice-infested territory. In addition, with the further collaboration of the Greek authorities, the huge Jewish cemetery of Salonika, housing more than 500,000 graves, was plundered of its tombstones to be used for construction projects. (Today, Aristotle University is built upon this site.)

By the end of February 1943 the remaining Jews of Salonika were rounded up and forced into three ghettos, the ultimate goal of which was to make their deportation to death that much easier. The ghettos were Kalamaria, Singrou, and Vardar/Agia Paraskevi. Ironically, the deportation camp location was in the Baron (Maurice/Moritz) de Hirsch section of the city, funded by the German philanthropist to care for the less fortunate, often refugees, and make their transition into city life that much easier, because of its proximity to the train station.

The deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau began on February 8, 1943, with the first of what would be 19 transports of more than 45,000 Jews from Salonika. The last transport left on August 8, 1943. By the end of the war, only two thousand Jews were left alive in Salonika.

Ironically, the tragic fate of the Jewish Greeks of Salonika was not unknown to the Allies, due to reports appearing in The Times, London (May, 1943) and the New York Times (February 1944, May 1944, and November 1944). Nothing, however, was done to increase their chances of survival.

STEVEN LEONARD JACOBS

See also: Auschwitz; Birkenau; Brunner, Alois; Collaboration; Greece; Sonderkommando; Venezia, Shlomo

Further Reading

Apostolou, Andrew. “‘The Exception of Salonika:’ Bystanders and Collaborators in Northern Greece.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 14, 2 (2000), 165–196.

Bowman, Steven B. Jewish Resistance in Wartime Greece. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2006.

Holst-Warhaft, Gail. “The Tragedy of Greek Jews: Three Survivors’ Accounts.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 13, 1 (1999), 98–108.

Matsas, Michael. The Illusion of Safety: The Story of the Greek Jews during the Second World War. New York: Pella, 1997.

Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Mazower, Mark. Salonica: City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims, and Jews, 1430–1950. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

__________________

Sauckel, Fritz

Ernst Friedrich Christoph “Fritz” Sauckel was a member of the German Nazi Party and the general plenipotentiary for labor deployment from 1942 to the end of World War II. He was one of 24 Nazis to be accused, tried, and convicted of war crimes during the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–1946. As general plenipotentiary for labor deployment, Sauckel was responsible for providing the forced labor to accommodate wartime productivity in Nazi Germany. Due to his efforts, approximately 5 million people were deported from their homes throughout the Third Reich and forced to work for the German war machine.

Sauckel was born on October 27, 1894, in Bavaria. The only son of a postman and a seamstress, he spent his pre–World War I years working with the merchant marine in Norway and Sweden. As a sailor, he rose to the rank of Vollmatrose, or able-bodied seaman. At the start of World War I he was working on a German vessel headed for Australia when it was captured by the British and its crew interned. He spent four years as a captive in France, from August 1914 to November 1919.

Sauckel returned to Germany after the war, joining the German Nazi Party in 1921. Six years later, in 1927, he was appointed Gauleiter (a Nazi district political governer) of Thuringia, a central-eastern region of Germany. Sauckel served as a member of Thuringian government into the 1930s, and following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933 he was promoted to Reich regent of Thuringia and Reichstag member and an Obergruppenführer in the SS and SA.

In 1942 Sauckel was again promoted, to general plenipotentiary for labor deployment, after a recommendation from Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler’s private secretary. In this capacity, Sauckel was directly subordinate to Hermann Göring, president of the Reichstag. The war effort resulted in increasing demands for labor in Germany. Unfortunately, voluntary labor within the Reich was severely lacking, and Sauckel turned to Germany’s newly occupied territories, particularly Poland and the Soviet Union. According to Sauckel’s testimony at Nuremberg, of the 5 million people who were placed in forced labor, approximately 200,000 came voluntarily. Saukel’s view was that all workers were to be exploited in the most efficient way possible: “All the men must be fed, sheltered and treated in such a way as to exploit them to the highest possible extent at the lowest conceivable degree of expenditure.” Such management led to the death of thousands of Jews in the work camps in Poland and other eastern territories.

In 1945, following the end of World War II, Sauckel and 23 other Nazi officials were tried for various counts of war crimes. The Nuremberg Trials, which took place from November 20, 1945, to October 1, 1946, were a series of Allied military tribunals to bring the biggest Nazi criminals to justice. Sauckel swore in his testimony that he was innocent of all war crimes and that he had been unaware of the concentration camps. He defended his position as Reich plenipotentiary for labor, stating his job had “nothing to do with exploitation. It is an economic process for supplying labor.” He was found not guilty on Nuremberg Trials’ indictments one and two, namely “The Common Plan or Conspiracy” and “Crimes against Peace.” However, he was found guilty on indictments three and four, “War Crimes” and “Crimes against Humanity” for his work as general plenipotentiary for labor deployment. He was sentenced to death by hanging and was executed on October 16, 1946. His last words on the scaffold were recorded as, “Ich sterbe unschuldig, mein Urteil ist ungerecht. Gott beschütze Deutschland!” or, “I die an innocent man, my sentence is unjust. God protect Germany!”

DANIELLE JEAN DREW

See also: Bormann, Martin; Crimes against Humanity; Göring, Hermann; National Socialist German Workers’ Party; Nuremberg Trials; Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup; War Crimes

Further Reading

Buggeln, Marc. Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Plato, Alexander Von, Almut Leh, and Christoph Thonfeld. Hitler’s Slaves: Life Stories of Forced Labourers in Nazi-Occupied Europe. New York: Berghahn Books, 2010.

Roland, Paul. The Nuremberg Trials: The Nazis and Their Crimes against Humanity. New York: Chartwell Books, 2010.

__________________

Schacter, Herschel

Herschel Schacter was an influential Orthodox rabbi who was the first Jewish chaplain in the U.S. Army to enter the Buchenwald concentration camp upon its liberation in April 1945.

Schacter was born on October 10, 1917, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of immigrants from Poland. After receiving a BA degree from New York’s Yeshiva University in 1938, he was ordained a rabbi in 1941, having studied under the highly esteemed Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. During 1941 and part of 1942, Schacter served as a rabbi in Stamford, Connecticut, before enlisting in the U.S. Army as a chaplain in 1942. He held the rank of lieutenant. Throughout World War II, he served in a variety of locations and settings in the European theater.

On April 11, 1945, advance units of the U.S. Third Army (VIII Corps) made their way to Buchenwald. Having learned that the concentration camp was about to be liberated, Schacter commandeered a jeep and raced to the camp. What he saw when he arrived was horrifying and heartbreaking. Emaciated, ill prisoners lay in squalid barracks, while piles of corpses were strewn about like firewood. He then proceeded to go from barracks to barracks, shouting in Yiddish, “Peace be upon you Jews, you are Free!”

Schacter later described a deeply moving scene. As he moved around the camp, he spotted a seven-year-old boy cowering in a dark corner. He picked the boy up and, asking him his name, the child meekly replied, “Lulek.” Schacter then asked him how old he was. The boy replied, “What difference does it make? I’m older than you anyway.” Puzzled, the chaplain asked him what he meant. The boy proceeded to tell him “because you cry and laugh like a child…. I haven’t laughed in a long time, and I don’t cry anymore. So who’s older?” The young boy would later migrate to Palestine and become a rabbi. Now known as Yisrael Meir Lau, he serves as Tel Aviv’s chief rabbi.

After Buchenwald’s liberation, Schacter remained there for many months. He ministered to the survivors, held religious ceremonies, and later helped to resettle them. There had been almost 1,000 orphans at Buchenwald, nearly all of whom Schacter helped resettle. Many went to France, including a young Elie Wiesel, who later became a renowned writer, while others went to Switzerland. Schacter himself accompanied a group of orphans to Palestine. He was discharged from the army in early 1946.

In 1947 Rabbi Schacter became the chief rabbi for the Mosholu Jewish Center in the Bronx, New York, where he remained until 1999, when the facility was closed. Schacter died in the Bronx on March 21, 2013. In 2011 Rabbi Lau published a memoir, Out of the Depths, which details his encounter with Schacter in 1945 and how it affected the remainder of his life.

PAUL G. PIERPAOLI JR.

See also: Buchenwald; Liberation, Concentration Camps; Wiesel, Elie

Further Reading

Lau, Rabbi Israel Meir. Out of the Depths: The Story of a Child of Buchenwald Who Returned Home at Last. New York: Sterling, 2011.

__________________

Schindler, Oskar

Oskar Schindler is perhaps the best known rescuer of Jews during the Holocaust by virtue of a multi-award-winning movie, Schindler’s List, made by filmmaker Steven Spielberg in 1993. At his enamelware and munitions factories in Poland and later Bohemia-Moravia, Schindler saved more than 1,200 Jews from extermination at the hands of the Nazis.

Born to Johann and Franziska Schindler, née Luser, on April 28, 1908, in Zwittau (Svitavy), Austria-Hungary, Oskar Schindler had an unsettled education that carried over to his early adult years. On March 6, 1928, he married Emilie Pelzl. An opportunist and womanizer always interested in get-rich-quick schemes that inevitably failed, with little else going for him he joined the Abwehr, the German military intelligence network, in 1936. He applied for membership in the Nazi Party on November 1, 1938, and in February 1939, five months after the German annexation of the Sudetenland, this was accepted.

Following the German invasion and occupation of Poland, Schindler moved to Kraków in October 1939. Taking advantage of the German occupation program to “Aryanize” businesses in the so-called Generalgouvernement (General Government), in November 1939 he purchased an enamelware factory from its Jewish owner, Nathan Wurzel, and reopened it as Deutsche Emalwarenfabrik (German Enamelware Factory), or, by its shortened version, Emalia. He employed Jewish slave labor, at extremely exploitative rates payable to the SS, which he brought in from the Kraków ghetto. After the ghetto’s liquidation in March 1943 the Jewish workforce was relocated to the concentration camp at Plaszów under the command of Amon Goeth.

Oskar Schindler was a German industrialist and rescuer of Jews credited with saving the lives of 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust. His first enamelware factory was located in Krakow, Poland, where he manufactured goods for the German military. This enabled his workers to be protected from deportation to the Nazi concentration camps. In 1963 he was recognized as one of the Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem. The photo shows Schindler with the original list of the 1,200 Jewish concentration camp prisoners whom he employed in his factory. (AP Photo/Michael Latz)

Schindler went to great lengths to ensure the survival of “his” Jews, or Schindlerjuden, as they came to be called. Though they were still subject to the draconian and deadly rules and regulations of the concentration camp (and the whims of Goeth’s erratic regime), Schindler made constant intercessions on the Jews’ behalf, seeing to it that they were neither deported nor killed. He repeatedly demanded that they not be harmed on the ground that they were essential to the war effort, and, with the assistance of his Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern, he managed to keep the prisoners in one place while making it appear as though the factory was performing valuable war work.

It was no surprise at first that Schindler was only interested in making money from his enterprise, but as he witnessed the brutal treatment Jews were experiencing, he became more and more disillusioned with Nazi ideology and what he saw it as representing. Over time he became transformed from the money-grubbing opportunist he had always been to a humanitarian with a desperate desire to save Jewish lives. The underlying reason for this change of heart has eluded historians, but it can be said with certainty that Schindler was never part of any organized resistance movement or rescue organization, and acted from motives that were his alone.

Protecting his workers came at a huge financial cost, but the money Schindler had made as a war profiteer he spent in bribes and expensive presents to Nazi officials. Eventually, he lost count of how much he had spent in protecting “his” Jews. Certainly, it was many millions of Reichsmarks. In trying to ensure that his workers would survive the war, he was prepared to spend all his money. Servicing huge costs in order to protect his workers, Schindler had to engage in illegal business dealings on the black market, which saw him arrested on three separate occasions. He was also twice arrested for Rassenschande, or “race shame,” after kissing Jewish girls—one of them on the cheek as a gesture of affection and gratitude.

With the advance of the Eastern Front during 1944, many of the concentration camps located in eastern Poland began to be closed down. Seeing the prospect of this happening to Plaszów, a Jew working as Goeth’s personal secretary, Mietek Pemper, informed Schindler that all factories not directly involved in the war effort, including his factory camp, were at risk. He then proposed that Schindler would be more secure if he were seen to be producing armaments instead of pots and pans. Accordingly, in October 1944, Schindler sought permission to relocate his factory to Brünnlitz (Brneˇnec) in Moravia, taking as many of his “highly skilled workers” as possible with him, and to resurrect it as an arms factory. Permission was granted, and the factory became reestablished as a subcamp of Gross-Rosen.

Pemper then compiled a list of people who, it was argued, had to go to Brünnlitz. The names were provided by a corrupt member of the Kraków Jewish police, Marcel Goldberg, who identified a thousand of Schindler’s workers and two hundred from the textile factory of a Viennese businessman in Kraków, Julius Madritsch. The lists were typed up by Goldberg; unlike popular wisdom, Schindler was not present when this took place. Nonetheless, all were sent to Brünnlitz: 800 men deported by the SS from Plaszów via Gross-Rosen and just over 300 women who went from Plaszów via Auschwitz, rescued at the last moment from gassing by the timely arrival of Schindler’s secretary, Hilde Albrecht, who came armed with bribes of black market goods, food, and diamonds.

Because they were relatively safe at Brünnlitz when compared to the possible fate that would have greeted the Jews if they had remained at Plaszów, Schindler worked at ensuring his charges would remain secure by continuing to bribe the SS and other Nazis, some of whom had an eye for profit, others with an ideological commitment that said the Jews had to keep working unto death.

By the time Brünnlitz was liberated by the Russians on May 9, 1945, Schindler was bankrupt and, as a member of the Nazi Party and a perceived war profiteer and exploiter of slave labor, he was on the run. He smuggled himself and his wife, Emilie, back into Germany, where they settled in Regensburg and kept a low profile.

They stayed there until 1949, when they migrated to Argentina. Just as before the war, he again failed in his business ventures. His marriage to Emilie broke down, and in 1957 they separated. In 1958 he returned to Germany alone.

On July 18, 1967, for his efforts in rescuing over 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust, Schindler was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous among the Nations. Emilie was similarly recognized on June 24, 1993. Oskar Schindler died, penniless, on October 9, 1974, in Hildesheim, Germany. Later, he was buried in Jerusalem on Mount Zion. He was the only member of the Nazi Party ever to be so honored.

In 1980 Australian novelist Thomas Keneally learned about Schindler from Leopold (Poldek) Pfefferberg, a “Schindler Jew.” The result was a fictionalized account of the story, Schindler’s Ark, which appeared in 1982. In the United States the book was published as Schindler’s List. The book was later adapted for the screen by Steven Spielberg, using the American title, to immense critical and popular acclaim. The film won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and Liam Neeson was nominated as Best Actor for his portrayal of Schindler. Because of the high profile accorded Schindler as a result of the movie, and a vast array of books and documentaries that followed, his name has become a byword for rescue during the Holocaust—such that one of the highest accolades many can today give a rescuer is that he or she is “the Oskar Schindler of …” a given situation.

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Aryanization; Generalgouvernement; Kraków-Plaszów; Rescuers of Jews; Righteous among the Nations; Schindler’s Jews; Schindler’s List

Further Reading

Crowe, David. Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activites, and the True Story Behind the List. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Keneally, Thomas. Schindler’s Ark. New York: Folio Society, 2009.

__________________

Schindler’s Jews

“Schindler’s Jews,” or Schindlerjuden in German, is a term that refers to a group of some 1,100 mostly Polish Jews who were saved from almost certain death during the Holocaust by German businessman Oskar Schindler. After the German invasion of Poland began on September 1, 1939, Schindler purchased an enamelware factory near Kraków, Poland. His accountant, a German-speaking Jew by the name of Itzhak Stern, helped Schindler secure the services of some 1,100 Polish Jews, who would work in his factory.

Schindler witnessed more and more brutality toward Jews in Kraków, which troubled him greatly. After Nazi soldiers rounded up scores of Jews in 1943 for deportation to concentration camps, Schindler stepped up his efforts to shield his Jewish workers from Nazi atrocities. Increasingly, Schindler defended his workforce and claimed exemptions for them because his business was considered essential to the war effort. Schindler treated his workers fairly and civilly, even permitting them to pray.

Late in the war, as Soviet troops advanced to the west, Schindler learned that Nazi officials planned to close all factories in Poland, including his own. He then convinced SS officials to allow him to operate a factory in Brünnlitz (now in the Czech Republic), where he would manufacture military items. He also received approval to relocate his mostly Jewish labor force to the new facility, under the premise that the workers were already trained and hence indispensable to his operations. Before the move, which took place in October 1944, a list of 1,200 workers—mostly Jews—was drawn up and presented to the authorities.

In reality, few military items were made in the new factory, and those that were had been purposely sabotaged. By mid-1945 Schindler and his family had closed the facility and fled to Austria, but almost all of his workers survived the war.

There are now more than 7,000 descendants of Schindler’s Jews living throughout the world, chiefly in Europe, Israel, and the United States. Nearly all of the original survivors have now died, and in January 2013, Leon Leyson, the youngest of the Schindler survivors, died at the age of 83 in Los Angeles, his adopted city. Leyson was reunited with Schindler almost 30 years after the war when Schindler visited the United States. Although there has been no formal mass reunion of Schindler’s Jews, a number of them did meet with other survivors after the war, often in conjunction with meetings with Schindler, who died in 1974.

Schindler’s deeds were later brought to light in a book written by Australian writer Thomas Keneally; titled Schindler’s Ark (1982), it was published as Schindler’s List in the United States. In 1993 Steven Spielberg produced a masterful and popular film rendition of the book, again titled Schindler’s List.

PAUL G. PIERPAOLI JR.

See also: Kraków-Plaszów; Schindler, Oskar; Schindler’s List

Further Reading

Crowe, David. Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activites, and the True Story Behind the List. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Keneally, Thomas. Schindler’s List. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

__________________

Schindler’s List

Considered perhaps the most famous Holocaust film ever to be made, Schindler’s List is a motion picture directed by multi-award-winning filmmaker Steven Spielberg in 1993. The film was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won seven: best picture, best director (Spielberg), best adapted screenplay (Steven Zaillian), best cinematography (Janusz Kaminski), best original score (John Williams), best editing (Michael Kahn), and best art direction (Ewa Tarnowska and Allan Starski).

The film was produced almost entirely in black and white, at times taking on the manner of a quasi-documentary, though color was introduced briefly on three occasions: in its opening and closing sequences, and showing a little girl in a red coat (the coat makes a brief appearance on one other occasion).

The movie starred Liam Neeson in the title role as Oskar Schindler, Ben Kingsley (Itzhak Stern), and Ralph Fiennes (Amon Goeth), and was based on Schindler’s Ark, a book from 1982 written by Australian writer Thomas Keneally. It tells the dramatic story of real-life Sudeten-German businessman and Nazi Oskar Schindler, a morally corrupt adulterer, opportunist, and profiteer, who operated a slave labor factory producing enamelware intended for military use in Kraków, Poland, during World War II.

The movie is a dramatized account of the life of Schindler during the Holocaust, as he makes a dramatic turnaround from exploiting Jewish slave labor to seeing the need to save the lives of his workers. Once he realizes a way to do so, he composes a list of those he wishes to save; a list that he strove to make as long as possible (eventually comprising nearly 1,200 names), right under the gaze of the SS.

Spielberg was said to have been interested in the story of Oskar Schindler from the time of the book’s first appearance but needed time to carefully consider how it could be made. He was, however, seemingly always determined to make the film, not only from an artistic perspective but also from the perspective of his own personal commitment; upon finishing, he later spoke of how the process of making of the movie had a deep emotional impact on him.

The three-hour-long epic has been hailed as among the most accurate portrayals of the reality of the Holocaust for the events it describes. In certain circles it stimulated controversy, however, particularly for its ending. After the audience has accompanied Schindler and those around him through their various ordeals and journeys, the film moves to a cemetery in Jerusalem, where surviving “Schindler Jews” (Schindlerjuden), accompanied by the actors who portrayed them in the movie, line up in order to place stones on Oskar Schindler’s grave—a traditional Jewish custom to signify that a visit has been made by one who remembers the departed. The last person at the grave is Liam Neeson (Oskar Schindler). He places a rose on the tombstone. A postscript informs viewers that the Jews saved by Schindler have now embraced life, with more than 6,000 descendants.

The reason for the controversy, among some critics, was because this was seen as both a maudlin and an inferior ending to what had otherwise been a brilliant evocation of the Holocaust experience—for some, it was even unnecessary. Despite this, the film generated additional historical research (particularly among younger viewers and schoolteachers), inspired new Jewish-Christian dialogue, and served to relocate the Holocaust at the forefront of American consciousness.

The movie’s tagline, coming from the Talmud (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5; Yerushalmi Talmud 4:9, Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 37a), is celebrated as an inscription inside a ring presented by the survivors to Schindler at the end of the movie: “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” As a coda for the whole movie, it was clear that Spielberg was attempting to send a moral message to his viewing audience through this device; indeed, through the whole movie. Building on this, in 1994 Spielberg founded and financed the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, whose aim was to record testimonies of survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust. In January 2006 it partnered with the University of California to establish the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education. The fundamental goal of the Shoah Foundation is to provide an oral history archive for the filmed testimony of as many survivors of the Holocaust as possible, so that future generations will be able to hear the actual voices of those who experienced the Holocaust in their very flesh.

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Schindler, Oskar; Schindler’s Jews

Further Reading

Fensch, Thomas. Oskar Schindler and His List: The Man, the Book, the Film, the Holocaust and Its Survivors. Forest Dale (VT): Paul S. Eriksson, 1995.

Loshitzky, Yosefa (Ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Palowski, Franciszek. The Making of Schindler’s List: Behind the Scenes of an Epic Film. New York: Birch Lane Press, 1998.

__________________

Schlegelberger, Franz

Louis Rudolph Franz Schlegelberger was state secretary in the German Reich Ministry of Justice and served as German justice minister during the Third Reich. He was the highest-ranking defendant at the Judges’ Trial in Nuremberg.

Schlegelberger was born on October 23, 1876, into a pious Protestant family from Königsberg, where he attended gymnasium and sat for his school-leaving examination in 1894. He began studying law in Königsberg in 1894, continuing his legal studies in Berlin from 1895 to 1896. In 1897 he passed the state legal examination. At the University of Königsberg (by some accounts, the University of Leipzig) he graduated as a doctor of law on December 1, 1899.

On December 9, 1901, Schlegelberger passed his state law examination. Two weeks later he became an assessor at the Königsberg local court, and on March 17, 1902, assistant judge at the Königsberg State Court. On September 16, 1904, he became a judge at the State Court in Lyck (now Ełk, Poland). In early May 1908 he went to the Berlin State Court and in the same year was appointed assistant judge at the Berlin Court of Appeals (Kammergericht). In 1914 he was appointed to the Kammergericht Council (Kammergerichtsrat) in Berlin, where he stayed until 1918.

On April 1, 1918, Schlegelberger became an associate at the Reich Justice Office, receiving appointment later in the year to the Secret Government Court and Executive Council. In 1927 he took on the post of ministerial director in the German Reich Ministry of Justice. Schlegelberger had been teaching in the Faculty of Law at the University of Berlin as an honorary professor since 1922 and was a well-known jurist who, in September 1929, even traveled to Latin America. On October 10, 1931, Schlegelberger was appointed state secretary at the Ministry of Justice under Franz Gürtner and kept this job until Gürtner’s death in 1941.

After the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, in an attempt to restrain executive power, Schlegelberger objected to a decree retroactively imposing the death penalty on those blamed for the Reichstag Fire on the basis that the decree was a violation of the ancient legal maxim nulla poena sine lege (“no punishment without law”). By January 30, 1938, following Adolf Hitler’s orders regarding judges in the Third Reich, Schlegelberger joined the Nazi Party.

In March 1940 Schlegelberger proposed that lawyers be expelled from their profession if they did not fully and without reservation support the National Socialist state. As minister of justice, he reiterated that call in a conference of German jurists and lawyers in April 1941. The first item on the conference agenda was the Nazi regime’s T-4 euthanasia initiative, in which Schlegelberger announced the Führer’s policies so that judges and public prosecutors understood that they might not use legal means to oppose the Aktion T-4 measures against the will of the Führer.

After Franz Gürtner’s death in 1941, Schlegelberger became provisional Reich minister of justice for the years 1941 and 1942 while still holding his post as state secretary. Otto Thierack was appointed after Schlegelberger’s acting position expired. During Schlegelberger’s period in office the number of judicial death sentences rose sharply. He drafted the Poland Penal Law Provision (Polenstrafrechtsverordnung), under which Poles were executed for tearing down German wall posters and proclamations.

Schlegelberger’s work assisted the institutionalization of torture in the Third Reich. After defendants accused of “political” crimes started to show signs of torture, Schlegelberger’s Justice Ministry “legalized” such acts, to such an extent that the Reich Ministry of Justice even established a “standard club” to be used in beatings, so that torture would at least be regularized.

In 1941 a police captain named Klinzmann was convicted of torture for beating an arson confession out of a Jewish farm laborer. When the German Supreme Court refused to hear Klinzmann’s appeal, Schlegelberger created a new procedure called “cancellation” that gave the Reich a means to end every trial independently of judicial decisions. Klinzmann was set free and so had no criminal record against his name.

On October 24, 1941, Schlegelberger wrote to the chief of the Reich Chancellery, Minister Hans Lammers, informing him that acting under the Führer Order of October 24, 1941, Schlegelberger had handed over to the Gestapo for execution a Jew named Markus Luftglass, sentenced by the Special Court (Sondergericht) in Katowice to two-and-a-half years in prison (for the crime of hoarding eggs). That was clearly a violation of the legal maxim “no punishment without law.”

In November 1941 Schlegelberger was among those whom Reinhard Heydrich invited to attend the Wannsee Conference. As things turned out, his subordinate, Roland Freisler, attended as Schlegelberger’s deputy. After the conference, Schlegelberger supported efforts to apply a more restrictive definition of the persons subjected to the “Final Solution.” In a letter on April 5, 1942, to Lammers, he suggested that “mixed people” should be given a choice between “evacuation to the East” or sterilization, writing that “The measures for the final solution of the Jewish question should extend only to full Jews and descendants of mixed marriages of the first degree, but should not apply to descendants of mixed marriages of the second degree…. There is no national interest in dissolving the marriage between such half-Jews and a full-blooded German.”

Schlegelberger wrote several books on the law and at the time of his retirement was called “the last of the German jurists.” Some of those law texts commenting upon German law were still in use and available for purchase in 2017. Upon Schegelberger’s retirement as justice minister on August 24, 1942, Hitler thanked him with a huge financial endowment and permitted him to purchase an estate with the money, something outside the rules then in force; clearly Hitler held Schlegelberger in high esteem.

After the war Schlegelberger was one of the main accused indicted in the Nuremberg Judges’ Trial in 1947. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for conspiracy to perpetrate war crimes and crimes against humanity. The judgment stated, in part, “that Schlegelberger supported the pretension of Hitler in his assumption of power to deal with life and death in disregard of even the pretense of judicial process. By his exhortations and directives, Schlegelberger contributed to the destruction of judicial independence. It was his signature on the decree of 7 February 1942 which imposed upon the Ministry of Justice and the courts the burden of the prosecution, trial, and disposal of the victims of Hitler’s Night and Fog. For this he must be charged with primary responsibility.”

In 1950 the 74-year-old Schlegelberger was released from prison on “health grounds” by the American High Commissioner for Germany. He then lived in Flensburg until his death at the old age of 93 on December 14, 1970.

Schlegelberger was perceived as a reluctant supporter of Hitler’s rule and given a lenient sentence. From the available records it appears that Schlegelberger’s most acute regrets dealt with what he experienced, rather than what he helped inflict on others. Given his record, he was the model for the character of Ernst Janning, the penitent German jurist portrayed by Burt Lancaster in the multi-award-winning motion picture Judgment at Nuremberg, a depiction of the Judges’ Trial at Nuremberg.

EVE E. GRIMM

See also: Crimes against Humanity; Euthanasia Program; Final Solution; Freisler, Roland; Judges’ Trial; Nacht und Nebel

Further Reading

Koch, H. W. In the Name of the Volk: Political Justice in Hitler’s Germany. London: I. B. Tauris, 1989.

Miller, Richard Lawrence. Nazi Justiz: Law of the Holocaust. Westport (CT): Praeger, 1995.

Muller, Ingo. Hitler’s Justice: The Courts of the Third Reich. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1991.

Nathans, Eli. “Legal Order as Motive and Mask: Franz Schlegelberger and the Nazi Administration of Justice.” Law and History Review 18, 2 (Summer 2000), 281–304.

__________________

Schmeling, Max

Max Schmeling was a German heavyweight boxer who risked his life to save two young Jewish brothers by hiding them in his hotel room and then helping them escape Germany during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938.

Of modest background, Maximilian Schmeling was born in Klein-Luckow, Germany, near Hamburg, on September 28, 1905. The son of a sailor, from a young age his life was to be that of a boxer. He turned professional in 1924 at age of 19 and won the German light heavyweight title two years later. On June 19, 1927, he won the European light heavyweight title, and then the German heavyweight crown. He soon went to the United States, where he had his first American fight at Madison Square Garden against Joe Monte on November 23, 1928. He won by knockout. The following year, also in New York, Schmeling signaled his intentions by defeating a pair of top heavyweights, Johnny Risko and Paulino Uzcudun.

With these victories, he moved to the number-two ranking and a shot at the heavyweight title. At that time the crown was vacant, and Schmeling met Jack Sharkey to settle the title. They met on June 12, 1930, and Schmeling won when Sharkey was disqualified in the fourth round after delivering a low blow. This became the only occasion in boxing history when the heavyweight championship was won by disqualification.

In April 1933, not long after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, he summoned Schmeling—by now his favorite athlete—for a private dinner meeting with himself, Hermann Göring, Josef Goebbels, and other Nazi officials. In discussion, he told Schmeling that when he was in the United States he should inform the American public that reports about Jewish persecution in Germany were untrue. When Schmeling arrived in New York he complied, saying that there was no antisemitism in Germany and emphasizing the point that his manager, Joe Jacobs, was Jewish. Few were convinced, particularly as Hitler had banned Jews from boxing soon after he and Schmeling had met.

In July 1933 Schmeling married a blond, beautiful Czech movie star, Anny Ondra, and the two became Germany’s most glamorous couple. The same year, Schmeling lost the title in a rematch with Sharkey after a controversial 15-round split decision, followed by defeat at the hands of Max Baer before a crowd of 60,000 at Yankee Stadium in June 1933. With this, the loss was deemed a “racial and cultural disgrace” by the Nazi propaganda newspaper Der Stürmer, which considered it outrageous that Schmeling would even have deigned to fight a “non-Aryan.” Baer’s father was Jewish, and Baer himself fought wearing shorts emblazoned with a Star of David.

By this stage Schmeling was viewed as a something of a Nazi puppet, when not being accused of sympathizing with Nazism. On March 10, 1935, he fought and knocked out American boxer Steve Hamas in Hamburg. At this, the 25,000 spectators spontaneously stood and sang the Horst Wessel (the Nazi anthem), with arms raised in the Hitler salute. This caused outrage in the United States, with Schmeling now being publicized in Germany as the very model of Aryan supremacy and Nazi racial superiority, something he would detest all his life.

During the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Schmeling requested from Hitler a promise that all American athletes would be protected, which Hitler respected. Around this time, the German dictator also began pressuring Schmeling to join the Nazi Party, which would have made a wonderful propaganda coup for the regime. Not only did Schmeling refuse, he also turned down every inducement to stop associating with German Jews or fire Joe Jacobs as his manager.

Nonetheless, the German propaganda machine still found enough traction in Schmeling to retain him as a propaganda model of Aryan supremacy. The U.S. public also wanted Schmeling, but for the opposite reason. Rather than celebrating him, many in the United States hoped he would come back for another fight and lose—this time against the young American hero, the “Brown Bomber,” Joe Louis. As Schmeling’s record of late had not been strong, he went into the fight a 10–1 underdog, and many people thought that at 30 years of age he was past his prime.

On June 19, 1936, the fight took place at Yankee Stadium. Schmeling had studied his opponent’s technique closely and found a weakness in his defense. In the 12th round, he scored what some consider the upset of the century, when he sensationally knocked Louis out. In Germany, the Nazi press—to Schmeling’s dismay—boasted of the victory as representing white Aryan supremacy. When he returned to Berlin, he was invited by Hitler to join him for lunch.

A rematch at Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1938, was arguably the most famous boxing bout in history. The fight had huge implications, plain for all to see. It became a cultural and political event, billed as a battle of the Aryan versus the Negro, a struggle of evil against good. Held before a crowd of more than 70,000, the match saw a determined and highly motivated Joe Louis knock Schmeling out within two minutes and four seconds of the first round.

Schmeling later said that although he was knocked out in the first round and shipped home on a stretcher with a severely damaged spine, he was relieved that the defeat took Nazi expectations off him. It made it easier for him to refuse to act as a Nazi, and he was shunned by Hitler and the Nazi hierarchy for having “shamed” the Aryan Superman ideal.

On the night of November 9, 1938, as antisemitic mobs were sacking Jewish property throughout the Reich, Schmeling’s opposition to Nazism was tested as never before. One of his friends, a Jew named David Lewin, was a tailor at Prince of Wales, the shop where Schmeling bought his suits. As the Kristallnacht intensified throughout the night, Lewin asked Schmeling to shelter his two sons, Heinz and Werner, aged 14 and 15 respectively. Without hesitation, Schmeling took them to his room in the downtown Excelsior Hotel and kept them there for three days. He told the desk clerk that he was ill and must not be disturbed. After things settled down, he drove them to his house for further hiding; waiting another two days, he then delivered them to their father.

In 1939 Schmeling helped the family to flee the country altogether. They went to the United States where one of them, Henri Lewin, became a prominent hotel owner in Las Vegas.

For his part, Hitler never forgave Schmeling for losing to Louis, especially given the circumstances, or for refusing to join the Nazi Party. During World War II he saw to it that at the age of 35 Schmeling would be drafted into the Luftwaffe as an elite paratrooper, where he served during the Battle of Crete in May 1941. It was said that the Führer took a personal interest in seeing to it that the former champion would be sent on suicide missions.

After the war, Schmeling tried to reinvigorate his boxing career. He fought five times, but in May 1948 was beaten by Walter Neusel, whom he had defeated in a classic match several years earlier. This was his last fight. Across his career, Schmeling’s record read as 70 fights for 56 wins (40 by KO) and four draws.

In retirement, Schmeling became one of Germany’s most revered and respected sports figures. He remained popular not only in Germany but also in America. He was awarded the Golden Ribbon of the German Sports Press Society and became an honorary citizen of the City of Los Angeles. In 1967 he published his autobiography, Ich Boxte mich durchs Leben, later published in English as Max Schmeling: An Autobiography.

He bought a Coca-Cola dealership in 1957, from which he derived much financial success. This enabled him to become one of Germany’s most beloved philanthropists, a popular and much respected figure not only in Germany but also in America. He became friends with many of his former boxing opponents, in particular Joe Louis. He would often help out Louis financially, and their friendship lasted until the American’s death in 1981, when Schmeling, in a final tribute, paid for the funeral.

On February 28, 1987, Schmeling’s wife of 54 years, Anny Ondra, died. In 1992 he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, though sadly he was never honored by Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile for his actions during the Kristallnacht of November 1938. No one, it seems, ever nominated him.

Max Schmeling was a man in conflict with both the Hitler regime and the racial policies of Nazism. The degree of resistance he showed was built around a sense of what it was to be a decent human being. On February 2, 2005, he died aged 99, at his home in Hollenstedt, near Hamburg.

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Der Stürmer; Kristallnacht; Propaganda; Rescuers of Jews

Hughes, Jon. “From Hitler’s Champion to German of the Century: On the Representation and Reinvention of Max Schmeling.” In Pól Ó Dochartaigh and Christiane Schönfeld (Eds.), Representing the “Good German” in Literature and Culture after 1945: Altruism and Moral Ambiguity. Rochester (NY): Camden House, 2013, 66–84.

Margolick, David. Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Myler, Patrick. Ring of Hate: The Brown Bomber and Hitler’s Hero: Joe Louis v Max Schmeling and the Bitter Propaganda War. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2005.

Schmeling, Max. Max Schmeling: An Autobiography. Lanham (MD): Taylor Trade, 1994.

__________________

Schmid, Anton

Anton Schmid, an Austrian soldier serving in the Wehrmacht during World War II, resisted the Holocaust through the saving of Jews—and was executed as a result. He was born in Vienna in 1900, married his wife Stefi, and had a daughter. An electrician by trade, by the time he reached early middle age he owned a radio shop and lived a comfortable life in Vienna.

Having been drafted into the German army after the Anschluss with Austria, he was mobilized upon the outbreak of war in September 1939. He was sent first to Poland, and then, after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, transferred to Nazi-occupied Lithuania. By the autumn of 1941 the now Sergeant Schmid was stationed near Vilna (Vilnius).

Witnessing the creation of the Vilna ghetto in September 1941, Schmid soon learned what the fate of the Jews was to be. Mass killings had already been taking place since July 1941, and they continued throughout the summer and fall. By the end of the year, some 21,700 Jews had been murdered by Einstatzgruppen units and their Lithuanian allies in the Ponary Forest near Vilna. Schmid was appalled, particularly as he saw children being beaten in front of him. From his perspective, it was unthinkable not to try to find a way to go to the Jews’ aid.

Schmid’s assignment in Vilna saw him commanding a unit responsible for reassigning soldiers who had been separated from their detachments. He was based at the Vilna train station; from here, he saw a great deal of the treatment meted out to Jews, and he lost no opportunity in using his position to ease their situation. He would take them off the trains and employ them as workers, arranged for some to be released from prison, organized new papers for others, and even—at immense personal risk—sheltered Jews in his office and personal quarters.

Among those he hid were Herman Adler and his wife Anita, both members of Vilna’s prewar Zionist movement. Through them, Schmid met with one of the leaders of the nascent Jewish resistance movement in the ghetto, Mordechaj Tenenbaum. The result saw him smuggling Jews out of Vilna to other Jewish cities such as Białystok—places where it was thought the Jews could have a better chance of survival. Schmid also acted as a conduit enabling various resistance groups to establish contact with one another.

Ultimately, Schmid’s actions in hiding Jews, supplying them with false papers, and arranging their escape managed to save the lives of up to 250 men, women, and children. Within resistance circles, news of his activities on behalf of Jews spread; inevitably, he began to be watched more closely by Nazi authorities. The knowledge that he could be found out only emboldened him to work on behalf of Jews with greater determination and audacity.

Inevitably Schmid was found out. In the second half of January 1942 he was arrested, and on February 25 he was summarily court-martialed for high treason. The death penalty was the only possible outcome of such a trial, and on April 13, 1942, he was duly executed by firing squad.

Anton Schmid was an extremely brave human being. He clearly knew that he was placing himself in danger through his actions, and that, if caught, his fate would be sealed. For all that, however, he did not see anything particularly special in what he did. In his last letter to his wife Stefi, written from his prison cell prior to execution, he wrote, “I only acted as a human being and did not want to hurt anyone.” His actions had an unfortunate outcome for Stefi, besides the obvious one of depriving her of her husband, his income, pension, and a war hero’s death. When word got back to Vienna, her neighbors shunned her, referring to her husband as a traitor and socially ostracizing her. At one point, her windows were smashed.

The life-saving deeds of Anton Schmid had another outcome, however, when, on May 16, 1967, Yad Vashem in Jerusalem recognized him as one of the Righteous among the Nations. Stefi Schmid received the award personally, having been flown to Jerusalem for the occasion.

Then, on May 8, 2000, the German government named a military barracks in Schmid’s honor in Rendsburg, northern Germany, as the Feldwebel-Schmid-Kaserne. At the naming ceremony Germany’s defense minister, Rudolf Scharping, said: “We are not free to choose our history, but we can choose the examples we take from that history. Too many bowed to the threats and temptations of the dictator, and too few found the strength to resist. But Sergeant Anton Schmid did resist.”

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Einsatzgruppen; Ponary Forest; Rescuers of Jews; Righteous among the Nations; Vilna Ghetto

Further Reading

Silver, Eric. The Book of the Just: The Unsung Heroes Who Rescued Jews from Hitler. New York: Grove Press, 1992.

Wette, Wolfram. The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 2007.

__________________

Scholl, Hans and Sophie

Hans Scholl and his sister Sophie were a brother and sister who were at the forefront of organizing a resistance movement within Germany against the Nazi regime during World War II. The movement, known as the Weisse Rose (“The White Rose”), was largely centered on the University of Munich, where the Scholls were students.

Hans was born on September 22, 1918, in Ingersheim, the second of six children. Sophie was born on May 9, 1921, in Forchtenberg. Hans joined the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend), and Sophie the League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel) soon after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, and at first they were enthusiastic supporters of the Nazi regime. Their parents, however, were far less enamored with the Nazis and expressed their dissatisfaction to others.

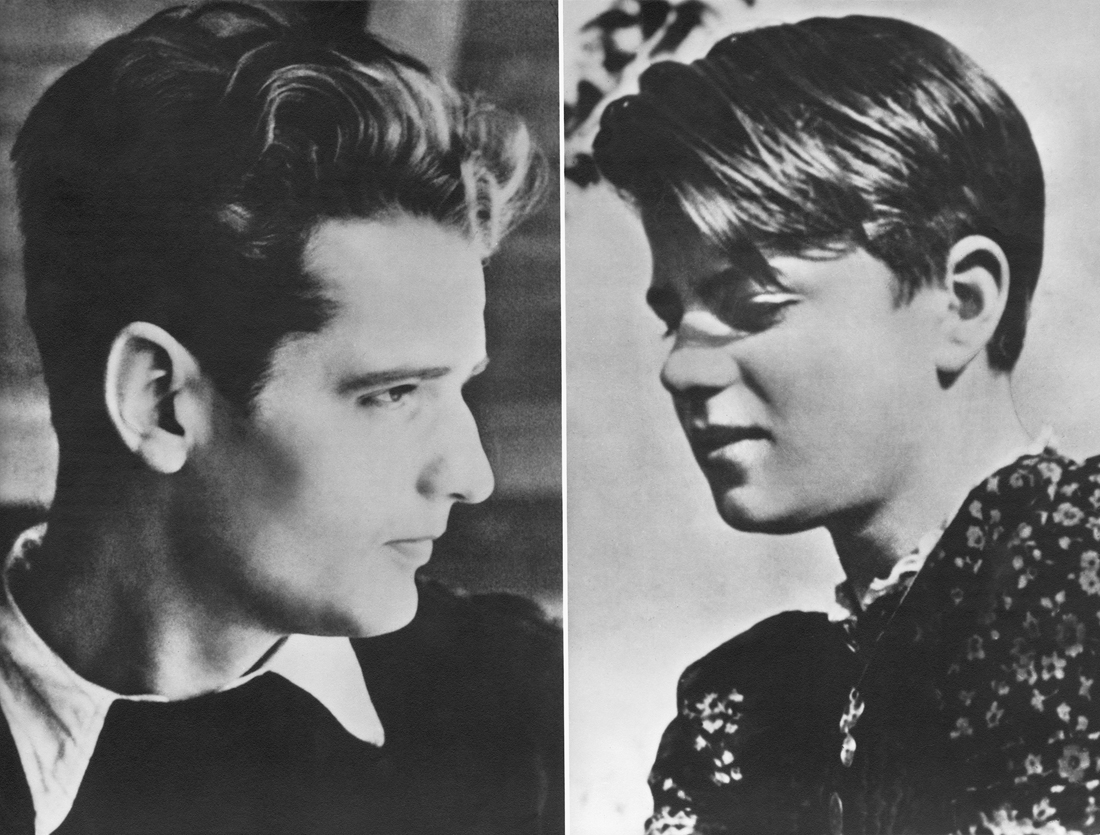

Hans and Sophie Scholl, a brother and sister who, with others, organized the White Rose, an anti-Nazi movement centered among students at the University of Munich. They produced and distributed a series of leaflets condemning Nazism and calling on the German people to rise up against it. Hans and Sophie, together with Christoph Probst, were executed on February 22, 1943; others were later caught and also executed. (Authenticated News/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The younger Scholls became increasingly disenchanted with the Nazi Party during their years at the University of Munich. Hans became a medical student, and Sophie studied biology and philosophy. By the early 1940s they had developed a belief that Hitler and the Nazis were ruining the German nation and engaged in atrocities against Jews and others. They had also come to realize that all Germans had a duty to object to their government’s policies and activities, and their attitudes were reinforced at home; in 1942 their father, Robert Scholl, was arrested for publicly doubting Germany’s ability to win World War II.

In 1942, with a group of fellow students including Christoph Probst, Willi Graf, and Alexander Schmorell, and their professor, Dr. Kurt Huber, the Scholls helped to spearhead the White Rose. The group began posting and mailing various antigovernment posters and literature publicizing the atrocities perpetrated by Hitler’s government, and urging Germans to resist the government and its policies. One of those who met with them and assisted briefly in these early days was a Swedish Red Cross delegate, Sture Linnér.

The focus of these statements was a series of numbered pamphlets campaigning for the overthrow of Nazism and the revival of a new Germany dedicated to the pursuit of goodness and founded on the purest of Christian values. The group’s opposition to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party was essentially based on religious morality and humanitarianism, with little, if any, overt political motivation.

The name of their movement came from a novel that had inspired the Scholls when they were young. Their initial pamphlet, of what would eventually be six, was secretly published in June 1942. The pamphlets attracted public attention, and copies were made and distributed widely. Problems arose regarding state-regulated supplies of paper and ink, which could only be overcome illegally, but eventually White Rose pamphlets were dispersed throughout Germany and Austria, denouncing the activities of the Nazi Party and decrying the murder of innocent German citizens, including Jews.

The activities of the group quickly drew the attention and ire of the Gestapo. Hans, Christoph Probst, and others were sent to fight on the Russian front from the summer of 1942 onward, exposing them to the horrors of the Holocaust and other wartime atrocities. This only encouraged their efforts to resist Nazi authority when they returned to Germany.

The range of the White Rose group expanded beyond the University of Munich. Students at the University of Hamburg also joined, and at its peak membership it had about 80 adherents.

In mid-February 1943 the White Rose arranged a small anti-Nazi demonstration in Munich. Their ideals inspired them to an ever-increasing number of daring acts, such as a run through the buildings of the university during which leaflets condemning the Nazis were scattered liberally in the hallways. On February 18, 1943, a janitor who was a Nazi Party member, Jakob Schmid, spotted Hans and Sophie scattering copies of the sixth pamphlet from a balustrade in the atrium of the university. He raised the alarm, called the Gestapo, and had the Scholls and Probst arrested.

They were sent for a summary trial in the Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) on February 22, 1943, and stood before Judge Roland Freisler, who berated them for their activities. They were quickly indicted for treason, and, defiantly, they admitted their crimes. Inevitably found guilty, Hans and Sophie Scholl, together with Christoph Probst, were executed by beheading the same day. It was noted by witnesses that all three faced their deaths bravely, with Hans claiming as his last words, “Long live freedom!” Hans was 24, Sophie was 21, and Christoph was 22. From arrest to execution took only four days.

Shortly afterward, numerous others associated with the White Rose were denounced, identified, and arrested by the Gestapo. Later that same year, other executions took place. Alexander Schmorell (age 25) and Dr. Kurt Huber (age 49) were both executed on July 13, 1943, and Willi Graf (age 25) on October 12, 1943. Another member, Hans Conrad Leipelt, who helped distribute the sixth leaflet in Hamburg, was executed on January 29, 1945, aged 23. Most of the other students convicted for their part in the group’s activities received prison sentences; many were consigned to concentration camps.

The text of the sixth White Rose leaflet saw their efforts crowned in part, however. It was picked up by Helmuth James von Moltke and smuggled out of Germany, through Scandinavia, to the United Kingdom. In July 1943 tens of thousands of copies of the leaflet were air-dropped over Germany as “The Manifesto of the Students of Munich.”

The White Rose movement and the story of the Scholls have become the subject of numerous depictions in literature and film, most notably two movies: Die Weiße Rose (dir. Michael Verhoeven, 1982) and Sophie Scholl, Die letzten Tage (dir. Marc Rothemund, 2005).

In death, the members of the White Rose became a spur to other anti-Nazi groups as well as the political left throughout Germany. After World War II the movement began to be seen by Germans as an admirable example of resistance to evil. The Scholls have become revered as among Germany’s greatest heroes (particularly among younger Germans), with the White Rose Foundation and White Rose International serving as contemporary organizations that seek to preserve the memory of the White Rose and continue its tradition of “principled resistance.” The bravery of the Scholls and their friends has come to represent individual sacrifice in the midst of unspeakable oppression and evil.

PAUL R. BARTROP

See also: Freisler, Roland; Hitler Youth; League of German Girls; Resistance Movements; Upstander; White Rose

Further Reading

Hanser, Richard. A Noble Treason: The Revolt of the Munich Students against Hitler. San Francisco (CA): Ignatius Press, 2012.

Dumbach, Annette, and Jud Newborn. Sophie Scholl and the White Rose. Oxford: Oneworld, 2007.

Vinke, Hermann. The Short Life of Sophie Scholl. New York: Harper and Row, 1984.

__________________

Scholtz-Klink, Gertrud