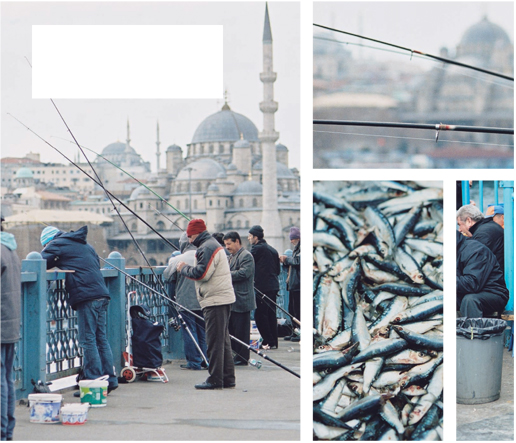

Istanbul is a city dominated by the sea, whose lifeblood has always been the salt water that flows through and around it.

The second night in Istanbul I was awakened in the small hours by squabbling seagulls on the rooftops outside my window. As I peered out into the chilly night, past the looming bulk of the Blue Mosque, I could sense the distant presence of the rain-swept Bosphorus, grey and sullen in the pre-dawn light.

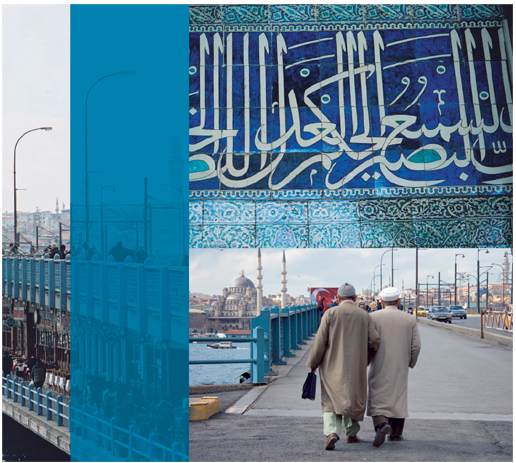

It was a reminder that Istanbul is a city dominated by the sea, whose lifeblood has always been the salt water that flows through and around it. Not only is the city itself split in two by the deep and dark waters of the Bosphorus, but the European side is also rift by a smaller inlet, the Golden Horn. And then there are those two seas: the vast and mysterious Black Sea to the north, and the smaller Sea of Marmara abutting the Aegean, to the south. Few other cities are so advantageously positioned between land and water, or have been fought over so continuously or determinedly through the centuries as a result.

Then, through the squally rain, the mosque’s speaker crackled into life and the first prayer call of the day rose up and out into the lightening sky. There was little chance of getting back to sleep so I stayed in my spot at the window, watching the sky gradually lighten and the wind and rain die down; a good thing, too, as we had plans that day for a boat trip on the Bosphorus.

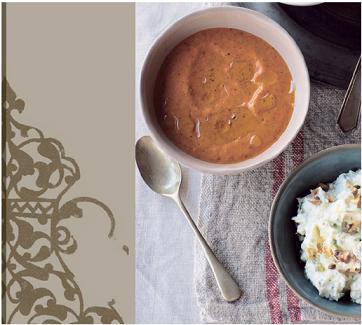

The Galata Bridge was bristling with fishing rods and down on the waterfront the morning’s catch was being hauled ashore to be cooked over wood-fire grills and made into the famous Istanbul fish sandwiches.

This thirty-kilometre strait is famous for being one of the busiest and most difficult-to-navigate waterways in the world. An estimated 50,000 vessels plough back and forth between the two shores and the two seas every year. Tiny one-man rowboats do daily battle with massive freight trawlers and oil tankers, while lumbering old-fashioned commuter ferries, private pleasure boats and fancy cruise ships weave their way around each other.

Later that morning we made our way down to the Eminönü quay to watch the action. The Galata Bridge was bristling with fishing rods and down on the waterfront the morning’s catch was being hauled ashore to be cooked over wood-fire grills and made into the famous Istanbul fish sandwiches. As we pushed our way through the crowds that were bustling around the ferry stations, the aroma of frying fish became too much for us. At a small kiosk, we watched eagerly as a couple of piping hot fish fillets were deftly flipped into bread rolls. We scoffed them down greedily. Now we were ready for our excursion.

Our ferryboat was starting to fill with tourist passengers all set for a day on the water. Its bulky prow rose and fell on the lazy swell of the tide, and hungry seagulls circled, on the hunt for the odd piece of discarded fish sandwich. We clambered aboard and found a well-positioned spot in the front of the boat. The horn blew low and loud; the boat drew away from the quay and the seagulls moved into place, dipping and swooping into the boat’s choppy wake.

For many centuries, before the city began its expansion in earnest, the Bosphorus was a lovely broad waterway, its banks fringed with rolling green hills and thick forests and dotted with pretty little fishing villages. Today, the densely populated suburbs of Istanbul sprawl along its entire length, almost as far as the Black Sea. As the boat began its zig-zag journey, with the smell of brine in our noses, we were filled with a sense of excitement – heading towards the open sea, leaving the chaos of the city behind. And there was an even greater pleasure to be had from seeing that city revealed from a distance, allowing, as it did, an entirely different, more peaceful perspective.

Scenes from everyday Istanbul life, past and present, were unfolding on either side of the strait. We saw modern museums and ornate nineteenth-century palaces, grand hotels, pretty mosques and decrepit apartment buildings that seemed to be collapsing into the water. And on both sides, here and there we passed lovely wooden villas known as yali, with their carved wooden balconies, high shuttered windows and gently sloping roofs. The yali were built by wealthy Ottoman families during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as waterside summer residences, where they would go to escape the sweltering heat of the city. Sadly, many have disappeared completely; others have rotted into ruin. They stand dark and derelict, their once smartly painted woodwork now bleached a dirty grey-brown.

As the boat began its zig-zag journey, with the smell of brine in our noses, we were filled with a sense of excitement – heading towards the open sea, leaving the chaos of the city behind.

Further on, at the narrowest part of the Bosphorus, we passed the crenellated towers and walls of Rumeli Hisari. This mighty fortress was built by Mehmet II in 1452 as part of his highly organised siege of Constantinople. His intention was to cut the city off from any assistance that might arrive by sea, and the plan worked a treat. Within a year the capital was wrenched from Christian Byzantium for ever. But while Constantinople flourished under its new Ottoman rulers, the fortress itself had served its purpose and quickly fell out of use.

We disembarked at Kanlica, a sleepy little village on the Asian side of the Bosphorus famous for its yoghurt. The pretty harbour was encircled by tall timber houses and the water was crowded with brightly painted fishing boats. We wandered around the village square enjoying the sunshine for a while before ducking into a café overlooking the water for some refreshment. We learned that, traditionally, Kanlica yoghurt was made from a mixture of cow’s milk and ewe’s milk and was thick enough to cut with a knife. Today, most of the local product is sold pre-set in tubs and one of the main reasons for its popularity is that it comes ready-sweetened with powdered sugar – something of a novelty in a country where mass-produced, gloopy Western-style yoghurt, thick with artificial fruit flavours and colours, was unheard of until quite recently.

On the menu there was a range of yoghurts we could choose from, either plain or topped with jam, molasses, icing sugar or honey. At the table next to ours, a young couple were scooping up tiny spoonfuls of the stuff and slipping it into each other’s mouths. We smiled at them. They smiled at us. ‘There’s a lot of yoghurt to choose from here,’ we said. ‘Ah yes,’ replied the young man. ‘Turkish people take their yoghurt seriously!’ On their advice we chose the unsweetened variety, which was indeed delicious: brilliantly white, thick and creamy, with a pure, mild flavour. We enjoyed it drizzled with local honey, accompanied by a cup of strong black tea poured from a gently bubbling samovar.

Re-energised, we decided it was time to head back to the city. The Istanbul ferry didn’t call back at Kanlica until much later that afternoon, so, undaunted, we decided to brave one of the busy local buses. More by luck than good planning, we got onto a bus for Istanbul, and were delighted to spot the young yoghurt-lovers from the Kanlica café sitting in front of us. We smiled at each other in recognition and gratefully accepted their help in changing buses at the busy Mecidiyeköy bus station. An hour or so later we passed the massive  nönü football stadium, famous for being the only sporting venue in the world where fans can view two continents simultaneously. There was a match on that evening and it was apparent from the crowd that the supporters had other things on their mind than the view. The police were out in force, clearly anticipating trouble. They took up their places in serried ranks; they all wore visors, with riot shields held high and truncheons at the ready. The young couple in front of us on the bus were amused by the look on our faces. ‘Turkish people take their football seriously!’ they told us.

nönü football stadium, famous for being the only sporting venue in the world where fans can view two continents simultaneously. There was a match on that evening and it was apparent from the crowd that the supporters had other things on their mind than the view. The police were out in force, clearly anticipating trouble. They took up their places in serried ranks; they all wore visors, with riot shields held high and truncheons at the ready. The young couple in front of us on the bus were amused by the look on our faces. ‘Turkish people take their football seriously!’ they told us.

Haydari

Thicker than cacik, this is made from strained yoghurt – süzme – which is very like the Middle Eastern labne. Haydari is often mixed with mild red or green chillies and spread on little toasts or toasted flat bread. It’s also delicious with all sorts of grills – meats, seafood, poultry, köfte and kebabs.

Strained yoghurt is worth making to try in a variety of dips. Try it also with hot and spicy soups or serve as an accompaniment to grilled meats and poultry, rice dishes and even with desserts. This quantity will make about 350 g, enough to make haydari or for you to try both Whipped Fetta Dip and Soft White Cheese and Walnut Dip.

STRAINED YOGHURT

1 kg thick natural yoghurt

1 clove garlic

1 teaspoon sea salt

½ cup finely chopped dill

1 long green chilli, seeded and shredded

sweet paprika to serve

extra-virgin olive oil to serve

To strain the yoghurt, spoon it into a clean muslin or cheesecloth square or tea towel. Tie the four corners together and suspend the bundle from a wooden spoon over a deep bowl. Refrigerate overnight to drain. (You can use the strained yoghurt in other savoury or sweet recipes, and flavour accordingly.)

To make haydari, tip the strained yoghurt into a large bowl. Crush the garlic with the salt, then beat into the yoghurt with the dill and chilli. Taste and adjust seasoning if necessary. Chill, covered, until ready to eat. Transfer to a serving bowl or plate and garnish with a sprinkle of paprika and a drizzle of oil.

SERVES 4–6

Cacik

Although cacik is a popular mezze dish in Turkey, it’s also served as an accompaniment to pastries, meat and rice dishes and can be diluted with ice-cold water to make a refreshing summer soup.

You’ll find cacik flavoured with all sorts of green herbs, but mint or dill are the most commonly used.

Cacik varies in consistency and can be very runny. It is usually made from ordinary natural yoghurt, so if you prefer it thicker, as we do, then use a thick Greek-style or tub-set variety.

1 clove garlic

sea salt

500 g thick natural yoghurt

2 Lebanese cucumbers, seeded and grated (skin on)

cup finely chopped dill

cup finely chopped dill

1 teaspoon dried mint

squeeze of lemon juice

Crush the garlic with 1 teaspoon salt, then beat with the yoghurt, cucumber and herbs in a large bowl. Season with salt and lemon juice to taste. Chill, covered, until ready to eat.

SERVES 4–6

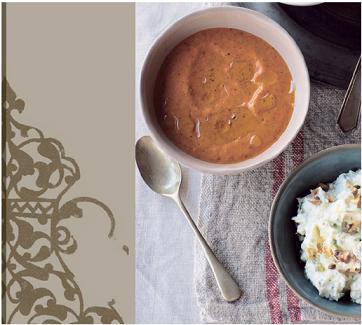

[ Clockwise from left ] Hot Red Pepper Paste, Cacik, Soft White Cheese and Walnut Dip

Yoghurt

A stroll through the dairy section of any Turkish market reveals the Turks as a nation of yoghurt lovers. In fact, most of the country’s milk production goes towards making yoghurt – whether it is from cow, goat, sheep or even water buffalo milk. Turks tend not to use low-fat cow’s milk, and yoghurt devotees will know that the higher fat content of the latter three animals makes even more delectably creamy yoghurt (these are increasingly available in the West). A delicious type of Turkish yoghurt that we discovered on our travels is kaymakli yoghurt, which has a thick layer of clotted ‘cream’ on the surface.

Unflavoured yoghurt appears on the table at every mealtime and is served with just about anything, including soups, stews, kebabs, pilavs, stuffed vegetables and salads. It is often flavoured with garlic and herbs, such as fresh dill and mint, to be made into side dishes like cacik and haydari; or strained to make soft fresh cheese and eaten with jam, honey or icing sugar as a delicious breakfast or snack. And if it’s not being eaten, it’s being drunk as the cooling, slightly salty drink ayran.

Yoghurt is one of the most ancient foods known to man. Evidence exists of fermented milk products being produced almost 4500 years ago, and the Turks are just one of many peoples who like to claim responsibility for its creation. There is no clear proof as to where or how it was first made, but the earliest yoghurts can be traced back to nomadic horse-riding peoples of Central Asia, who made both yoghurt and cheese from milk produced by their small goat and sheep flocks and from their horses. The evidence suggests that milk was often transported in goatskin bags strapped to the saddles, and the earliest yoghurts were probably fermented spontaneously by wild bacteria.

In Turkish markets and dairy shops you’ll generally find two kinds of yoghurt: sivi tas and süzme. Sivi tas is the standard yoghurt and can vary in consistency from fairly runny to thick and creamy; it’s used to make most yoghurt-based sauces and is diluted with iced water to make ayran. Süzme is a very firm, strained yoghurt that’s made by hanging sivi tas in a muslin bag overnight to drain away the whey. The longer the hanging time, the thicker the result. If allowed to drain for a couple of days it becomes a creamy soft cheese with a light tangy flavour; delicious spread on bread with a drizzle of extravirgin olive oil. Sadly, strained yoghurt is not widely available in Western countries, but it is incredibly easy to make your own at home.

Whipped fetta dip

This dip was one of my first-ever creations as a young chef and I still love it. It’s utterly simple, but the balance of salty cheese, hot mustard and tangy yoghurt is just brilliant. Although the mustard is not strictly Turkish, variations of little cheese dips are very popular as part of mezze selections. If you want to add another dimension of flavour, add a teaspoon of mild honey to the processor along with the mustard and strained yoghurt.

Serve this dip with raw vegetables or warm or toasted flat bread. You could even thin it down with olive oil to dress a robust cos lettuce salad.

220 g sheep’s fetta

150 g Strained Yoghurt

1 generous teaspoon Dijon mustard

Soak the fetta in cold water for around 10 minutes to remove excess salt, changing the water twice. Crumble the fetta roughly into a food processor and purée for a minute, pushing the mixture down from the sides once or twice. Add the strained yoghurt and mustard and purée again until very smooth and creamy. Chill, covered, until ready to eat. This dip will keep for up to a week.

SERVES 4–6

Silky celeriac dip with lime

I was inspired to make this dip after a wonderful meal at Istanbul’s famous Do a Balik. Although best known for its seafood, the restaurant also has a mind-bogglingly large number of mezze dishes on display, and diners are encouraged to make their own selection. This unusual dip has a refreshing, mild celery flavour and a delectable silky-smooth texture. The lime juice is not very Turkish, but it adds a lovely citrus zing. Serve as a dip with warm or toasted bread, or as an accompaniment to grills and roasts.

a Balik. Although best known for its seafood, the restaurant also has a mind-bogglingly large number of mezze dishes on display, and diners are encouraged to make their own selection. This unusual dip has a refreshing, mild celery flavour and a delectable silky-smooth texture. The lime juice is not very Turkish, but it adds a lovely citrus zing. Serve as a dip with warm or toasted bread, or as an accompaniment to grills and roasts.

2 celeriac (about 700 g)

2 cloves garlic, peeled and smashed

1 litre milk

juice of up to 1 lime

85 ml olive oil

sea salt

freshly ground white pepper

Peel the celeriac and cut into even-sized pieces. Place in a saucepan with the garlic and milk and bring to the boil. Lower the heat and press a piece of baking paper, cut to the size of the pan, down over the celeriac. Simmer gently, covered, for around 30 minutes, or until the celeriac is very soft.

While the celeriac is still hot, tip it into a vitamiser or food processor with half the cooking liquor and half the lime juice and blitz to a velvety-smooth purée. With the motor running, slowly drizzle in the olive oil to form an emulsion. Season with salt and pepper, then add more lime juice to taste. Chill, covered, until ready to eat.

SERVES 4–6

Hot red pepper paste

On our very first day in Istanbul we ate in a tiny pide restaurant. The first thing to arrive on the table was a small pot of spicy red pepper paste, a dish of butter and a plate of crumbled white lor cheese. We ate these with big puffed-up rounds of flat bread, straight from the wood-fired oven, and thought we’d arrived in heaven. This is our version of the pepper paste – it is quite chilli-hot, so a little goes a long way. Serve it on warm flat bread with chilled unsalted butter and lor. If you can’t get hold of lor, then another crumbly white cheese, such as Wensleydale or a mature goat’s cheese, will do nicely.

3 long red peppers

3 long red chillies, seeded

1 teaspoon pomegranate molasses

½ teaspoon dried mint

2 tablespoons shredded mint leaves

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 spring onions, finely diced

1 small Lebanese cucumber, peeled, seeded and diced

juice of 1 lemon

1 teaspoon sea salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Roast the peppers and seeded chillies for 20 minutes on a foil-lined baking tray, turning once, until the skins blister and char. Remove from the oven and leave to cool.

When cool enough to handle, peel the skins away from the peppers and pull away the seeds and membranes. Roughly chop the peppers and tip into a vitamiser. Use a sharp knife to scrape the flesh of the chillies away from the skins – this is easier than trying to peel them. Add the chilli flesh to the vitamiser with the remaining ingredients. Whiz to a fine purée, then taste and adjust the balance of salt and lemon if necessary. Chill, covered, until ready to eat. This dip will keep for up to 3 days.

SERVES 4–6

Creamy fava bean pâté with grated-egg dressing

When we first saw a slab of this pale green pâté on a tray of mezze dishes in Istanbul’s Refik restaurant, we had no idea what it was. It’s made by pouring a thick bean purée into a mould and chilling it until it sets firm. The resulting pâté has a smooth, creamy texture and its mild flavour is quite addictive. Although the grated egg is not really Turkish, I find it adds colour and texture and an extra flavour dimension.

Serve drizzled with olive oil, chopped dill, paprika and lemon, or, if you want to be a bit fancy, Dill and Lemon Dressing. Cut off little slices and eat with warm or toasted flat bread.

Fava beans are simply dried broad beans, and are available whole (skins on) or split (skinless). Try to find the split skinless kind if you can.

200 g split fava beans

60 ml olive oil

2 onions, chopped

drizzle of honey

1 small clove garlic, sliced

800 ml water

juice of 1 lemon

sea salt

freshly ground white pepper

1 hard-boiled egg, finely grated

extra-virgin olive oil to serve

chopped dill to serve

sweet paprika to serve

pinch of chilli flakes to serve

lemon wedges to serve

Soak the dried beans overnight in plenty of cold water, and remove the skins if necessary.

Heat the oil in a large heavy-based saucepan, then add the onions and sauté for a few minutes over a medium heat. Stir in the honey and sauté for 5 minutes. Drain and rinse the beans and add them to the pan with the garlic, water and lemon juice. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer, uncovered, for around an hour, or until the beans are tender. If there is still liquid in the pan, increase the heat and bubble vigorously until it has evaporated, taking care that the mixture doesn’t stick and burn.

Blend the beans to a smooth purée in a vitamiser. The mixture will be very thick and creamy. Season with salt and pepper. Pour into well-oiled moulds or a greased shallow plastic tray. Chill, covered, overnight.

When ready to eat, turn the pâté out onto a serving plate or cut into little squares or diamond shapes. Scatter on the grated egg, then drizzle with the extra-virgin olive oil and sprinkle on the dill, paprika and chilli flakes. Serve with lemon wedges.

SERVES 4–6

Soft white cheese and walnut dip

Simple to make, this dip is nice and peppery, and the walnuts give it a pleasing crunch. Serve as a spread for fresh crusty bread or smeared on little croutes as an appetiser with pre-dinner drinks.

⅔ cup walnuts

180 g fetta

2 tablespoons Strained Yoghurt

2 tablespoons chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Scatter the walnuts onto a baking tray and roast for 5–10 minutes until a deep golden brown. Tip the nuts into a tea towel and rub well to remove as much skin as possible. Chop the walnuts finely and toss in a sieve to remove any remaining skin and dust.

Put all the ingredients into a large bowl and mash everything together thoroughly with a fork. Taste and adjust the seasoning.

SERVES 4–6

Smoky eggplant purée

A perennial favourite on the mezze table. Serve with crusty bread, or with thin flat bread, opened out, brushed with a little olive oil and baked in the oven until crisp and golden.

1–2 eggplants (about 650 g)

1 small clove garlic sea salt

1 teaspoon extra-virgin olive oil

175 g thick natural yoghurt

juice of ½ lemon

2 tablespoons finely

chopped flat-leaf parsley or mint leaves

Prick the eggplants all over with a fork and sit them directly on the naked flame of your stove top. Set the flame to low–medium and cook for at least 10 minutes, turning constantly until the whole eggplant is charred. Remove from the flame and place on a cake rack in a plastic bag so the juices can drain off. Allow the eggplants to cool for about 10 minutes. (If you don’t have a gas stove, stand the eggplants under the griller, set to high, turning them regularly until charred. You won’t get quite the same smoky flavour, but the effect is reasonable.)

When the eggplants are cool, gently peel away the skin from the flesh, taking care to remove every little bit or the dip will have a bitter burnt flavour. Tip the flesh into a colander, then press gently and leave to drain for 5–10 minutes.

Tip the drained eggplant into a bowl, then crush the garlic with 1 teaspoon salt and beat into the eggplant with the oil, yoghurt and lemon juice. Chill, covered, until ready to eat. Transfer to a serving dish, add extra salt to taste, sprinkle on the herbs and serve.

SERVES 4–6

Taramasalata

The spice bazaar in Istanbul has a section crammed full of little shops selling Russian and Iranian caviar and bottarga – the salted pressed roe from grey mullet. Upmarket Turkish restaurants sometimes sell bottarga, sliced wafer-thin and chilled. Few of us can afford this luxury, but taramasalata is almost as delicious. These days grey mullet roe is scarce and you’re more likely to be able to find smoked cod roe.

Serve with warm or toasted bread.

100 g grey mullet or smoked cod roe

2 thick slices good-quality white bread, crusts removed

1 clove garlic, roughly chopped

juice of 1–1½ lemons

250 ml olive oil

250 ml vegetable oil

100 ml water

Lightly rinse the roe under cold running water.

Chop the bread roughly, then put it into a bowl and pour on enough water just to cover. Leave for a few moments, then squeeze it firmly. Whiz the bread, roe, garlic and the juice of 1 lemon to a paste in a food processor.

Combine the oils and start to drizzle into the processor with the motor running as if making a mayonnaise. Begin with 100 ml, then loosen the mixture with 2 tablespoons water. Continue to add oil and water in similar amounts, and finish with the remaining lemon juice. The purée should be light, fluffy and a delicate, pale-golden pink. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Chill, covered, until ready to eat. The taramasalata will keep for 4–5 days.

SERVES 4–6

Almond tarator

This recipe was developed by my good friend Mick ‘Johnstone’ Van Warmelo, chef at Olive restaurant in Hong Kong, where I consult. It is wonderful served as a dip with raw vegetables or to accompany seafood or lamb dishes, and the garlicky tang is particularly good with Crumbed Lambs’ Tongues.

250 g blanched almonds

3 cloves garlic sea salt

juice of 1 lemon

50 ml champagne vinegar

1 tablespoon honey

4 egg yolks

525 ml olive oil

100–150 ml lukewarm water

freshly ground black pepper

Blitz the almonds in a food processor until roughly crushed. Crush the garlic with 1 teaspoon salt and add to the almonds with the lemon juice, vinegar, honey and egg yolks and blitz until smooth and creamy. With the motor running, slowly drizzle in about half the oil, followed by half the water to loosen and stabilise the mixture. Slowly drizzle in the rest of the oil to form a thick, creamy mayonnaise – add a little more water if it is too thick. Season with pepper and check for salt – you may need to add a little more.

To give the tarator a smoother, finer texture, you can blend the mayonnaise in a vitamiser on high for a few minutes.

MAKES 650 g