We had spent the first few days in Istanbul exploring the city’s past; now it was time to leap into its present.

We had spent the first few days in Istanbul exploring the city’s past; now it was time to leap into its present. This meant a stroll across the Galata Bridge to Beyo lu, where the city leans most determinedly towards Europe.

lu, where the city leans most determinedly towards Europe.

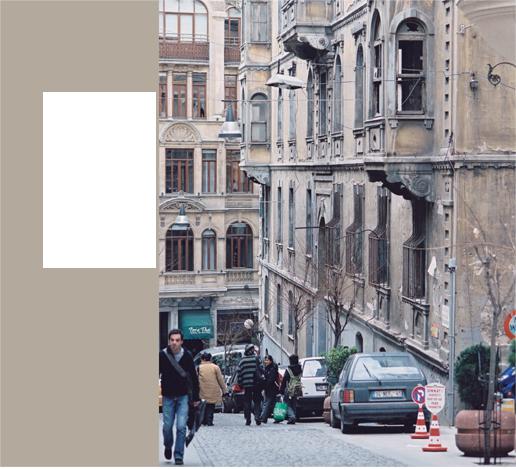

The suburb of Beyo lu encompasses a steep hill on the northern side of the Golden Horn and has always been home to the city’s minority of foreign residents. In the thirteenth century the area was given by the emperor to the Genoese as a gift for their support of Constantinople in its ongoing battles with the Crusaders. Under the Genoese, Pera, as they called it, became a flourishing trading colony, and the Galata Tower, one of Istanbul’s most distinctive landmarks, was built. Over successive centuries, Greeks, Armenians, Arabs and Jews all established communities here. At the height of the Ottoman era, Pera was home to wealthy European merchants, and signs of nineteenth-century grandeur can still be spotted in the neighbourhood’s Beaux Arts, Romanesque and Ottoman architecture.

lu encompasses a steep hill on the northern side of the Golden Horn and has always been home to the city’s minority of foreign residents. In the thirteenth century the area was given by the emperor to the Genoese as a gift for their support of Constantinople in its ongoing battles with the Crusaders. Under the Genoese, Pera, as they called it, became a flourishing trading colony, and the Galata Tower, one of Istanbul’s most distinctive landmarks, was built. Over successive centuries, Greeks, Armenians, Arabs and Jews all established communities here. At the height of the Ottoman era, Pera was home to wealthy European merchants, and signs of nineteenth-century grandeur can still be spotted in the neighbourhood’s Beaux Arts, Romanesque and Ottoman architecture.

Today, as then, istiklal Caddesi is the main thoroughfare. Although it’s no longer the Grande Rue lined with fancy boutiques, fashionable coffee houses and embassies, it still retains some of its former charm. There’s a cute little tram that trundles its way through the thousands of pedestrians; you spy once-glamorous Art Deco facades wedged in between graffitied concrete boxes, while old-fashioned pudding and confectionary shops seem to co-exist quite happily with the predictable chain stores and fast-food restaurants.

We met up with our friend Sedat Arpalik outside Haci Bekir, Istanbul’s most famous Turkish delight shop, and queued behind a smartly dressed businessman with a neatly waxed moustache who was taking his time making a selection from the vast array of exquisitely pretty lokum. But our eyes were drawn to a large pot of warm halva. This was something new, which we couldn’t resist trying. The shop assistant ladled some beige sludge into a small paper cup. It was a little like eating hot, semi-sweet, sesame-flavoured sand – but curiously addictive – and it fortified us against the chilly wind outside.

At the height of the Ottoman era, Pera was home to wealthy European merchants, and signs of nineteenth-century grandeur can still be spotted in the neighbourhood’s Beaux Arts. Romanesque and Ottoman architecture.

Sedat was keen to show us something of Istanbul’s ‘cool’ side. An Australian-born Turk, he’d moved back to the city only a few months before to project-manage a building development.

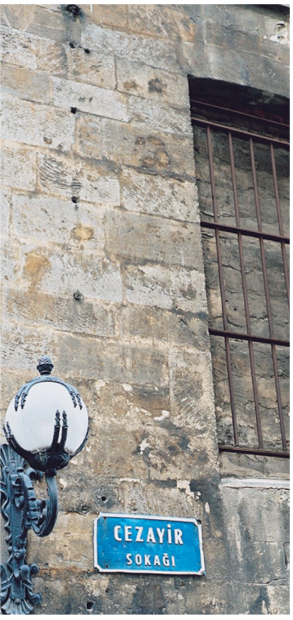

‘There’s definitely a new energy about the place,’ he told us, cutting a path through the crowds and turning down a narrow side street. ‘The neighbourhoods around  stiklal are really funky these days; you’ve got artists, musicians, filmmakers and designers all moving in. And if you think it’s busy now, you should come here at night-time. The place is heaving!’ We were making our way down Nevizade Sokak, Istanbul’s most vibrant eating precinct. ‘I come here most nights for a beer,’ Sedat confessed. ‘In the summer you can barely move for the crowds of people, the wandering gypsy-musicians and street peddlers trying to flog you a rose or two. It’s just wild.’

stiklal are really funky these days; you’ve got artists, musicians, filmmakers and designers all moving in. And if you think it’s busy now, you should come here at night-time. The place is heaving!’ We were making our way down Nevizade Sokak, Istanbul’s most vibrant eating precinct. ‘I come here most nights for a beer,’ Sedat confessed. ‘In the summer you can barely move for the crowds of people, the wandering gypsy-musicians and street peddlers trying to flog you a rose or two. It’s just wild.’

For now, though, we were headed for lunch at Refik, which proved to be far from new and trendy but rather a much-loved fixture on the Istanbul food scene. To get there, we had to pass though Balik Pazari, the district’s famous fish market. All around us were stalls overflowing with spanking fresh sea bass, pimple-backed turbot and huge pans of gleaming blue-black mussels. There were also pickle shops and offal butchers; cheese stalls and kebab stands; hardware stores selling samovars and tea glasses, mops and electric toasters – all the usual stuff of a busy Oriental bazaar.

Refik was an unassuming, homey place, tucked away down a narrow cobbled laneway. We were grateful to step out of the chilly spring air into its cosy, dimly lit interior. Sedat explained that it was one of the city’s oldest eateries, called a meyhane. Meyhanes are traditional inns, serving alcohol alongside small mezze dishes.

‘This place was started more than fifty years ago,’ he said. And as we took our seats under a tatty display of faded black-and-white photographs he pointed out a ruddy-faced man standing by the glassed-in display cabinet. ‘That’s the original Refik,’ he whispered. ‘I believe he’s well into his seventies now but he still comes in every day.’ Mr Refik, looking as if he’d been enjoying a few glasses of raki, the traditional accompaniment to mezze, smiled cheerily and plonked a bottle down in front of us.

A few minutes later a waiter arrived bearing a large tray of tiny mezze plates from which we made our selection: new-season’s artichokes braised in olive oil, a salad of creamy poached brains doused in lemon juice, two slabs of tangy fetta, grilled mushrooms and a bowl of thick mint-spiked yoghurt. These were followed in quick succession by spicy chunks of grilled liver and crisp-fried red mullet. It was all wonderfully fresh, flavoursome and unpretentious.

Warmed by a few glasses of raki we felt ready to head back out into the cold afternoon. Sedat had plans for us, beginning with dessert in a traditional pudding shop. We were easily seduced by the vast trays of sticky, amber quinces served with rich kaymak – clotted cream made from buffalo milk – and a bowl of delicate muhallebi, a milk pudding perfumed with rosewater.

Our tour of Beyo lu continued as we cut back across

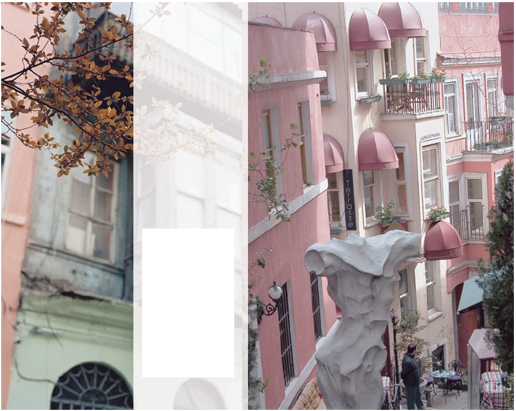

lu continued as we cut back across  stiklal Caddesi to head for Fransiz Soka

stiklal Caddesi to head for Fransiz Soka i, a chi-chi and newly spruced up ‘French’ street, complete with gas street lights, wrought-iron balconies and pretty pink and yellow pastel paintwork. No matter that it all felt just a bit too prettified; at this time of the late afternoon it was busy with young folk out on the terraces enjoying tea, a beer or a quick game of backgammon in the weak sunshine. After dark, Sed told us, diners spill out into the street to enjoy their moules marinières and pommes frites, while the roof-terraces are packed with revellers into the wee small hours.

i, a chi-chi and newly spruced up ‘French’ street, complete with gas street lights, wrought-iron balconies and pretty pink and yellow pastel paintwork. No matter that it all felt just a bit too prettified; at this time of the late afternoon it was busy with young folk out on the terraces enjoying tea, a beer or a quick game of backgammon in the weak sunshine. After dark, Sed told us, diners spill out into the street to enjoy their moules marinières and pommes frites, while the roof-terraces are packed with revellers into the wee small hours.

For now, we forged on to Çukurcuma, which is perhaps the artiest of Istanbul’s trendy neighbourhoods. Its narrow cobbled streets are home to funky little art galleries, pricy antique shops and grungy little dives selling all sorts of bric-a-brac. We clambered over a mound of excavated tarmac where the road was being dug up to lay new electricity cables – par for the course in this city – and almost fell over a film crew filming an episode of a Turkish ‘soapie’. It’s that kind of neighbourhood.

We cut back to head for Fransiz Soka , a chi-chi and newly spruced up ‘French’ street, complete with gas street lights, wrought iron balconies and pretty pink and yellow pastel paintwork.

, a chi-chi and newly spruced up ‘French’ street, complete with gas street lights, wrought iron balconies and pretty pink and yellow pastel paintwork.

Later that night Sed took us to Changa restaurant, where Turkey’s embrace of Europe is most smartly on display. It’s situated just off busy Taksim Square in an area pulsing with neon, nightclubs and greasy doner kebab stands. The traffic was at a standstill as we squeezed our way across the narrow street towards a discreet entrance.

Changa has led the way for modern dining in Istanbul and its sleek minimalist interior within a narrow Art Nouveau townhouse was undeniably alluring. The decor was as cutting edge as anything you’d find in London, Sydney or New York – all chrome, glass and Eames chairs beneath original painted plaster ceilings. It even had a feature glass porthole cut into the ground floor so the foodie customers could spy on the kitchen action beneath their feet. The clientele were clearly a modern kind of Turk, too, with plenty of polo necks and black-rimmed spectacles on display.

Pleasingly, the food lived up to the stylish standard of the restaurant’s design. After studying the menu, it came as no surprise to learn that the famed New Zealand-born fusion-king Peter Gordon had a hand in the menu. As with his other restaurants in London and Auckland, the menu was brimming with original ideas – many with a clear Turkish bent. We shared a soup of swiss chard and sucuk sausage, slices of tongue with a crust of spicy çökelek cheese, a superb confit of duck with a pistachio- and raisin-studded pilav and tender little lamb chops served with a smoked-bulgur pilav.

Changa isn’t the kind of place that your average Turk would rush to. It’s expensive for a start – even for those of us spending a tourist dollar. And Turkish people have a rather protective approach to their cuisine; at heart they don’t really approve of it being messed around with. But Changa’s customers were the sort of well-heeled, Western-oriented set that would happily rush to try something a bit new and different. And they seemed to be enjoying the food immensely, confident that its Turkishness was not being overly compromised.

As we went to hail a taxi, a group of giggling young Turkish women spilled out from a nearby doorway in a cloud of cigarette smoke and doof-doof music. We were intrigued to see another example of the way East and West blend so harmoniously in Istanbul, for although several girls were displaying bare midriffs, a couple of others were wearing headscarfs.

Crunchy zucchini flowers stuffed with haloumi, mint and ginger

12 baby zucchini with flowers attached

vegetable oil

olive oil

plain flour for dusting

2 eggs, lightly beaten with a little water sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

SUMAC CRUMBS

finely grated zest of 2 limes

½ teaspoon chilli powder

1 teaspoon fennel seeds, lightly roasted and crushed

2 teaspoons ground sumac

200 g dried breadcrumbs

HALOUMI STUFFING

100 g haloumi, washed

50 g mozzarella

1 small clove garlic

½ teaspoon salt

generous pinch of ground cardamom

generous grind of black pepper

¼ teaspoon freshly grated ginger

2 tablespoons finely shredded flat-leaf parsley leaves

1 heaped teaspoon finely chopped mint leaves

½ teaspoon dried mint

To make the crumbs, leave the lime zest out on a plate to dry overnight or put it into a very low oven for 30 minutes. This will intensify the lime flavour. Mix the zest with the remaining ingredients and set aside.

To make the stuffing, grate the haloumi and mozzarella into a bowl. Crush the garlic with the salt and stir into the bowl with the remaining ingredients.

Carefully open each zucchini flower and pinch out the stamen. Roll a lump of the cheese stuffing into a thumb-sized sausage shape and gently stuff it into the flower. Twist the top of the flower to seal.

Heat equal quantities of the oils in a deep-fryer or saucepan to 200°C. Set up a little production line of flour, egg wash and the crumb mixture. Dust each zucchini flower lightly with flour, then dip it into the egg and, finally, gently roll it in the crumbs.

Carefully fry the flowers in the hot oil, no more than four at a time, until the crumbs turn crisp and golden. Remove and drain on kitchen paper, and repeat with the remaining flowers. Season lightly and serve straight away.

SERVES 4

mam bayildi

mam bayildi

Purists will have to forgive me for messing around with Turkey’s most famous dish. I love using tiny eggplants, which are the perfect size to serve as an accompaniment to roast or grilled lamb dishes. You could also serve them at room temperature as part of a mezze selection. And as for the goat’s cheese – well, I think it adds an incomparable creamy tang to this luscious dish.

Pekmez, or grape molasses, is available from Turkish food stores. You’ll find the red pepper paste used here in Middle Eastern food stores.

6 small eggplants (8–10 cm long) sea salt

olive oil

100 g soft goat’s cheese

GARLIC PASTE

1 tablespoon olive oil

5 cloves garlic, sliced

2 teaspoons ground coriander

1 teaspoon sea salt

SPICY TOMATO SAUCE

60 ml olive oil

1 large onion, finely diced

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon mild Turkish red pepper paste

6 vine-ripened tomatoes, skinned, seeded and chopped

¼ cup finely chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

1 tablespoon finely chopped French tarragon

zest of ½ lemon

1 tablespoon pekmez

100 ml water sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

Slit the eggplants in half lengthwise from the base to 1 cm below the stalk. Ease each one open – keeping it joined at the stalk – and use the tip of a small sharp knife to score the flesh inside. Sprinkle one side generously with salt and squeeze the eggplant together, then leave to drain in a colander for 30 minutes. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 180°C.

Rinse the eggplants thoroughly, then sprinkle them inside and out with oil. Arrange in a baking tray and roast for 10 minutes. Transfer the eggplants to a container with a lid, then seal and leave to steam and cool down.

To prepare the garlic paste, heat the oil in a heavy-based frying pan. Add the garlic and sauté for a few minutes, taking care not to let it colour. Tip into a mortar with the coriander and salt and grind to a thick paste.

To make the sauce, heat the oil in a heavy-based frying pan and sauté the onion until soft and translucent. Stir in the paprika and pepper paste and sauté for another 2 minutes, then add the tomatoes, herbs, lemon zest, pekmez and water and season with salt and pepper. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer, uncovered, for an hour, stirring occasionally. It should reduce to a very thick, sticky sauce. Refrigerate until needed.

When ready to cook the imam bayildi, preheat the oven to 180°C. Arrange the eggplants in a large baking dish. Carefully lift up the top half of each eggplant and smear a little garlic paste inside, pushing it down into the soft flesh. Smear a heaped spoonful of sauce inside each eggplant as well and dab in a little goat’s cheese. Press the top down again to form a kind of sandwich. Drizzle with oil and bake for 10–12 minutes until the sauce is bubbling and the cheese oozing. Allow to cool and serve cold or at room temperature.

SERVES 6

Braised broad beans with artichokes and pastirma

Fresh broad beans cooked in olive oil are a popular mezze dish in Turkey. Sometimes they are cooked and eaten in the furry outer pod, especially in the Aegean region, but podded or whole they are usually flavoured with fresh dill. In this recipe I have taken inspiration from a Spanish dish and substituted pastirma – the spiced, cured beef popular across Turkey – for the more traditional jamon iberico.

Serve these beans cold or warm as part of a mezze selection, with crusty bread to mop up the juices.

300 g fresh broad beans in the pod, shelled

1 clove garlic

½ teaspoon sea salt

80 ml extra-virgin olive oil

6 fresh artichoke hearts, cut into quarters and kept in acidulated water

12 pearl onions, peeled and halved

1 teaspoon dried mint

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 sprig thyme

150 ml Chicken Stock

juice of ½ lemon

2 tablespoons chopped dill

100 g pastirma, shredded

Blanch the broad beans in a saucepan of boiling water and refresh briefly under cold water. When cool, peel off the skins.

Crush the garlic with the salt. Heat 60 ml of the oil in a heavy-based frying pan and add the drained artichokes, pearl onions and garlic and salt. Sauté over a low heat for a few minutes, then add the mint, pepper, thyme, stock and lemon juice. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer, uncovered, for 8–10 minutes, until the artichokes and onions are tender. Add the beans and dill and cook for a further minute, then tip into a warmed serving bowl.

Heat the remaining oil in a separate frying pan. Fry the shredded pastirma until golden brown, then remove from the heat and drain off any excess oil. Scatter over the beans and serve straight away.

SERVES 6

Bitter greens, artichokes and shallots with poppyseeds

This dish was inspired by one we ate at Çiya restaurant in Istanbul. There were many mezze dishes of wild greens we enjoyed that day but we fell in love with the combination of strong, bitter greens and the barely discernible nutty crunch of poppyseeds. In this version a squeeze of lemon juice and a knob of butter at the end soften the bitterness. Serve this dish warm or at room temperature as part of a mezze selection. It also makes a great lunch dish with a poached or fried egg and some warm flat bread.

60 ml extra-virgin olive oil

6 fresh artichoke hearts, cut into quarters and kept in acidulated water

12 small shallots, peeled and halved

1 leek, white part only, cut lengthwise into thin strips and washed

1 teaspoon poppyseeds, lightly crushed

¼ teaspoon hot paprika

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper ground sumac

600 g chicory, roots trimmed

500 g silverbeet, shredded lengthwise

150 ml Chicken Stock

squeeze of lemon juice

40 g unsalted butter

Heat the oil in a heavy-based saucepan and add the drained artichokes, shallots and leek. Sauté over a low heat for a few minutes, then add the poppyseeds, paprika, pepper and 1 teaspoon sumac and cook for a further couple of minutes. Add the chicory, silverbeet and stock. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer, uncovered, for 8–10 minutes until the artichokes and onions are tender.

Remove the pan from the heat, then stir in the lemon juice and butter well and tip into a warmed serving bowl. Sprinkle with a little more sumac and serve.

SERVES 6

‘Turlu’ vegetable pot

‘Turlu’ is the Turkish word for mix, and this vegetable dish is the Turkish equivalent of ratatouille. It is wonderful made when summer vegetables are at their peak. Serve warm, as a vegetarian main course, and accompany with plenty of yoghurt on the side and crusty bread to soak up all the juices.

The pickled green chillies mentioned can be made following the recipe, or they can be bought from a deli.

1 zucchini, cut into 1 cm dice

1 eggplant, peeled and cut into 1 cm dice sea salt

1 carrot, cut into 1 cm dice

2 kipfler potatoes, peeled and cut into 1 cm dice

2 artichoke hearts, cut into quarters and kept in acidulated water

1 small purple onion, cut into 1 cm dice

2 cloves garlic, finely sliced

2 long red peppers, roasted, peeled and cut into 2 cm dice

2 pickled green chillies, shredded

2 vine-ripened tomatoes, skinned and chopped

1 tablespoon coriander seeds, lightly toasted and crushed

good pinch of ground allspice

good pinch of ground cinnamon

freshly ground black pepper

60 ml olive oil

150 ml water

2 tablespoons apple or champagne vinegar

1 teaspoon sugar

1 cup cooked chickpeas

zest and juice of ½ lemon

½ cup chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

Toss the zucchini and eggplant with 2 teaspoons salt and transfer to a colander. Leave to drain for 30 minutes, then rinse thoroughly and pat dry.

Using your hands, toss all the vegetables in a large bowl with the spices and oil. Heat a heavy-based frying pan and sauté the coated vegetables in batches over medium heat until lightly golden.

Transfer the vegetables as they are done to a large casserole dish, then lastly add the water, vinegar and sugar. Stir gently and bring to the boil. Lower the heat, then cover and cook gently for 30–40 minutes or until tender. Towards the end of the cooking time, stir in the chickpeas.

Remove the pan from the heat, then taste and adjust the seasonings. Add the lemon zest and juice and the parsley and serve.

SERVES 4

Large mushrooms baked with smoky chilli

This makes a wonderful, hearty winter lunch dish that you could serve on its own with a big blob of yoghurt and perhaps a simple green leaf salad. It also makes a great accompaniment to a grilled steak or roast – slice the meat and serve it on top of the baked vegetables so the juices intermingle.

50 ml olive oil

1 large purple onion, cut into large dice

2 cloves garlic, roughly smashed

½ teaspoon smoky paprika

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 tablespoon sherry vinegar

6 large mushrooms, stems removed

2 vine-ripened tomatoes, cut into quarters

2 long red chillies, split and seeded

2 long green chillies, split and seeded

few sprigs thyme sea salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

50 g butter 100 ml water

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Heat the oil in an ovenproof frying pan. Add the onion, garlic and spices and sauté for around 5 minutes until soft. Stir in the vinegar.

Place the mushrooms on top of the onions, stem-sides up, and tuck the tomatoes, chillies and thyme in and around them. Season with salt and pepper and scatter bits of butter over the mushrooms. Pour in the water and transfer to the oven. Bake for 20 minutes, or until the vegetables are tender.

Stand the pan over a high heat on the stove. Spoon the juices over all the vegetables so they are moist, and cook vigorously until you are left with a concentrated sauce. Taste and adjust the seasoning and serve straight away.

SERVES 6

Vegetables

While the eggplant is unquestionably king in Turkish cooking, the Turks, in fact, use a veritable cornucopia of vegetables. Which is not surprising really, when you consider that Turkey’s vast landmass covers a diverse range of geographical terrains and climates – from the sun-kissed Mediterranean to lush valleys and mountain pastures and the fertile plains of central Anatolia.

Turkish cooking is mainly based upon the seasons, and this is especially true when it comes to fruit and vegetables (although some, like onions, garlic, potatoes and fresh herbs are grown all year round). Artichokes and broad beans signal the arrival of spring; in the summer, eggplant, okra, tomatoes, peppers and zucchini are at their plump, tasty best; while in the autumn and early winter people make good use of cabbages and celeriac, pumpkins, leeks, carrots and spinach.

A very popular way to cook vegetables is in olive oil – a distinct category of dishes known as zeytinya li – and usually served at room temperature as part of a mezze selection, or on their own, with plenty of crusty bread to mop up the lusciously oily cooking juices. This method of cooking is generally agreed to have been encountered by the Turks after settling in Anatolia. Olive trees had long been cultivated along the Mediterranean and Aegean coastlines by the early indigenous peoples: the Greeks and the Romans. And it is in these regions that zeytinya

li – and usually served at room temperature as part of a mezze selection, or on their own, with plenty of crusty bread to mop up the lusciously oily cooking juices. This method of cooking is generally agreed to have been encountered by the Turks after settling in Anatolia. Olive trees had long been cultivated along the Mediterranean and Aegean coastlines by the early indigenous peoples: the Greeks and the Romans. And it is in these regions that zeytinya li dishes are most widespread.

li dishes are most widespread.

Like other Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern peoples, the Turks also have a passion for stuffing vegetables with herby rice or meat mixtures. These are known as dolma, which in Turkish means stuffed or filled, and the most popular vegetable dolma are made with eggplants, tomatoes, zucchinis and peppers. If a vegetable is wrapped around a stuffing, such as cabbage, spinach or vine leaves, it is known as sarma. Meatless dolmas and sarmas are best served at room temperature or cold, and meat-filled versions are usually served warm. Both may be eaten with a yoghurt sauce.

Given the seasonal nature of Turkish produce markets, it’s not surprising that many vegetables are dried and pickled to be used during the winter months. Long garlands of dried eggplant, okra, peppers and chillies adorn the bazaars, and in villages they dangle from windows or balconies. Tursu – or pickled vegetables – are another standard pantry item. Made by immersing raw vegetables in a flavoured pickling solution, they make a wonderful appetite stimulant at the start of many a meal.

Stuffed vine leaves, Istanbul-style

There are numerous versions of stuffed vine leaves to be found all around the Middle East and Mediterranean. According to Claudia Roden in A New Book of Middle Eastern Food, they were served at the court of King Khusrow II in Persia as early as the seventh century, subsequently spreading through the Muslim world and then the Ottoman Empire.

In Turkey, stuffed vegetables that are rolled, such as vine, cabbage or silverbeet leaves, are known as sarma. This version is especially popular in the summer, when it is served at room temperature as part of a mezze selection.

750 g jar preserved vine leaves or about 500 g fresh vine leaves, washed

100 ml olive oil

¼ cup pine nuts

1 large onion, finely chopped

1 level teaspoon ground allspice

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 level teaspoon dried mint

¼ cup currants

250 g short-grain rice sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

250 ml Chicken Stock

1 vine-ripened tomato, grated

2 tablespoons finely chopped dill

2 tablespoons finely chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

1 lemon, sliced

200 ml hot water

juice of 1 lemon

If using preserved vine leaves, soak them for 10 minutes, then rinse and pat dry. Fresh vine leaves should be blanched in boiling water for 30 seconds and refreshed in cold water.

To make the filling, heat half the oil in a heavy-based saucepan. Sauté the pine nuts for a few minutes over medium heat until golden brown. Add the onion and sauté until softened, then add the spices, dried mint, currants and rice and season with salt and pepper. Stir well and add half the chicken stock to the pan. Cook over a low heat, for 5 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add the remaining stock and cook for a further 5 minutes, or until the stock has been absorbed. Remove the pan from the heat and stir in the grated tomato and fresh herbs.

Line the bottom of a heavy-based casserole dish with a few vine leaves and slices of lemon. Arrange the remaining leaves over a work surface, vein-side up, and cut away the stems. Place a spoonful of the filling across the base of the leaf. Roll it over once, then fold in the sides and continue to roll it into a neat sausage shape. The sarmas should be around the size of your little finger – don’t stuff them too tightly or they will burst during the cooking. Continue stuffing and rolling until all the filling has been used.

Pack the stuffed vine leaves into the casserole dish, layering them with more lemon slices, then pour in the hot water, lemon juice and remaining oil. Place a small plate on top of the sarmas to keep them submerged in the liquid, then simmer gently, covered, for 30 minutes. Check whether the sarmas are ready – if there is still liquid, return the dish to the heat and simmer for another 15 minutes, then check again.

Leave the sarmas to cool in the casserole dish. When ready to serve, turn them out onto a large platter.

SERVES 6–8

Baby carrots and leeks cooked in olive oil with orange peel and spices

To be honest it’s not terribly Turkish to use wine in cooking, but I really love this method of slowly braising vegetables in an oil-rich, flavoursome pickling liquor. It works well for all sorts of vegetables, and you can vary the spices and aromatics to suit. Here I use orange, cardamom and coriander, which go particularly well with the carrots. You can strain, freeze and re-use the cooking liquor for other braised vegetable dishes.

Serve this versatile dish as part of a mezze selection. It also makes a good accompaniment to grilled chicken or lamb, or to baked fish, such as Roasted Whole Baby Snapper with Almond and Sumac Crumbs.

10 baby carrots

4 small leeks, white part only

4 long red chillies

4 cloves garlic, peeled

long piece of peel from 1 orange

2 bay leaves

few sprigs thyme

½ teaspoon dried mint

5 cardamom pods 1 teaspoon coriander seeds, lightly crushed

½ teaspoon black peppercorns, lightly crushed

juice of 3 lemons

400 ml dry white wine

500 ml water

400 ml extra-virgin olive oil

½ teaspoon salt

Scrape the carrots, then trim off the stalks and cut them in half lengthwise. Split the leeks, keeping them attached at the root end, then carefully rinse under running water to remove any lingering dirt. Cut away the root end, then cut the leeks in half crosswise so they are around the same length as the carrots. Split each piece lengthwise. Split the chillies lengthwise, leaving them attached at the stalk. Use the point of a sharp knife to scrape out the seeds.

Put the carrots and leeks into a large, heavy-based, non-reactive saucepan. Add the remaining ingredients and stir well.

Press a piece of baking paper, cut to the size of the pan, down over the vegetables. Bring to the boil, covered, then lower the heat and cook at a very gentle simmer for 25–30 minutes, or until the carrots are tender. Remove the pan from the heat and leave the vegetables to cool in the liquid.

When ready to serve, lift the vegetables from the poaching liquor to a platter – you may want to discard the peel and other larger herbs and spices. Strain the poaching liquor and refrigerate or freeze it for later use.

SERVES 4

Celeriac, potatoes and bitter greens in oil

In Turkey, especially around the Aegean, there are literally hundreds of varieties of wild greens. Almost none of these are available commercially in Australia because we don’t accord them the same value. If you know a forager, or have Greek, Turkish or Italian friends, they may be able to help you out with a secret supply, but otherwise bitter greens such as chicory and rapé work pretty well.

As with the recipe for Baby Carrots and Leeks Cooked in Olive Oil with Orange Peel and Spices (opposite), you can strain, freeze and re-use the cooking liquor for other braised vegetable dishes.

Serve warm or cold as part of a mezze selection, with plenty of crusty bread for mopping up the juices.

350 g small kipfler potatoes, peeled

1 celeriac (about 500 g)

juice of 3 lemons

400 ml white wine

500 ml water

400 ml extra-virgin olive oil

1 sprig thyme

2 bay leaves

1 tablespoon coriander seeds, lightly crushed

1 teaspoon fennel seeds, lightly crushed

½ teaspoon black peppercorns, lightly crushed

½ teaspoon sea salt

1 purple onion, cut into 1 cm dice

200 g rapé, roughly sliced

200 g chicory, roughly sliced

cup chopped dill

cup chopped dill

Cut the potatoes lengthwise into thickish slices. Peel the celeriac and trim the sides to form a rough cube. Cut into five even slices, then cut each slice into sixths. Keep the celeriac in a bowl of acidulated water to stop it discolouring.

Put the lemon juice, wine, water and oil into a large, heavy-based saucepan, and bring to the boil. Add the herbs, spices and salt and stir well. Add the celeriac, potatoes and onion to the pan and simmer for 8 minutes. Add the greens and increase the heat. Boil vigorously for a few minutes until the greens have wilted. Reduce to a simmer, then press a piece of baking paper, cut to the size of the pan, down over the vegetables. Simmer, covered, for 10–15 minutes, or until the potatoes and celeriac are tender. Remove the pan from the heat and leave the vegetables to cool in the liquid.

When ready to serve, lift the vegetables from the poaching liquor to a platter – you may want to discard the larger herbs and spices. Strain the poaching liquor and refrigerate or freeze it for later use.

SERVES 4

Baby beets in a herbed dressing

Dress the beets in this wonderful sharp, herby dressing while warm from the oven and serve at room temperature. They are equally good as a vegetable accompaniment to roasts, barbecues or grills or as part of a mezze selection.

2 bunches baby beetroot (about 600 g)

4 cloves garlic, roughly smashed sea salt

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

2 shallots, peeled and finely sliced

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

100 g fetta, roughly crumbled

HERBED DRESSING

1 clove garlic

1 teaspoon sea salt

juice of 1 lemon

30 ml olive oil

30 ml walnut oil

1 tablespoon dried oregano

¼ cup chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

baby soft herb leaves to garnish (optional)

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Wash the beetroot thoroughly to remove any grit, paying special attention to the area close to the stalks. Trim the roots and cut off the stalks, leaving about 3 cm attached. Place in a baking tray and scatter in the garlic cloves. Season lightly with salt, then add the oil and toss thoroughly. Cover the tray loosely with foil and roast for 30–45 minutes, until the beets are tender.

While the beets are cooking, start making the dressing. Crush the garlic with the salt, then whisk this with the lemon juice and oils.

Remove the tray from the oven and discard the garlic. When the beetroot are just cool enough to handle, peel them and cut them in half lengthwise. Place in a large bowl with the shallots and season with salt and pepper. Add the herbs to the dressing, whisk, and pour onto the beets. Check the seasoning, then add the crumbled fetta and toss gently. Garnish with baby herb leaves, if using. Serve warm or cold.

SERVES 4

Zucchini Fritters with Dill

Zucchini fritters with dill

These little fritters are a very popular mezze dish in Turkey, and are often served at room temperature. They also make a great family supper, hot and crisp from the pan and served with lemon wedges and a yoghurt-based sauce, such as Cacik or Haydari. Better still, they are a great way of using what otherwise can be a rather dull vegetable.

600 g zucchini sea salt

1 small onion, grated

1 small clove garlic, finely chopped

100 g fetta, crumbled

¼ cup finely chopped dill

2 tablespoons finely chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

2 eggs, well beaten

cup plain flour

cup plain flour

2 tablespoons rice flour

freshly ground black pepper

olive oil

Grate the zucchini coarsely and put into a colander. Sprinkle lightly with salt and toss, then leave for 20 minutes to drain. Rinse the zucchini briefly, then squeeze it to extract as much liquid as you can and pat dry with kitchen paper.

Mix the zucchini with the onion, garlic, fetta, herbs and eggs in a large bowl. Sift on the flours, then season with pepper and stir to combine.

Heat a little oil in a non-stick frying pan over medium heat until sizzling. Drop small tablespoons of batter into the hot oil and flatten gently. Cook for 2 minutes on each side, or until golden brown. Drain on kitchen paper and serve piping hot.

MAKES 16

Creamy pepper and pastirma braise

A quick and easy dish that’s good with all sorts of roasts and grills. Try it with Grilled Lamb Cutlets with Mountain Herbs or any grilled kebabs. It would also be delicious served with Everyday Orzo Pilav – you can leave out the pastirma to make a tasty vegetarian meal.

40 g butter

1 large purple onion, diced

3 long green peppers, seeded and diced

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 teaspoon coriander seeds, lightly crushed

1 vine-ripened tomato, skinned, seeded and diced

100 ml thickened cream

sea salt

freshly ground white pepper

30 g pastirma, shredded

finely grated zest of ½ lemon

flat-leaf parsley leaves, shredded, to garnish

Melt the butter in a large, heavy-based frying pan. Add the onion, peppers, garlic and coriander seeds and sauté for 5 minutes, or until the vegetables start to soften. Add the tomato and cream to the pan and stir well. Simmer very gently for 8–10 minutes until the peppers are really tender. Taste and add salt and pepper if necessary, then stir in the pastirma and zest. Serve garnished with parsley.

SERVES 6