The western coast of Turkey has drawn travellers for centuries, keen to explore its extraordinary natural beauty and its famous ancient ruins.

Tempers and emotions were running high among our fellow travellers as we boarded the late-night plane to Edremit from Atatürk Airport. It was a Friday, and Istanbul’s famously bad traffic had been magnified a hundred times by the fact that it was Mevlid-i Nebi, the Prophet’s birthday. The roads were jammed with people heading home to their families for celebratory feasting, and we had made the flight by the skin of our teeth.

It was past midnight by the time we landed at the small country airport. Outside in the still blackness the chilly air was thick with the pungent smell of olives; it felt damp, dense and oily on our faces. We were in the Aegean region, Turkey’s western shoreline – not just the land of the olive tree, but also the birthplace of European civilisation.

The western coast of Turkey has drawn travellers for centuries, keen to explore its extraordinary natural beauty and its famous ancient ruins. In Greek and Roman times these shores were the centre of the classical world and the site of some of its most revered cities. This was the land of Homer’s heroes and the scene of legendary battles; it was the birthplace of Herodotus, the ‘father of history’ and the place where Cleopatra met Anthony.

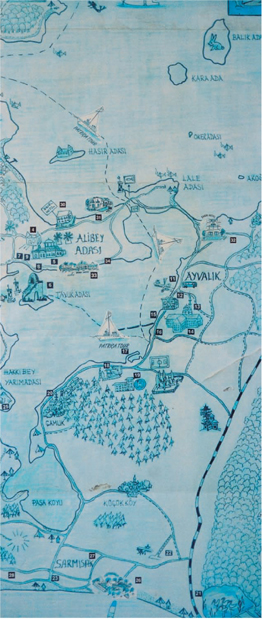

We were staying in Ayvalik, a lively fishing town forty minutes south of Edremit. As we sped south along the highway we could just make out the shadowy shapes of olive groves that fringed the road. Suddenly the moon emerged from behind a bank of dark cloud, and there in the distance we glimpsed the Aegean Sea, shimmering silver in the pale moonlight.

Our friend Tara, an Istanbul resident for eighteen years, had invited us to stay in her old Greek-style house for the weekend. This was her bolthole from the big city, her pride and joy, and she’d spent the last ten years or so gradually renovating the once dilapidated building. Until ninety-odd years ago, Ayvalik was predominantly a Greek town and traces of this heritage are still clearly visible in the old Orthodox churches and traditional Greek stone houses, like Tara’s, that climb up the steep hillside in the old part of town.

The next morning dawned grey, wet and cold. We peered gloomily out of the window at the sleeting rain, which seemed to make a mockery of Herodotus’ claim to this being ‘the most beautiful sky and best climate in the world’. On the upside, it was perfect weather for soup and our friend Tara knew just the place.

Rugged up against the chill we trudged down the steep cobbled streets to Ayvalik’s broad harbour. Rain-lashed and iron grey, only a few diehard fishermen were out on their boats and the waterfront cafés were deserted. Tucked away in a backstreet, we ducked in out of the rain to Erdogan and Neslihan Kapukaya’s small soup restaurant. Inside it was warm and snug, the windows fogged up from the collective breath of family groups happily slurping up the day’s offerings.

A popular local haunt, the restaurant’s specialty was indeed its soups. Neslihan, a rosy-cheeked, smiling woman, was standing behind the counter stirring a number of steaming cauldrons. Today’s specials were: chicken broth, thick with vermicelli pasta; a sludgy brown lentil soup; a pale soup of veal brains, thickened with yoghurt and egg yolks; and a hearty veal tongue and vegetable soup. Naturally we wanted to try them all!

We squeezed into a corner table and Erdogan came rushing up to greet Tara. Rattling off a few sentences in Turkish, Tara made the introductions. Erdogan was amused that we had come all the way from Australia to find ourselves in his small restaurant. Within moments, three little plates appeared on the table: a tangled mound of wild greens, glistening with oil, a bowl of thick garlicky yoghurt and a dish of green olives. Next was the soup – all four varieties for us to try. And finally, thick slices of crusty white bread to mop it all up.

We were stunned to see so many different kinds of ‘wild greens’ on display. As well as the varieties we recognised, there were the more exotically named golden thistle, feverfew and curledock, knotweed and glasswort.

The soups were garnished with wedges of lemon and on the table was a dish of finely ground chilli flakes, a little jug of garlic water and another of vinegar. These are the traditional accompaniments for soup, intended to sharpen the flavour as well as the appetite of the diner. All were excellent: the brain soup, chock-full of slices of creamy offal, its mild flavour enhanced by Erdogan’s suggestion of vinegar and garlic; the hearty tongue soup, thick with gelatinous shreds of meat as well as vegetables and rice; the chicken broth, clear and bursting with flavour; and the traditional lentil soup, properly brought to life by a squeeze of lemon and a dusting of chilli.

By now the weather had improved – there were even welcome signs of sunshine breaking through the clouds – so we headed out to explore Ayvalik further. The narrow streets were filling with shoppers and we decided we needed to stock up on provisions ourselves. In the small marketplace we found more than twenty different varieties of local olives, and huge tins of olive oil. There were fresh white cheeses and creamy kaymakli yoghurt, another specialty of the region, with a thick ‘clotted’ layer on its surface. We were stunned to see so many different kinds of ‘wild greens’ on display. As well as the varieties we recognised, such as purslane and chicory, zahter and watercress, there were the more exotically named golden thistle, feverfew and curledock, knotweed and glasswort. To complete our purchases we bought soft, cheese-stuffed buns for the next day’s breakfast, and a bottle of raki for dinner.

We were dining that evening with another friend of Tara’s, Hüsna Baba, who runs a popular meyhane restaurant tucked away in a shaded alleyway near Ayvalik’s marketplace. Inside, the small front room was crowded with tables of men, their eyes fixed on a massive television set. But they looked over and greeted us with a friendly ‘Merhaba’ as we came in out of the cold. To the rear was Hüsna Baba’s small galley kitchen, and we breathed in the tantalising smell of frying fish. As honoured guests we were seated in the second, larger room. Another long table was set for a group of scuba divers from the local diving school – regulars at Hüsna Baba’s place.

Hüsna Baba was a small dapper man, with a sweet smile and big mournful eyes. After settling us in with glasses and ice for our raki, he started feeding us. The menu was heavily oriented towards seafood, cooked in a simple, no-nonsense Mediterranean style. Hüsna Baba bought his fish fresh every day, straight off the boat, so the menu varied depending on the day’s catch. That evening we feasted on little grilled barbunya (red mullet), calamari rings and tiny slivers of deep-fried mullet roe. A real treat was a dish of brilliant-orange sea urchin corals. We smeared the soft flesh onto white crusty bread, squeezed on a little lemon juice and tasted the briny flavour of the sea.

Later that evening the raki had made us all mellow and the scuba divers at the next table were our new best friends. There had been several toasts to Turkey and Australia and the divers posed enthusiastically for photographs. As we said our goodbyes one of the divers grabbed my arm. Leaning towards me, just a touch too eagerly, he whispered in my ear that somewhere out there, deep beneath the silvery Aegean waters, lay the lost city of Atlantis. It could have been the raki talking, but actually I think he was just pulling my leg.

Pressed quail, liver and pastirma terrine with spiced almond butter

This is a fairly complex restaurant-style dish, but it is a wonderful way to use strongly flavoured pastirma – Turkish air-dried beef – and makes a stunning dinner party starter. Ask your butcher nicely to bone the quail for you, unless you feel confident about doing it yourself.

I like to serve this with a herb salad dressed with a tangy vinaigrette dressing, garnished with pomegranate seeds if in season.

10 baby leeks

100 ml olive oil

1.25 kg chicken livers, cleaned of sinew, blood and fat

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

4 quail, boned and left whole

125 g pastirma, very finely sliced

SPICED ALMOND BUTTER

60 g blanched almonds

¼ cup sesame seeds

2 heaped tablespoons ground coriander

1 heaped tablespoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon hot paprika

½ teaspoon sea salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

200 g unsalted butter, softened

1 teaspoon thyme leaves

To make the spiced butter, dry roast the almonds in a frying pan over a low heat until golden brown, then tip onto a plate and repeat with the sesame seeds. Pulse the almonds and sesame seeds in a food processor until coarsely ground. Add the spices, salt and pepper and pulse until finely ground. Be careful not to overgrind or the mixture will become an oily paste. Tip the spice mix into a bowl and, using a fork, mash in the butter until smooth and homogeneous. Refrigerate until ready to use.

Trim the tops of the leeks neatly and rinse well to get rid of any lingering dirt. Steam the leeks until tender, then drain and leave to cool.

Heat a large, heavy-based frying pan over a high heat until almost smoking. Add a few tablespoons of the oil to the pan, followed by a third of the livers. Seal the livers all over until a good colour – no more than 2 minutes in total, to keep them medium rather than overcooked – and season with salt and pepper. Remove the livers immediately to a wire rack and repeat with the remaining livers, adding more oil to the pan as required. Reserve the cooked livers until ready to assemble the terrine.

Season the quail lightly with salt and pepper. Heat a little more oil in another frying pan and sauté the quail, skin-side down, over a medium heat until lightly coloured. Turn and sauté the other side for another 1–2 minutes, or until the quail are just cooked. Remove the quail from the pan, cut them in half and set aside.

When ready to assemble the terrine, melt the spiced butter gently, then stir in the thyme and keep in a warm place. Line a 30 cm cast-iron terrine mould with four layers of plastic wrap, leaving enough of an overhang to seal the finished terrine.

Arrange overlapping slices of pastirma across the base of the mould so the ends reach up the sides. Pack in enough chicken livers to cover the base and drizzle on about 4 tablespoons of the melted spiced butter. Place four pieces of quail along the length of the terrine, filling in the gaps with more chicken livers. Drizzle on another few tablespoons melted butter. Arrange the leeks on top of this layer of chicken livers, running them end-to-end to fit the mould, then flatten and press them slightly. Drizzle with a little more spiced butter. Continue to form more layers using the remaining quail and chicken livers, drizzling in spiced butter as you go.

Pour any remaining butter over the final layer of the terrine and fold up the plastic wrap to cover and seal. Cut out a piece of polystyrene (or a few thick pieces of cardboard) just smaller than the mould and fit it inside the terrine. Sit a 1 kg weight on the polystyrene (full cans will also do) and refrigerate for at least 6 hours.

After 6 hours remove the weights. When ready to serve, unwrap the terrine and invert it onto a serving plate, then cut into 2 cm thick slices.

SERVES 10–12

Circassian chicken

The origins of this slightly strange dish, one of the masterpieces of Ottoman cuisine, are unclear. Did the name come about as a kind of homage to the fair-complexioned Circassian lovelies that were brought from their homeland north-west of the Caucasus Mountains to the palace harem as concubines and wives to the sultans? Or is it because this dish uses fresh coriander, which is otherwise virtually unheard of in Turkish cooking but prevalent in the food of Circassia? Whatever the truth of the matter, for Westerners the best way to think of this dish is as a sort of pâté or spread to serve as a starter or as part of a mezze selection. Serve it with hot buttered Turkish bread, triangles of toasted flat bread or Lavosh Crackers and accompany with Pickled Cucumbers with Fennel.

60 ml walnut oil

2 teaspoons sweet paprika

120 g Strained Yoghurt

cup shredded coriander leaves

POACHED CHICKEN

1 large free-range chicken breast on the bone

1 small onion, cut into quarters

1 stick celery

1 sprig thyme

2 bay leaves

½ lemon

½ teaspoon white peppercorns

1 red bullet chilli, split lengthwise

WALNUT SAUCE

30 g unsalted butter

1 purple onion, finely diced

4 cloves garlic

2 teaspoons sweet paprika

½ teaspoon hot paprika

2 slices stale sourdough bread, crusts removed

chicken stock (reserved from the poached chicken)

150 g walnuts

1 teaspoon sea salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

squeeze of lemon juice

To poach the chicken, put the bird and all the aromatics into a large, heavy-based saucepan and cover with water. Bring to the boil, skimming away any fat and impurities that rise to the surface, then lower the heat immediately. Simmer very gently, covered, for 5 minutes. Turn off the heat and leave the chicken in the stock for 20 minutes.

Pull the chicken meat off the bone and shred it as finely as you can. Reserve for later. Strain the stock and reserve.

Meanwhile, heat the walnut oil and paprika in a small saucepan until just warm. Remove from the heat and leave to infuse for at least 30 minutes.

To make the walnut sauce, melt the butter in a heavy-based frying pan. Add the onion, garlic and both paprikas and sweat over a low heat for 10 minutes, until the onion is very soft.

Soak the bread in a little of the reserved chicken poaching stock. Squeeze it to remove as much moisture as possible and set aside.

Pulse the walnuts to fine crumbs in a food processor. Add the onion mixture and pulse to a smooth purée. Crumble in the bread, then add the salt, pepper and lemon juice and blend. With the motor running, trickle in enough of the reserved poaching stock to produce a mayonnaise consistency.

Tip the walnut sauce into a large bowl. Add the shredded chicken, strained yoghurt and coriander and stir well to combine. Taste and adjust the seasoning.

To serve, place scoops of the pâté onto each of four serving plates. Use the back of a teaspoon to make an indentation in the surface and drizzle in a little paprika oil.

SERVES 4

Braised chicken with green chillies, sucuk, turnips and leek ‘noodles’

Sucuk is a spicy Turkish sausauge and can be found in Turkish or Middle Eastern butchers and some specialist delis.

30 g unsalted butter

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

800 g boned free-range chicken thighs, cut into chunks

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

2 small turnips, peeled and cut into wedges

6 long green chillies, seeded and diced

1 large purple onion, cut into large dice

1 vine-ripened tomato, seeded and roughly chopped

1 clove garlic, sliced

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 bay leaf

100 g sucuk, sliced

250 ml leek poaching liquid (reserved from making the ‘noodles’)

squeeze of lemon juice

LEEK ‘NOODLES’

4 small leeks

750 ml Chicken Stock

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon lemon juice

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

Trim the tops of the leeks neatly and rinse well to get rid of any lingering dirt. Pour the stock into a baking tray and add the leeks, then poach for 20 minutes, or until just tender. Drain and reserve the poaching liquid. Allow the leeks to cool.

When the leeks are cool enough to handle, use a sharp knife to cut them in half lengthwise and then into long, fine shreds. Put the shredded leeks into a bowl, then add the oil and lemon juice and season with salt and pepper.

Meanwhile, heat the butter and oil in a heavy-based casserole dish. Season the chicken pieces lightly with salt and pepper and sauté over a medium heat until golden. Add the vegetables, paprika, bay leaf, sucuk and ¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, then stir briefly and add the leek poaching liquid. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat, cover and simmer for 10 minutes or until the turnips are cooked through.

When ready to serve, remove the pan from the heat and stir in the lemon juice, then taste and adjust the seasoning with salt and pepper, if necessary. Divide the braised chicken evenly between four warmed plates. Twirl the leek ‘noodles’ into little swirling mounds on top of the chicken and serve straight away.

SERVES 4

Claypot chicken with dates, sucuk and bulgur

In Turkish cookery there’s a distinctive group of dishes known as güveç, which take their name from the earthenware pot in which they are cooked – in the same way that the tagine does in Morocco. In rural Anatolia the cooking pots may be sealed and buried in the ashes of a fire to cook slowly overnight – or, only slightly less romantically, in the local baker’s oven. If you don’t have a clay pot, a heavy-based cast-iron casserole dish will serve almost as well.

Güveç dishes encompass all sorts of meat or poultry cooked with pulses, vegetables and fruits. My addition of star anise is not remotely Turkish, but it adds a wonderful layer of aniseed flavour. This güveç is spicy with a lingering sweetness, so serve it with a light salad or braised wild greens. A dollop of yoghurt would also be delicious.

Sucuk is a spicy Turkish sausauge and can be found in Turkish or Middle Eastern butchers and some specialist delis.

45 g unsalted butter

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

2 purple onions, cut into thick rings

1 clove garlic, sliced

2 long red peppers, seeded and cut into rings

2 long green peppers, seeded and cut into rings

2 long green chillies, seeded and diced

1 heaped teaspoon ground cumin

1 level teaspoon ground cinnamon

generous splash of sherry

2 large vine-ripened tomatoes, skinned, seeded and diced

50 g bulgur, washed

350 ml Chicken Stock

1 stick cinnamon

2 star anise

few sprigs thyme

2 × 400 g poussins

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon olive oil

50 g sucuk, sliced

4 medjool dates, seeded and cut into quarters

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Heat the butter and extra-virgin olive oil in a heavy-based casserole dish. Gently sweat the onions, garlic, peppers and chillies with the cumin and cinnamon for about 5 minutes, or until the vegetables soften. Add the sherry, tomatoes, bulgur, chicken stock, cinnamon, star anise and thyme and bring to the boil. Lower the heat, then cover and simmer gently for 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, cut the poussins into quarters and season lightly with salt and pepper.

In another heavy-based frying pan, heat the olive oil over a medium heat and brown the meat lightly all over. Add the sucuk and fry until golden brown on both sides. Transfer the poussins and sucuk to the casserole dish and tuck in the dates. Cover the pan and cook in the preheated oven for 20 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasoning and serve straight away.

SERVES 2

The Noah Vine

It may come as a surprise to learn that Turkey is the world’s fourth-largest producer of grapes. The bulk of Turkish vines produce eating grapes, with most crops going to fresh table grapes or dried sultanas and raisins. Others go towards the manufacture of raki, the national drink, but only a paltry three per cent of total production is used for wine-making.

Yet Turks are very keen to point out to visitors that their country was the birthplace of wine. The Bible tells us that after the flood, Noah planted a vineyard on the sunny slopes of Mount Ararat, becoming the world’s first recorded vigneron. And it wasn’t long before Noah became the world’s first recorded drunkard, with the discovery that fermented grapes produce a delicious-tasting beverage with several happy side-effects.

This Biblical story has recently been given greater weight by archaeological discoveries of wine-making paraphernalia in the region that date back to the Neolithic period. There has been other corroborating evidence of early wine-making in the nearby Zagros Mountains, in Titris Höyük in southeastern Turkey and in Hittite burial chambers near Ankara.

The discovery of these early artefacts has intensified the hunt for the ‘Noah Vine’ in Turkey’s Taurus Mountains. This elusive vine is generally regarded as the common ancestor for the many thousands of modern domesticated grape varieties in existence around the world today.

While Turkey may be the birthplace of wine, the country’s wine industry today can perhaps best be described as still being in its infancy. Although early inhabitants, such as the Greeks, Romans and Byzantines, had a strong tradition of wine-making, the arrival of Islam in the eighth and ninth centuries brought things to a halt. During the Ottomans’ 600-year reign, Muslim subjects were prohibited from drinking wine, although minority Christian communities of Greeks and Armenians still produced wine in very small quantities.

The modern Turkish wine industry owes its existence to Kemal Atatürk’s modernising drive and the removal of Islam as a state religion. As a result, the 1920s saw a boom in viticulture and many of Turkey’s oldest wine companies date back to this time. Over the course of the last eighty years or so, dozens of small wineries have sprung up around the country, although their contribution is relatively small. The large producers – Doluca, Kavaklidere and Kayra – are the biggest players, each with an annual production of more than 10,000,000 litres.

With its Mediterranean climate of cool wet winters and hot dry summers, Turkey certainly offers a perfect environment for growing wine. And with a population of seventy-five million, it would seem there is limitless potential to develop the industry. But the Turks do not seem to have taken to wine in a big way. It’s hard to pinpoint the reason why the domestic consumption of wine remains at less than one litre per capita per annum. It’s not because alcohol consumption and intoxication are frowned upon in what is a predominantly Muslim population – after all, most Turks seem perfectly happy to drink beer and raki in very healthy quantities.

One thing for sure is that the industry is not being helped by Turkey’s prohibitive taxes. The current government taxes home-produced wines at a whopping sixty-three per cent of the wholesale price, and has recently reduced import tariffs on European wines, allowing a flood of foreign wines to wash through the country. In the face of such obstacles, it is hardly surprising that many of the larger Turkish wine producers are now focussing their marketing efforts on more receptive overseas markets, such as Europe, North America and even Japan.

For a visitor to the country, though, there is something delightfully exotic and enticing about sampling new indigenous grape varieties, with names such as yapincak, sultaniye, bogazkere, okuzgozu and narince, to name but a few. And it’s even more exciting to think that with each sip you’re tasting a little piece of ancient history.

Chicken in pistachio, sumac and sesame crumbs

I like to serve this crunchy, moist and flavoursome chicken with Shepherd’s Salad, which provides another textural element via its combination of cucumber, peppers, radishes and tomatoes.

4 small free-range chicken breasts, skinned

2 free-range eggs

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

plain flour

80 ml olive oil

lemon wedges to serve

PISTACHIO CRUMBS

100 g fresh breadcrumbs

1 tablespoon ground sumac

finely grated zest of 1 lemon

60 g unsalted shelled pistachios, coarsely chopped

¼ cup sesame seeds

⅔ cup finely grated parmesan

To make the crumbs, put the breadcrumbs into a food processor with the sumac, zest and pistachios and pulse briefly – you don’t want to break up the nuts too much. Add the sesame seeds and parmesan and pulse briefly to combine.

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Lightly flatten the chicken breasts to an even 15 mm thickness.

When ready to cook the chicken, lightly beat the eggs with a little water in a shallow dish to make an egg wash. Set up a production line of seasoned flour, egg wash and crumb mix. First dip the chicken pieces into the flour, then the egg wash and finally the crumb mix, patting them carefully all over.

Heat the oil in a heavy-based frying pan and sauté the chicken pieces, two at a time, until golden brown all over – this should only take a few minutes. Transfer to a baking tray and cook for 8–10 minutes in the centre of the oven. Remove the chicken from the oven and allow to rest for a few minutes before serving with wedges of lemon.

SERVES 4

Roast chicken with pine nut and barberry pilav stuffing

1 × 1.5 kg free-range chicken

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil

250 ml Chicken Stock

watercress to garnish

PILAV STUFFING

280 g short-grain rice

600 ml Chicken Stock

55 g unsalted butter

1 large purple onion, finely diced

2 cloves garlic, finely diced

60 g pine nuts

½ teaspoon ground allspice

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

cup barberries

cup barberries

sea salt

squeeze of lemon juice

cup unsalted shelled pistachios, roughly chopped

cup unsalted shelled pistachios, roughly chopped

½ cup shredded flat-leaf parsley leaves

To make the stuffing, put the rice into a large bowl and rinse well under cold running water, working your fingers through it to loosen the starch. Drain off the milky water and repeat until the water runs clear. Cover the rice with cold water and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Drain the rice and rinse a final time, then drain again.

Bring the stock to the boil, then lower the heat and keep at a simmer.

Melt the butter in a heavy-based saucepan. Add the onion and garlic and sauté over a low–medium heat, stirring continuously, until the onion starts to soften. Add the pine nuts and spices, then increase the heat and sauté until the nuts start to colour. Add the barberries to the pan, followed by the simmering stock. Season with salt, then return to the boil, stir briefly, and cover with a tight-fitting lid. Cook over a very low heat for 15 minutes.

Tip the cooked rice onto a shallow tray and sprinkle on the lemon juice, pistachios and parsley. Use a fork to fluff up the grains and leave to cool.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 200°C. Clean the chicken, removing any excess fat from around the cavity. Stand the chicken upright and season lightly inside with salt and pepper. Spoon around half the stuffing into the cavity, being careful not to overfill it, and secure the skin at the opening with a small skewer. Set the remaining rice aside. Season the chicken lightly with salt and pepper and rub with oil, then transfer it to a heavy-based baking tray. Pour in half the stock and roast for 20 minutes. Lower the oven to 180°C and roast for a further 40 minutes. Remove the chicken from the oven and leave in a warm place for 10 minutes to rest.

While the chicken is resting, reheat the remaining stock and pilav in a saucepan over a gentle heat. Spoon out the stuffing from the chicken and add it to the pan. Mound the rice onto the centre of a warm serving platter. Cut the chicken into quarters, stack it around the rice and serve garnished with watercress.

SERVES 4

Skewered sweet-spiced duck

With its fatty skin, duck lends itself very well to fiercely hot grilling. It’s important to make sure that the skin is all facing the same way when you are skewering the meat, otherwise you’ll end up with a mix of crisp skin and burnt flesh. I like to serve this sweet duck with Spicy Kisir Salad.

4 duck breasts

1 heaped tablespoon Poultry Spice Mix

sea salt

warmed flat bread to serve

Trim the duck breasts of any excess skin and sinew. Slice each breast into four strips. Thread the duck strips onto long flat metal skewers, two strips per skewer, making sure the skin is all facing the same way. Pack the duck strips onto the skewer fairly tightly, so that the meat will cook brown and crisp on the outside but remain a little pink inside.

When ready to cook, heat a griddle or heavy-based frying pan over a high heat. Dust the kebabs lightly with the spice mix and cook for 2 minutes on each side – around 8 minutes in total. Season with salt while cooking.

Serve the duck kebabs on pieces of warmed flat bread and let everyone help themselves to salad.

SERVES 4

Duck döner kebab

This recipe is a playful interpretation of the ubiquitous döner kebab – spit-roasted layers of lamb that are sliced into warmed flat bread, topped with salad, rolled up and eaten as a filling snack-on-the-go all around the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. Try serving it with Soft Herb Salad.

1 large clove garlic

1 teaspoon sea salt

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon hot paprika

½ teaspoon ground allspice

½ teaspoon ground nutmeg

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

100 ml olive oil

4 duck legs, boned

4 long red chillies

2 vine-ripened tomatoes, sliced

1 quantity Soft Herb Salad to serve

warmed flat bread to serve

Crush the garlic with the salt, then combine in a bowl with the spices and 80 ml of the oil. Trim the duck of any excess fat and sinew, keeping each piece of meat whole, then toss gently in the marinade to coat. Leave overnight or for at least 2–3 hours to marinate.

When ready to cook, preheat the oven to 160°C. Heat a heavy-based baking tray on the stove top over a high heat, then add the remaining oil and sear the duck pieces, skin-side down, until coloured. Turn and sear the other side. Place a chilli on top of each duck leg, then transfer to the oven and cook for 30–40 minutes.

Remove the duck from the oven and transfer to a wire rack on a tray to catch the juices. Rest for 5–10 minutes. Meanwhile, add the tomatoes to the salad and toss gently. Slice each piece of duck leg very thinly and serve, drizzled with the juices, on pieces of warm flat bread with the roasted chillies. Let everyone help themselves to salad.

SERVES 4