The old two-storey stone houses painted in brilliant pinks, lilacs and yellows seemed to tumble joyously, one on top of the other, down towards the harbour.

The next morning was Sunday, and the memory of the previous night’s raki indulgence still lingered. Luckily the day had dawned bright and sunny, so a brisk reviving walk was in order. We climbed the narrow cobbled street behind Tara’s house to admire the view. From the peak of the hill we could see beneath us a jumble of twisting laneways and red-tiled rooftops. The old two-storey stone houses painted in brilliant pinks, lilacs and yellows seemed to tumble joyously, one on top of the other, down towards the harbour. In the distance, the bay of Ayvalik stretched out in a broad, lazy curve. The deep turquoise waters were dotted with little islands, basking like seals in the sunshine, and further away still, we could see the purple mountains of Lesbos rising out of the Aegean Sea.

Perched as we were on the edge of the Greek archipelago, with the reminder of Ayvalik’s own Greek heritage sprawled below us, it was strangely disconcerting to hear the muezzin’s prayer call start up from the nearby mosque. Since the sixteenth century Ayvalik had been predominantly a Christian town, and Greeks and Turks had co-existed perfectly happily on these peaceful shores, undisturbed by politics. It was only in the 1920s, in the aftermath of war, when the twin imperatives of nationalism and religion led to a series of population exchanges, that Greek Christian families vanished entirely from the region. Their hurriedly abandoned houses were soon occupied by bewildered Muslim families, themselves uprooted and ‘repatriated’ from nearby islands and other more distant parts of the Greek mainland.

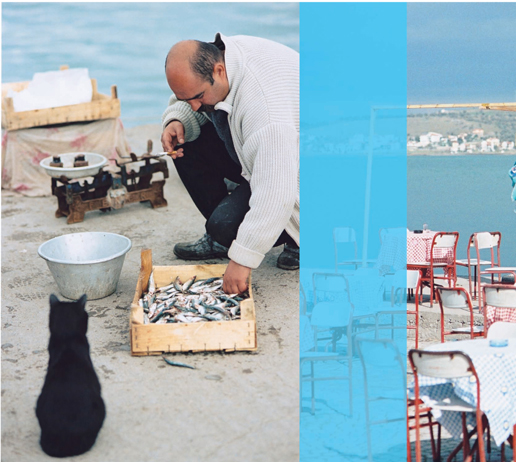

Down on the foreshore, the fishermen were busy making up for yesterday’s weather-enforced absence. We wandered along the quay past brightly painted wooden fishing boats, watching the catch being hauled ashore. There were buckets of red mullet, silvery dory and sea bass, some late-season anchovies, tiny papalina and a few large stingrays. Further on, we admired a pyramid of neatly stacked razor clams, each tidy bundle carefully wrapped in newspaper, ready for sale.

Our eyes were drawn to a huddle around two men in a tiny blue rowing boat. They were working their way through a crate of spiky black sea urchins; fascinated, we watched as one man used a pair of oversized scissors to crack them open, a little like slicing the top off a soft-boiled egg. His partner was carefully spooning out the brilliant orange corals and slipping them into small jars to sell to their waiting customers. Noticing our interest, a young man standing next to us explained in faltering English that the sea-urchin catch is highly protected, and restricted to Ayvalik, where the trade is passed down from father to son. The spiky black denizkestanesi are prised off the rocks using long, flexible lightweight poles and the professional fishermen are careful to collect only the largest, mature sea urchins.

By now the waterside cafés were filling up with Sunday strollers out enjoying the sunshine. Tara told us that in the hot summer months Ayvalik becomes a busy resort town, primarily visited by Turkish holiday-makers. It seems that European tourists tend to prefer the fleshpots of Bodrum and Marmaris further to the south.

Today we were doing as the locals, and heading for a day out on Cunda Island; also known as Alibey. This is the largest in the Ayvalik Islands group, sitting just a short ferryride offshore. In fact, it’s also connected to the mainland by a causeway and bridge, so we took the more expedient option of a bus ride, jammed in with the other day-trippers from Ayvalik. On the way out of town we passed a tatty-looking olive oil factory, quieter now, out of season, but Tara told us that after the harvest, when the factory is working at full steam, the pungent smell of olive oil hangs over the whole town like a heavy cloud.

Cunda Island had the sleepy feel of a resort town out of season. After weeks of cold weather, people seemed keen to make the most of the spring sunshine and all along the foreshore restaurants were setting up for a busy lunch trade. At Ada’s Restaurant, an eager waiter proudly pointed out the day’s fresh selection before seating us at a table in the dappled shade, right by the water’s edge.

The sea air had sharpened our appetites and we were ready to attack lunch. Our friendly waiter brought a plate of new season’s artichokes, braised in olive oil, and another of briny green samphire, redolent of the sea. Next, a feast of mussels: some stuffed in the shell with rice, others served as a cold tomatoey braise called pilaki, and finally, a platter of delectably crunchy fried mussels with a thick garlic dipping sauce. We munched contentedly in the warm sunshine, listening to the waves lapping gently at the quay. Between mouthfuls, Tara told us that Ada’s husband caught much of the restaurant’s fish himself, and she pointed him out, sitting on an upturned barrel mending his nets, cup of tea at his side.

Further along the harbour, dondurma and lokma sellers were vying for attention, and we felt duty-bound to give them both our custom. Luckily we had just enough room after our fish lunch to enjoy pistachio ice-cream in freshly made waffle cones and a little tub of syrup-soaked doughnuts, hot from the deep-frier.

Ready to explore more, we headed inland, away from the bustling waterfront, following a cobbled laneway that led us gently up the hill towards an old Greek Orthodox church. Long abandoned by its Christian congregation, it had fallen into a state of disrepair; its columns were crumbling and the stucco work was cracked and faded. As we turned the corner, the houses thinned out and the village quickly gave way to small fruit orchards and neat, densely planted allotments. Further away, the hillsides were covered with pine and olive trees and we could smell mint on the warm breeze.

Through an open gateway we spied a dainty white goat gazing curiously back at us. And then an elderly lady appeared, clutching in her arms a baby kid.

From behind a high stone wall we heard a quavering voice calling out, ‘Come my pretty daughters, come my little girls!’ and through an open gateway we spied a dainty white goat gazing curiously back at us. And then an elderly lady appeared, clutching in her arms a baby kid. She seemed surprised to see us, but invited us in to admire her brood.

Like many villagers, the old lady and her husband were largely self-sufficient. They grew their own wheat and vegetables, the goats provided milk, yoghurt and cheese, the chickens produced eggs. When the weather was good, her husband was still, God willing, sprightly enough to go out fishing; otherwise they made do with a largely vegetarian diet. We were charmed by her smile and willingness to share her life with us, complete strangers that we were. She seemed equally fascinated by us, and did her best to ply us with gifts of honey and freshly laid eggs. Following Tara’s example, we said our thanks and farewells in the traditional way, kissing the old lady’s hand and touching it to our foreheads. As she waved us goodbye, she smiled her sweet smile and asked us to come back and see her again.

Stuffed mussels, Istanbul street-style

For us, a defining image of Istanbul will always be the great trays of gleaming blue–black mussels that are sold from vendors around the street cafés, markets and waterfront. They were exquisitely displayed, the shells open just enough to reveal their stuffing of plump orange mussel, herbed rice, pine nuts and currants. Always willing to make the most of this bounty, we also learned the elegant art of eating these mussels: you break off the top shell, squeeze on a little lemon juice, then use the loose shell as a scoop to spoon the delicious contents straight into your mouth.

There’s also an art to opening live mussels, but it definitely gets easier with practice. Soaking the mussels in warm water first relaxes them, so that the shells open a little. You then insert a sharp knife between the shells along the flat edge and cut through the mussel where it is attached to the top, rounded end. The shells can then be prised open gently and filled with the traditional rice stuffing before cooking.

This is a great starter – for an extra-special presentation, lightly brush the shells with vegetable oil to give them a glossy sheen.

¼ cup currants

150 g short-grain rice

30 mussels, cleaned and bearded

80 ml olive oil

60 g pine nuts

1 large onion, finely diced

2 cloves garlic, finely chopped

¼ teaspoon ground nutmeg

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 vine-ripened tomato, grated

pinch of sea salt

boiling water

cup finely chopped dill

cup finely chopped dill

cup finely chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

cup finely chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

lemon wedges to serve

Soak the currants in a little warm water for 10–15 minutes, then drain.

Meanwhile, put the rice into a large bowl and rinse well under cold running water, working your fingers through it to loosen the starch. Drain off the milky water and repeat until the water runs clear. Cover the rice with cold water and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Drain the rice and rinse a final time.

Soak the cleaned mussels in a sink or large bowl of warm water for about 10 minutes.

Heat the oil in a saucepan. Fry the pine nuts, onion, garlic and spices on a medium– low heat for about 10 minutes until the pine nuts begin to colour a light golden brown. Stir in the drained rice, tomato and currants and cook for 2 minutes. Season lightly with salt, then pour on enough boiling water to just cover the rice. Stir, then bring to the boil and cover with a tight-fitting lid. Cook over a very low heat for 15 minutes, or until the liquid has been absorbed. Tip the rice into a shallow bowl, then fork through the herbs and leave to cool a little.

To prepare the mussels, use a small sharp knife and work over a large bowl to catch and reserve the juices. Hold each mussel by its narrow end, with the ‘pointed’ edge facing outwards. Insert the knife between the two shells near the large rounded top and cut through the mollusc where it is attached. You should then be able to prise the shells open, taking care not to break them – the idea is to open them slightly, not fully, and for the mussels to stay in their shells.

Strain the reserved mussel juice into a measuring jug and add water to make it up to about 500 ml if necessary, then tip this into a large, heavy-based saucepan. Stand a colander inside the pan. Spoon a generous amount of rice into each mussel, then squeeze the shells shut and wipe away any excess. Stack the mussels in the colander and cover with wet baking paper. Weight the mussels down with a plate to keep them from opening too wide as they cook. Cover the pan and bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for about 20 minutes.

Remove from the heat and let the mussels cool in the pan. When cold, refrigerate for at least 1 hour before serving chilled or at room temperature.

Stack the mussels onto a serving platter when ready to serve. To eat, break off the top shell, squeeze on a little lemon juice, then use the loose shell to scoop out the contents.

SERVES 4–6

Dill-battered mussels with red tarator sauce

All around Istanbul’s fish markets and along the quaysides of the Golden Horn and Bosphorus the air is filled with the intoxicating aroma of fried mussels and garlic. The mussels are often cooked on skewers in big metal drums full of spattering oil, and then served with a garlicky tarator sauce.

Tarators are thick sauces made from ground nuts, garlic and lemon juice or vinegar. Ranging from delicate to fiercely pungent, they are the definitive accompaniment to fried mussels and are also served with other fried or poached fish, and fried or steamed vegetables.

You’ll find red pepper paste in Middle Eastern food stores.

FRIED MUSSELS

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 small onion, peeled and roughly sliced

3 cloves garlic, smashed

1 stick celery, roughly chopped

1 red bullet chilli, split

30 mussels, cleaned and bearded

few sprigs thyme

1 bay leaf

100 ml white wine

vegetable oil for deep-frying

200 ml beer

cup self-raising flour

cup self-raising flour

pinch of bicarbonate of soda

1 tablespoon finely chopped dill

2 ice cubes

plain flour

lemon wedges to serve

RED TARATOR SAUCE

30 g stale white bread (crusts removed)

1 cup walnuts

1 clove garlic

1 teaspoon sea salt

2 tablespoons champagne vinegar

1 tablespoon hot Turkish red pepper paste

¼ teaspoon freshly ground white pepper

60 ml olive oil

To make the red tarator sauce, soak the bread in a little cold water for 5 minutes, then squeeze out the excess water. Pulse the walnuts in a food processor to fine crumbs. Crush the garlic with the salt, then add to the food processor with the bread, vinegar, pepper paste and pepper. Pulse to combine well. With the motor running, drizzle in the oil until the mixture comes together as a smooth sauce. Loosen the sauce with water until the consistency of pouring cream, then set it aside to let the flavours develop. It will thicken as it cools, and you may wish to thin it with a little more water.

To prepare the fried mussels, heat the olive oil in a large, heavy-based saucepan, then sauté the onion, garlic, celery and chilli for a few minutes until they soften. Add the mussels with the herbs and wine, then cover and bring to the boil. Cook on a high heat for about 4 minutes, shaking the pan from time to time, until the mussels open. Discard any that refuse to open.

Heat the vegetable oil in a large saucepan or deep fryer to 200°C. Whisk the beer, self-raising flour, bicarbonate of soda and dill to make a light batter. Add the ice cubes, which keep the batter cold and help make it really crisp. In batches of six, dust the mussels lightly with plain flour, then dip them into the batter and fry for 2–3 minutes, or until golden brown. Be careful as the oil will splutter and spit a lot. Using a slotted spoon, remove the mussels to drain on kitchen paper – keep them warm while you fry the remaining mussels. Serve piping hot with the tarator sauce and lemon wedges.

SERVES 4

Mussel pilaki

Pilaki are slow-braised dishes made with olive oil and tend to be served cold with plenty of crusty bread to mop up the rich sauce. This wonderfully garlicky mussel pilaki is one of our favourites. Make sure you use good tasty tomatoes.

36 mussels, cleaned and bearded

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 large onion, finely diced

6 cloves garlic, cut in half

1 carrot, scraped and cut into 1 cm dice

1 potato, peeled and cut into 1 cm dice

2 sticks celery, cut into 1 cm dice

1 large vine-ripened tomato, skinned and chopped

1 tablespoon tomato paste

250 Crab Stock, Chicken Stock or water

2 sprigs thyme

1 teaspoon sugar

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

juice of ½ lemon

2 tablespoons chopped dill

cup chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

cup chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

lemon wedges to serve

To prepare the mussels, soak them in a sink or large bowl of warm water for about 10 minutes, then drain. To open the mussels, use a small sharp knife and work over a large bowl to catch and reserve the juices. Hold each mussel by its narrow end, with the ‘pointed’ edge facing outwards. Insert the knife between the two shells near the large rounded top and cut through the mollusc where it is attached. You should then be able to prise the shells open and slip the mussel meat into another bowl. When you’ve opened all the shells, strain the collected juices and set aside.

Heat the oil in a heavy-based saucepan, then sauté the onion and garlic for 5–10 minutes, until soft. Add the carrot, potato, celery, tomato and tomato paste and sauté for a few more minutes, then stir in the reserved mussel juices, stock, thyme, sugar and pepper. Cook over a low heat for 20–25 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the vegetables are tender and the sauce is thick.

Stir the mussels into the sauce gently. Squeeze on the lemon juice and cook for around 4 minutes, then stir in the dill and half the parsley. Remove from the heat and leave to cool. When cold, refrigerate until ready to serve. Eat within the day as part of a mezze selection, sprinkled with the remaining parsley and served with lemon wedges.

SERVES 4

Fetta-and dill-stuffed sardines fried in chilli flour

Sardines are hugely popular in Turkey, eaten fried, stuffed, wrapped in vine leaves or grilled over charcoal. I always think that their oily texture and flavour needs to be subdued by strong accompanying flavours. Here I use salty fetta combined with chilli and herbs – it works a treat. Enjoy them as a starter with a glass or two of chilled raki.

8 sardines, filleted and butterflied

½ cup plain flour

¼ teaspoon sweet paprika

¼ teaspoon hot paprika

50 ml olive oil

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

FETTA AND DILL STUFFING

180 g fetta, crumbled

1 long red pepper, roasted, peeled, seeded and diced

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 teaspoon finely grated lemon zest

½ teaspoon dried mint

2 tablespoons finely chopped dill

2 tablespoons shredded mint leaves

1 small red bullet chilli, seeded and finely diced

To make the stuffing, combine all the ingredients in a bowl and mash with a fork to a smooth, homogeneous paste.

Open out the sardine fillets and lie them skin-side down on your work surface. Make a 2 cm long incision along the natural seam, cutting right through the skin. This will stop the fish from bursting open when you fry it. Smear a tablespoon of the stuffing along one side of the fish. Close the fish and squeeze gently to seal. Repeat with the remaining sardines.

Mix the flour and spices together. Heat the oil in a heavy-based frying pan. Season the sardines with salt and pepper, then dust them lightly with the seasoned flour. Fry the sardines, four at a time, over a medium heat for around a minute on each side, or until golden brown.

SERVES 4

Spicy fried calamari with whipped avocado, yoghurt and herb sauce

Everyone loves fried calamari and this light, tangy sauce makes a wonderful accompaniment for a special starter or mezze selection. It is a bit of work to make, but the resulting complex layering of flavours makes it well worth the effort.

You’ll find the red pepper paste used here in Middle Eastern food stores.

6 × 120 g whole calamari, cleaned

heaped ¼ cup cornflour

1 tablespoon fine polenta

1 tablespoon fine semolina ½ teaspoon ground turmeric

½ teaspoon ground coriander

½ teaspoon ground cumin

½ teaspoon ground ginger ½ teaspoon chilli powder

olive oil

AVOCADO, YOGHURT AND HERB SAUCE

50 ml olive oil

1 small onion, diced

1 small leek, white part only, diced

1 clove garlic, sliced

2 teaspoons ground cumin

1–2 tablespoons lime juice

1 vine-ripened tomato, skinned, seeded and chopped

2 teaspoons hot Turkish red pepper paste

½ cup mint leaves

1 cup flat-leaf parsley leaves

1 tablespoon water

180 g thick natural yoghurt

1 avocado, roughly chopped

To make the sauce, heat the oil in a heavy-based frying pan. Sauté the onion, leek, garlic and cumin over a low heat for 10 minutes until very soft. Add the lime juice, tomato and red pepper paste and stir briefly to combine. Tip into a vitamiser and blitz to a smooth purée, then scrape into a bowl.

Blitz the mint, parsley and water on high to a smooth purée. Add the yoghurt and avocado to the herb purée and blend until very smooth. Add the onion purée and blend until very smooth. Tip out into a bowl, then cover and refrigerate until needed.

Split the calamari tubes lengthwise, then trim the sides neatly and use a very sharp knife to score a fine diamond pattern on the inner surface. Reserve the tentacles.

Combine the cornflour, polenta, semolina and spices in a bowl, then stir well and sift into another bowl.

When you are ready to eat, heat a griddle or barbecue to its highest setting. Brush the calamari pieces and the tentacles with olive oil and dust lightly with the spice mix. Cook the tentacles on the searing hot griddle or barbecue for a few seconds, then add the remaining calamari, scored-side down. After about 30 seconds turn everything over. The scored calamari will curl into a tight cylinder. Cook for a further 30–40 seconds, then tip onto a warmed serving platter. Serve piping hot, accompanied by the sauce.

SERVES 6

Calamari stuffed with spicy eggplant pilav

An impressive but easy starter or mezze dish, these stuffed calamari are served warm here, but can also be refrigerated whole to be sliced and served cold later, making them perfect food for a party.

6 × 60 g cleaned calamari tubes

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil

6 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

extra-virgin olive oil to serve

lemon wedges to serve

SPICY EGGPLANT PILAV

1 small eggplant, cut into 1 cm dice

sea salt

1 tablespoon raisins, chopped

100 g short-grain rice

60 ml olive oil

1 small onion, finely chopped

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 red bullet chilli, split and seeded

½ teaspoon ground allspice

1 vine-ripened tomato, skinned and chopped

freshly ground black pepper

250 ml boiling water

1 tablespoon chopped dill

1 tablespoon chopped flat-leaf parsley leaves

To make the pilav, put the eggplant into a colander, sprinkle lightly with salt and leave for 20 minutes. Soak the raisins in a little warm water for 15 minutes. Rinse the eggplant and pat it dry. Drain the raisins.

Meanwhile, put the rice into a large bowl and rinse well under cold running water, working your fingers through it to loosen the starch. Drain off the milky water and repeat until the water runs clear. Cover the rice with cold water and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Drain the rice and rinse a final time.

Heat two-thirds of the oil in a heavy-based saucepan and gently sauté the eggplant until lightly coloured. Remove from the pan and set aside. Add the rest of the oil to the pan, then fry the onion, garlic, chilli and allspice until the vegetables soften. Return the eggplant to the pan with the tomato and raisins, then season with salt and pepper and stir gently.

Spoon the rice over the vegetables to form a layer (don’t stir it in!). This stops the eggplant breaking down into the rice. Carefully pour on the boiling water. Return the pan to the boil without stirring, then cover, reduce the heat and simmer for 15 minutes, or until the liquid has been absorbed. Remove the pan from the heat and slide a clean tea towel under the lid, then leave it to stand for a further 10 minutes. Tip the rice into a shallow bowl, fork through the herbs and leave to cool completely.

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Fill each squid tube with the cold pilav stuffing, making sure you work it right down to the bottom and that there are no air pockets. Leave about 1 cm at the open end and close with a toothpick. Season lightly with salt and pepper.

Heat half the oil in an ovenproof frying pan or small, heavy-based baking tray and sear the stuffed squid tubes over a medium–high heat, rolling them around like sausages until they are a nice golden colour all over. Add the garlic to the pan, then transfer to the oven and bake for 15 minutes. Remove the pan from the oven and leave the squid to cool for a moment on a wire rack.

To serve, slice each tube crosswise into four even pieces and arrange on a serving platter. Drizzle with a little extra-virgin olive oil and serve with lemon wedges.

SERVES 6

Prawns baked with haloumi in a claypot

Traditionally güveç dishes are cooked in little earthenware pots buried in the ashes of an open fire or barbecue. Different herbs are used depending on the region, and along the shores of the Mediterranean the wild basil that grows in profusion adds a lovely spicy note. You could also use dill, parsley or oregano with success. The combination of prawns and melted cheese makes this dish rather rich. It would make a light supper or lunch for four people, with a salad of bitter green leaves and plenty of crusty bread to mop up the sauce and melted cheese. You could also serve it as part of a mezze selection for eight people.

Pekmez, or grape molasses, is available from Turkish food stores.

8 raw king prawns, peeled (heads and tails removed)

40 g unsalted butter

1 small purple onion, diced

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 long red pepper, seeded and cut into 1 cm dice

1 long red chilli, seeded and shredded

1 teaspoon coriander seeds, roasted and lightly crushed

1 teaspoon caraway seeds, roasted and lightly crushed

pinch of saffron strands

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

few strips of lemon peel

sea salt

2 teaspoons pekmez

2 large vine-ripened tomatoes, skinned, seeded and chopped

¼ cup roughly torn basil leaves

extra-virgin olive oil

40 g haloumi, washed and finely grated

Preheat the oven to its highest setting. Use a sharp knife to butterfly the prawns and carefully pull away the intestines.

Melt the butter gently in a heavy-based frying pan. Add the onion, garlic, pepper, chilli, spices and peel and season lightly with salt. Sauté over a low heat for about 15 minutes, stirring frequently, until the vegetables are soft. Add the pekmez and cook for 5 minutes, then stir in the tomatoes and bring to a gentle boil. Gently add the prawns and basil to the sauce, then tip it all into a heavy-based casserole dish – or an earthenware pot if you have one. Sprinkle with extra-virgin olive oil, then scatter on the haloumi and bake in the oven for 3–5 minutes, or until the cheese is bubbling and brown.

SERVES 4

Marinated whiting with baby fennel braise

Marinating fish, whole or in portions, in olive oil, lemon and garlic is popular all around the Aegean and Mediterranean shores of Turkey. There are few things to beat this approach for simplicity and flavour, although do make sure you use spanking fresh fish.

In this recipe I’ve paired pan-fried fish with a braise of baby fennel, tomatoes and olives – the very essence of the Mediterranean. Adding snipped fennel fronds to the fish marinade imparts a hint of anise that complements the braise beautifully. Use other small fillets of fish, such as garfish, or even strips of salmon or prawns, if you like. For a dinner party you might like to cook a medley of different fish – just make sure they are all a similar size.

8 × 100–120 g whiting fillets

4 baby fennel, long stalks attached

30 ml olive oil

1 small purple onion, finely sliced

1 teaspoon ground cumin

¼ teaspoon hot paprika

10 kalamata olives, pitted and roughly chopped

1 vine-ripened tomato, skinned, seeded and diced

80 ml water

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

MARINADE

2 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon sea salt

finely grated zest of ½ lemon

2 tablespoons chopped fennel fronds

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

Combine the marinade ingredients in a shallow dish. Add the whiting fillets and turn in the marinade so they are evenly coated. Cover and refrigerate for 30 minutes, basting from time to time.

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Trim the ends of the fennel stalks neatly. Cut each bulb into quarters lengthwise. Heat the oil in an ovenproof frying pan or small, heavy-based baking tray. Add the fennel, onion, cumin and paprika and sauté over a medium heat for 3 minutes. Add the olives, tomato and water to the pan and season with salt and pepper. Transfer the pan to the oven and cook for 8–10 minutes or until the fennel is just tender. Return the pan to the stove top and cook on a high heat until the liquid has reduced and you have a thick braise.

Heat a heavy-based frying pan over a very high heat. Fry the fish, four pieces at a time, for a minute per side until lightly coloured. Serve immediately on top of the fennel braise.

SERVES 4

The Fish Doctor’s stew – with black pepper, lemon peel and mint

We ate several times at a wonderful seafood restaurant in Istanbul called Do a Balik. The chef–owner is nicknamed ‘The Fish Doctor’ for his knowledge of and skill in cooking seafood – as well as for his habit of wearing green surgeon’s scrubs! This is my interpretation of one of his wonderful dishes.

a Balik. The chef–owner is nicknamed ‘The Fish Doctor’ for his knowledge of and skill in cooking seafood – as well as for his habit of wearing green surgeon’s scrubs! This is my interpretation of one of his wonderful dishes.

The Fish Doctor’s stew included turbot and sea bass, which, sadly, are not readily available in Australia. Instead, choose a selection of baby snapper, John Dory, whiting or black bream. Cooking the fish on the bone adds incomparably to the flavour of the finished dish.

Serve with a plain rice pilav or boiled potatoes and a green salad.

2 × 400–500 g whole baby snapper, cleaned

2 × 300 g whole whiting, cleaned

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

50 ml extra-virgin olive oil

2 large onions, very finely diced

2 cloves garlic, very finely diced

½ teaspoon dried oregano

1 teaspoon dried mint

3 bay leaves

long piece of peel from 1 lemon

few sprigs thyme

½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

250 ml Chicken Stock

baby chives to serve

Preheat your oven to its highest temperature.

To prepare each snapper, cut away the head just below the gills. Snip off the side fins and cut the fish in half crosswise through the bone. To prepare each whiting, cut away the head, then cut the body into three pieces crosswise through the bone. Season well with salt and pepper.

Heat the oil gently in a heavy-based casserole dish. Add the onion and garlic and sweat very gently for a few minutes until they start to soften. Add the oregano, mint and bay leaves, peel and ½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, then cook over a low heat for another 5 minutes. Lie the pieces of fish on top of the onion mixture, then sprinkle on the thyme and red pepper flakes, add the stock and transfer to the very hot oven. Cook for 8 minutes, which should be long enough to colour the fish and just cook it through. Remove the pan from the oven, sprinkle with snipped baby chives and take to the table straight away.

SERVES 4

The Fish Doctor

One of the most interesting people we met in Istanbul was Ibrahim So ukda

ukda , also known as ‘The Fish Doctor’. Ibrahim Bey is the chef–owner of the city’s highly respected fish restaurant Do

, also known as ‘The Fish Doctor’. Ibrahim Bey is the chef–owner of the city’s highly respected fish restaurant Do a Balik, in Cihangir. Dubbed ‘The Fish Doctor’ because of his penchant for wearing surgeon’s scrubs, he is obsessed with seafood, a passion he dates back to his early childhood.

a Balik, in Cihangir. Dubbed ‘The Fish Doctor’ because of his penchant for wearing surgeon’s scrubs, he is obsessed with seafood, a passion he dates back to his early childhood.

We sat down to chat with The Fish Doctor in his sunny, rooftop restaurant, looking towards the Bosphorus in one direction, and across the Golden Horn to the Old City in the other. With his serious manner and immaculately coiffed silver-grey hair, it did feel a little like an appointment with one’s cardiothoracic surgeon! But in the late afternoon sunshine he relaxed and mellowed as he told us about some of his earliest memories of eating fish as a four-year-old child. To this day he greatly prefers it to meat.

The Fish Doctor began his working life selling fish at market and shortly afterwards, working from a tiny restaurant near the Eminönü waterfront, learning how to cook it. The catches in and around Istanbul are plentiful: there is turbot, bluefish, mackerel and hamsi – the local variety of anchovy – from the chilly waters of the nearby Black Sea. He soon decided that the best ways to prepare and cook this bounty were simple techniques, such as grilling or pan-frying, that allow the inherent flavour of the fish to shine through. He also began researching traditional recipes for seafood stews, or for stuffing whole fish with wild herbs before baking.

The more The Fish Doctor learnt about fish, the more he began to value its health-giving properties; over time, a new obsession arose, sparked again by childhood memories. He told us that the hillsides around Kastamonu, the Black Sea village where he grew up, are overrun with different types of wild greens, many specific to that region. In rural Turkey, especially in mountainous areas and along the Aegean coastline, wild greens form an important part of the local diet, but, for The Fish Doctor, gathering and eating this wild vegetation was a part of his childhood that had fallen away since moving to Istanbul.

A partnership between the bounty of the sea and the bounty of the hillsides seemed only natural to The Fish Doctor, and the name of his restaurant – do a, meaning nature, and balik, meaning fish – reflects this happy marriage. He started bringing in produce from the Black Sea and Aegean and now, on any given day, his restaurant will have around thirty different types of wild greens and herbs on offer as part of a vast selection of mezze. And on the several occasions we ate at Do

a, meaning nature, and balik, meaning fish – reflects this happy marriage. He started bringing in produce from the Black Sea and Aegean and now, on any given day, his restaurant will have around thirty different types of wild greens and herbs on offer as part of a vast selection of mezze. And on the several occasions we ate at Do a Balik we tried a fair few. Wild nettles, purslane, chicory and borage were some of the more familiar names we’d tasted, but others, such as feverfew, coltsfoot, knotweed and curledock, were like something from a medieval cookery book.

a Balik we tried a fair few. Wild nettles, purslane, chicory and borage were some of the more familiar names we’d tasted, but others, such as feverfew, coltsfoot, knotweed and curledock, were like something from a medieval cookery book.

Above the mezze display at Do a Balik, there is a chart of the different varieties of wild greens, outlining their various health-giving properties. Clearly they were working their magic on The Fish Doctor himself as the next day we learnt from one of the waiters that the tiny toddler we’d seen running around the restaurant tables was his eight-month-old son. Not bad going for a man of his advancing years!

a Balik, there is a chart of the different varieties of wild greens, outlining their various health-giving properties. Clearly they were working their magic on The Fish Doctor himself as the next day we learnt from one of the waiters that the tiny toddler we’d seen running around the restaurant tables was his eight-month-old son. Not bad going for a man of his advancing years!

Fried fish sandwich

Admittedly, tucking into fried fish sandwiches at home doesn’t have quite the same romance as eating them on the shores of the Bosphorus, but these are very tasty and would make a quick-and-easy weekend lunch.

30 ml olive oil

1 teaspoon sea salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½ teaspoon sweet paprika

4 × 120 g rock flathead fillets

1 baguette

extra-virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons good-quality mayonnaise (optional)

1 baby cos lettuce (inner leaves only), shredded

2 vine-ripened tomatoes, sliced

½ small purple onion, finely sliced into rings

½ cup mint leaves

2 pickled green chillies, shredded

generous squeeze of lemon juice

lemon wedges to serve

Heat the olive oil in a heavy-based frying pan. Combine the salt, pepper and paprika and sprinkle over the fish fillets. Fry the fish, about 2 minutes on each side, until crisp and golden brown.

Meanwhile, split the baguette lengthwise and brush inside with extra-virgin olive oil and add the mayonnaise, if using. Fill the baguette with lettuce, then top with the tomato, onion, mint and chilli. Place the hot fish on top and squeeze on the lemon juice. Press the baguette shut and use a very sharp, serrated knife to cut it into quarters. Serve wrapped in napkins with lemon wedges alongside.

SERVES 4

Roasted whole baby snapper with almond and sumac crumbs

Fish in Turkey is often served with nut tarator sauces, and I’ve included a couple of recipes for such sauces elsewhere in this book. For a change, this time I’ve turned the nuts into a crunchy coating for the fish.

Serve this dish hot from the oven with a salad or braised vegetables.

4 × 300 g whole baby snapper, cleaned

sea salt

freshly ground white pepper

80 ml extra-virgin olive oil

4 long red, yellow or green peppers

4 cloves garlic, peeled

1 large purple onion, cut into cubes

small handful of thyme sprigs

1 teaspoon dried oregano

ALMOND AND SUMAC CRUMBS

finely grated zest of 2 oranges

2 tablespoons olive oil

150 g blanched almonds

2 cloves garlic

½ cup homemade dried breadcrumbs

¼ cup sesame seeds

1 tablespoon ground sumac

To make the crumbs, leave the orange zest out on a plate to dry overnight or put it into a very low oven for 30 minutes. This will intensify the flavour.

Heat the olive oil in a heavy-based frying pan, then gently fry the almonds until golden brown. Remove and drain on kitchen paper. Add the garlic to the pan and fry gently until it just starts to colour, then remove from the pan to drain with the almonds. Fry the breadcrumbs, tossing, until just coloured. Tip all the fried ingredients into a vitamiser. Wipe out the pan to remove any remaining oil and toast the sesame seeds until just coloured, then add these to the vitamiser with the sumac and dried zest and blitz to form crumbs.

Preheat the oven to 160°C. To prepare each snapper, cut away the head just below the gills. Snip off the side fins and cut the fish in half crosswise through the bone. Season with salt and white pepper. Brush the fish pieces with half the olive oil and coat them with the crumbs.

In a bowl, tumble the peppers, garlic, onion and herbs with the remaining oil, so that everything is evenly coated, then tip into a heavy-based baking tray. Arrange the crumbed fish on top and roast for 25–30 minutes, or until the fish is just cooked.

SERVES 4