The goats, sheep and cows that graze in the nearby mountains produce the country’s sweetest milk, and the wild orchids that contain sahlep also grow abundantly in the mountain pastures.

Sedat had arranged for us to meet up with his friend Emine Serin in Kahramanmara , en route to our next destination, the south-eastern city of Gaziantep. Emine was a school teacher at a nearby town and she spoke English. ‘Em’s a free-spirit,’ Sedat had said, when we’d asked if she would be able to take time off school to be our translator and guide for the next five days. ‘She’ll be over the moon to have a break from school and an adventure with you.’

, en route to our next destination, the south-eastern city of Gaziantep. Emine was a school teacher at a nearby town and she spoke English. ‘Em’s a free-spirit,’ Sedat had said, when we’d asked if she would be able to take time off school to be our translator and guide for the next five days. ‘She’ll be over the moon to have a break from school and an adventure with you.’

Through a series of text messages we’d arranged to meet her in Yasar Pastanesi, a well-known pastry shop in the city centre. And over a cup of strong black tea and a plate of walnut baklava we began to get to know each other. Within a few minutes of our meeting, I could tell that Greg was smitten! Emine, a tall young woman with a lovely face and a gentle, eager manner, had taken the task of helping us with our food research seriously. She’d organised for us to meet the owner and chef at Mado restaurant, and we soon found ourselves sitting in a packed dining room on the outskirts of the city.

It was pitch-black and windy outside and we were eating, of all things, icecream. But this was not just any old ice-cream; it was dondurma, the famous Turkish ‘stretch’ ice-cream. We’d encountered something similar on our visits to Lebanon and Syria and had grown addicted to the smooth elastic texture and subtle flavour. Like its Middle Eastern cousin, dondurma is a pounded ice-cream and that unique stretchiness comes from mastic (plant resin) and sahlep (an extract of orchid root).

Talk to any Turk, and they’ll tell you that Mara is the true home of ice-cream. The goats, sheep and cows that graze in the nearby mountains produce the country’s sweetest milk, and the wild orchids that contain sahlep also grow abundantly in the mountain pastures. In fact, Mara

is the true home of ice-cream. The goats, sheep and cows that graze in the nearby mountains produce the country’s sweetest milk, and the wild orchids that contain sahlep also grow abundantly in the mountain pastures. In fact, Mara ¸ dondurma is more than just stretchy; the ice-cream we were tasting was firm enough to be eaten with a knife and fork and was perhaps better described as hard and chewy.

¸ dondurma is more than just stretchy; the ice-cream we were tasting was firm enough to be eaten with a knife and fork and was perhaps better described as hard and chewy.

Chef Osman Demiroz had just treated us to a whistle-stop tour of the gleaming Mado ice-cream factory, located behind the restaurant, which churns out around forty-five tonnes a week for transportation all around the country and even overseas. As well as the traditional mild-flavoured sahlep variety, Mado also makes a wide range of other flavours, including pistachio, almond, sour cherry, mulberry and blackberry, as well as bizarre flavours like pumpkin.

Of course, this ultra-modern factory product, impressive as it was, didn’t have quite the same romance as the handmade stuff. But during the long hot summer months, dondurma really comes into its own: local ice-creameries put on a show with traditionally garbed men wielding long hand-forged metal rods and working the ice-cream in a deep skinny barrel. Massive blocks of it hang out the front of shops, taffy-like from hooks, waiting to be sawn off with a sharp knife.

After we’d finished our ice-cream it was time to move on to our next destination – an hour further south, down near the Syrian border. By the time we reached Gaziantep it was almost midnight but the traffic was still chaotic, especially in the narrow streets near the bazaar, where our hotel was located. It turned out that Anadolu Evleri was just around the corner from one of Gaziantep’s most famous kebab restaurants, which was doing a roaring trade, even at that late hour.

Anadolu Evleri was a delightful boutique hotel, located down a winding alleyway and set behind a high stone wall. Owner Timur Schindel and his wife Dila had bought four old Anatolian houses in 2001 and renovated them to provide thirteen charming rooms – if slightly quirkily appointed. Mine was tucked in under the eaves at the top of the house; it had whitewashed walls, an antique brass bed and wooden beams set into the sloping ceiling.

I slept through the early prayer call the next morning, but was awakened instead by pigeons clucking and cooing outside my windows. We gathered for breakfast in a sunny dining room overlooking the central courtyard, or hayat. In the dappled morning sunshine we could better appreciate the light- and dark-patterned paving stones, the soft honey-coloured stonework and the graceful arched windows of the buildings. Timur explained that these features are typical of old Gaziantep houses, and it fascinated us how similar it was to the architecture we’d seen in Aleppo, over the border in neighbouring Syria.

It has to be said that Gaziantep – or Antep, as it’s generally called – gets pretty short shrift in the guide books. From a tourist perspective it’s not the most obviously appealing city. And yet Gaziantep dates back to Hittite times and it has a Roman citadel to explore. The city is located between Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean, at the intersection point of roads connecting the east to the south, north and west – and it was a key spot on the old Silk Road.

We’d heard that Antep food is a wonderful blend of Arabic, Armenian, Kurdish and Anatolian influences, and we were keen to start exploring the nearby markets. First, though, we had an appointment next door, at Imam Ça da

da .

.

We met with Burhan Ça da

da in his large airy restaurant, the fourth-generation owner of the business. It was late morning and the place was already filling up with families, groups of women and young couples. A few seemed to be tucking in to an early lunch, but most were swooning over plates of delectable pastries. It was these pastries we’d come to investigate, because, as well as being renowned for kebabs,

in his large airy restaurant, the fourth-generation owner of the business. It was late morning and the place was already filling up with families, groups of women and young couples. A few seemed to be tucking in to an early lunch, but most were swooning over plates of delectable pastries. It was these pastries we’d come to investigate, because, as well as being renowned for kebabs,  mam Ça

mam Ça da

da is famous in Turkey for its exquisite baklava.

is famous in Turkey for its exquisite baklava.

Antep baklava is made almost exclusively from pistachios, yet another thing the city is famous for, and it even lends its name to the nut – Antep fisti i. Burhan brought over a small wooden bucket of pistachios for us to inspect. They were a vivid emerald green and much larger than any we’d seen before. ‘These pistachios are of exceptional quality,’ said Burhan, doling out handfuls of the nuts for us to taste. ‘With ordinary pistachios, you get maybe 500–600 to a kilogram. The pistachios from Antep, there can be 130–200 to a kilogram.’

i. Burhan brought over a small wooden bucket of pistachios for us to inspect. They were a vivid emerald green and much larger than any we’d seen before. ‘These pistachios are of exceptional quality,’ said Burhan, doling out handfuls of the nuts for us to taste. ‘With ordinary pistachios, you get maybe 500–600 to a kilogram. The pistachios from Antep, there can be 130–200 to a kilogram.’

We nibbled at the pistachios delicately, aware that in Australia they are almost as costly as the emeralds they resembled. ‘Eat, my friends, eat!’ urged Burhan, trickling more nuts into our hands and chuckling at our expressions. Suddenly he leapt to his feet. ‘Come!’ he instructed, marching across the cool marble floor of the restaurant to a lift tucked away next to the busy kitchen.

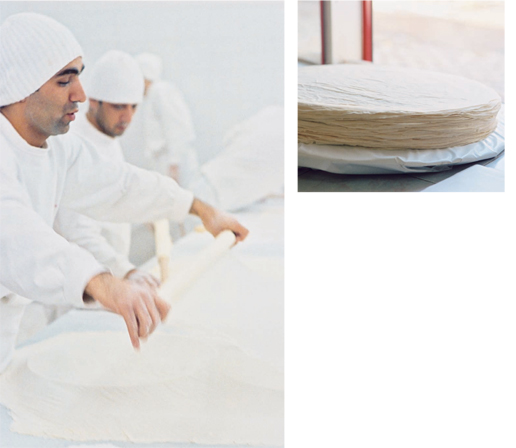

Up on the third floor, above the restaurant’s dining rooms, we walked into an extraordinary scene. Half the vast space was enclosed behind glass, where, in a cloud of fine white dust, a team of young men worked around a massive, long table. Using long wooden rolling pins called oklava, they rolled out stacked sheets of yufka pastry into ever-thinner layers. As graceful as ballet dancers, the yufka rollers rose onto their toes, then, arms fully extended, sank down onto the pastry, pushing and stretching it out in front of them. The effect was delicate, rhythmic and mesmerising – a sequence of rolling and lifting – the pastry itself, billowing in the air, as light as gossamer.

As graceful as ballet dancers, the yufka rollers rose onto their toes, then, arms fully extended, sank down onto the pastry, pushing and stretching it out in front of them.

Burhan smiled and continued, proudly, ‘This work is very skilled. The boys, they start here as young as seven or eight years old to learn how to become a yufka chef. It takes many years, but if they make it, it is a job that earns them respect … and they will have it for life.’

In the room next door, more men were busy assembling the large trays of pastries for baking. Some were draping the tins with layers of translucent pastry; others were scattering great handfuls of ground pistachios before gently settling on the top layers. Little boys, whose job it was to carry the trays of prepared baklava to the massive wood-fired oven, scuttled around the perimeter of the room.

We moved over to watch two men supervise the baking process. They were also specialists, knowing exactly where in the oven to place the trays and for how long, pushing them around on the end of long paddles and then whisking them out at just the precise moment.

Next, the trays of baked baklava were moved along a mini assembly line of gas rings. Each tray was spun around on the flame to maintain the temperature, before being flung onto the workbench where an elderly man ladled boiling sugar syrup onto the still-hot pans. We could see the top layers of golden pastry ‘dancing’, as the syrup bubbled up from the sides of the tin.

Burhan introduced us to the syrup-ladler – his father. Although well in his sixties, Talat Ça da

da came into the workshop every day, as he’d done all his life. Burhan told us that his father no longer works as a yufka chef, but oversees the final part of the process. As we watched Talat Ça

came into the workshop every day, as he’d done all his life. Burhan told us that his father no longer works as a yufka chef, but oversees the final part of the process. As we watched Talat Ça da

da lift the ladles of boiling syrup we could see that the knuckles on his hands were swollen, his fingers gnarled and distorted by the relentless, repetitive work. As is so often the case, beauty is achieved only at a cost. In the same way that ballet dancers’ feet are destroyed by their art, it seemed that the dance of the yufka rollers exacted its own terrible price.

lift the ladles of boiling syrup we could see that the knuckles on his hands were swollen, his fingers gnarled and distorted by the relentless, repetitive work. As is so often the case, beauty is achieved only at a cost. In the same way that ballet dancers’ feet are destroyed by their art, it seemed that the dance of the yufka rollers exacted its own terrible price.

Flower of Malatya

This is a bit of a play on one of my signature desserts, the Rose of Damascus. One of the wonderfully generous people we met on our Turkish travels was Emine Serin, a school teacher living in Malatya, the apricot capital of Turkey. This dish was created for her.

To form the pastry ‘petals’, you’ll need to find a teardrop-shaped pastry cutter, which are readily available from specialist food stores. They come in various sizes, and I like to use one about 12 cm long. You’ll also need a round pastry cutter that is about the same size as the ‘base’ of the tear drop.

Amardine sheets are essentially dried apricot paste and are available from Middle Eastern and Mediterranean food stores. Pekmez, or grape molasses, is available from Turkish food stores.

unsalted shelled pistachios, slivered

8 dried apricots, cut into ½ cm dice and rolled in icing sugar

handful of citrus blossoms (optional)

pekmez to garnish

APRICOT ICE-CREAM

400 ml water

250 ml sherry

4 cardamom pods, seeds only

500 g amardine sheets

200 g caster sugar

50 g mild honey

8 free-range egg yolks

600 ml thickened cream

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

100 g Candied Walnuts, crushed

FILO-PASTRY PETALS

10 sheets filo pastry

200 g clarified unsalted butter, melted

100 g icing sugar

100 ml mild honey, warmed

To make the ice-cream, combine half the water with the sherry and cardamom seeds in a heavy-based saucepan. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat. Add the amardine sheets and simmer gently, stirring occasionally, until they dissolve into a thickish, smooth consistency. Remove from the heat and allow to cool.

Gently heat the rest of the water with the sugar and the honey, stirring occasionally until the sugar has dissolved. When the syrup is clear, increase the heat and bring to a rolling boil.

Meanwhile, whisk the egg yolks in an electric mixer until thick, pale and creamy. With the motor running, slowly pour the hot sugar syrup onto the egg yolks. Continue whisking for about 5 minutes, or until the mixture cools. You will see it bulk up dramatically into a soft, puffy mass. Fold in the cream and vanilla extract and chill the mixture in the refrigerator.

Fold the amardine purée into the chilled ice-cream base, then pour into an ice-cream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When nearly set, add the walnuts, mix well and pour into two 26 x 22 cm (no more than 2 cm deep) trays lined with plastic wrap. Transfer to the freezer until ready to assemble the dessert.

To prepare the filo pastry petals, preheat the oven to 160ºC. Line and butter two baking sheets. Put a piece of filo on your work surface and brush it liberally with clarified butter and dust with icing sugar. Repeat with two more layers, drizzling half the warm honey instead of the icing sugar on the third filo sheet. Stack, brush and dust another layer, then repeat with a fifth and final layer, but do not dust with icing sugar. Repeat this process with the remaining five sheets of filo pastry. You should now have two stacks of filo pastry, each comprising five layers.

Use a 12 cm teardrop-shaped pastry cutter to cut nine petals from each pastry stack – 18 in total. Carefully transfer the pastry petals to the prepared baking sheets and cover with baking paper. Put another tray on top to weigh down the flowers and keep them flat as they cook. Bake for 8–10 minutes, or until golden. Remove from the oven and leave to cool.

When ready to assemble, remove the icecream from the freezer and turn out onto a chopping board, then peel away the plastic wrap. Use a pastry cutter to cut out 12 icecream rounds.

To serve, place a pastry petal in the centre of each plate so that it points upwards, and top it with ice-cream, aligning the curved edges. Add another pastry petal so that it overlaps the first slightly but tends to the left. Add another ice-cream round and finish with another petal, tending further to the left. Serve sprinkled with the slivered pistachios, the apricot pieces and orange blossom and drizzle with a little pekmez.

MAKES 6

Chewy Turkish ice-cream

This is our version of the famous ‘chewy’ Turkish ice-cream using sahlab, which comes from the root of a wild orchid that grows in the mountains of central Anatolia, and mastic, acacia tree resin. Both contribute to the thick chewy texture and the unique flavour. Pure sahlab is almost impossible to find, but you may well find powdered sahlab (for making hot milky drinks) in Middle Eastern stores. You won’t be able to replicate the distinctive stretchiness completely, but using the powdered form will go some way towards achieving it.

950 ml full-cream milk

300 ml pure cream

1 large grain mastic

225 g caster sugar

heaped ¼ cup sahlab powder or 1 teaspoon pure sahlab

long strip of peel from 1 orange

long strip of peel from 1 lemon

Put the milk and cream into a large heavy-based saucepan.

In a mortar, grind the mastic with a pinch of the sugar, then add the sahlab. Stir in about 200 ml of the milk mixture to dissolve the powders, then stir this into the saucepan with the rest of the milk mixture and the remaining sugar. Add the citrus peels and bring gently to the boil, then lower the heat. Simmer for 10–15 minutes, whisking continuously to stop the mixture catching and burning on the bottom of the pan. It will thicken to the consistency of a light pouring cream.

Pour the mixture into a bowl and press a sheet of greaseproof paper, cut to size, down onto the surface to prevent a skin from forming. When cold, tip into an ice-cream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MAKES 800 ml

Pistachio halva ice-cream

As well as being the sand-coloured, sesame-based confectionery with which Westerners are familiar, halva is also a type of Turkish dessert made from semolina or flour. Turkish confectioners often have displays of huge blocks of halva – many studded with nuggets of emerald-green pistachios. Because it is not too sweet, it works brilliantly in ice-cream.

250 ml full-cream milk

250 ml thickened cream

1 vanilla pod, split

long piece of peel from 1 lemon

100 g caster sugar

5 free-range egg yolks

70 g pistachio halva

25 g unsalted shelled pistachios

Put the milk, cream, vanilla pod and peel into a large, heavy-based saucepan and heat gently. Meanwhile, whisk the sugar and egg yolks by hand in a large bowl until thick and pale. Pour on the hot cream and whisk in quickly. Pour the mixture back into the rinsed-out pan and cook gently until it thickens to a custard consistency. You should be able to draw a distinct line through the custard on the back of a spoon. Remove from the heat immediately and cool in a sink of iced water. Stir from time to time to help the custard cool down quickly. Remove the vanilla pod and peel. Refrigerate the custard until chilled.

Pour the chilled custard into an icecream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

While the ice-cream is churning, crush the halva in a mortar to even crumbs. Blitz the pistachios in a food processor to form coarse crumbs. When the ice-cream is nearly churned, add the halva and pistachio crumbs and churn in briefly.

MAKES 600 ml

Yoghurt and honey sorbet

This is a silky, smooth sorbet with a light tang and subtle sweetness. It makes a wonderfully refreshing end to a rich meal. Serve it drizzled with a little more honey, or with a salad of fresh berries or stone fruits.

350 ml water

225 g caster sugar

1 tablespoon liquid glucose

250 g thick natural yoghurt

80 ml créme fraîche

60 ml pure cream

2 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons lime juice

In a small saucepan, gently heat the water, sugar and liquid glucose until the sugar has dissolved. Increase the heat and bring to a gentle boil. Simmer for 3 minutes, then remove from the heat and leave to cool. When cool, refrigerate until chilled.

Whisk together the yoghurt, créme fraîche and cream, then chill. Stir the honey and lime juice into the cold syrup, then stir this into the chilled yoghurt mixture. Tip into an ice-cream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MAKES 500 ml

[Clockwise from left] Pistachio Halva Ice-cream, Pomegranate and Vodka Sorbet, Yoghurt and Honey Sorbet

Pomegranate and vodka sorbet

Serve this very adult sorbet in cocktail glasses with an extra splash of icy cold vodka.

250 ml water

250 g caster sugar

80 g liquid glucose

400 ml pomegranate

juice (around 4 large pomegranates)

100 ml vodka

juice of 1 lime

Combine the water, sugar and liquid glucose in a heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring occasionally, until the sugar dissolves. When the syrup is clear, increase the heat and bring to the boil. Simmer for 5 minutes, then remove from the heat and leave to cool.

Stir in the pomegranate juice, vodka and lime juice. Pour into an ice-cream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MAKES 600 ml

Sour-cherry sorbet

225 ml water

70 g liquid glucose

270 g caster sugar

120 g dried sour cherries

350 ml blood orange juice

juice of up to 1 lemon

Combine the water, liquid glucose and 200 g of the sugar in a heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring occasionally, until the sugar dissolves. When the syrup is clear, increase the heat and bring to the boil. Simmer for 5 minutes, then remove from the heat and leave to cool.

Put the cherries into a heavy-based saucepan with the orange juice and remaining sugar. Heat gently until the sugar dissolves, then simmer for around 5 minutes, or until the cherries are soft. Remove from the heat and leave to cool.

Add the cold syrup to the cold cherry mixture and stir in 2 tablespoons lemon juice, then blend to a smooth purée in a vitamiser. Strain through a fine sieve, then pour into an ice-cream machine and churn according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Towards the end of the churning time, taste the sorbet and add a little more lemon juice to taste if required.

MAKES 600 ml

Milk pudding with labne, apricot and Turkish fairy floss

This is the classic milk pudding recipe, which I’ve tweaked by adding strained yoghurt to give it a lovely tang.

Turkish or Persian fairy floss is the super-sophisticated cousin of the familiar fairground sugary confection. You’ll find it in a range of different flavours in Middle Eastern food stores and some upmarket delis. As well as looking spectacular, its delicate texture and melting sweetness are irresistible to young and old alike.

4 grains mastic

120 g caster sugar

cup cornflour

cup cornflour

1 litre full-cream milk

long strip of peel from ½ lemon

long strip of peel from ½ orange

30 ml orange-blossom water

200 g Strained Yoghurt

orange-flavoured Turkish or Persian fairy floss to garnish

APRICOT PURÉE

300 g amardine sheets

150 ml water

70g caster sugar

1 tablespoon lemon juice

Grind the mastic with ½ teaspoon of the sugar in a mortar, then mix with the remaining sugar and cornflour in a bowl. Stir in 100 ml of the milk to make a paste.

Put the rest of the milk into a large, heavy-based saucepan, then whisk in the paste until smooth. Add the citrus peels and bring to the boil, whisking continuously, then lower the heat. Simmer for 4–5 minutes, whisking continuously to make sure it doesn’t catch and burn.

Remove from the heat, then strain into a bowl and cool in a sink of iced water, whisking continuously so that the mixture becomes light and fluffy. When the mixture cools to blood temperature, stir in the orange-blossom water, then fold in the strained yoghurt. Spoon into serving glasses and refrigerate until chilled.

To make the apricot purée, put the amardine, water and sugar into a heavy-based saucepan and cook gently, stirring occasionally, until the amardine softens and dissolves to a thickish, smooth consistency. Tip into a vitamiser and whiz to a smooth purée. For an even smoother consistency, pass the purée through a fine sieve, if you like. Stir in the lemon juice.

Spoon a little of the purée onto the milk puddings and keep chilled until ready to eat. Serve garnished with a top-knot of fairy floss.

SERVES 8

Toasted almond cream mousse

This soft and airy mousse was inspired in part by ke kül, a delicately flavoured milk pudding we tasted in Istanbul. It is delicious served on its own as a dessert – perhaps with cold poached pears – or as an accompaniment to Sticky Dried Fig Puddings, with the Fairy Chimneys or even with a piece of Walnut and Semolina Cake.

kül, a delicately flavoured milk pudding we tasted in Istanbul. It is delicious served on its own as a dessert – perhaps with cold poached pears – or as an accompaniment to Sticky Dried Fig Puddings, with the Fairy Chimneys or even with a piece of Walnut and Semolina Cake.

200 g blanched almonds, dry roasted

400 ml thickened cream

milk

1 stick cinnamon

3 free-range egg yolks

75 g caster sugar

2 x 1.6 g sheets leaf gelatine (gold)

2 free-range egg whites

Put the almonds into a heavy-based saucepan with the cream, 100 ml milk and the cinnamon stick and simmer over a very low heat for 30 minutes to infuse. Remove the pan from the heat and leave to cool. Remove and discard the cinnamon stick.

Blitz the cooled almond cream mixture in a vitamiser until very smooth. Pour the mixture through a fine sieve and discard the almond meal. Pour the almond cream into a measuring jug and add enough milk up to make it up to 500 ml. Pour this liquid into a saucepan and heat to a gentle simmer.

Meanwhile, whisk the egg yolks with the sugar in a large bowl. Pour on the hot almond cream and whisk to combine. Pour the mixture back into the rinsed-out pan and cook gently for about 5 minutes until it thickens to a custard consistency, stirring continuously so that the mixture doesn’t catch and burn. You should be able to draw a distinct line through the custard on the back of a spoon. Remove from the heat immediately and cool for a couple of minutes in a sink of iced water.

Soak the gelatine in a little cold water, then squeeze to remove any excess liquid. Add the gelatine to the warm custard and stir until dissolved. Leave the custard to cool, then strain through a fine sieve into a large bowl.

Whip the egg whites to soft peaks and fold them into the cold custard. Tip into a serving bowl and refrigerate until ready to eat.

SERVES 6

Thick fig cream dessert

We ate several meals at the amazing Ciya restaurant on the Asian side of Istanbul. One evening chef-owner Musa Da deviren served us a bewildering succession of traditional Anatolian ‘peasant’ dishes, culminating in an extraordinary dessert made from fermented fig seeds and cultured cream. It was rich and creamy and the fermented seeds tasted almost brandied. This is our attempt at recreating the spirit of the dish. Serve it in a pretty glass bowl so that everyone can help themselves, and accompany it with sponge fingers, wafer biscuits or perhaps a simple dish of caramel oranges.

deviren served us a bewildering succession of traditional Anatolian ‘peasant’ dishes, culminating in an extraordinary dessert made from fermented fig seeds and cultured cream. It was rich and creamy and the fermented seeds tasted almost brandied. This is our attempt at recreating the spirit of the dish. Serve it in a pretty glass bowl so that everyone can help themselves, and accompany it with sponge fingers, wafer biscuits or perhaps a simple dish of caramel oranges.

150 g dried figs, roughly chopped

cup caster sugar

cup caster sugar

2 tablespoons water

2 tablespoons Pedro Ximenez sherry or muscat

500 ml pure cream

1 stick cinnamon

½ vanilla pod, split

5 free-range egg yolks

Put the figs into a heavy-based saucepan with 3 tablespoons of the sugar, the water and the sherry. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer gently for about 15 minutes, or until the figs break down. Allow to cool a little, then whiz to a smooth purée in a vitamiser. Pour through a sieve to remove any chunks, but don’t worry about trying to remove the seeds. Set aside.

Put the cream into a heavy-based saucepan, then add the cinnamon stick and scrape in the vanilla seeds before adding the pod. Bring to the boil slowly, then remove from the heat and leave to cool slightly.

Whisk the egg yolks with the remaining sugar. Strain the hot cream onto the egg mixture, stirring continuously. Pour the mixture back into the rinsed-out pan and cook gently until it thickens to a custard consistency. You should be able to draw a distinct line through the custard on the back of a spoon. Remove the cinnamon stick and vanilla pod, then pour into a serving bowl and refrigerate until chilled.

Swirl the fig purée into the chilled custard, then refrigerate again until the custard thickens and sets firm.

SERVES 6

Pudding shops

The milk pudding is a much-loved category of dessert in Turkey. There is an entire profession of muhallebici – specialist milk-pudding makers – and pudding shops, devoted entirely to these dairy delights, are found in just about every Turkish town.

To those of us who grew up with a horror of insipid milky blancmanges and lumpy rice puddings, this passion might seem a bit bizarre. But milk puddings have been popular in the Middle East for centuries – they are one of the simplest desserts to prepare at home, and nearly every housewife will know how to knock up a muhallebi (the classic milk pudding) or sütlaç (rice pudding).

Turkish milk puddings come in myriad flavours and textures and in the windows and chill cabinets of even the most humble pudding shop you’ll find row upon row of tiny bowls to tempt you. This is also where you’ll find the thick rolled logs of Turkish clotted cream known as kaymak. Kaymak is thick enough to be cut with a knife and is used as a filling for all kinds of sweet syrupy pastries, poached apricots, or even spread onto bread with honey or jam, for a calorific breakfast treat.

When it comes to puddings, the simplest muhallebi is nothing more complicated than full-cream milk thickened with cornflour, ground rice or rice flour. Professional pudding makers use sübye, a milky pulp made from soaked, puréed rice, which helps to set puddings with a silky-smooth texture. Some muhallebi are flavoured with flower waters, orange zest, vanilla or mastic, others are thickened with ground nuts instead of rice.

Sütlaç, on the other hand, is closer to what we know as rice pudding. Some versions are enriched with eggs and baked in the oven, developing a distinctive burnt surface, a little like a créme brûlée. Zerde, a saffrontinted rice pudding with currants and nuts, is traditionally served at weddings and circumcision feasts. Kesme bulamaci is a pudding from the south-east of Anatolia, made using bulgur wheat instead of rice. One particularly esoteric pudding, tavuk gö sü, is made from finely shredded chicken breast. It comes as no surprise to learn that this particularly crazy-sounding dessert was the creation of the Ottoman palace kitchens.

sü, is made from finely shredded chicken breast. It comes as no surprise to learn that this particularly crazy-sounding dessert was the creation of the Ottoman palace kitchens.

One thing that all Turkish milk puddings share is a creamy lightness of texture and a subtlety of flavour that is particularly welcome during the long hot summer months. Once you’ve tasted them, it’s hard to get the memory out your mind.

Caramelised rice pudding

Another pudding-shop favourite, little take-away glass or earthenware bowls of chilled rice pudding are popular all around the eastern Mediterranean. Some are exotically flavoured with mastic, others with saffron or rosewater. Some have currants, pine nuts or pistachios lurking in their creamy depths, and some are served with the top browned under the griller to form a dark, burnt layer. My own version is rich and creamy, but the sweetness comes from macerated raisins and a crunchy brûlée topping rather than the pudding itself.

200 g short-grain rice

100 g raisins

170 g caster sugar

30 ml sherry

150 ml water

500 ml full-cream milk

250 ml thickened cream

½ vanilla pod, split

1 stick cinnamon

60 g unsalted butter

4 free-range egg yolks

additional caster sugar

Put the rice into a large bowl and rinse well under cold running water, working your fingers through it to loosen the starch. Drain off the milky water and repeat until the water runs clear. Cover the rice with cold water and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Drain the rice and rinse a final time.

Put the raisins into a small saucepan with 2 tablespoons of the sugar, the sherry and the water. Heat gently to dissolve the sugar, then bring to the boil. Remove the pan from the heat and leave the raisins to macerate for 20 minutes or so. Strain and set aside.

Meanwhile, put the rice, milk, cream, vanilla pod and cinnamon stick into a large, heavy-based saucepan. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer gently for 10–15 minutes, until the mixture becomes thick and creamy. Stir occasionally to prevent it catching and burning on the bottom of the pan. Remove from the heat and set aside.

Cream the butter and remaining sugar in an electric mixer until thick and pale. Beat in the egg yolks one at a time until thoroughly combined. With the motor on low, slowly pour the hot rice onto the egg mixture and continue beating for 2–3 minutes, then briefly mix in the raisins. Allow to cool, then remove the vanilla pod and cinnamon stick.

Spoon into small bowls or ramekin dishes and refrigerate until chilled.

When ready to serve, sprinkle the surface of each pudding with a thin, even layer of caster sugar. Caramelise the surface with a small kitchen blowtorch until the sugar melts to a shiny glaze. (If you don’t have a blowtorch, preheat an overhead griller to its highest setting. Place the puddings on a baking sheet and slide under the griller, about 5 cm from the heat. Watch carefully to make sure they don’t burn.) Allow the topping to cool for 5 minutes before serving so that it hardens to a crisp toffee.

SERVES 8–10

Turkish coffee creams

If you enjoy cardamom-scented Turkish coffee, then you’ll love these indulgent creamy petit pots.

60 g dark-roasted, plain Turkish coffee, finely ground

4 cardamom pods, lightly crushed

1 stick cinnamon

250 ml pure cream

50 g best-quality dark chocolate, grated

5 free-range egg yolks

heaped ¼ cup caster sugar

Moisten the coffee grounds with a little water and put onto a muslin square with the cardamom pods and cinnamon stick, then tie securely with kitchen string to make a bag. Put the cream into a heavy-based saucepan with the muslin bag and bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 5 minutes. Turn off the heat and leave to cool and infuse for about an hour.

Squeeze the muslin bag back into the pan to extract as much flavour as possible, then discard it. Reheat the infused milk gently, then add the grated chocolate and stir until it has melted.

In a separate bowl, whisk the egg yolks with the sugar. Pour on the hot cream mixture and whisk gently to combine. Pour the mixture back into the rinsed-out pan and cook gently until it thickens to a custard consistency. You should be able to draw a distinct line through the custard on the back of a spoon. Remove from the heat immediately and cool in a sink of iced water. Stir from time to time as the mixture cools down.

Spoon the coffee cream into petit pots or little glasses and chill before serving.

MAKES 8

Dried fruit compote

Grapes, apricots and figs are all grown in abundance in Turkey, and after the harvest a good supply is dried in the late-summer sun before being set aside for the winter. Dried fruit compotes, known as ho af, are very popular throughout Turkey, where they are sometimes served after the main part of the meal spooned over plain pilav. Ho

af, are very popular throughout Turkey, where they are sometimes served after the main part of the meal spooned over plain pilav. Ho af range from simple raisin compotes to brightly coloured combinations of apricots, figs, prunes and currants, sometimes with the addition of nuts.

af range from simple raisin compotes to brightly coloured combinations of apricots, figs, prunes and currants, sometimes with the addition of nuts.

You’ll find the barberries and tiny wild Turkish dried figs in Middle Eastern food stores, and some gourmet shops too.

250 g caster sugar

250 ml water

½ stick cinnamon

2 cloves

4 cardamom pods

long piece of peel from 1 orange

long piece of peel from ½ lemon

75 g dried wild figs

100 g dried apricots

cup currants

cup currants

¼ cup barberries

Combine the sugar and water in a heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring occasionally until the sugar dissolves. When the syrup is clear, add the spices and citrus peels, then increase the heat and bring to the boil. Add the dried fruit and simmer for 5 minutes. Remove from the heat and leave the fruit to cool in the syrup.

Transfer to an airtight container and refrigerate until ready to use. The compote will keep for up to a week.

SERVES 4–6

Sticky dried fig puddings

A variation on the universally popular sticky date pudding, this is a perfect winter warmer. The figs are less sweet and toffee-like than dates, and this particular recipe makes a surprisingly light sponge pudding.

As well as with the butterscotch sauce, you could also serve it with custard or lightly whipped cream.

225 g dried figs, finely chopped

450 ml boiling water

1½ teaspoons bicarbonate of soda

90 g unsalted butter (at room temperature)

250 g caster sugar

3 free-range eggs

1 teaspoon ground ginger

250 g self-raising flour

BUTTERSCOTCH SAUCE

225 g unsalted butter

200 ml thickened cream

330 g soft brown sugar

Preheat the oven to 170ºC and butter 12 x 150–200 ml small metal moulds, a 25 cm square cake tin or a 25 x 20 cm baking tray.

Put the figs, boiling water and bicarbonate of soda into a bowl, then stir well and leave to stand for 20 minutes.

Cream the butter and sugar in an electric mixer until light and fluffy. Add the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Mix the ginger into the flour, then sift onto the pudding mixture and fold in gently. Stir in the fig mixture and pour into the prepared moulds, then bake for 15 minutes.

While the puddings are baking, make the butterscotch sauce. Combine all the ingredients in a heavy-based saucepan and bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 5 minutes. Stir occasionally, but don’t overwhisk or the sauce will crystallise.

After 15 minutes baking, spoon a little sauce on top of each pudding, then return to the oven for a further 5 minutes, or until cooked when tested with a skewer.

To serve, unmould the puddings onto dessert plates, then invert them so the sticky surface is uppermost. Serve with extra sauce.

MAKES 12