Slightly perplexed to learn that we’d have to get up at 5 am to enjoy this breakfast, we were even more alarmed to discover that it was going to be grilled liver kebabs - a challenge for anyone at that early hour, we felt.

The next morning saw us rising before the pigeons and the sunrise. We had arranged to meet a new friend, Filiz Hösuko lu, for what we expected would be a rather challenging breakfast.

lu, for what we expected would be a rather challenging breakfast.

We’d met Filiz, a Gaziantep local, the previous day. She proved to be a font of knowledge about the city’s culinary ‘must dos’, turning up to lunch armed with a list of places to visit and people to meet. Her enthusiasm was infectious. ‘Tomorrow morning we will visit my friend Ali Bey and we will have ci er kebab, a traditional Antep breakfast,’ she’d chirped. Slightly perplexed to learn that we’d have to get up at 5 am to enjoy this breakfast, we were even more alarmed to discover that it was going to be grilled liver kebabs - a challenge for anyone at that early hour, we felt.

er kebab, a traditional Antep breakfast,’ she’d chirped. Slightly perplexed to learn that we’d have to get up at 5 am to enjoy this breakfast, we were even more alarmed to discover that it was going to be grilled liver kebabs - a challenge for anyone at that early hour, we felt.

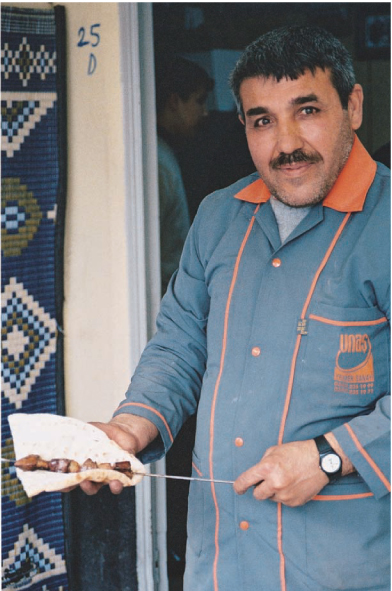

Our taxi edged its way down a narrow alleyway near the town market towards a crowd of men gathered outside a tiny hole-in-the-wall diner. We stumbled, bleary-eyed, over to Filiz, who was chatting cheerfully to Ali Bey, the liver chef. The air was blue with smoke rising from the grill and the place was bristling with purpose. Little clusters of tough-looking men crouched against the wall, or squatted on stools around low tables eating. Others were milling around in front of the grill, leaning in every now and then to help Ali Bey turn the skewers or to offer suggestions.

We stood around stomping our feet in the chilly morning air, admitting to Filiz, somewhat cautiously, that yes, it did indeed smell quite delicious. We sat down, squeezing in next to a balding man in an open-necked shirt and leather jacket, who glanced at us bemusedly. A few moments later Ali Bey came over to show what was on offer for breakfast. He proudly thrust a large tray of neatly arranged kebabs under our noses for us to choose. As well as calf’s liver there were also kebabs of diced heart or kidney. In each case, the chunks of offal were alternated with lumps of lamb’s tail fat to keep them moist over the fierce heat of the grill.

Greg’s eyes lit up and he chose one of each; the rest of us were more restrained. Ali Bey whisked our selections off to the grill while his teenage son brought over the traditional kebab accompaniments. Onto the table went a battered tin plate of fresh parsley, mint and spring onions; next came four little bowls of ground cumin, sumac, salt and chilli flakes; and finally, bottles of cold ayran, the traditional yoghurt-drink accompaniment for liver kebabs.

A little while later Ali Bey returned to our table brandishing our cooked kebabs. He deftly off-loaded them into soft floppy circles of flat bread and we sprinkled on our preferred garnishes. By now it was nearing 7 am and most of his customers had taken themselves off to work. He sat down next to us, smiling; pleased to see how much we were enjoying breakfast. With Filiz translating, Ali Bey told us that he’d been working the liver grill for nearly forty years, having taken over the business from his father, Haydar. Every morning he got out of bed at 3 am in order to select and prepare the best-quality offal for his customers. His ci erci was open at 5 am sharp and the last customers were served at 7 am.

erci was open at 5 am sharp and the last customers were served at 7 am.

He laughed when we asked him about this seemingly bizarre custom of eating kebabs for breakfast. ‘You know, Turks in this part of the country really love offal, but the liver kebab, it’s a real Gaziantep thing,’ he explained. ‘In the winter it’s cold and snowy here and liver kebabs make a good hot start to the day before you head off to work. And anyway, everyone knows liver is good for you; it builds up your strength and your blood.’

Little clusters of tough-looking men crouched against the wall, or squatted on stools around low tables eating. Others were milling around in front of the grill, leaning in every now and then to help Ali Bey turn the skewers.

We were ready for some exercise, so we said our goodbyes and set off back to our hotel. The streets were coming to life. Bakeries and pastry shops were doing a brisk trade and, as we approached the covered markets, stall-holders were setting up their stands for the day. We wandered up and down the spice section, fascinated by the gleaming jars of pickles and the wide range of dried herbs and spices on offer. There were countless varieties of red pepper flakes to choose from as well as massive barrels of red pepper paste, each with a slightly different flavour.

Stalls were festooned with garlands of dried eggplant, okra or chillies, others were piled high with hunks of gently oozing honeycomb or marbled blocks of halva.

Stalls were festooned with garlands of dried eggplant, okra or chillies, others were piled high with hunks of gently oozing honeycomb or marbled blocks of halva. We drooled over the range of dried apricots and pestil - dried fruit leathers - and inspected bottles of myriad types of molasses from grape and carob, to mulberry and sumac. Metal buckets of all shapes and sizes contained yoghurt and different kinds of brined cheese; tulum, a crumbly white goat’s cheese, was especially fascinating as it is drained and matured in the goat’s hairy hide. We were also curious to see displays of tarhana wafers. Tarhana is similar to Lebanese kishk, it’s made from a fermented mixture of wheat and yoghurt that is dried in the sun. In Turkey it’s more commonly sold in powdered form, which is used to make a sort of instant soup.

On the outskirts of the noisy copper bazaar we passed a row of forlorn-looking Kurds, squatting on the pavement with their wares spread out on thin blankets in front of them. Among the thin nylon tracksuit pants and day-glo orange socks there were little mounds of vine leaves and plastic tubs of fresh green almonds. A trio of hollow-cheeked men in baggy suits tended a large samovar of bubbling tea and, all of a sudden, breakfast seemed a long time ago. It was time to head back to our hotel for a spot of refreshment and a bit of a sit down.

Orange preserve

We enjoyed a version of this delectable preserve at many a Turkish breakfast. Much runnier than traditional jam, it is equally delicious with soft white cheese, creamy yoghurt or bread and butter. I also use a spoonful to garnish sweet citrus tarts, to fold through ice-creams or to drizzle over milk puddings. Adding a spoonful to cake or brioche batter adds a wonderful citrus tang too.

Don’t feel limited to using oranges – you can use any citrus peel or combination of citrus peels you like.

1 kg oranges

500 ml water

650 g sugar

Peel the oranges, removing as much pith as you can from the peelings. Slice the peel into thin strips. Bring a small saucepan of water to the boil, then add the peel and return to the boil. Leave for 10 seconds then drain. Repeat this process twice more, changing the water each time, to remove any bitterness.

Combine the 500 ml water and sugar in a large, heavy-based saucepan over a gentle heat, stirring occasionally, until the sugar has dissolved. Add the orange peel and cook at a bare simmer (65ºC on a sugar thermometer) for 30 minutes or until the peel is soft.

Remove the pan from the heat and ladle the orange preserve into sterilised jars. Pour on enough syrup to cover completely and seal while still hot. The orange preserve will keep up to 12 months in a cool place.

MAKES 750 ml

Quince preserve

Large, floral-scented quinces grow in abundance around Turkey. They’re used in the late autumn to make compotes, jams and jellies, preserves and candies, and are also added to savoury casseroles.

2 kg quinces

1 stick cinnamon

sugar

1 tablespoon orange-blossom water

Peel and core the quinces, reserving everything. Put the peelings and cores into a large, heavy-based saucepan. Slice the fruit thickly and arrange it on top of the peelings with the cinnamon stick. Pour on enough cold water to just cover the sliced quince, then press a piece of greaseproof paper cut to size down over them. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer until the sliced quinces are very tender, around 30 minutes.

Use a slotted spoon to transfer the sliced quinces to a bowl. Raise the heat under the saucepan and boil vigorously. Every now and then crush the peelings and cores with a potato masher to extract as much pectin as you can. When they have reduced to a mushy pulp, about 10–15 minutes, tip the contents of the pan into a jelly bag or muslin square suspended over a very large bowl. Leave to drain overnight.

Measure the collected juice and add 500 g sugar to each 600 ml juice. Put the juice and sugar into a large, heavy-based saucepan and stir well over a low heat until the sugar has dissolved, then bring to the boil.

Add the reserved sliced quinces to the saucepan and boil over a high heat for 20 minutes, or until the preserve reaches the setting point. To test, spoon a small amount onto a cold plate and place in the refrigerator to cool. The preserve is at setting point if it forms a skin that wrinkles when you push your finger through it. When the preserve is ready, remove the pan from the heat and skim any froth from the surface. Stir in the orange-blossom water.

Divide the preserve between sterilised jars, making sure the quinces and jelly are evenly distributed. Seal and store.

MAKES 1 kg

Pickles and preserves

While in Istanbul we found ourselves staying in the same neighbourhood as Asri Tur ucu, one of the city’s oldest and best-known pickle shops. Most days, as we set out on our daily adventures around the city, we would somehow find ourselves in front of this small corner shop, drawn by the stunning window display of pickles, gleaming like jewels in the morning sunlight. Inside, too, the shelves were stacked high with jars of all shapes and sizes.

ucu, one of the city’s oldest and best-known pickle shops. Most days, as we set out on our daily adventures around the city, we would somehow find ourselves in front of this small corner shop, drawn by the stunning window display of pickles, gleaming like jewels in the morning sunlight. Inside, too, the shelves were stacked high with jars of all shapes and sizes.

One morning we did a quick tally of the produce on offer, identifying jars of cucumbers, red and green peppers, chillies, cabbage, beetroot, string beans, onions, okra, tomatoes, garlic and stuffed eggplant. And then there were more unusual items, such as medlars, pine cones and whole ears of corn, as well as a variety of pickle juices for drinking. Eventually we stopped counting, realising that in Turkey just about every vegetable or fruit can and will be pickled!

The tradition of preserving summer’s bounty is certainly alive and well in Turkey, and there are pickle shops in almost every town and village. In the cities, naturally enough, fewer people have the opportunity or time to indulge in home pickling, but in rural areas, come harvest time, it’s still an annual tradition to lay down the season’s surplus produce to brighten up mealtimes through the long cold winters.

All manner of vegetables are pickled in a simple vinegar-brine solution and fruits are preserved whole in sugar syrup or made into jams and jellies. The hot summer sunshine also makes it easy to dry fruit and vegetables. Tomatoes, peppers, apricots, figs and grapes are dried whole, or fruits are pounded into pastes and dried to form chewy fruit leathers known as pestil. Turkish markets stock an extraordinary range of pestil, sometimes jazzed up with nuts or coconut and rolled up to make a sweetmeat called kume.

One of the most widely used Turkish preserves is pekmez, a sort of molasses made from boiled fruit pulp. Pekmez is traditionally used as an all-purpose sweetener, and in many rural areas villagers still prefer it to sugar. It’s generally made from grapes, but we also found versions made from pomegranates and mulberries, quince, apple and date. Pekmez is poured over desserts and ice-creams, or eaten as a sort of dip with bread. I use it with abandon, sloshing it into soups, stews and sauces, and even salad dressings, where it adds an indefinable sour-sweetness that I adore.

Spicy eggplant relish

If there is one ingredient that best sums up Turkey, it must undoubtedly be the humble eggplant. In the summer, the markets are overflowing with mounds of eggplants in myriad shapes and sizes; in the winter, strings of dried eggplants hang like exotic necklaces in the bazaars, waiting to be reconstituted in water, stuffed and braised in oil. In Turkey the eggplant is the king of the vegetables and lends itself to endless cooking styles, from grilling to baking, stuffing, puréeing, marinating, pickling and even being candied or turned into jam. It would be fair to say that I love eggplant as much as the Turks do!

2 large eggplants, peeled and cut into 2 cm cubes

sea salt

100 ml olive oil

2 large onions, grated

8 cloves garlic, roughly crushed

1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons sweet paprika

2 tablespoons ground cumin

2 large vine-ripened tomatoes, skinned, seeded and diced

6 long red chillies, thickly sliced

2 tablespoons caster sugar

juice of 2 lemons

Put the cubed eggplant into a colander and sprinkle liberally with salt, then leave for 30 minutes or so to drain. Briefly rinse, then pat dry and set aside.

Heat the oil in a large, heavy-based frying pan. Squeeze the grated onion well to extract as much juice as you can, then add to the pan with the garlic and spices and sauté over a high heat for 5 minutes. Add the tomatoes and chillies and cook for 2 minutes, then add the sugar and the eggplant cubes and season with salt.

Cook over a low-medium heat for about 30 minutes, stirring frequently to make sure nothing catches and burns. Towards the end of the cooking time add the lemon juice. Remove from the heat and allow to cool. The relish will keep in the refrigerator for up to a week.

MAKES 1 kg

Sweet pickled garlic

This recipe was inspired by an eighteenth-century Ottoman recipe. The strength of the garlic softens in the pickling liquor, and the cloves make a wonderful accompaniment to cold meats or salads.

1 kg garlic

2 tablespoons coriander seeds

1 tablespoon white peppercorns

500 ml white-wine vinegar or apple vinegar

1 litre water

2 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons currants

Separate the garlic cloves and remove any excess papery skin. Place in a large, non-reactive saucepan with the remaining ingredients except for the currants and bring to the boil. Lower the heat slightly and simmer for 10–15 minutes, until the garlic is tender. Remove from the heat and stir in the currants.

Divide the ingredients between the two sterilised 500 ml jars, then seal and turn them upside-down a few times to distribute the ingredients evenly. Leave in a cool, dry place for a month before using. The garlic will keep in the refrigerator for up to a month after opening.

MAKES 1 kg

Pickled onion rings in rose vinegar

These lightly pickled onion rings are delicious with cold and smoked meats and make a great addition to any salad – especially tomato salads. This is not a pickle to set aside and store – it needs to be eaten soon after it’s made. My greengrocer calls the long purple onions I use here ‘Tuscan onions’. The main benefit of using them for this pickle is that when cut the rings are fairly even in size, and not too large.

100 ml red-wine vinegar

V teaspoon sea salt

1 teaspoon mild honey

2 long purple onions, cut into thickish rings

splash of rosewater

slivered pistachios to serve (optional)

In a bowl, stir the vinegar, salt and honey until the salt and honey have dissolved. Add the onion rings and toss thoroughly, then leave to macerate for an hour. Just before serving, add a splash of rosewater and, if you like, a scattering of slivered pistachios.

SERVES 4

Pickled Onion Rings in Rose Vinegar)

Partly dried tomatoes with pomegranate

Partly drying really ripe tomatoes in a very slow oven – or in the full sun of summer – concentrates the sugars. Sweet–sour pomegranate molasses complements the flavours beautifully. Use them as part of a mezze selection – as you would sun-dried tomatoes – in salads, pilafs or sauces, or as an accompaniment to cold meat or charcuterie.

2 kg small vine-ripened

roma tomatoes, cut in half

lengthwise

100 ml extra-virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons pomegranate molasses

sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 50ºC. Place the tomatoes, cut-side up, on metal racks fitted into baking trays (you’ll probably need two). Whisk together the oil and pomegranate molasses and lightly brush each tomato with this. Sprinkle with salt and pepper and bake for 5 hours until the tomatoes have shrunk and shrivelled. Remove from the oven and leave to cool on the rack.

Arrange the cooled partly dried tomatoes in layers in a shallow container, separating each layer with greaseproof paper. They will keep in the refrigerator for up to 10 days.

MAKES 1 kg

Pickled cucumbers with fennel

In her wonderful book 500 Years of Ottoman Cuisine, Marianna Yerasimos writes that eighteenth-century Ottoman recipes combined fennel with cucumbers and garlic to make a wonderful crunchy appetiser. I love the mild aniseed flavour of young fennel and was inspired to create this pickle. It makes a wonderful addition to any mezze table.

700 pickling cucumbers

6 baby fennel bulbs

4 small bullet chillies,

pricked with the point

of a small knife

8 cloves garlic

1 tablespoon fennel seeds

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

1 stick cinnamon, broken in half

1 litre water

150 ml white-wine vinegar

60 g sea salt

2 tablespoons sugar

Wash the cucumbers, then prick them all over with a thin skewer or toothpick. Trim the stalks of the fennel bulbs evenly and cut the bulbs into quarters lengthwise.

Divide the cucumbers, fennel, chillies and garlic between two sterilised 500 ml jars, layering them with the spices as you go and making sure that a piece of cinnamon stick goes into each jar.

Bring the water, vinegar, salt and sugar to the boil in a large, non-reactive saucepan. Pour the boiling liquid into the jars, ensuring there are no air pockets and that the vegetables are submerged. Seal the jars and turn them upside-down a few times to distribute the ingredients evenly. Leave in a cool, dry place for a week before using. The pickles will keep in the refrigerator for up to a month after opening.

MAKES 1 kg

[Clockwise from left] Pickled Cucumbers with Fennel, Partly Dried Tomatoes with Pomegranate, Spicy Eggplant Relish

Long green pepper pickle

This pickle is made from long, mild green peppers – although it works equally well with hot peppers. Pickled peppers and chillies are often served at the start of a Turkish meal to stimulate the appetite.

1 kg long green peppers

2 red bullet chillies

4 cloves garlic

1 tablespoon coriander seeds

1 litre water

400 ml white-wine vinegar

60 g sea salt

1 cup mint leaves, washed and dried

Wash the peppers and chillies, then prick them all over with a thin skewer or toothpick and set aside in a large ceramic bowl or dish.

In a large, heavy-based, non-reactive saucepan, combine the garlic, coriander seeds, water, vinegar and salt. Bring to the boil and pour over the peppers and chillies. Leave to macerate until cold.

Return everything to the saucepan and return to the boil. Divide the mint between two sterilised 500 ml jars, then divide the pepper mixture as well and pour in the liquid. Seal the jars and turn them upside-down a few times to distribute the ingredients evenly. Leave in a cool, dry place for a week before using. The pickles will keep in the refrigerator for up to a month after opening.

MAKES 1 kg

Snow almonds or walnuts

Soaking nuts in chilled water over several days causes them to swell up and become wonderfully crunchy. In Turkey these nuts are often served on a bed of ice, which keeps them moist and cold. Serve them with pre-dinner drinks as a refreshing nibble – they seem to go especially well with raki.

200 g raw almonds or walnuts

Put the nuts into a container and cover with cold water, then seal and refrigerate for 3–4 days.

Drain the nuts and rub away the skins. Rinse well, then return to the container and cover with fresh cold water. Leave until ready to serve – up to a week.

MAKES 250 g

Candied walnuts

This walnut praline makes a great garnish for all sorts of desserts, especially creamy mousses or ice-creams, where they add a lovely sweet crunch. I also use them in the apricot ice-cream for the Flower of Malatya.

150 g caster sugar

2 tablespoons water

200 g walnuts

Combine the sugar and water in a heavy-based saucepan over a gentle heat, stirring occasionally to dissolve the sugar. When the syrup is clear, increase the heat and bring to a rolling boil. Cook for about 5 minutes until the syrup reaches the thread stage at around 110°C (a drop of the syrup will fall from a wooden spoon in a long thread).

Add the walnuts to the pan – the sugar mixture will crystallise as the oils come out of the nuts. Lower the heat and stir gently until the crystallised sugar dissolves back to a caramel. This will take around 10–15 minutes. Carefully pour the hot caramel onto a baking sheet lined with baking paper or greased aluminium foil. Smooth with the back of a fork and allow to cool and harden. When cold, break into chunks with a rolling pin, then pound to crumbs in a mortar and pestle.

MAKES 250 g

Baharat

Baharat is a sort of all-purpose spice mix used widely around the Middle East and Turkey. The Arabic word literally means ‘spices’ – and the spice recipe varies from region to region and family to family. Many spice shops will sell their own house-blend. This is a fairly typical Turkish-style blend with just a touch of heat. It’s infinitely versatile and I like to use it in braises and slow-cooked stews. Mixed with oil and crushed garlic it makes a terrific marinade for lamb chops and roasts and for barbecued game or poultry.

5 tablespoons sweet paprika

5 tablespoons freshly ground black pepper

¼ cup ground cumin

2 tablespoons ground coriander

2 tablespoons ground cinnamon

1 teaspoon hot paprika

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

Mix the spices thoroughly and store in a jar for up to 3 months.

MAKES 200 g

Flavourings

Turkish cooking makes excellent use of a wide range of herbs, spices and other aromatics – although never allowing them to dominate the flavour of the core ingredient of a dish.

Herbs are used in large quantities, with mint, dill and parsley being the most popular. Herbs are generally used fresh – and they are certainly available in abundance – although occasionally dried herbs are preferred for specific dishes. For instance, some soups and dips, such as cacik, call on dried mint, often in addition to the fresh herb – the dried herb provides a mellow, subtle background flavour, while the fresh provides a top note that lifts the palate. There are also clear regional preferences, of course, with basil, oregano and thyme featuring especially prominently along the Mediterranean and Aegean coastline. Interestingly, unlike Arab cooking, where the fresh herb dominates, coriander is rarely used in Turkish cooking.

In the ancient world, the very earliest spice routes from the Orient passed through Anatolia on their way west, so it’s not surprising that allspice, cinnamon and cumin are popular in the rural Turkish kitchen, while Istanbul cooks have always had a rather lighter hand. With the discovery of the New World in the fifteenth century new ingredients such as tomatoes, peppers and chillies flooded into Anatolia and were taken up with alacrity.

It is perhaps the capsicum family that is now the most important ingredient in Turkish cooking as it is responsible not only for the fresh peppers and chillies enjoyed with nearly every course of every meal, but also for the dried, ground and flaked preparations used in myriad ways every day.

The best red peppers are said to grow in southeastern Turkey near Kahramanmara , Gaziantep and Şanliurfa, with each variety having its own distinctive flavour. Urfa peppers are dark red or purple-black and lend a wonderful smoky depth to dishes. The dark-red peppers from Mara

, Gaziantep and Şanliurfa, with each variety having its own distinctive flavour. Urfa peppers are dark red or purple-black and lend a wonderful smoky depth to dishes. The dark-red peppers from Mara are full-bodied and aromatic, while Antep’s peppers are lighter red and a little milder. All these red peppers have a high oil content, and look moist and a little shiny, rather than dull and dry. Sometimes they will be roasted before use, which turns them a blackish colour and makes them more potent.

are full-bodied and aromatic, while Antep’s peppers are lighter red and a little milder. All these red peppers have a high oil content, and look moist and a little shiny, rather than dull and dry. Sometimes they will be roasted before use, which turns them a blackish colour and makes them more potent.

Of the dried peppers, red pepper flakes – kirmizi biber – have a particularly special place in Turkish cuisine, and range from sweet and mild to fiercely hot depending on the region. As well as being used in all sorts of savoury dishes, they are often stirred into sizzling butter (sometimes with dried mint) to make a wonderful final touch to soups.

Hot or mild Turkish red pepper flakes are available from specialist or Turkish food stores and are well worth hunting out for their distinctive flavour, which is more warm and spicy than really hot. Once you’ve enjoyed their smoky aroma and rich, earthy flavour you’ll be hooked.

Paprika is another pepper preparation that’s used with abandon in the Turkish kitchen. Its flavour is sweeter and milder than that of the red pepper flakes, but this too varies in strength and style depending on the region. Turks tend to use sweet paprika and hot paprika; smoked paprika, often sold as Hungarian paprika, is used to a lesser degree.

As well as being used on their own, spices and dried herbs are often combined in Turkish cooking to make spice mixes. These differ depending on their use – some will be sweeter, some spicier, some more pungent. The following are some of my favourite combinations.

Poultry spice mix

This spice mix is a lovely balance of sweet, salty, sour and hot. I use it with all sorts of poultry dishes, as well as with other white meats such as rabbit, veal and pork. It also works very well with vegetable dishes – especially those featuring eggplant, zucchini or fennel.

cup ground allspice

cup ground allspice

2 tablespoons ground cinnamon

2 teaspoons hot paprika

2 teaspoons ground sumac

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Mix the spices thoroughly and store in a jar for up to 3 months.

MAKES 70 g

Seafood spice mix

The addition of fennel seeds and lemony coriander makes this blend particularly well suited to fish dishes, especially those using crustaceans. Mix it with flour and use it to dust pieces of fish for pan-frying or grilling. Its slight curry flavour also lends itself to egg dishes, pulses and vegetables, even pilavs.

cup sweet paprika

cup sweet paprika

2 tablespoons ground cumin

2 tablespoons ground coriander

1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

1 tablespoon ground fennel

Mix the spices thoroughly and store in a jar for up to 3 months.

MAKES 100 g

Köfte spice mix

A universally popular spice mix that works with all sorts of köfte and  i

i kebabs. You can also use it in a marinade for grilled beef or lamb dishes. The dried mint makes it taste particularly Turkish.

kebabs. You can also use it in a marinade for grilled beef or lamb dishes. The dried mint makes it taste particularly Turkish.

cup ground cumin

cup ground cumin

cup dried mint

cup dried mint

cup dried oregano

cup dried oregano

2 tablespoons sweet paprika

2 tablespoons freshly ground black pepper

2 teaspoons hot paprika

Mix the spices thoroughly and store in a jar for up to 3 months.

MAKES 160 g

Lamb spice mix

The warmth of cumin combined with sweet and hot paprika bring out lamb’s natural sweetness beautifully. Try mixing this with a little oil and rubbing it onto a leg of lamb before roasting, or sprinkle it onto tiny chops or lamb straps before grilling or frying.

2 tablespoons ground cumin

2 tablespoons sweet paprika

1 tablespoon hot paprika

1 tablespoon ground nutmeg

1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

Mix the spices thoroughly and store in a jar for up to 3 months.

MAKES 70 g