The beauty and scale of Topkapi unfolds in a series of linked courtyards, and we passed through a succession of lush gardens, ornately vaulted stone chambers and exquisitely tiled pavilions …

On our last day in Istanbul, we walked across the Galata Bridge from Beyo lu to Sultanahmet. Things were exactly the same as they’d been a few weeks before, except then there had been a chill wind blowing off the Bosphorus and the March drizzle had smudged the spires and domes of the Old City skyline into a soft grey monochrome. Now the weather was warmer, tulips were blooming and the scent of spring was in the air.

lu to Sultanahmet. Things were exactly the same as they’d been a few weeks before, except then there had been a chill wind blowing off the Bosphorus and the March drizzle had smudged the spires and domes of the Old City skyline into a soft grey monochrome. Now the weather was warmer, tulips were blooming and the scent of spring was in the air.

Pushing our way through the jostling crowds around the Eminönü ferry terminal, we headed west to trudge up the hill towards the Topkapi Palace. We wandered along a street named So ukçe

ukçe me Sokak, with its quaint old wooden houses built right up against the palace walls, until we found ourselves outside the Imperial Gate.

me Sokak, with its quaint old wooden houses built right up against the palace walls, until we found ourselves outside the Imperial Gate.

The residence of the Ottoman sultans for four centuries, the Topkapi Palace is perfectly situated on the top of a hilly wooded promontory at Seraglio Point. There were monasteries and public buildings on this site in Byzantium times, but the massive complex of pavilions and gardens that occupy the site today was built by Sultan Mehmet II after his dramatic conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

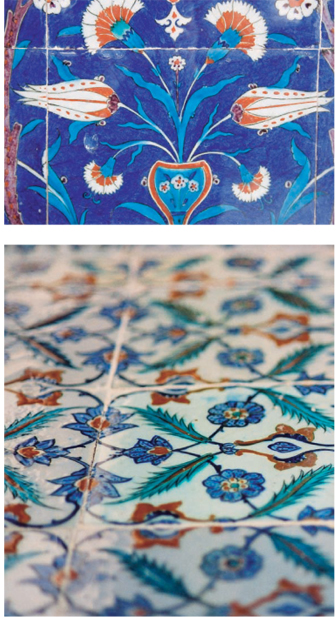

The beauty and scale of Topkapi unfolds in a series of linked courtyards, and as we passed through a succession of lush gardens, ornately vaulted stone chambers and exquisitely tiled pavilions it was easy to believe that at its peak this place was more a miniature city than a royal residence.

The administrative heart of the entire Ottoman Empire was gathered here at the palace; government and cabinet ministers, foreign ambassadors and the elite military corps known as the Janissaries all lived here, side by side with the sultan and his harem. When the Ottoman Empire was at the height of its power, the kitchens fed an average of 5000 people every day. On feast days and other special occasions this number could easily double – you can only wonder what the food bills would have been like.

It was a lot of mouths to feed and, from the very beginning, food was of prime importance to palace life. When he built the Topkapi, Mehmet II included a huge four-domed kitchen, and over successive centuries this was gradually extended to form the complex that remains today. As we discovered, beneath the distinctive twin rows of domes and chimneys was a whole little world in its own right: the kitchen complex was not just where cooking was done, but it also housed pantries and storerooms, administrative offices, sleeping quarters for kitchen staff, a mosque and a bathhouse.

The palace kitchens were manned by a brigade of highly specialised staff. At its largest, there was a team of almost 1400 cooks and assistants, including pilav chefs, baklava chefs, köfte makers and kebab chefs, bakers, confectioners and pickle makers, to name but a few. And in the way that chefs in today’s finest restaurants devote a lot of their time to reading magazines and cookbooks from countries all around the world, the chefs of Topkapi Palace did the same in their day, borrowing ideas from far-flung lands and adapting and reinventing them for the sultan’s pleasure.

Of course, the palace cooks were lucky. As the Ottoman Empire expanded, so did their repertoire. Not only was Constantinople itself a vast food market, with new and exotic foodstuffs coming in every day from all corners of the empire and beyond, but the growth of the empire led to a continuous exchange and cross-fertilisation of culinary ideas and recipes across its lands and peoples, providing plenty of inspiration for the chefs.

By the time of Suleiman the Magnificent – the Empire’s golden age – cooking had been elevated to an art, and food was celebrated in song, poetry and exquisitely painted miniatures. Chefs competed to create ever-greater culinary masterpieces and foreign visitors to the court returned home to tell tales of lavish banquets, where 300 or more dishes were eaten on floors spread with richly embroidered cloths against a backdrop of tinkling fountains and music in the air.

Relics of this devotion to the pleasures of the table are still on display. In the kitchens we inspected pots and pans, kettles and cauldrons and all sorts of other cooking paraphernalia, as well as a vast collection of Chinese porcelain. Other rooms housed displays of the more delicate trappings of this elite lifestyle; we gazed, awestruck, at dishes from  znik painted with tulips, carnations and pomegranates; delicately engraved pudding spoons and jewelled carafes.

znik painted with tulips, carnations and pomegranates; delicately engraved pudding spoons and jewelled carafes.

We wandered happily around the buildings and gardens, making our way towards the far end of the palace grounds to a broad terrace overlooking the water. We stood for a while in the warm sunshine gazing out to where the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara meet, and then over to the Asian shore in the distance.

We had one more mission before our Turkish journey came to an end. Clambering off a busy tram back at the Eminönü waterfront, we headed for the Spice Bazaar. We cut through the imposing Yeni Mosque, emerging on the other side to the ablution fountain where we looked across to the rooftops of the Spice Bazaar, domed like some strange metal egg-carton. In the chambers above the imposing gatehouse entry were the windows of the famous Pandeli restaurant, one of the oldest and most prestigious in the city. But, for now, we walked inside the bazaar to see where the palace cooks did their shopping.

Little has changed in Misir Çar isi – the ‘Egyptian’ Spice Bazaar – since it was built in the early seventeenth century. Now, as then, along its cavernous, dimly lit walkways you could find spices from the Orient, caviar and tea from the Black Sea, olives from Greece and exotic fragrant oils from Arabia. We squeezed our way up and down the crowded walkways and it was as if we were reliving our entire Turkish journey of the last five weeks. At one stall we found olive oil from Ayvalik, at another there was tulum cheese in a traditional goatskin sack and bright-red smelly pastirma from Kayseri, while around the corner, we spotted Aleppo pepper flakes, pistachio coffee and tarhana from Gaziantep.

isi – the ‘Egyptian’ Spice Bazaar – since it was built in the early seventeenth century. Now, as then, along its cavernous, dimly lit walkways you could find spices from the Orient, caviar and tea from the Black Sea, olives from Greece and exotic fragrant oils from Arabia. We squeezed our way up and down the crowded walkways and it was as if we were reliving our entire Turkish journey of the last five weeks. At one stall we found olive oil from Ayvalik, at another there was tulum cheese in a traditional goatskin sack and bright-red smelly pastirma from Kayseri, while around the corner, we spotted Aleppo pepper flakes, pistachio coffee and tarhana from Gaziantep.

Produce from all around the country was available – dried apricots from Malatya, golden raisins from Izmir, wild greens from the Aegean coast, fish from the Bosphorus and the Mediterranean. There were great dark oozing blocks of honeycomb, buckets of creamy yoghurt, sackfuls of bulgur wheat, necklaces of tiny dried okra, and mounded displays of nuts, fruits and sweetmeats as far as the eye could see. All this great Anatolian abundance was on display right here in the heart of Istanbul.

Emerging into the sunshine, we found that the narrow streets outside the Spice Bazaar were chaotic. It was just an ordinary weekday, but it seemed as if the entire population of the city was here doing business or its daily shopping. We pushed our way through the heaving crowds of shoppers – past the simit sellers with their trolleys of bread, past stalls offering pomegranate juice or a glass of hot sahlep, past eager young Turks keen to sell us plastic dolma-rollers and gypsy women offering bunches of luridly tinted carnations – and ducked into a small tea house to catch our breath.

The noise of the crowd faded away and we sat for a moment in silence, our conversation stilled by a sudden sense of melancholy. Although unvoiced, I was sure that we shared the same thought: ‘It’s too soon to leave this place.’ I pulled out my notebook and flicked back through the pages; five weeks’ worth of scribblings rose up from the pages in a tangle of disjointed words, phrases and expressions. Every meal we’d eaten had its own story – in the names of the new friends we’d made, the restaurants visited, the ingredients discovered, the dishes tasted. It is true that the purpose of our journey had been about the small, simple things of daily life … about food and eating and cooking. But the real joy had been in the way these small things revealed this country’s history and the lives of its people.

Every meal we’d eaten had its own story – in the names of the new friends we’d made, the restaurants visited, the ingredients discovered, the dishes tasted.

I glanced down at my notebook again, at the jottings of quotes and notes of conversations we’d had, and memories and faces came flooding back. In my mind’s eye I could see Talat Ça da

da ladling hot sugar syrup over a tray of golden baklava; Musa Da

ladling hot sugar syrup over a tray of golden baklava; Musa Da deviren talking animatedly of his passion for Anatolian peasant food; Filiz and The Fish Doctor, and Hüsna Baba with his sea urchins; Emine with her enchanting smile and Sedat pouring us yet another glass of raki. All these people, and many more, had shared their passions, had helped and taught us, had fed and hugged us and had shown us their Turkey. Our journey had certainly been a celebration of food, but what would the food be without the people?

deviren talking animatedly of his passion for Anatolian peasant food; Filiz and The Fish Doctor, and Hüsna Baba with his sea urchins; Emine with her enchanting smile and Sedat pouring us yet another glass of raki. All these people, and many more, had shared their passions, had helped and taught us, had fed and hugged us and had shown us their Turkey. Our journey had certainly been a celebration of food, but what would the food be without the people?

A moment later, a waiter appeared, setting down on the table in front of us pretty little tulip-shaped glasses of strong, sweet tea. As we thanked him, he smiled and asked the same question that we’d been asked so many times over the last few weeks: ‘Where you from? You spik Ingleez? You like Turkey?’ We smiled back and assured him that, yes, we did like Turkey very much indeed.

Sticky apricots stuffed with clotted cream

Deep-amber and ivory in tone, these popular Turkish sweet treats are exquisitely pretty – and they taste sensational. Make sure you use good-quality, large dried apricots; in Turkey the best apricots come from Malatya and these are exported all around the world. It can be difficult sometimes to find whole dried apricots, in which case you’ll have to use apricot halves and sandwich them together. The cream used in Turkey is kaymak, a thick clotted cream made from buffalo milk. Lightly sweetened mascarpone, créme fraîche and strained yoghurt are the best alternatives if you can’t find kaymak.

Pekmez, or grape molasses, is available from Turkish food stores.

350 ml water

2 tablespoons caster sugar

½ stick cinnamon

6 cardamom pods, lightly crushed

2 tablespoons pekmez

1 tablespoon lemon juice

250 g dried apricots (preferably whole)

250 g clotted cream, mascarpone or Strained

Yoghurt

additional caster sugar

2 tablespoons finely ground or slivered unsalted shelled pistachios

Combine the water and sugar in a heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring occasionally, until the sugar dissolves. When the syrup is clear, add the cinnamon, cardamom, pekmez and lemon juice, then increase the heat and bring to the boil. Add the apricots, then lower the heat a little and simmer for 20 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and leave the apricots to cool in the syrup.

Remove the apricots from the syrup and let them drain for a moment in a sieve. Reserve the syrup. Sweeten the cream with a little sugar to taste. If you are using whole apricots, slit them carefully along one side and fill them generously with cream. If using apricot halves, sandwich them together with a spoonful of cream. Arrange the stuffed apricots on a serving plate and chill. When ready to serve, sprinkle each apricot with pistachios and drizzle with a little syrup.

SERVES 4–6

Harem navels

Many Turkish pastries and desserts have names as sensual as the treat itself. Should the urge take you, you can nibble on ‘ladies’ thighs’, ‘beauty’s lips’, ‘vizier’s fingers’ or ‘harem navels’. The latter are small, syrup-drenched doughnuts, also known as lokma, and I like to stud them with a hazelnut, just to reinforce the belly-button idea.

These are delicious served warm with ice-cream.

3 teaspoons dried yeast

600 g plain flour

pinch of sea salt

70 g unsalted butter (at room temperature)

cup caster sugar

cup caster sugar

440 ml milk

3 free-range eggs

1 free-range egg yolk

vegetable oil for deep-frying

peeled roasted hazelnuts to garnish

candied orange peel to garnish (optional)

ORANGE SYRUP

300 ml caster sugar

100 ml water

2 tablespoons orange juice

finely grated zest of 1 orange

1 tablespoon corn syrup

To make the syrup, combine all the ingredients in a large, heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Bring to the boil, then remove from the heat and leave to cool.

Mix the yeast, flour and salt in a large bowl. Put the butter into another large bowl. Gently heat the sugar and milk in a saucepan, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Do not boil. Pour the milk mixture onto the butter and stir to melt, then leave to cool to lukewarm. Whisk the eggs and egg yolk into the milk mixture, then stir this into the flour by hand until the batter is smooth. Cover the bowl and leave in a warm, draught-free spot for 1 hour, by which time the dough should have doubled in size. (The batter can be made to this stage up to a few hours ahead of time. Keep in the refrigerator to slow the yeast activity, but allow 2–3 hours at room temperature before recommencing.)

When ready to cook, heat the oil in a large saucepan or deep-fryer to 180ºC. Spoon the batter into a piping bag fitted with a wide, plain nozzle and hold it above the hot oil. Squeeze gently, snipping the batter into small, even round blobs as it falls. The doughnuts should be about the size of a small walnut. Fry 8–10 doughnuts at a time for 1½–2 minutes until a deep golden brown. Move them around in the oil with a large slotted spoon, so they colour evenly. Scoop the doughnuts out of the oil straight into the pan of syrup and leave for a few minutes to soak.

When cool enough to handle, stud each doughnut with a hazelnut and garnish with candied peel, if using.

MAKES 30–40

Yoghurt biscuits with sesame and pistachios

Versions of these nutty biscuits can be found in bakeries all over Turkey. I particularly like this recipe as the biscuits have a soft, almost cake-like texture and are not too sweet.

heaped  cup sesame seeds

cup sesame seeds

¼ cup unsalted shelled pistachios

150 g unsalted butter, softened

¼ cup soft brown sugar

¼ cup icing sugar

1 vanilla pod, split

2 free-range eggs 180 g thick natural yoghurt

350 g self-raising flour, sifted

1 free-range egg yolk

2 tablespoons milk

Pulse the sesame seeds and pistachios in a food processor to coarse crumbs.

Cream the butter and sugars in an electric mixer until light and fluffy. Scrape in the vanilla seeds, then add the eggs and beat until incorporated. With the motor on low, add the yoghurt and mix gently to combine. Tip in the sifted flour in one go and mix briefly until just combined. Add a quarter of the pistachio mixture to the bowl and mix through briefly. Refrigerate the dough for 30 minutes before baking to firm up.

Preheat the oven to 170ºC. Grease and line two baking sheets. Lightly beat the egg yolk with the milk to make an egg wash.

Take little pieces of the dough and roll them into balls about the diameter of a 10 cent piece, then flatten them slightly to form discs around 1 cm thick. Bake for 10 minutes, then remove from the oven. Working quickly, brush the surface of each biscuit with a little egg wash and scatter with the remaining pistachio mixture, pressing it on gently. Return to the oven for another 2 minutes, then transfer the biscuits to a wire rack to cool.

MAKES 30

Fairy chimneys

I created these crazy-shaped meringues as a reminder of the rocky, wild Cappadocian landscape, with its twisted ‘pillars’, cones and knobbed ‘turrets’, euphemistically known as fairy chimneys. You’ll need a piping bag to make these meringues, but only basic piping skills. You’re not aiming for perfection here; in a way, the wilder they look, the better!

The addition of cornflour makes the meringues slightly soft and marshmallowy inside. The idea is to make a tall base ‘pillar’ and to top it with a broader, domed meringue. If you make it large enough, the base pillar can be filled with cream. Otherwise, serve a big bowl of cream on the side so that everyone can help themselves, along with fresh fruit such as figs and mandarins.

5 free-range egg whites

200 g caster sugar

200 g icing sugar

1 tablespoon cornflour

400 ml whipping cream

additional caster sugar (optional)

vanilla extract (optional)

Preheat the oven to 120ºC. Line two baking sheets with baking paper.

Put the egg whites and a few tablespoons of the caster sugar into a scrupulously clean electric mixer. Whisk on a low speed until the mixture begins to foam, then increase the speed to high and whisk until the foam thickens to form smooth, soft glossy peaks. Sift on the remaining caster sugar a little at a time, whisking to firm peaks as you go. Finally, sift on the icing sugar and cornflour and whisk in briefly until incorporated.

Spoon the meringue into a piping bag fitted with a smallish nozzle and pipe 10 pillars, about 4 cm in diameter and 5 cm high. Refill the bag and pipe the 10 tops: make them the same height, but slightly broader in diameter than the bases and coming to a peak at the top.

Bake for 1½ hours until the meringues are ivory-coloured and crisp. Leave to cool on the baking sheets for 10 minutes before carefully lifting them onto a wire rack to cool completely.

When ready to serve, whip the cream, sweetening it with a little sugar and flavouring it with a drop or two of vanilla extract – or add your own flavourings. Fill the pillars with the cream and sit the peaked domes on top, using a little of the cream to secure them, if necessary. Otherwise, serve the cream alongside. Either way, serve straight away.

MAKES 10

Walnut and semolina cake with honey and cinnamon

This moist, syrup-soaked cake is surprisingly light and springy. The Frangelico adds a lovely depth to the syrup, and the lemon juice cuts the sweetness. Serve with afternoon tea or coffee, or as a dessert with whipped cream.

150 g walnuts

225 g unsalted butter

200 g thick natural yoghurt

100 g caster sugar

100 g mild honey

270 g fine semolina

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1½ teaspoons baking powder

FRANGELICO SYRUP

50 ml mild honey

150 g caster sugar

160 ml water

juice of 1 lemon

3 cardamom pods, lightly pounded

1 stick cinnamon

50 ml Frangelico

Preheat the oven to 170ºC. Grease and line a 22 cm springform cake tin.

Chop the walnuts roughly by hand. Melt the butter in a heavy-based frying pan, then add the walnuts and fry for a few minutes to allow some of their oil to flavour the butter. Remove the pan from the heat.

In a large bowl, whisk the yoghurt, sugar and honey. Add the walnut mixture and whisk to combine, then whisk in the semolina, cinnamon and baking powder. Pour the mixture into the prepared tin and bake for 20 minutes.

While the cake is baking, make the syrup. Combine all the ingredients except the Frangelico in a heavy-based saucepan and bring to the boil. Lower the heat and simmer for 5 minutes, then remove the pan from the heat and strain.

When the 20 minutes’ baking time is up, remove the cake from the oven. Add the Frangelico to the syrup and ladle it over the cake. It seems like a lot of syrup, but the semolina cake will drink it up! Return the cake to the oven and bake for a further 8 minutes. Remove from the oven and leave to cool in the tin. When cold, cut the cake into squares and serve.

SERVES 12

Sultana yoghurt cake

This cake is light and airy, a sort of Turkish cheesecake. It gets its tang from thick creamy yoghurt, and has none of the palate-sticking graininess of many cheesecakes.

Serve this cake warm or cold with pouring cream.

¼ cup sultanas, roughly chopped

muscat or sherry

5 free-range eggs, separated

80 g caster sugar

2 tablespoons honey

80 g plain flour, sifted

500 g thick natural yoghurt

finely grated zest and juice of 1 lemon

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

Preheat the oven to 180ºC and grease and line a 20 cm springform cake tin.

Put the sultanas into a small bowl with just enough muscat to cover them and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Drain and set aside.

In an electric mixer, beat the egg yolks, sugar and honey until thick and creamy. Gently mix in the flour, followed by the sultanas, yoghurt, zest, juice and oil. Mix on a low speed until well combined.

Whisk the egg whites until stiff and stir a spoonful into the yoghurt mixture to slacken it, then gently fold in the remaining whites, taking care to keep the mixture light and airy. Pour into the prepared tin and bake for 50–60 minutes, until the cake has puffed up like a soufflé and the top is browned.

Remove from the oven and leave in the tin for a few minutes to cool and subside. When the cake begins to shrink away from the sides of the tin, use a knife or spatula to loosen it, then unclip the springform tin and leave the cake to cool.

SERVES 6–8

Nightingale nests

⅔ cup walnuts

½ cup unsalted shelled pistachios

2 heaped tablespoons caster sugar

½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

6 sheets filo pastry

melted unsalted butter

SUGAR SYRUP

200 g caster sugar

200 ml water

1 stick cinnamon

long piece of peel and juice from ½ lemon

Preheat the oven to 180ºC. Grease a baking tray.

To make the syrup, combine the sugar, water, cinnamon stick and lemon peel in a heavy-based saucepan and heat gently, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer gently for 5 minutes. Remove from the heat, then add the lemon juice and set aside to cool.

Pulse the nuts, sugar and cinnamon to fine crumbs in a food processor.

To make the nightingale nests, work with one sheet of filo at a time and keep the rest covered with a damp tea towel. Place a sheet of pastry on your work surface and brush with a little melted butter. Fold the filo sheet in half, bringing the short sides together. Swivel the pastry rectangle so a short side is facing you. Brush with a little more butter and scatter on a generous amount of the nut mixture.

Lie a long metal skewer or a chopstick across the end of the filo rectangle facing you and roll the pastry around it and away from you to create a tight log. Brush the pastry log with melted butter. With the skewer still in place, gently push both ends of the pastry log inwards, wrinkling up the pastry, until the log is around 12 cm long. Gently pull out the skewer and coil the wrinkled log into a ‘nest’ shape. Use a spatula to lift it onto the prepared baking sheet. Continue working with the remaining filo sheets and nut mixture until you have six neat bird’s nests – you should still have some nut mixture left.

Brush the nests with butter and bake for 20 minutes, or until golden brown.

Shortly before the end of the cooking time, bring the syrup to a boil. Remove the pastry nests from the oven and stand the baking tray on a high heat on your stove top. Cook for a minute, turning continuously (this helps make the bottoms of the pastry good and crisp). After a minute pour on the boiling syrup, then immediately remove the tray from the heat. Leave the pastries in the tray to soak up the syrup as they cool.

When ready to eat, fill the middle of the nests with more of the nut mixture and serve.

MAKES 6

Turkish coffee

Making coffee is something of an art form in Turkey. It is prepared and served as a way of signalling respect and affection for one’s guests. You will usually be asked to specify whether you wish to drink it ‘az  ekerli’ (with a little sugar), orta

ekerli’ (with a little sugar), orta  ekerli (with a moderate amount), ‘çok

ekerli (with a moderate amount), ‘çok  ekerli’ (with a lot of sugar) or

ekerli’ (with a lot of sugar) or  ekersiz (without sugar). To enjoy Turkish coffee, you need to get your head around the fact that the coffee is not strained before serving, and that the sugar is added to the coffee as it brews, not afterwards. The grounds that remain at the bottom of the cup are used for fortune-telling.

ekersiz (without sugar). To enjoy Turkish coffee, you need to get your head around the fact that the coffee is not strained before serving, and that the sugar is added to the coffee as it brews, not afterwards. The grounds that remain at the bottom of the cup are used for fortune-telling.

It’s best to make Turkish coffee in a cevze, a small, long-handled pot, but a small saucepan will suffice.

2 tablespoons finely ground, medium-roast Turkish coffee

180 ml water

sugar to taste

Combine all the ingredients in a cevze and stir well. Bring to the boil slowly over a low heat. Watch the pot carefully: remove the cevze from the heat immediately a thick foam forms on the surface and begins to rise. Carefully divide the foam (not the liquid) between two small coffee cups, being careful not to disturb or disperse it.

Return the cevze to the heat and boil briefly. Pour the coffee into the cups carefully and slowly, again being careful not to disperse the foam. Serve straight away.

SERVES 2

Coffee and coffee houses

Europeans have the Ottomans to thank for introducing them to coffee. Originating in Ethiopia, the wild coffee arabica bush is believed to have been cultivated by African tribesmen from the sixth century AD, who enjoyed it for its stimulating properties, rather in the same way that we enjoy it today. From Ethiopia, the use of coffee spread over the Red Sea to Yemen, and then its popularity swept rapidly through Arabia.

By the sixteenth century, the consumption of coffee had become fashionable in Mecca, Damascus and Constantinople, where the first true coffee house was established in 1554. Despite efforts by the pious to ban it because of concerns about its mind-altering properties, coffee drinking spread like wildfire. Within a few decades Constantinople was full of coffee houses and by the end of the sixteenth century there were reputedly more than 600 coffee houses in the city alone.

The pleasure of coffee was embraced by the Ottoman Empire. By 1700 there were coffee houses as far afield as Venice and Marseilles. In 1669, Sultan Mehmet IV sent an emissary to the courts of Louis XIV to woo the palace with various Ottoman delights: coffee was served from delicate long-spouted ewers, ladies’ hands were sprinkled with rosewater and all manner of sweetmeats were served. Subsequently, coffee was spruiked around the country by wandering coffee vendors sporting traditional Turkish costume as a mark of their trade.

Vienna’s love affair with coffee dates from the Ottoman siege of the city in 1683, when retreating Turkish armies reputedly left behind sacks of coffee beans that they’d brought with them. An enterprising Pole, Franz Kolschitsky, who was familiar with coffee having once served as an interpreter in the Ottoman army, prepared the beans in the traditional manner and thus introduced the Viennese to the delights of drinking coffee.

It’s not hard to see why coffee was such an instant hit, especially in Muslim countries where alcohol was prohibited. In fact, the English word coffee comes from the Turkish kahveh, which comes from the old Arabic word for wine – kawhah.

Coffee houses have largely always been men’s domain. The earliest coffee houses were often constructed as pavilions, and, as is the case with fancy restaurants today, the most favoured were the ones with a good view of the city, the Golden Horn or the Bosphorus. Customers reclined upon low benches and smoked fragrant tobacco – sometimes opium – through slender water pipes. Entertainment was provided and they generally operated as a kind of gentleman’s club, where men would while away the hours chatting or reading the daily newspapers. Over time, coffee houses became inextricably linked with prayer. Often sited next to mosques, these two institutions were generally the main places for social gathering in a village or town.

Today coffee houses – kahve – tend to be rather down-at-heel, dingy places, and they continue to be more often frequented by men than by women or family groups. Inside you’ll find little groups of men playing cards or backgammon and smoking endlessly. And despite the name and the long history, the drink of choice in coffee houses these days tends to be tea!

Ayran

This chilled yoghurt drink is a popular all over Turkey, especially in the summer months. It’s sold in bottles and little cartons, and in some villages it’s sold churned from large wooden barrels to make it light and fluffy. Ayran is the drink to serve with kebabs and köfte. When we ate our liver kebab breakfast in Gaziantep, chef Ali told us that he couldn’t conceive of eating any meal without ayran and that, when he was growing up, if there was no ayran on the table his grandmother would refuse to eat the meal.

500 ml chilled thick natural yoghurt

250 ml chilled water

½ cup crushed ice

sea salt

dried mint to serve (optional)

Blend all the ingredients, except the dried mint, in a vitamiser until light and frothy. Serve immediately in tall chilled glasses, sprinkled with a little dried mint, if you like.

SERVES 4

Tamarind sherbet

Tamarind – or ‘Indian date’ as it translates from the Turkish – has a wonderfully tart flavour and is used to make this lovely thirst-quencher. Restaurants and wandering drink vendors often sell this chilled drink in the summer months.

250 g tamarind

1 litre water

250 g caster sugar

Soak the tamarind in the water overnight.

The next day, bring the soaking tamarind to the boil slowly, then remove the pan from the heat and leave to cool. Strain through muslin into a clean jug, then stir in the sugar until dissolved. Decant into a sterilised bottles and refrigerate.

This sherbet will keep in the refrigerator for up to five days. After opening, drink within two days. Serve chilled, with extra sugar if you like.

MAKES 1 litre

Morello cherry and rose sherbet

450 g morello cherries

500 g caster sugar

500 ml water

1 teaspoon rosewater

crushed ice to serve

Put the cherries into a large, heavy-based saucepan and cover with the sugar. Leave for several hours, or overnight.

Add the water to the pan and heat gently, stirring until the sugar dissolves. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 15 minutes. Strain the juice into another saucepan. Press the cherries with a potato masher over the pan to extract as much juice as you can, then discard the fruit. Simmer the juice gently until reduced to a thick syrup. Leave to cool in the pan, then stir in the rosewater and decant into sterilised bottles.

Store in a cool place for up to 12 months. After opening, use within two months. To serve, dilute the sherbet with still or sparkling water and serve with crushed ice.

MAKES 1 litre

Citrus sherbet

This refreshing summer drink can be made from just about any combination of citrus fruits, or any on its own.

500 ml water

200 g caster sugar

200 ml orange juice

100 ml lemon juice

finely grated zest of 1 orange

finely grated zest of 1 lemon

crushed ice to serve

mint leaves to garnish

Put all the ingredients into a large heavy-based saucepan and heat slowly until the sugar has dissolved, stirring, then bring to a boil. Lower the heat and simmer, uncovered, for 20 minutes. Leave to cool, then strain into sterilised bottles.

Store in a cool place for up to 12 months. After opening, use within two months. To serve, dilute the sherbet with still or sparkling water and serve with crushed ice and garnished with mint leaves.

MAKES 1 litre

Pomegranate caprioska

Tom Lovelock, a friend and MoMo barman, dreamt up the following Turkish-inspired cocktails for us.

V lime, cut into 4 wedges

50 ml vodka

30 ml pomegranate juice

1 teaspoon caster sugar or sugar syrup

crushed ice to serve

Place two wedges of lime in a cocktail shaker with the vodka, pomegranate juice and sugar or syrup. Muddle the ingredients together, then add plenty of ice and shake well.

Strain into a lowball glass filled with crushed ice. Garnish with the remaining 2 lime wedges.

SERVES 1

Tangerine dream

For this summery cocktail try to use a gin with crisp citrus undertones, such as Tanqueray No. Ten.

45–60 ml Tanqueray No. Ten

5–8 mint leaves

2–3 drops orange-blossom water

ice cubes to serve

tangerine juice to taste

1 sprig mint

Put the gin, mint leaves and orange-blossom water into a highball glass filled with ice cubes and stir well. Pour on tangerine juice to taste and garnish with a sprig of mint.

SERVES 1

Turkish delight martini

This exquisitely pretty martini combines the classic Turkish delight flavours of chocolate and rosewater. You can buy rose-flavoured syrup, which tints this cocktail the palest of pink hues.

½ lemon or lime

drinking chocolate

45 ml vodka

3 teaspoons white créme de cacao

3 teaspoons good-quality rose syrup

2–3 drops rosewater

rose petals to garnish (optional)

Rub the rim of an elegant chilled martini glass with the lemon or lime, then dip into a saucer of drinking chocolate.

Combine the vodka, créme de cacao and rose syrup in a cocktail shaker with a handful of ice. Stir well, then strain into the martini glass. Add a few drops of rosewater and garnish with rose petals, if you like.

SERVES 1

Hazelnut martini

The spiciness of chillies and vodka and the tang of lime combine beautifully with warm, sweet cinnamon and Frangelico to make a wonderful cocktail for winter evenings.

Adding a stick of cinnamon to one part sugar and two parts water makes for a heady sugar syrup to use here. Reserve a few tablespoons of the cinnamon syrup and candy a few chillies to use as a garnish – it’ll take this martini to another height altogether!

30 ml pepper vodka or chilli-infused vodka

30 ml Frangelico

3 teaspoons lime juice

1 teaspoon cinnamon sugar syrup

candied chillies or chilli flakes to garnish

Combine the vodka, Frangelico, lime juice and sugar syrup in a cocktail shaker with a handful of ice.

Stir and strain into a chilled martini glass. Garnish with candied chillies or sprinkle with chilli flakes.

SERVES 1

[From left] Turkish Delight Martini, Pomegranate Caprioska