/ CHAPTER 1

The Trouble of Intimacy

Rinaldo Walcott

Kinship is a wonderfully strange relation. Austin Clarke and I came to be kin. And, in the manner of most kinships, we shared an intimacy that I still struggle to make sense of. These works collected in ’Membering Austin Clarke are striking for the intimacy the contributors share in their engagement with Clarke’s writing and his life. Leslie Sanders’s epistolary reflection on women in Clarke’s work; Dennis Lee on their shared youth and editing Clarke; Sonnet L’Abbé on meeting him and his influence on and support of her; Katherine McKittrick on his library; John Harewood’s exchange of personal letters with Clarke; Patrick Crean’s experience as his long-time editor (The Prime Minister and The Polished Hoe) and close friend; and George Elliott Clarke on visiting Clarke’s childhood neighbourhood in poetic form—all these evoke a certain kind of intimacy with Austin Clarke. And where the contributions verge on a more immediate intimacy, the readings and analyses of Clarke’s novels, short fiction, and poetry all work at another level of intimacy within the fiction to reveal in detail the significance of Clarke’s contributions, even when the representation he leaves us as readers troubles us. The mark of intimacy in this collection is, I think, very much conditioned by the fact that Clarke’s own point of view as a writer was one of a carefully crafted and minutely documented observation of his surroundings. Clarke’s fiction therefore always brings his readers into the intimate lives of his characters—from Dots to Bernice to Boysie to Mary-Matilda to Idora, as any reading of his work makes immediately evident.

Intimacy is double-edged, though. I do not remember when I first met Austin Clarke. I do know that Dionne Brand introduced me to him sometime in the early 1990s and that we became fast friends. One of the sore points of our friendship was my significant lack in documenting my encounters and therefore my life. I do know that I had my first martini with Clarke (gin, the only way he felt a martini should be made) and I know that once becoming friends, we spent countless hours together in his home, in mine, and at bars and restaurants around Toronto. He loved sushi (California rolls in particular) and I was the one who introduced him to this cuisine. I still recall him exclaiming that his mother would be outraged he was eating raw fish. He grew dreadlocks when I challenged him to do so after seeing his uncombed hair (I, too, wore dreadlocks). For a period of about four to five years I rented and lived in the first-floor apartment of Clarke’s house at 150 Shuter Street; prior to that he lived on St. Nicholas Street and I lived on St. Joseph Street. We grew to know each other well. He introduced me to his friends, his lovers, his acquaintances (of which there were many), and even to a distant relative of mine. (I would later find out that Clarke briefly lived with this relative and his family in Barbados. He was in his teens. I now take this story as somehow connected to the cosmic reason we became such good friends.) We were fully conscious of our friendship and often spoke about how a then-younger Black gay man (myself) and a mature, well-respected writer and public figure had forged such a friendship, even if our politics did not always align. We were often mistaken for father and son (he always insisted this was impossible because he was more handsome than me). Our kinship was a strangely pleasurable one. One thing was certain, though: we were both Fanonians and loved Black people.

The desire to vindicate a friend, a mentor, a father figure who has passed on is a strong one. I will continue to resist the impulse to do so with Clarke’s work and his interlocutors. But let me pursue for a brief moment Clarke’s relationship to women, both in his work and in his life, which was a deeply complicated one. Clarke, like most men, was a patriarch. It is not damning to make such a claim. His patriarchy was, if we could qualify the claim, of the soft kind. He loved women, he was afraid of women, especially his mother, and he was obviously conflicted by women in his writing and in his personal life.

If my argument about the intimacy of Clarke’s writing holds, then, it is also a key to reading his female characters. Clarke’s depiction of women was often an extension of women he knew in his own life. The fictional was never far from the real and I have met women who have successfully read themselves in his novels. Clarke did not dispute their readings and or the details of a particular scene and those women’s memory of it as it actually occurred. Clarke’s women characters are sometimes difficult to read because he attempts to offer us the details of lives that he observed, might have participated in, and as a way to come to terms with (his) masculinity. His work records how women are victimized and exalted and also demonstrates how he experienced women as both full of resourceful strength and as a force to reckon with. In many ways Clarke’s fictional women are a composite of his mother and other women from his intimate life. I think we will have to seriously grapple with why women play such central and powerful roles in his fiction beyond their sometimes faulty representation. Thus, for me, it is not so much that Clarke is a misogynist as much as his writing spectacularizes misogyny in our culture. I do not offer this distinction as an apologia, but rather in an attempt to make some space for further insight into the man I came to intimately know.

If we read Clarke’s writing of the city alongside his writing of women, the same mode or logic is at work. You can map Clarke’s beloved Toronto through his writing. In Clarke’s work Toronto is simultaneously intimate partner and vicious lover. From jazz clubs to street names to bars, Clarke’s Toronto is one that invites and repels simultaneously. The short story “Canadian Experience” is at one end of Toronto, the end that repels, and in More Idora’s Kensington Market is at another end of Toronto, the inviting end. In the former the experience is driven toward suicide and in the latter Idora is lusciously enveloped in food, people, scents, and sounds. In both, the intimacy of life that I think underpins Clarke’s writing is made evident. In Clarke’s literary geography of Toronto, we are taken up in the intimacy of the city as a character fraught with all the problems, troubles, and double-edged affect that intimacy involves.

The archive of Clarke’s life will never convey the intimacy that undergirded his passions. This anthology maps intimacy too through photography and Clarke’s literary notes, his handwriting and photos of his edits. The photographs offer some sense of what Clarke’s life might have been like. Clarke curated those photographs much in the manner of his crafting of a work of fiction. Food, music, and good company were central to the environment that Clarke worked to create and those environments also became the source for his writing. For example, when we hung out at the Sutton Place Hotel at Wellesley and Bay in the late 1990s, often for lunch, and found Coltrane playing, Clarke often claimed it was playing because they knew he was coming. Curation was central to his life—from cooking to dressing up or down to music to the carefully orchestrated invitation of guests to a meal or the selections of martini and wine for a party. And with Clarke, like any good artist, curation was also a kind of intimacy that could not be fully trusted either.

Since Austin Clarke joined the ancestors I have grappled with the double-edged nature of our intimate friendship and resisted the impulse to position myself as an arbiter of his legacy. Clarke is one of Canada’s most important post–World War II writers and the first significant Black one. His contributions anticipated the multicultural present we now live in, and the detailed documentary process of his writing also leaves us documents of how we arrived where we are at in Canada today. In Canada, Black people and Blackness remains firmly adjacent to the national narrative that continues to imagine itself as white, a whiteness that Clarke’s work spectacularizes for the violence it does to Black life. Clarke’s writing career was touched by and informed by the brutality of Canada’s white violence too. Given his contributions, one would think that he and his work would be a staple of what we now call CanLit in all of its manifestations and permutations. The story is otherwise. Indeed, some will seek to produce him as the grandfatherly incitement for their own institutional reach and as either a minor figure or a strawman that they must displace. Those attempts at minimization and displacement should be roundly refused. As Black studies becomes more institutionalized in Canadian universities, Clarke’s contributions will be significant for understanding post–World War II Black life and white confrontations with Black emergence in that period. Clarke’s life and work, therefore, demonstrates how in Canada Blackness and Black people are called on, discarded, and disremembered at will. This anthology, however, stands as a refutation of that ongoing problem for Black life in Canada.

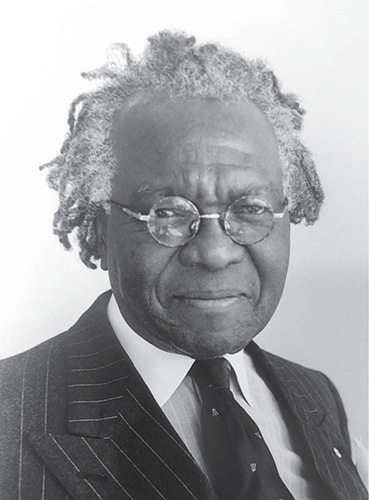

Austin Clarke.

Permissions: William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library