/ CHAPTER 11

Austin A.C. Clarke Is the Most

Kate Siklosi

While poring over some of Clarke’s early poetic manuscripts—which are heavily revised, and bear the night scars of slashes, rhetorical questions, and remedied inaccuracies—I came across something seemingly rare in Clarke’s literary and personal oeuvre: an inward, romantic communing with nature at his casement’s ledge. While most of the more current writing and scholarship on Clarke’s work focuses, rightly so, on the exterior worlds he imagined, lamented, and celebrated within the city of Toronto, his early poetry betrays a sense of interiority and a yearning identification with the natural world. A lot of Clarke’s political writing throughout his career lingers on the boundary between the exterior world, the interior spaces of his characters’ minds, and the domestic spaces they inhabit; in these early poems, we see him experimenting with the thresholds of these borders. In his meditations on the natural world outside his window, he is writing through the co-production of identity between inside/outside, and undoing such binaries—as the city moves, breathes, and seethes, so the mind of the poet acts in response.

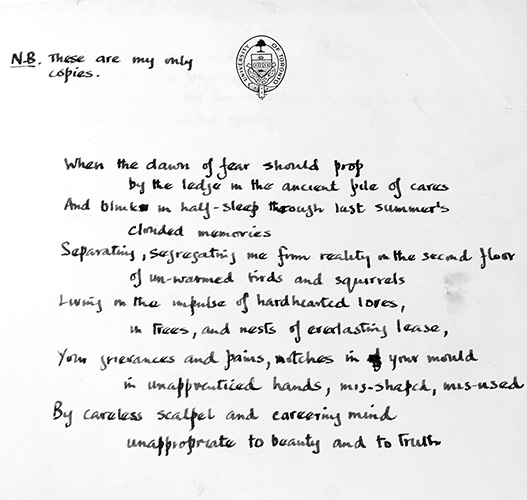

I came across two undated, handwritten poems—an “original,” and then the revised and rewritten version, both written in Clarke’s characteristic sprawling calligraphy—reminiscent of the dance of an ink-dipped spider drunk with elegant intent. The first poem I assume to be the first draft, since its form is much more tentative upon the page: it lacks the formal tightness and structure of the second, and the second has airs of Clarke painstakingly ruminating over the “right” descriptors, searching for the “proper” perspective to cloak the poem’s intent. The poems are left undated, but based on their placing in Clarke’s archives (and the fact that the second poem is written on University of Toronto letterhead), these poems were likely written in 1958 and 1959, while Clarke was a student at Trinity College.

As a young writer cutting his teeth as a poet, this mode also could be a means for Clarke to learn the craft he would, unfortunately, abandon for most of his career. Although his revisions are mostly to alter the meaning of the words themselves—“uncurtained birds and squirrels” in the first version becomes “unwarmed birds and squirrels” in the second—Clarke is also ever so slightly experimenting with form in these early poems.

The first draft is ten lines long, with lines one to four, seven, and ten written in a form roughly resembling iambic decapentasyllable, a Byzantine metre also known as “political verse.” Political verse is known for the rhythmic movement created by its metre. When Clarke rewrote the poem, he split up some of the lines so that the “new” poem is twelve lines of varying lengths (roughly, longer lines followed by shorter ones) arranged in non-rhyming couplets with the second lines dropped or indented from the left margin. But the movement inherent in the political verse form is retained in this updated draft; the imagery and rhythm of the pastoral scene of “birds and squirrels / Living on the impulse of hardhearted loves, / in trees, and nests of everlasting lease,” carries a musicality that suggests human connection and communion with nature. Early in his career, Clarke was introduced to the Romantic poets and the modernist T.S. Eliot. One of his earliest pieces of juvenile poetry, “We Are the Half-Born Men,” is an obvious play on Eliot’s infamous “The Hollow Men,” a poem about hopeless immobility. Judging by Clarke’s struggle to articulate natural worlds, both interior and exterior, across an axis of influence, it is plausible that he is experimenting with form using these writers as guides, their work serving as Baedekers with which he can imprint his own understanding of selfhood and interiority onto the world.

Political verse, or politikos stichos—“the verse of the polis and its citizens”—was also used as a poetic “form of the people” in the Byzantine Empire during the thirteenth century. I’m not suggesting here that Clarke was aware that he was writing in political verse form, or was even aware of it, but I found the resemblance, coupled with Clarke’s literary polemic of engagement with the city and with citizenship, to be striking. Moreover, given Clarke’s classical education and his literary apprenticeship with poet and editor Frank Collymore, founder of the Bajan literary magazine Bim, it seems plausible that Clarke could be adapting this classical form in his work, or at least might have been aware of it.

In its traditional use, political verse is not meant to imply a political tone or polemic, per se, but it was used as a secular form in medieval and modern Greek poetry. In Clarke’s poems, we do not see a transcendental attribution of feeling to faith, but rather an exposition on the writing process itself as a secular practice. Although “the city” is mediated in these early Clarke poems through a landscape that does not signify as overly urban—he describes the view as more pastoral, with birds, squirrels, trees, and nests—the concerns of the outside world are latent, and they foreshadow the urban themes that would preoccupy most of his writing. In the first version of the poem, the opening line reads, “When the dawn of day props by the ledge,” and this line is revised in the second version as “When the dawn of fear should prop / by the ledge.” This revision of “day” to “fear” signals a foreboding sense of anticipated threat that emanates from the outside world, infiltrating the window of Clarke’s house and soul.

Moreover, it is this inciting moment wherein the exterior world enters the poet’s mind that initiates a process of metapoetic discovery in the remainder of the poems. The day’s summoning, punctuated by the careless and carefree existence of the flora and fauna, leads him to reflect upon his own “grievances and pains,” articulated through his “unapprenticed hand.” The poems thus unfold a complex psychic landscape through the writing process, one that is mottled with self-discovery and self-doubt. As he meditates on the world outside his window and writes, the perfect and “everlasting lease” of the natural world’s “beauty” and “truth” remind him of the perceived “unappropriateness” of his “mould.” This perceived inadequacy could signify the poetic apprentice’s self-doubt, or it could be Clarke ruminating on the inability of language to accurately describe beauty or truth—that it is an inherently flawed medium that can only gesture toward eternality and truth, hopelessly.

The ledge, however, becomes a psychic barrier; the dawn of day/fear “props by the ledge,” meaning it does not necessarily cross the threshold of the window but tickles its boundary. In this way, Clarke signals an interiority that resists the imposing structures and ideas of the outside world; the window, then, becomes a significant site of potential resistance and psychic/physical protection from outside forces. Speaking of the window as a threshold, Clarke writes in the third line of the first version, “Separating and segregating me from a lower order.” He then alters the line to “Separating, segregating me from reality on the second floor.” This is an interesting revision, for in both he is playing on “separation” and “segregation” as racially loaded terms, and in the first he aligns his inability to articulate the essence of beauty and truth in nature as indicative of his “lower order.” However, in the second version, the lower order becomes the safe haven of the second floor of his house—the site, presumably, from which he sits at his window ledge. Moving from an exterior, social reality—his racialized body as “lower order”—to a protective, domestic space signals the house as a threshold to the outside, but also as a haven that protects him, and allows him to trespass (if only in and through the moment of writing) the boundaries and structures of the outside world.

Thus, although these poems are not directly concerned with physical movement, in their rhythmic structure, and in their play with the window or “doorway,” to borrow Dionne Brand’s term, between inside and outside, they perform an incredible thought movement. It is significant that movement was a central concern of Clarke’s throughout his writing career. Movement toward, movement from, movement between—these are means by which language can mobilize our particular imaginaries. Bodily movement, but also thought movement, becomes both an aesthetic and political act, especially in the context of the city, wherein the social structures are deeply racialized. In writing about the dreams of colonial subjects as narratives of possibility, Frantz Fanon, in Black Skin, White Masks, argues that these “are muscular dreams, dreams of action, dreams of aggressive vitality. I dream I am jumping, swimming, running, and climbing” (15). Movement, for Fanon, becomes a means by which the racialized body—whose movement is striated by exterior structures of control and containment—can imagine agency and possibility beyond the constraints of colonial order and its material structures. In Clarke’s early poems, the city represents a space of unattainable and inimitable “beauty” and “truth,” a space that he cannot attempt to recreate with his “unapprenticed hands, mis-shaped, mis-used / By careless scalpel and careering mind.” He doesn’t so much describe physical movement, but the psychic movement that takes place at the ledge of the window, the threshold between public and private.

At the window, Clarke articulates the Fanonian paradox of hope through the lens of the metapoetic process: he admires the animals outside the window for their natural freedom of movement, and yet his perceived inability to write accurately about his connection and communion with this outside world is conveyed with uncertainty and doubt, as if he is contained or restrained by his lack of ability to “make it cohere,” as Pound says (Canto 116, 816). Again, this constraint could signify Clarke’s revelling in the very inability of language, flowing through the vehicle of his hand, to accurately portray such truths he sees reflected in the outside world. Constraint, then, could be construed as a refusal to impose closure on meaning through writing, instead opting for an “everlasting lease” on that which we cannot know and can only imagine.

His hesitancy is perfectly marked by the line “Austin A C Clarke is the most,” written below the first draft of the poem. I linger on this fragment. Is it an interrupted attempt to describe himself? A halted moment of confession, diary, self-questioning from an otherwise publicly proud man? Such questions make me uncomfortable, for working with the archives of a writer—especially when that writer has manuscripts written feverishly on napkins or coffee-stained foolscap with late-night meanderings noted in the marginalia—always seems like an act of trespassing. But the incompleteness of this sentence struck me, and I could not resist.

We see here a poet who is unconfident at least, and yet striving, poignantly, toward precision—a man experimenting with form and process, conveying his view of the transcendent connections between public and private worlds. It is the discordances and correspondences that surface in the metapoetic process—the struggles to define the world and the poet in it accurately on the page—that make the writing process part and parcel of a lived, practised reality integrated with dreams of moving potential, thresholds of desire as yet undone by exterior forces of containment and governance. Although he cannot replicate the truth and beauty of the outside world on the page, the very act of writing allows him to meet the city on the level of co-production and exchange. For Clarke, the natural world abides by a natural order that conveys its “truth”—as such, the poem becomes a space wherein the poet may gesture toward truth and knowledge, but the grand mystery of the world is forever left elusive. It is a poetics ruled not by the singular exactness of the facts, but the productive interchange between actors in an environment.

Clarke’s window provides a view of the poet entering into a relationship of exchange and encounter with the outside world, but it’s useful to think of the other window through which we encounter our world: language. In these early poems, we see Clarke experimenting with language, acutely aware of how slight turns in meaning can alter the axis and rotation of the poem as a whole. Language is a mediator between what is fixed and rigid and what is fluid and ungraspable. It is the window between structure and immensity, the pane against which we place our soul when we write. And whether or not we have the right words at the right time, the accurate thought and movement, is irrelevant. As Dionne Brand writes in thirsty, “Look it’s like this, I’m just like the rest, / limping across the city, flying when I can” (57). Sitting at his window, painstakingly revising the form and content of his visions, the city—as seen and felt through the window—becomes a radical site of spiritual interaction and exchange. It is through Clarke’s windows—architectural, corporeal, temporal—that we imagine and ’member the world.

One of Austin Clarke’s earliest poems.

Permissions: William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library