/ CHAPTER 14

The Lessons of Austin Clarke

Sonnet L’Abbé

I met Austin Clarke in late 1996 at the University of Guelph, where he was that year’s writer-in-residence. He didn’t yet have the dreads I would later see him rocking at literary festivals. They had given him an office; two days a week he sat at a desk with his back to the window. I would show up for an appointment and he would wave me in without looking up from what he was doing. Often, he was writing a letter. He wrote in a broad, bold hand that looked to me to be literal calligraphy: he used a cartridge pen with a golden nib with a wide, flat edge against toothy paper. I would slide into the chair and sit there uncertainly, staring at this Real Writer, a product of the Caribbean encounter with British dipsy-doodling. As I waited, the room was silent except for the scritch-scritch of his pen, punctuated occasionally by a slightly longer scrootch, as, with a flourish, he’d put a tail on a “g” or a “y.” It could be ten minutes before he was ready to give me his attention. And even once we started speaking, I could lose him: sometimes, in the middle of our meeting, he would decide he had to call Barry Callaghan. He’d bid me to stay put, pick up the phone, turn toward the window and talk for a squirmingly long time. Maybe he thought he was treating me to a private performance of the verbal bullshit artistry of old-school literary bros.

“Young L’Abbé,” he said to me in one of those meetings, “these literary people are racists!” He said it like he was genuinely surprised that a long, unwillingly entertained suspicion had been confirmed. We were still a few years before The Polished Hoe. He had just won some other recognition, but seemed in that moment to be processing the fact that he knew the people who had given it to him. Austin had been hanging out all along with the people who would give him recognition, now or in the future, or who would withhold it, and he was not optimistic about their capacity to recognize Black excellence.

I showed Austin the fiction and poetry I was writing, telling him I didn’t want to be a “Black writer,” or a “brown writer,” or “an immigrant’s kid writer.” I just wanted to be “a writer.” He nodded. “You are just a writer,” he said. “And you still are what you are.” Like the other older, male mentors to whom I had read my work, he was uninterested in my stories exploring all the sexist microaggressions I had lived by the time I was twenty-two. My poems, however, seemed to hold his attention. He showed a few to Connie Rooke, and shortly thereafter one of my poems was accepted by the Malahat Review. I was floored.

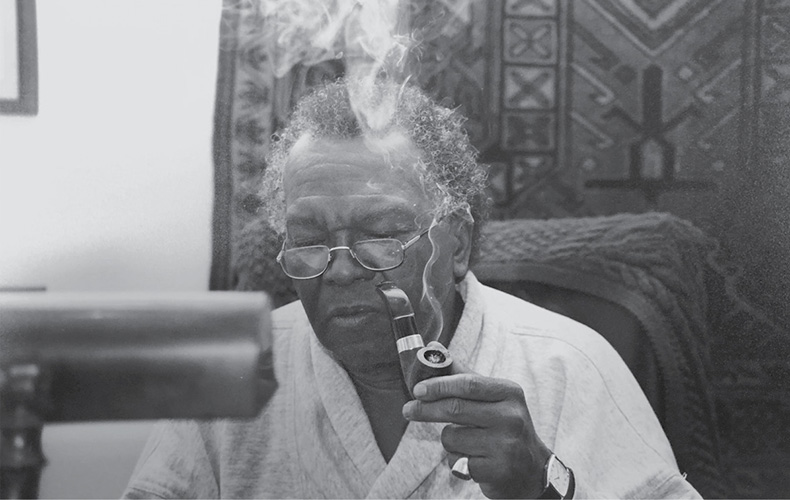

Austin Clarke writing.

Permissions: William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library

What Austin taught me was how much context mattered. I had sent my poems to the Malahat on my own, with a cover letter saying I’d had one piece in Existère, and had been rejected. Now, the same poems (as in, written by the same young person, with the same sensibility, during the same period), made it in, because the right person had introduced me. I had never gotten anything because I knew someone; I wanted merit to be everything. It would be years before I seriously questioned whether male mentors’ estimations of my fiction had more to do with their estimations of my subject matter than my skill. Austin’s help was, in a way, a lesson about Blackness, in the sense that I, too, would have to always negotiate a world where, talent or no, my career would depend heavily on relationships with white folks whose interest in non-white experience was beyond my control, yet who would have the biggest say in whether my work deserved to be published or rewarded.

Austin was working on Pig Tails ’n Breadfruit at the time. Over the fall term, he hosted regular soirées in the suite where he stayed on campus. Austin held court, teaching me and other young writers like Akinsola Jeje, Stephen Wicary, and Joanna Cockerline how to make a proper martini and how to drink quite a few of them. At one of these get-togethers, Austin spent most of the evening in the kitchen, slippers on his feet, an apron over his dress pants and collared shirt. What he was stirring in the deep pot smelled good; he called me over. “Y’ever had cow heel?” he asked. “My aunts talk about cow heel, but no. It’s not really heel, is it?” I asked. He lifted the lid: the thing that bubbled up looked, indeed, like a slice of hoof. I grimaced. “What about souse?” asked Austin. I made another face. “No. And no black pudding with blood in it, either,” I said. “Tchh, man,” said Austin. “What kind o’ Guyanese your mother raising?” He served the cow heel soup to us kids in Guelph, along with healthy doses of gin and vermouth, with a few other dishes that he was testing out for the book. That meal remains, to this day, the only experience of cow heel I’ve ever had. It tasted amazing—spicy, robust, and joyful—infused with the spirit of its cook.