/ CHAPTER 18

Austin Clarke: Defying the Silence, a Life in Letters

John Harewood

“Don’t do muh so!” I can hear Austin’s voice issuing the reprimand, tongue in cheek, from his study as he looks through the window on to Moss Park, which inspired Where the Sun Shines Best, one of the last three books he published. Immediately afterwards, I can hear him adding, “God don’t like ugly.” Those of us who knew him well might justifiably argue that he would have reacted in this way on hearing the news that a special collection was being published in his honour.

I was a junior to Austin at high school in the early fifties and, like most of his contemporaries, admired his outstanding achievement as an athlete when he won the Victor Ludorum trophy for two consecutive years. The idea of being a specialist just in one or two races on the track simply didn’t exist and Austin would in later years look contemptuously at those athletes could perform brilliantly in only one race and spent all of their time training for the grand occasion.

I had seen him run, had witnessed the scene when he received the trophy in one of his years of triumph, but I had never heard him speak. Indeed, I had never heard his voice until he sang the part of King John in the production of 1066 and All That by the Harrison College Dramatic Society in 1952.

You couldn’t miss his rich baritone, resonant with a touch of huskiness as he crooned,

I and Richard played as boys together

Best of friends for many years were we

I was always nervous as a kitten

Richard lionhearted as could be

Unlucky John, always sat upon,

Unlucky John, je ne suis plus bon.

Richard died, I took his crown and jewels

Then, one day when I was forced to flee,

I was washed into the wash at washpool

Then I lost my washing in the sea.

Unlucky John, all my clothes have gone,

Unlucky John, I’ve got nothing on.

I am wondering now, whether in later years, he ever saw the last line as a metaphor for his life, that somehow he was often stripped and laid bare for all to see. And ironically, these recent efforts to celebrate him and his work, however justified, might appear to some of his admirers to be yet another stripping, if not an unmasking. For Austin, despite his very public persona, was a very private person.

He would have said that the first stripping had occurred before he entered Harrison College, when one of its cadet officers humiliated him by removing him from the rank of sergeant major as punishment for breaking camp. The next was administered by the headmaster of the same Harrison College, whose supposed “letter of recommendation” of him as a “transfer from Combermere” suggested that he had no real identity as an authentic college boy.

The feeling of rejection continued two years after his arrival in Canada in 1955. Not at all excited by the politics and economics program in which he had registered at Trinity College in the University of Toronto, he withdrew and, in quick succession, worked as a janitor, security guard, Christmas letter carrier, paint factory worker, sculptor, reporter, and stagehand. Tired of being fired, he decided to become a writer, vowing thereafter “not to work for a black or white boss.”

Austin had grown up in a colonial setting where the presence of a foreign master, paradoxically, was both resented and courted. He had left that milieu when the emergence of a third force in world politics became apparent as formerly colonized peoples were asserting their right to self-determination and demanding a new international order based on human rights. In North America, especially the United States, that demand for change manifested itself in the civil rights movement. Canada was not immune to its influence and Austin was soon attracted.

He participated in the Canadian Apartheid Committee, boycotted South African goods, picketed Loblaw’s supermarkets, wrote columns in the Toronto Telegram and Toronto Star protesting the company’s hiring practices and blatant racism. Very quickly, he began to be described as an “activist,” a word whose negative connotations more frequently cast its bearer as a troublemaker rather than an agent for positive change. So an article he wrote denouncing the discrimination that he had personally suffered between 1955 and the mid-sixties earned him the title of “Canada’s Angriest Black Man” from Maclean’s magazine.

I myself was among those Toronto Blacks who were uncertain as to whether we should be embarrassed or offended by his notoriety. We hailed the publication of his first novel, The Survivors of the Crossing, but thought that it wasn’t about us, the experience we were living. Set in the Caribbean with Rufus as its dubious hero, whose desire for socio-economic change motivated his unsuccessful attempt to lead a rebellion against the established order of “the plantation,” it still evoked some empathy, at least from those of us with Caribbean roots. It signalled the presence of a new voice. We could partly identify with it, but we weren’t willing to accept its bearer as our leader or spokesman. We suspected that he had an alternative agenda.

With increased immigration from the Caribbean, Toronto’s demography changed. However, these new immigrants weren’t being reflected in the country’s literature. Like Austin, they were invisible, although conspicuously present. No other writer was addressing their experience of displacement, racial discrimination, alienation, loneliness, or unemployment. He was determined to make them visible, to give them a voice, and emphasize the significance of their presence.

Except that there was no obvious model in the Canadian literary establishment, nor did he think that Dickens, Chaucer, Eliot, and Shakespeare—with whom he had grown up—could be imported to meet the challenge. Rather, he chose to describe the new social reality by introducing a new way of seeing, through a different lens and a language rich in the sounds, rhythms, colour, smells, and humour of the Caribbean. And so was born the now famous Toronto Trilogy: The Meeting Point (1967), Storm of Fortune (1973), and The Bigger Light (1975), featuring Dots, Bernice, and Boysie.

Under his pen, they are Black immigrants from the Caribbean, but nonetheless, they possess all of the aspirations common to any immigrant, as well as the determination to achieve their dreams despite the occasional racism they suffer because of the colour of their skin. Boysie is the prototype; he has achieved the goals pursued by every immigrant—job security and financial success. Yet, his enjoyment of his new status is jeopardized by an increasing alienation from his wife and the West Indian community, toward which he develops a troubling antipathy. This accounts for his constant uncertainty, his preoccupation with a world of fantasy, and a relentless search for “the bigger light.”

I had seen Austin briefly on the street one day in 1964 when he informed me that he had published his first novel. I met him again shortly after Storm of Fortune appeared. My copy still bears his autograph with the words, “For John Harewood from the homeland with love, Toronto, 7 July, 1973.” He had already persuaded me by letter, in his trademark style of calligraphy, to write for Contrast, the Black community paper of the day. On October 23, 1972, he wrote:

Harewood!

Send some papers fuh we, nuh? And keep in touch, yuh hear. You want to review books for we? Well, ok, buy the kiss-me-arse book, then and write the review. We don’t pay. I working free, so you understand!

This letter was the beginning of our forty-four years of correspondence and a very close friendship. If Clarke’s memoirs and novels give a view of his public voice, his letters communicate another side. After all, here was a man who enjoyed a multi-faceted career, as writer, but also as a diplomat, politician, teacher, professor, and bureaucrat. In the letters, invariably, he is brutally frank, uninhibited, irreverent, and unapologetic, but at the same time charming, humorous, and empathetic. In general, Austin didn’t assign titles to his letters, but he seems to have reserved his strongest opinions and most graphic and colourful language for certain topics, which I have tried to reflect in the excerpts that follow.

Love, Women, and Marriage

1:20 p.m. Wednesday, December 27, 2000,

I here, Harewood, on this nice bank holiday, listening to calypsos from the 1990s and really enjoying them. . . . But there is a reason that I so happy these days, Harewood. Woman. Harewood, when I tell you “woman,” Harewood, um is the first time in my life, that I actually fall in love with a woman. . . . I mean a woman-and-a-half. I never knew love could be so sweet. Man, she have me doing things I never do before in my life. Things that sweet. Things that bring-out the man and that bring-out the woman. The things that true love made of. But more than anything is the peace that she bring into my life. Peace and security and sure-ness. And confidence.

Writing, Other Writers, and Friendship

March 26, 1974,

Man, if I had was to begin life all over again from the beginning, I would cram scientific phrases and be a kiss-me-arse psychiatriss. But to want to be a writer and nobody ain drive some blows in your clothes to mek you one, and you choose that by yourself, man that is suicide of self, man. Writing hard as shite. I just finding that out.

12:45 p.m. April 23, 1988,

And I uses to dream o’ days when I too, couldda be in my barrister silks, and walk with a limp o’ style, always pulling up my trousers, and looking as if I have in rums and talking pure big words and legal phraseologies . . . and hold over the railing and look down ’pon lesser mortals. . . . My dreams did always big dreams. And when I hit ’pon that idea in Proud Empires, at the very beginning o’ the novel, I was real proud, and did in fact, to some degree, writing about my own-own fantasies.

11:06 a.m. January 9, 1997, while writing The Origin of Waves:

If you siddown beside a lake too often, and in particular ’pon a dark night, the only intellectual thing for you to do, is jump in the blasted lake, yuh! Suicide must come in your mind. Um is as if the water is the water you was contain in, when you was in your mother’s womb, and now that you born, and is even a man, the realism of this lake is to suck you back In water, have a compelling force like it want to suck you back in. . . . So, in a sense, it isn’t suicide in the normal sense, but a kind of enforce re-entry inside the womb.

I write the book, yuh! I write the book saying this, but didn’t know what the arse I was saying when I write um. And continuing the metaphor, I see my life as a kiss-me-arse lake.

Regarding More, his last novel, he was more expansive:

The structure of this novel is different from all the rest I have written; and I am trying out a new idea of not making the narrative follow a line that is straight, but one that stops abruptly and then may continue with a flashback . . . and then reconnect with the beginning of the narrative. . . . I have the same feeling of excitement writing this novel, as I had when I was writing The Polished Hoe.

1:00 p.m. December 31, 1985,

Yesterday was a sad day for literature and people who work in literature; Jack McClelland sold his firm; but as you may know by now, he will remain the publisher for at least five years. All the big shots in the whirl of literature were there at the Royal York, in the library room. And once again, I had to say that it is a pity that I am the only black writer who has that profile. . . . And I suspect that since there were so few of us writers, Atwood, Gibson, Berton, and Templeton, invited to that important and significant ceremony, that my stars must be pitching, at last.

2.57 p.m. February 27, 1981, when Andrew Salkey, “one of the pioneers o’ Wessindian Literature,” once visited Toronto with Kamau Brathwaite and Paule Marshall, Clarke was ecstatic:

Braff and Handrew Salkey and Paule Marshall, did here. Man, they get on bad bad bad. Paule Marshall put a reading ’pon de people up at York, that had them bawling fuh murder. And Braff read “Negus” from Masks, with the thing that does go “it, it, it, it is not, it is not, it is not enough to be semi-colon, semi-colony” and Jesus Christ, Harewood, I telling you um was pure po’try and fire and brimstones and rockstones he pelt- bout in that auditorium. Pretty pretty pretty fuh so! . . . Then, Handrew Salkey face the new ball. . . . He slam Naipaul to the boundary for selling out. Plam.

Miscellaneous Concerns

Clearly, he had reached a low point emotionally in the summer of 1996. At 2:19 p.m. on August 26, 1996, he wrote:

I have two dollars and twenty-something cents to my name. Um can’t buy coffee. Um can’t buy a stamp. Um can’t buy a butter-tart. Um can’t buy a return ticket ’pon the subway, in case I want to go down by the lake and jump in; or, if I change my mind concerning the jumping in, crawl-back here. Um can’t buy a beer not even a draff-beer. And um sure can’t buy a pack o’ cigarettes. . . . So, I have to wait and see if there is a God, and if he have any mercy ’pon writers. Sometimes, I don’t think so. This is one Monday morning when I know-so.

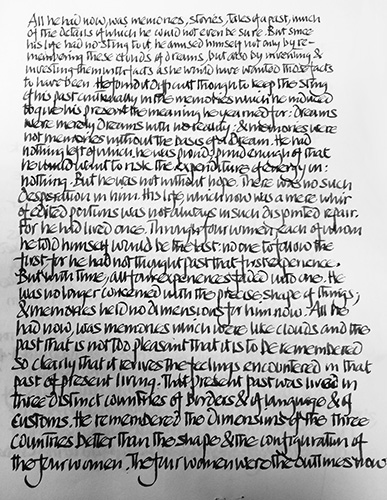

Austin Clarke diary entry.

Permissions: The Estate of Austin Clarke

And, in the summer of 1997, at the very moment when the first tribute to him was organized at Toronto’s Harbourfront and he was thinking about attempting a new start in Italy, he wrote at 11:16 a.m. on July 21:

I feel like a new immigrand, just land, and facing this big city, not knowing where the next kiss-me-arse meal going come from. And all this realism in the midst of praise! . . . I can’t even walk and lick-bout two brown pennies inside my fob-pocket. I asking myself, what this mean? I asking myself, I do somebody something, that God like he forget me? I asking myself, if I in the middle of a cycle o’ blows, that have to run its revolution before I could come up for breath, before I drown? I asking myself, if this is the end? I asking myself, if I on the cusp or the crust o’ something more bigger than me-myself?

On meeting the Queen. 12:40 p.m. July 29, 2004,

Man, when I enter Buckennam that morning in March, the eighth at 12:40 p.m., the exact hour that I happen to address this letter to you . . . I never, in my wildest dreams thought that me and Her Majesty would one day, in Buckennam, shake hands; and that she would smile in my face and axe me, “And what tie are you wearing, Mr. Clarke?” When I tell she um was Harsun College, in Barbados, she eyes light up, and she tell me, “Oh yes! My trainer is a Barbadian, Stoute. I think his father was a Commissioner of Police in Barbados. . . . And that cause me to chirp-in and tell bout my step-father; bout 434 Luke driving the Commissioner car; bout Stoutie youngest brother being the Dean of my cathedral church . . . and thing and thing . . . and we end up like two old friends, discussing the advantages and multiple disadvantages of the computer. . . . Harewood, when I tell you that it was sweet, sweet, sweet, then . . .

On his lifelong love of cooking. 3:37 p.m., November 20, 2004,

You might very well become distraught when I tell you what I am doing at this time. I am sipping a cold, dry, very dry Bombay Sapphire martini, made by my own two hands, with a thick slice of the skin from a grapefruit; in a very chilled glass; and eating slices of French brie cheese.

And guess what? Don’t kill me when I confess what I doing, in addition to sipping a Bombay Sapphire, and eating a little good cheese. I cooking . . . Basmati rice and Jamaica red beans, boiled down in some juicy pig tails; with a gravy and a sauce of beef short ribs that I buy from the Sin-Lawrence Market; braizing in a gravy with red wine, onions, fresh tomato, Jamaican jerk seasoning, and the usual condiments. My God, Harewood, I too-glad you ain’t here, so I have to share this “Bittle” with you, don’t mind you is my best friend! Some things friendship can’t come betwixt-and-between, and don’t mind the “longtitude” and the “latitude” o’ that friendship.

The Sessions

We called them sessions! Informal get-togethers! There might have been two of us, three of us, or four of us. A session was held in Toronto, at 62 McGill or 150 Shuter; in Ottawa, at Carl Taylor’s, Gregg Edwards’s, Charles Skeete’s, or my place. A session might begin at the Grand Hotel, but, while that venue was highly favoured, it was really a warm-up. The real thing occurred at a house, at no fixed time, and it was understood that it could continue indefinitely. Only three components were predictable: conversation, food, and drink.

Sometimes, I would call ahead to let Austin know that I was coming to town or he would inform me, by letter, that he would be coming to Ottawa to be a part of the jury to select a winner for the Governor General’s Award for fiction, or for some other assignment. Alternatively, I would call from Union Station when I arrived. If he happened to be at home, which was often the case, Austin would invite me to come over. His hospitality would start as soon as I entered the house. He would offer a beverage of choice or tea and something to eat. We would talk, perhaps about a current news story, what was happening in our lives, or what he was working on.

On occasion, I would stay overnight, bunking on the sofa on the second floor, amidst shelves of books with Miles Davis or John Coltrane on in the background, while Clarke sat working in his study until dawn, often preferring his faithful Bertha, an old IBM typewriter, to his laptop. Shortly after he returned from a reading trip to Australia in 2004, we met in the Grand Hotel, his watering hole. As usual, he was the last to leave and, to quote him, “We closed it.”

We then retired to 150 Shuter and held session, sipping tea as he recalled the warm reception given to him by some white Bajans who had migrated “Down Under.” He was pleasantly surprised by their familiarity with his work.

Morning broke, whereupon he suggested that we return to the Grand for breakfast, still clothed as we had been the previous evening. This was unusual, for after a session like that, he would normally prepare breakfast as he did once when I overnighted. I had come down to attend “Honouring Austin Clarke,” an event organized by the Caribbean Consular Corps and the Caribbean Canadian Literary Expo at the Toronto Reference Library. On that occasion, he offered me his bedroom in the attic while he toiled through the night working on a short story.

I last saw him on November 1, 2015. The Toronto International Authors’ Festival had included a tribute to him to coincide with the publication of ’Membering. He was too weak to attend, but after the proceedings, a number of us trooped over to 150 Shuter for a session. The protocol was familiar. Much to eat and drink. Lively conversation. He was quiet, sometimes amused, ever attentive.

I increased calling on my return to Ottawa but reached him only twice in the New Year. On the morning of June 27, 2016, his daughter, Darcy, called to let me know of his passing. She asked me to be one of the pallbearers.

8:09 a.m. January 12, 1996:

But Harewood!

And talking ’bout time, why am I at this early hour this morning spenning time ’pon you, you brute-beast who negleck me all them months when you was mekking hay in hay-loffs and haywoods and laughing? Because we is friends. And was friends from long. And, gorblummuh, going- remain likewise till I sing “The Day Thou Gavest” over you or you sing The Day Thou Gavest over me, meaning till one o’ we dead. Or, in other words, lifelong friends.

“The Day Thou Gavest” was the second hymn at the funeral service held for Austin Ardinel Chesterfield “Tom” Clarke at the Cathedral Church of St. James in Toronto, on Friday, July 8, 2016.

I sat behind Loretta and Darcy, and beside Jordan and her husband. I sang.