/ CHAPTER 21

There Will Never Be Another Austin Clarke

Patrick Crean

Patrick Crean is one of Canadian literature’s best-known and most respected editors. From his beginnings monitoring the slush pile at McClelland and Stewart, he has gone on to edit and publish a number of award-winning novels, including three Giller Prize winners: Esi Edugyan’s Half-Blood Blues and Washington Black and Austin Clarke’s The Polished Hoe. His relationship with Clarke stretches back to the 1970s, when he edited The Prime Minister, and Crean has had a lengthy professional and personal relationship with Clarke. On a Bloor Street patio during the summer of 2019, Paul Barrett and Patrick Crean sat down to discuss editing Austin Clarke.

Clarke’s Black Power Conservatism

I first met Austin in 1976 when I was living on Brunswick Avenue in Toronto and Austin and his family lived just north of me, near Jan Sibelius Park. My first wife loved jazz and used to hang out at the First Floor Club, had met Austin, and eventually hooked us up. This was when I was with General Publishing, the forerunner of the Stoddart imprint and we signed Austin to write The Prime Minister. I remember it was during the Black Power era and he was, of course, involved in that with his activism, appearing on television and, among other things, interviewing Malcolm X in New York for the CBC.

There was some sense of that in the book: a kind of Black Power satire of Caribbean politics. Part of the plot of The Prime Minister came out of Austin’s appointment as the head of the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. His tenure was not only short but from what he told me, actually dangerous; he spoke out against corruption and he was pretty disliked at that time on the island and there was talk of guns. This feeling made it into The Prime Minister and it led to the book being banned in Barbados until quite recently.

This was my first introduction to Austin. I was twenty-six at the time, working with this Black intellectual who was, in many ways, terrifying to be around because he would drop into these silences and just smoke his pipe and stare for long minutes, sometimes even an hour, wordlessly contemplating my edits, or just sitting with me wordlessly. Once he sat for an entire hour in silence over lunch at the Park Plaza because he felt he was not getting enough publicity for his book. He was like an African king. Imperial. Imperious.

There was this paradoxical sense in everything that Austin did. Was he a progressive or a conservative? He spent some time working for the Ontario Board of Censors. But he also worked for the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada after that. Then there was the launch for The Prime Minister at the Underground Railroad restaurant, which was attended by a number of Progressive Conservative politicians: Bill Davis, Roy McMurtry, and a number of other members of the Ontario PC Party. That was Austin: Conservative politicians attending his book launch alongside members of the Black Power community. Austin ran for a Conservative nomination (and didn’t get it) and also wrote for the Black newspapers; he might have even liked Margaret Thatcher! I could always imagine Austin in the House of Commons in a Churchillian manner. He was an incredibly articulate and eloquent public speaker with his slow Barbadian cadence. But still: Who was he? What were his politics? Where did he really fit?

That was also my first introduction to the challenge of selling Black literature in a predominantly white Canada, and Austin’s work more generally. I think today his work is neglected and overlooked. And yet, I am certain he must be an influence on today’s Black writers. I am sure there was inspiration there for Dionne Brand, Lawrence Hill, or Esi Edugyan and others. He is the grandfather of Black Canadian letters. Can you think of anyone before him?

After The Prime Minister we had something of a breakup and didn’t work together again for over twenty years. Austin moved around to a number of publishers and by all accounts was notoriously hard to work with. At the same time, though, the celebrated publisher Jack McClelland is quoted as saying that “Austin is one of our greats.” I think Austin drove everyone crazy at M&S, but Jack really thought very highly of his writing and talent.

We really didn’t have any contact in the years after The Prime Minister but in the very early 2000s we got back together. His agent had gotten into some kind of dispute with McClelland and Stewart and Austin felt that he couldn’t work with M&S any longer. So he approached me, completely out of the blue, and said, I’ve got this book, would you be interested? It was called The Polished Hoe.

Editing The Polished Hoe

I was just starting out with this brand new imprint, the opportunity of my career, at Thomas Allen. The first thing you worry about with a new imprint is credibilty: so getting Austin on board was an absolute gift. Because of his already considerable literary reputation, he was our ticket to getting some publishing cred. So we began to work on The Polished Hoe. And what he first delivered to me was a gigantic, enormous, huge manuscript, over fifteen hundred pages. It was one of the most fascinating and challenging edits I’ve ever done.

I was lucky because I was able to head up north with that manuscript and repair to an island in Georgian Bay, by myself, for ten days. There was no electricity, no television, no Internet, so the quality of my attention was exceptionally focused; I lived with this novel for ten solid days with no interruption in complete solitude.

I remember to this day reading into the manuscript on that island and saying aloud to myself: “Holy fuck! This is a masterpiece!” The hairs were going up on my neck. It happened during one of the scenes in the book about the hurricane and as I was reading this, I just knew it was a masterpiece. I can remember that vividly. The feeling is still with me.

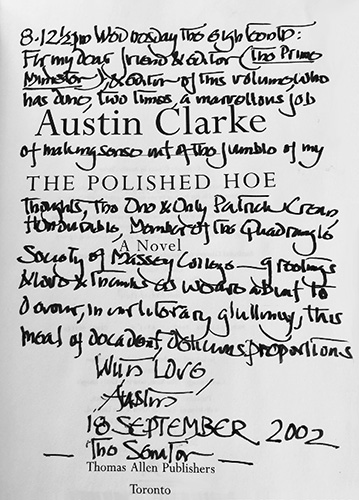

Patrick Crean’s copy of The Polished Hoe with dedication from Austin Clarke.

Permissions: Patrick Crean

Yet, despite that feeling, the manuscript was uneven and terribly lumpy, repetitive, and at times overwrought. It was a huge, glorious mess. So I was up there for ten days, isolated and editing, working intensely to turn this giant pile of paper into something that hung together: making notes, and crossing out entire pages and sections. It helped that he wrote triple spaced with huge margins that invited you to really edit it.

I must add a lovely detail here: Austin had a beautiful and distinct hand. He wrote with an ink fountain pen and his notes would fill the triple space; sometimes with comments; sometimes with revisions. We would write back and forth that way, as well as me giving him a general editorial note.

When I returned to Toronto, we met at Massey College, and he just stared at me in that familiar, silent way. Austin could read body language as well as he could read the editorial notes; he had an incredible sense of intuition around his craft. I know this sounds completely counterintuitive, but when we met he would pick up on what was wrong with the narrative without even looking at my notes. In that respect he was actually quite wonderful to work with—of course there were challenges, but he was such a pro. He didn’t go off and grumble; well, he might sulk a bit, but in the end he would understand that there was work to be done. That was the situation with The Polished Hoe: I remember sitting down at Massey College with him, praising the manuscript, but also reporting on my first round of edits and the work ahead. So he left, taking the manuscript with him.

Then the manuscript came back from Austin. He had put back all of the parts I had cut out! We went back and forth with this two or three times. Finally, he agreed that maybe I had a point and reinstated most of the cuts. For me, this was as much a matter of wrestling with the author as it was about my job representing the reader. When one is lost in the narrative, because things have gotten too abstract, or the plot is too complicated, the challenge is to pull it all together in some coherent manner, while at the same time making sure the author has realized his intent—and not imposing oneself on the narrative.

I will admit, though, that when I worked with Austin I did worry about a white editor editing a Black sensibility. And I don’t mean just the content of the narrative, but more the tonality of his prose and what I think of as the music of that book: there are subtle layers of African-American and Caribbean rhythms in The Polished Hoe. You need to listen carefully. I have always loved jazz. And reading Austin is reading jazz. So what I try to do as an editor is to approach text as though it is musical score. In my first reading, I’m not using my intellect as much as I am listening; I want to allow the text to work on me through its rhythms. And that really required great delicacy and attention because this is not my culture. I have to admit that he really startled me once when he said in jest after a particularly intense edit that I was a damn slave-driver!

There were really only two major disagreements about the editing of the book. The first concern I had was about the character of Bellfeels, the cruel plantation owner. In the early drafts of the novel Bellfeels was too singularly evil. I insisted that I didn’t think he could write a character that evil and be believable on the page. So Austin allowed that Bellfeels needed some more complexity as a character.

The second concern, and perhaps the strangest part of that editing process, was our disagreement over the ending of the book. We were engaged in that struggle right up to the deadline. Weeks before the book was set to go to the printer, Austin was insisting that the book should end with Sargeant raping Mary-Mathilda.

I completely disagreed; I said, “Austin, that’s totally out of character. It doesn’t work, it comes out of nowhere, it would simply kill the book.” There’s no doubt, of course, that Sargeant had a crush on Mary Mathilda, and I could imagine him coming onto her or kissing her, but violently so? Raping her? For me, it simply didn’t ring true given how these characters behaved throughout the the novel. Thankfully, Austin came around to see my perspective.

On The Polished Hoe Being Shortlisted for the Giller

When the book went off to the critics, the reviews were spectacular: he’d hit a home run. Then we were all gobsmacked when the book was shortlisted for the Giller. There was no longlist in those days; he was just immediately shortlisted.

Part of my surprise was that in spite of the inherent brilliance of the novel, Clarke’s writing can be really challenging; The Polished Hoe was a polarizing and challenging book: it takes place in one night; it has a Joycean movement to it. It is circular, subterranean, subtle, and works on many levels, but is the kind of novel that rewards the more you work at it. The other part of the surprise seeing him get shortlisted for the Giller is that Austin’s work had to that point been somewhat overlooked. That was partially because of the complexity of the work and partially because he wasn’t exactly the most popular person in the world. He had alienated too many people in his life. Of course, a lot of great writers are ignored or not recognized, but this was made more acute because race played a significant role in the reception of Austin’s writing.

Austin, very wisely, said at our Giller gala table beforehand: “Whatever happens tonight, there shall be no tears.” The tension in that room was intense, and when he won it was absolutely incredible. When his name was announced, and they said, “The winner of the 2002 Giller Prize is Austin Clarke,” there was an audible intake of breath in the room and this undercurrent of “Woah, how could this be?” We, of course, were thrilled; but everyone in the room thought the winner was going to be Carol Shields—she was dying of cancer—and the audience wasn’t prepared for Austin to win. Carol Shields was definitely the popular choice that year.

When he won it was, of course, fantastic, but also a little bit bittersweet and odd because Austin delivered a bold speech that was eloquent, but it was also aggressive and even gloating. He talked about conquering and looting; there was a sense of “I have won” and “Here I am, a Black man in a sea of white faces.” It was certainly a moment of triumph for him. Once again, he broke the mould.

Winning the Giller was a career-changing moment. He had money, he did a huge renovation on his house, he celebrated, he was a king in a castle. During that Giller glow of a year or two, we were really rocking. We both thanked each other for what we’d done for one another. He was generous with me and acknowledged his editor publically, the amount of work that had gone into the writing and editing. We were compadres. At the same time, I’m not sure he behaved terribly well: Austin became orgueilleux, he became arrogant, so it made things difficult in that way too.

After the Giller he had said to the press that he was one of the few writers in Canada who could live off his earnings. This was true, but it rapidly became untrue. He really celebrated his win and while he certainly made good money from The Polished Hoe, it didn’t last forever.

That’s one of the sad things about writing in Canada. When André Alexis accepted his Giller, he said, “Now I’m even.” The win simply pulled him out of debt and brought his balance up to zero. Michael Redhill said he had five dollars in his bank account the day before winning. That’s simply the state of things in Canada. Austin, of course, relished his victory and his accolades, but eventually it came time to get back to work.

Visiting Barbados

I had some insight into Austin’s life when, just after The Polished Hoe had come out, I had the good fortune to visit Barbados and stay with friends. My wife, the novelist Susan Swan, and I visited Austin’s childhood neighbourhood: we went to St. Matthias Church, where he had gone to Sunday services with his mother, and we went to Harrison College to sit on the benches in the Great Hall. It may seem obvious, but the journey this man took from real poverty to celebrating his victory at the Gillers is pretty incredible. I was so struck by this: he went from poverty to the equivalent of Upper Canada College in Barbados to the University of Toronto to winning the Giller Prize. He was very proud of that.

As much as Austin writes about race, he’s also writing about class. And if you think about it, in Canadian literature, how many working class writers do we really have? The Canadian literary community can be quite an insular establishment along both racial and class lines. Perhaps that also had something to do with his sense of alienation?

I mean, he wore his Harrison College jacket when he went to meet the Queen. That was certainly one of the highlights of his career. He told me that he would ask her for a pardon for having a written a book entitled Growing Up Stupid Under the Union Jack. But apparently they had a good chat, they both knew someone in common in Barbados.

To understand Austin’s perspective, we have to think of him arriving here, in the middle of winter in the 1950s, to attend Trinity College in a very white and pretty racist society. Without a shadow of a doubt, Austin Clarke broke the mould in this country, I mean in particular the white domination of creative writing.

Austin was raised with dignity and pride in what is mostly a homogenous Black society of Barbados, then arrives in Canada, and finds himself in a prejudiced and somewhat backwater Canadian culture that’s only beginning to find itself. He would tell me about the racism he experienced—the question he would get asked again and again: “Who do you think you are?” He would try to do basic things like change his train ticket and they’d give him a hard time. Simply because he was Black.

We see this continuing today. But now more Black writers are pushing back, raising awareness and fighting racism. For example, with Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black, in some respects she’s taking on white people who are sympathetic to Black people but in fact are more concerned about the moral stain on themselves than they are about the condition of Black people. For so many white people the response to racism is “I’m so sorry, but I’m a progressive, I’m not at all racist; I’m a liberal.” Austin then, and Esi now, among other Black writers, are showing the limitations of that white, liberal perspective.

On Publishing More

After celebrating the Giller for some time, I began to ask him about his next work. He had been talking about this novel More that he’d worked on for years and was hoping to return to. In the 1970s he had embarked on a version of the novel, about a woman who had worked for a Jewish family in Forest Hill. Austin always had a bitterness and anger toward Forest Hill and rich Jewish people.

When More came to me it was an unfinished novel that centred on the Domestic Scheme, which he was, of course, very taken up with. This is the program that was arranged between the Canadian government and governments in the West Indies that has come under heavy criticism for being the next thing to slave labour.

So what started as something of a reflection on the relationship between Black people in Toronto and rich Jewish families in Forest Hill became more of a meditation on Black oppression in Canada alongside the experience of generational disconnect. More was an urban, Canadian novel as opposed to the wider canvas of The Polished Hoe, which we can see as a metaphor for the broader history of slavery in the Caribbean.

I will say that, at the height of his powers, Austin was a world-beater. He was an extraordinary writer when he was in top form. But More, in some ways, reflects a decline in his powers. That said, this may have to do with its lengthy publication history. More was something else back in the early drafts in the 1970s, and it morphed into what it is now.

The beginning of More required a huge line edit: he and I really wrestled over the first half of the book. The prose was weaker than The Polished Hoe and it didn’t have the same tensility or robustness. When it was released, I remember feeling hopeful when he was longlisted for the Giller and then dashed when he didn’t get shortlisted. Yet now when I reflect on it, while I do think it is a good novel, it certainly isn’t a masterpiece. It did, however, win the Toronto Book Award that year.

Nevertheless, Austin’s decline continued in his later years and then I turned down some material that really was not publishable. This affected our relationship at the end of his life; particularly so because his powers were fading. He was working on a final novel called So What? after the Miles Davis piece, and it just didn’t work. As an editor, I think there’s an underlying quality of life experience (or not) that imbues a writer’s line: the wisdom, life experience, and maturity (or lack thereof) of that particular artist arising from his or her unconscious. Austin’s later work had a very muddy and disconnected quality.

At the very end, he asked me to look at some new short stories. But they were simply not good enough—and I could not see how any amount of work and editing could improve them—and I turned them down. They did not have the power of his earlier work. He took my rejection of those stories very personally and felt that I’d betrayed him—but sadly, the fact was these stories were just not up to the quality of his previous work.

Our relationship really suffered because of this: I had also commissioned him to write a memoir (’Membering) but the draft was so abstract and vague and with so much disconnected riffing on various topics that I couldn’t imagine many people being interested in it. Instead of writing clearly and honestly about his life, he chose innuendo, obscure code, abstraction, vagueness, and a meandering potpourri of half-baked memories.

But when a not dissimilar text that puported to be a memoir finally came out with another press what really struck me was the extent to which he was truly the unreliable narrator of his own life. It wasn’t just his characters, Idora and Mary-Mathilda, but Austin himself who was paradoxical and unreliable. It was quite astonishing how he could make up things about his own life or avoid difficult truths.

On Their Friendship

In spite of all this, there was great fondness between us. I loved the man; I still love him. He certainly pissed me off at times. He made me very angry. But there was also something I loved about him. He’d come to my house on Brunswick, and he’d be so comfortable hanging out there. We’d go and have dinner together and he’d confide in me about everything happening with him. His loves, his concerns, his hopes and dreams.

Even though Austin could be a rascal, engaged in all kinds of misbehaviour toward his friends and family, I still had time for him I think because of those heady, exciting literary and publishing moments we shared. I was very honoured to be one of the pallbearers at his funeral, celebrating his life at the same church that he wrote about in More.

And yet, I felt sad at the end because it seemed that he was signalling he was disappointed in me. Sure, I thought he was being unfair, but he expected that I’d publish anything that he produced and that was unreasonable. His decline was very sad to witness.

But what I want to remember are those moments like the one on the island in Georgian Bay with Austin’s masterpiece and the language and music of the text and the hurricane wafting over me: in that moment, I felt tremendously excited. If an editor has the luck to be able to work on a book like that, you can get this crazy feeling that impels you to want to run out on the street and tell everybody about how good the book is. Austin really was blessed as a great writer, able to conjure and produce brilliant material. I consider myself exceptionally lucky to have known him and to have had a working relationship, as well as a friendship, with him. There certainly will never be another Austin Clarke. As Man!