/ CHAPTER 30

Recognition

David Chariandy

I met him for the first time at an academic function, a downtown bar of the vaguely hip sort preferred by graduate students and faculty: local beer, alternative music, standing circles of subdued professional conversation. And when Rinaldo walked him into our midst, I wondered how this would play out. Here was Austin Clarke himself, debonair in his sports jacket and the bright tongue of a pocket square. I was wearing a black T-shirt earnestly tight; and when Rinaldo privately introduced me to the author, I got a nod but also a subtle look of disapproval. Austin afterwards made little effort to engage with me or any of the other “academicians” in our small group. One was doing most of the talking: about teaching, about theory, about celebrated new books. Austin remained quiet, pointedly so, until the talker deigned to address the newcomer. “I’m sorry,” the talker began, “I don’t believe I know who you are.” “And why not?” Austin replied.

There was a lot of Austin in that reply, a lot of his insistent pride, and a lot, too, about the long and entirely unconcluded struggle faced by a generation of Black writers in securing due recognition in Canada, even among literary experts. When I met him in that bar, Austin was in fact no stranger to the academy. He had taught at Yale and Duke and had contributed in multiple ways to Black and Caribbean studies throughout the world. He was of course the author of many important and pivotal books, including The Meeting Point, the first novel to substantially evoke Black life in Canada. The Meeting Point focuses on a circle of Black domestic workers who, in the fifties and early sixties, were able to bypass Canadian immigration restrictions against people from the non-white world through the “West Indian Domestic Scheme.” At one point in the novel, a worker named Bernice witnesses a protest on the Toronto streets against racial intolerance, but tells her friend Dots, “[T]hese niggers in Canada! Well, they don’t know how lucky they are!” (305). Bernice continues to explain to Dots, also a domestic worker, that “this is Canada, dear, not America. You and me, we is West Indians, not American Negroes. We are not in that mess” (306). However, at the end of the novel, Bernice witnesses the brutal beating of a Black friend by police, experiencing the scene as “too real; and too much of a dream at the same time. The brutality and the violence” (341). And when Dots eventually sees this same friend in hospital, she exclaims, “I never knew that this place was so blasted cruel” (346).

I’d say that The Meeting Point stages a “recognition” markedly different from the “politics of recognition” as imagined by the philosopher Charles Taylor, wherein minorities appeal for judiciously measured attention from the state through institutionally legible enunciations of identity. But my first meeting with Austin presses me to focus on a separate if related matter—how certain writers, evoking certain issues in certain ways, can so easily go unrecognized. For me, the most striking cases here are of Black women like M. NourbeSe Philip, who in her own words risked being “disappeared”; or else the even more extreme case of Claire Harris, who did quite literally seem to vanish from Canadian letters, and whose poetic legacy is in need of due appreciation and custodianship. But I’m also now thinking of Sam Selvon, that indisputable giant of Caribbean literature and “nation language” for whom Austin wrote a book-long tribute, but whom, after moving to Canada and writing several books, was completely ignored, receiving not a single review here. For a while, Selvon supported himself by working as a janitor at the University of Calgary—an adequate symbol, one suspects, of the enduring relationship of the First World academy to the labour, cultural and otherwise, of the global South. The struggle for true recognition continues today among a new generation of Black and BIPOC writers who have found astonishingly innovative ways to write and share their works, but who must also confront unparalleled contractions and crises in traditional publishing, as well as steadily declining funding, institutional support, and venues for the informed discussion of their work. There remains the old problem of those who dismiss all writing they either naively or cynically deem “political.” But newly amplified, today, is the problem of those with belated, voyeuristic, and ultimately passing curiosity in “the political” who refuse to treat Black writers as complex and disciplined artists and intellectuals.

But I think that in my first meeting with Austin in that bar there was a whole different sort of recognition, if that’s how to describe it. For what word do we use to describe those forms of connection and intimacy that occur in Black life and potentially also among people of companion experiences and sensibilities—those experiences and calculations carried in gesture and voice, “in words and not in words,” at turns covertly signalled and boldly declared? I don’t know when exactly it was that I told Austin that my own mother had been of that generation of Black domestic workers he decided to write about. I know it wasn’t upon our first meeting at that bar, in that particular air of knowing and ignorance. But it was nevertheless in that moment when Austin and I began connecting, my tight T-shirt notwithstanding. He did, most certainly, support my work, but here, too, there is something to tell. Despite his best efforts at the very height of his career, Austin simply couldn’t convince the mainstream literary establishment of whatever potential he saw in me. And it was in fact through the collective effort of younger and less “connected” authors like Wayde Compton, Ashok Mathur, and Larissa Lai, as well as Brian Lam and Robert Ballantyne of the fiercely independent Arsenal Pulp Press, that my first book was eventually published. Austin’s gift to me was not a door to “the establishment” or “literary celebrity” swung widely open, for he himself had limited access to these things. Instead, he offered me things infinitely more meaningful—writerly friendship and a living link with a powerful tradition.

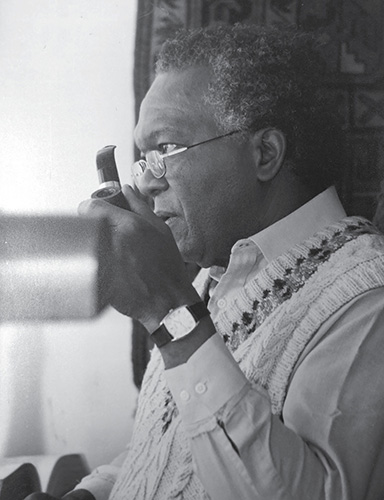

Austin Clarke.

Permissions: William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections, McMaster University Library

In his last years, Austin would often ask about the next novel I was writing, the one he hoped would experience the “sophomore” success he himself never enjoyed. He never lived to see this novel published; and when I dedicated it to him posthumously, I understood the gesture to be at once sincere and complex. A poet I know—a man, I’d point out—once insisted that dedications or mottos are never homages ordinarily imagined, but rather something like a declaration of war. And I get that to some extent. Stylistically, Austin and I were very different, both in dress and also on the page. We were Black men with Caribbean roots; but his were Bajan and mine were what he wryly called “Trickidadian.” Austin showed me love, but he sometimes expressed impatience with my doubts and moments of quiet —“Stop acting like the young men in your books,” he once complained. He was at one point reputed to be “the angriest Black man in Canada,” but his cultural politics were often as challenging to parse as some of his most gorgeously baroque sentences, being either brilliantly anarchic or else outright contradictory: socialist in one breath and candidate for the Progressive Conservative Party in another. And behind it all were our generational differences: the fact that he was “the immigrant” of that postwar group of Caribbean émigrés who sought possibility here, but who learned in new terms their Blackness; and the fact that I was of the rising numbers of the “the born here,” narrated lifelong by the nation of our birth as unwanted outsiders, but knowing intimately no other space, and needing some imaginative alternative, some greater story of being. Yet this generational difference seemed to connect Austin and I the strongest. In the novels we each wrote during the years of our friendship, I kept imagining that we were reaching out to each other. His Bernice and Dots echoing my Adele and Ruth. His BJ the family of my Michael and Francis. Austin taught me that kinship is never a sameness but a loving seeing across distance.

I don’t recall Austin and I ever again attending another academic function. When we met, it was in bars of his choosing—noisy, upscale places of wealth and transit where upon entering you would quickly spot him. And I most often remember seating myself slightly apart from the man, sometimes across a table, or most often on adjacent angles of a cornered bar—“on the diagonal,” as Dionne Brand once put it—which always seemed Austin’s favorite way to sit and drink, and perhaps his chosen way to live. Rinaldo was always with us, for he remained until the end Austin’s closest confidant, the most intimate sharer of his jokes and tales and brilliance, and Abdi was there too, and in the best moments Dionne and Leslie. In his last months of declining health, Austin abandoned jackets for more comfortable clothes, but he was always stylish, his dreads magnificent. I still see him like that, speaking his magic, or else quiet and regal in the din of conversation about us. He’s working on his third martini, and when our eyes meet he smiles and lifts his glass.