CHAPTER 7

EMBEDDING ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SCIENCE INSTRUCTION IN ENGINEERING DESIGN PROBLEM SOLVING

Kristen Wendell,1 Amber Kendall,2 Merredith Portsmore, 2 Christopher G. Wright,3 Linda Jarvin,2 and Chris Rogers2

University of Massachusetts Boston, 2Tufts University, 3University of Tennessee Knoxville

ABSTRACT

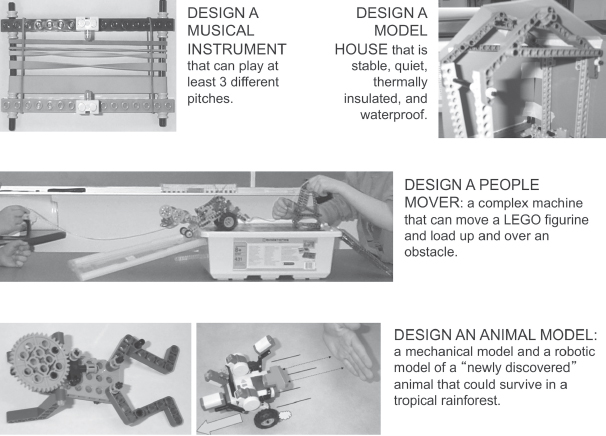

One approach to including engineering in elementary education is to invite students and teachers to explore design prototypes as objects of scientific inquiry. To investigate this approach, we developed and studied the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum, which poses overarching engineering design problems as contexts for exploring science concepts. Our elementary school science curriculum reflects the theoretical perspectives of situated and distributed cognition and draws on the Learning by Design approach to middle school science. In the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum, four units of instruction address the science domains of sound, material properties, animal adaptations, and simple machines as they challenge third- and fourth-grade students to design and construct musical instruments, model houses, robotic animals, and people mover devices. Each unit scaffolds student work with an engineering journal and makes use of LEGO construction elements for prototyping solutions. The units were enacted in over 30 third- and fourth-grade classrooms, where we collected a large corpus of data from teachers and students. In this chapter we triangulate multiple forms of evidence to build the case that science learning can occur in the context of engineering design in the elementary classroom. The evidence includes clinical interviews with students, paper-and-pencil content knowledge tests, student engineering journals, classroom video, and teacher feedback. Our analyses of these data reveal change in both science knowledge and practices during engineering design–based science units. We conclude the chapter by considering some of the challenges associated with enacting engineering design–based curricula and by arguing that the potential benefits outweigh the costs.

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, we consider the strategies and findings of our four-year exploration of embedding elementary school science instruction within engineering design challenges. In a collaboration of science education researchers, assessment specialists, and over 30 third- and fourth-grade teachers, we have developed and investigated four science curriculum units that pose overarching engineering design problems as contexts for exploring science concepts. These units make use of interlocking LEGO construction elements for prototyping solutions, and they invite students and teachers to explore design prototypes as objects of scientific inquiry.

Our aim in this chapter is to use multiple forms of evidence to build the case that science learning can occur in the context of engineering design in the elementary classroom. Thus our guiding question is, what evidence can we find of students learning science through engineering activity?

To begin the chapter, we review our rationale for using engineering design as a context for science education, and we clarify why we have been particularly interested in the elementary school level. We then move on to describe our approach to developing and researching engineering design–based science curricula. This includes brief snapshots of our four curriculum units: Design a Musical Instrument on sound, Design a Model House on material properties, Design an Animal Model on animal adaptations, and Design a People Mover on simple machines.

After this introduction to the Science through LEGO Engineering program, we address our guiding question with evidence that we believe demonstrates students’ science learning. First we look at evidence from pre/post instruments: students’ scores and sample responses on paper-and-pencil science content tests, and students’ thinking revealed in clinical interviews. Then we turn to evidence gathered during lesson enactment: students’ oral expression in whole-class discussion and students’ work in their journals.

The final form of evidence that we present features teachers’ perspectives on engineering design–based science curricula. We share information gathered from a focus group with teachers.

We conclude the chapter by considering some of the special challenges associated with enacting engineering design–based curricula and by arguing that the potential benefits outweigh the possible costs.

THE SCIENCE THROUGH LEGO ENGINEERING PROGRAM

Theoretical and empirical basis

The Science through LEGO Engineering approach to incorporating engineering design problems into elementary school science instruction reflects the theoretical perspectives of situated and distributed cognition, and it also draws heavily upon the Learning by Design approach to middle school science (Kolodner, 2006). Other previous teaching experiments, including those of Roth (1996, 2001), Penner et al. (1997, 1998), Grigorenko, Jarvin, and Sternberg (2002), Sadler et al. (2000), and Krajcik and Blumenfeld (2006), also influenced our curriculum development work.

As Walkington and her colleagues (this volume) also note, the theoretical perspective of situated cognition lends support to the notion that engineering design problems can foster scientific (and mathematical) learning. Consistent with Vygotsky’s (1962) insistence on the sociocultural nature of learning, the situated cognition view asserts that one’s cognition is embedded in, and inseparable from, one’s situation and activity in a community of practice. In other words, concepts, activity, and culture are entangled, and meaningful learning requires this triad of elements. From a situated cognition perspective (e.g., Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Lave & Wenger, 1991), we can describe engineering design as a sociocultural activity that situates the use of science concepts and renders them meaningful.

The theory of distributed cognition (e.g., Hutchins, 1995) also speaks to the role that engineering design may be able to play in science learning. Bell and Winn (2000) define distributed cognition as a person’s individual cognitive acts plus the augmentation of other people, cultural tools, and external devices. From this perspective, we propose that several components of engineering design can “augment” the designer’s cognition: design teammates and coaches (the people), design plans (the cultural tools), and design prototypes (the external devices). These aspects of engineering design can support thinking about science because they can provide multiple means for the representation of science ideas. The process of representing one’s ideas can serve to change one’s understanding (Brizuela & Earnest, 2008). During engineering design activity, a student can represent his or her science ideas in conversation with other designers, through written and pictorial plans, and via tangible design prototypes. This is one way engineering design may support a student’s capacity for science learning.

Despite this theoretical promise, the research community is just beginning to understand how the design–based science approach affects young students’ learning of concepts and practices specific to particular domains of science. While many studies have examined how secondary students engage in science through design problems (Crismond, 2001; Fortus, Dershimer, Krajcik, Marx, & Mamlok-Naaman, 2004; Kolodner, 2006; Sadler et al., 2000; Walkington et al., this volume), only Roth (1996) and Penner and colleagues (1997, 1998) have published studies addressing in detail the science-through-design learning of children age 10 and younger. Other scholars have looked at young children’s designing and building abilities and their knowledge of technological design (Baynes, 1994; Benenson, 2001; Bers, 2008; Cunningham, Lachapelle, & Lindgren-Streicher, 2005; Papert, 1980; Resnick, Berg, & Eisenberg, 2000), but in their published studies they have not addressed children’s participation in science through such design activities. Nevertheless, there remains a great deal of interest in incorporating engineering design into elementary school science (Brophy, Klein, Portsmore, & Rogers, 2008; Cunningham, 2009; Lewis, 2006; National Research Council, 2012).

In planning for our research, we drew heavily upon two classic approaches to design–based science instruction at the elementary school level and one at the middle school level: design–based modeling by Penner and colleagues (1998), engineering for children by Roth (1996), and Learning by Design by Kolodner and colleagues (2003). All three of these approaches understand design as an activity whose goal is the construction of a physical product, and this is of primary importance to our research group. In all of the approaches, students are initially tasked with creating a functioning device or system. The instructor typically establishes the purpose that the device or system should serve. The resulting construction is then considered an essential mediator of students’ learning. For Penner and colleagues the designed constructions enable model-based reasoning, deeper investigation of science concepts, and exploration of mathematical relationships. Roth sees each design construction as a tool to think with, a representation of cognitive processes, and a backdrop for class discussion and sense-making. Finally, in Kolodner’s work, the challenge of creating a functioning product provides motivation and opportunities for scientific reasoning and learning.

Across these three approaches, there are several commonalities regarding how classroom instructional practice is structured. All students work in groups, and interaction among students and improvement of communication skills are key goals of the teacher. As they work on solving the design problem, students are always expected to engage in written or pictorial record keeping. At some point, students are given the option to revise their designs. In addition to their individual record keeping and reflection, students reflect on their designing through participation in whole-class discussions. Importantly, throughout design–based science units, teachers provide guidance on how students can incorporate science ideas and careful reasoning into their design solutions. Researchers believe that this scaffolding is essential for preventing students from merely tinkering. We have incorporated all of these principles into the design of the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum units.

The curriculum

Instructional format. Before beginning any one of the Science through LEGO Engineering units, teachers enact two introductory lessons to introduce students to engineering and to the LEGO materials. After students discuss their initial ideas about what engineering is, the teacher shares examples of engineered products, a definition of engineering, and a five-part model of the engineering design process. Next, students are invited to classify items as “probably engineered” (e.g., a light bulb) or “probably not engineered” (e.g., a tree); finally, they are given time to explore basic LEGO construction techniques. After these experiences, teachers launch into one of the science curriculum units.

Each science unit includes 9 to 11 lessons designed to require one hour of instructional time, and each unit follows a similar instructional pattern. This pattern roughly approximates one cycle through an engineering design process. The find a problem activity occurs first: the first lesson in each unit focuses on specifying the grand engineering design challenge (see Figure 7.1) and the big science question for the unit. Students write about and discuss what they already know that will help them complete the challenge and answer the question, and they identify what they still need to learn. The research possible solutions aspect of engineering design comes next: in the next six to eight lessons of each unit, students carry out brief design challenges and science investigations to learn the knowledge and skills that will enable success on the grand design challenge. Most of these brief challenges and investigations involve the construction and testing of physical artifacts. Along the way, teachers guide students in reflecting on how their findings will inform the task of choosing the best solution. Finally, the build a prototype and test the prototype activities take place: in the last two to three lessons of each unit, students build, test, and improve their solution to the grand design challenge, and then present to their classmates an explanation of how it works.

Just as each overall unit follows the same pattern, each individual lesson is designed to follow a similar flow of events. The teacher’s guide for each unit recommends that the teacher begin each lesson by presenting the scientific question to be investigated that day. Next, students work independently for five minutes to respond to a related brainstorming prompt—called an exploration question. Students share their initial ideas and then, for the majority of the lesson, they work in dyads to complete the challenge and investigation of the day. Students find instructions for building and prompts for observing in their Engineer’s Journal, a workbook that is provided with the unit materials. The teacher’s guide suggests that the teacher conclude each lesson by facilitating a discussion of the summary questions in the students’ journals.

Instructional materials. Teachers and students are provided with the same general set of tools for each unit. These include (a) a teacher’s guide, (b) a student workbook that we call an Engineer’s Journal, (c) a written science content assessment, (d) an assortment of common craft materials, and (e) a kit of LEGO construction elements and electronic sensors for each student pair.

The teacher’s guide is intended both to specify lesson enactment and to support growth in the teacher’s science and pedagogical content knowledge. For each lesson, the guide includes eight sections: learning objectives, background information about the science content, typical preconceptions held by students, key vocabulary terms, materials to be gathered, preparation steps to be taken before the lesson, procedure for instruction, and tips for assisting students with building and testing.

The student Engineer’s Journal is a paper-and-pencil tool that guides the students through the unit’s engineering design process. For each of the 9 to 11 lessons in a unit, the journals provide introductory open-response questions, building and observation instructions, data recording prompts, and reflection questions. The prompts and questions ask for writing, drawing, and numerical inscriptions, and each is an opportunity for students to record their emerging content knowledge and practice skills related to the unit’s science domain.

The rationale for using a combination of LEGO tools and craft materials, instead of craft materials only, is that the interlocking building elements in the LEGO toolset have a low “cost” of prototyping and re-design (Bers, 2008). Because the LEGO elements do not require any assembly tools such as glue, tape, staples, or scissors, students can quickly create a first prototype. Also unlike glue, tape, or staples, the fastening mechanisms for LEGO pieces are sturdy but always temporary, so students can quickly reverse an action and move pieces around to change a design. Another reason for selecting the LEGO toolset is that its building elements are compatible with microprocessors and electronic sensor probes, and this allows for the interweaving of design challenges and sophisticated data collection. Finally, the LEGO toolset is a one-time investment that lasts for many years without the need for re-supply, and it is perceived by students to be a novel and motivating tool for science learning (Cejka, Rogers, & Portsmore, 2006).

The sound unit. In the opening lesson of the Design a Musical Instrument: The Science of Sound unit, students learn that their engineering design challenge is to create a new musical instrument that can play at least three different notes and contribute to a classroom band. Over the next six lessons, students conduct a series of guided design–based investigations to explore how sounds are produced, transmitted, and varied across different sound producers. Using LEGO construction kit elements and additional craft materials, they build a miniature drum, pan pipe, rubber-band guitar, and maraca. They explore the structural design of these instruments, observe how they look and sound when played, and identify the characteristics of the sounds they make. As students build and investigate these instruments, they are asked to describe relationships between physical characteristics and sound characteristics. For example, when the size of an object changes, how does the pitch of its sound change? Throughout the unit, students are encouraged to consider how these relationships can inform their design of a new musical instrument. In the unit’s two concluding lessons, students design, construct, and demonstrate musical instruments of their own invention. They also demonstrate what they have learned about the unit’s big science question, how are sounds made?

The properties of materials unit. The Design a Model House: The Properties of Materials unit begins with students’ learning that their engineering design challenge is to create a miniature model house that is stable, soundproof, waterproof, and thermally insulated. Over the next six lessons, the students conduct a series of engineering tests to identify materials to meet these design requirements. They compare clay and LEGO construction elements for their house frames, and they test quilt batting, polyurethane foam, cardboard, and transparent acrylic as choices for the house wall and roof surfaces. They use the LEGO microprocessor and electronic sound and temperature sensors as probes for testing. As the students test materials and begin prototyping, they are asked to make scientific arguments about the best materials for each portion of the house. They are encouraged to consider the material and object properties of stability, strength, soundproofing, waterproofing, insulation, and reflectivity. In the unit’s two concluding lessons, the students complete the design and building of their miniature model houses. The big science question of this unit is, how can we describe and choose objects and materials?

The animals unit. The Design an Animal Model: Animal Studies curriculum unit is intended to help students explore the structural and behavioral adaptations of animals. In the first lesson of the unit, students discover that their grand design challenge is to design a believable animal to be featured in a fictional adventure movie set in a tropical rainforest. To complete the challenge, they must build a movable model of the animal’s structures as well as a robotic model of its behaviors. After the opening lesson, the first phase of the unit focuses on introducing students to the tools and practices that animal biologists use, including species classification, habitat research, and field study. Then, in the fifth through eighth lessons, students learn about and practice constructing two kinds of models of animals: mechanical models of animal structures (e.g., a jointed model of a frog’s leg or a crab’s claw) and computer-controlled models of animal behaviors. Students apply their observations of real animal structures to construct movable LEGO models. With substantial teacher support, students apply their observations of live animal behavior to write computer programs that control LEGO motors and sensors to enact stimulus-response rules. Finally, in the concluding phase of the Design an Animal Model unit, each pair of students works independently to propose and model a “newly discovered” species that would be well-adapted to survive in the tropical rainforest ecosystem. This challenge is designed to help students construct an answer to the unit’s big science question, why do animals look and act the way they do, and how can we study and explain their looks and actions?

The simple machines unit. At the start of the Design a People Mover: Simple Machines curriculum unit, students find out that their grand engineering challenge is to design and build a model of an airport “people mover” machine—a new device that can move people up and across surfaces safely and quickly. In the subsequent seven lessons, students investigate seven types of simple machines (lever, inclined plane, wedge, screw, wheel-and-axle, pulley, and gear) by building a LEGO version and then using it to accomplish some physical task. For example, they build a LEGO lever to lift a small load, a LEGO egg beater (with wheel-and-axle system) to mix a bowl of beans, and a miniature LEGO pulley to hoist a small weight. With each simple machine, they make several small adjustments to designs that allow them to explore the trade-off between reducing the input force and increasing the distance over which the force must be exerted. In the ninth lesson, students practice identifying simple machines within complex machines. Finally, in the culminating two lessons, students work independently on the open-ended task of planning, constructing, and testing their own complex machine (with at least three identifiable simple machines) that functions as a miniature people mover. The goal of this series of learning experiences is for students to be able to answer the unit’s big science question, how can we design simple machines to be most helpful for doing work?

EVIDENCE OF STUDENT LEARNING

Paper-and-pencil tests

One tool we have used to study the impact of the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum is a set of paper-and-pencil science content tests. (We want to emphasize that in this work, we have considered engineering as a context for learning, not as a key learning goal itself. However, in other work we are keenly interested in the learning of engineering itself). Working with a team of researchers including engineers, math and science teachers, an educational psychologist, and education researchers, we developed one science content test for each of the four domains of sound, material properties, simple machines, and animal structure and behavior. Each test includes a mixture of multiple-choice and open-response items, and each curriculum learning objective is assessed by one item.

In other reports (Connolly, Wendell, Wright, Jarvin, & Rogers, 2010; Wendell & Rogers, 2013), we describe our quantitative analyses comparing test performance of Science through LEGO Engineering students to that of students using their district’s status quo curricula. Stated very briefly, the basic finding from those analyses is that the pre-post increase in science content score was significantly greater for the engineering- design–based students than for the comparison students (F(1, 640) = 23.276, p < .001). The engineering design–based students began their science units with less science content knowledge than the comparison students, but at unit completion they had equivalent science content knowledge as measured by paper-and-pencil tests. See Connolly et al. (2010) and Wendell & Rogers (2013) for further documentation of these results.

Here we focus on individual student change from pre-instruction to post-instruction on specific open-response test items. Let us consider two open-ended items from the properties of materials test, taken by third-grade students in engineering design–based science classrooms before and after the Design a Model House unit.

The first open-response item on the properties of materials test is intended to assess students’ competence at describing materials by their physical properties. We call this item the coat item. It states, “It is cold so you decide to wear your coat outside. Use a material property to explain why you would wear a coat instead of a T-shirt” (emphasis in the original). Responses are scored two points if they are based on a physical property of a coat, such as insulation, thickness, weight, layering, or waterproofing. Responses earn one point if they reasonably argue for wearing a coat but do not refer to a physical property. If a response is irrelevant (e.g., “I will use a thermometer.”) or if it merely reiterates the item prompt (i.e., “I would wear a coat because it is cold.”), it receives zero points.

Here we use the work of two third-grade students, Ryan and Karla, to illustrate the kind of positive change that occurred on this item for students experiencing the Design a Model House unit. Ryan and Karla gave pre-instruction responses that were typical of the majority of students. Neither used a physical property to reason about the effectiveness of a coat for protection from the cold. Essentially reiterating the item prompt, Karla earned zero points for her response, “If you wear a coat you won’t get freezing cold.” Ryan earned one point by arguing that he would wear a coat “because it’s cold and you might get sick.” By postinstruction, however, both produced responses that earned two points. Karla focused on the property of thickness: “I would wear a coat instead of a T-shirt because the coat is thicker. Then you won’t get a cold.” Ryan referred to the property of insulation, “You would wear a coat because a t-shirt doesn’t keep the warm inside you.” After participating in the Design a Model House unit, both Ryan and Karla made use of physical properties to argue for the superiority of a coat over a t-shirt in cold weather.

Another open-response item on the properties of materials test is designed to assess whether students can identify the materials from which objects are made. We refer to this item as the dream house item. It asks, “If you could use only one material to build your dream house, what would you pick? Why would this be useful for your house?” (emphasis in the original). In scoring this item, we give two points if a response mentions a building material and provides an explanation that is accurate for the chosen material, even if the chosen material is whimsical, like glass or gold. Responses receive one point if they mention a building material but provide an explanation that is based on feelings (e.g., “Wood because I think it is good.”). Responses receive zero points if they discuss shapes, structures, or tools rather than building materials (e.g., “Squares, because it makes sense to build a house out of squares.”)

The work of two different students, Julia and Theo, exemplifies the improvement made on this item by students participating in the engineering design–based curriculum. Before beginning the unit, neither Julia nor Theo indicated that they understood the phrase “material to build” to mean a raw ingredient for creating a structure. Both students gave responses that were scored zero points. Julia wrote about a possession that would go inside the house; she would select a “t.v.,” she wrote, “for when I get bored.” Theo focused on a tool rather than a substance; he wrote that he “would use a scroodriver,” and he explained, “It would be useful for my house because it would be able to do stuff.” By contrast, in his post-instruction response, Theo revealed that he understood what it meant to choose a building material and justify that choice according to the material’s properties. He chose “brick” for his house and explained, “It would be useful for my house because it would never break down.” Similarly, Julia chose “glass” to build her dream house on her post-test, and she accurately reasoned, “because it is waterproof.” The post-instruction responses of both Theo and Julia demonstrated a new understanding of material selection.

Clinical interviews

Clinical interviews are another tool we have used to investigate student learning. Wendell and Lee (2010) describe how the clinical interview approach was used to examine students’ materials science practices before and after the Design a Model House unit. Here, we describe an interview study related to the Design an Animal Model unit.

On the paper-and-pencil test for the Design an Animal Model unit, one of the openresponse items focuses on the task of modeling an animal structure. The item asks students to select from four common craft materials (paperclips, shoelaces, craft sticks, or yarn) the one best suited for modeling a functional spider leg and then to explain their choice. Inspired by the elbow modeling task described by Penner, Giles, Lehrer, and Schauble (1997), this spider leg item was used as the basis for a clinical interview study of fourth-grade students before and after their participation in the Design an Animal Model unit. The goal of the study was to evaluate the students’ modeling practices and metamodeling knowledge (Lehrer & Schauble, 2006; Schwarz & White, 2005).

In the study, each student first produced a written response to the spider leg item. Then, in an interview, he or she was given the same choice of four craft materials, was asked to construct a functional spider leg model, and was prompted to critique the model. The students then participated in the Design an Animal Model curriculum unit. After completing the unit, the students again responded in writing to the spider leg item. Finally, in a post-interview, each student expounded on his or her written response, constructed another spider leg model from any or all of the four craft materials, and critiqued the new model.

One student, Michael, showed particularly intriguing progress from before to after instruction. On the written pre-test, Michael chose paperclips as his modeling material. He wrote, “I would attach the paperclips together.” In the subsequent pre-interview, Michael was asked to critique this choice of paperclips. At this point he decided to switch to shoelaces. He reasoned that “when you pick [the model] up, it would move like a spider,” as he made a wiggling motion of his fingers over the table. This explanation demonstrates a limited conceptual understanding of the structure of spider legs since it represents them as almost cartoon-like. Michael’s critiques of his artifact reinforced this belief. He said he wished he had cut the shoelace-legs longer because, “if they were longer, but I made them short, they would hang down (shaking model back and forth) and when you shook it, it would start moving.”

In the post-interview, which took place after the curriculum unit, Michael once again initially chose paperclips for the spider legs. He gave the explanation, “because it would bend, you could move them when they’re in the little ball.” This explanation shows an increased consideration for the realism necessary in modeling animal motion. In the post interview Michael also noted the importance of the paperclips in providing stability for the spider’s legs. Prior to constructing his model, when asked if he would like to make a different material choice, he proposed an alternate way to construct the spider legs using both paperclips and craft sticks. This plan was structurally and conceptually very advanced, but Michael had trouble using the actual materials to construct his articulated “knee joints,” as he called them. After many iterations during the interview, he settled for a much simpler but arguably less functional design. As he worked, he considered out loud the trade-offs between the materials’ capabilities and his goals for a sturdy and bendable spider. By the end of the post-interview, his model was still not movable, but his narration of his problem-solving process allowed sufficient insight into his matured beliefs about modeling and the structure of spiders.

Lehrer and Schauble (2006) suggest that a curriculum with an emphasis on modeling requires adjustments in students’ epistemic goals, since they become inventors of models and not just consumers and appliers of models found in textbooks. The learning goals of the Design an Animal Model curriculum focused not only on traditional content, such as categorizing animals by family and describing environments necessary to sustain life, but also on characterizing animal structures and understanding how they allow the animal to survive in varied biomes. This is reflected by the transition from cartoon-like, wiggling legs to complex ideas about “knee joints” in Michael’s models. The emphasis on engineering design during the curriculum unit may also have helped students select appropriate materials for functional modeling of these animal structures. Finally, classroom activities and the Engineer’s Journals were intended to support students in critiquing their own and their classmates’ models. This may have helped them make better material and construction choices in the post-interviews, as evident in Michael’s repeated revisions of his post-interview design when it did not meet his criteria. Revision of models is an important aspect of metamodeling knowledge (Schwarz & White, 2005), but unless students look for and identify problems with their model, they will see no reason to revise the model. Like Michael, the students in this clinical interview study generally showed more and higher-quality justifications for their material choice after the Design an Animal Model unit than before.

Whole-class discussions

We also see evidence of student learning in the whole-class discourse that occurs over the course of a Science through LEGO Engineering unit. At the beginning of each lesson, teachers facilitate a large-group discussion to elicit student ideas about the phenomena being considered in that lesson. We find that the students’ expression of their scientific ideas becomes more complex as the unit progresses.

We find an example of this in one class’s discussion of musical pitch during the Design a Musical Instrument unit. See Wendell (2011) for extended documentation and analysis of whole-class discussion during this unit. Before students began to build and test miniature rubber-band guitars, their teacher had them share their ideas about how different pitches are made. This large-group conversation was the first one focused on the topic of pitch. Already, the students’ oral responses exhibited reasonable thinking about the phenomenon. They expressed the ideas that higher pitch is produced by harder pushing, thinner strings, and tighter strings.

Ms. Boyle: So, what do people think? I’d like to hear from a couple people. What do you think? Jason?

Jason: That the strings make them.

Ms. Boyle: The strings help make the different notes.

Jason: On a guitar.

Ms. Boyle: Okay. Anybody want to add to that? Maybe they also used the example of a guitar? Janice?

Janice: I think the harder you push on the string, the higher the note gets.

Ms. Boyle: You think maybe the way you push on the string or pull on the string can change the sound of the note? Okay. Harrison?

Harrison: I kind of agree with her, but I think that there’s fatter strings and there’s thinner strings, and when you press on the fatter string, it makes a lower noise.

Ms. Boyle: So you’re saying that the bigger, the thicker the string is, the lower the sound you’ll get, the lower the pitch. So that mean the opposite, then, that a skinny string would give us a high pitch sound?

Students: [Several students make silent gestures that mean “me, too.”]

Ms. Boyle: I see some people giving me the nonverbal signal for “me, too,” so I’m glad to see that other people think that way as well. Anybody else have something else they want to add, maybe a different instrument that they used to help them understand this?

David: I didn’t use a different instrument, but I think it matters how tight they are. If they’re tighter, the pitch is higher, and if they’re not as tight, but if they’re still pretty tight, then um, then the sound’s lower.

Coming from third graders, this set of ideas was already quite sophisticated. However, after this discussion, the students proceeded to do some musical instrument engineering: they built and manipulated miniature guitars. A week later, their teacher facilitated another discussion on how pitch is determined. Drawing upon their experiences with their miniature guitars, the students worked together to expand on the idea that more tension creates higher pitch. This time, their oral expressions featured more depth of explanation. In the excerpt below, notice that David expands on his initial idea by explaining why tension affects pitch; he thinks vibration speed has something to do with it. Furthermore, both he and Eric make reference to discoveries they had made “last week.” They are using observations made during engineering testing as evidence for their scientific claims.

Ms. Boyle: So I’d like to hear from a couple people, what do you think? What’s gonna give you a higher pitched sound? And I’d love to also hear why you think that. David, I remember hearing your answer. I’d like you to share it, what do you think?

David: Um, the tight rubber band because um, last week, we figured out that the faster it vibrates, the tighter it is, and I think if it’s, I mean, the higher pitch it is, and um, I think if it’s tighter, it vibrates faster.

Ms. Boyle: And the faster you vibrate, then the higher pitched the sound is going to be, right? Okay. Sasha?

Sasha: I agree with David, but um, I’m thinking, I was telling Kristen that like if you pull more to the thingy, like the more sound it makes.

Ms. Boyle: … Anybody else have something they’d like to add on to that? Or maybe you completely disagree, and if you do we’d like to hear what you’re thinking, okay? Eric?

Eric: I agree with David, too, and when you like tighten it really high, like when we pushed it down last week… . And that’s how we got our higher pitch, so if we wind it up more, even still, we’ll get a really high pitch.

Student journals

The Engineer’s Journals used during Science through LEGO Engineering units are key learning tools for students, but they also serve as important assessment tools for teachers and researchers. One case that illustrates the journals’ usefulness for investigating learning comes from the Design a People Mover: Simple Machines curriculum. In this unit, the grand design challenge is to create a complex machine that can move a LEGO figurine (a model for a person) and a weighted LEGO brick (a model for the person’s luggage) up 6 inches and over 18 inches. In the journal for this unit, students are given repeated opportunities to revise their plans for their miniature people-mover machine. On the last page for each lesson, the journal provides space for students to draw and write about the current state of their design ideas. Figure 7.2 shows the progression of people-mover plans created by Kyle, a fourth grader. Out of the 11 lessons of the unit, he produced people mover plans after Lessons 1, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

On Day 1 of the unit, Kyle drew only a vague outline of the path his LEGO figurine and brick would take, and he wrote only to reiterate the purpose of the machine: “It should move both human and the logige (luggage).” On Day 4, after an introduction to simple machines and two investigations of levers, he drew a more elaborate pathway and wrote one detail about a feature his machine: it would include “the ‘pull down’ thing.” But he did not describe how this “pull down” feature would operate or whether it would incorporate any simple machines. By Day 6, this changed. His drawing and writing began to include specific simple machines that he had been investigating in the curricular unit. The written explanation for his Day 6 plan suggests that a pulley will do all the work for his people mover machine. However, from Kyle’s drawing it is difficult to draw any conclusions about his ideas about a pulley’s appearance or function. The portion of his drawing labeled “pulley” is detached from the rest of this drawing, and it is ambiguously shaped like a square with a circle next to it. It could be that at this point in the curriculum unit, Kyle guessed that the simple machine called a pulley would probably be useful for the task of moving something up and over, but he did not yet know what one looks like or how it works. Coincidentally for Kyle, however, Lesson 7 guided him through building and investigating actual pulley systems. Kyle’s Day 7 drawing shows a much more recognizable representation of a pulley, with a pulley wheel, a rope draped over it, a human figure pulling one end of the rope, and a load attached to the other end of the rope. This load, according to Kyle’s caption, is a lever. It appears that Kyle was planning to have a pulley transfer motion to a lever. His plan seems to stop there, though, since the square shape representing the lever is detached from the rest of the people mover pathway, and the written caption provides no information about the function of the lever.

Showing progress in his thinking, Kyle resolved this problem in the sketches he created on Days 8 and 9. These were the last two lessons before he finally built and tested his people mover. In his Day 8 and 9 sketches, Kyle drew an uninterrupted chain of motion transfer from the machine operator (a stick figure) to the machine exit (a rectangular area at the opposite end of the people mover pathway). The operator tugs on a pulley rope; the other end of the rope lifts a lever arm; the lever sets a gear train in motion; the moving gears start the person and luggage moving along an inclined plane. To be sure, although this chain of motion transfer is uninterrupted, it is not fully specified. It is unclear where the person and luggage begin their journey through the people mover machine, and it is left to our imagination to determine how the gear train leads to motion down (or up) the inclined plane. Moreover, Kyle’s representation of the lever remains a generic “black box.” Nevertheless, from Day 1 to Day 9, Kyle’s engineering design plans progressed a great deal. He substantially increased the level of detail expressed in his drawing and writing, he accurately represented the basic appearance and function of at least three simple machines, and he reasonably incorporated at least four simple machines into his design. His Day 9 plan might not fully specify how motion is transferred from one element to the next, but we can envision ways in which that motion transfer could reasonably be made to occur. Kyle’s Day 1 plan does not suggest how to proceed with building a machine. It stands in great contrast to his Day 9 plan, which incomplete as it is, could certainly serve as the basic blueprint for a functioning device.

TEACHER PERCEPTIONS

Throughout the entire course of our research program, we frequently solicited and incorporated informal feedback from our teacher partners. In addition, at the end of the fourth year of our program, we conducted a formal focus group study with six teachers to gather their perceptions of the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum. They were asked to share their opinions about several different topics relating to the curriculum, including comparisons to their previous science units, support needed for enacting the units, perceptions of student learning, and assessment of student learning. Through open coding and constant comparative analysis of the focus group transcript, we uncovered two major elements considered by the teachers to be important to their students’ science learning: (1) the coherent storyline offered by the overarching engineering design challenge, and (2) the Engineer’s Journal as a scaffold for students’ written expression.

The teachers perceived the Science through LEGO Engineering curriculum to be well structured and coherent. As suggested in the following quotation from the focus group, they viewed its coherence as contributing positively to their students’ understanding of the science ideas.

Teacher: I think that the coherency of the curriculum makes a huge difference compared to the regular kit, like the [popular elementary science curriculum] animal kit compared to the LEGO kit, and they come out learning [with the LEGO kit] so much more about animals and how they function in habitats than they did before.

Some of this structure came from the use of student Engineer’s Journals, which provided opportunities for students to share their prior knowledge about a topic at the beginning of a lesson, record data from experiments during the lesson, reflect upon new ideas at the end of a lesson, and plan for their execution of the design challenge. The teachers reported that a major affordance of the journals was that they allowed students to represent their ideas in many different modalities. The journal prompts almost always encouraged both written and pictorial expression, especially diagrams with labels, so that students were producing scientific ideas in words and pictures. In addition, many teachers found the prompts in the journal to be good starting points for students’ oral expression during class discussions.

Teacher: I think my class learned how to give evidence for their thoughts with the journals because we would have a discussion after [a science lesson]. We’d sit in a circle, and we’d talk about the lesson, and the kids would bring their notebooks with them, and I’d ask them a question about what we just did. And when they’d raise their hand and give their answer I’d say, “How do you know that?” And at the beginning they would just look at me like, “Because we just did the lesson, you stupid!” But then I’d say, “Look at your notes, what does it say?” so they had to go back and prove what they know, with those journals. And that was really great. I think it sort of carried over into my reading lessons as well because you know the comprehension questions, I’d say, “Well, how do you know that’s the answer? Prove it.” So it carries over across the subjects.

In one classroom, a teacher decided to use the Science through LEGO Engineering curricular format as a model for her other science units. For her lessons on rocks and minerals, she created student journals and incorporated tables and prompts that encouraged students to act as amateur geologists.

Teacher 1: We’ve created a little rocks and minerals journal for the rocks and minerals that we do in third grade, and created a challenge the way that they did with this, where you kind of become an amateur geologist. At the end they [the new journals] ask the kids to identify some mystery minerals. I found that, I found it a little bit easier when I create some graphs and some charts to go along with it, which I thought they [her previous rocks and minerals lessons] were lacking.

Teacher 2: [The journals are] so useful for teaching kids scientific methods of recording and labeling and drawing to back up what they write.

Finally, the teachers appeared to believe that students were also engaging in the practices of scientific inquiry through the Science through LEGO Engineering units, largely with scaffolding from the Engineer’s Journals.

Teacher 3: Well, I think that when I did properties and materials [Design a Model House] with the third graders, I think they learned not only properties and materials, but they learned a lot about experimenting. How to conduct experiments, how to have … and you know a lot of them kept saying, “Well what should the right answer be?” and I said, “Well you’ve got to find out what the right answer is, there is no right answer, just do the experiment and whatever comes out, comes out.”

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

These teacher perceptions lead us to some closing comments about the value of engineering design–based (EDB) science instruction. It was beyond the resources of the Science through LEGO Engineering research program to provide the level of proof of a controlled experimental study. Nevertheless, our various classroom-based studies have demonstrated the positive student outcomes that can occur in elementary classrooms using EDB science curriculum. For the students who have experienced our curriculum units, the power of the EDB approach has stemmed from its ability to create rich opportunities for three kinds of activities: deep reasoning about how things work (i.e., mechanism), sustained experimentation with physical materials and their effect on observable phenomena (i.e., scientific inquiry), and authentic planning and construction of physical artifacts to meet specific requirements (i.e., design). For example, when they participate in the Design a Musical Instrument curriculum unit, elementary students think about the mechanisms of sound, engage in scientific inquiry about existing sound-producing devices, and succeed in engineering their own functioning musical instruments. They also contribute to lively whole-class discussions, produce sophisticated drawing and text to express their scientific ideas, and collaborate with other students in bringing design ideas to fruition. The EDB approach is a powerful mode of elementary school science instruction.

Of course, there are challenges to providing science instruction through engineering design. For one, the scientific concepts that seem evident to the curriculum developer and teacher may not emerge for the students. One reason for this discrepancy is that if students are given enough time and materials, they can complete many engineering design problems through trial-and-error methods only. In addition, some design problems are solvable based only on prior knowledge of already existing artifacts. For example, students might design successful miniature guitars based on the appearance of real guitars they have seen in photographs. To deal with these obstacles to science learning, students’ trial-and-error discoveries and intuitive experiences with design should be articulated and formalized. This is why our curriculum units emphasize reflection on why design constructions succeed or fail.

Another challenge of EDB science instruction is that of facilitating lessons where there are always multiple “right answers” and multiple paths to arrive at each answer. After a class session in which each student has created a different design construction, achieving progress toward a scientific explanation requires the teacher to determine quickly how to apply her own science knowledge to the unpredictable creations of students and then to transition students from physically manipulating materials to cognitively operating on ideas. For instance, when helping students articulate how their musical instrument constructions create sounds with different characteristics, teachers need their own firm understanding of how physical variables affect pitch and volume. To address this challenge of EDB science instruction, our curriculum materials provide background support for teachers to develop their science understanding as well as strategies for how to apply it to the particular engineering activities their students will be completing.

Finally, EDB science instruction can be difficult simply because of the time constraints of the elementary school schedule. Many EDB units require a substantial time commitment since instruction that weaves back and forth between design endeavors and inquiry explorations can take longer than instruction focused on only one kind of activity. For example, the teachers who have enacted the Design a Musical Instrument curriculum find that sometimes they have to allow students to make final touches to their musical instruments during free-choice period or to complete their Engineer’s Journal work during language arts block. Another way to deal with this challenge would be to consider narrowing the breadth of the elementary science curriculum in order to increase its depth.

Acknowledging the special challenges described above, we argue that the benefits of EDB science curricula for student outcomes make worthwhile the extra considerations associated with implementing EDB curricula. As demonstrated by the students and teachers in our classroom-based studies, the integration of design and inquiry can provide a deep, rich set of experiences for children to draw upon when conducting scientific reasoning and constructing scientific knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant #0633952 to the Tufts University Center for Engineering Education and Outreach. The opinions, findings, and recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. We wish to thank our colleagues Kathleen Connolly, Ismail Marulcu, and Michael Barnett for all of their contributions to curriculum and assessment development, and we also wish to thank the students and teachers whose enthusiastic participation have made this work possible.

REFERENCES

Baynes, K. (1994). Designerly play. Loughborough, England: Loughborough University of Technology.

Bell, P., & Winn, W. (2000). Distributed cognitions, by nature and by design. In D. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Benenson, G. (2001). The unrealized potential of everyday technology as a context for learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(7), 730–745. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.1029

Bers, M. U. (2008). Blocks to robots: Learning with technology in the early childhood classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Brizuela, B. M., & Earnest, D. (2008). Multiple notational systems and algebraic understandings: The case of the “Best Deal” problem. In J. Kaput, D. Carraher, & M. Blanton (Eds.), Algebra in the early grades (pp. 273–301). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brophy, S., Klein, S., Portsmore, M., & Rogers, C. B. (2008). Advancing engineering education in P-12 classrooms. Journal of Engineering Education, 97(2), 1–19.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032

Cejka, E., C. Rogers, and M. Portsmore. (2006). Kindergarten robotics: Using robotics to motivate math, science, and engineering literacy in elementary school. International Journal of Engineering Education, 22(4): 711–722.

Connolly, K. G., Wendell, K. B., Wright, C. G., Jarvin, L., & Rogers, C. (2010). Comparing children’s simple machines learning in LEGO engineering-design-based and non-LEGO engineering-design-based science environments. Annual International Conference of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching (NARST). Philadelphia, PA.

Crismond, D. (2001). Learning and using science ideas when doing investigate-and-redesign tasks: A study of naive, novice, and expert designers doing constrained and scaffolded design work. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(7), 791–820. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.1032

Cunningham, C. M. (2009). Engineering is elementary. The Bridge (Fall), 11–17.

Cunningham, C. M., Lachapelle, C., & Lindgren-Streicher, A. (2005). Assessing elementary school students’ conceptions of engineering and technology. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition. Portland, OR. June 12-15.

Fortus, D., Dershimer, R. C., Krajcik, J. S., Marx, R. W., & Mamlok-Naaman, R. (2004). design–based science and student learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(10), 1081–1110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.20040

Grigorenko, E. L., Jarvin, L., & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). School-based tests of the triarchic theory of intelligence: Three settings, three samples, three syllabi. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 167–208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1087

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kolodner, J. L. (2006). Case-based reasoning. In K. L. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 225–242). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kolodner, J. L., Camp, P. J., Crismond, D., Fasse, B., Gray, J., Holbrook, J., … (2003). Problem-based learning meets case-based reasoning in the middle-school science classroom: Putting Learning by Design (TM) into practice. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 12(4), 495–547.

Krajcik, J. S., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (2006). Project-based learning. In K. L. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 317–333). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2006). Cultivating model-based reasoning in science education. In K. R. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 371–387). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, T. (2006). Design and inquiry: Bases for an accommodation between science and technology education in the curriculum? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 43(3): 255–281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.20111

National Research Council Board on Science Education. (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Board on Science Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York: Basic Books.

Penner, D. E., Giles, N. D., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (1997). Building functional models: Designing an elbow. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(2), 125–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199702)34:2<125::AID-TEA3>3.0.CO;2-V

Penner, D. E., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (1998). From physical models to biomechanics: A design–based modeling approach. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7(3/4), 429–449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10508406.1998.9672060

Resnick, M., Berg, R., & Eisenberg, M. (2000). Beyond black boxes: Bringing transparency and aesthetics back to scientific investigation. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 9(1), 7–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0901_3

Roth, W.-M. (1996). Art and artifact of children’s designing: A situated cognition perspective. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 5(2), 129–166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0502_2

Roth, W.-M. (2001). Learning science through technological design. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(7), 768–790. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.1031

Sadler, P. M., Coyle, H. P., & Schwartz, M. (2000). Engineering competitions in the middle school classroom: Key elements in developing effective design challenges. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 9(3), 299–327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327809JLS0903_3

Schwarz, C. V., & White, B. Y. (2005). Metamodeling knowledge: Developing students’ understanding of scientific modeling. Cognition and Instruction, 23(2), 165–205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci2302_1

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). The development of scientific concepts in childhood. In L. S. Vygotsky (Ed.), Thought and language (pp. 82–118). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11193-006.

Wendell, K. B. (2011). Science through engineering in elementary school: Comparing three enactments of an engineering-design-based curriculum on the science of sound. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/45/3445103.html.

Wendell, K. B., & Lee, H.-S. (2010). Elementary students’ learning of materials science practices through instruction based on engineering design tasks. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 19(6), 580–601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10956-010-9225-8

Wendell, K. B., & Rogers, C. (2013). Engineering-design-based science, science content performance, and science attitudes in elementary school. Journal of Engineering Education, 102(4), 513–540.