Chapter 8

Entertainments: Epic and Domestic

In This Chapter

The games people watched and where they watched them

The games people watched and where they watched them

The brutal life of a Roman gladiator

The brutal life of a Roman gladiator

Attacking animals, mock battles, and spectacular shows

Attacking animals, mock battles, and spectacular shows

Grand Prix racing – Roman style

Grand Prix racing – Roman style

What the Romans watched at the theatre

What the Romans watched at the theatre

How Romans enjoyed themselves at home

How Romans enjoyed themselves at home

The two most famous Roman movies ever, Spartacus (1960) and Gladiator (2000), have one thing in common: the brutal world of the Roman gladiator and his short, dangerous life. They give the impression that every Roman spent his every waking hour down at the amphitheatre watching men fight to the death. Now for some Romans that might have been true, so this chapter starts with arenas and gladiators, a distinctly Italian form of entertainment with ancient origins that found a ready audience in parts of the Roman Empire.

There were also the incredible chariot races. Operated at lunatic speeds by superstar charioteers, they were the ultimate thrill for Roman boy racers. For people with politer tastes, and there were plenty of them, there were the theatres for plays and pantomimes, and little odeons for readings and poetry. And there were also the pleasures of stopping in and having dinner parties.

Introducing the Games

For most people in the Roman Empire, life was nasty, brutal, and short. In a world where war was common, where anyone could carry a lethal weapon, where appalling accidents at work happened all the time, and where people born with any kind of handicap were extremely unlikely to get medical help, physical violence and cruelty were taken for granted.

That’s why most people who took part in public entertainments were slaves. If free people didn’t matter much, then slaves didn’t matter at all. Slaves were just a resource, and as far as the Roman authorities were concerned, one of the best ways of using them was in entertaining the mob and keeping it off the streets.

.jpg)

Bonding the population

Upper-class Romans originally looked down on public entertainment as a vice because games were thought undignified and nothing to do with ‘proper Roman virtues’ of restraint and self-discipline. So even when they put on an event in the early days, Roman aristocrats tried as hard as possible to make sure nobody enjoyed them. There weren’t any seats at gladiatorial fights, for example, so everyone had to stand. When the Romans got round to putting up venues for these events to take place in, they took them apart straightaway afterwards out of a sort of shame but also because they were terrified of getting a crowd of the lower classes all together in one place.

Nevertheless, the games proved a great cultural way to bond the population, because they helped reinforce the religious connection and kept the mob out of trouble. No wonder the terrible days of the Second Punic War (discussed in Chapter 12) were when public games became more and more important.

The mob had no hang-ups about the games, so during the late Republic, men like Sulla and Caesar soon realised how putting on free games for the mob at their own personal expense could increase their popularity ratings. Later emperors followed the trend, and so did local politicians all round the Empire. A sort of free-for-all occurred, in which anyone who could afford it put on games, trying to buy political advantage and popularity. Not surprisingly, Roman historians of the day blamed the loss of ‘proper Roman virtues’ on all this crowd-pleasing, though they never asked themselves what the crowds would be doing if they weren’t being kept busy in the arena or at the circus.

The gaming calendar

Roman public entertainments were an important part of the annual religious calendar. The Ludi Consualia (see the list in the next paragraph) were dedicated to Consus, another name for Neptune, god of the sea. His Greek equivalent, Poseidon, was also associated with horses. So you can see why chariot-racing might end up being associated with Neptune. Rather obscure but, as a later Roman writer called Tertullian discovered while researching the games for his book On the Spectacles, it was no clearer to the Romans.

By the time of the Empire, the annual religious calendar and its games were pretty well sorted out and getting on, for around half the year was allocated to religious holidays with games (ludi). These games included everything from chariot-racing to animal fights and gladiatorial bouts. Some, like the Ludi Cereales, went back to some remote part of Rome’s ancient mythical past, while others were connected with politics and war. These are the main ones, but there were others – almost any excuse would do:

The Megalian Games

(Ludi Megalenses): Celebrated 4–10 April with their origins in the introduction of the Great Mother (Magna Mater) of the gods, Cybele, in Rome in 204 BC.

The Megalian Games

(Ludi Megalenses): Celebrated 4–10 April with their origins in the introduction of the Great Mother (Magna Mater) of the gods, Cybele, in Rome in 204 BC.

The Cerealian Games

(Ludi Cereales): Celebrated 12– 19 April in honour of Ceres, the goddess of harvests and her children, Liber and Libera, deities of planting.

The Cerealian Games

(Ludi Cereales): Celebrated 12– 19 April in honour of Ceres, the goddess of harvests and her children, Liber and Libera, deities of planting.

The Floral Games

(Ludi Florales): Celebrated 28 April to 3 May in honour of Flora, a goddess of flowers and also associated with licentious behaviour.

The Floral Games

(Ludi Florales): Celebrated 28 April to 3 May in honour of Flora, a goddess of flowers and also associated with licentious behaviour.

The Apollinarian Games

(Ludi Apollinares): Celebrated 6–13 July and given for the first time in 212 BC to celebrate the defeat of Hannibal at Cannae. Dedicated to Apollo.

The Apollinarian Games

(Ludi Apollinares): Celebrated 6–13 July and given for the first time in 212 BC to celebrate the defeat of Hannibal at Cannae. Dedicated to Apollo.

The Consualian Games

(Ludi Consualia): Celebrated twice a year, on 21 August and again on 15 December.

The Consualian Games

(Ludi Consualia): Celebrated twice a year, on 21 August and again on 15 December.

The Roman Games

(Ludi Romani): Celebrated 5–19 September in honour of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the king of the gods, and the ultimate power over Roman destiny.

The Roman Games

(Ludi Romani): Celebrated 5–19 September in honour of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the king of the gods, and the ultimate power over Roman destiny.

The Plebeian Games

(Ludi Plebei): Celebrated 4–17 November. They were started during the Second Punic War (218–202 BC) to keep up morale amongst the public (the plebs).

The Plebeian Games

(Ludi Plebei): Celebrated 4–17 November. They were started during the Second Punic War (218–202 BC) to keep up morale amongst the public (the plebs).

It’s very unlikely whether any of the spectators screaming with excitement gave a moment’s thought to the religious origins of the games. So, let’s get on with the action!

The Playing Fields: Arenas and Stadiums

In the early days, almost any open area would do for putting on games. Right down to the days of Augustus, the Forum in Rome was used. Archaeologists have discovered that temporary wooden seats were erected around an area in the middle of the Forum where there were specially designed underground tunnels equipped with lifting machinery to raise weapons, scenery, and other gear for the action. When the games were over, the seats were removed and the underground chambers closed until the next time. The Colosseum (see the section ‘The Colosseum’, later in this chapter) later exploited this technology to the full, but made it permanent.

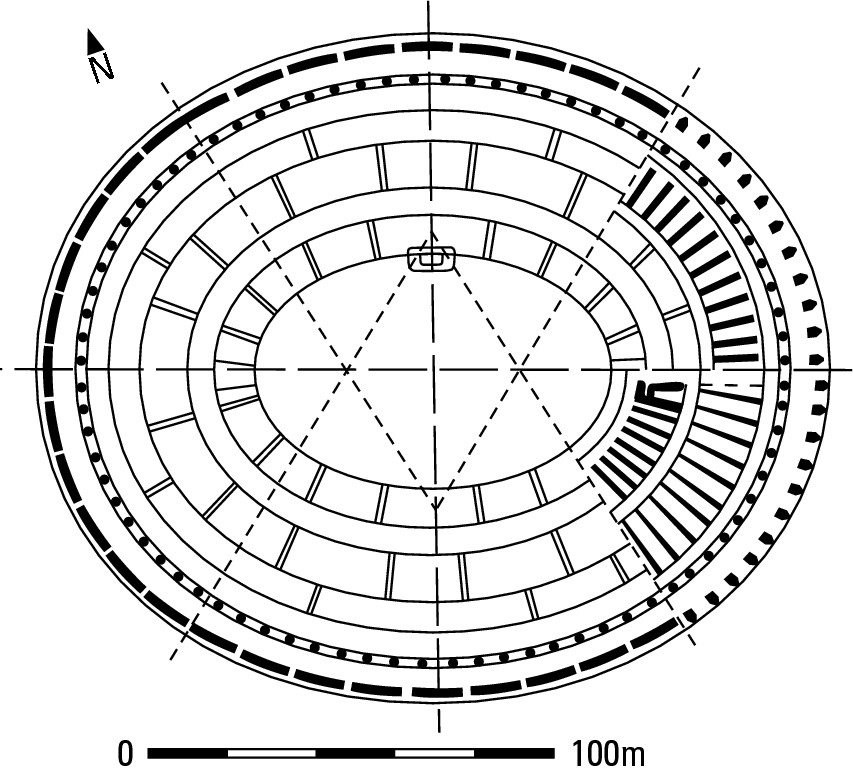

Rome didn’t get a stone amphitheatre until 29 BC when Statilius Taurus built one in Mars Field. Funnily enough, the oldest known permanent arena, or amphitheatre, isn’t in Rome but at Pompeii. It was built in 80 BC and was large enough to hold 20,000 people. Like all amphitheatres, Pompeii’s had an elliptical arena surrounded by rows and rows of seats raked at an angle so that all the spectators could get a view (see Figure 8-1). In case of any danger from the gladiators or wild beasts, a high wall separated the contestants from the public.

|

Figure 8-1: Pompeii’s ancient amphithe-atre, dating to 80 BC, and the oldest known. |

|

Photo by the author.

Arenas could be used for several things:

Gladiator bouts

Gladiator bouts

Animal hunts

Animal hunts

Re-enactments of great battles and naval events for the mob

Re-enactments of great battles and naval events for the mob

Displays of mock battles by army units for soldiers’ entertainment

Displays of mock battles by army units for soldiers’ entertainment

Religious festivals

Religious festivals

Building an arena

Arenas were usually built towards the edge of major cities or even outside the city walls. Soldiers also built them, generally just outside the walls of their forts. They also turn up sometimes at religious shrine sites in the countryside. They’re generally amongst the biggest buildings put up by the Romans, but they range from colossal pieces of masonry architecture like the massive example at El-Djem in Tunisia, to ones where wooden seats were fitted to banks of earth surrounding a dug-out arena, as in Silchester in Britain. Small towns either didn’t have them at all or just put up temporary wooden arenas which have left no trace.

Amphitheatres are mainly known in Italy, Gaul, parts of North Africa, Spain, and Britain, but scarcely ever appeared in the East where the Greek tradition of the theatre remained dominant. But there is the odd exception. The Romans added an amphitheatre to the great Greek city of Pergamon in Asia Minor, for instance. The most elaborate arenas had subterranean areas for storing animals, prisoners, and gladiators, and lifting gear to bring them up to ground level. They also had hydraulic equipment for flooding the arena for naval battles, and drainage systems – the water could also be used to flush out the blood and gore after the killing had finished.

Roman society was strictly hierarchical, and that was reflected in who got the best seats in the arena. The emperor, his family, and hangers-on had a kind of ‘royal box’. Senators took the front rows, behind them came the equestrians, and then citizens. Their women sat behind them, and next came the lower classes in the higher rows and standing-room-only.

The Colosseum

The most famous and impressive amphitheatre of all is the Colosseum in Rome, a very large part of which still stands and dominates the middle of the city (see Figure 8-2). It was started by the emperor Vespasian (AD 69–79) who used the site of Nero’s Golden Palace (see Chapter 16 for more on Nero). Since Nero (AD 54–68) had helped himself to large areas of Rome in order to build his extravagant residence, Vespasian knew that building a whopping entertainment centre on the same site was an excellent way to buy popular support.

The genius of the Colosseum was the design, and it was typical Roman: big, brash, and completely practical. Fully equipped with state-of-the-art underground chambers and hydraulics, it also had a vast sun roof that could be stretched over the crowd to keep the spectators in the shade. The underground operations took place in nine tunnel sections, with numerous work-rooms branching off them. One quarter of the arena was made up of moveable flooring which acted as ceilings for the tunnels. They were pivoted at one side and were lowered by ropes and pulleys into the tunnels where scenery was prepared. Then they were raised while fighters and animals were sent up top through trap doors and elevators. Just to get an idea of the kind of killing spectacle the Colosseum could handle, as well as getting all the punters in and out in double-quick-time, under Trajan (AD 98–117), games were held to celebrate his conquest of the Dacians and an almost unbelievable 10,000 gladiators fought.

|

Figure 8-2: The Colosseum, large enough to accommo-date 70,000 spectators. |

|

Stadiums

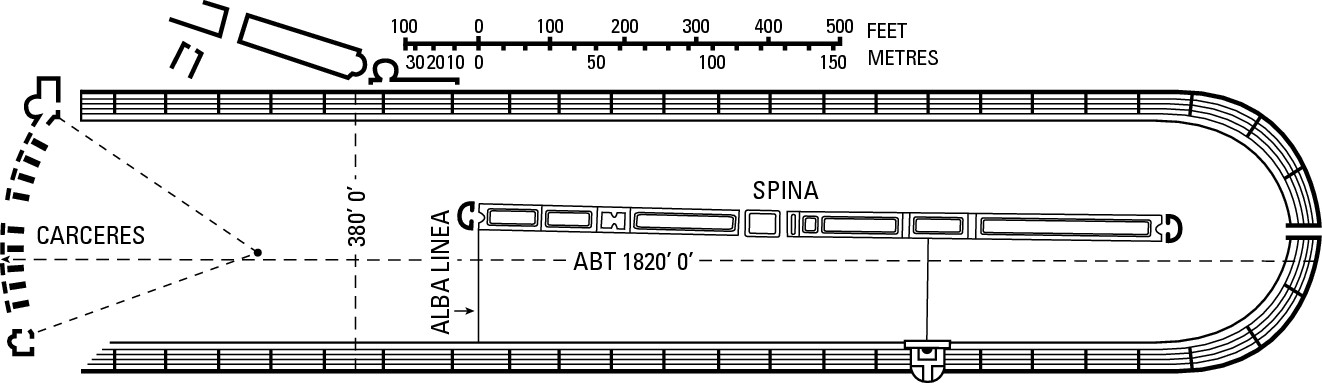

The stadium (or circus) was used for chariot-racing. A stadium had a long rectangular enclosure, curved at one end, with seats all round except at the straight end. Down the middle was the spine (spina), which the chariots hurtled around, lap after lap, trying to cut in front of each other.

Rome had eight chariot stadiums alone, and most other major cities either had a permanent stadium or an open field that could be set up as a temporary venue. Until very recently, far-off foggy Britain was thought to be an exception, but now one’s been found at Colchester, putting it on a par with great cities of the East like Aphrodisias in Asia Minor (Turkey), which has one of the best-preserved.

Rome’s greatest circus was the monumental Circus Maximus, (‘The Greatest Circus’). It’s one of, if not the, biggest buildings ever erected in world history for a spectator event. The first races were held here right back in the semi-mythical days of the kings of Rome. By the days of the emperors, it had been extended and enlarged. The Circus Maximus is still visible today in Rome, but most of the structures remain buried. One of the best-preserved is the Circus of Maxentius just outside Rome’s walls by the Appian Way; Figure 8-3 shows its plan.

Colossal Colosseum fun facts

It took 12 years to build the Colosseum out of thousands of 5-ton blocks of stone.

It took 12 years to build the Colosseum out of thousands of 5-ton blocks of stone.

Efficient use of arches and vaults meant only 9,198 cubic metres (325,000 cubic feet) of stone were used (the Empire State building used ten times as much).

Efficient use of arches and vaults meant only 9,198 cubic metres (325,000 cubic feet) of stone were used (the Empire State building used ten times as much).

The blocks were held together by 300 tons of metal clamps.

The blocks were held together by 300 tons of metal clamps.

The Colosseum was 186 metres (611 feet) long and 154 metres (507 feet) wide and could accommodate 70,000 spectators, meaning it would still be in the Top Twenty stadiums in Europe today, beating the new Emirates Stadium for Arsenal in London by 10,000!

The Colosseum was 186 metres (611 feet) long and 154 metres (507 feet) wide and could accommodate 70,000 spectators, meaning it would still be in the Top Twenty stadiums in Europe today, beating the new Emirates Stadium for Arsenal in London by 10,000!

There were 76 numbered entrances. Tickets were issued with specified entrances on them so the 70,000-strong crowd knew where to go and where to exit in an emergency.

There were 76 numbered entrances. Tickets were issued with specified entrances on them so the 70,000-strong crowd knew where to go and where to exit in an emergency.

Estimated exit time for all 70,000 spectators was three minutes!

Estimated exit time for all 70,000 spectators was three minutes!

The Colosseum wasn’t finished until the reign of Vespasian’s son Titus (AD 79–81) and was dedicated in AD 80.

The Colosseum wasn’t finished until the reign of Vespasian’s son Titus (AD 79–81) and was dedicated in AD 80.

It got its name because a colossal bronze statue of Nero stood close by, later adapted into a Sun-God. Pliny the Elder described the statue, called the Colossus, as 32 metres high and ‘breathtaking’. Because everyone knew where the statue was, it eventually became a kind of address tag for the new arena and the name stuck.

It got its name because a colossal bronze statue of Nero stood close by, later adapted into a Sun-God. Pliny the Elder described the statue, called the Colossus, as 32 metres high and ‘breathtaking’. Because everyone knew where the statue was, it eventually became a kind of address tag for the new arena and the name stuck.

In 217 the Colosseum was badly damaged by lightning. Repairs lasted until the reign of Gordian III (238–244).

In 217 the Colosseum was badly damaged by lightning. Repairs lasted until the reign of Gordian III (238–244).

The last recorded animal hunts in the Colosseum were held in 523 by Eutharich, son-in-law of Theodoric the Great (go to Chapter 21 for details about him).

The last recorded animal hunts in the Colosseum were held in 523 by Eutharich, son-in-law of Theodoric the Great (go to Chapter 21 for details about him).

The Colosseum still stands to its full height of 50 metres (163 feet) on one side.

The Colosseum still stands to its full height of 50 metres (163 feet) on one side.

The gladiators’ barracks were right next door to the Colosseum and a large part of them is still visible today.

The gladiators’ barracks were right next door to the Colosseum and a large part of them is still visible today.

|

Figure 8-3: The Circus Maxentius. Smaller than the Circus Maximus, but the best-preserved at Rome (it’s outside the city walls by the Appian Way). |

|

People would start gathering in the middle of the night to get the best seats. No wonder the writer Pliny the Younger looked forward to race days. He hated them, but with a quarter of a million Romans busy watching the action, it meant the streets were deserted and he could get on with his work in peace and quiet.

Circus Maximus fun facts

The first stone parts were built in 174 BC.

The first stone parts were built in 174 BC.

By the first century BC, 100,000 fans could be seated.

By the first century BC, 100,000 fans could be seated.

By Nero’s reign (AD 54–68), 250,000 fans could get in, matching today’s biggest stadium: the Indianapolis Speedway (built 1909). Some believe as many as 320,000 could be crammed in later on.

By Nero’s reign (AD 54–68), 250,000 fans could get in, matching today’s biggest stadium: the Indianapolis Speedway (built 1909). Some believe as many as 320,000 could be crammed in later on.

The Circus Maximus was 594 metres (1,950 feet) long and 201 metres (660 feet) wide.

The Circus Maximus was 594 metres (1,950 feet) long and 201 metres (660 feet) wide.

The spina down the middle had a turning post at each end.

The spina down the middle had a turning post at each end.

Each race had seven laps (about 5 miles). Seven bronze dolphins on pivots at one end of the spina and seven bronze eggs at the other were used to count them.

Each race had seven laps (about 5 miles). Seven bronze dolphins on pivots at one end of the spina and seven bronze eggs at the other were used to count them.

Black gypsum flakes were scattered on the track to make it look bright.

Black gypsum flakes were scattered on the track to make it look bright.

There were religious shrines along the spina.

There were religious shrines along the spina.

The spina also had obelisks shipped all the way from Egypt to show off Rome’s mighty power.

The spina also had obelisks shipped all the way from Egypt to show off Rome’s mighty power.

In the passageways and arches under the seats, cooks, astrologers, and prostitutes catered for the fans’ other needs.

In the passageways and arches under the seats, cooks, astrologers, and prostitutes catered for the fans’ other needs.

Under Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161) overcrowding caused the deaths of more than 1,000 spectators.

Under Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161) overcrowding caused the deaths of more than 1,000 spectators.

In 2006, tens of thousands of jubilant Italians gathered here once more to watch on giant screens their nation win the soccer World Cup and celebrate afterwards.

In 2006, tens of thousands of jubilant Italians gathered here once more to watch on giant screens their nation win the soccer World Cup and celebrate afterwards.

Fighting Men: Gladiators

Easily the best-known Roman entertainment today, gladiatorial combats were one of the most extreme forms of amusing a crowd of people in history. Specially equipped and trained fighters fought bouts in matched pairs to the death. The Etruscans probably started the idea by making prisoners fight to the death during the funerals of aristocrats, but it was the Samnites who really developed gladiator fights. They depicted bouts on their tomb walls after 400 BC. The Romans even called all gladiators ‘samnites’. The first gladiator fight staged in Rome was in 264 BC when Decimus Junius Brutus made three pairs of slaves fight in honour of his dead father. It was a kind of substitute for the old human sacrifices. After that, gladiators evolved into a private form of aristocratic entertainment before becoming big-business box-office entertainment for the masses in the cities of the West and North Africa. Although amphitheatres for gladiator fights were very rare in the Eastern Empire, other venues like theatres or public squares must have been used. Ephesus in Asia Minor had no amphitheatre but the discovery of a large gladiators’ cemetery (tombstone epitaphs and wounds on bones prove it) shows that even here gladiator fights were part of local entertainment.

The gladiators: Who they were

The word ‘gladiator’ comes from the Latin word for sword, gladius, so it means literally a ‘swordsman’. The best way to get a man to fight to the death is to use a man who has nothing to lose, which is why slaves, criminals, and prisoners-of-war were the perfect candidates. If a man was really good, he might keep winning and get his freedom. On the whole, it was an offer he couldn’t refuse even though the odds were, let’s face it, not particularly good.

Slaves weren’t the only gladiators, however. Some freemen volunteered, too, especially if they were down on their luck. Nero (AD 54–68), being fairly mad and with a very individual idea of what would be entertaining, once ordered that 400 senators and 600 equestrians fight as gladiators. This was a way of humiliating them, and no doubt the Roman mob thought this was extremely funny. But the most remarkable of them all was probably the emperor Commodus (AD 180–192; Chapter 18) who was a dab hand at gladiatorial fighting (not that anyone would have dared killing him). He bragged that he had fought 735 times without getting hurt and defeated 12,000 opponents.

Schools for scoundrels

There was no point in chucking just any man into the arena. Gladiatorial combat was a crowd-pleasing activity, so the action had to be good. Only men with serious fighting potential were chosen, sent to special gladiatorial schools called ludi that were run by businessmen called lanistae. The training was tough, but gladiators were well-fed and trained to the peak of physical fitness. Pompeii had a large and well-appointed gladiator school, which was buried when Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD 79. Over 60 gladiators perished there, but evidence was also found of an unexpected perk. The remains of a rich aristocratic woman were recovered – it seems she had stopped by for a ‘visit’ so to speak, when disaster struck. It’s a reminder that successful gladiators were incredibly popular and not just for what they did in the arena.

Riot day in Pompeii

In the year AD 59, a gladiatorial contest was laid on at Pompeii by a Senator called Livineius Regulus. Rival supporters from a nearby town called Nuceria rolled up to cheer on their heroes. The locals and visitors started off by shouting at one another and then moved on to hurling stones. Soon swords were drawn, and before anyone could do anything, lots of Nucerians were being stabbed and swiped at by the Pompeians who seem to have come better equipped to cause trouble. Even women and children were cut down. The Senate in Rome was so disgusted that gladiatorial shows were banned for ten years in Pompeii as a punishment, and Regulus was forced into exile.

The fear of gladiators

Julius Caesar laid on a display of 320 gladiatorial pairs in commemoration of his dead father, but knew perfectly well it would impress people and increase his popular support. His enemies were absolutely horrified at the thought of 640 trained killers on Caesar’s payroll (640 gladiators were more than a cohort of legionaries; refer to Chapter 5 for info about the Roman army) and promptly passed a law limiting the number of gladiators that could be used at any one time. The overall result was that gladiators represented a horrible, edge-of-your-seat, rabble-rousing type of glamour.

The slave revolt led by Spartacus in 73 BC started in a gladiatorial training school – remember, these boys knew how to use weapons, had nothing to lose, and terrified Italy witless (see Chapter 14 for more about the Revolt and Chapter 25 for Spartacus).

Putting on a gladiatorial show

Gladiatorial events were publicised in advance to whip up excitement to fever-pitch on the day. One painted advertisement in Pompeii announced that a total of 30 pairs of gladiators would fight each day from 8–12 April one year, together with an animal hunt. The fights were always the big event of the day. In the Colosseum, the gladiators marched in and stood before the emperor and announced Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant (‘Hail Emperor, those about to die salute you!’).

Types of gladiators

It wouldn’t be much fun if all the gladiators were all the same, so the action was whizzed up by having lots of different types. This took advantage of the fact that gladiators might come from anywhere in the Roman Empire and had a whole array of specialised fighting techniques. Here are some of them:

Myrmillo (originally Samnis): Wore a fish-like helmet and had sword and large shield.

Myrmillo (originally Samnis): Wore a fish-like helmet and had sword and large shield.

Retiarius:

Fought with a trident and a net.

Retiarius:

Fought with a trident and a net.

Sagitarius:

Fought with a bow and arrow.

Sagitarius:

Fought with a bow and arrow.

Secutos:

Had a shield, sword, heavy helmet, and armour on one arm. Meaning ‘pursuer’, the secutores were originally based on Samnite warriors.

Secutos:

Had a shield, sword, heavy helmet, and armour on one arm. Meaning ‘pursuer’, the secutores were originally based on Samnite warriors.

Thrax:

Armed with a curved sword and small shield (the name meaning ‘Thracian’).

Thrax:

Armed with a curved sword and small shield (the name meaning ‘Thracian’).

Nor was gladiator-fighting a men-only activity. From time to time women gladiators fought. Domitian (81–96) put women into the ring, but Septimius Severus (193–211) thought that was disgusting and banned women fighting. To add to the variety, even dwarf gladiators were brought on occasionally.

.jpg)

Winner takes all

The climax of every bout was when a gladiator was down. Then it was up to the crowd. If it had been a rubbish fight, they shouted Lugula, ‘Kill him’, but if he’d fought well, they’d shout Mitte for ‘Let him go’. The final say-so went to the man who’d put the games on. If the downed gladiator was spared, the fight continued. If not, he was killed and his body dragged off so the next bouts could take place.

Meanwhile, the lucky winner got money and a palm leaf, a symbol of victory that went back to the Greeks when men competed in sport only for the honour of taking part. If a gladiator had done especially well, he got the ultimate prize: a wooden sword, which was a symbol of his freedom. Amazingly, some gladiators earned their freedom but carried on, obviously enjoying it too much. Or perhaps they’d forgotten how to do anything else.

Fighting Animals

Wild beasts were another deadly part of Roman entertainment. There’s a mosaic from a remote Roman villa in East Yorkshire in England called Rudston. It features various scenes from the amphitheatre including wild beasts. One of the lions is called Omicida, meaning ‘man-killing’ (hence our word ‘homicide’). It’s almost certainly a picture of a real, and famous, lion from an arena somewhere that the mosaicist or the villa-owner knew about. Mosaics like this were especially popular in North Africa so perhaps that’s where he came from.

Killing wild animals was the normal way to start a day at the arena. During the Colosseum’s inaugural games in AD 80, a phenomenal 5,000 animals were killed in a single day. After his conquest of Dacia, Trajan (AD 98–117) arranged in the year 107 for 11,000 animals to fight in the arena. The whole lot were killed, even though they included tame beasts. To celebrate Rome’s thousandth birthday in AD 247, the emperor Philip the Arab (AD244–249) arranged for a special display that included (amongst others):

60 lions

60 lions

40 wild horses

40 wild horses

32 elephants

32 elephants

6 hippos

6 hippos

1 rhinoceros

1 rhinoceros

Supplying animals

Of course, part of the treat was just the display of exotica, which showed off Rome’s amazing control over such a wide range of territories. Lions, rhinoceroses, and giraffes had long since disappeared from Europe, but in antiquity North Africa was a good deal more fertile than it is today. Once the Romans had control of all of North Africa, they had access to wildlife that couldn’t live there today even if the Romans hadn’t done such a good job of wiping them out.

Expeditions were sent out to capture wild animals and bring them to ports in North Africa from where they could be shipped to Rome. Of course, it was impossible to supply every arena with a constant supply of African wildlife, so probably most of the provincial arenas had to make do with less exciting animals like hares, wolves, and wild boar.

Animals in the arena

The animals were kept in cages in the Colosseum’s underground chambers and fed with cattle, or once, under Caligula, on criminals. On the day of the games, they were lifted up to the arena and sent out to do their work. Sometimes it was – literally – easy meat, especially when the entertainment on offer was the execution of criminals or other undesirables.

Although one way of having a show was simply to set animals against one another, that didn’t really make for co-ordinated and organised entertainment. To warm things up and get some serious action going, specialised animal hunters were sent into the arena to thrill the crowds. Just like gladiators, they’d been selected from the ranks of criminals, slaves, and prisoners-of-war. They were called venatores (‘hunters’), helped by bestiarii (‘animal fighters’ from bestia, ‘wild beast’), but were nothing like as popular as the gladiators.

Julius Caesar was the first to introduce a special type of bull-killing into the arena. The hunters rode horses alongside running bulls and killed them by twisting their heads with the horns. Most unpleasant.

Epic Shows and Mock Battles

These days, we make the most of great historical events by going to watch epic movies about them. In Rome, the epics came from great tales of heroic battles and myth. The most extravagant displays in the arena came from re-enactments of these great events, or were just made up for the sake of more action. They were another way of making use of the gladiators’ talents.

Julius Caesar laid on a mock battle between two armies. Each had 500 infantry, 20 elephants, and 30 cavalry. He also laid on a mock naval battle by flooding an arena and had ships brought in with two, three, and four banks of oars, each manned by a squad of soldiers. They posed as the rival fleets of Egypt and the city of Tyre. The event was so popular that people turned up from far and wide to see the spectacle, even going to the extreme of camping by the roadside to make sure of a good view on the day.

Nero staged a sea battle with mock sea monsters swimming about amongst the ships. But he had an even better idea for making himself as popular as possible. He instituted the Ludi Maximi, ‘the Greatest Games’, and organised a continuous round of free gifts all day long, ranging from 1,000 birds, food, precious metals, and jewellery right up to handing out ships, houses, and farms.

A Day at the Races – Chariot-racing

Chariot-racing was a wildly popular sport in the Roman Empire. The tradition went right back to the very beginning. Rome’s mythical founder, Romulus, is supposed to have asked his neighbours, the Sabines, to pop round and enjoy an afternoon of chariot-racing back in around 753 BC. Actually, Romulus had tricked them. While the Sabines were engrossed in the action, he got his heavies to snatch the Sabine women.

Roman chariots

Roman chariots were ultra lightweight flimsy affairs with just enough room for a man to stand on and hold the reins. In an accident, the chariot would fall to pieces in an instant and hurl the charioteer out, probably into the path of another chariot. Chariots came in (mainly) three different types:

Two-horse chariot (biga)

Two-horse chariot (biga)

Three-horse chariot (triga)

Three-horse chariot (triga)

Four-horse chariot (quadriga)

Four-horse chariot (quadriga)

The charioteers

Charioteers were generally slaves, freedmen, or charioteers as no self-respecting Roman citizen would demean himself by getting his hands dirty that way. Controlling a chariot required incredible skill and quick reactions. The more horses, the more difficult it got. Because the races went one way round the stadium, the slowest horse of the team was attached to the inside. One false move, and a chariot could either turn over or veer off across the track and hit the outside wall.

Charioteers rode for one of the four main teams: the Reds (Russata), the Whites (Albata), the Blues (Veneta), or the Greens (Prasina). And being a charioteer was a bit like being James Dean: You lived fast, hard, and generally not for very long.

Fans

The city mobs across the Roman world were fanatical supporters of chariot-racing. Supporters of each team took huge pleasure in putting the boot into rival supporters. They had plenty of opportunity, and soldiers were often on hand to try and keep order. The mad emperor Caligula (AD 37–41) was a fanatical supporter of the Greens, so much so that he would eat down at their stables and sometimes even spend the night there. He even gave one of the charioteers, Eutychus, a fortune in cash.

Like gladiators, charioteers were the big stars of the day: Aristocratic women swooned at the thought of a hulking charioteer, and some became international superstars, which explains why a few carried on racing even once they’d earned their freedom.

Chariot-racing was one of the longest-lived of all Roman sports. In the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire capital of Constantinople, long after the fall of Rome, circus supporters were still beating the living daylights out of each other whenever they could (head to Chapter 21 for information about Constantinople).

The Roman Schumacher

One of the biggest names in chariot-racing was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, who rode for several of the teams at Rome between AD 122–148. He won a fortune in prize money by coming first in 1,462 races. The total is 35 million sesterces, which, of course, is pretty meaningless today but at the time would have paid the annual wages of about six Roman legions (about 30,000 men). In other words, it was a lot of cash.

Diocles actually took part in 4,257 races which meant he took a lot of risks. His brilliant career was cut short when he was 26 and run over by a rival called Lachesis. Maybe Lachesis did it deliberately. One charioteer in North Africa cursed four of his arch rivals, begging that a demon torture and kill their horses and then crush the charioteers to death.

Pantos and Plays: Roman Theatre

Along with arenas and circuses, the average Roman city had at least one theatre and sometimes more. Just like arenas and circuses, these were originally temporary affairs. It wasn’t until the days of the late Republic that massive stone theatres were built. The origins of the Roman theatre lay firmly in the Greek East where many theatres had been built by the fourth century BC, like the one at Epidauros. But the Roman establishment disapproved of theatres, believing them to be a source of disturbances and immoral influence. In 209 BC, the Censor Cassius tried to build a theatre in Rome, but he was forced to stop by one of the consuls and general opposition.

Meanwhile, Greek influence was strong in southern Italy, so Pompeii had a stone theatre by the end of the third century BC, with an odean (a small theatre) for poetry and speeches added right next door in 80 BC. Rome’s first wooden theatre was up by 179 BC. Rome’s first certain stone version, the Theatre of Pompey, was built by 55 BC, but it might have replaced an earlier stone theatre which hasn’t yet been found. By the time of the emperors some of these theatres were really magnificent. But theatres were much smaller than the stadiums or arenas. According to Pliny the Elder, even the enormous Theatre of Pompey held at most about 40,000 spectators (less than one-sixth of the Circus Maximus), though some modern estimates come in rather lower.

Just like arenas and circuses, the theatres put on performances that were often part of religious festivals. So one thing you often find close to a theatre is a temple. That way sacred processions could start at one and end and finish at the other.

Curio’s remarkable revolving theatres

Gaius Curio, a supporter of Caesar’s during the Civil War in the first century BC, was determined to come up with an ingenious way to put on costly entertainments to win votes. He came up with two wooden theatres close to one another and each built on a revolving pivot. Two separate casts put on a performance of the same play to the same audience in the afternoon before the theatres suddenly revolved and were joined together to make an amphitheatre, at which point gladiator pairs replaced the actors. Pliny the Elder was fascinated by how Curio thought to win over swaying voters by making them sway dangerously from side to side in his rickety, lethal, revolving wooden theatres.

Theatre floor plans

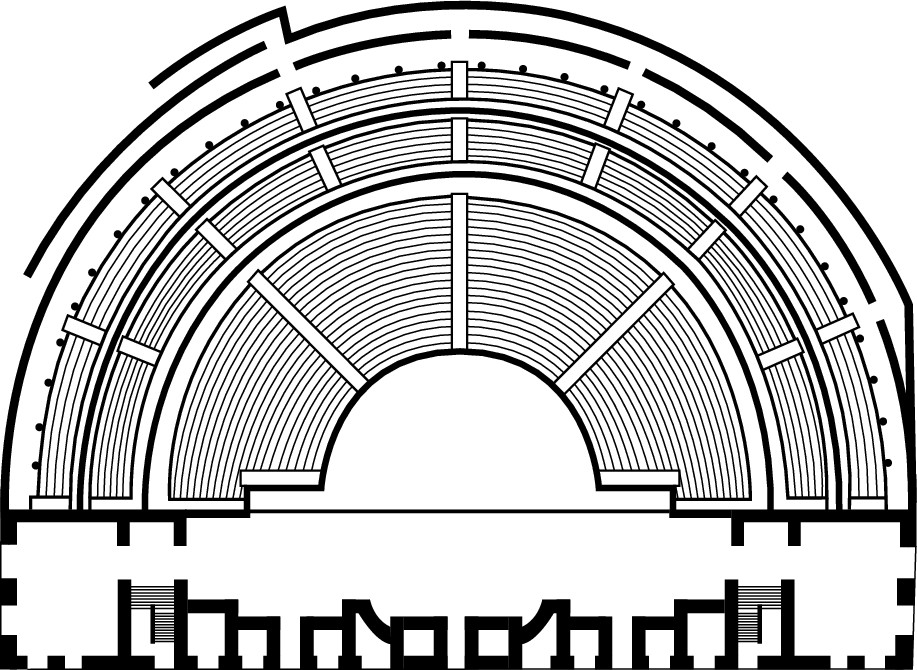

Roman theatres had three parts (see Figure 8-4): the stage, the orchestra, and the auditorium. The auditorium was semi-circular with concentric rows of seats rising up from the flat semicircular chorus area at the bottom. Whenever possible, the Romans built the theatre into a hillside that made for far less complicated building. If no hill was available, then the seating area was built on top of a series of archways, vaults, and walls. The stage faced the auditorium on the far side of the orchestra. In the most extravagant theatres, the stage had a huge wall behind it, decorated with all sorts of architectural features that helped form part of the scenery.

Roman music

No-one knows what Roman music really sounded like because the Romans didn’t write music down in a form we can understand or which survives. But music was everywhere: in the street, in markets, in religious festivals, and in the theatres. Musical contests were used to fill out interludes in the action at the circus and arena. Roman soldiers used trumpets in battle and at ceremonial displays. Other instruments the Romans knew included:

Small harps called lyrae and the more complicated cithara.

Small harps called lyrae and the more complicated cithara.

Percussion instruments like castanets, cymbals, tambourines, and the Egyptian sistrum (a kind of rattle).

Percussion instruments like castanets, cymbals, tambourines, and the Egyptian sistrum (a kind of rattle).

Wind instruments such as the double pipes, bagpipes, and flutes.

Wind instruments such as the double pipes, bagpipes, and flutes.

The water organ (hydraulus), invented by Ktesibios in the third century BC. It used a water pump to force air through the organ pipes. According to Pliny the Elder dolphins were especially enchanted by its sound!

The water organ (hydraulus), invented by Ktesibios in the third century BC. It used a water pump to force air through the organ pipes. According to Pliny the Elder dolphins were especially enchanted by its sound!

Actors and impresarios

Rich upper-class Romans didn’t think much of theatres and even less of actors. There was even a law that prohibited a senator, his son, grandson, or great-grandson from marrying a woman either of whose parents had been an actor. An actor’s social rank was so low that he was listed along with gladiators, slaves, and criminals as the men a husband could kill if his wife committed adultery with any one of them.

|

Figure 8-4: The plan of the Roman theatre at Orange in Gaul, one of the best-preserved. Most others were similar. |

|

How to find a temple – start at the theatre

Theatres often held religious performances and were closely linked to temples. The Great Temple of Diana at Ephesus in Asia Minor (Turkey) was known to have been one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World but was long lost. In 1863 the British Museum sent John Turtle Wood to look for it. He started at the theatre and followed the Sacred Way from the theatre, digging it out as he went. It led all the way to the temple, now just ruined foundations in a swamp.

The only thing that was worse was an upper-class person who did like the theatre. Caligula (AD 37–41) was especially fond of an actor called Mnester and had members of the audience beaten if they made a sound while Mnester was dancing.

There was one remarkable theatre fan and impresario called Ummidia Quadratilla who died around the early second century when she was 78. Known for being on the large size even by Roman-matron standards, Ummidia owned a troupe of pantomime dancers who acted out the part of mythological characters on the stage. In her case, the dancers were freedmen, but such dancers were usually slaves. Other upper-class Romans thought her tastes were very improper for a woman of her rank. Oddly so did Ummidia, who was convinced the shows would corrupt her own grandson and prevented him from seeing them. I call that hypocrisy.

The show must go on: Performances and oratory competitions

Plays were mostly popular amongst ordinary people who were a lot less concerned about what was ‘proper Roman entertainment’ or not-that-snotty aristocrats. Originally there were two types of theatrical performances, called ludi scaenici (‘plays on stage’): comedies and tragedies. The tragedies, like so much of the best of Roman culture, had been borrowed from the Greeks.

Roman comedies also borrowed ideas, and sometimes whole plots, from the Greeks but made the most of parodying Roman civilisation, especially by focusing on slaves as principal characters.

The Romans also enjoyed the following:

Action-adventures: The performance of a play called The Fire during the reign of Nero was like watching an action movie being made. A house was put on stage and actually set on fire. As a reward for their performance and success in escaping the on-stage action, the actors were allowed by Nero to keep any furniture they’d rescued.

Action-adventures: The performance of a play called The Fire during the reign of Nero was like watching an action movie being made. A house was put on stage and actually set on fire. As a reward for their performance and success in escaping the on-stage action, the actors were allowed by Nero to keep any furniture they’d rescued.

Re-enactments of myth: These provided plenty of opportunities for displays of flesh. A Roman writer called Apuleius described a pantomime that took place in the second century AD. It was all about the Judgment of Paris (when Paris was supposed to choose the most beautiful goddess from Juno, Minerva, or Venus). The actress playing Venus arrived on stage with nothing on apart from a piece of silk around her hips and then took part in an erotic dance with other dancers.

Re-enactments of myth: These provided plenty of opportunities for displays of flesh. A Roman writer called Apuleius described a pantomime that took place in the second century AD. It was all about the Judgment of Paris (when Paris was supposed to choose the most beautiful goddess from Juno, Minerva, or Venus). The actress playing Venus arrived on stage with nothing on apart from a piece of silk around her hips and then took part in an erotic dance with other dancers.

Mimes and pantomimes: By the end of the Republic, mime and pantomime were also performed on stage. The Romans weren’t at all averse to livening up the proceedings with live violence, sex, and nudity. Oddly, mime actors did get to speak lines, but pantomime actors didn’t.

Mimes and pantomimes: By the end of the Republic, mime and pantomime were also performed on stage. The Romans weren’t at all averse to livening up the proceedings with live violence, sex, and nudity. Oddly, mime actors did get to speak lines, but pantomime actors didn’t.

Competition oratory: One of the weirdest forms of cult entertainment for the Romans was the competition speech. Public speaking was a very important part of an educated Roman’s repertoire, and Greek-speakers who modelled themselves on the great Athenian orators of the fifth century BC (known as the ‘First Sophistic’) were the most admired. The idea was to ask the audience for speech suggestions (which could be historical themes like the great days of Athens, or more down-to-earth themes like praising baldness), and then launch off into original, spontaneous, off-the-cuff speeches to riotous applause every time they said something especially learned or witty.

Competition oratory: One of the weirdest forms of cult entertainment for the Romans was the competition speech. Public speaking was a very important part of an educated Roman’s repertoire, and Greek-speakers who modelled themselves on the great Athenian orators of the fifth century BC (known as the ‘First Sophistic’) were the most admired. The idea was to ask the audience for speech suggestions (which could be historical themes like the great days of Athens, or more down-to-earth themes like praising baldness), and then launch off into original, spontaneous, off-the-cuff speeches to riotous applause every time they said something especially learned or witty.

Theatrical performances don’t seem to have remained very popular amongst the Romans, who preferred the violent action in the arena or the thrills in the stadium. The Theatre of Marcellus in Rome was falling into ruin by the early third century AD and in the fourth century was partly demolished to repair a bridge. Thanks to theatres being associated with religious festivals, the Empire going Christian didn’t help either, though that doesn’t seem to have affected the enthusiasm for the stadium.

A Night In: Entertaining at Home

The Romans didn’t spend all their time at public entertainments. They had work to do and religious ceremonies to attend, but they enjoyed entertaining at home, too.

The best way to show off your house was at a dinner party. Dinner parties were especially popular, and it was quite common to throw one for guests who had spent the day at the amphitheatre. But the real purpose was to make a statement about who you were, who your friends were, and where you all stood in society. For example, patrons invited their clients (see Chapter 2 for an explanation of the patron-client relationship) as a kind of reward for their loyalty. As guests of lesser status, clients got inferior food and wine. But as it was customary for the host to give his guests a going-home present, attending might have turned out to be worth it.

During dinner parties, guests lay on couches round three sides of the dining room which was called the triclinium, literally meaning ‘three-sided table couch’. The idea was that slaves could bring the food into the centre through the open side so that everyone could reach out and help him- or herself. In the very richest houses, a summer dining room and a winter dining room were provided.

Dinner and a show: The entertainment

Entertainment during the party included actors performing a scene from a popular play or panto, or a display by dancers. But in the more literary households, men would bore each other stiff, and no doubt their wives, too, by reading their own poetry, which they’d composed in the style of a famous poet like Ovid or Virgil. The whole point was to show off their technical expertise at constructing verses in various different rhythms (or meters). That this could be pretty tedious is obvious from the occasion when the poet Martial promised a dinner guest an especially good time by swearing that he wouldn’t recite anything at all to his friend!

Party invite

.jpg)

‘Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On the third day before the Ides of September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me.’

It’s an astonishing little document because right out on the wilds of the military frontier, hundreds of miles from Rome and all those aristocrats lolling about on couches at luxurious feasts, a couple of soldiers’ wives (who’d probably never been to Rome) were doing their best to keep up Roman standards of entertainment and hospitality. Amazing.

Io Saturnalia!

The biggest booze-up of the year was the Saturnalia, the mid-winter festival. Starting on 17 December with a ceremony at the Temple of Saturn, it ended up lasting around a week, but for once it didn’t matter who you were. People of all classes shared tables at a free banquet as part of the festivities and shouted Io Saturnalia as a greeting – it just means ‘Wah-hay Saturnalia!’. Even slaves had a day off and were served by their masters. Gifts were exchanged, and everyone tried to have a good time, which was just as well because all the usual entertainments were closed for the holiday. Does some of that sound familiar? Yes, the Christians took over the Romans’ great winter festival and made it into Christmas, though I’d expect you’d find a lot of people who’d tell you it’s getting a lot more like the Roman Saturnalia once again.

Tableware

The very best tableware was made of gold or silver. Cups, plates, bowls, and vast dishes were all used. The most prized were those made by designer silversmiths whose individual trademarks were their own styles of decoration. Needless to say the flashiest plate was to be found in the emperor’s palace. Claudius (AD 41–54) had a slave called Drusillanus who owned a silver plate that weighed about 163 kilograms (500 pounds), and he wasn’t alone. Emperors gave gold and silver plates to their favourites.

If you couldn’t afford silver, pewter (made from tin and lead) could look like silver if it was really polished up and was a passable substitute. Then there was the pottery. Romans used loads of different types, but in a dinner-party setting, pottery was very definitely only for the lower orders, even the good stuff, which was usually a lurid red colour.

Glassware was highly prized, too, especially as it was a relatively recent innovation from Egypt. The more transparent, the more it was valued.

The menu

A collection of recipes was compiled in the fourth century and published under the name of Apicius. Many of the recipes involved adding honey, vinegar, and fish sauce, which were the main flavouring-enhancers available. But the Romans also knew about salt, pepper, mustard, and fantastically expensive spices shipped in from the Far East. Romans particularly loved a sauce called garum, which was made from rotten fermented fish. Legend has it that this fish sauce survives today in the form of Worcestershire sauce.

You can buy a translation of Apicius today and try the recipes yourself! These are some the dishes Roman dinner guests could look forward to: Guests might have a starter of lettuce with snails and eggs, barley soup, and wine chilled with snow lugged down from the mountains, or maybe pickled tuna. Main courses could be fish, pork, sow’s udders, rabbit, stuffed poultry, dormice fattened in special pots, snails so fattened with milk they couldn’t withdraw into their shells, and sea urchins.

Wine was transported in from all over the Roman world. Naturally, it was priced according to quality. Sabine wine was one of the most expensive and cost nearly four times as much as the cheapest rubbish, called ‘common wine’. Wine strainers removed impurities, and it could be drunk warm or chilled.