Chapter 12

Carthage and the First Two Punic Wars

In This Chapter

How Rome became the biggest player in the Mediterranean

How Rome became the biggest player in the Mediterranean

Why the first two Punic Wars nearly broke Rome

Why the first two Punic Wars nearly broke Rome

How Rome clung on to its allies and finished off Italy

How Rome clung on to its allies and finished off Italy

Greece falls into Rome’s lap

Greece falls into Rome’s lap

In 264 BC, Rome was nearly 500 years old. It had grown from an insignificant cluster of villages on a few hills by the river Tiber into a world-class state. Nevertheless, Rome’s expansion hadn’t been an overnight success. There were constant internal political struggles, which were still far from settled, and Rome’s wars with its neighbours were rarely walkovers.

Still, by 264 BC Roman rule was widely accepted throughout Italy. Instead of having only the resources of a city and its surrounding area to work with, Rome could call on the manpower and resources of all Italy. The Romans had done this by imposing more or less the same system of government throughout Italy. Armed with this phenomenally important asset, the Romans created a solid basis for their Empire. But like the previous 500 years, the next 250 years wouldn’t be plain sailing.

The Sicilian Story – the First Punic War (264–241 BC)

Carthage, where Tunisia is now, was a trading colony set up in North Africa by the Phoenicians of Tyre in 814 BC (in reality, Carthage was probably founded around the time that Rome was said to have been founded). Carthage was extremely successful. Its influence spread across the western Mediterranean, especially in Sicily and southern Italy, and it traded for tin probably as far as Cornwall. One story going around Rome was that the Carthaginian commander Hanno had even sailed all round Africa. It was inevitable that Rome’s rise would matter a very great deal to the Carthaginians, and vice versa.

In fact, Rome and Carthage had made several treaties in earlier times. Under the treaty of 348 BC, the Romans allowed the Carthaginians to trade slaves in Latium and recognised the Carthaginians’ monopoly of trade across the whole western Mediterranean, including Sardinia, Corsica, and Sicily. In return, the Carthaginians agreed not to set up any permanent colonies of their own in Latium. At the time, the Romans didn’t have any intention of treading on the Carthaginians’ toes. Another treaty, in 278, gave the Romans support from the Carthaginians against Pyrrhus (refer to Chapter 11).

By 264 BC, Rome was in full control of Italy. With Sicily only a few yards away, the situation was completely different. The Carthaginians saw that their wealth and power was under direct threat, while Rome’s relentless drive to expand its land and power meant their paths were bound to cross.

.jpg)

The Mamertines play with fire

Rome controlled Italy, but not all Italians were in Rome’s service. Campanian mercenaries (from south-west Italy) had been employed by Agathocles, tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily. In 315 BC, Agathocles captured the wealthy city of Messana, just a few miles from Rhegium in Italy. After Agathocles’s death in 289 BC, the mercenaries went back on their agreement to leave Sicily and out of greed captured Messana, divided it up amongst themselves, and then changed their name to Mamertines, based on their local version of Mars, the god of war, called Mamers. Not surprisingly the Syracusans were furious and attacked the Mamertines, who asked both the Romans and Carthaginians for help.

The trouble for the Romans was that, not long before, another bunch of Campanians had seized the Italian city of Rhegium, just across the straits from Messana, massacring some of the inhabitants. The Romans were disgusted by this and recaptured Rhegium. Because the Mamertines had committed more or less the same crime, the Romans couldn’t decide what to do. In the end, ever practical, they put honour on the back burner and went with what was most advantageous for them: They decided to help the Syracusans. Rome’s reasoning: The Carthaginians already controlled most of western Sicily. If the Carthaginians threw out the Mamertines from Messana, Carthage might get control of the eastern part of Sicily as well, and that would mean the Carthaginians were only a short hop from Italy.

Messana isn’t enough: Going for Sicily

In their efforts to stop the Carthaginians from claiming more of Sicily, the Romans got off to a good start. First, they used diplomacy to break up the alliance between the Carthaginians and the Syracusans. Next, they captured a Carthaginian city on Sicily’s south coast called Agrigentum and stopped the Carthaginians from sending over a bigger army.

Something changed at this point. The Romans had fallen into the Sicilian war purely because of the Mamertines in Messana. Within a year or two, the Mamertines had been completely forgotten by the Romans and the Carthaginians. The Romans saw their chance to seize all of Sicily and went to war. So began the First Punic War.

Battles and victory at sea: Becoming a naval power

Fighting the First Punic War took the Romans to a new level of military expertise because they built a naval fleet, despite having little or no naval experience, by copying the design of a Carthaginian wreck. They put the fleet under the command of Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, who trained up his naval forces. In 260 BC, although an advance force under Asina was caught out by the Carthaginians, the rest of the Roman fleet wiped out the main Carthaginian fleet off the north coast of Sicily.

The legend of Marcus Atilius Regulus

The story of Marcus Atilius Regulus (c. 310–250 BC) is fiction, but it was dreamed up to help create an image of Roman honour and self-sacrifice. The story goes that Regulus was leading the Roman army in North Africa. In 255 BC, the Carthaginians destroyed his army and captured him. They sent Regulus back to Rome to present the Carthaginians with terms for peace, on the condition that, if the Romans refused, he was to return to Carthage. Regulus went back to Rome and gave such an inspiring speech to reject the Carthaginians’ peace terms that, of course, the Romans threw the terms out. But Regulus kept his promise, returned to Carthage, and was tortured and killed. In truth, Regulus was a real man, who probably died in prison in Africa.

The Romans realised they had no idea about naval tactics. To compensate, they built portable boarding ramps, which they threw across to enemy ships; then the Roman soldiers darted across and turned what would otherwise be a naval battle into a land battle – a very successful tactic.

Attacking Sicily wasn’t going to defeat the Carthaginians for good. Rome won a second naval battle, at Ecnomus, in 256 BC using the same tactics: boarding ramps and grappling irons (iron-clawed hooks for seizing the enemy ships). The Romans invaded Africa with a huge army but were totally defeated by the Carthaginians in 255 BC, and the Roman fleet, which came to rescue survivors, was destroyed in a storm.

The struggle between Rome and the Carthaginians went on for another 14 years. The Romans suffered another naval disaster in 253 BC when a fleet was wrecked, and again 249 BC when Claudius Appius Pulcher took a fleet to destroy the Carthaginian navy in the port at Drepana. The Carthaginians moved out of the harbour before the Romans arrived. Pulcher sent his ships in and carried on sending them in even though the first ones were trying to get out again and chase the Carthaginians. In the mayhem, 93 out of 120 Roman ships were lost.

For some bizarre reason, despite having defeated the Romans at sea, the Carthaginians decided to take their ships out of service, completely unaware that the Romans had been busy building a new fleet, paid for by voluntary loans. In fact, they’d built two – the first was wrecked in yet another storm, but they promptly set to and built another.

Faced with this sudden resurgence of Roman naval power in 242 BC, the Carthaginians were totally wrong-footed. A new Carthaginian fleet had to be thrown together in double-quick time. In March 241 BC, the Roman fleet met the Carthaginian fleet off the coast of Sicily, and the Romans totally defeated the Carthaginians and occupied Sicily. The Carthaginians executed their admiral, Hanno, and were forced to abandon their claims to Sicily and pay compensation for the war!

Setting the stage for the Second Punic War

The Romans made a lot of mistakes in the First Punic War but they won because:

They had so much manpower they could afford losses.

They had so much manpower they could afford losses.

They learned new methods of warfare from their enemies.

They learned new methods of warfare from their enemies.

They kept coming back for more battle even when they had setbacks.

They kept coming back for more battle even when they had setbacks.

After defeating the Carthaginians in Sicily, the Romans realised that Carthaginian trading wealth was up for grabs. With Carthage defeated, the Romans followed the war up by capturing the islands of Sardinia and Corsica, preventing the Carthaginians from having handy bases from which to launch assaults on Italy’s west coast.

The Carthaginians, having lost Sicily, decided to make up for the loss by building up their control in Spain – a decision that led directly to the Second Punic War.

Staying busy in the interim: Capturing northern Italy

With the First Punic War out of the way, and before the Second Punic War broke out, the Romans had to deal again with the Gauls of northern Italy.

The Gauls of northern Italy last invaded central Italy in 390 BC. They’d sacked Rome but went home with a huge ransom, rather than troubling themselves to take the opportunity to destroy Rome once and for all. The Gauls were a thorn in the flesh of the Romans for much of the next century, and the Gauls even took part in the Third Samnite War (refer to Chapter 11 for details about the Gauls). Major defeats of the Gauls took place in the 280s, and a Roman colony was planted on the edge of Gaulish territory near the site of modern Ancona, in northern Italy. In 279 BC, an army of Gauls was defeated by the Greeks at Delphi in Greece.

It took more than 50 years before the Gauls finally forgot about these setbacks and for a new generation of have-a-go warriors to grow up, determined to earn themselves reputations as heroic fighters. These new Gaulish warriors joined up with other tribes from farther north and sent an army of 70,000 into Italy. Big mistake. By now the Romans had the whole of Italy at their disposal and had no trouble in sending an army nearly twice as big against the Gauls.

The Gauls were soundly defeated and the Romans decided that the best thing to do was conquer northern Italy and end the chances of another Gaulish comeback. Not that that was a difficult decision to make. Just as the First Punic War opened Roman eyes to the chances of seizing the Carthaginians’ wealth, so the Gaulish invasion of 225 BC made the Romans see the attraction of holding the fertile northern plains of Italy, abundant in woodland, corn, and livestock.

Unbelievably, the Romans took just three seasons of campaigning to capture the whole of northern Italy and push the Gauls back. They built new roads and set up naval bases in the region. By 220 BC, the Romans held an area almost identical to modern Italy and controlled the whole area from the Alps to the southernmost tip of Sicily.

The Second Punic War (218–202 BC)

The Carthaginians had been well and truly bruised by the First Punic War. The loss of the rich island of Sicily made a big dent in their wealth. Their damaged prestige meant other peoples under their control tried to throw them off. To bolster Carthaginian power and reputation, the Carthaginians decided to build up their control in Spain.

Hamilcar Barca, a Carthaginian general who was busy suppressing revolts in North Africa, was the ideal man for the job. He’d spent a lot of time fighting the Romans in Sicily in the First Punic War and resented the Romans from the bottom of his heart.

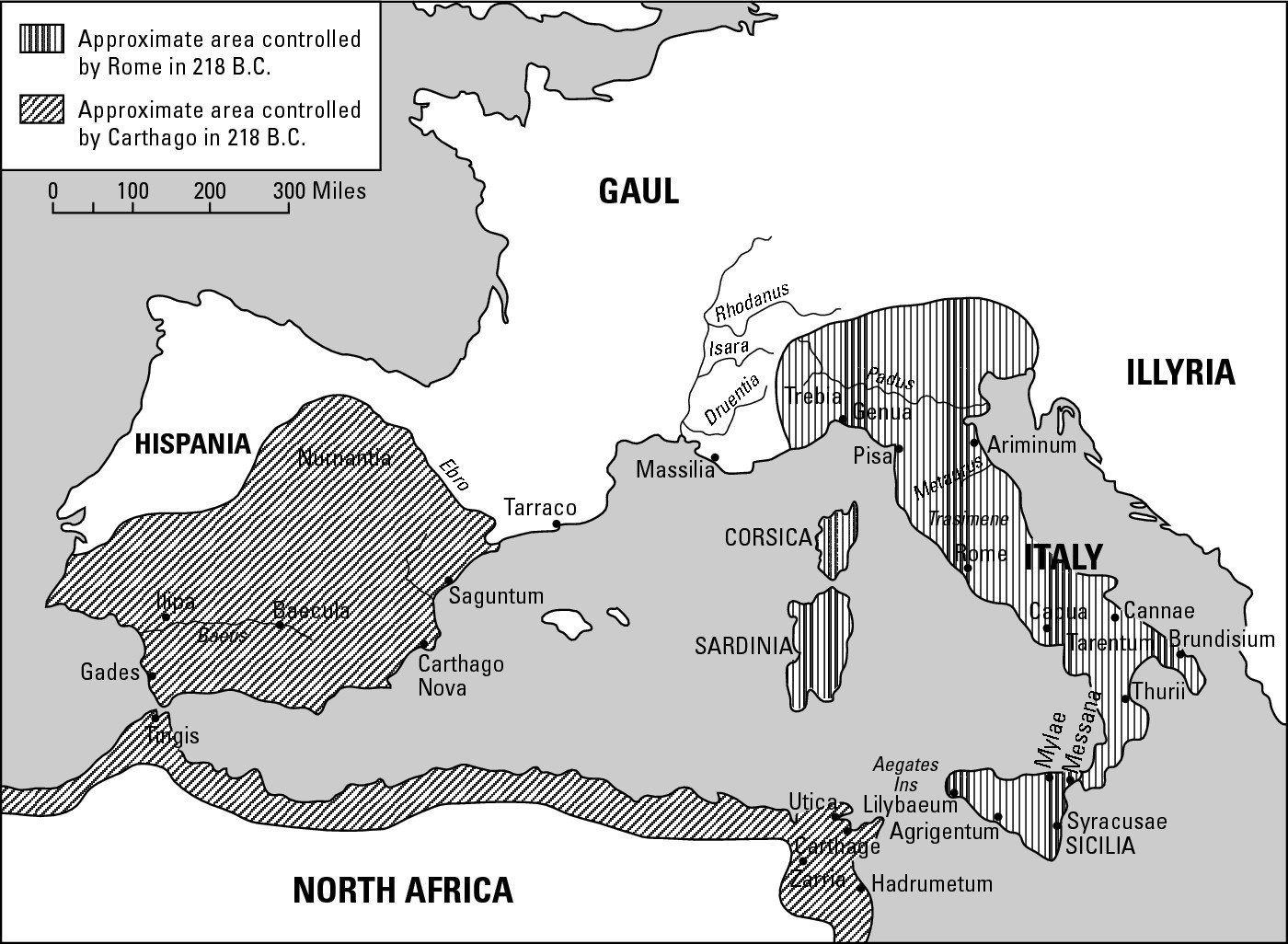

Hamilcar set up new Carthaginian bases in Spain, including Nova Carthago (‘New Carthage’ – modern Cartagena). Hamilcar’s work was carried on by his son-in-law Hasdrubal, and then his son Hannibal. The Romans didn’t like what Hamilcar was doing one bit and demanded that the Carthaginians stay south of the river Ebro in north-east Spain. Figure 12-1 shows the territory controlled by the Rome and Carthage in 218 BC when Hannibal crossed the Alps into Italy in the Second Punic War.

The Carthaginians did, indeed, stay south of the river Ebro. Unfortunately for the Carthaginians, in ‘their’ area was a coastal city called Saguntum, a Roman ally (refer to Figure 12-1). A Roman delegation was sent to New Carthage to warn the Carthaginians to leave Saguntum alone. Hannibal (Hamlicar’s son) took no notice and besieged Saguntum in 219. The city fell after eight months because the Romans were too tied up with Illyrian pirates to help (see the section ‘Trouble in the East: The Macedonian Wars’ for that bit of history), but by 218, Rome had defeated the Illyrians and were free to deal with the situation in New Carthage.

Rome sent a deputation to Carthage to demand that Hannibal be surrendered. The Carthaginians naturally said no and told the Roman deputation to offer them peace or war. The Roman envoys offered war and the Carthaginians accepted, which was a decisive moment in history.

The amazing march of elephants

The Carthaginian forces in Spain were miles from home and the Romans controlled the sea. The Roman plan was to use their navy to send an army to fight Hannibal in Spain. Hannibal had other ideas.

Hannibal realised that, by marching into Italy overland, he could dodge the Roman navy. In 218 BC, Hannibal crossed the Alps with his army and his elephants. The Roman force turned up too late to stop him. Hannibal was immediately joined by the Gaulish tribes who were delighted at the chance to have another go at Rome, especially as it looked as if the Romans were going to lose (refer to the earlier section ‘Staying busy in the interim: Capturing northern Italy’ for information on the Gauls of northern Italy).

|

Figure 12-1: The areas involved in all three Punic Wars. |

|

There’s no certainty about how big Hannibal’s army was. The lowest estimate was 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry as well as 21 surviving elephants, but Hannibal lost a large number of men along the way (and about 40 elephants). Some of the army had refused to make the journey, while he was said to have lost 36,000 men alone after crossing the Rhône.

The Battle of Lake Trasimene – 217 BC

Despite the losses on the way, Hannibal’s army was unstoppable. He fought off a Roman army in northern Italy, and the Romans fell back. The Romans thought Hannibal would come into Italy down the main road called the Via Flaminia. He didn’t – he sneaked in through an unguarded mountain pass, forcing a 25,000-strong Roman army under Caius Flaminius to chase after him. Flaminius, and a large part of his army, were promptly wiped out on the banks of Lake Trasimene.

What happened at Lake Trasimene was a classic ambush. As Flaminius’s force travelled by on a narrow road, warriors hurtled down the hills on either side, while cavalry attacked from behind. The ambush happened far too quickly for Flamninius to organise the Roman troops into their battle lines – the formation in which the Roman armies fought best. Out of formation, all their careful discipline and tactics collapsed. Being taken by surprise was a catastrophe. Of the 25,000 Roman soldiers, more than half were killed.

Trasimene was a brilliant success for Hannibal, and also handy for his men, who now re-equipped themselves with Roman weapons and armour. But Hannibal’s plan started to go wrong.

Catastrophe at Cannae – 216 BC

Rome’s genius had been getting allies on their side and keeping them there. So when Hannibal defeated the Roman General Flamninius at Lake Trasimene and then hoped the allies would come over to him and swell his army, he was wrong. Luckily for Rome, they didn’t, and that meant all Hannibal’s hopes of being supplied by grateful Italian cities vanished. So Hannibal bypassed Rome and tried his luck in southern Italy. The cities of the south wouldn’t help him either.

At this point in the Second Punic War, Hannibal really ought to have been defeated. He wasn’t able to get the help from the Roman allies that he had counted on, and by 216 BC, he had at the most about 40,000 to 50,000 men. But the Romans made a disastrous mistake. They thought that, by having a huge army, they would crush Hannibal easily. They massed an army of 50,000 and put it under the command of two Roman consuls who had no idea of Hannibal’s strategy or tactics. Worse, the two consuls constantly argued, and the army threatened mutiny. Not the best way to prepare for a battle that could cost the Romans Italy. The situation was a recipe for disaster.

The Romans found Hannibal at Cannae, about 180 miles south-east of Rome. Initially, the battle went well for the Romans. They threw their main force in on the Carthaginian centre, which was made up of Gauls and Spaniards. Then the Gauls and Spaniards fell back, and the Romans found themselves trapped between the Carthaginian wings of African infantry and cavalry.

The Carthaginian wings moved in on the now-exhausted Romans and totally defeated them. One estimate put the Romans losses at 45,500 infantry and 2,700 cavalry; another put it as high as 70,000. The point is that the Roman army was wiped out, but Hannibal only lost about 6,000 troops.

Bloody and bruised, but still swinging

It hardly needs saying that after Cannae, the Romans faced total and utter ruin. Up to this point, they’d lost possibly as many as 100,000 men in Hannibal’s campaign. Now Rome’s allies started to defect. Capua changed sides, lured by the prospect of Rome’s collapse and the chance of becoming the chief city in Italy. Overseas, places like Sardinia, Spain, and Sicily also started simmering with rebellion. One of history’s great truths is that whenever a powerful state starts to look like a loser, even the most loyal friends look to the winner.

Hannibal’s gamble about the Roman allies joining him didn’t pay off, and most stayed loyal to Rome. Hannibal also found that Rome’s persistence – even in the face of humiliating adversity – was beyond his ability to wear down. By means of heavy taxation and military conscription, Rome now threw its resources into winning the war. That included knocking out Hieronymus of Syracuse in Sicily who thought Cannae was such a brilliant victory he was easily persuaded by the Carthaginians to join in on their side in return for half of Sicily. Even though he was soon murdered by Syracusans to prevent this, they were so horrified by Roman brutality they ended up renewing the alliance with Carthage and faced an invasion by the Roman general Claudius Marcellus. The city fell in 211 BC (see Chapter 5 for the remarkable story of its defence by Archimedes against the Roman navy).

In 211 BC, Rome recaptured Capua despite Hannibal’s threat to invade Rome. Rome punished Capua by lowering its status and confiscating much of its land. In 209 BC, Rome recaptured Tarentum, another defector.

When the Carthaginians sent another army from Spain to reinforce Hannibal, the Romans put together another vast army under Caius Claudius Nero. Nero’s army headed off the Carthaginian reinforcements before they joined Hannibal. In 207 BC, the new Carthaginian army was totally defeated at Metaurus and its commander, Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal, was killed. Just to add insult to injury, Roman cavalry threw Hasdrubal’s severed head into Hannibal’s camp, which was a double shock to Hannibal, who hadn’t even known that Hasdrubal had reached Italy. The game was up for Hannibal: It was obvious that despite Trasimene and Cannae, he had completely failed to capture Rome or any other Roman cities, or defeat the Romans decisively. Amazingly, the Senate wrote Hannibal off as a spent force, and he managed to hide out in the toe of Italy for four years before escaping back to North Africa to face the Romans again.

Scipio in the nick of time

Publius Cornelius Scipio was a Roman aristocrat and brilliant soldier who’d cut his teeth in the Second Punic War. He’d certainly been at the Roman defeat at Cannae and was probably at Trasimene, too. Although he was a young man – too young to be consul – he had bucketloads of military experience.

In 210 BC, Scipio was sent with an army to fight the Carthaginians in Spain. In 209 BC, taking advantage of the fact that the Carthaginians thought the Romans were a spent force in Spain and had divided their forces, Scipio captured New Carthage, the Carthaginian capital in Spain. He followed this up with a major victory against the Carthaginians at Ilipa in southern Spain in 206. With the Carthaginians knocked out of Spain, Scipio then turned to the main event, the attack on the Carthaginian homeland itself: Africa.

Meanwhile, back home in 205 BC, Scipio became Consul, despite being technically too young (the usual minimum age was 42) and was also made governor of Sicily, the perfect launch pad for an invasion of Africa. Scipio bided his time, planned the campaign to invade Africa, and made sure he had a first-class army to deliver the final blow. Scipio invaded Africa in 204 BC and set about destroying Carthaginian armies. The Carthaginians initially sued for peace, but when Hannibal came back from Italy to fight Scipio, the peace talks were abandoned.

The Battle of Zama – 202 BC

Hannibal and Scipio met at the Battle of Zama in North Africa in 202 BC. Sheer force of numbers, especially cavalry, rather than brilliant tactics, won the day for the Romans. Even so, Scipio did exactly what Hannibal had done at Cannae: He surrounded the enemy and trapped them. Hannibal surrendered, and the peace terms left the Carthaginians powerless:

Their navy was cut down to ten ships.

Their navy was cut down to ten ships.

Their ally Numidia was made independent and an ally of Rome.

Their ally Numidia was made independent and an ally of Rome.

They lost their possessions outside Africa.

They lost their possessions outside Africa.

They had to pay 800,000 pounds of silver to Rome over 50 years.

They had to pay 800,000 pounds of silver to Rome over 50 years.

They could not wage war without Rome’s permission.

They could not wage war without Rome’s permission.

Nonetheless, Carthage got over its defeat and eventually became a wealthy power again. Next time round, Rome’s revenge would be total and permanent (see Chapter 13).

Scipio, little more than 30 years old, returned to Rome at the peak of his fame and popularity. He had saved Rome from its greatest enemy and recovered Rome’s pre-eminence in North Africa. He took the name Africanus and celebrated with great triumph (for more on Scipio see Chapter 23).

Trouble in the East: The Macedonian Wars

Until the end of the Second Punic War in 202 BC, most of Rome’s attention had been focused on Italy, the Carthaginians, and Spain. The Illyrians, people in what is now Albania and the former countries of Yugoslavia, had caused trouble before the Second Punic War, but the trouble had only been a side show (you can read the tale in the section ‘A bit of background: Philip V and Illyrian pirates’). After Philip V of Macedon got involved with the Carthaginians and Seleucids, Rome could not stand by because the campaign against Philip took Rome on a punishing journey east into Greece and beyond and eventually led Rome to conquer vast tracts of territory there: so it was a decisive moment. In 500 years, the Eastern Mediterranean region (including modern Greece, Turkey, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Syria, Israel, and Egypt) was to become the home of what was left of the Roman Empire (see Chapter 21).

A bit of background: Philip V and Illyrian pirates

Between the First and Second Punic War, the Romans found themselves facing a problem with the Illyrians (Illyria is the coast of what used to be Yugoslavia down to Greece). This bit of trouble prompted the Romans’ first foray eastwards.

The Illyrian tribes were professional pirates who made an excellent living out of stealing the valuable cargoes of merchant ships in the Adriatic. Their leaders encouraged and helped organise the piracy. In 231 BC, under their King, Agron, the Illyrians had been working as mercenaries for King Philip V of Macedon and had saved the city of Medion, under siege from a force of Aetolians (from an area farther south in Greece).

Following this victory, King Agron of the Illyrians died (he literally drank himself to death while celebrating), and his queen, Teuta, got it into her head that the Illyrians could do as they pleased. She declared that all other states were enemies and that the Illyrian navy must attack anyone and everyone. The Romans decided enough was enough. In 229 BC a diplomatic mission was sent to the Teuta. One of the ambassadors was murdered, so Rome sent a fleet over to sort the Illyrians out. Teuta immediately offered to give in, but the Romans didn’t trust her and went to several Greek cities on the Adriatic coast and offered them protection in return for practical support. It was a brilliant gesture – Rome got a foothold across the Adriatic but without looking like a conqueror.

One of Teuta’s supporters, Demetrius from the island of Pharos, went over to the Romans and was promptly made a Roman amicus (‘friend’). As a result, other great Greek cities like Athens and Corinth also welcomed Roman diplomatic missions. But Demetrius blew it. Sensing the Second Punic War was brewing, he decided to return to piracy and attack the very Illyrian cities that were now loyal to Rome. Another Roman fleet was sent over in 219 BC, and Demetrius fled to Philip V of Macedon. He tried to get Philip to attack the Romans, but Philip held back.

Now back to the story.

The First Macedonian War (214–205 BC)

Just before the Second Punic War broke out in 218 BC, Rome had been trying to end the problem of the Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic. One of the players in the drama was Philip V, King of Macedon (refer to the preceding section). Philip was an opportunist. After the catastrophe at Cannae and with the impression that the Second Punic War was going against the Romans, Philip decided to make friends with Hannibal, at the time the new kid on the block in Italy (remember, this happened before Hannibal’s final defeat). This was obviously a situation that Rome had to deal with, and so began the First Macedonian War.

Because the Second Punic War was using up almost all Rome’s resources, the First Macedonian War didn’t amount to much. Rome made an alliance with Philip’s enemy, the Aetolian League led by its ally, the great Greek city of Pergamon on the west coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), then ruled by Attalos I (241–197 BC). The Aetolian League was a confederation of cities in central Greece formed to oppose the Macedonians. A bit of fighting took place, but in 205 BC, the Romans made peace with Philip, who had now wised up to the fact that Rome was likely to win the Second Punic War.

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC)

Philip, ever the opportunist, came up with another plan, one that he hoped would avoid attention from Rome. With support from the Seleucid Empire in Syria, his idea was to start attacking the Egyptians, then ruled by the boy-Pharaoh Ptolemy V, and to help himself to Egyptian possessions. The Seleucid Empire was formed in what is now Syria, Iran, and Iraq, by Seleucus, one of Alexander the Great’s generals, out of Alexander’s empire on his death in 323 BC. It had fallen into decline, but Seleucus’s descendant Antiochus III revived its fortunes.

Thanks to the fact that Philip’s forces attacked whoever they pleased in the Aegean, the Greeks got annoyed with him. Determined to protect its interests, the wealthy island of Rhodes made an alliance with Pergamon. In 201 BC, Pergamon and Rhodes turned to Rome for help after Philip’s navy beat their combined forces.

Rome was exhausted and reluctant to go to war again. But when the news got out that Philip was in alliance with the Seleucids, led by the ambitious Antiochus III ‘the Great’ (242–187 BC), they decided they had no choice. Antiochus III had helped himself to Syria and Palestine. The Romans decided to make the war look as if it was as a campaign to protect the freedom of the Greek cities.

The Second Macedonian War started when the Romans arrived in Illyria in 200 BC under the command of Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Frankly, the war got off to a slow start and stayed that way. The Romans tried to wear Philip down. Philip couldn’t let that happen, so he forced a pitched battle by a ridge at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. Racing down the hillside, Philip nearly demolished the Roman army, but Flamininus counter-attacked with his wing before the second wave of Macedonians had time to get into position. Philip was totally defeated.

The Greek cities were delirious with joy at their deliverance from Philip. At the Isthmian Games in Corinth in 196 BC, the Roman commander Flamininus proclaimed all Greece to be free. The Greeks were particularly impressed because Flamininus gave his speech in Greek. The Greeks decided that the Romans were thoroughly good types and their saviours and patrons, while the Romans indulged themselves in their love of Greek art and culture. But Greece remained a problem, and more to the point so did Antiochus III. What happened to Greece comes next (see Chapter 13 for the story about Antiochus III).

The Greek effect

The Romans had been fascinated by all things Greek for a long time. The Etruscans (read about them in Chapter 10) had picked up a lot from the Greeks. King Tarquinius Priscus once sent his sons to the oracle in Delphi for advice. As Rome’s tentacles spread across the Mediterranean in the second century BC, the Romans became more and more impressed by the sophisticated Greek culture. Greek statues were brought to Rome and widely copied. Greek gods were matched with Roman gods. Greek literature was read and appreciated. The Roman playwright Terence (c. 190–159 BC) was translated and adapted into Latin works by the Greek playwright Menander and others for a Roman audience. The Greeks went on to influence Roman culture for centuries (see Hadrian in Chapter 17, for example).

The Third Macedonian War (172–167 BC)

Philip V of Macedon died in 179 BC. The throne went to his anti-Roman son Perseus who had had his pro-Roman younger brother Demetrius executed. The Romans declared war in 172 BC on the pretext that Perseus had attacked some Balkan chieftains who were Roman allies. Perseus failed to take advantage of the general Greek back-pedalling about their love for Rome, but he still managed to defeat the Romans in 171 BC. It was the same old story – the Romans were all the more determined to beat him. It took three more years of campaigns, but at Pydna in Macedonia in 168 BC, Perseus was crushed by the Roman army commanded by Lucius Aemilius Paullus. Perseus might have won if the Achaean League had formed an alliance with him. They certainly thought about it – until the Romans seized some key Achaean hostages to keep them on good behaviour.

After Perseus was defeated, the Romans decided they’d had enough of the Greeks and their internal disputes. Around 1,000 supporters of Macedonia in Greece were shipped to Italy for trial – 700 died in prison. In 167 BC, the region of Epirus was ravaged, and 150,000 people were sold into slavery. Macedonia was broken up into four republics.

Even so, the Romans didn’t have any plans to conquer and govern the Greeks. The idea was to leave the Greeks free, but punish them so they’d never ally themselves with another enemy of Rome. The Romans even cut taxes to make themselves look like thoroughly reasonable people.

It’s not really surprising that Greece wasn’t Rome’s greatest concern at this time. Between 151–146 BC, the Third Punic War was raging. More on that in Chapter 13.

The spoils of Greece (Achaea)

Despite Rome’s plan to just punish, but not conquer, the Greeks, the last straw came with Andriscus, a pretender to the Macedonian throne claiming to be a son of Perseus, who managed to reunite Macedonia. The Romans abandoned the idea of leaving the Greeks free.

The sack of Corinth

According to the Roman geographer Strabo, Corinth was sacked partly by the Roman general Lucius Mummius because of the Corinthians’ disgusting habits, such as pouring filth on top of any Romans passing by. But the main reason was to punish the city for its resistance and to wipe out a major commercial rival. The men were all murdered, and women and children enslaved. According to the Greek historian Polybius, Mummius was placed under huge pressure to be so cruel and didn’t have the strength to stand up to it. He helped himself to Corinthian works of art, which were shipped back to Rome, including a painting of Dionysus which ended up in the Temple of Ceres. Polybius, who was there, watched with disgust as soldiers played dice on paintings they had chucked on the ground. A century later Julius Caesar founded a colony on the site of Corinth. The Roman colonists dug up the ancient Corinthian cemeteries and made a tidy living out of selling the terracotta reliefs and bronze vessels they found.

By 148 BC, a Roman army under Quintus Caecilius Metellus drove Andriscus off (sometimes called the Fourth Macedonian War). The Achaean League appointed Critolaos of Megalopolis their general. Refusing to negotiate with the Romans, he overran central Greece with his army. Metellus dealt with him, but Achaeans making a last stand near Corinth was destroyed by the Roman Consul Lucius Mummius.

Corinth was razed to the ground. The Achaean League was broken up. The Roman governor of Macedonia watched out for trouble, and Greece was forced to pay tribute to Rome. It was a turning point in Greek history that mirrored what had happened in Italy between 493–272 BC when the Romans systematically took control of Italian cities (refer to Chapter 11). Now the Greek city states lost their freedom; centuries of conflict, war, and destruction followed, with periods of brilliance in politics and art.

The Secret of Success: The Comeback

The Roman army didn’t have a great deal of flair, but it was successful because it had a ready supply of manpower from the allies, it was the best organised, and it worked like a machine. Every soldier knew what his job was and where he was supposed to be, whether that was in camp or on the battlefield.

The setting up of colonies to guard ports, mountain passes, or major road junctions meant there was a Roman presence in crucial locations, acting as a military reserve. That colonies were laid out as if they were military camps, with institutions modelled on those in Rome, was part of the process.

Towns in allied territory continued to function much as they always had, but now under Roman supervision. All across Italy, communities found that being in Rome’s orbit could be a big plus. In return for contributions to the Roman army, they received a share in the spoils of victory. The allies also benefited from stability, but without being oppressed. The Sabines, for example, had fought the Romans on four separate occasions, but instead of finding themselves sold into slavery and their settlements confiscated, by 268 BC they had been promoted to Roman citizens with full voting rights.