VIET NAM TIME TRAVEL, 1970–2013

JUDY GUMBO

—“Here’s to the State of Richard Nixon,” Phil Ochs

I am one among millions of people around the globe who protested the war in Viet Nam. I am also one of perhaps 200 people from the United States who visited Viet Nam while the war still raged. I was born Judy Clavir in Toronto, Canada, on June 25, 1943, and raised a “red diaper baby,” or child of Communist Party parents. I am perhaps best known as an original member of the Yippies, or Youth International Party, a late 1960s political and countercultural group dedicated to performance activism. In late 1967, I emigrated from Canada to Berkeley, where I met Stew Albert, who became my lover and partner of 40 years. Luckily for me, Stew also happened to be a close friend of both Yippie founder Jerry Rubin and Black Panther Party leader Eldridge Cleaver, who gave me the name Gumbo since, in his mind, Gumbo went with Stew. I, along with Stew, Nancy Kurshan, Jerry Rubin, Abbie and Anita Hoffman, Paul Krassner, and folksinger Phil Ochs Were among the 10,000 people tear-gassed in Chicago in August 1968 when the Yippies ran a pig named Pigasus for president to protest the war.

Nancy Kurshan, Genie Plamondon, and Judy Gumbo protest outside the U.S. embassy in Moscow, 1970.

Photo courtesy of Judy Gumbo.

By the end of 1968, public opposition to the war had become a fact of American life. More than 14,500 young American soldiers had been killed. More than 485,000 U.S. military personnel had served in combat. Even though President Lyndon Baines Johnson had by then been replaced by President Richard Nixon, a claim by Johnson’s top general Curtis LeMay that the United States would bomb Viet Nam back into the Stone Age still resonated. Pro-war America labeled Vietnamese people as gooks; demonizing combatant and civilian as a slant-eyed, black-pyjama’d enemy who fought relentlessly by day and insinuated themselves at night into tunnels, encampments, and nightmares of foot soldiers and presidents alike. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of antiwar activists like me looked on North Vietnamese freedom fighters and their compatriots, the NLF (the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, or Viet Cong, as the media liked to called them) as Davids battling the high-tech killing machine of the American Goliath. By the time I visited what was called North Viet Nam in 1970, U.S. troops had been waging war in that country for six years.

I remember myself from those days: curly brown hair to my shoulders; a red, blue and gold NLF flag painted on one cheek; orange woman’s symbol on the other; green marijuana leaf on my chin, speaking into a microphone in my best take-no-prisoners’ voice: “Richard Nixon and his arrogant pig generals are traitors to America. They betray the American people by invading and bombing Vietnam. Vietnam has a 1,000-year history of defeating foreign aggressors. The Vietnamese will win. All the American war machine does is condemn young people like us—and millions of Vietnamese—to death. I belong to a New Nation. We believe in peace, justice, sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Youth will make the revolution! Yippie!”

The American War in Viet Nam would come to an end in 1975, making it, for its day, the longest war in U.S. history. By then, an estimated two million Vietnamese civilians had died, plus another one million combatants—10 percent of their entire population. Fifty-eight thousand Americans, primarily young men, many drafted against their will, also perished—.00027 percent of the population of the United States in 1975. As our guide to Viet Nam’s Cu Chi tunnels told us in 2013, “We didn’t win the war. You can’t say anyone won the war. We lost three million people.”

I arrived in Hanoi in May 1970, along with Nancy Kurshan and Genie Plamondon of the White Panther Party. We were a Yippie women’s delegation. Our goal was to bring back to our respective cohorts what we discovered about the consequences of war. Three weeks before our departure, on April 30, 1970, the world had learned that U.S. and South Vietnamese Army troops invaded Cambodia, a neutral nation and Vietnam’s next-door neighbor. It did not cross my mind to cancel our trip. The antiwar chant “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win” was not, to my way of thinking, propagandistic wish fulfillment—Vietnamese victory was, I felt, inevitable.

On our way home from Viet Nam in 1970, Genie, Nancy, and I, dressed NLF-style in black “pyjamas” and conical straw hats, held an antiwar demonstration outside the U.S. embassy in Moscow. I also carried with me 143 letters from American pilots who had been shot down and captured. This unorthodox route was, at the time, the only reliable way for uncensored mail from servicemen detained in Viet Nam to reach their families. It would take three more years of intense carpet bombing of North Viet Nam, Cambodia, and Laos, plus continued Vietnamese resistance combined with increasingly large and militant demonstrations in the United States, for President Nixon’s secretary of state Henry Kissinger and Special Advisor Le Duc Tho to sign the Paris Peace Accords. They did so on January 27, 2003. Two years later, on April 30, 1975, Saigon became a liberated Ho Chi Minh City.

In 2013, I returned to Viet Nam as part of a delegation of nine former antiwar activists, plus spouses, partners, and supporters, invited to help celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords. I had been ridiculously nervous before the trip. I put it down to fear of losing my illusions. I could not help but ask a selfish question: Would this country for which I once held the most romantic of ideals still maintain their moral hegemony in a brave new world of Starbucks and a Ho Chi Minh City stock exchange?

1970: The Munitions Factory

A dilapidated dark green school bus with the number 4709 stenciled on its windshield waited for Nancy, Genie, and me on Ngo Quyen Street outside the Reunification Hotel, the former colonial French Hotel Metropole. As did Do Xuan Oanh, the man who had invited the three of us to visit Viet Nam. Oanh, pronounced “Wine” with a nasal intonation and “nnnng” at the end, was more than just the go-to person for visiting anti–Viet Nam War activists. Oanh was a composer, a poet in the romantic Vietnamese/ French style, a watercolor artist, and a translator of Mark Twain’s Huck Finn into Vietnamese. Everyone from the inner core of the U.S. peace movement knew him. The literary icon Susan Sontag put it this way: Oanh had a “personal authority, (he) walks and sits with that charming ‘American’ slouch, and sometimes seems moody or distracted.”1 I would come to recognize that moodiness. If I had to guess, I’d say Oanh’s brooding stemmed from the fact that his wife, the granddaughter of the chief of staff of the French government in Indochina, had been arrested in the early 1950s and held at the Maison Central, a concrete building in downtown Hanoi that would become known as the infamous Hanoi Hilton. Oanh told me in 1970 that his wife suffered chronic headaches and would pass out every time she saw a snake. It would take me to 2013 to grasp the implication of Oanh’s story when I saw on the wall of the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City a depiction of a woman being held down by two burly, bare-chested men who raped her with a snake.

In 1970, our bus drove Nancy, Genie, me, Oanh, and three Vietnamese guides, two men and a woman, three hours south until we crossed the Ham Rong Bridge in Thanh Hoa province. To me, the bridge did not resemble a bridge at all, instead it looked as if a deranged spider had spun a web out of steel girders, gouged and pitted. A hole in the bus’s rusted floor allowed a view of brown muddy river water rushing by mere yards under my feet. Oanh told us the North Vietnamese army moved war materiel by train, oxcart, bicycle, and foot across this bridge to the South. American planes had made at least 400 sorties, laying down a carpet of bombs. “Every day this bridge is demolished.” I recall Oanh saying. “Every night it is rebuilt. The courage of the peasants is a local legend.”

I could not fathom living such a life. Before I could find words to respond, I saw a mountain loom on my right. At its base, railway cars lay in a graveyard of rusting brown. One-half of the mountain’s top had been sheared away; as if some industrial-sized backhoe had strip-mined giant bites from it. I made out the words “QUYET THANG” carved into the mountaintop in letters of white chalk. I asked Oanh what the words meant. Oanh replied.

“Determined to win. So American pilots will see this as they fly over.”

Thoroughly cowed, I did not think to question why the Vietnamese believed American pilots could translate this slogan. Then I realized mine was an Americo-centric point of view. The slogan was much more to inspire resistance among peasants undergoing bombing than a deterrent to pilots. By the time the bus stopped, I was feeling no small measure of guilt and remorse, as if I was in some way responsible for the destruction I had witnessed.

A woman in a stained lightweight patterned shirt, visibly pregnant, led us through a narrow passage into a dark low-ceiling cave hollowed into the mountain’s core. Bare bulbs attached to wires flickered orange; tons of black mountain earth above us tamed Vietnam’s humidity and heat. Seven or eight women and men bent over lathes that resembled oversized sewing machines. Oanh said that despite daily bombings, this munitions factory had remained in continuous production. I shivered, not from fear or from my cooling skin but because the air around me felt infused with such resolve I could not help but sop it up like a sponge. Suddenly the machines stopped. The cave fell silent. I heard water dripping with a faint ping ping. The pregnant woman began to chant, bird-like and trilling. Oanh translated line by line:

If you love me come back to this beautiful province with me

I stand on guard at this bridge, for seven years strong here Through cold and rain

I stand looking at the yellow star flying in the flashing light

And each call that I hear from the South tears into my heart.

Behavior change is hard, yet events, as Oanh once said, can remold your spirit. That song combined inside me with what Vietnam’s president Ho Chi Minh had called the spirit of resistance. I told myself if Oanh and his compatriots could make a life amid such devastation, I could re-make myself. I would act more like my heroes: Madame Binh, Che Guevara, the Trung sisters, and Emma Goldman. I would become less self-centered. I would sacrifice my happiness for the good of others. I’d learn empathy, compassion, determination, and resistance. The promises I made to myself in that factory cave in 1970 feel pretentious to me now but at the time they felt genuine. I would change my understanding of myself, and thus my life.

It’s Thursday, January 24, 2013, our second day in Hanoi. Having overdressed the day before, I had underdressed this day. I’m freezing. I ask our guide Minh, a smiley rotund man who I’ve just met, if our group could stop at the hotel so I can grab an extra layer, but there’s no time. Minh offers me his jacket with that same warmness of heart and desire to help that I remember as characteristic of the Vietnamese I met 40 years previously. I decline. It would be too great a sacrifice for Minh and too oversized (and grungy) a garment for me. I remind myself that since Vietnamese guerillas fought under conditions incomparably worse than mine, the least I can do is get through a chilly day.

Our bus has no holes in its floor; rather, it is equipped with upholstered dark blue seats, wide windows and an up-to-date microphone and speaker system. The traffic has also updated itself; the waves of bicycles that I encountered in 1970, carrying women in black trousers, white blouses, and conical straw hats, and men in white short-sleeved shirts, have morphed into honking, seemingly unstoppable motor scooters.

During the war, this factory had produced uniforms for the North Vietnamese Army. Today’s Garco 10 Corporation manufactures shirts, tailored suits, trousers, and jackets for men, women, and children. For companies such as Pierre Cardin, J.C. Penney, Perry Ellis, Liz Claiborne, Tommy Hilfiger, DKNY, and Target. Inside a low-slung building, women and men in sanitary white uniforms, cloth masks over their mouths, sit under florescent lights behind rows of high-tech white sewing machines. Bolts of cloth in dark violet and brilliant blue dominate the room like flowers in a field. Garco 10’s 11,000 workers can make wages of $200 a month; well above those made by most factory workers in modern Viet Nam.

Our delegation climbs three flights of stairs past a sign that promotes recycling.

Than Duc Viet, the director, has been delayed. We wait at a conference table in a large, windowed room furnished with a bust of Ho Chi Minh and chairs covered in pink slipcovers with the Garco 10 logo. Its three swooshes rising to a stylized peak remind me of the mountain under which the munitions factory lay. The COO tells us that his factory is designed with ecological principles to take advantage of the daylight and stay cool, and that employees can own shares of stock in Garco 10, which their children can inherit. He promises to show us the preschool the factory provides for workers’ children and workers’ on-site dental care.

Director Viet arrives; her eyes twinkle under black bangs. Introductions and an official program begin. Suddenly there’s a tap on my shoulder. I tiptoe to a room across a hall. It’s occupied by two women and a man. And a short pile of coats. A stream of Vietnamese consonants and diphthongs runs past me but I am mute, unable to comprehend the language. The older woman looks me up and down then, with no hesitation, selects one coat from among her stack of three. It’s deep Army green and made of soft polyester. The coat has black leather piping on collar and sleeves plus silver buttons with a heraldic crest. I do not question the woman’s choice. The coat is warm. And Judy Gumbo–style gorgeous; a revisionist version of what I imagine was once North Vietnamese army design. What better fashion to appeal to my revolutionary sensibilities? The man, clearly an accountant, hands me a slip of paper. I hand him $35 in U.S. currency. I walk back inside the meeting, no more a former antiwar activist with silver hair, but a 69-year-old model for the latest Garco 10 design. Director Viet embraces me, laughing with pride. I notice she has pinned on her yellow jacket a white and black button, the universal symbol for peace.

Director Viet tells us that she’s learning from her American partners how to take advantage of Viet Nam’s position as a player in the new, competitive marketplace. Americans, she says, know how to adapt to risk and come up with quick solutions. At the same time she expresses what, to me, is an un-American point of view. Her workers “are our parents to respect and our children to take care of.” In two years’ time she has met each worker personally. Whether or not they feel free to take advantage of it, all workers have her phone number. Three days after our tour of Garco 10, I stand beside antiwar activist and trip organizer John McAuliff as he introduces a delighted Viet and her COO to U.S. Ambassador David Shear.

Ho Chi Minh famously said, “nothing is more precious than independence and freedom.” To me, the Garco 10 factory feels like a twenty-first century Vietnamese version of Pete Seeger’s “Talking Union”: “shorter hours, better working conditions, vacations with pay, take your kids to the seashore.” At the same time, I realize that to navigate the worldwide capitalist free market, companies such as Garco 10 must make a profit or go under. Before my 2013 trip I’d read that, in today’s post-war world dominated by the triumph of free market capitalism, the Vietnamese government is promulgating what they call a “socialist-oriented market economy.” The day after the factory visit, I have an opportunity to ask an official, a charming man with an ironic sense of humor who is the Deputy Director of the government’s Americas Department, what the phrase actually means. He responds in what diplomats label an “open and frank” manner. I pick up that the Vietnamese want to transition to a new economy that will combine socialist values with capital markets while avoiding the systemic economic collapse of the former Soviet Union. The Minister emphasizes process. “We have to go slow,” he says, “because we must make sure not to fall down.”

Creating a socialist-oriented market economy in Viet Nam in 2013 may not be the outcome I anticipated in 1970, but I fought against the war so Viet Nam could gain its independence. The future is up to them.

1970: Remnants of War

All the photos I took in Viet Nam in 1970 are black and white, yet the vivid greens and earth tones of my memory are closer to my actual experience. In Thanh Hoa province, I took one photo of eight women lined up in formation, four abreast. Each wore a pith helmet and those ubiquitous black silk pants. They were a platoon of artillery gunners. They appeared as short as I was and, like me, looked in their mid-20s. One woman was barefoot; the others wore black sandals recycled from used rubber tires. Behind them, a six-foot-tall anti-aircraft gun stood erect, mounted on what looked like a tractor spattered with mud.

I can picture myself now in my pink-and-blue tie-dye tank top, hair braided to ward off the heat, climbing into the metal swivel seat of that Russian anti-aircraft gun and staring out through its elongated sights into a blue Vietnamese sky. Jane Fonda had her picture taken in this same model gun when she visited North Vietnam two years after I did, an act Jane says she now regrets. Jane’s enemies used the photo to brand her a traitor. Her friends tell me that photo made the task of winning mainstream Americans to the antiwar cause more difficult. I have never regretted my choice to sit in such a weapon, but I do remember feeling like a fraud. My life was one of privilege. How could I compare myself to women for whom making it through one day meant aiming a gun mounted on a tractor at airplanes out of whose bellies fell canisters filled with shrapnel, white phosphorous, or napalm jelly engineered to stick to clothes and skin? Chi, our female guide, introduced Nancy, Genie, and me to the brigade of women soldiers saying, “These are American friends, come to observe what we do to liberate our country.”

“You are an inspiration to me.” I replied. Chi translated.

“No, no,” a barefoot soldier said. “You, dear friends, inspire us. You help us end war in your country.”

The barefoot soldier handed me a grey-green metal ball as if it were detritus of little value. It was round and hollow; two and a quarter inches wide, three-quarters of an inch deep with a jagged hole in its side as if a single tear had burned acid-like through its metal casing. It looked like a baby pomegranate cut in half; except instead of seeds its skin contained ball bearings; testament to the lethal promise of a weapon designed to shred the flesh of any human being or animal unfortunate enough to be in range. In a mathematical progression of expanding death, each of these bombs, known as pellet bombs or “pineapples,” contained 250 steel pellets. From 1964 to 1971 the U.S. military ordered at least 37 million such pineapples. Pineapples like mine would be housed inside “mother” bombs dropped by B-52 Stratofortress bombers. A single B-52 could drop 1,000 pineapples over a 400-square-yard area. Between 1965 and 1973, the U.S. Strategic Air Command launched at least 126,600 sorties of B-52 bombers.

In addition to the POW letters I brought with me when I left Viet Nam in 1970, I also brought my bomblet. I use it to this day to illustrate the inhumanity of war.

2013: Remnants of War

I did not understand before my 2013 visit the unprecedented level to which the war had polluted Viet Nam’s countryside with toxic waste. A sign at the Mine Action Center in Quang Tri Province reads: “Welcome to Quang Tri, American Peace Activists on 40th Anniversary of Paris Agreement.” It’s there I encounter displays of unexploded pellet bombs. Not just a single one like mine, but hundreds. The tools available for clean-up are handheld hoes and metal detectors. Supplemented by bright red signs warning Danger! with a graphic of a skull mounted on two crossed bones. Quang Tri’s capital district was carpeted by 3,000 bombs per square kilometer. Pellet bombs remain buried in the soil out of which they rise, unbidden and undead, to maim and kill children who mistake the orbs for playthings.

At Quang Tri’s Cemetery of Fallen Combatants I wander past tombstones, steles, red pagodas, engraved with names or lists of names; row on row of white stone each bearing a gold star emblazoned on a red circle. The words of a World War I Canadian poem I had memorized in grade school intrudes: We are the Dead. Short days ago we lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, loved and were loved but now we lie in Flander’s fields.2 On the bus I notice we pass the occasional one-room three-sided box, a painted dollhouse perched on a concrete pole in squares of green rice paddy. These turn out to be traditional Vietnamese grave markers, scattered like multicolored psychedelic mushrooms in the fields. I’m a widow now. I’ve been best friends with inconsolable grief; still I am surprised by the intensity of remembered sorrow and pain that rises in me from the uncountable numbers of graves I see in Quang Tri province.

We arrive at the former U.S. airbase at Da Nang. Here is where American GIs offloaded barrels of the toxic herbicide Agent Orange. We’re told the Da Nang airbase is the most contaminated area in the world. Today a creek flows between green grasses, next to what look, from a distance, like abandoned, brown apartments. At first the creek looks innocent enough, but then I start to feel my mouth burn. Could this be real? I ask myself, or merely psychological, an empathetic reaction? A guide gives us a simple formula: dioxin is a byproduct of Agent Orange. Dioxin adheres to soil. Contaminated soil in ponds and streams gets incorporated into ducks and grass. The consequences to human health are not so simple: lung cancer, diabetes, lymphoma, leukemia, kidney disease, and mental disorders. I am shown a photo of a recent visit by a delegation of Americans and Vietnamese. They hold a banner that reads, “Even today, U.S. Veterans and Vietnamese People are Dying from Agent Orange.”

Da Nang is just one “hot spot,” and I’m told of others: Bien Hua and Phu Cat. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has committed funds to clean up just this one. The plan: 100,000 cubic meters of earth at the former U. S. airbase will be dug down 10 feet, then put inside a mountain of concrete boxes that look like a stack of gigantic evil Legos. The contaminated earth will be heated to 300 then 700 degrees. Such thermal heating is supposed to change the chemical nature of Agent Orange to render it nontoxic and usable for building roads. Walt, a stocky former Marine now a clean-up USAID technician with a beard, orange hard hat and wirerimmed glasses, warns me that I would not want to grow anything in such soil. Or breathe its fumes. Even after de-contamination. I look Walt in the eye, confess to being a former antiwar activist and ask what he thinks now about the war. “I’m a patriot. I used to despise you guys,” he tells me. “But what happened here is wrong.”

Our final stop in Da Nang is Friendship Village, a complex of white stucco classrooms. Warm sun shines through high windows, a blue banner hangs across the room’s front. Emblazoned on it in capital letters are these words:

WELCOME

AMERICAN FRIENDS/PEACE ACTIVISTS

TO DA NANG CENTER SUPPORTING FOR AGENT ORANGE

VICTIMS AND UNFORTUNATED CHILDREN.

Da Nang 31/01/2013

This trip has been fast paced, but now time slows. I hate the word victim, but in this case it feels apt. The center director, a man half my size, his legs bent and body contorted, tells our group that 1,400 intellectually disabled children live in the Da Nang area. I sit among them; girls and boys, faces and backs of heads flat, eyes slanted in that recognizable way, some with feet deformed and four toes, and one little girl, her body perfectly formed but at best only three feet tall. This girl appears ageless, with an expression under her straight brown hair and pixie face of such unbearable sadness it breaks my heart. The other children laugh and clap, but she will not join in or smile, as if she understands she has been cheated of a normal life by toxic chemicals leeched into and poisoning the soil of her community two generations before her birth. I believe, although I have no evidence of this, that this young girl knows whatever chance at normality her soul might have possessed had it been born into another body, has been cruelly taken from her by military decisions made in the United States and implemented at the Da Nang Air Base 40 years ago. I am unable to join in the raucous Gangnam-style imitation dance that the other children and my compatriots on the trip enjoy. The girl disappears, as if unable to tolerate the noise and celebration with its fun-loving intensity that disabled children can muster. I am responsible for the tragedy of this life, I tell myself as I leave. Yet I feel powerless to help.

1970: Celebration

I recall a story Oanh told our final night in Hanoi. It was June 6, 1970. Like his male colleagues, Oanh had dressed in grey pants, a white shirt and combed his black hair back 1950s style; Chi and the women from the Committee for Solidarity with the American People wore ao dai’s of faded reds and blues carefully preserved for special occasions. I knew the Vietnamese population suffered war-related food shortages, yet this banquet in our honor felt sumptuous; a traditional gesture of farewell and gratitude. Spring rolls fried a delicate brown, a green salad piled with bright red prawns, steaming bowls of Pho served concurrently with fish braised in brown sauce plus a beige vegetable unfamiliar to me, cut in fantastical shapes, gave off an alien scent. After a dessert of ripe yellow pineapple came slices of fruit with white flesh specked with tiny black seeds. The fruit was unfamiliar to me, as if an ironic Mother Nature had created a cluster bomb of peace and friendship just for us.

I’d learned by then that Oanh’s way was to teach through aphorism. His story on our last night was personal, unusual for him. It came from his own childhood, something his father had said to him when Oanh was a child, “You must not wait until the score is achieved to know who is the real hero.” Oanh said he did not have to wait until revolution would be achieved in America to know that Nancy, Genie, and I represented the future. He ended with this advice: “Be good to friends who are good to you; also be good to friends who are bad to you, for only friends will go with you on the long road to revolution.”

In 1970, I could not have asked for a more inspirational farewell.

2013: Celebration

It’s Friday, January 21, 2013, the 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Agreement. With a police escort to stop traffic and get us to the celebration on time, our bus whizzes past lines of cars and motorbikes driven by women in parkas, white masks over their faces to keep out pollution. We arrive. The bus door opens. To the rhythm of a military band, we walk up a red carpet past honor guards in white uniforms standing at attention. I wonder if our presence as American antiwar activists could be more significant than I thought. What looks like 800 guests are gathered inside a vast auditorium. Ten older men, grey haired, balding, dressed in white uniforms, plus one woman in green military garb sit near me in a row of red plush seats. All display on their chests a cornucopia of medals, ribbons, and red stars. I seize the opportunity and make my way down the row, an impromptu ambassador from Woodstock Nation, shaking each of their hands as I say, in English, “Thank you.” They beam with delight.

Madame Nguyen Thi Binh and diplomat Luu Van Loi are escorted up to an oversized stage. The two stand in front of red curtains on which a gold star and hammer and sickle hang, behind a gold bust of Ho Chi Minh at least three times their size. As a red diaper baby, I understand such symbols must accompany any official occasion celebrated by a communist government. Madame Binh and Luu Van Loi are given the Heroic Award of Armed Forces—the equivalent of a “lifetime achievement award.” At 86, Madame Binh is now the only living signer of the Paris Peace Accords. She had been my ideal romantic hero since the late 1960s; a foreign minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Viet Nam, and a leader of the Viet Nam Women’s Union. She had headed the PRG delegation at the Paris Peace Accords.

Onscreen, an arc of Vietnamese resistance unfolds as Vietnamese orchestral music swells: young Ho Chi Minh with wispy beard fighting French colonizers; bombed-out buildings and pagodas with metal remnants of U.S. B-52s; bicycles and oxcarts guided by peasants in rubber tire sandals transporting goods down the Ho Chi Minh trail; Madame Binh signing her name to the Paris Peace Accords; destruction caused by two more years of carpet bombing; and finally tears of those who realize that what remains of their families, once torn apart by war, will soon be reunited. At the same time, women with fans and multi-colored ao dai’s of brilliant reds and yellows, and men in blue silk fill the stage in front of the screen in a pageant of traditional dances, accompanied by an ever-changing chorus of singers. The music slows. A line of young people enters, students, clearly non-Vietnamese. They’re dressed as hippies in jeans and multicolored shirts, and include a young man who plays an air guitar as if he is Bob Dylan. They burst into song: “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh,” written by our movement’s very own Red Star Singers. It’s a sublime public recognition of U.S. antiwar efforts.

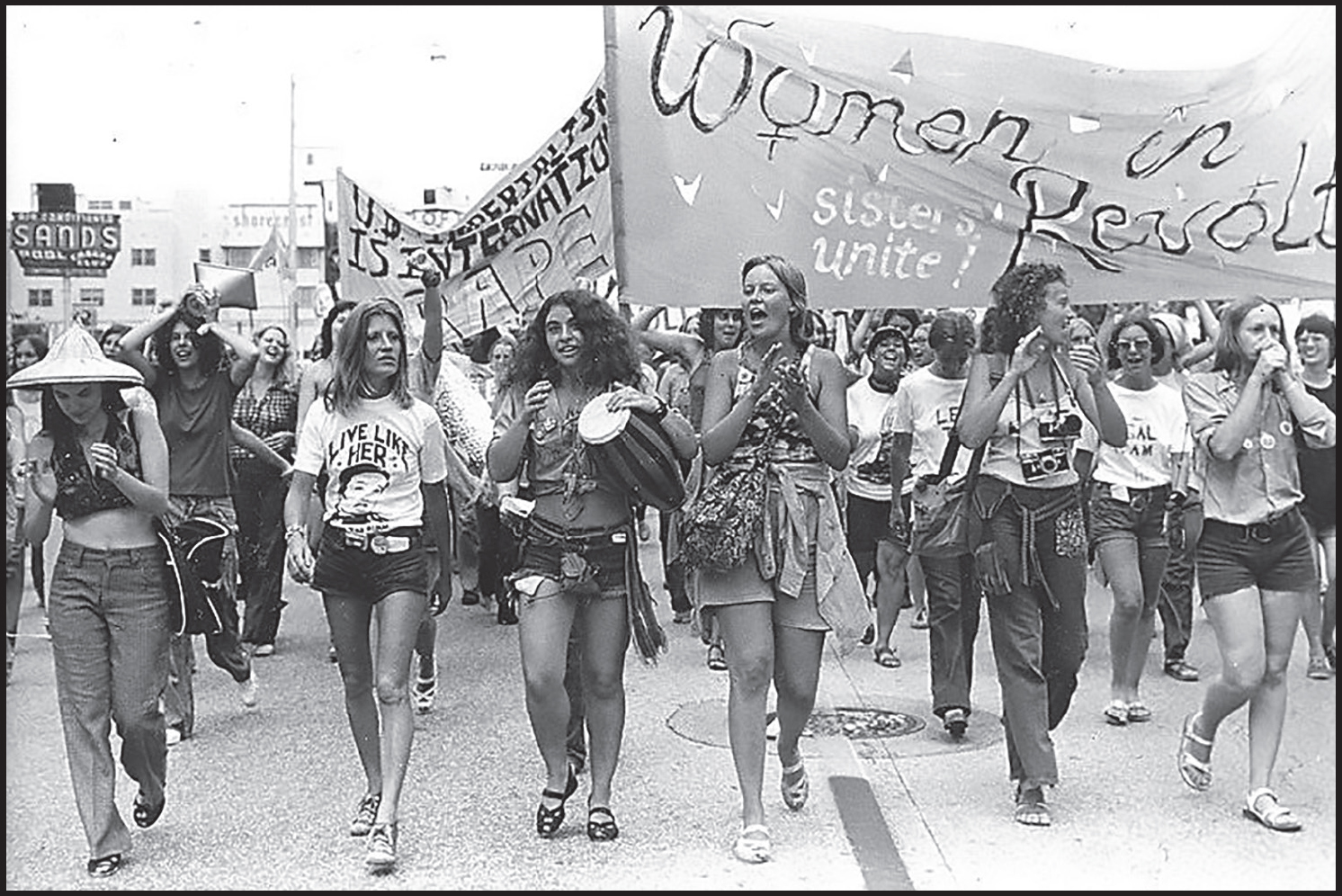

Judy Gumbo (with drum) at the women’s antiwar march, Republican National Convention, Miami 1972.

Photo by Jeanne Raisler, courtesy of Judy Gumbo.

Madame Binh enters the banquet hall. Her walk is steady, her hair still black and not yet grey, and her eyes shine behind her glasses. Even at age 69 my heart pounds in the presence of my hero. I approach her table, introduce myself, and hand her a black-and-white photograph I’ve brought with me from the United States. It’s of a 1972 women’s antiwar demonstration at the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach. “Women In Revolt, Sisters Unite!” our banner reads. The Judy Gumbo I remember marches in cutoff jean shorts at the center of the front line of demonstrators, pounding out a militant beat on a wooden drum I’ve slung over my shoulder. On my left in the photograph is a woman later identified as a police agent. On my right is Patty Oldenberg, who wears a “Mme. Binh Livelikker” t-shirt. I call it the “Livelikker” t-shirt because above a graphic of Madame Binh’s head, the word “Livelikker” appears; an unfortunate outcome of a volunteer designer squishing our women’s slogan “Live Like Her” into a single silkscreened word. Past meets present: I say to Madame Binh that I and my antiwar compatriots did our best to live like her. I tell her, “Thank you for what you have done.” As if in recognition of a common history and shared future, she replies, “And we will continue to do it,” then squeezes my hand.

When I left Viet Nam in 1970, I had fallen in love with the country and its people. Those were my exact words. When I left Viet Nam in 2013, I felt like I was saying farewell to a friend with whom I had not had enough time to share our intervening 40 years of pain and triumph. My trip in 1970 had been life-changing; my return in 2013 was life-affirming.