FROM HANOI TO SANTA BARBARA

BECCA WILSON

Part One: Hanoi, December 1970

Below are excerpts from an essay I wrote in 1971, in diary form, about the December 1970 People’s Peace Treaty trip to Vietnam. A longer version of this article was published on February 5, 1971 in El Gaucho, the University of California at Santa Barbara student newspaper, which I edited during the prior 1969–70 academic year.

December 2

The city of Hanoi is an ecologist’s dream. During our bus ride from the airport to the city, we passed through the “suburbs”: trees, vegetable gardens, small huts clustered among banana trees, weeping willows, and stands of bamboo. But even in the city itself, where most of the houses are two and three story French colonial style villas and mansions, there are hundreds of trees, parks everywhere, and several beautiful lakes. The city is vibrant, alive, but serene. People stroll down the streets or ride their bicycles. The only noise is an occasional blaring horn from one of the few cars as it as it warns the crowds to clear the way. [Young male] soldiers walk down the street holding hands; old women in black blouses and pantaloons squat in circles on the street corners, selling fruit and vegetables; children giggling and screaming run along the sidewalks in packs.

In our hotel today (named Hoa Binh, which means peace) we met with our guides and interpreters from the Committee for Solidarity with the American People. We gave Mr. Quat, the chairman of the Committee, a list of what we wanted to see and the people we wanted to meet and he assured us that every request would be granted.

As an introduction to our stay in Vietnam, Quat gave us an account of the history of Vietnam and the present political situation as it is seen by the DRV (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, what we call North Vietnam). Quat began by explaining that the Vietnamese see their history as a long struggle against foreign invasions and for national independence. The Vietnamese people’s first victory came in the thirteenth century over invaders from Mongolia. Next in line were the Japanese, then almost a century of French colonialism. This history of struggle against foreign domination, we soon learned, is in the blood of every Vietnamese. It is passed on from generation to generation.

Quat’s own personal life is testimony to this national consciousness: now in his late 40s, Quat moved to the North in 1954 when, in accordance with the Geneva Agreements, all forces resisting the French agreed to relocate north of the 17th parallel. National elections, promised in 1956 to reunify the country after the temporary division, were never held, and Quat has not seen his family for 16 years. Just recently he received word that his wife’s two brothers, having heard about the renewed bombing of the North, joined the NLF.

December 7

Our bus journey to Linh Binh province today was long…. We had to pass over several makeshift one-lane floating bridges built by villagers to replace steel bridges destroyed during the four-year air war, from 1964 to 1968. The original structures will not be rebuilt, I suppose, until the people are reasonably sure that there will be no more bombing.

On the way to Linh Binh province we passed a large field, torn up and full of rubble. One of our interpreters explained that this was where the village of Phu Ly had once been. During the air war, every hut in the village had been destroyed by bombs, and many of the villagers had been killed. Occasionally, in other villages that we passed in our bus, we saw crumbling remains of homes and buildings along the road; we could see individual manhole-type bomb shelters, bunkers, and trenches. But generally, despite these sights, we found that we had to remind ourselves that we were visiting a nation in a state of war. There really is an uncanny serenity about this land—no cars on the road, and no one is in a hurry. Young women and soldiers ride along calmly in the rain on their bicycles; children squatting under trees wave and point as we drive by; little boys sitting on a water buffalo watch their elder siblings plow; families wade in the rice paddies, building irrigation canals out of chunks of mud or harvesting the last of the season’s rice crop.

The slogan most popular in Linh Binh is “The Song Can Overcome the Bomb,” the province chief told us with a giggle. Before inviting us to lunch, the chief, a small, sturdy, intense man of about 55, talked about the effects of the four years of bombing on Linh Binh province. The 500,000 people in the province are mostly peasants, he said, and 10 percent are Catholics. During the “air war of destruction,” as the Vietnamese call the four years of U.S. bombing, over 10,000 tons of bombs were dropped on the province. Out of a total of 123 villages, 113 were attacked. Several townships were completely razed.

“They claim the targets are military, but without exception they strike at the people—at hospitals, schools, dikes, markets, churches, pagodas,” the province chief calmly declared. “They even attacked our cemeteries. Even the dead cannot have peace.” He gave us many concrete examples of churches being bombed, of schools being attacked as classes were going on, of open-air markets being bombed in broad daylight.

Large crowds of people of all ages gathered around us as we surveyed the ruins of three churches that had been bombed in 1968. At the first two churches only the walls were still standing. Bomb craters, some as large as 100 feet in diameter, now filled with water, circled the ruins.

The villagers, who had been told we were Americans, smiled and waved at us; never did we see signs of hostility—only puzzlement and curiosity. We witnessed bitterness only once, when we spoke to a 75-year-old nun who had been one of the few survivors of a bombing raid that demolished several buildings in the church compound including part of a chapel and the entire nuns’ dormitory. Twenty-eight people, including five nuns, 11 children, and five pregnant women, were killed; 31 persons, including 15 children, were wounded.

The old nun said that the attack came suddenly at 11:30 one morning; without any warning, the planes came flying low and dropped eight bombs. All she remembers is a thunderous explosion. While she was talking she stared past us, unable to look at us in the eye. A younger nun came in the room while the old nun was talking; she didn’t want to talk about the bombing, saying that her mind “wasn’t too good” ever since she was injured in the bombing. But she nodded approval when the older nun asked us to go back to the United States and demand that President Nixon send reparations for the damage done to the church. “As Christians, we will do all we can to fight against the United States imperialists, but we want reparations,” she said right before we were about to leave.

I’m still haunted by the despair in the nuns’ faces. All of us were deeply affected by the experience. We couldn’t talk too much for a while. We were tense and sullen on the bus ride back to Hanoi, but our mood was transformed when we got out of the bus to wait while a flat tire was being changed. Our presence immediately drew the attention of bicycle riders, passers-by, villagers, and people working in the nearby fields. Within about 10 minutes, we were surrounded by a crowd of about 100 people. They asked the interpreter who we were, and he said we were American students. Immediately, smiles lit up on all the faces.

Some of the people walked up and warmly shook our hands. Then they sang us a song, the song of unity. We sang them “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?” They watched us with affection and excitement in their eyes, and applauded wildly when we finished singing. A young man in his 20s leaned over on his bicycle and said earnestly, “I hope that when you go back to America, you will tell the American people the reality of Vietnam and the destruction caused by the United States imperialists. I am sure that if the American people know the truth, they will try to end this war.” We promised him that we would do as he’d asked.

December 8

They teach their children not to hate American people. The children know the difference between the American people and the American government. Their mothers and fathers and schoolteachers call those who come to bomb and maim “U.S. aggressors” or “U.S. imperialists.” Rarely do they call them “the Americans.”

It’s difficult to understand how and why the Vietnamese are capable of making this distinction. But apparently, it’s an integral part of their culture and history. Tri, one of our guide-interpreters, a small, gentle middle-aged man who often laughs wryly and wistfully as he talks, gave me an example today: when the Vietnamese defeated the Mongolian invaders back in the thirteenth century, they built them a whole fleet of ships, loaded them up with food and provisions, and sent the remaining Mongolian soldiers off to their homeland.

We met some children today while we visited Hoa Xa collective farm, about two hours by bus from Hanoi. As we walked by the farm’s kindergarten class, the children were singing a song. We stopped to watch them and asked the interpreters to translate the lyrics. It was a song the children sing to help them to learn how to count: the child asks his mother, “Mommy, mommy, how many bombers do you see in the sky—one-two-three-four-five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten?” “Dear child,” the mother interrupts, “there are too many bombers for me to count.”

December 10

I’ve often had the feeling, since we’ve been in Vietnam, that I’m watching a play whose characters are larger than life. Today was different. We weren’t just visitors, observers, but we became participants and we shared a day in the life of a group of Vietnamese people.

Our visit to the campus of one of North Vietnam’s two agricultural universities started with the kind of meeting we had become accustomed to: the school’s director proudly discussing the institution’s achievements, the determination of the students to keep studying “under the rain of bombs,” their brave attempts to protect from United States aircraft the buildings they had built with their own hands....

As with other meetings we had had with the Vietnamese, we learned a lot, but felt like outsiders. Our lives touched our hosts’—and vice-versa—only in the abstract. But a few minutes after the meeting, it all changed. A group of students took our arms and ushered us into the school’s combination cafeteria-meeting room-dining room. We sat among the school’s entire student body, who had gathered to sing songs for us and with us. They sang us a few songs, joyous and hopeful in tone. We sang them the only two songs all of us knew (“If Had a Hammer” and “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”). Then, together we all sang the Vietnamese song of unity. And you could really feel unity in the air.

Most of the students went back to their classes, but a group of them stayed to show us around the campus. Clusters of one-story mud and clay buildings with thatched roofs, surrounded by fields in various stages of cultivation, serve as classrooms, dormitories, and labs. Walking around we also noticed several lakes, but were informed that some of the bodies of water we were seeing were not lakes but bomb craters now filled with rain water. The students walking with me, their arms in mine, said that before the bombings, they used to swim in the lakes; but today they are filled with unexploded bombs and mines, making swimming too dangerous.

At lunch in the school cafeteria, we ate the delicious, fresh, non-chemical food that the students produce themselves, and exchanged talk about our schools and hometowns. During dessert, the students disappeared somewhere. A few minutes later, we saw the whole student body marching in the campus’s main quad, single file, carrying banners and red flags with bright gold stars (the flag of the DRV). Some of them—even the women—wore helmets and leafy camouflage and carried rifles.

What we were witnessing was a demonstration organized that day in every school of North Vietnam to protest the shooting, a few days before, of a 12-year-old South Vietnamese high school student by an American G.I. As the students marched in the quad, heads held high, faces serious and intense, they alternated curt chants with raised fists. We were invited to join in. We stood in the rain with them, wearing conical straw hats like theirs. Two students gave passionate speeches about the feelings of solidarity between the people of the North and the South on their common struggle for independence and freedom. Two of us spoke, about our feelings of solidarity with them, about our promise to try to end the war when we got back home. When David Ifshin got up and burned his draft card, the students applauded wildly; some of them had tears in their eyes.

The demonstration was over within a few minutes. Just as serious and disciplined as when they earlier filed into the quad, the students marched away, back to their afternoon’s activities. One group’s task was to build an outdoor stage for plays and other cultural activities, and the American delegation was invited to help out. Armed with shovels and spades, our job was to cut up the moist, compact earth into cubic chunks, put them into straw baskets hanging from a bamboo pole to be swung over the shoulders and carried to another part of the field. It wasn’t easy.

Even those of us who had done manual labor before (including the 6’2” men) found it difficult. Our interpreters, city dwellers who never work in the fields and most of whom are under 5’3”, made us look like oafs. We discovered that carrying the baskets full of earth not only takes strength, but also grace and coordination.

The contrast between the big, muscular Americans and the frail, small Vietnamese at work made everyone hysterical with laughter. We were sweaty within 10 minutes and stumbled all over the place while carrying the baskets. After 20 minutes, the Vietnamese became concerned about our health and made us stop working. To refresh us, they had especially brought to the field a large thermos of green tea. They toasted us for our efforts as most of us were still laughing at our own ineptness.

The symbolic nature of sharing manual work moved us all. But, to the Americans, the contrast between us and the Vietnamese—our brute strength, their skillfulness and grace—was also chilling. It seemed a perfect metaphoric vignette of the war: the United States’s inability to win, despite tremendous technological and military superiority.

Another vignette later on in the day was a basketball game that some of the men in our delegation played with a group of Vietnamese students. Those of us who watched couldn’t help but see the same arrogance and aggressiveness in the American team as we have associated with brash military men. The American team, from the start, was really trying to win, their faces anxious, their movements rough. It began as just an enjoyable game, but soon the competitiveness of the Americans rubbed off on the Vietnamese team, and then both sides were bent on winning. The game ended up a tie, fortunately.

The Vietnamese relied on swift maneuvers and finesse in their movements. Our side took advantage of being taller and stronger to make points. The audience, I’m sure, wasn’t especially aware of this particular symbolic aspect of the game. They clapped just as enthusiastically for both teams. But the players—even if unconsciously—were. Both teams sat down together after the game for a drink. And for the first time in Vietnam the atmosphere was unmistakably tense.

Those of us on our delegation who’d been watching the game saw in ourselves—young Americans who like to think we are part of a new culture—the same offensive, aggressive qualities that make Americans disliked all over the world. Perhaps we were exaggerating the game’s symbolic value—out of our guilt, our inability to accept love and praise from the people our country is killing and maiming. Perhaps we saw more in the game than was really there. In any case, one reality that all of us have been aware of throughout our experience in Vietnam is that if we young Americans want to build a new world, we’ve got a lot to recognize and overcome in ourselves. It wouldn’t hurt us to be “Vietnamized” a little.

December 12

We had our second meeting with the National Students’ Union today. By the time of our first meeting with the students on our fifth day here, we had already discovered that there would be nothing for us to “negotiate” with them before signing the peace treaty. Like the Vietnamese students, it is obvious to us that the United States must immediately and completely withdraw from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The rest is up to the Vietnamese to solve and decide. But all of us on the delegation strongly support the eight-point peace proposal of the Provisional Revolutionary Government.

The Vietnamese students asked us about plans of the antiwar movement in the United States. We explained that the movement has been silenced, that people are intimidated, frustrated. (The North is being bombed again, but where is the protest?) We also told them about plans to revive the movement around May 1. Major antiwar groups behind the idea of “people-to-people peace” are calling May 1 the “people’s deadline to end the war.” If by that time Nixon has not announced his intention to withdraw all troops, massive protests will take place nationwide.

Thereafter, besides massive demonstrations and non-violent civil disobedience, an intensive educational campaign will attempt to inform the American people about the Vietnamese proposals for peace and try to awaken them to Nixon’s real intentions of continuing the war with a smaller number of troops, but a larger number of bombers. The students were heartened by our words. They thanked us, as they had before, for “waging such a courageous struggle.”

Quat, our host from the Solidarity Committee, was also at the meeting. He tried to explain the depth of feeling that the North Vietnamese have for their compatriots fighting in the South: “No words can express our sentiments,” he began in a quivering voice, “We feel very strongly, from the bottom of our hearts, when we hear of massacres against our people in the South. It’s not just a political feeling, it’s deeply personal, because no one in the North does not have some relations in the South.”

“Some people think that all students in the North are communists and that those in the South are nationalists—as a matter of fact, not all the students sitting here today are communist. It’s not a question of communism or non-communism. The reality is that we all face the calamity of United States aggression.”

December 13

Our hosts really don’t want us to suffer too much. They are always sure to schedule intense meetings preceded or followed by relaxation or entertainment. Today they prefaced the meeting we had requested with the Committee for Investigation of United States War Crimes with a morning of rowing in one of Hanoi’s beautiful lakes. I guess they knew it was going to be a heavy experience for us.

We were given a documented discussion of the kinds of weapons used by the United States in Vietnam: the dozens of different kinds of “anti-personnel” bombs designed to kill and maim people dropped daily for four years in the North, and now dropped daily in unimaginable quantities in the South; the pacification program, which drives people out of their villages with defoliants, explosive and anti-personnel bombs and into “strategic hamlets,” or refugee/concentration camps where they can be controlled and isolated from the NLF. The statistics and details are so staggering that they lose their meaning after a while. We were literally numbed at the end of the presentation.

We were then introduced to three people who had been victims of the weapons we had heard about. (This was also at our request: We wanted to be sure to get at least one visceral glimpse at the war’s horrors.) First we met Phan Thi Thiem, a woman age 22, wounded on March 28, 1970, by a pellet bomb. Such bombs explode into fragments so tiny that they can’t be removed. She and her co-workers in the state store in Nghe An heard the planes coming and ran to a shelter. One bomb fell right on the shelter, wounding her two friends. One died a few minutes later. Another pellet bomb exploded above the shelter, piercing Thiem in the neck, shoulders, arms, and thighs. All of the pellets are still in her body. She took off her blouse to show us the pellets. Just that movement was excruciatingly painful. So is walking outside on a windy day. Or taking a bath.

The second victim we met was Nguyen Duy Luy, age 25. We could hardly look at him. He had been disfigured by a phosphorous bomb on Sept 21, 1969, while he and his team were working on their rural cooperative’s land. Today, after six plastic surgery operations, he still looks almost ghoulish. The planes had come and dropped two phosphorous bombs as they passed over his field. Luy’s three co-workers died on the spot. All he remembers is seeing a big fire. Then the fire ate him up.

Bui Van Vatt, age 20, was the third victim. He looked normal except for bandaged hands and a five-inch long scar around the front of his neck. He had been wounded (unlike the two others) in the South on March 14, 1970. Artillery was being fired into his village; he ran to a bomb shelter. Two planes flying very low spotted him and released a phosphorous rocket. His hands and chest were hit. He was given first aid at the village, then four people started transporting him to the hospital. On the way there they met 12 American G.I.s, who killed the people transporting Vat with machine guns, then cut off their heads with knives. The G.I.s weren’t sure whether Vat was dead or not, so they kicked him a few times; he pretended to be dead. They kicked him again and then slit his throat.

Colonel Ha Van Lau, the chairman of the Committee, stood up after Vat left the room and said, “The G.I.s are directly committing these crimes, but the real criminals are the United States imperialists who make those boys into murderers. We always remember what the mother of Meadlo, one of the G.I.s in the My Lai massacre, said to Nixon, ‘I have given you a pure boy. You have given me back a murderer.’ We are sure that when the American people know the truth, they will want to stop this war.”

We wondered: Hadn’t most Americans heard about such atrocities? Are we all a nation of Good Germans?

This morning was our second session with the War Crimes Committee [Committee for Investigation of United States War Crimes]. And [it was] just as horrifying as the first. Two doctors, specialists in chemical warfare who devote all of their time researching the effects of toxic chemicals used in Vietnam by the United States, spent two hours with charts, formulas, and photographs scientifically proving to us that one of the defoliants used in Vietnam causes genetic abnormalities.

One of the deadliest of the chemicals is a defoliant called 2-4-5-T. It is considered an agent of biocide, in that it has the capacity to kill everything that is living—plants, animals, and human beings. According to testimony by Jackie Verret to the 91st session of Congress, the doctors said more than 40 million pounds of 2-4-5-T were sprayed over a period of nine years over an area of 5 million acres in South Vietnam.

Then we met three young mothers who, while pregnant, had lived in areas where 2-4-5-T is used. They carried their deformed babies in their arms. One of the babies, a year old, has a shrunken head about the size of a grapefruit. Doctors say he “almost has no brain.” He can’t hold his head up, has no muscle coordination, and cries constantly. The other two children, ages 2 and 3, look bizarre but not deformed. They can’t walk, sit, or stand, are mentally retarded and have chromosomal abnormalities.

We had been furiously taking notes; outside we snapped a few pictures. Afterwards, we apologized to the mothers for submitting them to such cold, clinical treatment. One of them answered that she didn’t mind, since the information would go back to the American people. “I’ll do anything to prevent this from happening to another person.”

During the first week, we had been caught up in a kind of euphoria, being treated with such touching warmth by everyone. The horror of this war hadn’t really struck us until yesterday. We began, too, realizing the strength it takes the Vietnamese to be able to sing and laugh amidst this atrocity. We began to understand what self-control it takes for a group of people whose families and friends have just been bombed by the plane they just shot down to be able to take the pilot away to a prison camp without laying a hand on him.

December 15

We’re now in Ha Long Bay, staying at a resort hotel deserted most of the time except when foreign visitors are taken here. Nixon’s press conference announcing his intention to renew bombing of the North if any more reconnaissance planes are shot down took place only five days ago. But the people, even in this beautiful seaside resort area, are getting ready. On the way here in the streets of Hanoi, we noticed that the people have started cleaning out the man-hole type shelters along the streets; the first few days we were here, they had been full of garbage and dirt. We crossed Haiphong Harbor on a ferry on the last stretch of our trip to Ha Long Bay. Aside from gigantic Russian and Chinese tankers looming over the water, we saw dozens of small, hand-built boats with sails that resemble fans—the same kinds of boats the Vietnamese used to fight against the Mongolians. Today they don’t do much good against the United States, but at least they help the people to stay alive; they’re fishing boats.

The countryside after we left Haiphong resembles the coast of California. In the woods and forests and fields we drove through along the seaside, we saw groups of people about our age squatting in circles, climbing up hills, marching in line. Oahn, one of the interpreters, said that the people were in military training. We weren’t too surprised, until we kept passing throngs and throngs of people—we must have seen 2,000 to 3,000 people, all under 30 and half of them women, in maneuvers. When we got to Ha Long Bay, the province chief informed us that after the call of the Workers’ Party for the people to renew their preparedness (in response to Nixon’s threats), 10,000 young people in the province had volunteered to join the militias or the army.

Aside from the doctor who accompanies us every time we go to the provinces, this time we have each been given a metal helmet to bring along for protection. Some of our interpreters wear pistols on their hips. We never really thought we’d be needing the helmets, but we were wrong. Just a few minutes after we’d gone up to our rooms for our naps, a 16-year-old girl carrying a machine gun excitedly pointed at our helmets on the chair and gestured for us to go downstairs. We ran down the stairs and were told to stand under a doorway. Trembling, we asked what was going on. It was an air raid—radar had picked up a group of U.S. planes from the 7th fleet coming in our direction.

The machine-gun toting girl and the other young girls who work at the hotel scurried up on the roof, ready to shoot. By this time our group was nearly in a panic. The Vietnamese, of course, were as calm as always. They said we’d have to wait five minutes to find out if we’d have to go to the shelters. It was a hell of a long five minutes. We had already accepted our (at least honorable) deaths by the time the hotel manager ran up to say everything was alright—the planes turned out to be reconnaissance planes, flying 60 kilometers away from here.

Aside from that scare, the stay here has been rest and relaxation all the way. At least for us, it has. But for many people in this province, it’s time to prepare for escalation of the war. Even after dinner, as a group of students and workers sang us songs, we could hear military chants in the distance.

December 17

We signed the treaty today. And this morning had our last meeting with the North Vietnam National Union of Students; we were joined by representatives of the Liberation Students’ Union of the NLF, who had heard about the treaty while visiting Hanoi and wanted to sign it. Toward the end of the meeting, Nguyen Thi Chau,1 a member of the central committee of the Liberation Students’ Union, got up to sing us a song.

Chau cried tonight, as she signed the treaty with us under the blinding lights of movie cameras. She started to talk about the deep feelings she had for her comrades in the North, but couldn’t finish. Tears streamed down her drawn face. When it came time for Hien (the North Vietnamese students’ representative) to say a few words, he too, was crying—and too moved to speak.

We were more affected by that silent communication than we ever could have been by the symbolic act of signing a peace treaty with our supposed enemies. Our presence was irrelevant to this passionate expression.

Our country had created the pain we were seeing. Our country had perpetuated the artificial division of Vietnam, the separation of families from families, of friends from friends. Our country had invaded their country, devastated its countryside, killed and maimed its people, created the birth of monstrously deformed children.

We had just signed a piece of paper that, in effect, had disassociated us from what our country had done. But our hearts were not full. Right as we stood there watching the pain and suffering of two Vietnamese people, one from the North, the other from the South, the war went on only a few hundred miles away, on the same soil we were standing on.

Leaving this land and these people would not be truly sad; what would be sad would be for us to come back to the United States without feeling a human duty to fight to stop the horror and pain. It would be sad if we left remembering the pain without the songs, the songs without the pain.

December 19

On our way home, I wasn’t really sad to leave. It was like saying goodbye to your parents before going off to war, trying to show you’re strong and not afraid, knowing you may never see them again.… I’ll never forget what Premier Pham Van Dong told me yesterday as we said goodbye after a warm encounter. He picked each one of us a rose from his garden, and each of us shook his hand and said goodbye. I told him that I hoped we’d meet again on the day of the common victory of the American and Vietnamese people. Fatherly, serious and tender, he said the struggle would be long and hard but added, “You will need courage, courage, courage. The rest will come by itself.”

Part Two: Santa Barbara, 1971

January

Santa Barbara, California, my hometown at the time, took up the People’s Peace Treaty more swiftly and enthusiastically than I’d anticipated. In January 1971, soon after I returned from Vietnam, I and a small group of friends launched an organizing campaign around the Treaty. Most of our early success grew out of the outspoken support we received from Tom Tosdal, newly elected student body president of my alma mater, University of California–Santa Barbara (UCSB). Tom had not been active in the loose New Left coalition on campus that I identified with, which had spearheaded antiwar and student power protests and allied with black and Chicano activists. In fact, because Tom had defeated a candidate more closely tied with these movements, I was surprised and immensely grateful when he became the Treaty’s main champion on campus. After Tom asked his student government colleagues to support the Treaty, the student council not only enthusiastically endorsed it, they decided to turn it into a referendum to be placed on the next student elections ballot. It was ratified by an overwhelming majority.

February and March

In early February, four friends and I crammed into a car for a marathon round-the-clock road trip to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to attend the national People’s Peace Treaty conference, aka the Student and Youth Conference on a People’s Peace. At this exciting gathering, which attracted nearly 3,000 activists from all over the country, we devised plans for an educational campaign based on the People’s Peace Treaty, and for a series of May Day demonstrations, primarily in D.C., but also in major cities and college towns nationwide. Nixon had just invaded Laos a few days before the conference began, and because of our large numbers, attendees at first had been tempted to stage an instant demo. Instead, we decided nearly unanimously that it made more sense to spend our precious moments together getting down to work. The organizing slogan for the conference, which Rennie Davis was instrumental in coordinating, was “Peace Is Coming—Because The People Are Making The Peace.” We explored ways to reach out to activists from the veterans, labor, and Black, Chicano, and women’s liberation movements. And because the conference agreed to endorse the No Business as Usual (aka “Ghandi With a Fist”) tactic, we also learned the basics of civil disobedience. As one of my friends later wrote in the UCSB student newspaper soon after the conference, “Other actions will take place across the nation, which whenever possible, will follow the model of disruptive but non-violent tactics.... Marches have been ineffective. On the other hand, there are many people who do not approve of street fighting and yet are sincerely opposed to the war. Civil disobedience can involve large numbers of people and at the same time force the government to respond.”2

Over the next couple of months, I and my friends (mostly students and recent ex-students) forged an alliance with the newly formed local chapter of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) and began working together to bring the Treaty to the older generation activists, traditional peace groups, pacifists, and progressive ministers in town.

Our UCSB-based student peace and anti-draft movement had primarily focused on exposing the university’s complicity with the war, opposing ROTC, and challenging the right of Dow chemical and other corporations profiting from the war to recruit on campus. We’d rarely done this kind of local community outreach, primarily because just as antiwar sentiment was peaking, in late 1969 through early 1970, other campus issues took center stage and events began spinning out of control. (In early 1970, our campus experienced unprecedentedly large, peaceful but militant demonstrations protesting the firing of a young anthropology professor and countercultural icon. Several weeks of protest culminated in a massive sit-in blocking the doors of the administration building. In response, for the first time in campus history, administrators called in an army of outside police. Sheriffs from three counties descended on campus and clubbed several students, drawing blood—also a first. In Isla Vista, the student community [aka ghetto] adjacent to UCSB, the next four months brought a student shot and killed by police, three riots—two of which were police riots—the Bank of America burned to the ground, hundreds of arrests, and scores of injuries.)

Our group also brought the People’s Peace Treaty to the Isla Vista Community Council (IVCC), a new entity established in the wake of the bank burning. After polling local residents, who overwhelmingly backed it, the Council later endorsed the Treaty, and an IVCC rep became one of the most vocal leaders in efforts to get it ratified by Santa Barbara city and county officials. And within a month the IVCC unanimously passed a motion to erect ornate signs at all entrances to Isla Vista proclaiming, “This town is at peace with Vietnam.”

Among antiwar activists in my circle, the mood during this period was mixed. The Treaty did revive our movement’s morale, but battle fatigue and despair were still plaguing us. The following excerpt from an article published in March in the student paper captures some of the local zeitgeist. It was written by my friend Bob Langfelder, an early leader of the Santa Barbara chapter of the Resistance, the first nationwide draft resistance group, founded in 1966. In 1970, Bob was falsely accused and wrongly convicted of taking part in burning down the Isla Vista branch of the Bank of America. He lost his appeal and did a year in jail:

I just figured out it has been over 2,000 days since my first protest march against the war. 2,000 days of failure. 2,000 days of marching, picketing, vigiling, writing leaflets and letters, leafleting them, petitioning, reading, talking to all kinds of people; getting married, going into VISTA, getting un-married; turning in my draft card, refusing induction, counseling others to, waiting to be prosecuted, but after a year and [a] half, they make me 1Y; talking to more people and even rioting a little; being indicted, tried, convicted, sentenced to a year for inciting and participating in a riot that I didn’t really participate in.

It all adds up to failure. And it hurts even more now that it appears the Vietnamese could lose everything they have struggled for. I’m guilty of not doing as much as I could have for them. It’s like we who have opposed the war have won all the arguments, but we—or I—have found myself unable to repeat all the arguments like a daily tape recording.

As Noam Chomsky said, “Continued mass actions, patient explanation, principled resistance can be boring, depressing. But those who program the B-52 attacks and the ‘pacification’ exercises are not bored. And as long as they continue their work, so must we.”

So now I can sign the People’s Peace Treaty and clean my hands of the whole mess; so I wish. As I talk to people about the Peace Treaty, I sense among some a subtle feeling of antagonism toward the apparent arrogance of radicals, as if to imply one becomes and stays a radical because of the easy self-assurance such conformist non-conformity may offer and the easy answers we have to all problems.

What such people ignore is that the radical temper is often turned most radically upon oneself. Maybe what has been written here serves as an example.3

In early April, our Santa Barbara Peace Treaty Committee and the student government co-hosted a statewide People’s Peace Treaty conference at UCSB. We held a teach-in on the war and the recent invasion of Laos featuring Bob Scheer and Banning Garrett, showed films, and broke into smaller constituency-based and regional work groups to develop ways to promote the Treaty and to plan coordinated protests in May. Much to my exasperation, the gathering was marred by an infuriating outbreak of factionalism sparked by a Trotskyist sect called the Workers’ League, who condemned the People’s Peace Treaty based on their ideological disagreements with the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. My vague recollection is that the Workers’ League dogmatists dismissed the NLF as “bourgeois nationalists.”

In the course of archival research to refresh my memory of those days, I was delighted to discover Deep Cover, a memoir by former FBI undercover agent Cril Payne, who had once been assigned to spy on antiwar activists in Santa Barbara. Payne, one of the first agents out of the regional Los Angeles FBI office to grow a beard and long hair and adopt a sartorially plausible hippie-freak persona, claims in the book that he and three fellow agents (nicknamed “The Beards” by the FBI’s LA office) “participated in just about every demonstration held in Isla Vista or Santa Barbara that year [1971].” They also cultivated and trained “Arlo,” a strapping young local they hired as an informant. In one passage, Payne recalls one of the Beards’ first assignments:

The first statewide meeting we attended in Isla Vista was the People’s Peace Treaty Convention. The purpose of the convention was to ‘ratify’ a peace Treaty negotiated by a group of American antiwar activists with representatives of North Vietnam. It was hoped that overwhelming support from students could ultimately force the United States government to accept the Treaty. A noble though highly impractical cause.

After attending dozens of conferences, conventions, meetings and workshops, we observed that the only factor common to every gathering was that the participants could never reach agreement on anything. The various political groups were fiercely dogmatic… and fought constantly for influence…. Participants would argue for hours over whether the students or the workers would bring the revolution. I had a difficult time understanding why the Bureau was so concerned over the threat from the so-called “New Left.”4

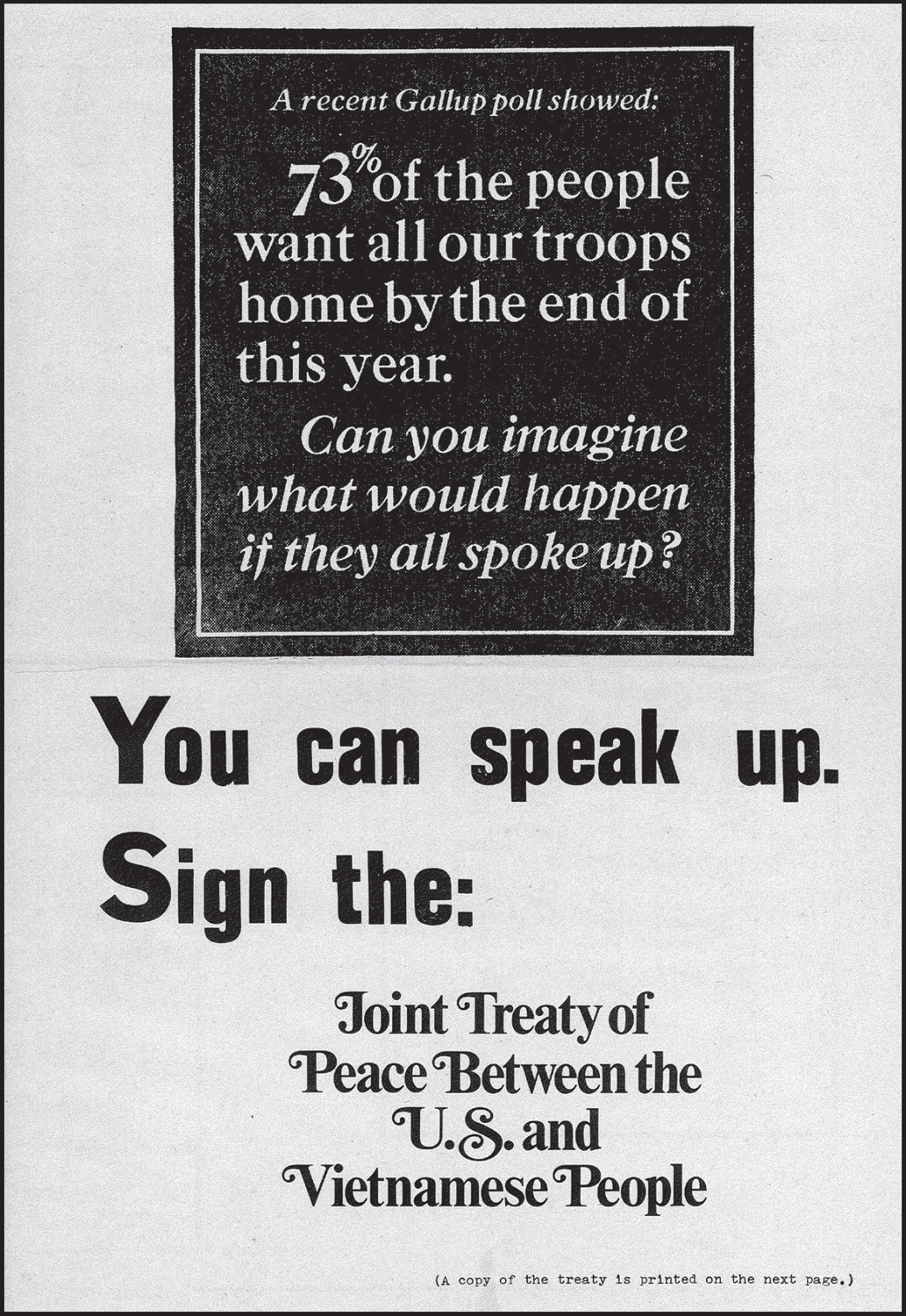

In March 1971, the Santa Barbara People’s Peace Treaty committee produced this poster-size leaflet and distributed it locally and to West Coast antiwar groups. On the reverse they reproduced a full-page ad published in the New York Times including a 3-point summary of the Treaty and a list of prominent endorsers.

Image courtesy of Becca Wilson.

My recollection is slightly different: In spite of the tedious, tendentious harangues and debates conference attendees were forced to endure, we did succeed in agreeing to a timetable for a week of protests in May. We also created an initial structure for local organizing and decided on ways to disseminate and seek ratification of the Treaty by a wide range of entities, from unions and churches to elected officials. At the conclusion of the conference, we sent a telegram of solidarity and support to the Saigon Students Union, who at that time were suffering a new round of vicious repression for their continuing, incredibly courageous work opposing the U.S. military presence in South Vietnam and U.S. support for the Thieu-Ky regime.

Working groups created at the conference each took on different tasks and/or agreed to coordinate all activities for one of the days of action planned for the first week in May. After the conference, many of us, especially those wanting to help coordinate the disruptive “no business as usual” actions, decided to break into smaller “affinity groups” or collectives so we could more safely guard against the undercover FBI agents and informers that we were certain were lurking in our midst. My feisty little tribe took responsibility for planning an action in front of a local plant engaged in war-related research and development.

Sometime during this period, I was approached by Keith Dalton, a reporter for the mainstream newspaper in town, the Santa Barbara News-Press. Though Keith was the paper’s police reporter, he sympathized with some of the Isla Vista/UCSB New Left activists frequently targeted by the cops. He warned me that according to his sources, the FBI was tailing me everywhere. I wasn’t a bit surprised, but having my apprehensions confirmed creeped me out and racked my already rickety nerves.

May

Here are the actions we managed to pull off in May:

Saturday, May 1: A Festival of Life with music and food is held in Isla Vista. Around 3,000 people march down State Street, the main street in Santa Barbara’s downtown, with many marchers passing out educational flyers about the People’s Peace Treaty and the war to people on the sidewalks. Probably two-thirds of the marchers are students and young people, but there is also visible participation from businesspeople, clergy, local unions and the Central Labor Council.

At a rally in a local park, after the usual passionate speeches, plus guerilla theater skits lampooning Nixon and his generals, a VVAW leader leads a solemn, silent ceremony. He lays his metal field helmet on the grass, and he and a group of fellow veterans cover it with medals and ribbons. The pile explodes into huge hot flames after someone douses it with homemade napalm: gasoline, liquid detergent—and a match. Later, about 50 protestors hold a vigil outside the county jail, in support of 100 inmates (about onethird of the total) who have gone on a hunger strike in support of our week of peace protests.

Sunday, May 2: A day of dialogue in Santa Barbara’s progressive and liberal churches, featuring the Treaty and the war.

Monday, May 3: A group of veterans in uniform pickets the Draft Board office. Activists pack the county Board of Supervisors meeting to speak out on an agenda item a member of our May Day coalition had succeeded in placing on the official agenda: consideration of the People’s Treaty and a suggested resolution urging that a date be set for withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Vietnam. An IVCC representative, antiwar vets, and others address the Board. Although a couple of the county supervisors say they agree the Vietnam War is “tragic” the Board refuse to take a stand, claiming they “lack jurisdiction.” Pointing out that plainclothes police officers were in the audience, a Santa Barbara News-Press article quotes one supervisor as saying the federal government is doing its best to “get us out of Asia with honor,” and another as saying, “I support the President.”

Tuesday, May 4: Veterans picketing at the Draft Board continues for a second day. Declaring that “the Vietnamese people are not our enemies,” activists flood the chambers of the Santa Barbara City Council, and urge it to endorse the People’s Peace Treaty. An IVCC representative says polls indicate 73 percent of Americans favor December 31, 1971 as the deadline for troop withdrawals and “the last day of dying and killing.” In addition to leaders of traditional peace groups such as Women’s Strike for Peace and Peace Action Council, several members of VVAW speak out. Underscoring the demoralization of the troops that was increasingly in the news, veteran John Lenorak (who would later become my boyfriend and much later, my brother-in-law), tells the Council that as early as 1966–67, when he was in Vietnam, he saw fragging incidents, fellow Marines addicted to heroin, and whole platoons refusing to go out on patrol. Another vet cites links between South Vietnam’s General Ky and the heroin trade. Pro-war folks also testify. A building contractor claims a majority of Americans “don’t want surrender.” A woman reads a letter denouncing our May 1 peace march from a group called Tax Action, claiming that aspects of the protest constitute “treason,” such as marchers carrying Viet Cong flags or displaying the U.S. flag ripped or upside down. In the end, the City Council votes unanimously to deny our request for a resolution supporting the Treaty and asking Nixon to set a date for withdrawal of all U.S. forces. In its unanimous motion to deny our request, the Council adds a statement deploring the “desecration of U.S. flags” during the May 1 march. As he’s walking out of the council chambers, one of my buddies turns and yells out, “See you at Nuremburg!”

Wednesday, May 5: At dawn, around 350 of us stage a very lively and disruptive demonstration in front of the General Motors AC Electronics plant in the town of Goleta, a couple of miles from the UCSB campus. When we arrive, a large phalanx of sheriffs is already there to greet us. Our research indicates that this facility has received more than $2 million to research and facilitate production of cluster bombs and rocket launchers. (For once, it appears the authorities agree with us. Asked by a Santa Barbara News-Press reporter why protestors singled out this plant, a Sheriff’s Lieutenant is quoted as saying “they are responsible for making weapons of genocide.”)

The mischievous collective I’m part of stages a “stall-in” to block traffic on the street outside the plant. In the middle of the busy boulevard, I and several of my friends suddenly stop our cars, jump out, and throw open our hoods, pretending that we’ve broken down (our vintage vehicles do in fact fit the part). Meanwhile, our comrades begin milling in the street and in the plant’s driveway, handing out flyers and copies of the Treaty to employees entering the plant by foot or car. We succeed in creating delightful pandemonium and quite a traffic jam, but not for as long as we’d hoped. The California Highway Patrol shows up, and officers on motorcycles do eventually manage to force us off the roadway. Awhile later, Sheriff’s Deputies in full riot gear use their two-foot-long billy clubs to shove our large crowd across the lawn fronting the plant, and into an adjacent parking lot. Eight people are arrested, among them several of my friends. My girlfriend Susan is slapped with felony assault on a police officer after throwing an orange at a guy we suspect is an undercover cop.

In downtown Santa Barbara later in the day, as other “no business as usual” events are unfolding, older members of Women’s Strike for Peace fan out on State Street. Dressed in mourning outfits and carrying flowers, they pass out flyers and copies of the Treaty to pedestrians and in stores. Other less polite actions that day include a sit-in in the middle of an intersection in downtown Santa Barbara, during which several hundred demonstrators succeed in halting traffic for nearly an hour. And down the street 50 protestors block the sidewalk in front of offices of General Electric Tempo, a “think factory that thinks the unthinkable—nuclear weapons, the arms race, the genocide against the people of Indochina. Over half of GE’s production is war-related,” says the leaflet that we distribute to passersby. When yet another group of bold demonstrators moves to block traffic on the 101 freeway, the state’s major north-south artery, an angry guy in a pickup truck guns his motor, speeds into the crowd, and narrowly misses several youths forced to leap backwards to avoid him.

July

A shocking turn of events: One day, a postman shows up at my door with a certified letter. It’s from the District Attorney’s office, informing me that I’ve been charged with three misdemeanors as a result of my participation in the May 5 demonstration outside the G.M. plant in Goleta—disrupting traffic, participating in an illegal assembly and resisting the lawful order of a police officer. Once I secure a lawyer and show up for the preliminary hearing, we meet with the prosecuting attorney and he shows us his evidence: several proverbial 8" × 10" glossy group photos of the protest with my face circled in red marking pen.

The short version of this long saga: I plead guilty to disrupting traffic. In exchange for this plea, the D.A. offers me the choice between either 45 days in jail, or two years’ probation, terms of which are that I’ll be instantly slapped with three months in jail and a hefty fine if I take part in any demonstration involving or resulting in illegal acts. I choose the jail term. In the Santa Barbara News-Press, the D.A. claims I’m playing the “martyr.” The paper quotes me as saying I don’t want anything to interfere with my constitutional right to continue protesting the war.

Doing my time in the Santa Barbara County jail is weird on more than one level. For one thing, all of the political prisoners—my friends arrested during our week of protests in May—have come and gone. I’m now the only one. One of my cellmates in our large group cell is Valeta, a heroin addict doing a year for sales of heroin.

Because of her “good behavior,” Valeta has been made a trustee, and much of her time is spent doing clerical work in the guards’ office. One day Valeta takes me aside to whisper a secret in my ear: the guards have instructed her to Xerox all of my incoming and outgoing mail, and send it to the FBI.

1972

A year or so later, I’m now co-editing an alternative weekly newspaper that I and a small collective of friends have created to counter the hegemony of the Santa Barbara News-Press. One day, my colleague Jim comes in to the office bearing a hot story—a personal account of espionage, Santa Barbara style. A few us gather around as Jim spins his amazing tale: one day, he and a couple of friends overhear a young woman they’ve been hanging out with talking on the phone. Something about her end of the conversation leads them to suspect the woman—her name is Valeta—may be working undercover. They confront her. It doesn’t happen overnight, but eventually, Valeta cops to the charge; she admits she’s getting heroin from the police in exchange for information about local antiwar and New Left activists.

Valeta!? I’m flabbergasted.

But the tale doesn’t end there: Valeta and her boyfriend Jimmy, also a junkie, insist they’re actually working as “double agents”—they’re feeding the cops harmless stuff about we rabble-rousers, while gathering truly useful data for us about police activities. Jim and company cautiously go along, but soon it becomes quite obvious that they’re being royally conned.

And now, it appears the best solution is that good old lifeblood of investigative journalism: an exposé. We need to publish a photo of Valeta and Jimmy, exposing them as two-bit snitches who pose a serious threat to The Movement.

For a few moments, Pham Van Dong’s parting words return for another sweet visit: “It will take courage, courage, courage. The rest will come by itself.”