Ingredients and Techniques

Theoretically, you could make “wine” or at least a liquid containing alcohol, from just sugar, water, yeast and some nutrients. But the whole point of wine is to preserve the nutritional content of the starting fruits or vegetables, so we’ll look at it from that point of view. Any fruit or vegetable can be used to make wine. Other than wine grapes, all fruits will require some amount of supplemental sugar. The juice of some fruits will require considerable dilution due to their high degree of acidity or astringency, and some will produce wines so tasty you’ll wonder why you can’t find them commercially. Others, like asparagus, will be downright unpalatable in some cases and suitable only for making marinades.

Wine grapes are the perfect fruit for making wine. All you need to do is crush them and they make the perfect amount of juice with the perfect levels of acidity and sugar. Every other fruit is imperfect in some way. While fruits other than grapes are imperfect, they can be made perfect through proper adjuncts and technique.

With air transportation for produce so prevalent, there are more fruits available in our local markets than I could ever list, and quite a few I haven’t tried because they are so expensive, such as starfruit and guava. In general, the higher the quality of the fruit, the higher the potential quality of your finished product. You will never make great wine from bad fruit—no amount of technique will improve its quality. But if you start with the highest quality fruit, there is at least the potential for creating great wine through solid technique.

You can use fruit in nearly any form to make wine: fresh fruits, dehydrated fruits, canned fruits, and frozen fruits. Fresh fruits and frozen fruits give the best results, and in many cases frozen fruits are superior to fresh because the process of freezing breaks down the cell walls to release more juice and flavor. Canned fruits often have a distinctly “cooked” taste that can detract from a wine, making it taste flat. They are best used for no more than half of the fruit in a wine. Wine-making shops sell specially canned fruits that come out better in wines than the canned fruit at the supermarket, but even these should constitute no more than half of the fruit by weight.

Dehydrated fruits retain their sugar, but have been subjected to oxidation and the loss of some of their more volatile flavor components. Usually, they are used in the form of raisins for purposes of adding some grape components to a wine so that it has a more vinous quality; dehydrated fruits in general, such as prunes and apples, are good for adding sherry-like taste qualities. Dehydrated banana is good for adding body to a wine such as watermelon wine that would otherwise be very thin. Very often, dehydrated fruits are sulfited to preserve their color. This is not a problem when they are added to a primary fermenter. In general, one cup of minced dried fruit will impart three ounces of sugar to the must, but this rule of thumb is no substitute for measuring with a hydrometer. Do keep in mind that making wine out of a dried fruit can concentrate the effects of that fruit, as I found to my chagrin with some prune wine I made.

Always use unwaxed fruit. Waxed fruits will create a mess rather than wine.

Fruits, you will discover, are pretty expensive in the quantities you’d use for making wine. For example, you’ll need twenty pounds of blueberries to make five gallons of blueberry wine. If you buy frozen organic blueberries at the supermarket for $3.69/lb, that means $73.80 just in fruit. Since you get twenty five bottles of wine from five gallons, that works out to just under $3/bottle, which is still a decent deal. Even so, it quickly becomes clear that your best bet is to either grow fruit yourself, go to a pick-it-yourself place or buy it in bulk from a farm stand. I pick the blueberries for my wine at Mrs. Smith’s Blueberries nearby, and it’s a lot more affordable. (You can also make wine in one-gallon batches so your initial outlay isn’t so much. This is a good idea when experimenting!)

Fresh fruits for country wines are primarily processed using only one technique. In this technique, the fruit is placed in a clean nylon straining bag in the bottom of the primary fermenter, crushed with cleaned/sanitized hands, with the difference in volume being made up by adding water. The water helps to extract the dissolved sugars and flavor compounds, and as fermentation begins, the alcohol created helps to extract the color. This technique is best suited to softer fruits that are easily crushed by hand, though it is used for practically all fruits for the overwhelming preponderance of country wines.51

Organic fruit juices can make a valuable adjunct to homemade wine

As an alternative, especially for harder fruits such as apples, I recommend using a high quality juice machine such as the Juiceman™ or Champion™. With these machines, the expressed juice goes into one container and the pulp goes into another. For darker fruits from which you want to extract color, such as cherries or blueberries, scoop the pulp from the pulp container into a nylon straining bag that you put in the bottom of the primary fermenter. (Note: Exclude the pits from stone fruits as they contain a cyanogenic glycoside that is poisonous.)

Juices

I have made very good wines from high-quality bottled juices. For example, two quarts of apple plus two quarts of black cherry with the sugar and acid levels adjusted and a hint of vanilla added will make a gallon of really great wine.

Bottled juice that hasn’t been treated with an additive that suppresses fermentation (such as potassium sorbate) can also be used to make wine. Keep in mind that something like the generic apple juice you can buy cheaply by the gallon is hardly more than sugar water and doesn’t make very good wine. But there is a big difference between brands, and sometimes you can make a really excellent wine out of a blended Juicy Juice™.

Bottled juices and juice blends from the natural food section of the grocery store are often 100% juice from the described fruit. These have been specifically formulated to retain the distinctive flavor of the fruit, and can be easily used as an addition to wines. You might want to be sparing in their use though, as they often cost as much as $10/quart.

Grape juice concentrates can help add “vinous” quality to a country wine, making its mouth-feel resemble that of traditional wines. These are special concentrates purchased from winemaking stores that have had the water removed under vacuum, and have been preserved with sulfites rather than through heat; therefore, they preserve a distinctive grape character. At roughly $16/quart (they make a gallon of must when water is added) they are expensive, but they make good additions as part of a must. They come in white and red varieties.

Vegetables

Vegetables are used for wine either by boiling them in water and including the water in the must, or by juicing the vegetables with a juice machine. Many vegetables, no matter how they are handled, will impart a haze to wines, but this effect is more pronounced when using boiled vegetables. This is because boiling tends to set the pectins while denaturing the natural enzymes in the vegetable that would otherwise break down the pectins over time. There’s no reason why you couldn’t try bottled vegetable juices so long as they haven’t been treated with a fermentation inhibitor, but the results can be pretty iffy when using brands that include added salt. Salt is added to vegetable juice to balance natural sugars for a tasty beverage. But when you use salted vegetable juice in wine, the sugar is converted to alcohol during fermentation but the salt remains. The results can be good for making marinade but decidedly not good for drinking. On the flip side, there’s nothing wrong with having a variety of self-preserved marinades ready and waiting!

Speaking of marinades, both wines and vinegars are commonly used for this purpose, and both are self-preserving. You can make very good marinades by fermenting mixtures that include onions, herbs, celery, parsley, and similar ingredients. With their high alcohol content, they will keep for decades.

If you aren’t making marinades but you are instead looking to make drinkable wines, both carrots and tomatoes can be excellent candidates for a wine. Carrots also blend quite well with apple. But don’t let the fact that I’ve never made okra wine deter you if you want to give it a try.

Herbs and Spices

Though spices are not added to wines very much today, in past times spices were quite expensive so heavily spiced wines were an indicator of wealth and status. Unlike the traditional wine makers of France, as a home wine maker you don’t have to contend with the traditional rules for making wine. One bonus is that you can add anything you’d like. You can add mulling spices to an apple wine, a hint of vanilla and cinnamon to a blueberry wine, and just a touch of rosemary to a carrot wine. The only rule is to make something that you and your friends will enjoy drinking, so if spices can enhance a wine to your tastes, then there’s no reason not to use them. However, just as with food, it can be easy to over-do spice. Better too little than too much.

When adding spices, use whole rather than powdered ingredients. For one thing, powdered spices tend to have lost some of their volatile flavor components and will give inferior results. For another, they often form a haze in wines that is harmless but unsightly.

The technique for use is straightforward. Put the chosen spices in a spice bag, and lightly boil the bag in a quart of sugar water for ten to fifteen minutes, then discard the bag. Allow the spiced sugar water to cool to room temperature before adding to the must.

| Spice | Goes best with | Amount to use |

| Peppercorns | Used to add warmth to most wines | 5–10 whole peppercorns per gallon |

| Cassia Buds | Apple, blueberry, cherry, and most fruit wines | 10–30 buds per gallon |

| Cinnamon | Fruit wines | 1 stick per gallon |

| Cloves | Fruit, vegetable, and grain wines | 3–6 cloves per gallon |

| Allspice | Fruit, vegetable, and grain wines | 4–10 berries per gallon |

| Nutmeg | Fruit and vegetable wines | No more than ½ meg per gallon |

| Ginger | Best in lightly flavored wines such as apple and carrot | 2–8 ounces, grated |

| Star Anise | Fruit wines | 1 star per gallon |

| Vanilla | Fruit wines | 1 vanilla bean or less per gallon |

Because yeast contains enzymes that turn many forms of sugar into a sort more easily used, any common source of sugar will have the same result in terms of alcohol production. You can use granulated cane sugar, dextrose, glucose, fructose, honey, molasses, brown sugar, maple syrup, high-fructose corn syrup, dried fruits, concentrated fruit juices, and more.

Though the source doesn’t matter in terms of creating alcohol, it can make a big difference in terms of taste—for example, many of the chemical compounds that make honey or brown sugar have a distinctive taste and aroma which will be preserved in wines that include them. For this reason, I would recommend against using brown sugar or molasses.

Glucose, dextrose, fructose, and sucrose (cane sugar) are all treated identically by yeast. If the sugar isn’t in a form the yeast can use, the yeast employs an enzyme called invertase to change it into a usable form. Nothing is gained by using the more expensive fructose from a health food store over an inexpensive bag of granulated sugar from the grocery store. None of these contribute flavor to the wine, and simply serve as a source of sweetness or alcohol. They are a good choice for wines in which you want the tastes and aromas of the primary fruit to dominate their character.

Bottled juices and juice concentrates can also be used as a source of sugar, especially given that sugar is their primary solid constituent.

Containing a wide array of minerals, amino acids, and vitamins, honey is a tasty addition to many wines. A number of cultural traditions (including the honeymoon) have grown up around honey wines. Strictly speaking, a wine made from honey alone is called mead. Wine that combines honey with apples is called cyser, whereas wine made from honey and any other (non-grape) fruit is called melomel. Wine made from honey with added herbs is called metheglin, and wine made from honey and grapes is pyment.

When making mead variants, the source and quality of the honey you use makes a difference in the taste of the finished product. The generic blended honeys in the supermarket are fine when the honey is primarily used as a source of sugar. If you are making mead, however, blended honey is useless because it has been pasteurized and homogenized until it is nothing but sugar. If the tastes and aromas of the honey will be important to the end product, use a single-source honey from a bee keeper. The nectar that the bees collect positively affects the mineral content and flavor of mead. Clover, alfalfa, orange blossom, wildflower, and mesquite are just a few of the types of honey available; in general, darker honeys impart stronger flavors. You can get single-source and wild honeys from a local bee keeper, order them over the Internet or, if you are ambitious, start keeping bees yourself 52 and create your own honey.

Cleanliness and Sanitation

Before I get into the details of making wine, I want to delve a bit into cleanliness and sanitation, as these are crucial for a successful outcome. You don’t need a laboratory clean room or a level 3 hazmat facility to make wine. You can make wine in your kitchen or any room in your home. But you need to be attentive to detail. Everything that touches your must, wine, or wine-in-progress must be clean and sanitized.

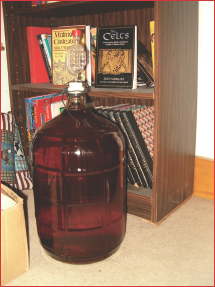

“Clean” simply means “free of visible dirt or contamination.” Dish soap and water are adequate cleansers. Wine bottles, fermentation vessels, wine thief, plastic tubing, and hydrometer along with all utensils that touch your wine need to be cleaned. Sometimes, all that is needed is to add some soapy water and shake. Other times, as with carboys, you may need to use a special brush. For subsequent sanitation procedures to work, the surfaces must first be clean. Once they have been cleaned, they should be thoroughly rinsed.

To sanitize the equipment, all surfaces that will touch the must or wine should be rinsed or wiped down with a sanitizing sulfite solution. Don’t rinse afterwards. For bottles, vessels, and carboys you can add a portion of the sulfite solution and swish it around thoroughly so that it contacts all surfaces, and then pour it back into your container of solution. For other utensils, soak paper towels in sanitizing solution and use those towels to wipe them down immediately before use.

Your hand siphon and tubing might look to pose a problem at first, but there is an easy technique for keeping them clean. For this technique, you need two clean plastic gallon jugs that were previously used for water. Put one with soapy water on your counter and the empty one on the floor. Now, use your siphon to pump the soapy water all the way up into the tube and through the tubing into the empty container on the floor. Then, switch the containers and repeat the process until the equipment is clean. Empty out the containers and rinse them thoroughly. Next, put the bottle of sanitizing solution on the counter, and siphon that into the empty container on the floor. Make sure to wipe down the outside of the equipment and tubing as well, as these may contact the wine.

Making the Wine Must

As noted previously, your wine must doesn’t have to be made from a single source. You can use apples mixed with pears, carrots mixed with apples, juiced table grapes combined with bottled cherry juice, or whatever strikes your fancy. As long as you use good sanitation and technique, the results will be at least as good as most wines you can buy.

Some fruits are either highly acidic or highly tannic to such an extent that you wouldn’t want to use their extracted juice exclusively to make wine because the results would be too sour or bitter. In those cases, only a portion of the must is made from that fruit, and the rest is made up from water or other juices.

What follows is a recipe table that indicates how many pounds of a given fruit to use in making a gallon of wine from that fruit, how much tannin to add to that wine per gallon, and any other adjuncts that I’d recommend. Any deficit in juice to make a gallon is made up with water.

The Primary Fermentation: Step-by-Step

1. Start with fruit juice obtained as described earlier in this chapter.

2. If needed, add enough water to the fruit juice to equal the amount of wine you wish to make. (It is helpful to add previously-measured amounts of water to your primary fermenter in advance and use a magic marker to mark gallons and quarts on the outside of the vessel for easy reference.) I use bottled water because my well water is sub-optimal, but if you have good water where you live, tap water is fine. Don’t worry about whether or not your water is chlorinated, because the Campden tablets we’ll be adding later serve to remove chlorine from the water.

3. Use your hydrometer to measure the specific gravity (SG) of the must. You are aiming for an SG of between 1.085 and 1.110, but in all likelihood your must measures much lower. Add the required amount of sugar or honey to your must. This will slightly increase the volume of your must, but that’s fine.

4. Use your acid testing kit to test the acidity of your must. If needed, add acid. Try to use the specific acid (or acid blend) that will best enhance the character of the fruit. For example, malic acid will enhance apples and pears whereas citric acid will enhance watermelons and tartaric acid will enhance grapes. If you are in doubt, use an acid blend made up of equal parts of the three acids.

5. Add one teaspoon of yeast energizer for each gallon of must.

6. Add pectic enzyme as directed on the container, or double the amount if the recipe table specifies doing so.

7. Add tannin as appropriate for the fruit being used. (This is described in the accompanying recipe table.)

8. Crush and add one Campden tablet dissolved in a bit of juice per gallon of must. Vigorously stir the must.

9. Cover your primary fermenter, and plug the hole with a bit of cotton ball to keep foreign objects out. Wait 24 hours.

10. Vigorously stir the must to oxygenate. Once movement ceases, sprinkle yeast from the packet over the surface of the must. Do not stir.

11. Place the cover on the fermenter, and plug the hole loosely with a bit of cotton ball.

12. Allow to sit for a week. During this time, you should smell the fermentation. Also, it may foam heavily and come out through the hole in the lid. If it does, clean up on the outside and insert a new cotton ball. After the week, replace the cotton ball with an air lock filled with sanitizing solution.

13. Allow to sit for another week or two, until the air lock only “bloops” once every few seconds. This marks the end of the primary fermentation phase. Once the primary fermentation phase has ended, rack as soon as possible. If it sets for more than a couple of days, the dregs at the bottom (known as lees) will impart bad flavors to your wine.

Your First Racking: Step-by-Step

1. A day before you plan to rack, move your primary fermenter to a table or counter top. (By doing this a day in advance, you give any sludge stirred up by movement a chance to settle.) Put a wedge, book, block of wood, or something else from 1” to 2” high underneath the fermenter on the edge that is away from you. This will allow you to sacrifice the smallest amount of wine possible with the lees.

2. Clean and sanitize your racking tube, tubing, and your secondary fermenter and get your rubber stopper and fresh air lock ready. Put your secondary fermenter on the floor in front of the primary fermenter, and then carefully remove the lid from the primary fermenter, creating as little disturbance as possible. Put a bit of the wine in a sanitized glass, and dissolve one crushed Campden tablet per gallon, then add it back to the wine.

Racking requires a bit of coordination but with practice it comes easily.

3. Put the plastic tubing from your racking setup in the secondary fermenter and the racking tube in the primary fermenter. Keeping the racking tube well above the sediment, pump it gently to get it started. It may take a couple of tries. Gently lower the racking tube as the liquid level diminishes. Watch the liquid in the tube very carefully. The second it starts sucking sediment, raise the racking tube up to break the suction.

4. Place the rubber stopper with an air lock filled with sanitizing solution in the secondary fermenter. Using a carboy handle if necessary, move the secondary fermenter to a location out of sunlight where even temperatures are maintained.

5. Immediately clean and sanitize your primary fermenter, racking tube, and tubing and stow them away. If you don’t clean them immediately they will likely be ruined.

The Secondary Fermentation: Step-by-Step

1. Wait. And wait. Then wait some more. Patience, I have been told, is a virtue. After your first racking from the primary to secondary fermenter, the yeast will lag for a couple of days while it tries to catch up. Allow the secondary fermenter to sit unmolested until: the wine starts to become clear, you have more than a dusting of sediment at the bottom of the container, or the air lock only operates once every couple of minutes. This will likely take about a month. Because the secondary fermenter sits for so long, don’t forget to check the airlock periodically and top up the sanitizing solution in it so it doesn’t evaporate and leave your wine vulnerable.

2. The day before racking, sit the secondary fermenter up on a table or counter, and tilt it using a book or other wedge, as before.

3. Boil some water in a pot on the stove and allow it to cool to room temperature while covered. Clean and sanitize another fermentation vessel as well as the racking tube and tubing. Place the sanitized vessel on the floor in front of the secondary fermenter, put the plastic tubing in the vessel, and put the racking tube in the secondary fermenter. Operate the racking tube and transfer the wine from the old vessel to the new. Add one Campden tablet dissolved in wine for each gallon of wine.

4. Likely, there is an air space between the wine and the top of the new vessel. This will expose too much surface area of the wine to oxygen and potential infections. Pour in the sterilized water until the wine is just up to the neck.

5. Clean the rubber stopper and airlock, sanitize them, re-fill the airlock with sanitizing solution, and install them on the new secondary fermenter. Put the secondary fermenter in a location without sunlight and with even temperature.

6. Thoroughly clean and sanitize the empty secondary fermenter, the racking tube and the tubing.

The secondary fermentation in this vessel is almost complete.

7. Now it is a waiting game. Over weeks and months your wine will ultimately cease to ferment, and the haze within the wine will settle onto the bottom of the container. Keep an eye on the wine. Anytime a substantial sediment develops, rack the wine again and top up with sterilized water. Make sure the airlock doesn’t go dry and permit foreign organisms to enter. Depending on ingredients, you may not have to rack again or you could have to rack one to three more times.

8. Once the wine has gone at least three months without requiring racking and is crystal clear, it is ready for bottling. You can allow it to age in the fermenter as long as you’d like—even several years.

Bottling Your Wine

1. Gather, clean, and sanitize the wine bottles that will be accepting the wine. You will need five bottles per gallon of wine. Boil an equal number of corks for 15 minutes, and then allow them to sit in a covered pot. Clean and sanitize your corker.

2. Rack the wine, but do not add water to top off on this final racking. Add one Campden tablet per gallon by crushing the tablet and dissolving in a bit of wine and then adding that wine into the new vessel.

3. If you want to add potassium sorbate to prevent re-fermentation, dissolve that also in the wine and add back into the new vessel. Use ¼ tsp per gallon of wine.

4. Place the secondary fermenter holding the wine on a table or counter top, tilting as before.

5. Arrange the bottles on a towel on the floor in front of the fermenter and install the plastic hose clamp on the plastic tubing so you can turn off the flow of wine when switching from bottle to bottle.

6. Put the plastic tubing in a bottle and the racking tube in the wine, pump the racking tube and start the flow of wine, pulling the tube higher in the bottle as the level of the wine increases. Stop the flow of wine when it is about half an inch into the bottom of the neck of the wine bottle. Put the tube in the next bottle and repeat the process until you run out of wine or there are no more bottles to fill.

7. One at a time, place the bottles on a solid floor, and use your corker to install one of the sterilized corks. Only work with one bottle at a time. As each bottle is corked, set it out of the way. Repeat until all of the bottles are corked.

8. Clean and sanitize your fermenting vessels, racking tube, and plastic tubing.

9. Now you can make and apply wine labels if you wish.

10. Enjoy at your leisure or give as a gift.

Bottled blueberry wine. Magnificent!

Creating Your Own Recipes

Most wine books are full of recipes. I’m sure they are useful, but I think it is more useful to understand how they are created so you can make your own recipes based upon what you have available. One of the reasons I went into so much detail in the chapter on the science of making wine is so you’d have all the tools you need to be self-sufficient.

When making a new wine for the first time, it is best to make it in a one-gallon batch. Overall, larger batches tend to come out better because they are less susceptible to temperature fluctuations, but I’ve made plenty of excellent wines in one-gallon batches, and the smaller amount may be less intimidating to a beginner.

In addition, even the cheapest wine ingredients are expensive at the scale of a five-gallon batch, so making a one-gallon batch is also best for experimental recipes. Reserve the larger five-gallon batches for tested recipes you know you’ll be making for long-term storage or gifts. Some wine makers never make batches larger than a gallon, and they are quite happy with their results.

So let’s look at the first critical decisions involved in making a wine recipe.

• Dominant and any secondary or tertiary fruits or flavors. This decision is purely aesthetic, and if you are someone with chronically bad taste you might consider consulting a friend or loved one for guidance. For example, I might want to make a wine with apple dominant, mulling spice secondary and honey tertiary. It would be rather daring as there would be little residual sweetness to balance the spice, so instead I’ll make the apple dominant, honey secondary and mulling spice tertiary. Another example would be a wine with sweet cherry dominant and concord grape secondary.

• Check the tannin levels of each fruit. Any fruit that is high in tannin cannot be more than half of your must. If you want the fruit to be dominant anyway, you’ll have to choose something unassertive such as generic white grape juice as a secondary. For example, if I want to make a wine with blueberry dominant, because blueberry is highly tannic, I am limited to four pounds of blueberries per gallon and will need to use adjuncts that won’t overshadow the blueberry, such as white grape juice to make up the difference in volume.

• Check the acid levels of each fruit. Though the tables I’ve included are not a substitute for actual measurement, you can use them to get an idea that lemons are too acidic to constitute a major proportion of a wine must and that watermelon would need acid added. If the level of acid in the fruit is greater than 9g/L, then the quantity of that fruit should be limited to avoid excess acidity.

• Sugar level. Get a general idea of how much sugar will be in the major fruit ingredients, and how much will need to be added. Also, decide what form that sugar will take.

• Spicing. Look at the earlier tables when deciding how much spicing to add, if any.

• Pectic enzyme. Other than straight meads, all recipes will need pectic enzyme. Review the tables to see if the amount used is according to package directions or needs to be doubled.

• Yeast. Decide what type of yeast to use based upon its characteristics, and include yeast energizer in the amount recommended on the package.

One Gallon Example: Cherry Wine

Few can resist the idea of cherry wine, so it’s a good start for a recipe. I’ve made cherry wine during the winter months and used a combination of bottled cherry juice, frozen cherries, and other adjuncts.

• I would like my dominant flavor to be cherry, my secondary flavor to be grape, and my tertiary flavor to be vanilla.

• Checking the tables, I see that cherries are high in tannin so they can’t form more than half of my must, and they are high in acid too. So I will use one quart of bottled organic 100% black cherry juice, and one ten-ounce package of frozen sweet cherries, and make up the difference with organic white grape juice. Because less than half the recipe will have the higher tannins of cherry juice and the remainder of the recipe will come from white grape juice, tannin is likely to be a bit on the low side, so I’ll add a quarter teaspoon of tannin.

• The two primary acids in cherries are malic and citric in that order, so if an acid test shows more acid is needed, I’ll add a 2:1 mixture of malic and citric acids.

• Because I’m using bottled juices and frozen cherries with nutritional labels, I can add up how much sugar would be in the gallon: 200g from cherry juice, 42g from frozen cherries, and 480g from grape juice for a total of 722 grams. Converted to ounces that is 25.5 ounces. Looking at the hydrometer tables, I see that I need 31.6 ounces of sugar for a starting gravity of 1.090, so I figure I’ll need about six ounces of sugar, though I will test with a hydrometer to be sure.

• Looking at the spicing table, and not wanting to overpower the cherry, I am including one vanilla bean in the primary fermenter.

• A lot of yeasts are available, but Montrachet looks like a really good match for what we’re making.

So the final recipe looks like this:

Winter Cherry Wine

1 quart organic black cherry juice

1 ten-ounce package of frozen sweet cherries

3 quarts organic white grape juice

6-8 ounces of sugar, based on hydrometer test

1 vanilla bean

¼ tsp yeast energizer

¼ tsp tannin

2:1 blend of malic/citric acids as needed

1 packet Montrachet yeast

51 If you are using purchased fruits, please make sure they are un-waxed. The wax that purveyors use to make fruits look pretty will turn your intended wine into a useless mess.

52 In my opinion, I don’t have enough experience to write a book on beekeeping, however I have found Kim Flottum’s The Backyard Beekeeper to be very good. If you are interested in keeping bees for honey, I highly recommend it.