The scene is a Lonely Place, and the time the Present.

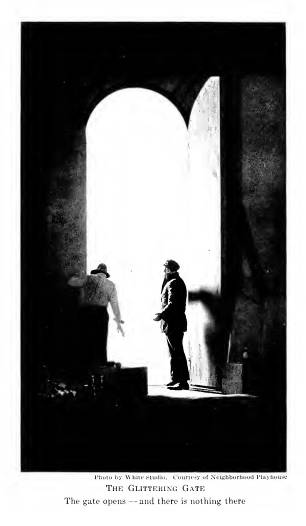

The Lonely Place is strewn with large black rocks and uncorked beer-bottles, the latter in great profusion. At back is a wall of granite built of great slabs and in it the Gate of Heaven. The door is of gold.

Below the Lonely Place is an abyss hung with stars.

The two characters of the piece are Jim, lately a burglar, for he is dead, and Bill, likewise deceased, who was a pal of Jim’s on earth.

Jim was hanged and Bill was shot, and the marks of their recent ordeal are still upon them. Jim has been dead the longer, so that he is there first. Bill finds him uncorking empty beer bottles endlessly and throwing them away, as he enters and knocks on the Gate of Heaven. Each time that Jim finds himself deceived by the empty bottles faint and unpleasant laughter is heard from somewhere in the great void. Bill recalls to Jim the little things of their life together and gradually Jim remembers. Finding the great door immovable before him Bill recollects that he has still with him his old jemmy, “nut-cracker”, so with it he tries to drill open the huge Gate of Heaven. Jim takes little interest in the endeavour until suddenly the door begins to yield. Then they both give themselves up to imagining all the wonders that will confront them on the other side of the closed door. Bill is sure that his mother will be there, and Jim thinks of a yellow-haired girl whom he remembers as a bar-maid at Wimbledon. Of a sudden the drill goes through and the great door swings slowly open, and — there is nothing there but the great blue void, hung with twinkling stars.

BILL, (staggering and gazing into the revealed Nothing, in which jar stars go wandering) Stars. Blooming great stars. There ain’t no heaven, Jim.

(Ever since the revelation a cruel and violent laugh has arisen off. It increases in volume and grows louder and louder.)

JIM. That’s like them. That’s very like them. Yes, they’d do that!

(The curtain falls and the laughter still howls on.)

This play has been pointed out as a bit of rare cynicism on the part of Lord Dunsany, but I am inclined to think that this opinion is unjustified. What he has done is simply that which he never tires of doing, of showing man in his eternal conflict with the gods. The Gate of Heaven cannot be forced open with a jemmy, or if it is there will be found nothing on the other side. Bill and Jim are both materialists, and having broken both the law of God and man all their lives, it is thoroughly in keeping that after death they should adhere to their old beliefs, that there is nothing too strong or too sacred to be forced to serve their turn. Not to try to force the door would be wholly out of character for them, but to force it and to find heaven on the other side would violate our sense of the eternal fitness of things. Surrounded by empty beer-bottles, fitting symbols of their material life, and hounded by the mocking laugh of Nemesis, Bill and Jim can only vent their spleen in a last bitter outcry against the eternal. The old and endless balance of things is achieved, and the law is accomplished.

The play is open to several interpretations and therein lies its greatest weakness. The issue is not clearly defined and it is only in the light of Dunsany’s other work that we are able to attempt a logical elucidation. A mythology such as Dunsany’s presupposes a certain element of fatalism when man comes in contact with the cosmic force. It must be remembered too that Dunsany is a great imaginative genius, — have I not deplored his lack of interest in man as related to man? — and that imagination is a wholly mental quality. Any emotion we get from Dunsany is not one based on human attributes; for the most part it is purely æsthetic, a rapture at the beauty of his conceptions, and at his manner of expression, or a terror at the immensity and grandeur of what he shows us. Herein he is at one with the Greek dramatists, and this attitude on his part has been laid down by Aristotle as a law of tragedy centuries ago. That is why we find so little human sympathy shown in his treatment of Bill and Jim. How easy it would have been to have made this play a maudlin diatribe! But Dunsany’s point of view on the problem is purely dispassionate, entirely that of an artist — and an aristocrat! And after all the little play must not be taken too seriously. It has a story to tell, and with Dunsany the story is paramount always. There is no need to attempt to read in a hidden meaning. Yeats might have written the play and if he had done so we should doubtless have had a second version of “The Hour Glass” or something closely akin to it. Indeed the influence of Yeats on this first play of Dunsany’s is not to be ignored.

Dramatically “The Glittering Gate” leaves much to be desired. It most certainly furnishes an excellent example of the law of surprise, and it even provides suspense, a much more vital element, and one which is not always to be found in Dunsany’s plays. How often it has been said that a dramatist must not keep anything from his audience! A genius may do all things, and as a rule Dunsany prepares us for his surprise so effectively that in the very preparation an element of suspense is created. It is interesting to observe that Dunsany here avoids an error which marks a weak spot in two of his later and bigger plays; that is, he does not attempt to bring the gods on the stage. The mocking laughter is much more mysterious and terrible when its source in unknown.

The dialogue is excellent. The language that the two dead burglars use is perfectly natural and in character, albeit the situation is grotesque. This very incongruity is highly dramatic in itself. Through the dialogue, too, runs a vein of gentle irony, as there does through every Dunsany play. Each character is developed along individual lines. Jim is frankly a cynic; Bill is more trusting — but Jim has been dead the longer.

In dénouement the play is masterly. The climax is led up to without hesitation and when the moment comes the blow is struck with deadly accuracy. Then the play is over. No further time is wasted in “past regrets or future fears.”) It is not a very good play on the whole, but considering the circumstances under which it was written it is beyond question an extraordinary play. I think it is a better play than “The Queen’s Enemies”, which was written much later and which was successful in production. But “The Glittering Gate” will remain always one of the least popular of Dunsany’s plays, for while the dialogue, the humour, the characterization, the dénouement are all done well and with infinite finish, the purpose of the play is undoubtedly vague, and no matter how capable it is of elucidation its lack of clarity detracts from the force of the piece. It could not be otherwise. The play depends on the situation and upon the dialogue to hold the interest of the audience; there is no actual opposition to the characters, none of the immediate and personal conflict for which the modern audience has been taught to look. To some people this will always be a lack in Dunsany’s plays, but they could not have been written in any other way and written as well. The impotency of man is much more strongly shown when he is placed in conflict with a gigantic indefinable force; as soon as that force suffers embodiment, it is brought down to man’s level, and the whole conception is destroyed.

“The Glittering Gate” stages well, and acts well; it is very short even for a one-act play, but its lack of definitiveness keeps it from being classed with the later and more forceful work of the author. None of Dunsany’s plays could be described as robust; they are too delicate, and too full of finesse for that, but “The Glittering Gate” is not even vital. And notwithstanding all that, it is a most extraordinary play.