The scene is outside the King’s great door in Zericon, and the time is some while before the fall of Babylon. Two sentries guard the door and talk meanwhile of the heat and the cool of the near-by river. They talk also of the great King, and one of them feels a sense of menace as if some doom hung heavy. A star has fallen, and that may be a sign. A little boy and girl come in. The boy has come to pray to the great King for a hoop, but he cannot see the King so he prays to the King’s door instead.

BOY. King’s door, I want a little hoop.

The girl tells of a poem she has made and then proudly she recites it.

I saw a purple bird

Go up against the sky

And it went up, and up,

And round about did fly.

BOY. I saw it die.

GIRL. That doesn’t scan.

BOY. Oh, that doesn’t matter.

The King’s Spies cross the stage, and the girl is frightened. The boy tells her that he will write her verses on the King’s door, and at this she is greatly delighted. And so he writes the verses, appending the last line he added. The girl again protests, but the line is written.

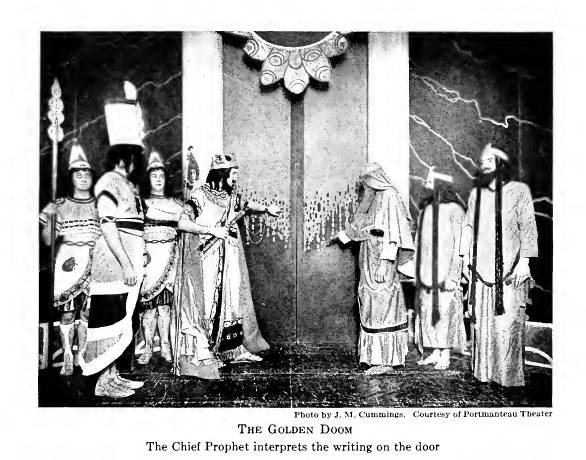

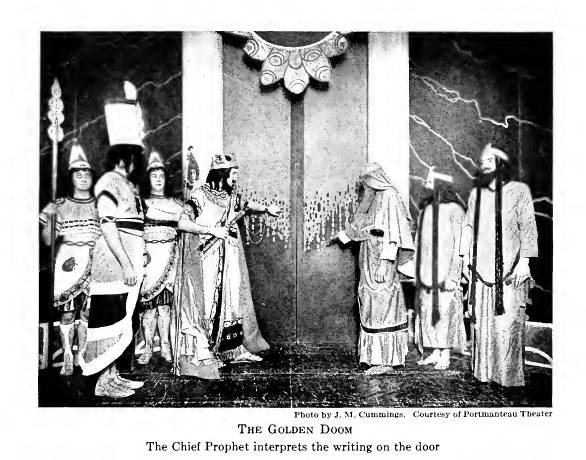

The sentries have hardly noticed the children, but now they hear the King coming so that they drive the youngsters away. The King comes with his Chamberlain, and as he nears the door he sees the writing on it. He questions the sentries but they say that no one has been near the door; it does not occur to them to mention the children. The King fears that this writing may be a prophecy. The Prophets of the Stars are summoned and are commanded to interpret the prophecy of the writing on the King’s door. They cannot do so, but each one silently covers himself with a great black cloak, for they believe the prophecy to be a doom. The Chief Prophet is summoned. He reads the writing and says that the King can be no other than the purple bird, for purple is royal; he has flown in the face of the gods and they are angry. It is a doom. The King offers a sacrifice. He says that he has done his best for his people; that if he has neglected the gods it was only because he was concerned with the welfare of his subjects on earth. The King and the Chief Prophet discuss the most suitable sacrifice, and finally decide that the King’s crown as a symbol of his pride shall be offered. The King asks only that he may rule among his people uncrowned, and minister to their welfare. So the crown is laid on the sacrificial block before the King’s door, and as the night comes on and it grows dark so that the stars may be seen, everyone goes away.

BOY. (enters from the right, dressed in white, his hands out a little, crying) King’s door, King’s door, I want my little hoop.(He goes up to the King’s door. When he sees the King’s crown there he utters a satisfied) O-oh! (He takes it up, puts it on the ground, and, beating it before him with the sceptre, goes out by the way that he entered.)

(The great door opens; there is light within; a furtive Spy slips out and sees that the crown is gone. Another Spy slips out. Their crouching heads come close together.)

FIRST SPY. (hoarse whisper) The gods have come!

(They run back through the door and the door is closed. It opens again and the King and the Chamberlain come through.)

KING. The stars are satisfied.

So the play ends, on the high note, the major chord always.

The play like others of Dunsany’s represents the expression of an abstract idea, and that idea not a particularly dramatic one. Again we have the cosmic, the godlike viewpoint, detached, impersonal and vast. A King’s crown and a child’s hoop are weighed against each other in the scale, and are found to be of equal importance in the scheme of things. We learn that it is not always the great things, but sometimes the smallest things that overthrow whole kingdoms, that prophets are by no means infallible, and that the gods may speak to us through the mouth of a child.

The “Golden Doom” is well constructed. It builds from the very outset to a triumphant conclusion. But it lacks opposition, conflict. Man is neither opposed to man nor even to the gods. A sacrifice is made; will does not assert itself but bows to the inevitable. As a study of a situation, as the exposition of an idea the play is in its way a masterpiece, but the fact that the forces which are suggested in the action are not contending thins the piece from a purely dramatic standpoint. It is the poet rather than the dramatist who speaks in “The Golden Doom.” It may be observed too that it is no personal problem with which we are confronted; it rarely is with Dunsany. We do not feel, nor is it desired that we should feel, a sense of personal sympathy for the Boy praying for his little hoop, or for the King laying his crown on the sacrificial block. It is Boyhood in the mass, nay, even in the abstract with which we are called upon to sympathise; it is the idea of Majesty which we are asked to pity. It is Man in the conglomerate whole with which we are dealing; not an individual man. It is necessary that this should be well understood, for it is one of the basic principles of Dunsany’s work, and it is summed up when I repeat that he is more interested in ideas than he is in people. It is never an isolated individual problem which he attacks; it is rather some one question which is peculiar to humanity as a whole.

It is interesting to observe that while Dunsany does not provide conflict in this play he does provide the next thing to it, contrast, and that in a most effective manner. The whole episode of the children played against the background of royalty with its spies and its prophets is immensely ironic. The point of view of the child, too, with its perfect and wholly unconscious logic, becomes delicious when placed in juxtaposition to the complex outlook man has built for himself. To understand this play is to understand Dunsany. Invariably he is a scoffer at the subtleties of adult philosophy, and a strong adherent of the clear, unsophisticated point of view of the child. He reduces sophistication to its basic premise of sophistry times without number, only to rise and to attack once more from another direction.

Dramatic technique is largely a matter of dramatic instinct, mixed with a goodly portion of common sense. Dunsany does not pretend to be a technician, but observe how carefully, and yet how easily, we are shown that the King’s great door is sacred and must not be touched. A stranger from Thessaly enters at the very beginning of the action and approaches the door. The sentinels warn him off with their spears, and after a moment he wanders away again, having provided the necessary exposition in the most natural manner possible. The atmosphere is heightened, and we hardly realize that we have learned anything of importance. See too how the note of menace is struck at the very outset by one of the sentries who feels a doom and a foreboding. It is not unduly emphasized, but it is there and we at once feel the force of its suggested terror. From then on we wait, sure that a crisis of some kind is at hand. As I said, the play ends on a major chord, but it does even more than this; it ends at the very moment when it should end, neither too soon nor a moment overtime. This point is true of Dunsany’s plays; they begin at the one inevitable moment when they should begin, and they end in a like manner. This is not only true of the plays as a whole, but it is true of every separate scene, and of every speech in the scenes. They are all timed to the minute. The dialogue of Dunsany has been compared with that of Maeterlinck, but the comparison is superficial. Maeterlinck’s dialogue is often so vague as to be practically imbecilic in effect, while the dialogue of Dunsany is always terse and to the point; not one word is wasted, there is never a shadow of doubt as to the exact meaning, and every speech carries the action definitely forward. With Maeterlinck too all the characters speak in the style of Maeterlinck, whether they be prince or peasant; there is no attempt to give them a colloquial value. It is here that Dunsany most clearly shows that with his marvelous imagination he has combined the most acute power of observation. His characters are as real as any to be found next door or on the high-road. It is only the situations which are grotesque, and this very combination of the real and the unreal makes for dramatic effect in a manner of which Maeterlinck for all his genius could not dream. Dunsany has observed and noted, and the results of that observation are as true to life as any preachment of Ibsen’s; with Dunsany it is only his terminology that is strange.

For sheer beauty of thought and of expression “The Golden Doom” ranks high among Dunsany’s works. It is full of wonderful color, and of that magic atmosphere of which only Dunsany is master. It has a story to tell, and that story is one of the great ones of the world, albeit that the theme is perhaps more suited to the poem than to the play. That is the only flaw in an otherwise faultless bit of work, that the poet has for a moment driven the dramatist to a secondary position. But the work was well worth doing, and who but Lord Dunsany could have written “The Golden Doom”?