Dunsany says of this play that comparing it to “The Gods of the Mountain” is like comparing a man to his own shadow. That sums up the case very well. “A Night at an Inn” is indeed a shadow, an echo of the greater work.

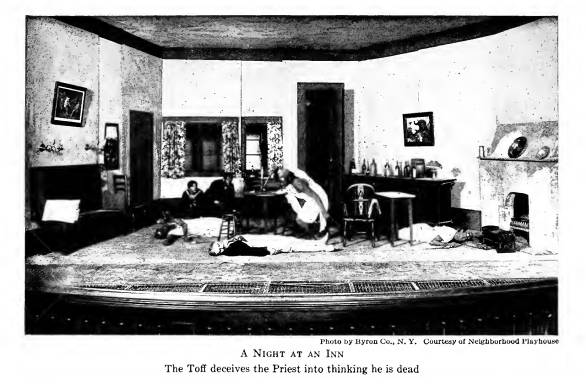

The curtain rises on a room in an old English Inn. The Toff, a dilapidated gentleman, is there with his three sailor followers. We learn from the ensuing conversation between the three (the Toff does not enter into the discussion) that a short time ago the party raided an Indian temple, and robbed the idol of its single eye, a huge ruby. Their two companions were killed before they left the country, and even now the three priests of Klesh, the idol, are following after the fugitives in order to visit retribution upon them and regain their own. Albert tells how he gave the priests the slip in Hull. The Toff has brought them here to the old Inn which he has hired for a period of time. The sailors are restless; they see no more danger and desire to be off with their booty. When they tell this to the Toff he bids them take the ruby and go. They do so, but the next moment are back through the door. They have seen the Priests of Klesh who have followed all the way from Hull — eighty miles on foot. The Toff has expected this, and has acted in consequence. He tells them that they must kill the priests if they ever expect to enjoy the ruby in peace. Through his cleverness the priests are trapped one after the other, and are murdered. The four then celebrate their victory, but one goes out for a pail of water and comes back pale and shaking, disclaiming any part in the ruby. Klesh himself enters, blind and groping. He takes the ruby eye and placing it in his forehead goes out. Then a voice is heard calling one of the seamen. He does not want to go but is impelled by some mysterious force. He goes out, a single moan is heard, and it is over. The next seaman is called, and then the third. Last of all the Toff hears the command and makes his final exit.

ALBERT(going). Toffy, Toffy.(Exit.)

VOICE. Meestaire Jacob Smith, Able Seaman.

SNIGGERS. I can’t go, Toffy. I can’t go. I can’t do it. (He goes.)

VOICE. Meestaire Arnold Everett Scott-Fortescue, late Esquire, Able Seaman.

THE TOFF. I did not foresee it. (Exit.)

Curtain.

He did not foresee it, just as Agmar did not foresee the result of his impiety. Herein the two plays are close together, but “The Gods of the Mountain” is immeasurably superior both in conception, and in the handling of its theme. It has poetry, and characterization, whereas the second play is pure melodrama. And certainly it is one of the best melodramas ever written. The one error made in the entrance of the gods in the first play has been repeated here, and with just as detrimental an effect. The same arguments which we considered then apply now and with equal force. It cannot be done. The illusion is destroyed immediately. This is the only error to be found in either play, and it may be said again that it is an error not of the drama, but of the theater.

The construction of “A Night at an Inn” is really magnificent. Gradually it gathers force until it is in the full swing of tremendous action, and having reached the climax it pauses a single instant, and then with a marvelously quick reversal, it pitches down to the end. The “cloud no bigger than a man’s hand” is seen; it rapidly spreads over the whole situation, until finally it is dispelled to all appearances, but at the very moment of its disappearance it returns only to envelop the whole action. The play is extraordinary in its quick movement, its utter surety of purpose, and in the peripetia which gives it the power of its final blow. That is one of the most astonishing things about all these plays; they show a skill, and not only a facility, but a power of handling, which one is much more likely to ascribe to an old hand than to a man who does not make dramaturgy his sole business in life. Dunsany always knows exactly what he wants to do, and exactly how to do it. Under the circumstances this is surely rather astounding. There are more necessary mechanics connected with the drama than with any other form of the literary art. Neither the poem nor the novel has so rigid a structure (the short story may have), and it is therefore surprising to find so complete a control over a medium to which one has not devoted much time and energy. But this is implying that Lord Dunsany has written no other plays than those we know, and this indeed may be the case. We speak of a man’s first play, not taking into consideration the many plays he may have written and consigned to the waste-basket. It is often those plays which make a man a writer, just as it is the “scrub” team that makes the varsity what it is. But all evidence goes to prove that Dunsany’s first play was “The Glittering Gate”, written for Yeats, and followed by “King Argimenes and the Unknown Warrior.” Both these plays show the hand of the tyro in places, but they both indicate a grasp of form that is amazing. I fear that my use of the word “form” may be antagonistic to those restless spirits who chatter so easily of “freeing the drama from the shackles of dogma.” I have a strong inward conviction, however, that when they have rid themselves satisfactorily of the shackles, they will find that somewhere in the scuffle they have lost the drama. However — !

In their sudden reverse twist at the end, Dunsany’s plays remind one of O. Henry’s short stories. With both writers too the same sense of economy is evident. Not a word could be subtracted from “A Night at an Inn” without its loss being felt. Sometimes this is carried almost to an extreme. Dunsany’s imagination outruns his pen on occasion, and there is a paucity of stage “business” in his manuscripts that has made at least one producer gasp. In the plays one sometimes feels that while all the high lights are present there is a lack of shadowing, of detailed line work which, while not vital, is at least desirable. The plays are never in the least slovenly in workmanship, quite otherwise in fact, but there is present a sense that not enough time has been spent on them to give us all that the author has imagined. This doubtless arises from the fact that Dunsany concerns himself with nothing beyond the story itself. He is not interested in the lights and shadows of a more subtle characterization, and this is without doubt a serious weakness. But it is only in the acceptance of a work of art for what it is, without regrets for what it might have been, that we can arrive at any conclusion.

The resemblance of “A Night at an Inn” to “The Gods of the Mountain” is particularly interesting as showing how effectively the same theme can be treated in separate ways. The Toff parallels Agmar, the sailors are of the same ilk as the beggars, and the gods are always the same. The same philosophy is present in both plays, but the sublime audacity of the first raises it to heights of which the other is not capable. Moreover we are interested in Agmar as a personal problem, while in the Toff we never feel such interest. The beggars are individualized; the sailors are treated collectively. All this marks the difference between the two plays especially in that one is drama, and the other is melodrama in which the plot motivates the action, as opposed to drama in which the action is motivated by character. “A Night at an Inn” will always remain one of Dunsany’s most effective plays because it is so perfect of its kind, although that kind may not be of the highest type. Certainly it shows that Dunsany can provide plenty of action when action is called for. It is vital to the effect of the play that the action be extremely brief after the entrance of Klesh, yet there are still certain definite things to be accomplished. Without conveying a sense of undue hurry, with only such speed as is necessary to keep the pitch, the play is brought to its logical conclusion. There can be no question that, with the exception of the bringing of Klesh on the stage, the play stands the acid test in every particular. It is a thrilling bit of work; a tour de force which is reminiscent of the Grand Guignol, but which is wholly lacking in the morbidity that is so characteristic of that Chamber of Horrors.

The idea of dramatic contrast is very interestingly carried out in this play. To take a minor instance, observe how the quiet calm, the detached disinterestedness of the Toff stands out against the sailors with their quicker, easier emotions. In Agmar, and in the Toff, one fancies that the author is unconsciously drawing a picture of himself as he would be with the poet absent. There is a certain vague similarity in the mental attitudes of the three. To return to the contrast; it was surely a daring thing to set so grotesque a conception in so commonplace a background, an old English Inn. One would think that gods and half clothed priests would enter here only to be laughed at. It would seem to be like playing “Macbeth” in evening clothes. It is through sheer skill that the result actually achieved is quite otherwise. From the rise of the curtain the atmosphere is so definite and so tense that there is no possible thought of incongruity. One never has to “get into” the atmosphere of a Dunsany play. The atmosphere reaches out and holds you even against your will. This is due partly to the fact that Dunsany himself is convinced, and that therefore he is enabled to be convincing. He believes so thoroughly in his own creations, at least while he is working on them, that the audience cannot but feel the force of his belief. More than this it is skill in writing, and, mark you, it is the skill of the poet rather than that of the dramatist. A playwright is able to create an atmosphere of this description only when he is a poet also. The ability of Dunsany to do this and to do it well is one of his strongest assets, and “A Night at an Inn” is a perfect example of this phase.