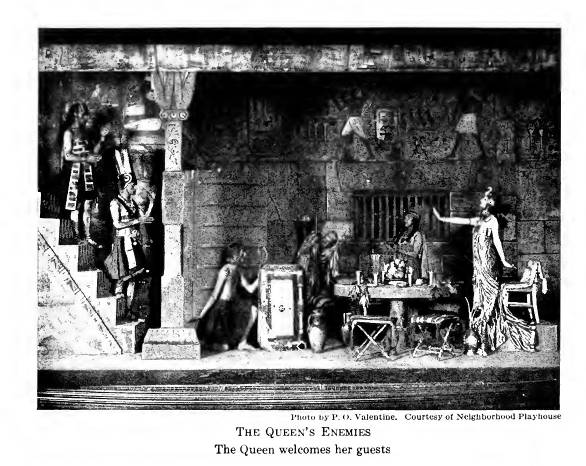

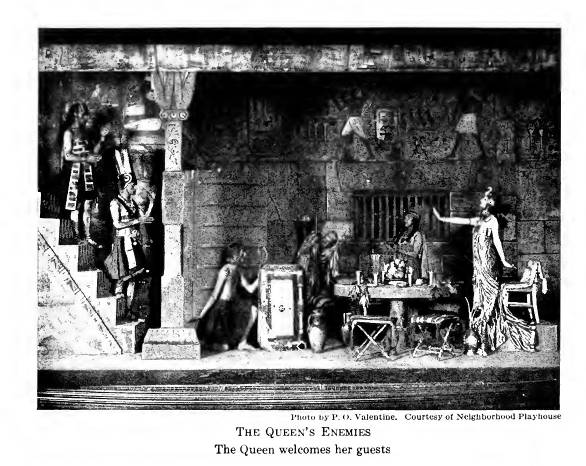

The place of this play is in the great room of an underground temple situated on the bank of the Nile; the time is that of an early dynasty. The stage is divided into two sections. On the right one may see a steep flight of stone steps leading down to a door which opens into the room itself. The stage is dark. Two slaves come down the steps with torches. They have been ordered to prepare the room for the Queen, who is about to feast there with her enemies.

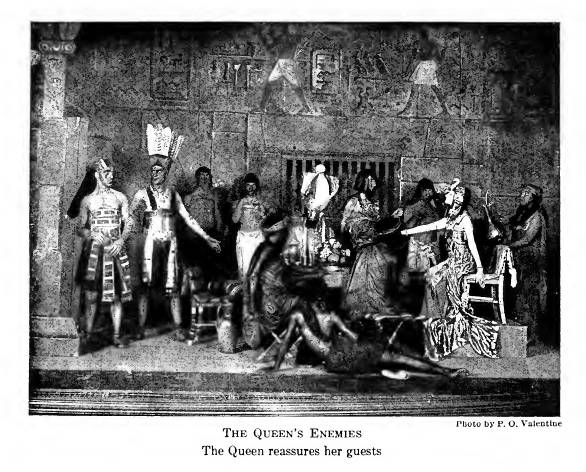

They look about the room of the old disused temple and comment upon the strange eccentricity of their mistress. A great table is set in the center and at one end of it has been placed a throne. From the shadow of the throne moves a huge figure, much to the terror of the slaves. It is Harlee, a servant of the Queen. He is dumb, his tongue having been pulled out by the roots. He laughs at the two, and moves to one side. The slaves go, and the Queen with her attendant comes down the long flight of steps into the room. The Queen is young, and slender, and pretty. She bemoans the fact that she has enemies. Her Captains have taken their lands but she knows naught of it. She is plaintive, beseeching, almost querulous as she asks, “Oh, why have I enemies?” Now she has planned this feast of reconciliation. But she is afraid to be there alone with her enemies. She is so small and young; they may kill her. After many doubts and complainings; after much fear and trembling she decided to go through with it. At the top of the steps leading to the closed door appear two of the invited Princes. One of them is distrustful and does not want to go further. He fears a trap. Finally he induces his fellow to turn back, but as they are about to do so the others arrive and there is nothing to do but to enter. The Princes, a King, and the High-Priest come with their slaves. The Queen greets them timidly. They stand about the room uncertain whether to trust her or not. The old dumb slave of the Queen is at her side, and she murmurs to him, “To your post, Harlee.” He goes, though one of the Princes stops him and inquires his mission — but he is dumb. The Queen finally manages to persuade her guests to sit at the feasting board. They fear to eat, and the Queen weeps that they should so distrust her. Moved by her tears they eat. She offers a toast to the future. As they are about to drink it the High-Priest says that a voice has just come to him speaking in his ear telling him not to drink to the future. His fears are laughed at and the toast is drunk. Then the company becomes merry, and jest and story fly across the board. The Queen joins in at first, but when she sees that her guests are occupied she slips from her throne and with her attendant tries to leave the room. She is stopped at once, for they are distrustful of her still. But she has promised to restore to them the lands she has taken, and they cannot believe that she would harm them. By her generosity she has made them all her friends. The Queen says that she must go to pray to a very secret god, and so she is permitted to depart. She goes out and part way up the steps, while the great door closes fast behind her. The guests try the door when she has gone. It is locked. They fear once more a trap. Slaves are posted at the door with weapons and they all wait in silence for what may come. The Queen above them, unseen and unheard by them, on the steps lifts her voice and prays to old Father Nile. She tells him that she has a sacrifice worthy of him — Princes, a King, and a Priest. She asks that he come and take them from her. She pauses, but there comes no answer. Then she calls swiftly, “Harlee, Harlee, let in the water!” There is another deathly pause. Then, as the lights darken, from an opening in the room below, the water from the Nile pours in, and amid cries and shrieks, the enemies of the Queen are drowned. The water rises up the steps from underneath the door; as it reaches the Queen she lifts her garment out of its way and then, mounting a step higher, she murmurs voluptuously, “Oh, I shall sleep to-night!” She slowly climbs the steps with her attendant and vanishes.

In the character of the Queen we are confronted with a problem which the play itself does little to solve. Is her act simply a cold blooded deliberate murder, or was it a sudden impulse? Throughout the play she maintains an attitude of injured virtue, and of entire innocence. This pose on her part is stressed until it is unmistakable. Is this hypocrisy or is it natural? If it is natural she could never have done what she did. The two things are wholly incongruous; if she is one she cannot seemingly be the other. One cannot be a sweet and innocent girl and a Lady Macbeth at the same time. On the other hand, if this attitude is merely a pose, why is this not made evident? To keep such a matter from the audience is fatal. There are any number of times when the Queen could have thrown off the mask, but she never did so. The result of all this has been to make the character of this royal lady extremely obscure. We all agree that it is a most interesting play, but what is the mystery of the Queen? She is not consistent; nor is she even consistently inconsistent. The fact that she told Harlee early in the action to go to his post, and then later called to him to let in the water surely indicates beyond question that the murder was most carefully planned and arranged for. The very fact of the feasting place, underground and on the bank of the Nile, suggests this also. But the character of the Queen as it is shown us does not suggest it in the slightest degree, and the sign-posts which I have just mentioned are too slight to afford adequate warning. Hence the Dunsanyesque surprise at the end of the play comes with an unexpected shock; the characterization so carefully built up is shattered in an instant, and we are left to gasp in amazement at what seems an utter incongruity. Surprise calls for careful preparation, and here there is little or none of it. In both “The Gods of the Mountain” and “A Night at an Inn” the sense of menace and foreboding is gradually built up until the event of which it gave warning has transpired. But in “The Queen’s Enemies” we are shown a woman who is one thing and who does another without warning or explanation. Our sense of the fitness of things is violated. It is bad dramaturgy somewhere.

It so happens that Lord Dunsany has himself furnished the key to the problem, and before discussing the play further I will submit his own explanation. The Queen is wholly unconscious of any wrong doing. She is an aesthete; anything ugly either in itself or in its effect upon her is to her a distinct immorality, something to be obliterated from the face of the earth, to suffer nothing but annihilation. Being this she is of course sublimely selfish. She is selfish too in the absolute, not the relative sense. If a dirty child brushed against her she would kill that child. And yet she is of the most delicate sensibility; these things hurt her, and she blots them out of existence not because she feels a satisfaction in the act — there is no sense of vengeance, or of malice — but because she believes it to be a divine duty to rid the earth of that which she deems a painful disfigurement. So when she prays to Father Nile to send the water she fully believes that in offering this sacrifice she is performing a holy task — albeit a most unpleasant one. But, being a woman, she does not rely too greatly on Father Nile, and has placed Harlee at the flood-gates, so that if the deity does not respond the sacrifice will still be accomplished. And afterward, when the water rises from the flooded room up the steps to the hem of her garment, knowing that those who were a menace to her, who haunted her bedside, driving slumber into the shadows, and who were to her the very apotheosis of all that is evil because they balked her will, were gone for ever, she revels in that which she has done, knowing that her offering to the gods will bring to her the rest and peace she desires. She is an æsthete wholly without a moral sense; which is to say, only a sensualist.

If this were all brought out in the play it would be very well, but it is not so brought out. Lord Dunsany has attempted a characterization which was beyond him considering his lack of entire acquaintance with his medium. I have pointed out several times before that he did not as a rule furnish that background so necessary to vitalize a character into a living personality, but never before has there been the same need for so doing. Now such a background is imperative, and the fact that it is not there has frustrated his design. The play is intended to be an immensely subtle characterization. Dunsany’s tendency to show only the high spots has reduced the subtlety to intelligibility in this instance. It was vital that the background should be filled in. The play is interesting, and has been successful because of its atmosphere, and of its action. But the motivating force of this action is entirely obscure. The play is like a book in which one sees only the chapter headings and the illustrations.

For several reasons I am inclined to suspect that Dunsany intended in this play to convey the idea that the Queen was in reality not at all different from the ordinary woman, indeed that she typified in this phase of her character Woman in the generic sense. The moral would be in that case that women are utterly ruthless in their pursuit of whatever they desire, and that anything which stands in the way of such a pursuit is to them merely an evil to be extinguished. This attitude on the part of Lord Dunsany toward woman in general I shall take up more in detail a little later, as it applies to several of the plays. As Miss Prism remarked to Dr. Chasuble in “The Importance of Being Earnest”, “A misanthrope I can understand — a womanthrope, never!” I think it is perfectly safe to acquit Lord Dunsany of being a “womanthrope”!

It has been suggested several times that the play would have been vastly improved if it had been a short story; that the drama was not the medium for this theme. To a certain extent this theory is tenable. The story writer can fill in a mass of detailed characterization in description which the dramatist must express in terms of action, a much more difficult task. Hence there are undoubtedly some themes which the playwright would do well to leave to his fellow craftsman. I do not believe, however, that this is one of them. I see no reason why the story of this unconsciously cruel Queen, for all her subtlety, should not be told in dramatic form. The best solution would probably be to give the play another act, making the present act the second. In act one all necessary background could be given quite easily and dramatically through some incident or episode which would suggest in itself all that has been omitted in the present version.

“The Queen’s Enemies” is one of Lord Dunsany’s poorest plays. And though this be true it has been successful and deservedly so. It tells an interesting story in a most dramatic manner; it has atmosphere and colour, and it shows amusingly how much better Dunsany is at his worst than many others at their best. I class the play as I do because it fails of the purpose for which it was intended. It set out to show something, and it failed to show it, and in the failing it obscured the action. The salient point of the play, its real raison d’etre, is the underlying motive which prompts the action, and this motive is so vague as to be incoherent. That which remains, the action itself, saves the piece, but it is not enough to turn the play into that which it would have been had the whole motivation been apparent. That such motivation was intended is very evident, and that the intention was not carried out is equally so.

As for the poetry of the play, that lies hidden for the most part with that portion which has never seen the light. It is not there; the most that we can say is that if the play had been written as it was intended, it would have been.

I may seem to have devoted an over-amount of space to the faults of “The Queen’s Enemies”, and to have been even captious in my criticism of it. The play which has few or no flaws, and is able to stand upon its own feet, naturally requires less attention than that play of which the reverse is true. If a thing is good, and if we like it, we do not have to have it explained to us. But to understand an evil is to forgive it — which applies here, bad paraphrase though it is.