THE following letters are taken from a correspondence between Mr. Stuart Walker, who has staged three of the Dunsany plays in his Portmanteau Theater, and Lord Dunsany. The letters throw light on not a little connected with the plays, in acting, staging, and in the philosophy underlying them. Lord Dunsany’s letters are given verbatim, and those of Mr. Walker have been relieved only of such matter as did not seem to have a direct bearing on the subject at hand. The letters speak for themselves, and require no further introduction or comment.

Excerpts from a letter from Lord Dunsany to Mrs.

Emma Garrett Boyd

Not dated.

... There are many others who know me and know my work, and a great many that know me and never heard of my work, and many others to whom my work is a harmless eccentricity or a chance occupation less important than golf.

... I was wounded less than three weeks ago. The bullet has been extracted and I am healing up rapidly. I am also under orders for France as soon as I have recovered.

... Sometimes I think that no man is taken hence until he has done the work that he is here to do, and, looking back on five battles and other escapes from death, this theory seems only plausible; but how can one hold it when one thinks of the deaths of Shelley and Keats!

But in case I shall not be able to explain my work, I think the first thing to tell them is that it does not need explanation. One does not explain a sunset nor does one need to explain a work of art. One may analyse, of course; that is profitable and interesting, but the growing demand to be told What It’s All About before one can even enjoy, is becoming absurd.

Don’t let them hunt for allegories. I may have written an allegory at some time, but if I have, it was a quite obvious one, and as a general rule, I have nothing to do with allegories.

What is an allegory? A man wants the streets to be better swept in his town, or he wants his neighbors to have rather cleaner morals. He can’t say so straight out, because he might be had up for libel, so he says what he has to say, but he says it about some extinct king in Babylon, but he’s thinking of his one horse town all the time. Now when I write of Babylon, there are people who can not see that I write of it for love of Babylon’s ways, and they think I’m thinking of London still and our beastly Parliament.

Only I get further east than Babylon, even to Kingdoms that seem to lie in the twilight beyond the East of the World. I want to write about men and women and the great forces that have been with them from their cradle up — forces that the centuries have neither aged nor weakened. Not about people who are so interested about the latest mascot or motor that not enough remains when the trivial is sifted from them.

I will say first that in my plays I tell very simple stories, — so simple that sometimes people of this complex age, being brought up in intricacies, even fail to understand them. Secondly, no man ever wrote a simple story yet, because he is bound to color it with his own experience. Take my “Gods of the Mountain.” Some beggars, being hard up, pretend to be gods. Then they get all that they want. But Destiny, Nemesis, the Gods, punish them by turning them into the very idols they desire to be.

First of all you have a simple tale told dramatically, and along that you have hung, without any deliberate intention of mine — so far as I know — a truth, not true to London only or to New York or to one municipal party but to the experience of man. That is the kind of way that man does get hit by destiny. But mind you, that is all unconscious, though inevitable. I am not trying to teach anybody anything. I merely set out to make a work of art out of a simple theme, and God knows we want works of art in this age of corrugated iron. How many people hold the error that Shakespeare was of the school room! Whereas he was of the playground, as all artists are.

Dunsany.

Stuart Walker to Lady Dunsany

June 6, 1916.

My dear Lady Dunsany:

A cable from Miss Wollersen two days ago had informed me of Lord Dunsany’s misfortune. I trust that he is fairly on the road to complete recovery; it seems a great tragedy that one with universal messages should be silenced by rebellions and wars.

I have read “The Tents of the Arabs.” It is beautifully poetic but its lack of action makes it unavailable for me now. I have several plays of the type in preparation and I have to be careful not to attempt too many wherein the only movement is of the mind and spirit. But should the play still be free at the end of next season I should like to consider it again.

Before closing my letter I want to tell you that the costume plates for “The Golden Doom” are very promising. Mr. Frank Zimmerer, the artist, is a most capable young man and he uses Lord Dunsany’s green with great effectiveness. I call it the Dunsany Green. How else could I designate it? — the Green gods, Klesh, the green sword in “King Argimenes”, the green lantern outside Skarui’s door!

With every good wish for Lord Dunsany’s complete and rapid recovery,

Stuart Walker.

Lord Dunsany to Stuart Walker

June 28, 1916.

Dear Mr. Walker:

I am still in Ireland as I am still recovering from my wound, though I am very nearly ready to go now. Had I not been wounded I should now be in the trenches. So I am answering your letter to Lady Dunsany. Hughes Massie, I am glad to hear, are arranging for you to have “The Gods of the Mountain.”.... Whenever I may be abroad or dead, Lady Dunsany will make all arrangements. “Argimenes” was the first play I ever wrote about my own country. “The Glittering Gate” I had already written, chiefly to please Yeats, but that play never interested me. “Argimenes” was the first play laid in the native land of my spirit, and of course it has a first play’s imperfections, the most visible of which is I fear a downward trend from a fine scene of the King and his bone to a mere rounding off and ceasing, instead of rising the whole way like “The Gods of the Mountain.” Indeed I think I wrote the whole play from a sudden fancy I had of a king in rags gnawing a bone, but that fancy may have come from an inner memory of a time when I too was hungry, sitting and sleeping upon the ground with other dishevelled men in Africa.

The last stage direction in this play (in a voice of protest) was suggested to me by a producer and pleased me at the time but I almost think my own idea was better. I made Zarb say “Majesty” in awe. That he should throw away good bones reveals to Zarb, as nothing else has done, the pinnacle to which Argimenes has really risen. The other way is funny, but I think I ought to have stuck to my own inspiration. I amuse myself sometimes by cutting seals on silver and on the chance that it may amuse you if it arrives unbroken I will put one of them or more on this envelope.

Though the world may be growing more barbarous in Flanders, what you tell me of your aspirations shows that elsewhere it is becoming more civilized. As a matter of fact it is not the ruins of Ypres or a street in Dublin that shows the high water mark of our times’ barbarity; it is to be seen in London in our “musical.”

“comedies”, in much of our architecture, and in toys made for children.

Yours sincerely, Dunsany.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

July 12, 1916.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

When my mail was brought to me this morning the first thing that caught my eye was a light green seal which represented a god of the mountain. Before I turned to the face of the envelope I called my mother and my cousin to tell them that I need search no further for the design for the costumes. Then one of them asked who made the seals. The moment I turned the envelope I recognized your writing, which I had seen in the manuscript of “The Queen’s Enemies.”

Your letter pleased me very much, but shortly after I had read it, I heard that the rights to “A Night at an Inn” had gone definitely to Mr. Harrison Gray Fiske. Of course I was deeply disappointed for the addition of this play to my repertory would have meant a great deal to me. Mr. Fiske is much older in the theatre than I am, but I am hoping to make you very proud of my work on your other plays. I cabled to you to-day about “Argimenes” with more assurance than I have had for some time. Your suggestion that Zarb’s final “Majesty” is spoken in awe shows me that I shall be able to stage your work as you would like it. I have always, in reading the play aloud, read the word in awe. The direction “in a voice of protest” was, frankly, a shock to me because it changed Zarb and weakened the remarkable climax of the play, which by the way, I think builds very well in interest with sure dramatic strides — not as inevitably as “The Gods of the Mountain”, but beautifully, nevertheless.

I am going to tell you a few of my ideas about play-producing because I feel at ease after reading your statements about our uncivilized musical comedies and our absurd toys, for children. To my mind the play is the most important consideration. The ‘author must know what he is talking about and why he says what he does in the way he says it. There is a story to tell and I try to tell it in the author’s way. I don’t like symbolism as such, and I make no effort to foist upon an audience a suggestion that there is always some deep hidden meaning. There is a story to tell and that story must always have a certain effect upon the audience, and that effect is gained primarily through the actor’s ability to translate the author’s meaning into mental and physical action. The scenery must never be obtrusive; it is not and cannot be an end in itself; but to me lights come next to the actor in importance. With lights of various color and intensity, vast changes in space, and time, and thought can be suggested. My lighting system is very remarkable. Oh, how I wish you might see the beggars turn to stone.

I know your feeling for your first beloved play “King Argimenes” and I shall treat it with a fine affection. It seems almost wicked to discuss terms about beautiful things, about poetry; but I want you to know I am eager to help your name to its rightful place in America, and to try to see that your business treatment is just. I think “King Argimenes” will be especially successful in the spring and summer and in California when we play in the open air.

Stuart Walker.

Lord Dunsany to Stuart Walker

Brae Head House, Londonderry.

July 14, 1916.

Dear Mr. Walker:

I’ve just cabled accepting the terms of your cable received this morning. I hope you will like the play and that you will find it a success. You will probably not have the difficulties that I found in Dublin when “Argimenes” was acted. I found that the actors “off” who had the rather impressive chant of “Illuriel is fallen” to do, not being in sight of the audience would never trouble to do it accurately. There are two such chants, a mournful one and a joyous one, and they used to mix them up a good deal.

But then they used not to rehearse properly there.

I wish that print could convey the tone of voice in which things should be said, but it can’t.

Yours sincerely, Dunsany.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

July 17, 1916.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

The possession of “The Gods of the Mountain” and “The Golden Doom” makes me very happy. Now I am waiting word on “King Argimenes” with great hopes. It is a big play, but I am not expecting any such popular success for it, or for “The Golden Doom”, as “A Night at an Inn” will have or “The Gods of the Mountain” ought to have.

The loss of “A Night at an Inn” was a great disappointment to me. I saw it the first night at the Neighborhood Playhouse and I told the Misses Lewisohn then that I would do anything to get it. In my eagerness to get in touch with you I am afraid that I hurt or displeased them: but the process of reaching you seemed so terribly slow. I had already told them that I should defer to them even if I succeeded in reaching you first and that if I got the play I should let them use it at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Mr. Fiske ought to make a great popular success of his production. The play is quite the best short melodrama I have ever seen, but to my heart and mind, “The Golden Doom”, “The Gods of the Mountain”, and “King Argimenes” are far greater plays. “The Queen’s Enemies” is most interesting, but its mechanical requirements are difficult of achievement for the present. “The Tents of the Arabs” impressed me very much. I hope that I may try it sometimes when my resources are greater.

With every good wish, Stuart Walker.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

July 24.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

Mr. Zimmerer brought the scene designs for both “The Golden Doom” and “The Gods of the Mountain” last night, and I set them up in the model of my theatre to test them under the lights. “The Golden Doom” is really a remarkable setting. There are the great iron doors in the centre at the back of the stage. At each side of the doorway is a tall green column, with a black basalt base three feet high, standing on a basalt circle in a gray flooring. Hanging between the columns just below the flies is a large winged device in dark blue with a touch of orange here and there. Extending from the gates diagonally to the sides of the proscenium are very high black marble walls with a narrow dull-colored enameled brick “baseboard.” The only vivid colorings on the stage except the costumes are the green columns and an orange design on the iron doors. As in the winged device, Mr. Zimmerer has followed Assyrian and Babylonian designs closely in the cut and color of the costumes.

As the Portmanteau Theatre main stage is rather small, and the forestage is much used for the action of the plays, there were some difficult problems in the settings of “The Gods of the Mountain.” In the first act Mr. Zimmerer uses a small section of the wall between two bastions. It is built rather fantastically of colored rocks, and above it one can see the copper domes of Kongros, and in the distance the emerald peak of Marma. This last detail is interesting but I am not yet sure that it is best to have the mountain seen far beyond the city in the first act because I want to get an effect in the second and third acts. The Metropolitan Hall of Kongros is quite simple. The principal detail is a broad lunetteshaped window through which Marma is visible and it is with the play of lights upon Marma that I want to gain some impressive effects. In the costumes as in the wall of the first act Mr. Zimmerer uses oriental themes with no attempt at accuracy.

Kongros was in its heyday we believe some time after the fall of Illuriel and as we place it, it stood somewhere west of the Hills of Ting, but not so far southwest as ancient Ithara.

All our good wishes go to you, my dear Lord Dunsany.

S. W.

Lord Dunsany to Stuart Walker Londonderry, Ireland.

August 7, 1916.

My dear Mr. Walker:

Another welcome letter from you reminds me that I have not answered your last. I was waiting for a mood which should be worthy of the occasion, but I have had few moods but lazy ones ever since I was wounded.

I have always heard works of art spoken of as valueless or of value, usually the former, and on the rare occasions when they have been admitted to be of value I had found that they take their place with cheese. They are in fact a commodity or “article”, and have a price, and are valued according to it. It is therefore a great delight to find that you look on a work of art as a work of art. I had almost forgotten that it was one. I am sorry about “A Night at an Inn.” But as you say, it cannot touch the little “Golden Doom”, while to compare “The Gods of the Mountain” to it would be like comparing a man to his own shadow. Talking of “The Golden Doom”, there is one sentence in Björkman’s preface which particularly delighted me and that is the one in which he says that I show a child’s desire for a new toy and the fate of an empire as being of equal importance in the scheme of things. That is exactly what I intended, the unforeseen effect of the very little — not that I am trying to teach anybody anything of course, I may mention white chalk while I am telling a story if I have happened to notice that chalk is white, but without any intention of thrusting a message into the ears, or a lesson on whiteness: people seem to have been so much frightened by the school-master when they were young that they think they see him in everyone ever after.

Often critics see in my plays things that I did not know were there. And that is as it should be, for instinct is swift and unconscious, while reason is plodding and slow, and comes up long afterward and explains things, but instinct does not stop for explanations. An artist’s “message” is from instinct to sympathy. I try sometimes to explain genius to people who mistrust or hate it by telling them it is doing anything, as a fish swims or a swallow flies, perfectly, simply and with absolute ease. Genius is in fact an infinite capacity for not taking pains.

August 8.

It has just occurred to me that perhaps you never got my cable in answer to your letter about “Argimenes.” I cabled “Right” meaning that I accepted your terms; but the Censor, who is wiser than I, found in this message a menace to the stability of the Realm, and an explanation of my invidious cable was demanded. This I supplied, and thought the cable had gone, but it may have been considered too dangerous in the end. What tended to annoy me about this delay was, that even if my cable had been an invitation through you to Hindenburg to land an army corps on the Irish coast, I am one of the people who would have to assist to push it off again, and as my name, rank, and regiment had to be signed in the cable form this thought might have occurred to others. Perhaps you got my cable after all, though delayed, but in any case it’s no use grumbling.

About “The Golden Doom.” The Haymarket Theatre acquired the rights for five years in November, 1912, but in any country in which they neglected to perform it they lost the rights after three years, and they returned to me. This applies to the U. S. A.; the rights returned to me last winter, but in any case they do not belong to the printer or binder of “Five Plays,” What is more important is that the larger the children are the more they might be apt to blur the point of the play which is, that though they are clearly seen, they are overlooked and ignored. If the girl child appeared say 14 the sentries would probably be looking at her, if she was 15 they would never take their eyes off her the whole time, if they were the kind of sentries I have met — and they probably were in Zericon at the time Babylon fell. The audience would probably feel this. But to go on talking about important matters like war to a soldier, while small children are playing in the dirt or sand, is humanly natural.

I thought I noticed this at the Haymarket, when they started with small children but altered the cast afterward and changed the size. But of course it is only a matter of illusion.

The “public” must needs know exactly “when it all happened” so I never neglect to inform them of the time. Since man does not alter it does not in the least matter what time I put, unless I am writing a play about his clothes or his motor car, so I put “about the time of the fall of Babylon”, it seemed a nice breezy time, but “about the time of the invention of Carter’s Pills” would of course do equally well. Well, the result was that they went to the British Museum and got the exact costumes of the period in Babylon, and it did very nicely. There are sure to have been people who said, “Now my children you shall come to the theatre and enjoy yourselves, but at the same time you shall learn what it was really like in Babylon.” The fact is the schoolmaster has got loose, and he must be caged, so that people can enjoy themselves without being pounced on and made to lead better lives, like African natives being carried away by lions while they danced.

Military duties have somewhat interfered with the course of this letter and the taking of a wasps’ nest to amuse some children that live near here, and my own small boy, may interfere with it further.

I meant when I got your last letter to write to you sometime and send you a few comments on “Argimenes”, for print unfortunately cannot convey the tone in which words are said, and often in the tone is the meaning. I have “Argimenes” by me now and probably shan’t find much to say about it. First of all on page 63 (American edition). Zarb in his utterance of the word Majesty shows that he attaches more importance to the empty glory of being called Majesty than to the possession of a horse or any other advantage he enumerates. But after all this sort of detail is too trivial to be of any interest and you will have noticed already how Argimenes with his wider views and knowledge of strategy appears witless to Zarb when it comes to the detail of the daily life of a soldier of the slave guard. Probably if we were suddenly made to live amongst insects it would come out that we knew nothing about the smell of grass or even its exact color, and the insects would wonder how any creature living in the world could be so ignorant of a thing so common as grass.

Another little note. Page 75. An old slave—” Will Argimenes give me a sword?” He says it as one who sees a dream too glorious to be true.

Old Slave— “A sword!” He says it as one the dream of whose life has come true. “No, no, I must not.” He says it as one who sees it was only a dream. But in the book this change between sword and no is not indicated. Of course I always liked to read my play aloud before it was acted to show the actors what my ideas were, which print often fails to do.

Aug. 9.

I have just received yours of July 19th this morning, and see by it that you never received the cable that I sent and for which I paid. Do not think badly of our Censor, but reflect that God for his own good reasons has given wisdom to some, while upon others for reasons as divinely wise he has showered stupidity. I have no redress.

Yours very sincerely, Dunsany.

Lord Dunsany to Stuart Walker

Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry, Ireland.

My dear Mr. Walker, —

My last letter to you ended somewhat abruptly, my mind being too preoccupied with the stupidity of the Censor who seems to have stopped my cable to you in which I accepted your terms for my two act play on July 14th. I write to say how the pictures of the plays you have done delight me. You evidently have the spirit of Fairyland there.

August 13.

I am glad you like the seal of the god among the mountains. I cut seals on silver whenever leisure and an idea fall in the same hour, and this one is almost my favorite.

I was looking the other day at a photograph that Miss Lewisohn sent me of “A Night at an Inn” and I was much struck with the print of a spaniel with a duck in his mouth hanging on the wall; such a hackneyed homely touch as that must have made a splendid background for Klesh when he came in so faithfully following the stage directions, which are that “he was a long sight uglier than anything else in the world.”

Let me hear how you are getting on with “Argimenes” and “The Golden Doom.” I don’t get many letters from America and as it seems to be the most fertile soil upon which my work has fallen I should be glad to hear oftener from there. I don’t suppose my brother officers know that I write, and all European soils are so harrowed by war that nothing grows there but death.

August 15.

I have just received your letters dated July 24th and 26th.

I am glad to hear that you have after all received the cable I sent off on July 14th.

Mr. Zimmerer’s designs sound magnificent. Your words ‘with no attempt at accuracy’ please me, they are like a window open in a heated schoolroom; for this age has become a schoolroom, and nasty, exact, little facts hem us round, leaving no room for wonder.

You have placed Kongros exactly; all maps agree with you; for though they do not actually mark it, the tracks across the desert — taken in conjunction with the passage over the hills of Ting — and regarded in the light of all travellers’ tales — can only-point to one thing. It is there, as you have said, that one will find Kongros. Yet one counsel and a warning the traveller should take to his heart, let him heap scorn upon himself in the Gate, let him speak meanly of himself and vilify his origin, for they tell a fable to-day, even in Kongros Gate (the old men tell it seated in the dust) of how there once came folk to Kongros City that made themselves out to be greater than men may be. What happened to them who can say? For it was long ago. Without doubt the green gods seated in the city are the true gods, worn by time though they be; and above all let the traveller abase himself before the beggars there, and humble himself before them; for who may say what they are or whence they come?

Regarding “The Golden Doom”, a critic said in London that it was death to touch the iron door and yet a lot of people touched it. There might be something in that but not much I think. The children of course are ignored — the play hinges on that — and after all someone must open the door for the King, and his retinue accompanies him, but better not let any unauthorized person touch it unnecessarily, for it would be a pity to kill a good actor just for the sake of realism.

Even as I went out of my quarters, five minutes ago, after writing this, I saw eight squads drilling on the parade ground and two children right in the middle trying to dig with sticks and no one saying a word to them, so I know that my “Golden Doom” is true to life. But after all it is easy to be true to life when one writes of man and the dreams of man, and not of some particular set of fashions in dress or catchwords that may be regarded as being untrue to all time.

Yours very sincerely, Dunsany.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

October 2, 1916.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

Your letters of mid-August were forwarded to me at Wyoming. They had been despoiled of their seals but no black pencil or heedless shears had laid the contents waste. I have a very serious quarrel, because I am quite sure one of my letters and several bits of printed matter never reached you. Many months ago I sent my message to you whose work has said so much to me, and I told you then what I thought of “The Golden Doom” and what I hoped for “The Gods of the Mountain”, and “King Argimenes.” America did not know you so well then. Now I take pride in telling you that even the salesmen in the bookshops know your name, the names of your books — even those reported out of print — and have their individual way of pronouncing everything. Many of them have friends who know you, and these friends come back like travellers past Marma with their wonder tales and pronunciations. You are variously called Dun’ sany, Doon sah ny, Dun sa ny, Dun san y, author of Ar gim i nez, Ar gi mee neez, Argi me nez, I myself have chosen the pronunciation of Argimenes — the ar as in are, the gi as in give, s as z — There! the eternal pedagogue is showing beneath my youth, I fear; but I call Argimenes what I do call him because I think he would like it, even though he had another way.

We had our public dress rehearsals of “The Golden Doom” and “The Gods of the Mountain” at Wyoming. And here is where I should like to tell you what these curtains opening on the realization of my dream meant to me; but I cannot. I have not your words to picture intangible things. I can tell you only that I was very happy to see in my own little theatre what I know to be a great work. “The Golden Doom” was remarkable and its effect upon the audience was indescribable. The scene you know. Under the lights it was impressive. But now that you have told me what you think of schoolrooms may I confess that Mr. Zimmerer did use Assyrian and Babylonian designs but with less attempt at accuracy than I led you to believe. The Sentries were very good. I had already made them very human sentries before your letter came, not because I have known raw man through time and space, as you have, but because I have known him from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes and from a Louisiana hamlet to New York. The children are young. They are played without strain by charming people who give the illusion of innocence and wonder. The King and his Chamberlain are impressive and the Prophets with their cloaks are joys. When they make the sign to the stars — laying the backs of their right hands horizontally against their foreheads they disclose a great flat jewel in the palm of the hand. The spies, who are usually played as jumping jacks, are very skillfully played in all seriousness. Comedy is so near the surface of life that it can find its way without the forcing tried by most directors. And “The Golden Doom” is life to me. I introduce music twice. When the King orders a sacrifice to be made, an attendant bears the order to the nearest temple and presently a stringed instrument strangely played (a bronze gong and a torn-torn mark the rhythm) is heard. After the order is rescinded the musician plucks a dirge faintly, for have the priests not donned their black cloaks? The audience was deeply impressed. But I have always known it was a great play.

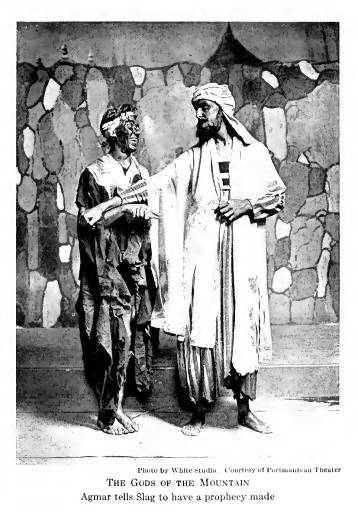

I cannot write so surely of “The Gods of the Mountain” because I am playing Agmar and my judgment is that of the actor who feels the audience during the play and hears the verdict afterward. Evidently however the audience understood you. They laughed at the right time, and what is better still, they shuddered at the right time and cheered when the final curtains closed. I have taken two liberties in the first act. Will you send your approval quickly? The curtains open after a moment of music that tells of the East. The mottled wall, the copper domes of Kongros, and green Marma piercing the sky in the distance, are visible in the bright sunlight. Ulf, penurious and suspicious, Oogno, the gluttonous and care free, and Thahn, the inefficient and wheezy, are seated under the wall. An old water bearer passes by, then a dromedary man. A moment later a fat woman singing a song which the successful beggars imitate goes into the city but offers no alms. A snake-charmer passes — oh, but her dress is a marvel of white and orange and red — she drops one of her snakes into fat Oogno’s bowl. Agmar followed by his one eyed retainer enters; Agmar in purple rags, and the other in black that has been fastened together at strategical points by pink which he must have stolen in Ackara. I have Mian brought on the first act. He is little, inefficient, young, and speechless, but he makes the seventh beggar. The end of the first act shows the seven beggars. They put the green raiment underneath their rags. Agmar lines them up, looks them over, shows them the attitude of the gods once more and takes his place at the head of the column. The curtains close as the beggars disappear into the city.... Of course I have not added any lines, but the business holds very well.

In the second act I have made the character whose child is bitten by a death adder a mother. I think the scene gains in pathos and prepares somewhat more effectively for the third act which is tremendous. I have had the thrones made so that they are palpably imitation and this seems to add to the impressiveness of the final picture, when the fearful citizens have slunk away leaving the seven stone beggars to themselves: in the distance green Marma pierces a blue night sky.... Mr. Arthur Farwell, one of our best American composers, has done the music for “The Gods of the Mountain” and his grasp of your story is excellent.

We have not yet put “King Argimenes” into the scene, but it is going very well in rehearsal. Mr. Harry Gilbert is writing the music for this, and the tear song and the wine song are promising. I think in fact that you would be highly pleased with what we are doing.

Our season opens Oct. 23rd at Springfield, Massachusetts, and for five weeks we play in the East in the larger cities — on November 27th we open in New York at the 39th Street Theatre which is really well arranged for your performances. Our opening bill will in all likelihood consist of “The Golden Doom”, “Nevertheless”, “The Flame Man”, and my own “Six Who Pass While the Lentils Boil.” On Thursday and Saturday mornings of the first week we shall play for children — and what an audience they will make! I use a prologue for some of my own plays and with your permission I am going to make him speak some of your lines before “The Golden Doom.” Of course I shall submit the lines to you for approval. I want to open the performance in New York with a prologue to the Theatre, a copy of which I enclose. Then the Prologue of the plays will speak a few words: if no news spreader were listening I should call them mood words. These prologues were liked last season very much. Such lines as your “Come with me, ladies and gentlemen who are in any wise weary of London (may I substitute the City for London?) come with me: and those that tire at all of the world we know; for we have new worlds here.”

Haven’t you some new plays that I can see?

With every good wish —

Stuart Walker.

Lord Dunsany to Stuart Walker

Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry, Ireland.

Oct. 26.

My dear Mr. Walker:

I have looked forward for a long time to hearing from you again and was delighted this morning to find your letter of Oct. 2. It is delightful to find somebody just going ahead with my play without asking if it is What The Public Wants (as though the Public had irrevocably decided just what it wants forever), if the audience will understand it, — and generally muddling round.

Well, to answer your letter bit by bit, first of all the one way that nobody should pronounce my name is the way people do who call it Dun’ sa ny, for pretty as the dactyl is it is not a dactyl. Those who call it Doon-sahny have every right to do so, for since it is the name of an Irish place one can hardly blame people for pronouncing it in an old Irish unanglicized manner. I don’t know, about the Sahny, but Doon is I believe a quite correct pronunciation of those circular things which in Ireland are usually spelt dun and which appear in London as don, from one of which my name evidently had its name. But as a matter of fact I pronounce it Dun sa ny, with the accent on the second syllable which is pronounced as say, the first syllable rhyming with gun. To come to a much more important matter you are right about Argi meen eez, the principle accent falling on the 3rd syllable, the g is hard, the gi as in give, and the whole arrangement of the word as in Artaxerxes.

The Censor will wonder who Argimenes (to spell him correctly) is, and why the hell it should matter how my name is pronounced in America.

No, it is impossible to substitute “the city” for “London” in my preface to “The Book of Wonder.” It would upset the rhythm and make a sentence that I could never have written. Say “who are in any wise weary of cities” and you will be all right. Use the phrase as much as you like. Wall Street, if applicable, would sound splendid.

What you tell me of the way you are doing my plays makes me feel sure they will succeed, not only because of the way you are doing them, but because your letter makes me confident that their fortunes can safely be intrusted to you. —

I wish I could read each play to you once, for neither pen nor typist can say exactly where the stress is to fall, in spite of them the rhythm can be missed, and even in some cases they may not show clearly with what motive little words are said, while some appear to have significance where none is intended.

I wonder how the sentry will say “I would that I were swimming down the Gyshon, on the cool side, under the fruit trees.” Sometimes my love of poetry overcomes the dramatist in me, and here and there are lines that I would like to hear said merely lyrically. If it be not blasphemous to mention his name while speaking of my own work I would say that Shakespeare had this fault: you read some such direction as, enter Two Murderers, and then you read some pure ecstasy of verse as the ruffians come on talking perhaps about dawn in fairyland.

I should like the sentry who has that line of mine to say the words “on the cool side, under the fruit trees” just as the last part of a hexameter. After all the — poets are right, there is a meaning in rhythm though it lie too deep and is too subtle for us to reason out, or perhaps it lies like joy clear all over the surface of the world, and so is missed by ‘ our logic that goes burrowing blind like the mole, over whose head the buttercups blow unseen: that is the right explanation, not my first; nothing lies too deep that is essential to life, or who would live?

I turn to your letter again. A gong and a tomtom are a lovely idea, and a flat jewel in the palm of the hand! Of course that is just the place where people would wear large flat jewels who had never known manual labor and whose only business was to bless. You say I know the scenes; but I wish I did. I never saw a design of it although you described it to me.

So you are Agmar. That is good.

The water-bearer and the snake-charmer and all will be great additions. Instead of citizens, etc at the foot of the programme you might write “One who sells water, A charmer of snakes”, and so on. Instantly the audience will know that they are before the gates of a country where water has its price, and the charming of snakes is an occupation.

Do what you like with Ulf. To me he appeared a man who in the course of his years had learned something of what is due to the gods: it is he, and he alone, that hints at Nemesis, and at the last he openly proclaims it—” (my fear) shall go from me crying like a dog from out a doomed city.”

A play writes itself out of one’s experience of life, going back even further than one can remember, and even, I think, into inherited memories. Our slow perceptions and toilsome reasoning can never keep pace with any work of art, and if I could tell you for certain the exact source and message of “The Gods of the Mountain” I could tell you also from what storms and out of what countries came every drop of the spring that is laughing out of the hill.

Therefore I only suggest that Ulf plays as it were the part of a train bearer to the shadow of some messenger from the gods. —

Oct. 26.

This letter has been lying about for some time so I had better send it off though your letter is but half answered.

Do send me photographs or designs of scenes, as many as you can, and Lady Dunsany would very-much like to have the music for the piano. Thus I shall be able to hear it, or at least an echo of it; she would also very much like to see the photographs.

I do not expect to go to the front before the middle of December.

I wish you the best of luck with your own plays and for your venture with mine. You are one of the prophets of my gods. In all history I know of no tale of a god without any prophet; that would be too sad even for history. May my gods protect you from the following, who stoned the prophets so often of old time and stone them still — they sweat and pant, for they have stoned for so many centuries, their hands are cut by the lifting of many flints, still they stone on, lest ever the prophets should live, they deem it a holy duty: —

Ignorance Apathy Empty Frivolity Fashion and many another begotten by the third upon the fourth. And so farewell.

Dunsany.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

November 5, 1916.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

My intention was to write you immediately after the first performance of “The Golden Doom” and “The Gods of the Mountain” but when I tell you that we have played 65 plays in 12 cities during the past two weeks you may understand my delay.

“The Golden Doom” was first performed on Tuesday Oct. 24th in Hartford Conn, and we have given five performances of it in the two weeks. It has made a very deep impression both with newspaper men and the public at large. When I have a moment to sit down and sort out my papers I shall send you some clippings. In one you will notice that the writer appreciates the youngness of the children. I do not generally approve of having a girl play a boy’s part, but Miss Rogers creates a most happy illusion, and this saves me from using my very remarkable Gregory Kelly in the part. He is somewhat too tall. I am more in love with your beautiful play than ever and it is to be used in the opening bill in New York City on Nov. 27th. Unfortunately, there are no photographs yet, because we have been moving about so feverishly and rapidly, that we cannot take time to set up a play especially for the photographer.

“The Gods of the Mountain” had its first performance at Mount Holyoke, and it is a great play. I shall send you photographs of myself as Agmar, and Mr. Kelly as Slag and several of the beggars. In playing Agmar, I have made him a man who would have been a great man if he had just been one step further advanced in understanding. Several of my friends have disagreed with me in not making him a physically powerful man. I am quite tall, being six feet and quite slender, and as you will see from the costume, I accentuate both the height and the slenderness of the man, and there are moments when I allow him to develop a real light in his eye, that is, the light that could shine through the ages if it were allowed to shine.

I am quite gratified that every notice has spoken of the final effect in the play when the seven beggars have turned to green stone and in the distance green Marma cleaves a deep blue sky. Enthusiasm at the end of this scene has been uniformly gratifying.

“King Argimenes” is to have its first performance next Friday November the 10th in Pittsburg.

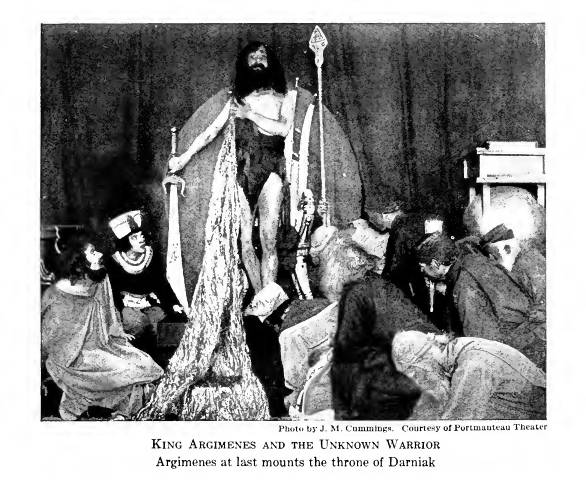

On account of the small size of the Portmanteau stage I have had a very difficult problem in the first act of suggesting great space, and finally succeeded in obtaining the desired effect I think. Instead of using your suggestion — the flat Darniak Slave Fields — I have used the side of a hill which Darniak mentions in the second act. All that the audience sees is the grass covered slope of the hill and into this has been cut a deep impressive trench, and in this trench are Argimenes and Zarb. The whole act is dull in color and depressive. In the second act, however, Mr. Zimmerer indulged himself in the most vivid colorings that we have on the Portmanteau stage. The entire stage is draped in black curtains. On a black dais is placed the Throne of Darniak. This throne seat is built out of elephant tusks. The back ones are seven feet high curving high over Darniak’s head, and the ivory is inlaid in places with vermilion and blue jewels. The seat of the throne is a vermilion cushion and immediately back of the throne is a great green circle, and running down the steps is a broad green crape which is laid on a black floor. To the right sits Illuriel. He is a marvelous creation in ivory, gold and vermilion, and he sits with oriental calmness on an agate column. On the other side of the throne stands an hour glass through which vermilion sand is slowly running, and this stands on top of a gold globe which in turn rests upon a vermilion standard. Darniak himself wears a black robe and seated on the steps at his feet is dark haired Atharlia in orange and red. The blonde Oxara is in lavender and white and silver. The feline Cahafra is in light blue and white and her hair is red. The tragic Thragolind is in gray and blue. I think you would like the Queens.

Just one more suggestion about “The Gods of the Mountain.” In the third act I have had the thrones built so that they are palpably imitative. Am I right in doing this? The altar in the second act is a great block of agate standing on ivory legs. It is really a wonderful piece of stage furniture.

Very truly yours, Stuart Walker.

Stuart Walker to Lord Dunsany

December 24, 1916.

My dear Lord Dunsany:

First let me thank you for the photograph which your uncle delivered to me. It is the pleasantest sort of assurance that the strange man shown in the article in the Boston Transcript was not you.

Our season in New York has proved more successful than I had hoped and we are now advertising our sixth week. It is unfortunate that we cannot stay longer because just the people to whom we want to appeal are finding us and sending their friends to see us. This resulted in good houses last week which is notoriously the worst week in the theatrical year. “King Argimenes” made a deep impression and so with “Gammer Gurton” and my own anonymous dramatization of “The Birthday of the Infanta” it will remain in the bill all the week. The critics have for once united in praise of my theatre and in the color and form of “King Argimenes” they forgot to say that the theatre is small.

“The Gods of the Mountain” has probably had its last performance here for this season because I think I see my way clear to produce it on a large scale next season. We have already played it in New York 16 times — a very fine record for a repertory company. We have played “The Golden Doom” 11 times. Of course when we return next season we shall repeat them. They are plays that I want to keep in my repertory for years and years to come, for despite the statement of the Sun critic that they are little plays, and the Mail man that you do not care much about the theatre or what becomes of your plays — he says you dabble in them as amateur poets dabble with the magazines — I am inclined to the certainty that your three plays will live as long as I live in the theatre, and ages beyond that.

“King Argimenes” strangely enough builds beautifully from the scene between Argimenes and Zarb to the finale of the second act when Argimenes decked in a robe of cloth of gold, mounts to the step of the throne and turns majestically before the ivory throne to order the burial of the late king. There has never been a suggestion of loss of tension in the second act. Not even during the scene of the queens and the prophet does the audience forget the crouching Argimenes who stole from the dark trench in the preceding act to kill the guard. After the queens leave the stage in the second act, I have the scene darkened to suggest a lapse of time. Then in a half light broken now and then by a gleam of torches, the rest of the play is done. When Darniak rushes in from the chamber of banquets to see Illuriel cast down I have the queens follow him and it is their voices that first take up the wail “Illuriel is fallen.” Besides their long-robed figures stealing in terror from the throne room are much more impressive than men’s figures would be in the half light.

Both Mr. Zimmerer and Mr. Farwell are very slow with their work for you. If I were to send you the score of the music as it is written for the harp, violin, and cello, I wonder if Lady Dunsany could use it? The photographs will suggest the scenes to you, but I am eager to have you see the color. I wish I could bring my whole model to you. Perhaps I shall be able to do so some day within the days of my youth. With every good wish for the New Year and new years, Stuart Walker.

Fragment of a letter from Lord Dunsany You ask me about my interpretation of “The Queen’s Enemies.” Well, it is the only play of mine yet acted in which the entire theme did not arise in my own mind; usually the whole country of the play with its kings and queens and customs arises there too. But the theme of “The Queen’s Enemies” I owe to a lady, and not one of those dreamy women who, having got an idea, write a sonnet about it or a play: she did it; she got the motive of drowning her enemies, so she invited them to dinner and drowned them. That is all I know about her.

It was not only easier but more amusing to imagine her character and all the names of her enemies than to be bothered with reading about her. And, since she was a live woman, whenever the Sixth Dynasty was thriving in Egypt, I think she came a little more alive out of my fancy than she might have done out of some dusty book. I mention this lady in order to show that the story is not only a very simple one, but so simple that it actually worked, and worked, I believe, very nicely.

If there is a moral in the play, I trust that neither you nor any other lady who has had anything to do with the play will “profit by” the moral, for I do not consider it at all right to give a dinner party and then drown your guests.

The Queen of my play was, of course, an unusual character, but it is not entirely unique. She is self-centered. Enemies annoy her. It is natural to get rid of them.

Is this not a little like the All Highest? If she had been him, she would have said, quite sincerely: “Woe to all that dare to draw the sword against me. God is undoubtedly with me.”

But, of course, I wasn’t thinking of any Kaisers when I wrote the play. I wrote it before the war.

I wrote it in a wood near here (Dunsany Castle) toward the end of April in 1913.

But it’s curious what a fitting consort she would have made for the Inca of Perusalem.

She is sincere when she prays to the Nile. And I think that “The” Kaiser was sincere when he spoke of God, and gave orders for things to be done in Belgium that Ackazarpses’ mistress would never have sunk to.

As for teaching people, I only wish for them what I wish for myself, that they might escape from all the dull facts and equally dull lies that they are daily being taught by journalists, politicians, owners of encyclopaedias, and manufacturers of ugly things. While they still have power to be disgusted by the modern advertisement, let them come and see my plays; they shall trace the sources of my inspirations and rejoice with me in the pleasant rhythm of words; when knavery and ugliness seem natural, it is too late.

Lord Dunsany to E. H. Bierstadt Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry, Ireland.

April 9th, 1917 Dear Mr. Bierstadt:

My name will probably sound faintly familiar to you, but such big things have been happening in America on or about April 8th that I expect my name there now to evoke the comment that it evokes in England (except in the London Library where they haven’t heard of me at all), which is “Didn’t he write something some time or something of that sort?” Only that in your case you’ll be saying, “Didn’t I write something?” In any case the great Dunsany boom is about due to be followed by the great Dunsany slump.

Well, I think “The Gods of the Mountain” should survive it, and if “The Glittering Gate” doesn’t, so much the better. “Argimenes” is an imperfect play, but Stuart Walker seems to like it for its good points in spite of its faults. To place my plays in order of merit when some have not been acted is difficult, particularly when some are fresher in one’s mind than others, but I think that this is the order in which they will come:

1. Alexander 2. The Laughter of the Gods 3. The Gods of the Mountain and after that I don’t know, for I would always give preference to any play about the country of my spirit over some comedy whose scene was London or even a Yorkshire Inn. But I have a 3-act comedy called “The Ginger Cat” which I have hopes of. They were going to act it in London, but the war knocked all that.

The books that you kindly sent us have arrived today, and I have begun to make a few notes as you asked me. I am very much obliged to you for the interest you have taken in my work, all the more so because — whatever America, Russia, or Posterity may say — I am an unknown writer. Not that I have not always known where to find enthusiasm, and given generously with both hands, but given by few. Yet, after all, what do numbers matter?

I have lately found time in spite of soldiering to write in the afternoons, chiefly between four and six. I have been writing on March 29th and 30th, and on April 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th. With more leisure I should have done it in fewer days, but I have done two one-act plays, both comedies, one short, the other long. There are 3 characters in one, and 6 in the other, and of these 9 characters 8 are mortal, so that you see I am rather getting away from my usual themes.

Now I will end, though I have much to say, and will make notes in your book as you ask me, and one day will send it on its slow way back to America.

If the characters in my books could write to me as this character in your book is writing to you — what queer letters I should get.

Yours very sincerely, Dunsany.

Lord Dunsany to E. H. Bierstadt

Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry.

July 23rd, 1917.

Dear Mr. Bierstadt:

I was very glad indeed to hear from you. Such letters as I get from America are my only links with civilization. We have not the leisure here to attend to the affairs of civilization. It is quite right that we should not. The recumbent figure of Civilization must first of all be defended: afterwards, when barbarism has been driven away from her, we shall have leisure to attempt to restore her to animation.

I am rather hopeful of the future; for those who have seen war have seen one of the real and mighty things, and this should be such a touchstone all their lives by which to test the false and the trivial that managers and publishers may not find it so easy in the future to make money by false pretences. It is even possible that had I never been under shell fire I should have been unable to conceive anything of the size of the climax in “The Gods of the Mountain.”

“As a writer of plays we think that Lord Dunsany is not seen at his best. His dialogues are rather tedious, his plots are thin, and his dramatic situations are wanting in grip. Neither they (‘The Laughter of the Gods’ and ‘The Queen’s Enemies’) nor the two plays that follow them (‘The Tents of the Arabs’ and ‘A Night at an Inn’) are distinguished by any outstanding qualities. The frequent repetition of words and phrases in the first three plays reminds one of Maeterlinck — there is a great deal of palaver and very little result... with really good acting ‘A Night at an Inn’ might be interesting.” The Outlook — London.

“It is a literary pleasure to read these trifles.”

The Belfast News Letter.

That is the kind of reviews I get in this country, not because they dislike my work at all, but because of the inviolate English custom that no poet shall be welcomed until he is dead.

I am sorry to say that I am not fit to go to the front just yet as I have had five attacks of tonsillitis since I was in Belgium, but I have had that put right now and should be quite fit again inside a month.

To come to America and meet you, and many other friends is a day dream with which I often cheer my mind. Indeed my longing to go there was no doubt a large ingredient of the mood out of which I wrote “The Old King’s Tale”, a play which Stuart Walker has. My wife, who is a very good judge, likes this play best of all my plays except “Alexander”, though I put it fourth, about level with “The King of the Golden Isles”, after “The Gods of the Mountain,” with “The Laughter of the Gods” second.

When I have come to America, and after I have seen and talked with you all, and after I have seen and rejoiced in the hospitality that your theaters have extended to my dreams, then I want to do what may seem odd in a playwright. I want to get away into some of your mountains or big woods and go after bears or any other large game, for I prefer this even to the Theater. I have rather a nice collection of heads that I have shot in different countries, and which I hope to show you some day, for ships go both ways across the Atlantic. Of course I should have to find out before going after heads where was the right place to go, for there are right places and wrong places for that sort of thing all over the world, and there are guides who are anxious to show you one, and guides who are as ready to show you the other. I remember one of the wrong guides once in one of the wrong places who was going to show me a wolf: we went out at night and lay near a dead donkey, my guide pointed to the exact spot on the sky-line just before us by which the wolf would come: “Wolf he come down like a mountain.” he said. When after two or three failures he wanted me to come again, and I asked him if he could guarantee a wolf, he reproached me by summing up the uncertainties of this sport with the words, “Wolf he come from God”: an unjust reproach, since only a few nights earlier he had sworn in a cheerfuller mood, “Wolf he come, hyena he come, lion he come, everything he come.” But that was a long time ago, and I have learned better to discriminate guides since then.

I am aware of the irony of making plans for the future in these days, but I make them none the less. I am sorry a censor spoiled the seal on my last letter, but I suppose it can’t be helped.

The insect under your microscope, Dunsany.