I was not born where I should have been, in my father’s house, but in my grandfather’s.

When she heard the distant whistle of the early-morning freight train, Mazo gazed down the long, terraced hill toward the railway tracks below and assumed her racer’s crouch.

There was the train! Almost even with the edge of the lawn where she waited, the locomotive shrieked its challenge. Mazo shrieked hers. They were off!

Her long auburn hair flying, Mazo raced the train to the opposite end of the lawn.

She won! As always! And today the painted symbol on the boxcar just behind the locomotive was a full moon!

“A fine day, Grandma!” shouted Mazo as she ran toward the back door of the solid, two-storey, red-brick house. “It was a full moon, so it’s going to be a fine day.”

Inside the house a short, bright-eyed woman with wavy grey hair pulled back into a neat bun was already busy baking, despite the early hour. She smiled warmly as her cherished only grandchild entered the kitchen.

“My, you’re a big help,” said Grandma Lundy. “And you’re just five years old, the same age as my little sister Martha was when we moved to Cherry Creek. Martha didn’t have to help Mother. But I did. Of course I was a big girl of nine. I had no time to play. I had chores to do.”

“Chores are too much work,” commented Mazo, dancing around the room.

“That’s just how I felt!” exclaimed Grandma Lundy. “Why, I had to help my mother in the kitchen and the garden. I fed the chickens too. And I minded little Martha and baby Mary. We were pioneering in the primeval forest. My father and big brothers, Wellington and Lambert, were chopping down trees to make fields. There was so much to do, everyone had to help.”

“I don’t like helping,” said Mazo.

“You may say that now,” said Grandma Lundy. “But I could not. I had to help.”

“Tell me about how there was Willsons’ Hill and Clements’ Hill in Cherry Creek,” said Mazo. “Tell me how your little sister Martha married James Clement whose father was so rich.”

“You go and play, Mazo,” said Grandma Lundy. “I have work to do. I must bake four loaves of bread and two rhubarb pies.”

“There’s no one to play with,” said Mazo. “Father is in Toronto, Mother is sick in bed, Aunt Eva is dusting the sitting room so it will look nice when her gentleman-caller comes, Uncle Frank is working with Grandpa at the factory, Uncle George is working at the post office, Uncle Walter is at school, and Chub is outside barking at something.”

“Your father will visit in a few days, and he will take you back with him to Toronto,” said Grandma Lundy.

“I want somebody to play with now,” said Mazo.

“Since it is going to be a fine day, you and Grandpa and I will go for a drive in the buggy this afternoon. We must go and see my brother Wellington. He and his family don’t know their neighbours very well yet because they just moved from Cherry Creek last year, so Grandpa’s going to help with some carpentry work and I’m going to bring some baking.”

“Can we stop and see Grandpa’s Grandpa’s house?” asked Mazo.

“We can if you’re good,” said Grandma Lundy. “Now go read your storybook.”

Mazo de la Roche was born on January 15, 1879 in the village of Newmarket, York County, Ontario, in the home of her mother’s parents, Daniel and Louise Lundy. She was named Mazo Louise Roche. Her father, William Richmond Roche, gave Mazo her unusual first name. “Mazo” was supposedly the name of a girl Will Roche had once known and liked.

A few weeks after Mazo was born, Daniel Ambrose Lundy borrowed money to buy a house on Prospect Street in Newmarket. Most of Mazo’s first nine years of life were spent in this house, which still stands today. The house looked down at the Northern Railway tracks and across at the Main Street of Newmarket, population two thousand.

But Mazo spent summer vacations in the old Cherry Creek district at the south end of Innisfil Township, Simcoe County, about twenty kilometres north of Newmarket. Innisfil Township was where some of her Grandma Lundy’s nearest relatives lived, and where there was a nice lake to swim in: Lake Simcoe. Sometimes Mazo also visited her father’s family in Newmarket or, between 1884 and 1889, in Toronto.

Daniel and Louise Lundy were like parents for Mazo because her real parents, William and Alberta Roche, did not have their own home. Besides, Alberta was ill and could not run a household or raise a child. Alberta, or “Bertie,” was a pretty woman with gingery light-brown hair and violet eyes, and she loved pretty clothes. Bertie had been healthy when she married the dark-haired, dark-eyed Will Roche, who was tall and handsome, and who danced and talked charmingly. But Bertie caught scarlet fever when she was about to give birth to her first and only child, Mazo, and the ravages of the disease left her an invalid for decades.

Daniel and Louise (Willson) Lundy were the grandchildren of Quaker immigrants from the United States. These immigrants had come to Canada between about 1800 and 1810 and had cleared farms from the forest near Newmarket. Later, about 1840, Louise Lundy’s immediate family, the Willsons, had moved to Cherry Creek. When they grew up, Daniel and Louise Lundy became Methodists, as did many Quakers of their time and place.

Grandpa Lundy was a skilled worker and a natural leader. He was foreman of the William Cane woodenware factory in Newmarket. He designed and supervised the creation of the machinery used in the factory, and he also supervised the building of Newmarket’s town hall.

Mazo loved her Grandpa Lundy. He had thick silvery hair and blue eyes, and he was tall and strong. He was fun. He was kind and generous with his family and friends, and although he often got angry, he never got angry with Mazo.

The Lundy home was already crowded when newborn Mazo joined it. There were Grandpa and Grandma Lundy, of course, plus four adult children and one six-year-old boy. Sometimes too Mazo’s father came and stayed with the Lundys.

Although Mazo lived with a confusing crowd of close relatives, she was often lonely because none of these relatives were her own age. She sought companionship in stories, and she could be very affected by what she heard or read.

Once, when Mazo was very young, a much older child who lived nearby told her a ghost story about a woman with a golden arm. According to the story, the woman died and her husband sold her arm. But the woman haunted her husband, and moaned, “Bring me back my golden arm! Bring me back my golden arm!”

That night, Mazo lay awake in her bed with her hands over her ears and listened to the dead woman moan, “Bring me back my golden arm!” The ghost came closer and closer, past the stuffed owl on the stairs, closer and closer… Mazo jumped out of bed and fled down the stairs to the lit-up sitting room where the adults sat playing cards cheerfully. Soon she was safe in her father’s arms, and Grandpa Lundy was raging against the older child.

Mazo created her own little imagined world. Her playmates were made-up characters. And from the very beginning she was sensitive to words. As a baby, she had refused to talk baby talk. She always spoke clearly. Later, she often invented words such as beckittybock for petticoat, gillygaws for socks, and conehat for jacket.

At an early age she began to read. Soon she was devouring books voraciously, reading the Kate Greenaway books, Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Water Babies, and The Little Duke. She also read old issues of magazines for boys, like The Boys’ Own and Chum, that she found in the attic of the Lundy home.

The well-fed, muscular horse trotted smartly along the narrow dirt road flanked by massive oak trees. The sun shone, the birds sang, and the new green leaves rustled. Mazo, wedged comfortably between Grandpa and Grandma Lundy on the driver’s seat of the buggy, was thoroughly enjoying this excursion in the country on a fine spring day.

Finally Mazo spotted the stately, two-story, redbrick house on a hill. Mazo loved this house. This was Grandpa’s Grandpa’s house. Grandpa Lundy slowed the horse.

“Grandpa, were you born in your Grandpa’s house like I was born in your house?” asked Mazo, gazing at the handsome house, the big wooden barn, the blossoming orchard, and the moist, dark fields.

“I was born on the neighbouring farm where my brother Shadrack Lundy lives now,” said Grandpa Lundy. “When I was born, my Grandpa Lundy was still building the red-brick house. He finished it the next year. When I was your age, I spent many hours in this house, visiting my grandparents and playing with my cousins. It was a dark day last year when Cousin Silas Lundy sold our grandfather’s farm out of the family.”

“Did your grandfather have a thousand acres of land, Grandpa?” asked Mazo.

“Oh no, that was my great-great-great grandfather, Richard Lundy,” said Grandpa Lundy. “My grandfather, Enos Lundy Senior, owned only four hundred acres. And my father, Enos Lundy Junior, owned only one hundred acres. Richard Lundy received his land from the great William Penn himself. One thousand acres of primeval forest in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.”

“Did Richard Lundy come from the States up the Walnut Trail in a wagon?” asked Mazo.

“That was Enos Lundy Senior,” said Grandpa Lundy. “Richard Lundy came over the sea from England in a big sailing ship and founded our proud Lundy family in America. Why, the cow path where the Battle of Lundy’s Lane took place was named after my Grandpa Lundy’s first cousin, William Lundy, who owned a farm nearby. That was in the War of 1812.”

“Having a cow path named after you is nothing to be proud of,” sniffed Grandma Lundy.

“Another of Grandpa’s first cousins, Benjamin Lundy, was a pioneer abolitionist who wrote about the need to free the black slaves of America,” said Grandpa Lundy.

“I thought the Lundys were knights in the olden days,” said Mazo.

“That’s the Bostwicks,” said Grandpa Lundy. “My mother was a Bostwick. The Bostwicks were United Empire Loyalists in Nova Scotia, and knights back in old England. Now my mother’s mother – my Grandma Bostwick – was a Lardner. Grandma’s uncle, Nathaniel Lardner, was a famous biblical scholar in England. Her son, Lardner Bostwick, was one of Toronto’s first aldermen – he sat on the council with William Lyon Mackenzie. I remember when Grandma Bostwick got word that Uncle Lardner had died of the cholera plague in Toronto in 1834. She took the news awful hard. You see, Grandma Bostwick lived in Grandpa Lundy’s red-brick house too, because Uncle Isaac Lundy had married Aunt Keziah Bostwick…”

“Families are awfully confusing, Grandpa,” said Mazo, swinging her legs.

Mazo’s father, William Roche, worked for his brother, Danford Roche. By 1884, Danford Roche had stores in Barrie, Newmarket, Aurora, and Toronto. At the age of five, Mazo began to go by train occasionally to visit her father and his family in Toronto.

Toronto streets were not quiet like country roads. Horses, horses, everywhere! A team of powerful draft horses pulled a dray. A skinny horse pulled a butcher’s cart. Elegant horses pulled an elegant carriage. People everywhere! Women in their long flounced skirts. Men who looked like gentlemen. An Italian boy pushed his barrow of bananas and called, “Ban-ana ripe, fifteen cents a dozen!” The bananas were red.

The inside of Grandmother Roche’s house in downtown Toronto was dim and forbidding. Mazo held her father’s hand as they climbed the long, thickly carpeted stairway to Grandmother Roche’s mother’s room. Great-grandmother Bryan was ninety-two years old. She was dying! She was lying in the middle of a vast, four-poster bed.

“My little darling!” the old woman exclaimed in a surprisingly strong voice with a thick Irish accent. She reached out her long arms for Mazo. Great-grandmother Bryan was still charming, demonstrative, and domineering – an irresistible force!

Great-grandmother Bryan was Mazo’s father’s grandmother, and he loved his grandmother more than he loved his mother.

Will Roche lifted Mazo up so she could kiss Great-grandmother Bryan.

When the old woman hugged her closely, Mazo was afraid. She was grateful when her father rescued her. She clasped his neck tightly as he carried her down the stairs.

Around the table at dinner that day were red-haired and hot-tempered Uncle Danford; prim and proper Aunty Ida; calm and peace-loving Grandmother Roche; and black-haired and studious Uncle Francis. Mazo sat beside her father, and watched and listened.

“What was Father really like, Mother?” asked Uncle Francis. “Dan and Will were old enough to know him. But I…”

“Your father was not a common sort of man,” said Grandmother Roche. Mazo was impressed by the dignity of Grandmother Roche’s appearance. Her long waist was encased in a black bodice with white ruching at the neck and wrists. Around her neck was a long gold chain. Great-grandmother Bryan had given her that chain for being a good daughter.

“Mr. John Roche may have been descended from the aristocratic de la Roche clan of old France, but he was a rotter,” said Uncle Danford, who was standing at the head of the table carving a huge roast of beef. Aunty Ida was serving the potatoes, vegetables, and gravy.

“Your father left us to find a teaching position that suited him,” said Grandmother Roche.

“I know that, Mother, but what was he like? I mean his personality,” persisted Francis.

“I tell you he was a rotter,” insisted Danford, putting a generous slice of roast beef on his mother’s plate. “He never earned enough income to support a family. Mother had to work as a milliner. He deserted his wife and sons. Grandmother Bryan forbade Mother to follow him. But unfortunately Mother visited him once and conceived you. Fortunately Grandfather Bryan left us some property when he died, so we weren’t completely destitute. “

“Now Danny, your father was a brilliant scholar,” said Grandmother Roche. “You should be proud of him.”

“Oh yes, he was always planning reading courses for us, and sending us presents of books in French, Latin, and Greek,” said Mazo’s father. “And he corrected our grammar.”

“It was a mild spring morning and beginning to rain,” said Grandmother Roche, ignoring her full plate of steaming food. “I had just bought myself a new bonnet, trimmed with flowers and a satin bow. Little sister Fanny, who was then eight, was carrying the bonnet box. We came out of the milliner’s and were confronted by the shower. What were we to do? Return to the shop, when our mother expected us home? Never – we must face the rain.

“Just then a young man appeared before us – not only appeared but offered us the shelter of his umbrella! He bowed as he offered it. He spoke very correctly. And his looks! Why they fairly took my breath away! He was six feet tall, and stalwart. He was smooth shaven – that was unusual in those days. As for his clothes – never had I seen such elegance. His top hat was worn at just the right angle. His coat was dark blue with silver buttons. His cravat – I have no words fine enough to describe his cravat.”

“Eat up, Mother,” muttered Uncle Danford. “Your dinner will be cold.”

In 1826, Great-grandmother Bryan had emigrated from Ireland to Canada with her husband and children. Eventually the Bryans had settled in Whitby, where Great-grandfather Bryan worked as a shoemaker. The five Bryan boys mostly became tinsmiths or businessmen, although one, Jacob, became Whitby’s chief of police. The oldest of the three Bryan girls, Sarah, married John Roche. John Richmond Roche, M.A., was a fellow immigrant from Ireland and a teacher.

The Bryans hated John Roche. They were Methodists; he was Catholic. They were down-to-earth; he was high-faluting. They stuck together; he was a loner. Sarah’s marriage to John Roche did not last long. John Roche went to the United States by himself. Eventually he became a professor of mathematics at Newton University in Baltimore, Maryland.

In 1876, easy-going Will Roche, middle son of John and Sarah Roche, had come from Whitby, fifty kilometres east of Toronto, to Newmarket, fifty kilometres north, in order to help his older brother Danford. Danford Roche had just bought his first store. The store was on Main Street in Newmarket. His establishment, a general and dry-goods store, was called “The Leading House.”

Will soon married Bertie Lundy. Danford married Ida Pearson. Danford and Ida Roche never had children. Mazo was the only grandchild on her father’s side of the family too.

In 1880, despite his hatred of his father, Danford Roche had gone during hot July weather to fetch the body of Grandfather Roche from Baltimore to Newmarket for burial. At the age of sixty-six Grandfather Roche had dropped dead of sunstroke on the street in front of his boarding house. Uncle Danford had also fetched home twenty-eight boxes of Grandfather Roches expensive books. Uncle Danford had put the boxes in his stable in Newmarket. He had no room for them in his house. The books were great classics of literature. For a long time only Uncle Francis read the books. Much later Mazo read some of them too.

In 1884, Danford Roche bought a store on Yonge Street in Toronto, and his mother bought a house on John Street in Toronto. Now Will Roche was helping in the Toronto store, working variously as a clerk, manager, and cloth cutter. Danford had located his Toronto store next door to a similar establishment owned by Timothy Eaton. Danford was very competitive!

Mazo adored her father, and she found Grandfather Roche fascinating. Still, she was glad when the time came to go to Toronto’s Union Station and board the train back to Newmarket. Soon Mazo was allowed to ride the train herself. Off she went, in the conductor’s care, back to Grandpa and Grandma Lundy. She was not nervous, for the train was her friend.

The next morning, Mazo and the train raced again in the wind. Today on the first freight car there was a crescent moon. Mazo ran back to the house, into the room where Grandma Lundy was sewing.

“Bad weather, Grandma,” Mazo announced. “Thunderstorms!”

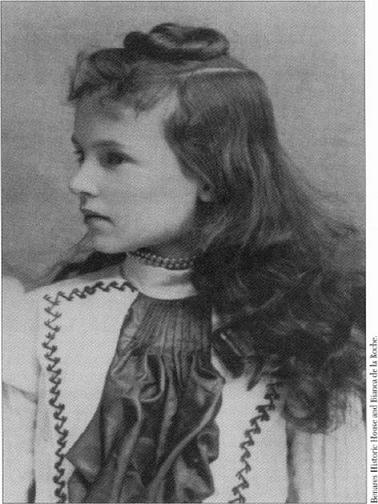

Maze de la Roche at eleven years