“This is Caroline,” my grandmother said to me. “You two little girls must be friends.”

When Caroline saw that Winnipeg was behind them and the long train was clacking faster and faster past flat, snow-covered prairie and bare aspen trees, she sighed, sat down, and began swinging her short legs back and forth restlessly.

The view out the window was boring again, like the view from Grand Forks to Winnipeg. Caroline hadn’t seen a single buffalo in the whole Dakota Territory. The Red River had been frozen and grey. The Pembina Mountains had been stupid hills.

“When will there be the forests and lakes in Ontario?” Caroline asked her mother.

“Tomorrow,” said her mother, pulling their lunch out of a bundle.

“Will Father be alone at Christmas?” asked Caroline, frowning.

“Serves him right if he is,” said her mother. “Now you eat your bread and cheese.”

Caroline ignored her sandwich and looked around the inside of the passenger car. It was early December 1886 and the car was crowded with Canadian families going Back East for the winter. Some were eating a cold meal. Others were playing cards. Still others were making beds for the little children who needed a nap… The seats were made of wooden slats. Above the seats were shelves that pulled down so they hung by rods and hinges.

Am I going to sleep on a shelf? Caroline asked herself. No! Never! I am eight years old!

At one end of the car were the washrooms. At the other end was a room with a stove to cook on. There was water at that end too. Everybody had to share. Caroline did not like sharing.

“How long will we be on this train?” asked Caroline.

“Two or three days,” said her mother.

“Why does the trip take so long?”

“Because we’re going almost as far as Toronto. We’ll get off the train in Cherry Creek, and Uncle Lambert will meet us. I wrote him a letter and told him we were coming.”

“Did you tell him I can recite, The Jackdaw of Rheims’?”

“Yes. And I said you could read well and sew beautifully.”

“I was born in Uncle Lambert’s house, wasn’t I?”

“Yes. Uncle Lambert’s house is near Aunt Mary’s house in Cherry Creek. Lambert is my older brother, and Mary is my younger sister. Cherry Creek is where your father and I grew up. In Cherry Creek there was Willsons’ Hill and Clements’ Hill…”

“Did it take three days for us to go Out West and join Father in Grand Forks?”

“Oh no! It took much longer than that! About one week. The Canadian Pacific Railroad was just finished this year. Seven years ago we had to go through the United States to reach Grand Forks. We took the train from Lefroy to Toronto, Toronto to Sarnia, Sarnia to Chicago, Chicago to St. Paul, St. Paul to Grand Forks.”

“Are we going to borrow money from our relatives Back East?”

“Certainly not! And don’t you mention one single thing about our problems to one single soul!”

“I won’t,” said Caroline. She bit into her sandwich angrily.

Mazo supposed her eighth birthday, on January 15, would be as gloomy as Christmas and New Year’s Day had been. Grandpa and Grandma Lundy were still terribly sad about Uncle Frank. Everyone was. Mazo’s mother said everyone should stay in Newmarket until after January 14, so Grandpa and Grandma wouldn’t have to face the first anniversary of Uncle Frank’s tragic death alone.

Uncle Frank’s head had been cut off by a saw! “No blame whatever can be attached to anyone for the sad occurrence,” the newspaper had said. “It was purely accidental.” The terrible tragedy had happened on the day before Mazo’s seventh birthday!

Uncle Frank’s death was why Mazo’s father and her Uncle George Lundy had not gone back to Toronto yet. Instead they had gone somewhere in the horse-drawn sleigh through the snow on an errand, and they had come back with a big bundle.

Uncle George sat down in Grandpa Lundy’s armchair and began to remove layer after layer of shawls from the bundle on his lap. The adults stood about, waiting and watching. None of them took any notice of Mazo, who hung back. From the top of the bundle hung strands of silvery fair hair like the limp petals of a flower. There was a child in the bundle! A girl!

The girl stared about her. She looked dazed. Her hair hung down to her shoulders, but it was cut squarely into a straight thick fringe above her blue eyes. She had high cheekbones, a square little chin and full curling lips. She looked as though she would never, ever smile again.

Mazo’s mother and Aunt Eva asked the girl all sorts of questions about where she had been and what she had seen.

The girl answered every question with only two words: “Yes, ma’am” or “No, ma’am.”

“Listen to her!” exclaimed Aunt Eva. “Why, she’s a real little American!”

“I think you and Caroline had better go off and get acquainted, Mazo,” said Grandma Lundy. “Tea will be ready soon. Caroline must be starving.”

Uncle George set the girl on her feet. She came and put her hand into Mazo’s.

Mazo led Caroline into the red-carpeted sitting room and showed her where the Christmas tree had stood touching the ceiling. Then Mazo started up the stairs to show Caroline her favourite book, Through the Looking Glass. Halfway up the stairs, Mazo and Caroline stopped where the stuffed white owl sat in a recess in the wall.

“He’s pretty,” said Caroline. She let go of Mazo’s hand, stood on tiptoe, and put both her hands underneath its wings.

“He was alive once,” said Mazo, who was afraid of the owl. “He flew around in the woods and killed things. He was wicked. At night he comes down and flies all over the house and hoots. I’ve heard him.”

“Ah ha ha ha!” laughed Caroline merrily, and she scampered up the stairs.

Mazo, astonished that Caroline was not afraid, ran after her.

Chub, the fox terrier, barked and came running too.

As far as young Mazo was concerned, Caroline Clement came into her life like a white rabbit pops out of a black top hat: by magic. One day Caroline simply appeared. Presto! There she was! Mazo’s father and uncle had brought the girl from some relatives who didn’t like children. But in fact Caroline’s arrival at the Lundy house in Newmarket was the result of many years of money problems due to the restless seeking of Caroline’s father: James Clement.

For Caroline’s mother, Martha (Willson) Clement, the family finances had been a worry in the West as well as the East. When Martha had married James Clement in the early 1850s, he had owned a forty-hectare farm in Cherry Creek just a kilometre or two from the Willsons. James Clement had got his farm for 150 dollars from his wealthy father, Lewis James Clement, who owned more than 400 hectares of land in Innisfil Township. James wanted to raise show horses and show them in New York State.

But James had sold this farm and bought another farm nearby that was not cleared and had no house. James and Martha had lived over the store across the road from the farm, and James had managed the store. Then James had sold his second farm to pay some debts. After that, James and Martha and their first two children had lived in hotels in Bell Ewart and Bracebridge while James had managed the hotels. Then, in the summer of 1877, James had left Martha and the children with Grandmother Willson in Innisfil Township and travelled to the American West to scout new opportunities. After James was gone, Martha realized she was pregnant.

The baby, Caroline Louise, was born April 4, 1878. One year later, Martha, eight-year-old Mary Elizabeth, five-year-old James Harvey, and baby Caroline joined James in the Dakota Territory. In booming Grand Forks, James found plenty of work as a carpenter, and in 1882 he managed to purchase a sixty-five-hectare property on the edge of town by borrowing six hundred dollars: a large sum of money at that time. The family seemed settled at last.

But in 1883 – the same year that Mary Elizabeth died – James borrowed another large sum of money to capitalize on an invention he had patented: a ditch-digging machine. Unfortunately, this business scheme failed. In the summer of 1885, the sheriff seized James’s property and auctioned it to the highest bidder in front of the court house in Grand Forks. Now Martha, James, and their surviving children were living in a rented house, and James wasn’t able to pay the rent.

In December 1886, Martha Clement and two children boarded a Winnipeg-bound train in Grand Forks. Martha needed to see her family. Back in Cherry Creek, after the hot Christmas dinners had been digested and the warmly remembered relatives had been visited, the chill reality of Martha Clement’s difficult position set in. Where was the penniless woman to spend the winter? Where were her children to stay?

The many brothers and sisters of Martha and James Clement had their own families to support. Their houses were mostly full. They had their own problems to deal with…

Thankfully, Martha’s sister, Louise (Willson) Lundy, who lived just a short train-ride away in Newmarket, felt that the two little female cousins, Caroline and Mazo, just nine months apart, would get along fine and be less trouble than one. They did and they were.

When Martha Clement boarded a westbound CPR train and went back to Grand Forks that spring, she took her son but left Caroline behind. During the next three years, Caroline flourished under the loving care of her Aunt Louise.

The two little girls came together like two drops of water. It was just as though they had always been together, they were so completely companionable, so completely seemed to fill each others needs. Most of the time they lived in an imagined world of Mazo’s making.

Mazo had created this world when she did not have a child her own age to play with, and now she shared it with Caroline. Caroline couldn’t create, but she could follow. She was wonderful at following the creator, and at imagining! She could imagine herself anything at all, and that of course helped Mazo’s imagination greatly. Any situation that Mazo imagined, Caroline was in it, heart and soul.

As time went on, Mazo and Caroline introduced more and more characters into their imagined world. They added old people, middle-aged people, babies, upper-class people, lower-class people, priests, schoolboys, engineers, maids, actresses, horses, and dogs. More than a hundred characters! As Mazo and Caroline got to know the characters better, they ceased to act them. They were them. When surrounded by other people, they strained toward the moment when they could be alone together. Then, at once, the real world became unreal. The vivid reality was their play.

The girls carried their imagined world with them when they moved in 1888 with the Lundys to Orillia, a small town in Simcoe County, about one hundred kilometres north of Newmarket. Daniel Lundy could not bear to continue working in the factory where his son, Frank, had been killed, so he accepted a position as foreman of the Thompson brothers’ woodenware factory in Orillia. Today Orillians call it the Old Pail Factory.

In Orillia, Mazo and Caroline were the youngest in a household that included Mazo’s mother, Bertie, as well as Aunt Eva, Uncle Walter, and Grandpa and Grandma Lundy. Will Roche still joined the Lundy household occasionally, and Bertie and Mazo joined Will occasionally in his rented rooms in Toronto.

Will was no longer working for his older brother. Danford Roche’s Toronto store had failed, and his mercantile empire had collapsed. Uncle Danford had retreated to Newmarket and gone into business with a relative of his wife. Grandmother Roche had sold her house in Toronto to redeem Danford’s credit, and she too had retreated to Newmarket. Will now worked at a variety of jobs. For example, he was both a traveller for a wholesale grocer and the treasurer of a civic spectacle in Toronto called, “The Cyclorama of the Battle of Sedan.”

In the summers, the family made one-day excursions by ferry from Orillia to tiny Strawberry Island in Lake Simcoe, where Mazo and Caroline imagined they were Robinson Crusoe and Friday in a cave. The family also went on longer excursions to Cherry Creek, where they stayed in a little cottage by Lake Simcoe. In those days there were no cars or speedboats, The summer cottages were few and they were surrounded by farmlands. One summer, Mazo’s mother, Caroline, and Mazo all had matching, blue-flannel bathing dresses trimmed with white braid.

During the rest of the year, Mazo and Caroline studied in a little private school run by Miss Cecile Lafferty, later Mrs. Gerhardt Dryer, wife of Orillia’s chief of police. The school was located on Coldwater Road, not far from where the Lundys lived. Outside of school the girls enjoyed recreational reading like Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. In the fall and spring they took long walks and played the usual childhood games, like hide-and-seek. In the winter they skated. Mittened hands held mittened hands as a dozen children did a crack-the-whip across the rink. Mazo’s and Caroline’s skates never fit right, and their flannel petticoats always got in the way.

Now and then Mazo and Caroline tried acting as well as imagining. The two girls, in costume, would act out plays for their family. As well, the girls tried writing a newspaper that contained stories, verses, riddles, and news. They printed the newspaper by hand and sold it to the family for two cents a copy. Perhaps the price was too high, for the newspaper did not last long.

Mazo, seated at the kitchen table, wrote on and on. While Grandma Lundy kneaded the bread dough and made an apple pie, Mazo covered eight whole, foolscap pages!

“What are you writing, Mazo?” asked Grandma Lundy.

“A story,” Mazo replied without looking up. She kept on writing.

“Youth’s Companion is advertising a short-story competition for children of sixteen and under,” said Mazo’s mother, entering the kitchen with Caroline. “Mazo thinks she can win.”

“Its a story about a lost child named Nancy,” said Caroline.

“But Mazo is only ten,” said Grandma. “She can’t compete with sixteen-year-olds.”

“There! It’s finished,” announced Mazo, putting down her pen and gathering up the pages. “Nancy went through terrible times. She was forced to eat potato peels. But at last she was restored to her mother. And her mother quoted St. Luke, Grandma. When Nancy came home, her mother said: ‘It was meet that we should make merry, and be glad: thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.’”

“But darling,” said Mazo’s mother, “do you think a child would ever be so hungry she would eat potato peels?”

“Nancy was,” Mazo said firmly.

“And do you think her mother would quote a Bible text the moment her child was given back to her?” asked Mazo’s mother. “It sounds so pompous!”

This criticism Mazo could not answer. She stared down at the pages in her hands.

“I’m dead sure I’d eat potato peels if I were hungry enough,” came the voice of Mazo’s father from behind her. “And as for the text – it was the proper thing for the mother to quote. Don’t change a word of your story, Mazo. It will probably win the prize.”

Two weeks later, Mazo received a long envelope in the mail. Inside was her story. It had not won the competition. Also inside was a letter from the editor of Youth’s Companion. It said: “If the promise shown by this story is fulfilled, you will make a good writer yet.”

“Isn’t that splendid!” exclaimed Mazo’s mother.

Mazo sat on a stool in a corner, covered her face with her hands, and sobbed out her disappointment. Her family, not knowing what to say, stood around her for a long time.

Finally her father spoke.

“Come on, Mazo,” he said. “I’m going to teach you how to play cribbage. It’s a good game, and you have no idea how comforting a game of cards can be.”

In 1889, Caroline’s parents and older brother arrived in Orillia. The reunion was not happy because Caroline’s father was not happy. James Clement was a poor man who could barely afford to rent a few small rooms to shelter his family. He and his teenage son were working at menial jobs in the pail factory where his brother-in-law, Daniel Lundy, was the foreman. Daniel Lundy – Mazo’s Grandpa Lundy – had given the jobs to James and his son.

James still owned about twenty hectares of land in Cherry Creek that had been willed him by his father. But he could not make a living from this land, and he could not sell it. Grandfather Clement’s will stated that the land must go to James’s children after James died. Anyway, James didn’t want to live near his family in Cherry Creek. His family scorned him.

All of his brothers and sisters had done better than he had! Stephen was sheriff of the entire western judicial district of Manitoba. Sarah and her husband had a farm in Manitoba. Lewis was a medical doctor in Bradford, Ontario. Catherine’s husband had been a successful merchant in Barrie, Ontario; furthermore, he had represented the riding of North Simcoe in the Parliament in Ottawa for nine years. Even Joseph, David, and Eliza, who never left Cherry Creek, at least owned forty or more hectares of land there. What was wrong with James?

James was a traitor! He had forsaken queen and country! He had become an American citizen! Although the Clements were of French, Dutch, and German descent, they had been officers in the British army for four generations. They had been United Empire Loyalists, pioneers of Niagara, heroes of the War of 1812. They had fought against the Americans. James’s grandfather had been killed in that war! James was the black sheep! He had no pride!

Officially, Caroline Clement, now eleven, was living again with her parents and brother. But James, Martha, and James Junior were strangers to her, so she often rejoined Mazo at the Lundys. There Caroline could forget about her unhappy father and the cold Clements.

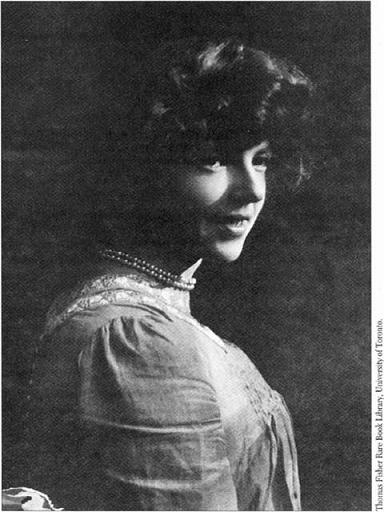

Mazo de la Rache at about eighteen.